Architecture on the couch

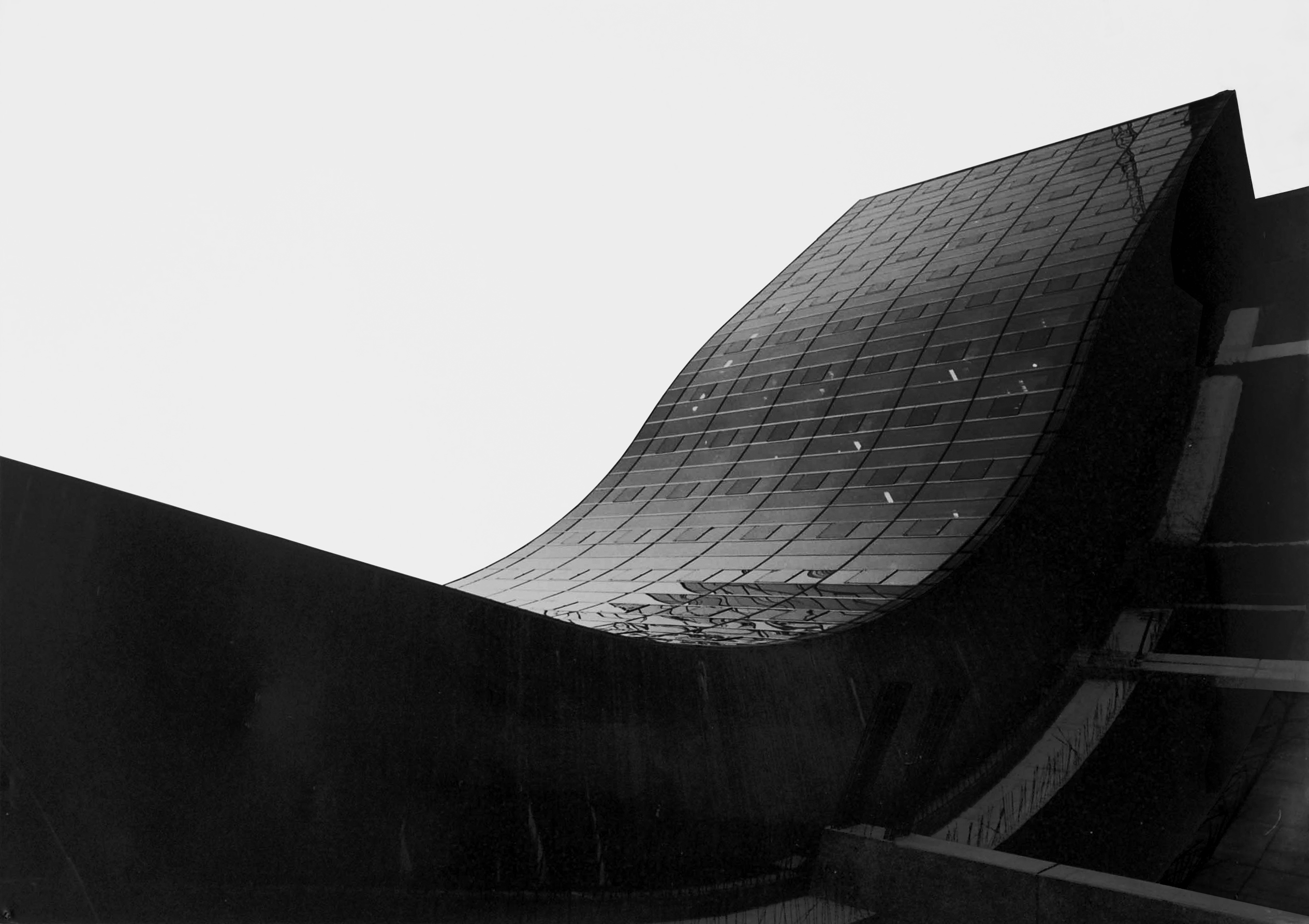

We … take vivid structures into our dreams and the unconscious that operates in the material realm of the built and the unconscious that organises each self, meet. [1: p. 36] (Figure 1)

This essay puts forward a way of thinking about architecture that enables architecture to become a psychological subject which can then be explored using a method-set developed by us to generate psychological profiling of the subject building. The essay will propose that by understanding the psychology of a building, its lifespan, utility, and effect on inhabitants may be enhanced. This has profound ecological impacts on minimising the obsolescence and consumption of the building stock, promoting the sustained use of architecture, and improving the wellbeing of its occupants. Recalibrating our relationship with architecture, the essay argues for a deeper understanding of our entwined existence with buildings. Forming a radical ecological agenda for thinking about the built environment, the contention is that architectural practice should be less about delivering newly built structures, and more about the creation and ongoing management of the psychological relational dynamics within existing architecture.

