Water is a fundamental resource for life and food security. However, many regions of the world, including Morocco, are facing increasing water scarcity due to their semi-arid climate and excessive consumption, particularly in the agricultural sector, which is the primary consumer of water resources, accounting for nearly 70% (Hssaisoune et al. 2020). In this context, soil hydraulic conductivity (Ks) is crucial in water availability and management, as it determines how easily water infiltrates and moves through the soil. Soils with low hydraulic conductivity limit water infiltration, leading to excessive surface runoff, inefficient irrigation and reduced groundwater recharge. Conversely, soils with high hydraulic conductivity allow better water absorption and aquifer recharge, promoting more sustainable water use and reducing irrigation needs (Arrington et al. 2013). Drought in general influences water shortage in the soil, plants or in the atmosphere (Takác 2013). In semi-arid regions, such as Morocco, where climate change is exacerbating water scarcity through erratic rainfall and rising temperatures, optimising water management is essential to ensure the longterm sustainability of agriculture. Several national initiatives, such as the ‘Green Morocco Plan’ and ‘the National Water Program’, have been implemented to promote water conservation and improve agricultural practices (Bekkaoui et al. 2024). However, continued pressure on natural resources requires ongoing efforts to build resilience to climate change.

The spatial variability of soil properties significantly impacts water distribution in agricultural fields. Hydraulic conductivity is a key parameter in hydrological modelling, controlling soil–water interactions, nutrient transport and contaminant movement (Gao et al. 2018). However, measuring soil hydraulic properties in the field or the laboratory is often expensive and time-consuming, requiring specialised equipment and expertise (Castellini et al. 2021). Given the high spatial variability of soil hydraulic properties, obtaining accurate estimates requires extensive sampling. In fact, a broad sampling procedure is essential to determine the spatial variability of soil properties for an adequate assessment of soil conditions and appropriate recommendations (Alekseev, Abakumov 2020). Researchers have explored alternative methods to overcome this challenge, including predictive models based on easily measurable soil properties and geostatistical techniques that estimate values at unsampled locations (Mohanty et al. 1994, Moosavi, Sepaskhah 2012).

Traditional hydrological models often assume uniform soil hydraulic properties over large areas, typically 100 km2 to 10,000 km2. However, such assumptions can lead to significant errors in estimating surface runoff, infiltration and other hydrological processes due to the natural spatial variability in soil properties (Braud 2003). Studies of saturated hydraulic conductivity have shown considerable spatial heterogeneity; for example, Mallants et al. (1997) found that only 50% of the measured Ks values showed spatial dependence, with a semi-variogram range of 14 m. Similarly, Rogers et al. (1991) reported high spatial variability in the hydraulic properties of saturated clay soils in Louisiana, USA, with limited spatial correlation. Ghorbani et al. (2011) investigated Ks variability in the Tangnesarbon district, Iran, and found a semi-variogram range of 3720 m and a nugget-to-total semi-variance ratio of 56%. Alemi et al. (1988) analysed 315 sites in Azerbaijan and Iran and found spatial dependence at a distance of 3 km. In addition, Sobieraj et al. (2004) highlighted the role of spatial and temporal variations in soil nutrient and water availability, which are shaped by complex interactions between soil properties, topography and agricultural practices (Mohanty et al. 2000). The crucial role of soil hydraulic conductivity in water management and agricultural productivity highlights the importance of studying it, as it provides valuable insights for optimising irrigation strategies (Huang et al. 2019). Furthermore, understanding Ks in spatial variability can help develop precision irrigation techniques, improve groundwater recharge and enhance agricultural sustainability in water-scarce environments.

Thus, adequate characterisation of Ks is crucial for optimising irrigation, improving groundwater recharge and improving water management strategies (Kifanyi et al. 2019). Despite its importance, accurate assessment of the spatial distribution of Ks remains a challenge due to its high variability across different soil types. While previous research has explored the spatial distribution of various soil properties using interpolation and geostatistical methods, it has explicitly focussed on saturated hydraulic conductivity at large scales in irrigated perimeters using spatial interpolation methods (Gumiere et al. 2014). Most existing studies address soil variability at more minor spatial scales, which limits their applicability to regional hydrological modelling and irrigation planning. This knowledge gap hampers efforts to develop accurate soil–water interactions and groundwater recharge models in semi-arid agricultural areas (Ibrahim et al. 2024).

In the Tadla Plain, previous studies have focussed on analysing soil quality and the spatial distribution of soil parameters (Barakat et al. 2017, El Hamzaoui et al. 2020, 2021, Hilali et al. 2020, Mouaddine et al. 2025). However, no studies have been conducted regarding determining the spatial variability of soil Ks. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to determine the spatial variability of soil Ks in the Beni Moussa irrigated perimeter, the Tadla Plain, Morocco. This study presents one of the first comprehensive assessments of Ks in the Beni Moussa irrigation perimeter, a key agricultural region in Morocco. Integrating in situ measurements with geostatistical techniques bridges the gap between localised soil property analyses and broader hydrological applications. This research will provide added value by offering accurate data on the Ks distribution, essential for improving irrigation management and optimising water use while contributing to implementing sustainable water resource management strategies in the study area.

