The mental health of college students has gained increasing attention in recent years. They frequently encounter significant anxiety and depression, as confirmed by multiple studies (Aruta et al., 2022; Cao et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2020). The World Health Organization (2018) identified suicide and depression as the second and third leading causes of death among individuals of this age, with numerous studies reporting that some students consider dropping out or exhibit suicidal tendencies (Alejandria et al., 2023; Bangalan et al., 2023; Grasdalsmoen et al., 2020; Sivertsen et al., 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these challenges, disrupted traditional learning, and affected student well-being (Barrot et al., 2021; Waseem et al., 2020).

Mental health is recognized as a fundamental human right and a pillar of sustainable development (WHO, 2022). The United Nations reinforces this through Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3, which promotes good health and well-being, and SDG 4, which emphasizes inclusive and equitable quality education. Achieving these goals requires educational institutions to support both academic success and student mental well-being.

Despite these global commitments, there is limited research on how Filipino college students actually use mental health services. National and regional data show high rates of anxiety and depression among youth (Acob et al., 2021; Alibudbud, 2021; Billote et al., 2022), including 13.6% in the Zamboanga Peninsula who have considered suicide (UP Population Institute, 2023). Yet, university records indicate that while more than half of reported mental health concerns involve depression, actual service use remains low.

Attitudes toward mental health services are known to influence utilization, but positive perceptions do not always lead to help-seeking behavior (Kukoyi et al., 2022), suggesting that other barriers exist. Social support, a well-established protective factor, is often overlooked in mental health programs. Strong support systems—whether from family, peers, or even pets—can facilitate help-seeking, while social isolation often exacerbates mental health challenges (Acoba, 2024; Corrigan et al., 2014). However, few studies in the Philippine higher education context have examined social support as a predictive factor in service utilization.

By addressing both mental health outcomes and access to services, this study supports SDG 3 by identifying barriers to care and promoting student well-being. It also supports SDG 4 by highlighting the importance of emotionally supportive learning environments. The findings aim to inform evidence-based policies that strengthen integrated support systems and highlight the critical role of social networks in mental health care.

Moreover, this study adds to existing literature by integrating mental health status, attitudes, and social support as predictors of service utilization in a Philippine university context—an area previously underexplored. Ultimately, this study provides insights into how universities can foster enabling environments that promote both mental health and educational success, ensuring that no student is left behind in the pursuit of health and quality education.

This study aimed to examine the mental health status, attitudes toward mental health services, levels of social support, and actual utilization and its barriers to mental health services among college students at a university in Zamboanga City, Philippines. Additionally, it purports to see whether mental health status, attitudes, and social support are associated with service utilization.

This study utilized an institution-based descriptive cross-sectional design. The study population included 13,993 students enrolled during the first semester of the 2023–2024 academic year at a university in Zamboanga City, Philippines. This population comprised regular students, returnees, shifters, and transferees across eleven colleges and two external studies units of the university.

A stratified random sampling was employed based on shared characteristics such as gender and year level. From each stratum, students were randomly selected to form the final sample of 332, determined using a 5% margin of error, a 95% confidence level, and a 33% response distribution.

Data collection took place from July to November 2024 using a five-part questionnaire. Part 1 collected data on the socio-demographic characteristics and student-related information of the respondents. Parts 2 to 4 comprised of the following scales: Depression Anxiety Stress Scales - Short Form (DASS-21), Attitude Toward Mental Health Services Scale (ATMHSS), and Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS).

DASS-21 assessed the mental health status of respondents. The scale has seven items each for depression, anxiety, and stress. Each of the 21 items is rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. 0 – did not apply to me at all, 1 – applied to me to some degree or some of the time, 2 – applied to me to a considerable degree or a good part of the time, 3 – applied to me very much or most of the time (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). The item scores on each scale are totaled and multiplied by 2 to obtain the three scale scores, as shown in Table 1.

