Green imaginaries: spatial explorations into socio-ecological processes

The historical geographical process that started with industrialization and urbanization and aimed at taming and controlling nature through technology, human labour, and capital investment. The same process aspired to rendering modern cities autonomous and independent from nature’s whims. This project transformed socio-natural landscapes across the world and disrupted the pre-existing ontological categories of ‘nature’ and ‘the city’. [1: p. 36]

The current state of the planet, where the degradation of the world’s ecosystems and the number of natural disasters, rising sea levels, water shortage, pollution, and dependency on finite natural resources are escalating at an increasing pace, clearly illustrates the problems that the rapid urbanisation of the twentieth century and its related extraction of resources have caused. This situation urgently calls for radical questioning and rethinking of our current models of urban and rural development [2; 3; 4; 5].

The history of modern Western urban planning and design exhibits a strong dichotomy between the notions of nature and city [1; 6]. This dichotomy, where nature is perceived as something separate from human culture is still prevalently dominant in Western urban planning and very visible in the design of contemporary built environments. Crucial in this context is the fact that how we as urban planners and designers perceive and relate to the notion of nature preconditions how we transform the environment through the process of urbanisation [7]. Whether it is manifested in approaching nature as a threat that needs to be controlled [8] by building technological infrastructure projects to protect us from changing environmental conditions such as floods, or that nature is something that needs to be protected and preserved from human intervention, this dichotomy creates a conflict between nature and culture in the practice of urban planning and design. Even the notion of nature as something that can provide us with ecosystem services to sustain our way of life [9] – looking at nature as a resource that we can use for our benefit – is still based on the idea of the nature-culture divide.

The strong presence of this dichotomy in the practice of urban planning and design impacts the ways we imagine how we inhabit earth. Therefore, we argue, to change how we plan, build, and live our lives in a long-term sustainable way, a crucial challenge for urban planners and designers is to explore alternative ways of relating to nature, beyond the conventional ways of perceiving nature as something separate from society.

In their article ‘Radical urban political-ecological imaginaries: Planetary urbanization and politicizing nature’ [7], Maria Kaika and Erik Swyngedouw ask for a radical shift in how we understand the current situation and how we could imagine a different future by looking into what visions of nature and what socio-environmental relations are being promoted in today’s society. Here alternative ways of seeing and understanding the relationship between nature and culture found in other fields of knowledge, such as political ecology (Latour, Kaika and Swyngedouw), ecocriticism (Morton), and ecosophy (Guattari) are useful. Taking its point of departure in questioning the role of the relationship between nature and culture in urban planning and design, this research is looking into alternative ways of relating to nature beyond the conventional ways of perceiving nature as something separate from culture.

A significant argument in this debate is that the hegemonic notion of nature is an aesthetic socio-cultural construct, driven by our cultural heritage and the need to understand, relate to, and control our environment, that only exists in our consciousness [10; 11; 12; 13; 14]. Seen in this light, the contemporary notion and aesthetic vision of nature being something very different from culture in urban planning and design are some of the main obstacles to a truly forward-looking strategy for a sustainable socio-ecological future [14; 15; 16]. Since the notion of nature preconditions how we as urban planners and designers perceive, imagine and transform the environment, a questioning of the notion of nature and the relationship between nature and culture is crucial to critically discuss and achieve a real sustainable socio-ecological development in the context of urban planning and design [7].

In this text we will look at a series of spatial explorations into socio-ecological processes; design projects developed in our practice and teaching, here framed as ‘green imaginaries’, projecting new ways of seeing and imagining the future. Focusing on changing urban and landscape conditions, we map the forces and processes behind these transformations over time to project alternative future scenarios. Departing from the perspective of the relationship between nature and culture, we discuss the possibilities for alternative ways of understanding the notion of nature and the relationship between nature and culture to unlock and provide the practice of sustainable urban planning and design.