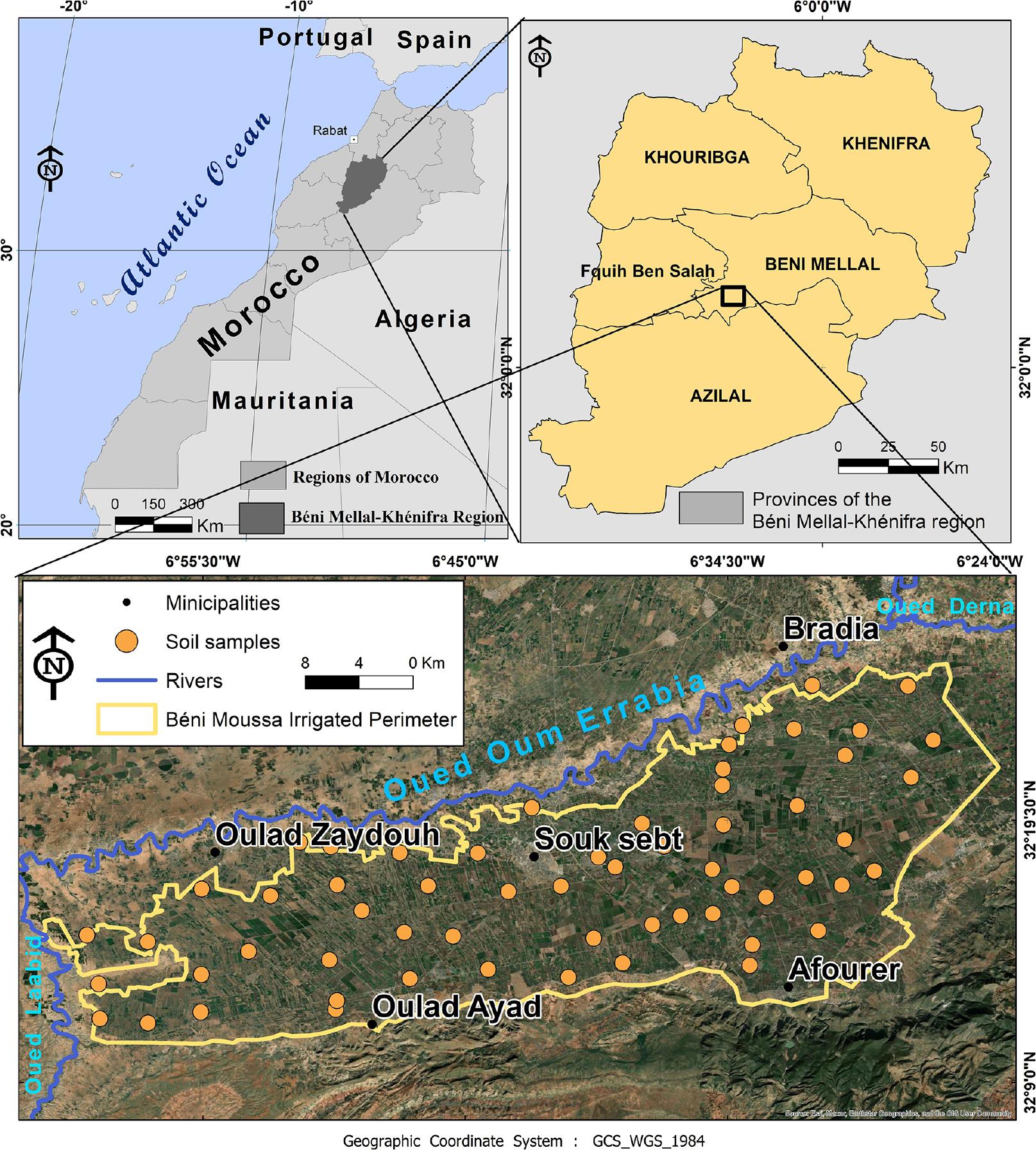

This study was conducted in central Morocco, within the irrigated perimeters of Beni Moussa, part of the agricultural zones, Tadla plain, supported by the Oum Er-Rbia River. Although the two perimeters are distinct, they share similar climatic and hydrological characteristics (Barakat et al. 2017). The Beni Moussa perimeter covers an area of approximately 69 500 ha, while the Beni Amir perimeter covers an area of 33 000 ha, both of which play a crucial role in regional agricultural production (El Baghdadi 2022).

The study area is characterised by a semi-arid climate, with an average annual temperature of 19°C and annual rainfall of around 280 mm (El Hammoumi et al. 2013). Due to the limited and erratic rainfall, irrigation from the Oum Er-Rbia River is essential for sustaining agricultural activities. The soils in the region exhibit considerable variability in texture and structure, which affects water infiltration, retention and overall soil hydraulic properties. Given these conditions, optimising water use and improving irrigation efficiency remain critical challenges for sustainable agricultural development in the region.

Seventy soil samples were collected from the Beni Moussa region of the Tadla Plain between 2020 and 2022 at a depth of 0–20 cm. Sampling points were georeferenced using a Global Positioning System (GPS) device. Before laboratory analysis, collected samples were air-dried, homogenised, and sieved through a 2 mm mesh. All analyses were performed in triplicate to ensure accuracy. Figure 1 shows the location map of the study area, showing the soil sampling points.

Location map of the study area showing soil sampling points.

pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were determined using a Hanna Instruments HI5521-02 and multi-parameter pH metre. Soil pH was measured in 1:2.5 (w/v) soil/water slurry, while EC was analysed in a 1:5 (w/v) soil/water suspension after equilibration. A multiparameter conductivity metre quantified total dissolved solids (TDS) from soil extracts.

Soil organic matter (OM) plays a crucial role in the growth, development and productivity of cultivated plants (Becher et al. 2020). OM and organic carbon (OC) were determined by the loss-on-ignition (LOI) method at 550°C in a muffle furnace. OM content was calculated as the weight loss after ignition, and OC was estimated by applying a conversion factor:

Calcium carbonate (CaCO3) was quantified by the calcination method at 950°C in a muffle furnace. The weight loss between 550°C and 950°C was attributed to the decomposition of carbonates. The CaCO3 content was calculated from the mass difference before and after heating.

Soil texture was analysed using the international Robinson pipette method (NF X 31-107, 2003). OM was removed with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and carbonates were dissolved with hydrochloric acid (HCl) before dispersion with sodium hexametaphosphate. Fine fractions (clay and silt) were separated according to Stokes’ law. It is important to note that these methods are standardised according to AFNOR (1996) and (Saidi et al. 2008)

The saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ks) was measured in situ using the simple ring infiltrometer and Porchet methods. This technique consists of inserting two concentric metal rings into the soil, filling them with water and monitoring infiltration over time to calculate Ks from steady-state infiltration rates (Porchet, Laferrere 1935). Dry bulk density (BD) was determined using the core method, where soil samples were oven-dried at 105°C for 24 h to obtain bulk density (Klute, Page 1986). Water content (WC) variation (△θ) was measured by gravimetric analysis by determining soil moisture loss after drying at 105°C.