DASS-21 Severity Ratings

| Depression levels | Anxiety levels | Stress level | |

|---|---|---|---|

| normal | 0–9 | 0–7 | 0–14 |

| mild | 10–13 | 8–9 | 15–18 |

| moderate | 14–20 | 10–14 | 19–25 |

| severe | 21–27 | 15–19 | 26–33 |

| extremely severe | 28 and more | 20 and above | 34 and above |

DASS-21 is widely applicable and has been translated into 45 different languages. It was also widely investigated for its reliability and validity across different nations such as Australia, England, Canada, Malaysia, Brazil, China, Pakistan, Germany, USA, and UK. The scale has also been applied to diverse racial groups (Black, White, Latino, and Asian).

Studies had shown that the DASS-21 has good internal consistency reliability (Cronbach's alpha ranged between 0.74 and 0.93) in both clinical and non-clinical samples. It was tested for validilty and reliability to studies involving adolescents (Le et al., 2017; Naumova, 2022) and students (Wittayapun, 2023).

The ATMHSS examined the attitudes of the respondents toward mental health services provided in and outside of the university. It has 12 items, nine of which were adapted from the Inventory of Attitudes Toward Seeking Mental Health Services (IASMHS) (Mackenzie et al., 2004). The IASMHS scale has already been validated in Ireland, Russia, France, Austria, Portugal, and the Philippines (Tuliao et al., 2019). For this study, the twelve items covered the three factors of IASMHS: psychological openness, help-seeking propensity, and indifference to stigma. The scale ranges from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 4 (Strongly Agree).

The PSSS assessed the level of social support received by respondents in relation to their utilization of mental health services. The section comprised eight items adapted from the study of Kukoyi et al. (2022). Responses were measured using a 4-point Likert scale: Never (1), Rarely (2), Occasionally (3), and Always (4). The total scores were then categorized to reflect levels of social support: poor (8–18), moderate (19–25), and strong (26–32).

Part 5 focused on students' use of mental health services, evaluating mental health service utilization in and outside the university through single-choice questions.

The questionnaire for this study underwent expert validation. DASS-21 (0.91) had excellent internal consistency, and acceptable scores for attitude (0.71) and social support (0.73) scales. Descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, analysis of variance, Spearman correlation and logistic regression were used for analysis. The significance level was set at 0.05, and IBM SPSS software was used for processing.

The actual collection of data commenced after obtaining the ethics clearance from the Research Ethics Oversight Committee of Western Mindanao State University with reference number 2024-IF-0508 on June 28, 2024. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants and data were anonymized.

Table 2 shows that most students (58.43%) are aged 20–22, with a nearly equal gender distribution (49.4% male, 50.6% female). The majority are single (90.96%) and Roman Catholic (62.35%). Most students come from nuclear families (66.57%) and low-income households (63.85%). Year 1 students make up the largest group (26.2%), with fairly even representation across year levels 1 to 4.