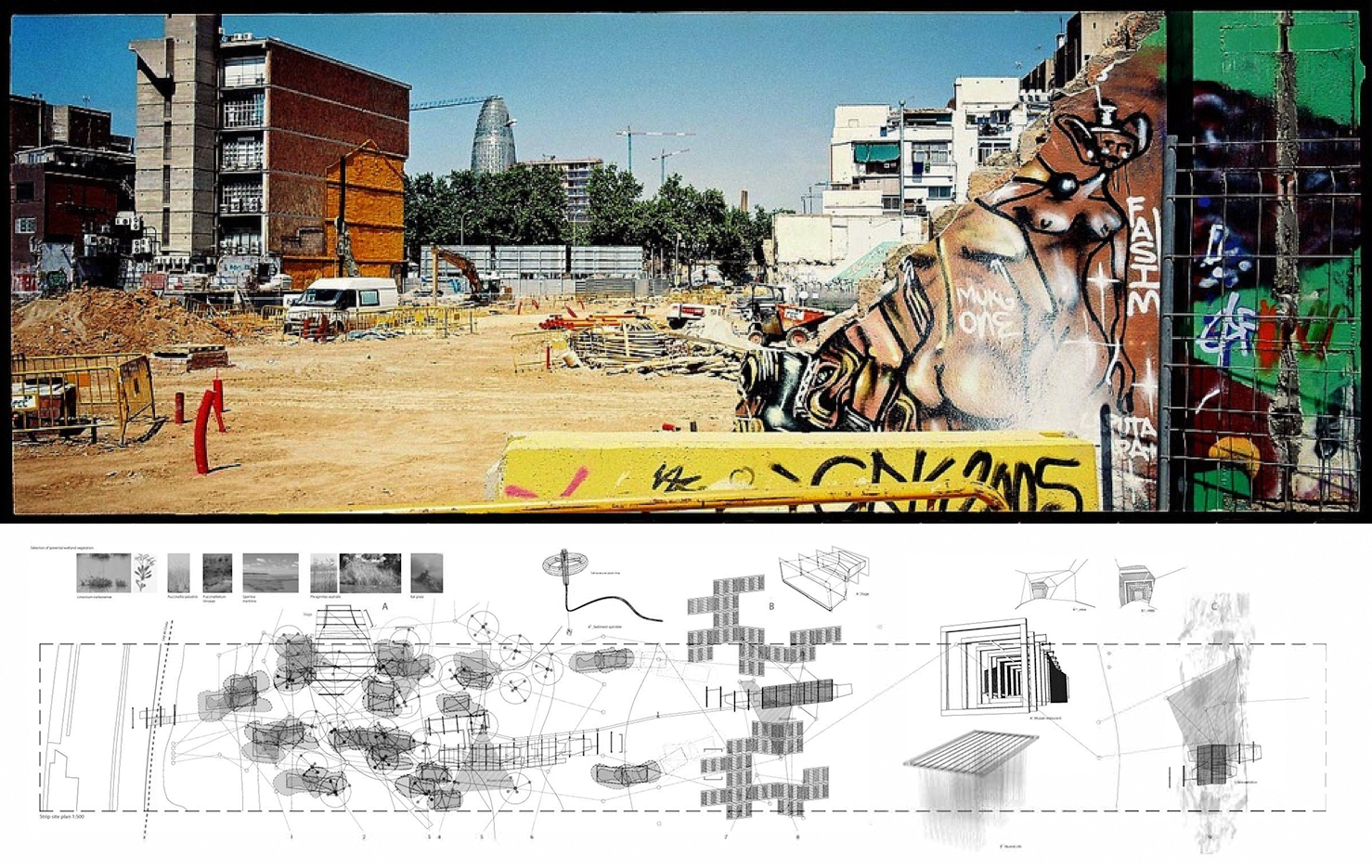

Figure 1

Coastal Erosions and Alternative Biotopes, Barcelona, Spain. (Top: Photography courtesy of Oriana Eliçabe. Bottom: Courtesy of Carl-Johan Vesterlund).

Spatial explorations into socio-ecological processes

In our professional and academic practice, we have carried out a long trajectory of spatial investigations into global and local emerging conditions to develop ways of operating and catalysing change in urban and rural areas today. Studying global socio-ecological crises in local contexts, these explorations depart from a methodology of constructing alternative scenarios and other models of development, that we have developed over many years. In this text we gather a selection of these investigations; case studies of cities and regions with changing urban and rural environmental conditions where a conventional view of what is seen as nature and culture is creating a conflict between urban development and the survival of biotopes and organic life. Our methodology is based on an approach to environmental conditions as being territorial products of historical and contemporary geo-political, socio-cultural, economic, climatic, and environmental processes [17].

The framework for developing these explorations is a series of alternative open-ended scenarios, allowing us to critically examine processes and emerging phenomena in the areas of study. The use of open-ended scenarios enables us to set up a test bed of possible outcomes, not pre-determined and rather as a model of conditions in flux, and to critically approach the design questions. Reading a city, coastal landscape, or territory as a body, an organism, an autonomous system, and a series of interdependent relationships, we use mapping and explorations on multiple scales, from planetary, global, and local scales using simultaneous overlapping time frames of the past, present, and future.