The statistical analysis of soil parameters was conducted using various methods to investigate their relationships. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the data distribution, including mean, standard deviation (SD) and range. Pearson correlation analysis assessed the strength and direction of relationships between different soil properties. Additionally, principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to identify the main factors influencing soil hydraulic and physicochemical properties (Mishra et al. 2019). All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics.

Ordinary kriging (OK) was used to estimate values at unmeasured locations, ensuring unbiased predictions with minimal variance. The estimated value is calculated using Eq. (1): where:

- –

z(xi) represents measured values,

- –

λi is the kriging weights,

- –

N is the number of samples.

The weights were determined by solving equations that ensure unbiasedness and minimal error variance ‘OK’ was selected as it provided the best fit between measured and estimated values based on the semi-variogram model parameters (Biswas, Si 2013).

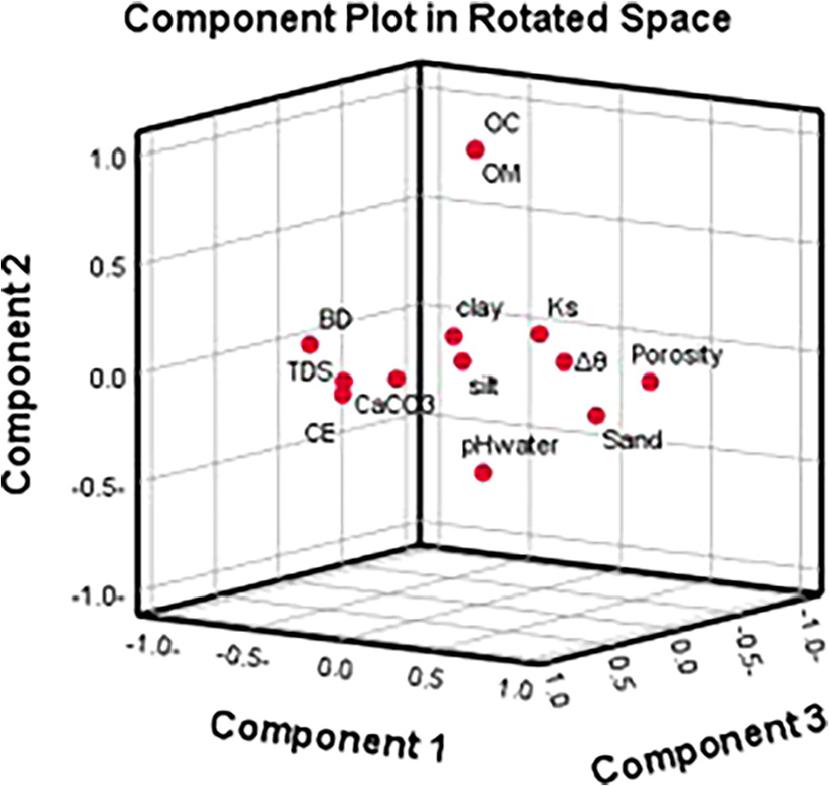

PCA was conducted on the normalised dataset to compare the variables between the soil samples and all parameters influencing each one. PCA evidences three factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, which explain about 70.73% of the total variance (Fig. 2).

PCA of the physicochemical soil parameters of Beni Moussa irrigated perimeter. PCA, principal component analysis.

Table 1 summarises the descriptive statistics for the different studied soil characteristics. The mean saturated hydraulic conductivity of the soils (Ks) was 380.68 mm · h−1 and ranged from 32.60 mm · h−1 up to 679.06 mm · h−1. The average sand, silt and clay contents, as well as their sampling ranges (in %), were 2.25, 13 and 7, respectively. The clay content was always lower than silt and higher than sand at all sampling points. The OM content in the studied soil is as follows: the soil’s reaction was generally alkaline, with the mean, minimum and maximum pH (in H2O) values of 7.06, 7.84 and 8.64, respectively. The mean EC was 24.3 μS · cm−1 and ranged from 289.65 μS cm−1 to 1414 μS · cm−1. The average, minimum and maximum values of bulk density (BD), total porosity and WC (△θ) were 0.82 g · cm−1, 1.17 g · cm−1 and 1.43 g · cm−1; 45.00%, 54.6% and 68.53% and 0.74%, 18.88% and 49.39%, respectively. Skewness describes the degree of asymmetry of a distribution around the mean. For most variables, the skewness was moderate (<1). However, it was slightly more positive (<2) for soil EC, TDS, OM and carbonate content (CaCO3). Kurtosis values show a notable variability between variables. Some, such as EC (3.568), dissolved solids (3.826) and OM (5.996), show marked leptokurtosis, reflecting high concentrations around the mean and frequent extreme values. In contrast, pH (-0.926) and clay (-0.440) show platykurtosis, indicating a flatter distribution with fewer extreme values. Most of the other variables have near-zero kurtosis, indicating relatively normal distributions.

Descriptive statistics for soil properties at 0–20 cm depth in the study area.