Demographic profile of students

| Categories | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 164 | 49.4 |

| Female | 168 | 50.6 | |

| Age Group | 17–19 | 121 | 36.45 |

| 20–22 | 194 | 58.43 | |

| 23–26 | 17 | 5.12 | |

| Civil Status | Single | 302 | 90.96 |

| In a relationship | 30 | 9.04 | |

| Religion | Roman Catholic | 207 | 62.35 |

| Islam | 87 | 26.2 | |

| Protestant | 12 | 3.61 | |

| Others | 26 | 7.83 | |

| Ethnicity | Zamboangueño | 162 | 48.8 |

| Tausug | 73 | 21.99 | |

| Yakan | 5 | 1.51 | |

| Subanen | 8 | 2.41 | |

| Others | 84 | 25.3 | |

| Family Structure | Nuclear | 221 | 66.57 |

| Extended | 40 | 12.05 | |

| Single Parent | 52 | 15.66 | |

| Stepparent Family | 7 | 2.11 | |

| Grandparent Family | 8 | 2.41 | |

| Others | 4 | 1.2 | |

| Family Monthly Income | Less than ₱ 9,520 | 118 | 35.54 |

| Between ₱ 9,520 to 19,040 | 94 | 28.31 | |

| Between ₱ 19,040 to 38,080 | 62 | 18.67 | |

| Between ₱ 38,080 to 66,640 | 31 | 9.34 | |

| Between ₱ 66,640 to 114,240 | 16 | 4.82 | |

| Between ₱ 114,240 to 190,400 | 7 | 2.11 | |

| At least ₱ 190,400 | 4 | 1.2 | |

| Year Level | 1 | 87 | 26.2 |

| 2 | 83 | 25 | |

| 3 | 80 | 24.1 | |

| 4 | 76 | 22.89 | |

| 5 | 6 | 1.81 | |

| Total | 332 | 100 | |

Table 3 shows that the mental health status of college students predominantly reveals moderate levels of depression (36%), with moderate (29%) and extremely severe (29%) levels of anxiety, and normal levels of stress (47%). Overall, 86% of students experience mild to extremely severe depression, 80% exhibit moderate to extremely severe levels of anxiety, and 35% encounter moderate to extremely severe levels of stress. Only less than 15% of the students have normal levels of depression and anxiety.

Levels of Mental Health Status (DASS-21) of College Students.

| Levels | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. | Percent | Freq. | Percent | Freq. | Percent | |

| Normal | 47 | 14.16 | 40 | 12.05 | 156 | 46.99 |

| Mild | 69 | 20.78 | 27 | 8.13 | 60 | 18.07 |

| Moderate | 119 | 35.84 | 97 | 29.22 | 78 | 23.49 |

| Severe | 68 | 20.48 | 72 | 21.69 | 31 | 9.34 |

| Extremely Severe | 29 | 8.73 | 96 | 28.92 | 7 | 2.11 |

| Mean Score (SD=7) | 16.91 | 15.47 | 15.98 | |||

| Total | 332 | 100 | 332 | 100 | 332 | 100 |

DASS Scores Interpretation:

Depression = 0–9 Normal, 10–13 Mild, 14–20 Moderate, 21–27 Severe, 28+ Extremely Severe

Anxiety = 0–7 Normal, 8–9 Mild, 10–14 Moderate, 15–19 Severe, 20+ Extremely Severe

Stress = 0–14 Normal, 15–18 Mild, 19–25 Moderate, 26–33 Severe, 34+ Extremely Severe

Additionally, the data implies that the average scores for depression (16.91), anxiety (15.47), and stress (15.98) among the college students surveyed fall within the moderate range of DASS-21. The standard deviation (SD=7) suggests that while some students may have lower or higher levels of these mental health concerns, the majority experience moderate levels.

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics for the Attitude Toward Mental Health Services. The overall mean score is 32.14, indicating a generally positive attitude toward accessing mental health services.

Descriptive Statistics for Attitude Toward Utilization of Mental Health Services

| Total Score ATMHSS_12 | Help-Seeking Propensity | Indifference To Stigma | Psychological Openness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 32.14 | 10.70 | 14.47 | 6.95 |

| SD | 5.00 | 2.31 | 3.33 | 1.91 |

| Median | 32 | 11 | 15 | 7 |

| Total Items | 12 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| Maximum Total | 48 | 16 | 20 | 12 |

| Middle Point | 24 | 8 | 10 | 6 |

Help-seeking propensity. In the help-seeking propensity subscale, the mean score is 10.70 (SD=2.31) indicates a moderate to high willingness among students to seek professional help when needed.

Indifference to Stigma. The mean score of 14.47 suggests that students appear largely unconcerned about the social stigma associated with seeking mental health services. Although some variability in scores is observed (SD=3.33).

Psychological openness. This refers to the willingness to acknowledge and talk about mental health concerns. The mean score of 6.95 indicates a moderate level of openness. Notably, this subscale shows the least variability (SD=1.91), suggesting that respondents' views are relatively consistent.

Table 5 indicates that nearly half of the respondents (48%) reported receiving moderate support, while 42% indicated poor support. Only a small portion—about 10%—reported strong social support.

