The imperial temple

The woman, who is rearing a family of children; the woman, who labors in the schoolroom; the woman, who, in her retired chamber, earns, with her needle, the mite, which contributes to the intellectual and moral elevation of her Country; even the humble domestic, whose example and influence may be moulding and forming young minds, while her faithful services sustain a prosperous domestic state; each and all may be animated by the consciousness, that they are agents in accomplishing the greatest work that ever was committed to human responsibility. It is the building of a glorious temple, whose base shall be coextensive with the bounds of the earth, whose summit shall pierce the skies, whose splendor shall beam on all lands; and those who hew the lowliest stone, as much as those who carve the highest capital, will be equally honored, when its top-stone shall be laid, with new rejoicings of the morning stars, and shoutings of the sons of God. [1: p. 38]

This passage comes from Catherine Esther Beecher’s Treatise on Domestic Economy, by far the most widely used North American housekeeping manual, first published in 1841. In it, Beecher utilises an architectural metaphor to describe women’s contribution to building a structure which was in fact the size of the entire world. Written in a period of establishing a global hegemony for English-speaking colonial settlers, Beecher was addressing conservative middle-class women, the intended readers of the Treatise, and in doing so, was contributing to a widespread nineteenth-century understanding of homemaking as a realisation of a religious and moral – and here cosmological – calling. Yet this metaphor also established a symbolic connection between domestic economy and the imperial ‘domestication’ of the entire world.

Much is already written about the calling that Beecher is framing through her architectural metaphor – namely, the role women played in settler colonialism. Authors have talked about the white patriarchal household as the nursery for colonial identities; the connections between imperial statehood and the quotidian, domestic, and intimate; or the home as a site in which Victorian values were established [2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9]. Through this essay I will add to this discussion by looking at the architectural work of women in building the ‘glorious temple’ of colonialism, not merely as a metaphor, but also as a material practice. In other words, it will explore how ordering, maintaining, and decorating the space of the home contributed to imperial political and spatial constellations as well as the ways in which the self-representation of this concrete, non-metaphorical labour of homemaking contributed to female colonial identities.

The period addressed by the essay is the one which Eric Hobsbawm famously described as the transition from ‘The Age of Capital’ to ‘The Age of Empire’. This involved a world-wide entrenchment of colonial capitalist exploitation by means of statehood; a period marked by ‘a systematic attempt to translate invasion and supremacy … into formal conquest, annexation and administration’ [10: p. 57]. Geographically, I will be looking at the domestic landscape on one of the fringes of the British Empire, the Pacific Coast ‘frontier’ of British Columbia. After the founding of the Colony of British Columbia in 1866, it then joined the Canadian Dominion in 1871. At this crucial moment, Canada finally realised its Biblical destiny as an imperial domain which spread from ‘Sea to Sea’, or, as the Canadian official motto goes, ‘A Mari usque ad Mare’.

Imperial annexation went hand in hand with promoting white domesticity as a symbol of civilisation, morality, and piety. Large-scale dispossession of the Indigenous population, sanctioned by the colonial Canadian government and reinforced by coercive means [11], simultaneously involved establishing Victorian domesticity as a micro-political instrument of fortifying imperial rule [12; 13; 14]. It was during this period that the Canadian government called for the mass immigration of women of Anglo-Saxon origin, as a measure against the homosocial and mixed-race relationships which has characterised previous life on the ‘frontier’, the white patriarchal household becoming not merely a symbol of moral uprightness but also of belonging to British civilisation.

Glimpses

I will start my exploration with three objects. The first is a letter from November 1874, in which Emma Crosby, a missionary wife living on the Northern British Columbian coast, describes her life and missionary efforts to her mother in Ontario (Figure 1). The second is the photograph of Charlotte Kathleen O’Reilly, an unmarried woman from a high-ranking family in Victoria, in which she poses as a gardener (Figure 2). The third is a watercolour painting featuring a home interior arranged by its painter, Josephine Crease, an artist and home decorator (Figure 3). Using minor literary and pictorial genres of letters, a private photograph, and watercolour, respectively, these women captured their work on cleaning, decorating, classifying domestic spaces by use, tending to home and garden, organising the form according to aesthetic standards of the time.

These objects are located in repositories of colonial culture – State-sponsored historical archives – of British Columbia and the University of British Columbia. Historically understood as repositories of ‘objective’ knowledge, these archives can also be considered a self-representation, a self-portraiture of the colonial society – assemblages of all things deemed important as traces of collective experience. In other words, not merely bodies of indexical evidence, as nineteenth-century historical norms would establish them to be, but, as Stoler would put it, ‘supreme technology of the late nineteenth-century imperial state’, as its supposedly objective trace [15: p. 57].

Figure 1

Letter from Emma Crosby to her mother dated 2 November 1874 (Courtesy of the University of British Columbia Archives).

The three artifacts that I found hold a special place in this vast system of self-representation. They are clearly subjective, as female self-portraits as homemakers – a letter about managing the household, a photograph of watering the garden, a picture of a well-ordered drawing room created by the one who made it. But it is precisely the ‘subjectivity’ of these images that offers us glimpses into ways in which women crafted their identities, tied their understanding of the household to the politics of Empire, and articulated those identities as a function of domestic space-making labour. My efforts to engage with these objects focus on them as remnants of a search for identity through parallel activities of homemaking and its representations.