| Soil parameter | Descriptive statistics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit | N | Mean | Max | Min | SD | Variance | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

| Saturated hydraulic conductivity | mm · h−1 | 70 | 380.68 | 679.06 | 32.60 | 147.61 | 21,791.200 | 0.852 | –0.112 |

| Bulk density | g · cm−1 | 70 | 0.82 | 1.43 | 1.17 | 0.13 | 0.019 | –0.437 | 0.219 |

| Porosity | (%) | 70 | 45.00 | 68.53 | 54.60 | 5.26 | 27.699 | 0.437 | 0.219 |

| Water content | (%) | 70 | 0.74 | 49.39 | 18.88 | 7.96 | 63.393 | 0.844 | 2.695 |

| Water | –log[H+] | 70 | 7.06 | 8.64 | 7.84 | 0.41 | 0.171 | –0.123 | –0.926 |

| Electrical conductivity | μS · cm−1 | 70 | 24.30 | 1414.00 | 289.65 | 293.78 | 86,309.040 | 1.884 | 3.568 |

| Total dissolved solids | mg · l−1 | 70 | 11.87 | 750.00 | 171.75 | 168.34 | 28,339.940 | 1.908 | 3.826 |

| Organic matter | (%) | 70 | 2.53 | 27.98 | 9.72 | 4.12 | 17.047 | 1.869 | 5.996 |

| CaCo3 | (%) | 70 | 1.50 | 16.20 | 5.63 | 2.39 | 5.736 | 1.869 | 5.996 |

| Clay | (%) | 70 | 7.00 | 61.30 | 38.89 | 14.09 | 198.600 | –0.775 | –0.440 |

| Silt | (%) | 70 | 13.00 | 81.26 | 41.47 | 15.03 | 226.135 | 0.662 | 0.266 |

| Sand | (%) | 70 | 2.25 | 34.85 | 17.25 | 6.11 | 37.406 | 0.670 | 0.883 |

SD – standard deviation.

Table 2 presents the Pearson correlation coefficients between various soil parameters, highlighting key interactions among soil properties. A strong negative correlation is observed between clay and silt (–0.906**), indicating that clay-rich soils tend to have lower silt content. Similarly, silt shows a moderate negative correlation with sand (–0.355**), suggesting that higher silt proportions are generally associated with lower sand content, influencing soil structure and permeability.Additionally, OM negatively correlates with pH (–0.429**), implying that higher organic content is linked to more acidic soils. Guo et al. (2024) argued that increased soil alkalinity can enhance nutrient availability, thereby improving the water retention capacity of plants. WC (△θ) exhibits a positive correlation with both sand (0.249*) and pH (0.314**), suggesting their role in soil moisture dynamics. In contrast, porosity is inversely related to bulk density (–1.000***), indicating that higher porosity corresponds to lower bulk density and vice versa (Alongo, Kombele 2009). Finally, Ks shows a positive correlation with WC (0.333**) and silt (0.264*), emphasising the importance of these factors in soil infiltration (Klute 1973, García-Gutiérrez et al. 2018).

Pearson correlation analysis of soil variables in the study area.

| Soil parameter | Correlations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay | Silt | Sand | Organic carbon | pH H2O | Water content | Porosity | Bulk density | Saturated hydraulic conductivity | |

| Clay | 1 | ||||||||

| Silt | –0.906** | 1 | |||||||

| Sand | –0.022 | –0.355** | 1 | ||||||

| Organic carbon | 0.168 | –0.064 | –0.179 | 1 | |||||

| pH H2O | –0.045 | –0.018 | 0.087 | –0.429** | 1 | ||||

| Water content | –0.124 | 0.040 | 0.249* | –0.225 | 0.314** | 1 | |||

| Porosity | –0.089 | –0.118 | 0.455** | 0.015 | –0.079 | 0.224 | 1 | ||

| Bulk density | 0.089 | 0.118 | –0.455** | –0.015 | 0.079 | –0.224 | –1.000** | 1 | |

| Saturated hydraulic conductivity | –0.295* | 0.264* | 0.068 | –0.040 | 0.069 | 0.333** | –0.117 | 0.117 | 1 |

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (bilateral);

correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (bilateral).

PCA of the physicochemical properties of the studied soil, obtained using Varimax rotation, is presented in Figure 2. The results indicate that the correlation between OM and OC is because OM serves as the primary source of OC in soils, influencing its dynamics and bioavailability (Lal 2004). The relationship between clay, silt and saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ks) is associated with soil structure, as higher clay content decreases soil permeability by enhancing water retention and particle cohesion (Dexter 2004). Additionally, bulk density (BD), TDS and EC are closely linked, as an increase in bulk density reduces soil porosity, which in turn affects water availability and the concentration of soluble ions (Corwin, Lesch 2005). These findings are consistent with the results obtained from Pearson correlation analysis, further validating the observed interactions among soil properties.