Levels of Social Support to Mental Health Services Utilization

| Levels of Social Support | Score Range | Freq. | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | 8–18 | 140 | 42.17 |

| Moderate | 19–25 | 158 | 47.59 |

| Strong | 26–32 | 34 | 10.24 |

The 42% reporting poor support highlights a substantial group potentially lacking the necessary encouragement or guidance from family, peers, or the community. In contrast, the relatively small proportion of students with strong support indicates that only a few receive consistent and meaningful encouragement.

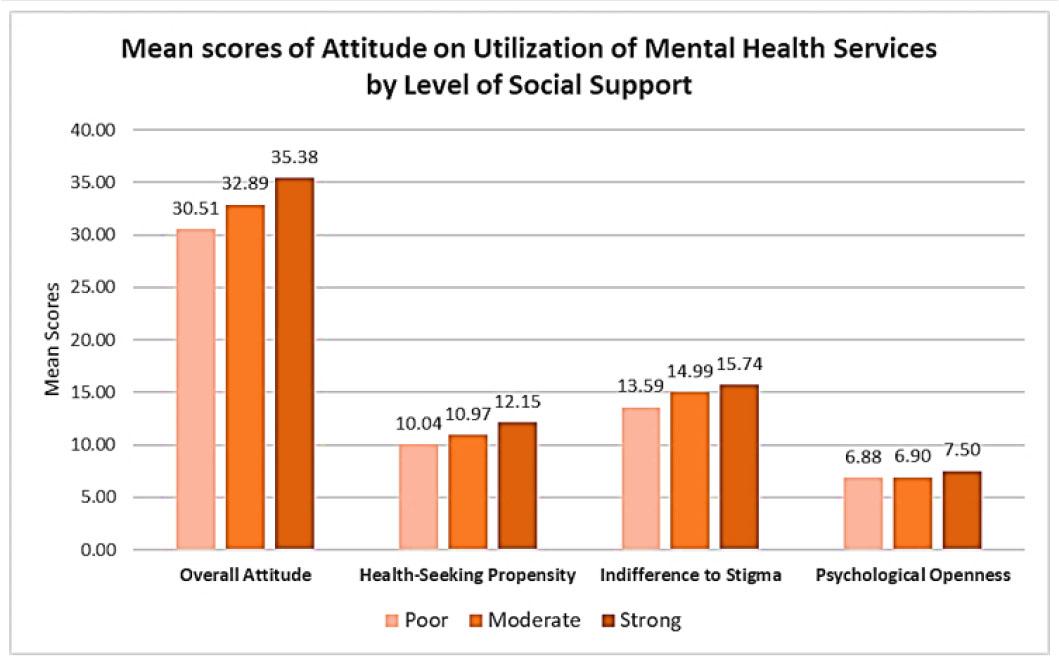

Figure 1 illustrates a clear trend indicating that higher levels of social support are strongly associated with more favorable attitudes (F (2, 328) = 18.05, p<.0001). This trend is consistent across two attitude subcategories: help-seeking propensity (F (2, 329) = 14.58, p <.0001) and indifference to stigma (F (2, 329) = 9.67, p<.0001). This suggests that stronger social support positively influences students' willingness to seek help and reduces concerns about stigma.

Comparative Assessment of Attitude and Level of Social Support on Mental Health Services Utilization

In contrast, the subcategory psychological openness shows no significant differences (F (2, 328)=1.58, p =.2082) increase in scores across support levels. This indicates that psychological openness is less influenced by social support compared to the other two subcategories.

Further, Spearman correFurther, Spearman correlation supports the association between social support and utilization of mental health services in (ρ= 0.130, p=.0175) and outside (ρ= 0.128, p=0.0197) the university.

Table 6 further supports that students with strong social support have the highest mean (12.15), compared to 10.04 for those with poor support.

Mean Scores of Help-Seeking Propensity Across Levels of Social Support.

| Poor | Moderate | Strong | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 10.04 | 10.97 | 12.15 |

| SD | 2.16 | 2.20 | 2.52 |

| Median | 10 | 11 | 13 |

Table 7 shows that only social support (p=0.017) showed a statistically significant relationship with the utilization of school-based mental health services, indicating that stronger social support increases the likelihood of utilizing these services.