By questioning ‘Western paradigms of clock time, linear progression and positivist predictability’ [18] and ’research paradigms premised on positivist ideas of cause-effect chains and prognoses that advocate “evidence-based planning and design”, or future projection based on those things that can be known through measurement and aggregation’ [19: p. 276], we approach the notion of the future as a charged space with political dimensions into the future.

To understand emerging conditions and overlapping patterns, we attempt to combine various cross-disciplinary perspectives to critically expand ways of seeing, imaging, and acting. Mixing and combining ways of visualising, using interactive models and prototypes, allows us to investigate, represent and consider emerging phenomena and conditions, social and cultural practices, global and local actors, agents, biological and geological dimensions, and socio-ecological events. We seek to describe dynamic overlapping conditions, spaces in flux, biophysical properties, and tangible and intangible dimensions [20].

Through this perspective, using different ways of exploring emergent conditions, as a framework for projecting future scenarios, and imaginaries that are both transformative and generative, we have tried to read these environments as dynamic entities with multiple possible futures. Departing from James Corner’s [21] formulation on perceiving landscapes not as terra firma, but as terra fluxus, where spatial form is a ‘provisional state of matter on its way to becoming something else’ [21: p. 311], and inspiration from the notion of ‘urban metabolism’ where the city is the result of its metabolic processes [22; 23; 24], we explore the changing conditions of these urban and rural environments over time. Without making a distinction between natural and human forces, we explore the flows of displacement of organic and mineral material as well as changes in the circulations of energy and matter in ecosystem cycles, analysing the physical and socio-ecological effects of these processes over time. Focussing on their current and future challenges and opportunities of the situation by analysing the socio-ecological forces involved in these transformations able to identify a series of socio-ecological processes that could be drivers in an alternative development of the future of these urban and rural environments.

Our way of envisioning these socio-ecological future scenarios finds support in theories developed in political ecology, ecocriticism, and ecosophy, based on an understanding of nature as a process of co-production by organisms and environment including human involvement and agency. Here the notions of ‘landscape imaginary’ [25] and ‘projective ecologies’ [26] are important references for our way of developing alternative visions departing from the current situation and its conditions. Aligned with the thinking of Gregory Bateson [27] and Félix Guattari [28] we believe in expanding the notion of ecology to include social relations and human subjectivity as a model of the world and the medium to imagine and project other ways of living and coexisting. Ecology could here be understood as a medium of thought, exchange, and representation, as well as the agency of design in shaping that world to project a range of better futures [29]. We coin these future scenarios ‘green imaginaries’, exploring possible socio-ecological relations, and how the relationship between nature and culture could be conceived differently, developing transformative projective imaginaries that enable a generative way of working.