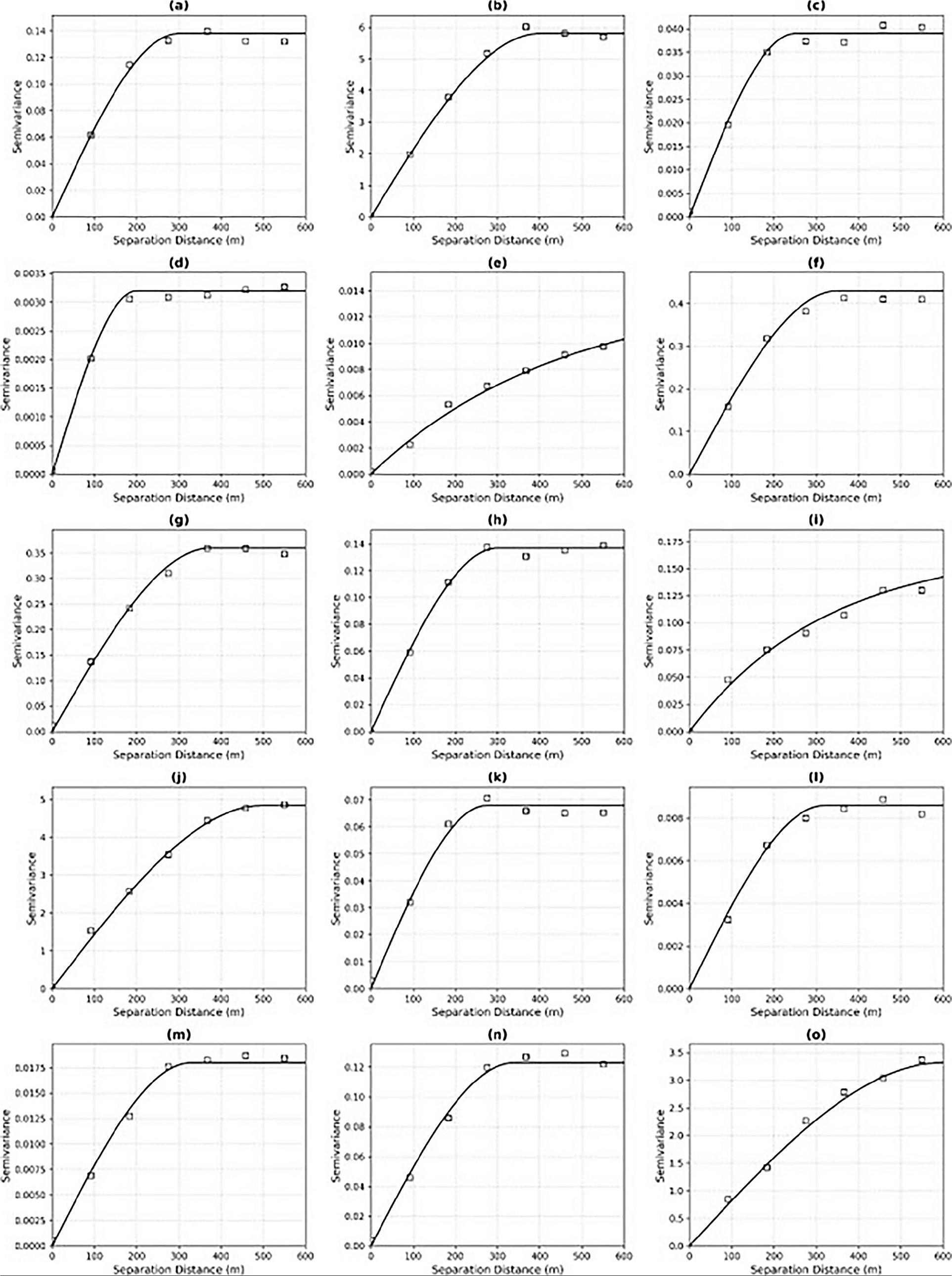

Table 3 variogram parameters and Moran’s I statistics show distinct spatial patterns for every soil property. The predominance of spherical models (13/14 instances) suggests that the variables have defined spatial relations with specified range parameters. Interestingly, most of the properties are moderate-to-strong in spatial structure, as supported by N/S ratios <50% for 8/14 parameters (e.g., Ks: 28.7%; porosity: 41.6%), meaning that the variables are favourable for geostatistical interpolation. However, some of the properties (pH-water, clay, and TDS) have high N/S ratios (>70%), indicating high microscale variability or measurement error may be dominating their spatial patterns. The range parameters are extremely variable (5739–39,549 m), representing property-specific correlation lengths governed by underlying paedogenic processes. Moran’s I values also confirm these trends, with positive autocorrelation (I > 0) for pH-KCl (0.219), BD (0.296) and Ks (0.201) contrasting with negative autocorrelation (I < 0) in EC (-0.168) and △θ (-0.220). The exponential △θ model (N/S = 30.6%) suggests heterogeneous spatial dynamics in comparison to other properties, which could be an expression of more progressive spatial decorrelation. These results collectively show that while most soil properties possess strong spatial structure, their interoperability varies depending on their distinctive geostatistical signature.

Best suited variogram models and Moran’s I.

| Soil parameter | Semi-variogram model | Nugget C0 | Sill (C0 + C) | N/S [%] | Range [m] | Moran’s I |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH (water) | Spherical | 0.0196 | 98.67 | 77.47 | 23,943.08 | 0.097 |

| Electrical conductivity | Spherical | 0.0015 | 32.25 | 20.27 | 36,857.24 | –0.168 |

| CaCO3 | Spherical | 0.0164 | 125.99 | 71.28 | 38,431.47 | 0.188 |

| Organic carbon | Spherical | 0.0095 | 138.88 | 62.95 | 20,929.04 | –0.184 |

| Sand | Spherical | 0.0016 | 98.44 | 52.48 | 5738.90 | 0.070 |

| Clay | Spherical | 0.0183 | 68.80 | 86.05 | 37,250.14 | –0.002 |

| Silt | Spherical | 0.0038 | 22.60 | 48.89 | 5939.51 | –0.163 |

| Porosity | Spherical | 0.0192 | 168.97 | 41.56 | 10,851.70 | 0.231 |

| Saturated hydraulic conductivity | Spherical | 0.0042 | 114.51 | 28.70 | 5838.28 | 0.201 |

| Organic matter | Spherical | 0.0147 | 121.40 | 56.65 | 5215.99 | –0.162 |

| pH (KCl) | Spherical | 0.0031 | 92.53 | 53.84 | 20,617.10 | 0.219 |

| Total dissolved solids | Spherical | 0.0172 | 5.37 | 88.92 | 11,538.66 | –0.140 |

| Water content | Exponential | 0.0010 | 0.85 | 30.59 | 23,207.25 | –0.220 |

| Bulk density | Spherical | 0.0112 | 151.38 | 36.13 | 39,548.55 | 0.296 |

The performance of the fitted semi-variogram models presented in Table 3 was assessed using cross-validation based on four key metrics: mean error (ME), root mean square error (RMSE), root mean square standardised error (RMSSE) and average standard error (ASE). These indicators, summarised in Table 4, allow for evaluating the accuracy and stability of the interpolations performed through OK.