Logistic Regression for Service Utilization In School and Mental Health Status, Attitude, and Social Support.

| Variables | Odds Ratio | Std. Err. | t-value | p-value | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.035 | 0.056 | −2.12 | 0.034 | 0.002 | 0.777 |

| Depression | 1.069 | 0.316 | 0.23 | 0.821 | 0.599 | 1.910 |

| Anxiety | 0.993 | 0.244 | −0.03 | 0.978 | 0.613 | 1.609 |

| Stress | 1.143 | 0.319 | 0.48 | 0.633 | 0.660 | 1.978 |

| Attitude in Utilization | 0.991 | 0.039 | −0.23 | 0.817 | 0.916 | 1.071 |

| Social Support for Utilization | 1.940 | 0.539 | 2.39 | 0.017* | 1.125 | 3.343 |

Log likelihood = −116.73301

LR chi-squared (5) = 6.55

p-value = 0.2560

Pseudo R-squared = 0.0273

Significant at p ≤ 0.05

Table 8 indicates that social support (p=0.009) showed a statistically significant relationship with the likelihood of utilizing external services.

Logistic Regression for Service Utilization Outside School and Mental Health Status, Attitude, and Social Support

| Variables | Odds Ratio | Std. Err. | t-value | p-value | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.000 | 0.000 | −4.27 | 0.000 | 4.70E | 0.011 |

| Depression | 1.553 | 0.533 | 1.28 | 0.199 | 0.793 | 3.043 |

| Anxiety | 0.944 | 0.273 | −0.2 | 0.842 | 0.536 | 1.663 |

| Stress | 1.449 | 0.456 | 1.18 | 0.238 | 0.782 | 2.687 |

| Attitude in Utilization | 1.085 | 0.049 | 1.79 | 0.073 | 0.992 | 1.187 |

| Social Support for Utilization | 2.264 | 0.713 | 2.6 | 0.009* | 1.221 | 4.197 |

Log likelihood = −92.465

LR chi-squared (5) = 20.90

p-value = 0.0008

Pseudo R-squared = 0.1015

Significant at p ≤ 0.05

However, mental health status (i.e. depression, anxiety, and stress) did not significantly predict service utilization in and outside the university. Despite some indications that higher depression and stress scores might increase utilization, these relationships were not statistically significant.

Mental health service utilization among students remains low, with only 12% (39 students) accessing school-based services and 9% (31 students) seeking help outside. A vast majority—88% to 91%—have never accessed mental health support from either source.

Among those who used school services (Table 9), most (67%) saw the Guidance Counselor or Coordinator only once. The main reasons for seeking help were difficulty managing emotions (19%), feelings of sadness or depression (19%), and negative thoughts (19%). Fewer students sought help for academic difficulties, teacher-related issues, family conflicts, anxiety, or peer concerns.

Mental Health Services Utilization in School

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Services Utilized | ||

| One-time meeting with Guidance Counselor or Coordinator | 26 | 66.67 |

| Group Counseling | 6 | 15.38 |

| Online consultation with a specialist or psychiatrist | 4 | 10.26 |

| Regular Individual Counseling | 3 | 7.69 |

| Total | 39 | 100 |

| Reasons for availing services | ||

| Difficulty in controlling emotions | 7 | 19.44 |

| Feeling sad or depressed | 7 | 19.44 |

| Having negative thoughts | 7 | 19.44 |

| Difficulty with a course or subject | 5 | 13.89 |

| Teacher-related issues | 3 | 8.33 |

| Conflict with family | 3 | 8.33 |

| Anxious about something | 2 | 5.56 |

| Conflict with friends | 1 | 2.78 |

| Others | 1 | 2.78 |

| Total | 36 | 100 |

Among the 31 students who accessed services outside the university (Table 10), the most consulted professionals were psychiatrists (27%), religious leaders (23%), and counselors (20%). Some sought help from psychologists, family therapists, barangay or community leaders, and one student from a coach. Common reasons included overthinking, sadness, anxiety, difficulty with emotions, and suicidal thoughts, alongside academic and interpersonal concerns.