Figure 2

Photograph in 1890 of Charlotte Kathleen O’Reilly watering the gardens at Point Ellice House, this being the O’Reilly family residence (Courtesy of the British Columbia Archives).

House and empire in the mission house

I will start this exploration by looking into the intimate epistolary opus of Emma Crosby, a missionary wife. Her letter of November 1874 belongs to a larger body of work – the letters to her mother that describe her life in a Methodist mission in the North British Columbian settlement of Fort Simpson (Lax Kw’alaams), founded by Emma and her Husband. The letters, written from 1874 to Emma’s mother’s death in 1881, are preserved in University of British Columbia Archives, and published in 2006 with commentary by Jen Hare and Jean Barman [16]. They describe Emma’s effort to establish what she understood as a Christian home on the frontier. Emma sends her missives at every arrival of the steamer Otter that connected Fort Simpson with the rest of the settler colonial world. In them, Emma primarily describes her relentless work – washing and ironing, ordering carpets, matching colours and fabrics in the home, securing winter supplies of flour, sugar, biscuits, hams, tea, coffee; ordering shawls and mending them.

Figure 3

Corner of the drawing room at 18 St Mary’s Road, Leamington in September 1890, as drawn by Josephine Crease (Courtesy of the British Columbia Archives).

Thomas Crosby’s Methodist mission, founded in 1874, had as its goal moral and spiritual as well as economic integration of the Indigenous population into the Dominion. As he worked on converting the Tsimshian, the Nisga’a, the Haida, and the Gitxsan, while his wife managed the household and the church school. Their two enterprises – male and female, were materialised in two buildings emblematic of the mission – church and the mission house (Figure 4), both designed by an architect from Victoria, Thomas Trounce, as a donation to the mission, and emblematic of British ‘taste’ that was supposed to impress and aesthetically convert Indigenous people [17]. The house and the church were connected to two bodies of literary work – Emma’s letters are one. The other is Thomas’s memoirs of his itinerant work on ‘converting’ First Nations all across the region [18; 19], described by fellow Methodist preacher and writer, Alexander Sutherland, as ‘laying the only foundations on which an enduring civilization can rest, and are better entitled to the name and fame of empire-builders’ [20: p. iv].

Figure 4

The Methodist church and mission house in Fort Simpson in the mid-1870s (Courtesy of the British Columbia Archives).

The connection between domesticity, piety and imperial conquest that defined the work of missionary wives [21; 22; 23; 24; 25] was, In Emma’s case, materialised in the model household she was making, and which was on display to the Tsimshian people who were frequently invited to inspect the premises. Much of Emma’s decorating and arranging work was meant to demonstrate her competence in domestic categorisation – itself an expression of European capacity for disciplined thought, a domestic mirroring of European post-enlightenment epistemology. This contrasted with Indigenous one-room log houses of fluid and mixed use, which the Chairman of the Methodist District of British Columbia, William Pollard, considered in need of ‘complete revolution in style … and domestic arrangements’ [26: p. 56].

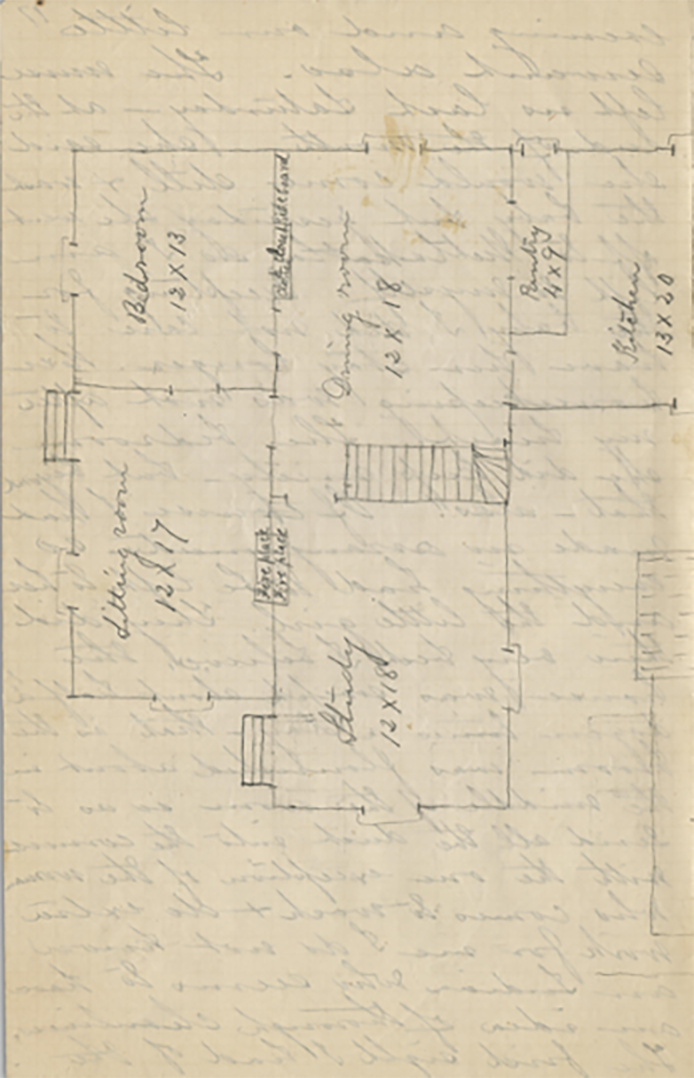

Figure 5

Plan of the mission house drawn by Emma Crosby in a letter to her mother dated 5 January 1875 (Courtesy of the University of British Columbia Archives).