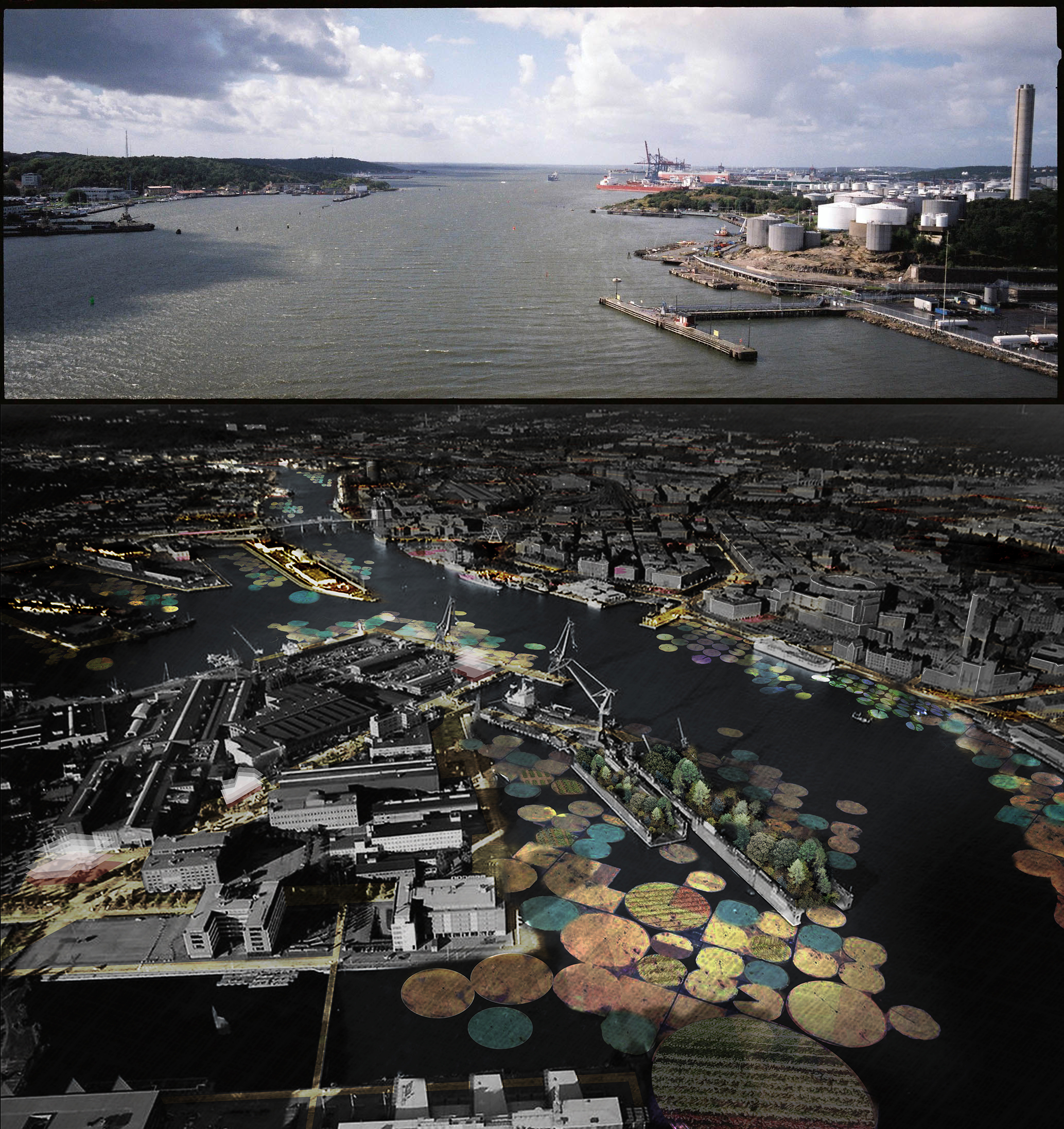

Figure 2

Fluctuations, Flooding and Water Ecologies, Gothenburg, Sweden. (Top: Photograph courtesy of Oriana Eliçabe. Bottom: Courtesy of U+A Agency (Ana Betancour + Carl-Johan Vesterlund) with Mathias Holmberg).

Green imaginaries

This exploration into socio-ecological processes and green imaginaries starts by looking at coastal erosion, here illustrated through a case study of the shoreline of Barcelona. The urbanisation of the Barcelona waterfront, as part of the regeneration project for the 1992 Olympic Games, radically transformed the existing coastal ecosystem through a series of concrete architectural interventions. The coastal landscape, already previous to this urban intervention heavily suffering from beach erosion due to the transformation of the adjacent River Besós, where its natural riverbeds were turned into concrete levees to control and prevent flooding cutting off its flows of sediments previously nourishing the shoreline. In its current state, the beaches of the shoreline are regularly eroded, leaving them dependent on a continuous process of artificial nourishment of sand, a human-driven project to recreate and maintain the image of the previously lost beach landscape. The sand extracted from beaches further up the coast is continuously washed away by storms and the coastal erosion is enhanced by concrete architectural interventions.

Approaching the coastline as a socio-ecological product of direct and indirect effects of human-driven transformations these future scenarios for the shoreline of Barcelona explore generative interventions to counteract processes of erosion. These transformative imaginaries seek to construct both ecological processes of retention of the existing sediments, as well as increasing the sedimentation through productive new ecosystems changing the socio-cultural relationship between the city and the sea. Instead of recreating the landscape that existed before the transformation and erosion, we see the potential of intertwining the flows of the city and the coastal ecosystems in an alternative urban biotope, consisting of a series of wetlands and mussel and oyster farms designed as adaptive and soft architectural interventions. The creation of a diverse span of fresh/brackish/saltwater biotopes, semi-artificial marine ecosystems, and public spaces, the gradual growth of the wetlands, fuelled by the increased nourishment sedimentation from the farms, is here imagined to create a dynamic zone, extending the city into the water, and the water into the city (Figure 1).

The relationship between coastal erosion and projection of alternative biotopes allowed us to imagine how to design built environments working together with growing organic elements. This exploration starts to suggest the possibilities for environments where natural processes are part of the generation of new types of urban biotopes.