Cross-validation metrics for 14 soil parameters.

| Soil parameter | Mean error | Root mean square error RMSE | Root mean square standardised error RMSSE | Average standard error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH (water) | –8.98E–07 | 0.0086 | 0.8049 | 0.0107 |

| Electrical conductivity | –0.00026496 | 5.7996 | 0.7820 | 7.4201 |

| CaCO3 | –0.000938 | 0.0183 | 0.8570 | 0.0214 |

| Organic carbon | –0.000006 | 0.0399 | 0.7782 | 0.0511 |

| Sand | –0.000056 | 0.1373 | 0.8078 | 0.1702 |

| Clay | –0.000201 | 0.4317 | 0.8036 | 0.5378 |

| Silt | 0.000049 | 0.3668 | 0.3026 | 1.2130 |

| Porosity | 0.000015 | 0.1693 | 0.6288 | 0.2693 |

| Saturated hydraulic conductivity | 0.000110 | 4.8441 | 0.8058 | 6.0197 |

| Organic matter | –0.000103 | 0.0687 | 0.7782 | 0.0884 |

| pH (KCl) | –0.000705 | 0.0086 | 0.8049 | 0.0107 |

| Total dissolved solids | 0.000001 | 0.1381 | 0.8409 | 0.1649 |

| △θ | –0.000015 | 0.0141 | 0.7615 | 0.0186 |

| Bulk density | –1.68E–07 | 0.0032 | 0.8349 | 0.0039 |

The validation results show that most variables have RMSSE values close to 1, which indicates good model calibration. For instance, the saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ks), modelled using a spherical semi-variogram (RMSSE = 0.8058), demonstrates reliable interpolation performance, supported by a ME close to zero (ME = 0.000110) and a moderate RMSE (4.8441). Similarly, textural parameters, such as sand, clay and silt, all modelled using spherical semi-variograms, show RMSSE values ranging from 0.30 to 0.81, confirming their geostatistical relevance.

Some variables, such as soil WC (△θ) and porosity, modelled using exponential and spherical models, respectively, present RMSSE values slightly <1 (0.7615 and 0.6288), which suggests moderate underestimation, often due to greater spatial heterogeneity. This observation aligns with the relatively high nugget values observed in their semi-variograms, indicating a significant portion of unstructured or small-scale variability.

The data distribution is symmetrical for most parameters, with minimal skewness. However, parameters, such as EC and TDS, exhibit more significant variability, requiring model improvements. Despite this, most soil properties are well-modelled, though moisture and hydraulic conductivity variability warrant particular attention (Fig. 3).

Fitted semi-variogram for the selected soil property: A – CaCO3, B – electrical conductivity, C – organic carbon, D – bulk density, E – stability, F – clay, G – silt, H – sand, I – moisture using the exponential model, J – Saturated hydraulic conductivity, K – organic matter, L – pH water, M – pH_KCl, N – porosity, and O – total dissolved solids using the spherical model.

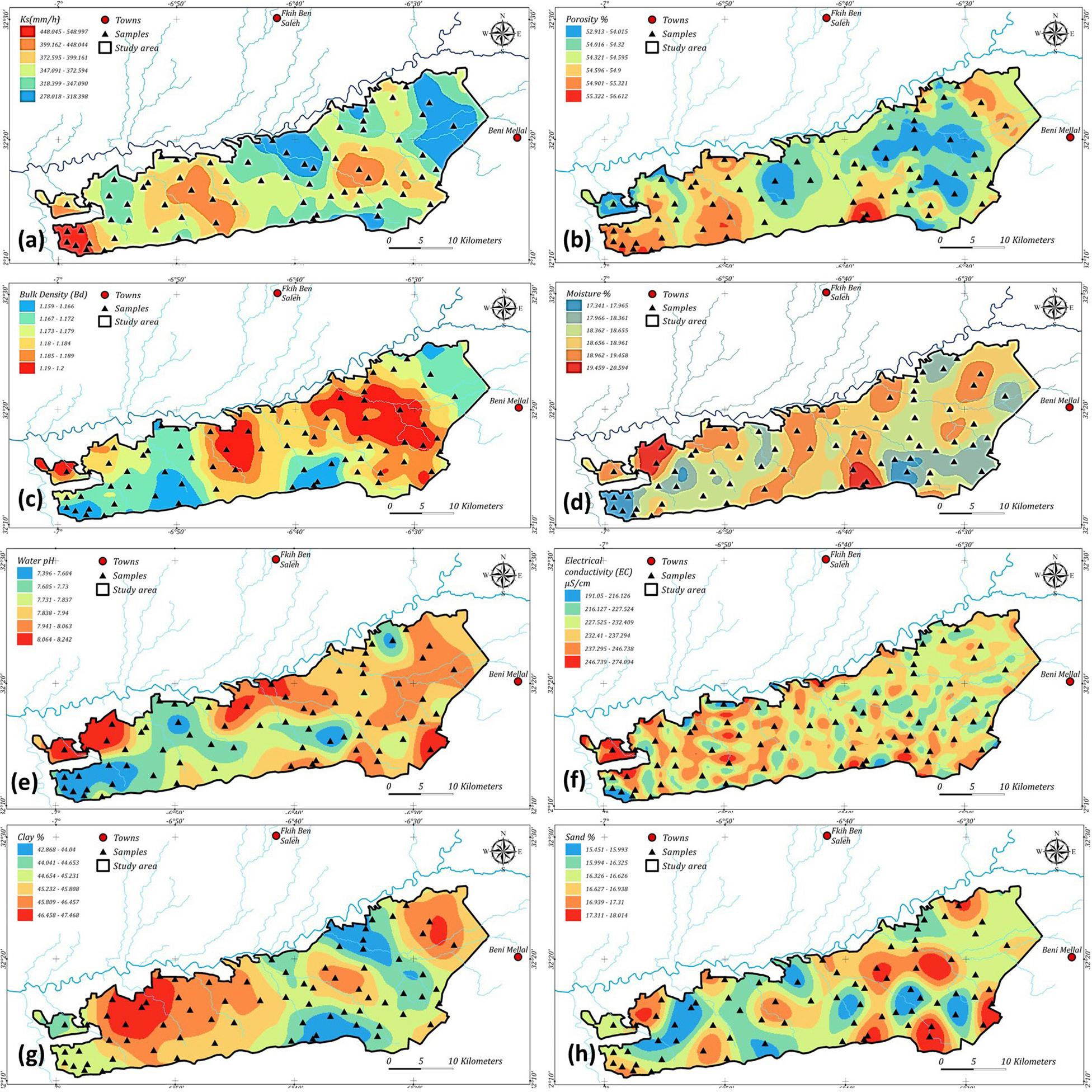

The kriging maps generated in this study (Fig. 4) allowed the identification of two sub-areas with distinct saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ks) values. The northern part of the study region exhibited higher Ks values (>3.0 m · day−1), while the southern part showed lower Ks values (<3.0 m · day−1). According to previous classifications, the northern area can be categorised as having high to very high Ks; whereas, the southern area falls into the reasonably high to low categories.