Let me now discuss the idea of ‘domestic arrangements’. In a letter written to her mother during the period between 5th January and 11th February [27], Emma encloses the sketch of the house plan (Figure 5). What the plan shows is not merely the layout of the new abode, but also Emma’s Western competence in understanding spatial categories and architectural divisions that accompany them. Her letters testify to how, by applying particular rules of decorating and organising objects, she works on translating these categorisations into visual and haptic experiences and an order of things, in a manner consistent with the general Victorian female endeavour of translating ‘the ideology of a perfect home’, at the core of British middle-class identity [28: p. 9], into physical reality.

In her letters, Emma devotes special attention to the furnishing of spaces which were customarily understood as female – bedroom and sitting room (or parlour). She describes the bedroom to her mother:

You ask if we have a ‘good bed’? ... It is as good as I ever slept on I think. The bedstead is a new one and quite pretty one we got in Victoria. The mattresses we got there too. It is made of something similar to wool. The bureau has a large oval glass, marble top and white knobs – the washstand of an approved pattern. So with the new carpet and some of Auntie’s little mats and your nice one bedside the bed, it is a cosy little room. [29]

The ‘cosy’ space of familial conjugal intimacy, the bedroom, is complemented by the space of female solitude, a ‘bright’ sitting room, with ‘bright carpet’ and ‘a green lounge in it, an oval center table and a little stand, a rocking chair’ [29]. In contrast to the bedroom and the sitting room, dining room and study, gendered as masculine, were supposed to convey respectability and are ‘plainly furnished’, and ‘hung with pictures and maps and contains the book cases and an oval table’, as well as a variety of objects, such as a stereoscope and magic lantern, meant to impress the Tsimshian visitors.

Labour qua labour

The goal of Emma’s work was to uphold the standards of the Victorian household on the frontier. It involved maintaining the architectural arrangements which were part of British middle-class identity as fundamentally architectural, as Tange stressed in her analysis of Victorian literature [28]. This is concrete labour of buying things, sweeping the house, organising objects, a female architectural endeavour that is inseparable from other activities aimed at maintaining the physical and symbolic space understood as ‘home’. In her letters Emma expressed pride in her knitting and crochet work, skill in repurposing clothing, mending stockings, sawing pinafore aprons for her daughters. Her letters provide fascinating details about the Anglo-Saxon diet on the colony’s edge, with Emma baking bread and complementing local food staples – fish, venison, and clam – with fruits and vegetables from Victoria by steamboat – cherries, apples, tomatoes, green peas and beans, pears, and plums – and how she churned butter from the milk of their cow.

The spatial work Emma was performing as the organiser and classifier of domestic spaces is inseparable from her work on home upkeep, on home maintenance, and those together are the female parallel to the architectural act of erecting the mission house performed by Thomas Trounce and Thomas Crosby. In many ways, this was a work of minor, shadow architecture, key to translating the building into what Emma and other women of her age understood as ‘home’.

Descriptions of housework absolutely dominate Emma’s writing which, it can be deduced, had one important goal – to assure her mother (and possibly other relatives to which the letter was read) that Emma was a hard worker, relentlessly toiling to uphold the standards of a proper middle-class household on the frontier. Let us look for a moment at the nature and importance of this labour within the larger historical context. The best analysis of the relationship between capitalism and Protestant self-understanding is still that established by Webber, who writes that at the essence of Protestantism is the cult of work, which corresponds to capitalist aversion of idleness of both labour and capital [30]. According to Webber, that Protestantism is a fundamentally capitalist religion as it condemns idleness of both people and capital and thus stimulates both labour exploitation and capital growth. Webber isolates three tenets of Protestantism in the service of this main idea. One is the promotion of work as an end in itself, with laboriousness presented as godliness. The other is that it develops the notion of work as ‘calling’, as fulfilling a higher purpose and giving life meaning. The third is that it promotes asceticism and thrift, ascesis as indicative of productivity (that is, absence of leisure).

All three are the principles of Emma’s life. She works all the time and understands herself as a labourer; she sees her work as part of performing a larger calling; her work is epitomised in her judicious and thrifty management of the home. As an expression of protestant spirit, Emma’s homemaking work was the microcosmic complement her husband, but potentially a superior one. It was work without end, a goal in itself, not justified by any kind of outcome or product, relentless, indefinite. And, as such, it was both a better manifestation of the capitalist ethos than that of her male counterparts and defined her as the labourer qua labourer – in Protestant context, the epitome of piety.