Looking further into different socio-ecological coastal conditions, we examined the rising sea levels and water level changes due to flooding in the harbour of Gothenburg. Studying the short and long-term effects of flooding and rising sea levels due to climate change, and how these have been further enhanced by human landscape interventions we traced the harbour’s historical transformation from being a wetland turned into an infrastructure machinery optimised for shipping. The process of urbanisation of the wetland through hardened edges and non-permeable surfaces gradually reduced its capacity for flood mitigation and limited its biodiversity by reducing the possibilities for coastal edge habitats.

The fluctuating water dynamics became the point of departure for the future scenarios for the harbour of Gothenburg. These transformative imaginaries seek to develop a different way of living with the changing water levels on the city’s coastal edges. Instead of seeing the rising water as a threat, we see the potential in considering the riverbanks as a productive edge and water infrastructure system that, through semi-artificial water edge ecologies, could, by absorbing water, contribute to new ways of living, working, production and recreation. Gothenburg is here imagined as a city on water, where the fluctuating water could be considered a common resource for a productive future (Figure 2).

Imagining water ecologies departing from the relationship between the transformed harbour and flooding allowed us to approach the harbour as a fluctuating water landscape where the aquatic ecosystem is an active part of the city. This exploration points towards the potential of cities that lives together with and profits from changing environmental conditions.

To further explore how socio-ecological processes transform environments on a territorial scale, we investigated the phenomenon of extractions and migrations, here illustrated through a case study in Norrland, the northern region of Sweden. Studying the effects of monocultural farming of timber, mining of minerals, and harvesting of energy through the construction of river dams, we studied changing local biotopes, decreasing biodiversity, and endangered species dependent on migration for reproduction. Looking into these processes as generators of socio-ecological conflicts, we studied their effects on indigenous Sápmi communities and their reindeer herding dependent on seasonal migrations understanding it as a patchwork landscape mirroring the control and needs of the market economy in terms of deforestation, changing water levels in rivers and dams and expansion of mines.

Approaching the Norrland territory as a landscape produced by the processes of extraction and migrations of mineral resources, energy, and biological material, we were seeking to project a socio-ecological future based on the strengthening and linking of the existing initiatives, focussing on farming and increased biodiversity. In these transformative imaginaries supporting local institutions, actors, and agents, we see the potential of using the sterile environments that the extractive infrastructural projects inadvertently have created as an opportunity to introduce farming strategies that could profit from the artificially made conditions, such as fish farming and agroforestry, creating the nourishing conditions for local, actors, organisms and biotopes to flourish (Figure 3).

The relationship between extractions, migrations, and projection of embedded habitats allowed us to imagine a new spatial organisation of these environments on a territorial scale, consisting of a system of coexisting supporting networks physically and virtually interconnecting productive places, actors, and agents with related emergent conditions.

Figure 3

Extractions, Migrations and Embedded Habitats, Norrland, Sweden. (Top: Photograph courtesy of Han Sungpil. Bottom: Courtesy of U+A Agency (Ana Betancour + Carl-Johan Vesterlund)).

Projecting alternative futures

Our approach to the dichotomy of nature and culture in urban planning and design is based on two main insights: culture not being different from nature, and the planet being a result of continuous, ongoing evolution, a process in which inert objects of the environment, humans, and other organisms constitute equal parts. Considering humans as any other organism on earth involved in the generation of the environment, we argue in line with Latour [16; 30; 31; 32], that what we should perceive as nature or environment, is co-produced by all these agents.

We argue that to be able to confront the massive environmental challenges of today and to imagine and make a radical socio-ecological change, a new radical science-based, theoretical and ecological view, beyond the conventional understanding of sustainability and the social construct of the notion of nature, is needed in the practice of urban planning and design; an understanding of ecology without nature, removed from the image of nature as an environment opposite to culture [14].

The green imaginaries we have developed, are projections of speculative alternatives based on research by design and critical reflections. Exploring how the relationship between nature and culture could be conceived differently, the research explores future scenarios by understanding environments as the result of processes of co-production by both organisms and environments, beyond a distinction between ‘natural’ and ’human’ forces [16; 30; 31; 32].

The goal is, according to Latour, to identify where we can insert ourselves ‘within lineages that will manage to last’ [16: p. 4]. Central in our thinking in our role as urban planners and designers is therefore a constant questioning of through what perspectives we understand the environment that we are living in, what kind of life we imagine, and for whom.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.