Kriging maps produced for Beni Moussa irrigated perimeter: (a) – saturated hydraulic conductivity Ks(mm · h−1); (b) – porosity%; (c) – bulk density; (d) – moisture%, (e) – pH water; (f) – electrical-conductivity (μs · cm−1); (g) – clay (%); (h) – sand (%).

A comparison of the maps in Figure 4 highlights a substantial positional similarity between areas with high Ks values and those with high sand content (>74%) and low silt content (<22%). This correlation can be attributed to the influence of the sand fraction on the abundance of large, connected pores, which enhance water movement through the soil. This effect is supported by findings from Lim et al. (2020), who observed that Ks values in coarse sand (5.98 m · day−1) decreased by 57%, 88% and 96% as sand content successively decreased in fine sand, loam and clay soils.

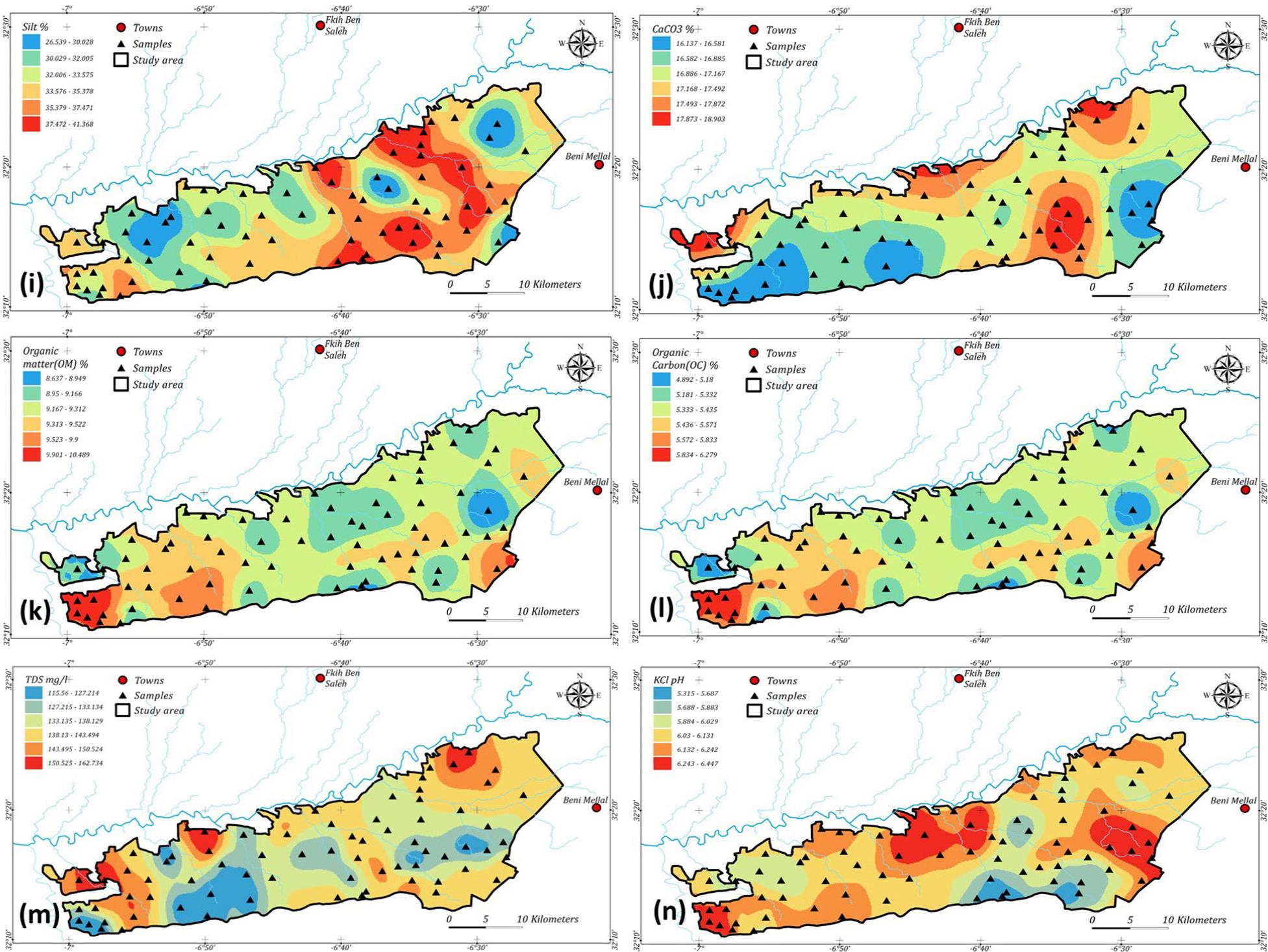

Kriging maps produced for Beni Moussa irrigated perimeter: (i) – silt (%); (j) – carbonate de calcium CaCO3 (%); (k) – organic matter (%); (l) – organic carbon. (m) – total dissolved solids and (n) – pHKcl.

Field observations and previous studies in the Beni Moussa region indicate that limited crop growth and lower yields tend to be associated with high sand content areas. This may be due to excessive drainage, which leads to insufficient water availability for crops under unsaturated conditions. Additionally, rapid water movement in sandy soils contributes to chemical leaching, reducing plant nutrient availability.

These results suggest that high Ks values indicate low-yielding areas, particularly in coarse-textured soils, where excessive permeability limits water and nutrient retention. Conversely, low Ks values in fine-textured soils may also signal low productivity zones, as slow infiltration can lead to waterlogging and oxygen deficiency, particularly in wet conditions. Keller et al. reported similar findings in loam and clay soils (Ks ranging from 0.6 m · day−1 to 25.2 m · day−1), where low-yielding zones corresponded to areas with lower Ks values due to blocky soil structures that restrict water movement.