Inside and outside

On the spiritual, economic, and administrative ‘frontier’, Emma’s domestic toil – as a manifestation of both piety and the nascent capitalist spirit – was constantly on display to the Indigenous people she was trying to convert. Home was part of the colonial ‘exhibitionary complex’ [31; 32]. It is crucial that what was on display was not only classifications of space, ‘civilised’ object assemblages, but also labour itself. Emma described her work to her distant family; but work was also what Macketlow calls, writing about missionary wives, a ‘public performance of [spiritual] agency’ [33: p. 151]. Emma saw her role in the Tsimshian community not as that of formal spiritual conversion (this was left to Thomas), but instead that of mothering, as manifested first and foremost in her guardianship over her Tsimshian ‘charges’ – girls that she took into her household to supposedly ‘protect’. These young women who were left there usually by their relatives to gain skills and social knowledge that would be helpful in the context of the dispossession and marginalisation that colonialism produced, were trained in gendered labour – cooking, knitting, cleaning, childcare. This training was supposed to culminate in marrying them off as competent housewives and having them establish their own Christian households and become part of Anglo-Saxon ‘civilisation’ that the nascent Canadian state was supposed to represent.

Emma describes ‘charges’ as inferior and in need of her supervision and guidance. Her criticism would be articulated in passages such as this one, describing the situation where an Indigenous woman cleans the house while Emma is taking care of her newborn baby:

Her housekeeping was not after my heart. The bedroom she did keep nicely – but beyond that, alas! Of course I had made no arrangements so everything had to be left to her and the little girl. They did their very best, I believe, the house was swept about half a dozen times a day – that is the broom was flourished about the middle of the room so as to send all the dust into the corners. With the one exception of the woman who comes to wash & do extra work for me I do not know an Indian who seems to have an idea of thorough cleanliness. [29]

Emma’s ‘domestication’ in this context had two simultaneous connotations, which correspond to the dynamic between interiority and exteriority that Amy Kaplan has written about. Kaplan points out that there is a double structural opposition at the heart of the imperial project. It is the opposition between the domestic and the public coupled with the opposition between domestic and the foreign. In Kaplan’s words, domesticity ‘makes manifest the destiny of the Anglo-Saxon race, while Manifest Destiny becomes in turn the condition for Anglo-Saxon domesticity’ [6: p. 597]. As a missionary, Emma was performing double domestication in the household – creating the private sphere and creating the domesticated Indigenous subject.

Emma’s dissatisfaction with her ‘charges’, and here ambivalence about their presence in the home, especially after she had her own biological children, points to contradictions that plagued the Imperial project of domestication at large. Like all colonisers, the Crosby’s wanted, at the same time, to fold the ‘Indians’ into white ‘civilisation’, on the one hand, and yet to preserve racial boundaries on the other. In this situation, the Tsimshian were neither inside or outside the imperial realm, and, correspondingly neither inside nor outside the colonial home. In Emma’s household, this dynamic was manifested by her simultaneously feeling that she had a duty towards her Indigenous ‘charges’ set against her mistrust of them. By bringing them into her home, she was trying to incorporate the outer world into her motherly Imperial domain; but by also portraying them as less competent and less trustworthy, she was contracting her domestic sphere to assert white domestic superiority. As time progressed, her fear of the bad influence of Indigenous women on her biological children increased, up to the point where she established clear racial boundaries between her biological and metaphorical, Indigenous progeny. This ultimately resulted in establishing, what Emma called a ‘Home’ (in quotation marks), as an addition to their house where girls would be schooled in household labour, and which eventually became a girls’ school.

Emma’s process of negotiating and redefining what and who was inside her domestic realm, and what was outside, as well as creating threshold spaces such as her ‘Home’, reflected similar negotiations in the macrocosm of the British Empire, and its spatial codes, distinctions, boundaries, as well as showing that the nature of domesticity had to constantly be re-established. In this sense, cyclical female work and the female ordering, re-ordering, maintenance and negotiation of the boundaries within domestic space – Emma’s ‘minor architecture’ of domestic reproduction – served, in her case to enforcing the double figure of domesticity that defined Victorian culture in Britain’s colonial frontiers, with all their inherent contradictions.

Lady with a garden hose

Emma Crosby’s domestic labour constantly negotiated the boundaries between inside and outside in a double sense: that of the space of the single-family home and also of macro-spatial imperial dynamics embodied in her relationship to Indigenous servants and protégés. There were also other important kinds of spatial negotiation – the relationship of the buildings to the ground, the relationship to the site, and the reverberation between microgeographic and macrogeographic practices of siting the building.

Another archival glimpse into the world of colonial domesticity is offered by the 1890 photograph of a woman in the gardens of a house in Victoria. The woman poses in a straw hat and informal attire as she uses a hose to spray a non-manicured field of flowers, divided by a fence from a tree- and bush-lined landscape in the background. This is the portrait of the lady as a worker. Rather than posing in her Sunday best surrounded by a carefully composed set of allegorical objects, or by her family, as was customary in Canadian female portraits at the time, here she is set within nature and is presented spontaneously as being fully in the moment, as a woman of action.