Recent investigations of intersections between architecture and psychoanalysis [2; 3; 4] and before this, its political unconscious [5], have developed some fascinating readings and exploratory works of image and text relating to existing architecture. Our innovation within this field is to see architecture itself as a psychological and social subject, capable of encompassing conscious and unconscious dimensions. Both postmodern theory and psychoanalytic understandings see the self as non-unitary and composed of different and contradictory parts. The tensions and relationships between different aspects of the self are also entangled with external milieus, partaking of both conscious and unconscious dimensions. So, the subjectivity of the individual and of architecture are both multiple in their construction. This is exactly where the psychological and the architectural intersect, creating the opportunity to redirect practice-based psycho-social, psychoanalytic, and conceptual art examinations of the unconscious and put architecture ‘on the couch’.

Figure 1

Le Siège du Parti Communiste Français (French Communist Party headquarters, or PCF headquarters), détourned and dreaming (Photograph by Michel Moch, détournement © Warren and Mosley, 2023: Courtesy of Societe Immobiliere du Carrefour Chateaudun, hereafter SICC).

This way of thinking about architecture is formed by three conceptual moves. The first is the conception that architecture is an assemblage of which we are a part. Drawing on assemblage theory, architecture is considered an entangled amalgamation of built elements, bodies, objects, systems, materiality, and immateriality [6: p. 409]. As an assemblage, it is possible to conceive architecture as having a subjectivity partaking of human and non-human qualities. The second is the understanding that, within this entangled assemblage, the relations between these human and non-human entities have the potential to be mutually affective. Architecture is understood to have capacities to express, affect, and be affected by wider social, cultural, political and individual influences, not only through conscious design but also through unconscious effects. And the third is the ability of the assemblage to have conscious and unconscious qualities that may be accessed by psychoanalytic, psycho-social, and conceptual art techniques. This necessitates the notion of the unconscious transcending the more limited individual subjectivity of psychoanalytic thinking. This notion has previously been developed and deployed in psycho-social studies [7; 8; 9; 10], itself a transdisciplinary and emergent field, but has not yet been applied to architecture as such.

These conceptual moves then enabled us as the researchers to devise a method-set composed of psycho-socially adapted social sciences methods, innovative psycho-social visual methods, psychotherapy, and conceptual art practices. The methods can be used in different combinations and the resultant data triangulated to offset the potential subjectivity bias of interpretive hermeneutics. Once identified, this method-set needed testing, which was done through a case study provided by the French Communist Party (PCF) headquarters in Paris, as designed by the Brazilian architect, Oscar Niemeyer. This building was chosen for several reasons: it is an iconic political building designed by a significant architect; it is a building with a troubled history, from its commissioning and coming into being to its mixed usage over time; and two of the authors have been for a while artist-researchers in residence in the building, giving them prior knowledge and access to resources.

The findings from this case study generated a psychological profiling of Niemeyer’s architecture. The investigators discovered hauntings, tensions, and identity issues through their research, which are briefly outlined in the third section below. The essay concludes with some consideration of therapeutic measures that potentially could enhance the psychology of the architectural assemblage.

The result of this work has different applications and outcomes: it offers a methodology for academic research, based on an expanded understanding of what a building is and can do, it offers tools for participatory research and consultancy, it can be used to think about architectural practice processes and scopes of concern, and it can influence architectural design itself, exploring how to improve a building for its users or extend its life. In other words, its innovation consists of its conceptual transdisciplinary and research/practice-based intersection that lends itself to both academic rigour and depth as well as practical application.

We are architecture (entanglement and ecology)

We are architecture. We are entwined with our buildings. We mutually affect one another. We are mutually dependent. We are entangled with our enclosures. Our emotions, our memories, our health, our functioning, and our interactions are all informed by the buildings that surround us; and we create and re-create those architectural spaces daily, through our inhabitation, our perceptions, and our actions.