These findings indicate that the impact of Ks on soil productivity is highly dependent on soil texture. In coarse-textured soils, high Ks can result in nutrient depletion and water loss, while in fine-textured soils, low Ks can lead to water stagnation and reduced oxygen availability for plant roots. Therefore, defining threshold Ks values specific to different soil textures is crucial for optimising soil productivity and irrigation strategies.

The kriging maps of Ks can be a valuable tool for local authorities and agronomy experts in spatial planning and site-specific soil management practices. In sandy soils, Ks can be reduced by adding organic amendments, such as biochar, composted manure, or spent mushroom, substrate to improve water retention. Strategies, such as reduced tillage, controlled traffic and OM incorporation in clayey soils, can enhance porosity and prevent excessive compaction.

Long-term solutions, such as crop rotation with deep-rooted species or even land conversion to grassland, could further contribute to soil stabilisation, carbon sequestration and improved water retention. These approaches should be considered for sustainable agricultural planning in semi-arid regions, such as Beni Moussa.

These results highlight the heterogeneity of soils in the study area regarding their physical and chemical properties, with direct implications for water infiltration, nutrient availability and soil fertility. The saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ks) exhibits significant spatial variability, with high values in the north, attributed to a high sand content and low silt content. This configuration promotes rapid infiltration but leads to excessive drainage and nutrient loss, limiting crop growth in these areas (Hillel 2003, Saxton, Rawls 2006). Conversely, areas rich in clay and silt exhibit lower Ks values, which can result in water stagnation and oxygen deficiency for plant roots (Dexter 2004).

Statistical analysis reveals significant correlations between different soil parameters. The negative correlation between clay and silt (–0.906**) indicates a well-defined textural dynamic influencing porosity and water retention (Weil et al. 2017). Similarly, hydraulic conductivity is positively correlated with silt (0.264*) and WC (0.333**), highlighting the importance of these factors in infiltration dynamics (Bouma 1989). Furthermore, OM is inversely correlated with pH (–0.429**), which aligns with observations that soil acidification can improve the availability of specific nutrients (Tan 2010).

Geostatistical analysis, based on kriging models, shows that sandy soils are prone to significant water and nutrient loss, compromising their fertility. In contrast, silty and clayey soils are more likely to experience excessive water retention and compaction issues (Webster, Oliver 2001). These findings confirm the necessity of differentiated soil management based on texture and hydraulic conductivity. In highly permeable areas, adding OM and crop diversification can enhance water and nutrient retention (Lal 2006). For more compact soils, reduced tillage and OM enrichment can improve porosity and limit water stagnation (Six et al. 2000).

Kriging maps for soil management provide a valuable tool for spatial planning and optimising agricultural practices. These maps help identify areas requiring specific interventions, such as targeted irrigation, adjustments in cultivation practices and rational fertiliser application (Goovaerts 1997). In the context of sustainable soil management in semi-arid environments, these approaches could contribute to strengthening the resilience of agricultural systems against climatic and environmental challenges (Lambin et al. 2003).

Finally, the distinction between this study and previous research (Oumenskou et al. 2019, El Hamzaoui et al. 2020, 2021, Ennaji et al. 2020, Hilali et al. 2021, Barakat et al. 2023, El Baghdadi 2022) can be justified by several key methodological aspects that have a major impact on the results. First, the spatial distribution of sampling points is critical, as soil properties exhibit considerable heterogeneity between sites. Variations in soil texture, moisture content and chemical composition can lead to different hydrological and agronomic behaviours, highlighting the need for independent sampling strategies to ensure a comprehensive assessment. Second, the temporal dimension of sampling plays an essential role in capturing soil dynamics. Environmental conditions, such as precipitation patterns, temperature variations and anthropogenic influences, evolve, resulting in seasonal and interannual variations that can significantly affect soil properties. These include hydraulic conductivity, OM decomposition and nutrient availability. By considering both spatial and temporal variability, this study provides a unique perspective that complements and extends previous findings, reinforcing the robustness and relevance of its methodological approach.

This study provided a comprehensive assessment of the spatial variability of saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ks) in the Beni Moussa irrigated perimeter, located in the Tadla plain at the foot of the central High Atlas, in a semi-arid climate in central Morocco, which faces increasing water scarcity and agricultural pressure. Using field measurements, laboratory analyses and geostatistical modelling (ordinary kriging), this study revealed strong spatial heterogeneity of Ks values, closely linked to soil texture, porosity and bulk density. Moreover, the results showed that sandy soils, predominant in the northern part of the study area, had high Ks values, favouring rapid water infiltration but also leading to excessive drainage and nutrient leaching. In contrast, clayey and silty soils in the southern zones exhibited low Ks values, increasing the risk of water stagnation and reduced oxygen availability for plant roots. These contrasting patterns highlight the need for site-specific soil management strategies tailored to local hydraulic conditions.

The use of ordinary kriging enabled the generation of reliable spatial maps, offering a valuable decision-support tool for precision irrigation planning and sustainable land use management. The integration of soil physical and chemical properties into predictive models strengthens the relevance of these maps for both agricultural and environmental applications. These findings have several important implications: (i) emphasising the importance of considering Ks variability when designing irrigation systems to avoid under- or over-irrigation; (ii) supporting the use of organic amendments and texture-specific soil management practices to improve water retention or mitigate waterlogging and (iii) highlighting the potential of geostatistical methods for characterising hydraulic properties at the study area context.

Future research should aim to: incorporate temporal dynamics of Ks to account for seasonal and interannual variability. Expand the spatial scale of analysis to include adjacent perimeters, such as Beni Amir for regional planning. Integrate remote sensing data and machine learning algorithms to enhance prediction accuracy. Evaluate the impacts of land use change and agricultural practices on soil hydraulic behaviour over time. By improving the understanding of Ks spatial patterns and their controlling factors, this study contributes to the development of more efficient irrigation strategies and soil conservation practices, supporting long-term agricultural sustainability in semi-arid environments.