The woman in the photograph was the daughter of Peter O’Reilly, a County Court Judge and Indian Reserve Commissioner. The garden in which she poses (still preserved as a heritage site based on an avalanche of preserved documents) was established by her father in 1862. After he advanced in official roles, so he left the garden increasingly to his daughter’s care. Charlotte – who never married and had no children – applied her ‘feminine touch’ through her assigned caretaking role as the gardener of the family residence, Point Ellice House, a role she performed from the 1880s until her death in 1945.

The garden in which Charlotte posed belongs to a time when the British Columbian elite started erecting single-family houses in their provincial capital to signal the act of permanent settlement and to convey their own privilege as leaders in the colonial enterprise. Segger calls these houses, which were meant to mimic European architecture with its longevity and rootedness, the ‘architecture of permanence’ [34: p. 16]. They were created from the 1860s through the end of the century, transforming Victoria into what contemporaries described as the ‘city of homes’ [34: p. 23].

Indeed, we know that the exact year in which Peter O’Reilly erected Point Ellice House, designed by architects John Teague and W. Ridgeway Wilson as one of the first European-style mansions in the city, was 1861. But whereas the construction of this house can be understood as an architectural event, rooted as a built condition, it also needed to be maintained through continuous, repetitive work of cultivation and care. Charlotte O’Reilly, in her care of the garden’s plants, supplied this kind of labour. Yet how did Charlotte’s tilling, cultivation, and maternal care, relate to larger narratives of gardens represented by the site’s colonial relationships? How did it translate these imperial narratives? And what was the status of Charlotte’s seasonal, cyclical labour – as a minor architecture – reflect the architectural and geopolitical enterprise of marking annexation and settlement of the Pacific Frontier?

Empire as garden

The garden is one of the key metaphors in Canada’s imperial story of ‘discovery’ and ‘possession’. As early as the mid-seventeenth century, reports sent back by Jesuit missionaries portrayed the ‘New World’ as a pre-Lapsarian garden – indeed, a paradise [35]. For example, Pierre Biard, writing for a French audience about ‘New France’, described Canada as an immensely fertile land which possessed a great variety of fruits and exotic delicacies. His notion was both scriptural and agricultural, symbolic and concrete. Jesuit missionaries, was well as admiring the lushness and beauty of the frontier landscape, tried literally to grow many different kinds of crops – peas, beans, vegetables, and so on – as if they were testing the fertility of their paradise. At the same time, they were keen, according to their own accounts, to convert Indigenous people in fulfillment of their destiny as the ‘pure’ Christian inhabitants of this latter-day Eden. And their method to do so was through agriculture.

Some two centuries after Pierre Biard’s writings, when the Canadian Pacific Railway connecting the Atlantic East Coast to the Pacific West Coast had been completed, the ‘frontier’ of British Columbia was conceptualised as a ‘garden’ sitting behind the Canadian imperial ‘home’. Frederick Arthur Talbot, a Canadian writer on railway travel and cinema, expressed this idea most directly in his 1911 book on The New Garden of Canada: By Pack-Horse and Canoe through Undeveloped New British Columbia [36]. The text offered an account of his trip to this ‘untouched corner of the Empire’, with the riches of its natural world ‘lying dormant, and silently calling to the plucky and persevering’ [36: p. vii]. Hence the land in Canada was presented as both a heaven for resource extraction – mining, lumbering, agriculture – as well as a beautiful destination for touristic sightseeing.

The capacity to till the soil of this imaginary garden, which was in itself cyclical and repetitive work, formed the basis of imperial land claims. The difference between Indigenous people and the white settlers had been framed from the beginning as a difference precisely in their capacity to cultivate. As early as 1831, in his famous text on Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville linked the pending disappearance of the native ‘Indian’ to their aversion to work, something that they ‘consider not merely an evil but as a disgrace’, especially in terms of their disgust for ‘the constant and regular labor which tillage requires’ [37]. This understanding that the Indigenous people were indolent and lazy in the sense of not engaging in tillage became the argument to justify land dispossession. The man who was most responsible – Joseph Trutch, a surveyor who became the Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia – for example asserted the falsity of ‘the claims of Indians over tracts of land, on which they assume to exercise ownership, but of which they make no real use, operate very materially to prevent settlement and cultivation’ [38: p. 9].

‘The Queen’s Gardens’

The notion of the garden first mentioned in Jesuit narratives about Canada, and then taken up in colonial narratives of British Columbia, was hence a potent metaphor which framed the relationship between the white settlers and First Nations peoples. It was complex in that it simultaneously referred to two aspects: a Biblical sense of Eden as a site of economic fertility wherein the land was amenable to exploitation and cultivation, as well as the site’s Edenic beauty in terms of its picturesque qualities.