Mental Health Services Utilization Outside School

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Sought out for mental health support | ||

| Psychiatrist | 8 | 25.81 |

| Religious Leader | 7 | 22.58 |

| Counsellor | 6 | 19.35 |

| Psychologist | 4 | 12.90 |

| Family therapist | 3 | 9.68 |

| Barangay/Community Leader | 2 | 6.45 |

| Coach | 1 | 3.23 |

| Total | 31 | 100 |

| Reasons for availing mental health support | ||

| Overthinking | 5 | 22.73 |

| Having negative thoughts | 5 | 22.73 |

| Feeling sad or depressed | 3 | 13.64 |

| Difficulty in controlling emotions | 2 | 9.09 |

| Anxious about something | 2 | 9.09 |

| Difficulty with a course or subject | 1 | 4.55 |

| Difficulty with working on a project | 1 | 4.55 |

| Conflict with family | 1 | 4.55 |

| Conflict with friends | 1 | 4.55 |

| Thinking of suicide | 1 | 4.55 |

| Total | 22 | 100 |

Table 11 summarizes reasons for not accessing services. The most reported barrier was the statement “I don't want to”—45% for in-school and 35% for external services—followed by uncertainty about where to get help.

Reasons for Not Utilizing Mental Health Services

| Reasons for not availing of mental health services | Did Not Avail School Services | Did Not Avail External Services | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. | Percent | Freq. | Percent | |

| I don't want to | 130 | 44.67 | 105 | 34.88 |

| Unsure where to go | 70 | 24.05 | 88 | 29.24 |

| Unsure who to see | 21 | 7.22 | 15 | 4.98 |

| Unsure if they can help | 20 | 6.87 | 12 | 3.99 |

| Have not heard about them/not aware of them | 21 | 7.22 | 14 | 4.65 |

| It is expensive | 5 | 1.72 | 33 | 10.96 |

| Not accessible | 7 | 2.41 | 16 | 5.32 |

| Others | 17 | 5.84 | 18 | 5.98 |

| Total | 291 | 100 | 301 | 100 |

The findings of this study indicate that a significant proportion of students at this university experience mental health concerns, reflecting a global trend of rising psychological issues among university students (Alibudbud, 2021; Cleofas, 2020; Dessauvagie et al., 2022; Kabir et al., 2024; Li et al., 2022; Lipson et al., 2019). These concerns pose serious implications at both the individual and institutional levels. Individually, students may experience poor academic performance, absenteeism, and psychological distress. Institutionally, the university may face declining retention rates and increased demand for psychological services.

However, despite these alarming trends, mental health service utilization remains low. Only 9% to 12% of students reported accessing mental health services, either within the university or through external sources. A vast majority—ranging from 88% to 91%—have never sought formal support. The most frequently reported barrier was the response, “I don't want to,” which may reflect reluctance rooted in self-reliance or the perceived ability to handle problems alone, fear of judgment or stigma, or lack of awareness (Muhorakeye & Biracyaza, 2021; Patte et al., 2024; Stanley-Clarke et al., 2024).

Nevertheless, the study directly addresses the research aim of predicting mental health service utilization by demonstrating that social support significantly influences students' attitudes toward mental health services, which, in turn, can shape their likelihood of seeking help. Specifically, analysis of variance shows that students with higher levels of social support exhibit significantly more favorable overall attitudes toward mental health services (F(2, 328) = 18.05, p < .0001). This trend is particularly evident in the subdomains of help-seeking propensity and indifference to stigma, suggesting that students who feel well-supported are more likely to seek help and are less concerned about stigma. This finding is consistent with a study among Turkish university students, which reported that positive help-seeking attitudes were associated with perceived support from parents and friends (Koydemir-Özden, 2010).