In Victorian literature about gender, the metaphor of the domestic garden was likewise complex. Gardens were where gentile identity was crafted, with the flower garden especially being a locus where women performed their nurturing role in public [39]. Women were also themselves ‘gardened’ – an entire body of nineteenth-century literature presented them as ‘delicate, frail flowers to be watered and cared for, as well as “gardeners” themselves, capable of caring for others once they are properly tended to’ [40]. Perhaps the most notable use of the garden metaphor to refer to women’s capacity to care and be cared for came in John Ruskin’s lecture on ‘Sesame and Lilies’, in which he described the ideal Victorian home as ‘The Queen’s Gardens’ [41]. The key topic of his speech was the importance of educating women in a way that would cultivate their hearts rather than their minds, enabling them to be the ‘helpmate’ of men. Once tended to as a ‘lily’, a woman would become capable of transforming her home into a garden: ‘the place of Peace; the shelter not only from all injury, but from all terror, doubt and division … a sacred place, a vestal temple, a temple of the hearth watched over by Household Gods’ [41: pp. 148–149].

Ruskin’s writings were well known among Canada’s upper classes, and by the 1880s served as guide for women’s education, especially in the gentile societies of its east coast provinces. In Montreal, the reception of Ruskin’s idea of the ‘lilies’ fed into the production of photographs of girls and young women which expressed pride by showing these daughters (but not their mothers) in ‘queenly’ situations in front of a book or a painting, testifying to their genteel education [42].

Figure 6

Photograph in 1890 of Charlotte Kathleen O’Reilly on the pathway in between the gardens at Point Ellice House (Courtesy of the British Columbia Archives).

In contrast to the more dynamic photograph of her with a hose, most of the portraits of Charlotte O’Reilly in the garden, such as another one also taken in 1890 (Figure 6), followed this gentile genre of portraying daughters. Strolling in the cottage garden behind the house, dressed in her finest attire, Kathleen was presented as an educated young lady who could admire the garden scenery. In this way, Charlotte is made into a part of the garden – as a lily rather than a gardener, with the photograph helping, as Dianne Lawrence would put it, to ‘formulate site-specific forms of genteel identity’ [39: p. 135].

Charlotte’s photographs belonged to a genre which had only just appeared in British Columbia – the private portrait. Previously, the initial use of photography had been for colonial administration, surveying the land and recording its inhabitants as ‘objective’ rather than symbolic depictions of reality [43]. Symbolism and ‘subjective’ portrayal in photographs were only introduced through commercial photography, which picked up after the founding of the Canadian federation, through the exertions of Hannah and Richard Maynard, Frederick Dally, Oregon C. Hastings, Charles Gentile, Edward Dosseter, and Benjamin Leeson. By posing for these domestic portraits, the middle-class Anglo-Saxon settling women were displaying themselves as mothers in an attempt to capture them and their children as participants in the birth of the nation [43].

Thus, in these two different photographs from 1890, Charlotte O’Reilly was shown both as an object of beauty in her father’s garden, a Ruskinian ‘lily’, but also in her motherly role as cultivator who could make the garden and awaken its fertility. In the former photograph, Charlotte appreciates the beauty of the landscape around her house in the same way that an explorer or tourist would when they encountered the supposedly ‘virgin land’ in Canada’s Pacific frontier. In the latter action portrait, however, this frontier woman presented herself as part of the colonial process of resource extraction. Her effort to capture herself in these two completely different roles was a negotiation between her microgeographic (domestic) and macrogeographic (imperial) relationship to the site on which Point Ellice House stood. Charlotte’s self-representations – as connoisseur and worker – reflected the contradictory rhetoric of Canada as an imperial garden both to behold and to exploit.

A portrait among things

I would now like to turn another ideological issue in British imperialist culture with architectural and spatial manifestations: namely, an anxiety about consumption, and especially about the acquisition and ordering of objects, which stemmed from a contradiction between Protestant aversion to indulgence and the demand to purchase domestic objects as a necessary requirement of capitalism. Dealing with this anxiety was one of the main tasks of the minor architecture of interior decoration with the home, a terrain of female expertise. This expertise involved, first and foremost, acumen in how to acquire things as part of the awareness of their material qualities and symbolic meaning – but then also the capacity to arrange these objects in a manner that demonstrated education and refinement, to reveal character and imperial identity, and of how to morally influence the behaviour of inhabitants and visitors [39]. It was their relationship to objects, and the ability to create object assemblages, which turned Canadian women into creatures of sophistication and good taste while also expressing geopolitics within the microenvironment of their homes.

Figure 7

Interior painting of the room occupied by the Crease sisters at no. 29 Alexandra House in November 1890 (Courtesy of the British Columbia Archives).

To explore how this worked in the particular context of the Canadian ‘frontier’, one can look as the watercolour painting of a drawing room created by an upper-class painter in Victoria in the 1890s. The image was created by Josephine Crease, daughter of Sir Henry Crease, a British-born and Cambridge-educated settler who became a member of the Supreme Court of British Columbia in the 1870s. Josephine was schooled at King’s College in London along with her sister Susan, also a watercolourist. Josephine’s painting is part of a larger series that does not include her, but which reveal the object arrangements in the intimate spaces she inhabited (Figure 7). What is particularly interesting in this instance is that Josephine figures both as the maker of this interior and the painter of the interior she made. This negotiated her artistic and decorating expertise as two kinds of aesthetic work. Although she is absent from the painting, Josephine used the image to assert her identity as a woman and a colonial subject, creating a particular sensory environment.

Josephine Crease’s watercolours thus display a wealthier and more sophisticated version of Emma Crosby’s parlour, with the painter’s identity being projected through her choice of books, urns, dishes, artworks, mirrors, books, curtains, tablecloths, chairs, tables, candlesticks, vases, mirrors, cushions, drapes, lamps, tea sets, and countless other knick-knacks – all of them mass-produced objects that Josephine would have acquired as a consumer from Canada’s upper class.

The morality/immorality of consumption

Literature on Victorian interior decoration and its connection to ‘character’ stresses the importance of the choice and arrangement of objects. In the imperial context, such objects were not just a neutral means of negotiating female identity; instead, they also were laden with ethical, economic, spiritual baggage, creating contradictions that were not easy to solve and yet which framed Josephine Crease’s efforts.

The problem with acquiring and consuming objects within that historical context was the contradiciton between the need to demonstrate wealth, culture, and status, while simultaneously regarding consumption as ethically suspect, a product of leisure and waste that was antithetical to the Protestant work ethic. This applied not only to domestic decoration but also to the whole object-dynamics of the British Empire, whereby the circulation of commodities and the capacity to acquire goods from across the globe was simultaneously a sign of British power and its profligacy [44]. There was hence a conflict between the fruits of capitalism and what Webber called its ‘spirit’ [30]. Wealth resulting from imperial dominance was celebrated, while at the same time Christian missionaries, who provided colonial expansion with ‘spiritual’ ground, bringing it into the domain of the most intimate relationships, warned sternly against excessive consumption.

Western imperialism thus meant conversion to varieties of Protestant religion that condemned surplus and waste, as well as inculcating a taste for western goods. Britain considered itself to be privileged by God due to the volume and extent of its trade, and to its ability to ‘domesticate’ frontiers in Canada and elsewhere [44: p. 126]. Yet at the same time, consumption was immoral, according to Protestant norms, creating a particularly schizophrenic condition. In The Protestant Ethic, Webber talks about ‘ascesis’ as the third key element of the Protestant ‘spirit’, in addition to the sanctification of work and the idea about labour as one’s calling. But what does ‘ascesis’ mean in the context of the British Empire? My hypothesis here is that ascesis did not necessarily mean abstinence from consumption, but rather the imposition of aesthetic rules onto the acquisition and arrangement of objects to present these collections as rational and disciplined.

The significance of these aesthetic rules was all the more pertinent on the British Empire’s frontiers, where the relationship to objects was particularly fraught and emblematic of colonial relationships. In the Pacific northeast at the dawn of Canadian/British Columbian statehood, great care was put into distinguishing the display of objects according to British middle-class taste as a sign of capitalist civilisation from the wasteful attitude towards objects in the barbarous Indigenous gift economy, typified by the potlatch tradition of winter festivities whereby things such as blankets, masks and pottery were given away as an expression of wealth and power. For example, donors who provided missionaries with funds to ‘civilise’ Indigenous peoples, such as those who paid for Dr Bertrand Wilbur’s western-style model cottages for the Tlingint in Alaska in the 1880s and 1890s, were assured by the fact that the ‘cottages are, in fact plain, but have both comfortable and aesthetically pleasing decoration’ – possessing ‘a carpeted, sofa at one side, rocking chairs, table and book case, as we -should find in any comfortable home’, along with ‘a cabinet with some pretty china and a few odd trinkets treasured by the family’ and some ‘bedsteads and the usual furniture’ [45: p. 164]. In contrast the potlatch was portrayed by colonisers as being ‘primitive’ because it was wasteful of resources, which should be accumulated and not given away, and of time, which would be better spent in productive work [45].

The empire of things

Josephine Crease’s paintings of domestic interiors were inspired not only by the impetus to articulate a ‘civilised’ relationship to objects but also by middle-class manuals such as Isabella Beeton’s Housewife’s Treasury of Domestic Information, a volume of more than a thousand pages first published in 1865, which advised women on every possible aspect of home management from gastronomy and clothing, needlework, ‘toilet’, hiring servants, through to facial care and the choice of games for leisure hours [46]. Its largest section was dedicated to how to decorate various rooms and how to develop expertise in buying objects like carpets and rugs and furniture – the essential components of well-appointed home. The Housewife’s Treasury was the ultimate consumerist manual for an imperial world, discussing as it did the best way to purchase mass-produced goods such as ‘musical instruments, paintings, statuary, a portfolio of engravings’ [46: p. 58] that were being made available through industrial development and colonial expansion.