Moreover, the mean scores in Table 6 reinforces these findings, revealing that students with strong social support had the highest attitude scores (mean = 12.15), compared to those with poor support (mean = 10.04). Further, social support significantly predicted actual service use—both for school-based (p = 0.017) and external (p = 0.009) mental health services. These results are similar with findings from other cultural contexts. In the United States, students with stronger perceived social support were significantly more likely to access professional services (Eisenberg et al., 2013). In China, improving mental health literacy and perceived social support while reducing stigma can increase the likelihood of Chinese college students seeking professional psychological assistance (Yang et al., 2024).

Furthermore, a systematic review which examined studies from ten countries—including Australia, Canada, China, Indonesia, and the United States—found that social support mitigated symptoms of depression, anxiety, suicide, and psychological distress among 3,669 university students (Vicary et al., 2024). Although the review did not explicitly examine service utilization, it emphasized the foundational role of social support in promoting student mental health.

Interestingly, the study's logistic regression analysis revealed that mental health status—specifically symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress—did not significantly predict service utilization. This finding contrasts with the results of Lipson et al. (2019), who reported a strong link between psychological distress and help-seeking behavior. One possible explanation is that students experiencing high levels of distress may view available services as inadequate, inaccessible, or unhelpful. As a result, they may turn to alternative coping strategies such as peer support, self-help methods, or avoidance (Ravisankar, 2024). These tendencies may help explain the most frequently reported barrier: “I don't want to.”

Additionally, while attitude alone did not significantly predict service use, findings suggest that attitudes can be positively influenced by social support. Students who feel supported tend to adopt more favorable views toward help-seeking and show reduced stigma. This aligns with the study involving college students in Pampanga, Philippines, which found that greater perceived social support lessens the impact of self-stigma on help-seeking attitudes (Punla et al., 2022). Thus, enhancing social support systems within and around the university can serve as an effective and culturally appropriate strategy to improve mental health service utilization among students in higher education.

The use of validated instruments enhanced the reliability and consistency of the findings. A comprehensive five-month data collection period ensured broad representation across all year levels, enriching the depth of analysis. Moreover, the large sample size and application of stratified random sampling strengthened internal validity and minimized sampling bias.

Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. Response bias may have affected the accuracy of self-reported data, and the cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw causal inferences or observe changes over time. Important factors such as past trauma, academic workload, and family dynamics were not accounted for, potentially omitting key influences on mental health and service utilization. Additionally, students with severe mental health conditions or heightened stigma-related concerns may have been underrepresented. Cultural factors unique to Zamboanga Peninsula may also limit the generalizability of the findings to other student populations.

This study offers valuable insight for university administrators and mental health practitioners by identifying social support as a key factor influencing students' willingness to seek mental health services. While mental health concerns are widespread, service utilization remains low. Strengthening students' support networks—through peer programs, family engagement, and faculty training—can help reduce stigma, encourage help-seeking behavior, and improve student well-being and retention.

Despite the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among students, actual use of mental health services remains disproportionately low among college students in a university in Zamboanga City, Philippines. These findings must be interpreted within the study's limitations, including its cross-sectional design, limited geographic scope, and exclusion of qualitative insights.

Importantly, the study advances existing literature by integrating mental health status, attitudes, and social support as predictors of service use within a localized sociocultural framework of an educational institution. While mental health status and attitudes alone did not significantly predict utilization, social support emerged as a robust and consistent facilitator, indirectly enhancing attitudes by reducing stigma and increasing openness to professional assistance.

Moreover, the findings highlight the importance of strengthening social support systems within the university to bridge the gap between students' mental health needs and their actual use of services. The first initiative that the university can implement is using communication tools such as infographics, short videos, student testimonials, and printed materials with QR codes linking directly to university mental health resources. These should be displayed prominently across campus and shared via official online platforms. Second, actively involve faculty, staff, and students in mental health promotion efforts. Faculty members should receive regular training on how to identify students in distress and how to respond appropriately. They can also include mental health topics into their coursework or discussions to help normalize conversations around mental well-being. Third, strengthen external sources of support by involving families and religious or community organizations in mental health education. For instance, the university can host workshops for parents on adolescent mental health or collaborate with faith-based groups to promote supportive messaging around mental health.