Isabella Beeton also shared knowledge about art history, politics and aesthetics in her book. She detected in the history of furniture a lineage of progress which relied on the capacity to acquire furniture from distant lands through imperial might from the ancient Romans onwards. Hence, one can find in her housekeeping manual passages such as the following:

A history of furniture would in great measure be a history of progress of the human race. Perhaps the rude cave-dwellers, whose only tools and weapons were a few roughly-chipped flints, were content with the grassy turf of white sand as a seat by day and couch by night … At the very dawn of authentic history we find races wildly differing in other matters yet at one with regard to the furnishing of their dwellings with articles of necessity or luxury. As has been well said by Dr Sampson, ‘In Egypt’s early history, however, as seen from distance, in the life of Joseph, the bedchamber was provided and the banqueting hall furnished as in later ages. In Homer, we read of Agamemnon’s “gilded throne”, of Juno’s “golden couch”, of Helen’s “loom”, and Hecuba’s “odoriferous wardrobe”.’ There is not an age in the chronicles of man’s existence, nor a land of his abode now visited, where substantially the same wants to household furniture are not met, and where art does not seek to give beauty to articles designed to meet this demand. [46: p. 231]

In addition, Beeton linked an increase in the luxury of home furnishings to imperial expansion, citing Paul Lacroix in support:

In subjugating the East, the Romans assumed and brought back with them extreme notions of luxury and indolence. Previously their bedsteads were made of planks, covered with straw, moss, or dried leaves. They borrowed from Asia those large carved bedsteads, gilt and plated with ivory, whereon were piled cushions of wool and feathers, with panes of furs and the richest materials. [46: p. 236]

She also referred to the 1851 Great Exhibition as a model display of objects created by British industry and conquest that the housewife should adopt as a source of inspiration. As a ‘collecting animal’ [46: p. 286], as Beeton described her, the British housewife had to be familiar with porcelain, antiques, venetian glass, statuary, and other industrial products. Yet as an imperial subject in a consumerist universe, she had to be equally familiar with, for example, the difference between Turkish, Aubusson, Kidderminster, and Axminster carpets [46: p. 250].

Ascesis

Josephine Crease was clearly obsessed with things. In her diaries she does not focus on social events, like most upper-class women in British Columbia at the time, but upon inventories and descriptions of household objects. She thus not only listed them but attempted to establish a system of things, a discipline whereby she could relate to them through colour coordination – a system that connected the subject and the object, the painted with the painting.

Isabella Beeton likewise sought to establish a direct connection between painterly and homemaking knowledge. She described home decoration as an art, quoting Lacroix, Pugin, Owen, Plato, and referred for example to Pugin’s rediscovery of Gothic design as a watershed moment in nineteenth-century history, leading to the provision of Gothic Revival furniture [46: p. 244]. She also realised that a knowledge of colour was essential to link art to the home, so she recommended housewives to read the work of Owen Jones, who had established order within the chaos of the Crystal Palace by colour-coordinating its interior and then elaborated on his ideas in his classic book, The Grammar of Ornament [47].

It is interesting to see how the colour-coding of the Crystal Palace, as a monument to the British Empire, trickled down into the aesthetics of Victorian home interiors in Britain and its colonies as small-scale settings for displaying imperial riches – albeit in a more restrained, disciplined, and ascetic manner. Isabella Beeton, expanding upon Owen Jones, provided her readers with instructions on how to choose the colour of wallpaper, upholstery, furniture, and carpets as the most essential elements of interior decoration. She thus helped to introduce the idea of ‘complements’ (such as green and red, or yellow and blue, as featured in Josephine Crease’s watercolours), and of secondary colours, and of tertiary colours (citrine, russet, olive, etc).

Josephine Crease’s fascination with household objects in her diaries was matched by her painterly fascination with colour coordination, suggesting that the main aim of her interior watercolours was not really the formal arrangement of things but the juxtaposition of colours to follows Jones’s and Beeton’s principles. London-schooled Josephine would have been familiar with those books. Thus, we can see deliberately contrasting hues of purple and yellow, red and green. Drapery, wall surfaces, and upholstery are all carefully matched. Her watercolours and her colour coordination show Crease as capable of both physically creating and representing the home, her identity being formed in the oscillation between these two endeavours. By removing herself from her paintings, and instead projecting herself through objects, she was, of course, reifying herself through her self-identity with the world of goods. Yet through painting, she also managed to be an observer of the domestic realm, her aesthetic sensibility inseparable from her work in terms of domestic space-making. In that, she elevated housework to the level of an (imperial) artistic enterprise, and, in turn, presented art as an (imperial) domestic act.

The art of minor architecture on the settler frontier in British Columbia was therefore the art of making and remaking the home according to prescribed rules coupled with the art of representing oneself in the act of making. This production of home space in the Pacific northeast in the ‘Age of Empire’ involved translating colonial understandings about interiority and exteriority, sites and objects, into a domestic spatial logic. In the process of physical and symbolic production, the three women discussed in this essay each negotiated their identities as both aesthetic and productive subjects. In contrast to the architecture of their male counterparts, as well as the broader imperial realm, the minor architecture produced by women did not ultimately exist in any finished form, since it was about labour itself – that is, the labour of making, maintaining, rearranging, re-matching, and so on. The power of architecture in this register was both to tie female identity to labour qua labour and also to refract imperial spatial categories within the physical micro-geographies of the intimate and everyday spaces of white settlers’ homes.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Hampton Fund New Faculty Grant administered by the University of British Columbia.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.