We are architecture: this statement seems simultaneously simple and nonsensical. However, we put forward this statement as a foundation for constructing new terms of engagement between humans and buildings in the context of the current climate catastrophe. Doug Jackson writes: ‘Instead of being distinct from the environment, we are fundamentally entangled with it – and the lack of objectivity that this entanglement implies means that the way out of this predicament [climate emergency] cannot only be through measurement and calculation but must also come from the speculation and invention of alternative forms of engagement’ [11: p. 139]. So, it is proposed that ‘we’, the grouping typically reserved for reference to humankind, are not separable from architecture, perceived as typically constituted from built matter. If we are entangled with our environment, we can be considered part of that environment. We are no longer sovereign, just as architecture is no longer just autonomous material. We are entwined. This conception holds the potential for alternative forms of engagement: an approach to architecture as the design and practice of complex inter-relationships; the consideration of architecture not as built objects, but as amalgamations of multiple entities; the sustaining of architecture, therefore, being irreducibly enmeshed with sustaining ourselves.

This conceptualisation resonates with Timothy Morton’s understanding of ecological thought as ‘the thinking of interconnectedness’ [12]. Morton uses the concept of a ‘mesh’ to refer to the interdependence and interconnectedness of all living and non-living things. The ecological dimension of this thinking is focused on the interrelationships between different entities rather than purely on the entities themselves. This privileges consideration of the impacts that entities have upon one another and lays the ground to assess ecological affects created through complex multifarious relations between humans and non-humans. Jane Bennett also recognises the profound ecological significance in considering the dynamics and ‘voices’ of non-human entities and contends that by ‘experiencing the relationship between persons and other materialities more horizontally’, we develop a greater ‘ecological sensibility’ [13: p. 10].

For Morton and Bennett, alongside other New Materialist, Speculative Realist and entanglement thinkers (Manuel De Landa, Graham Harman, Iain Hamilton Grant, Karen Barad, and others) the focus on interrelationships and interdependencies between entities, human and non-human, animate and inanimate is the basis for understanding situations from beyond the human-centric perspective. If we apply this approach to architecture, it raises questions about where the extent of the ‘architecture’ begins and ends (Figure 2). If humans form a part of architecture, so may objects within a building, systems of communication, supply and waste, organic and inorganic matter held within or on the surfaces of built structures, and other living inhabitants such as pigeons, rats, insects, etc. The humans might include those that brought the building into being, those who work in the building, and those that visit or dream about the building. The ‘we’ within ‘we are architecture’ should be considered ecologically as a beyond-human collective.

Architecture as an assemblage

By thinking about architecture as this complex amalgamation of entities, there are a host of resulting impacts of those relations that have ecological consequences at many scales. To grapple with this dynamic amalgamation, our second assertion is that architecture is an assemblage. Developing from Gilles Deleuze’s relational concept [14], Manuel DeLanda offers a valuable approach to the consideration of the dynamics within an assemblage [15]. DeLanda most often applied his assemblage theory to social groupings and organisations; here we are tuning it to an architectural subject. DeLanda contends that an assemblage has emergent properties that are produced by the interaction between the parts. The parts exhibit capacities that are unique to those interactions, but that ultimately the assemblage is decomposable, the parts being detachable or replaceable without losing their inherent properties. We propose that architecture too, as an assemblage, has emergent properties that are a result of the interactions between occupants, other stakeholders, built elements, systems, and objects. These entities develop capacities about each other, such as well-being or sickness, utility or obsolescence, affection, or repulsion. The architectural assemblage can be reconfigured with potentially new resulting emergent properties overall if specific entities are altered or substituted to improve wellbeing and utility.

When we practice architecture, we create and recreate the internal relational dynamics of the architectural assemblage. A design decision can affect the emotion of an occupier, the microecology of plants within a gutter, the sense of ownership of a building by the city’s citizens, and the movement of material resources around the globe. The assemblage is plural and interconnected and so its effects ripple through ecologies at different scales. Focusing on the scale of the building, the first significant consequence is that of health and wellbeing of occupants and other stakeholders. The second is the response of the assemblage to shifting aspirations and social/cultural/economic/political forces. Depending on the response, these forces may generate redundancy and replacement of the architecture with enormous expenditure of materials and energy, or the sustaining of the building and possible enhancement of its utility with less use of resources. To sustain architecture, its assemblage has to mutate. In order that we understand how the assemblage should mutate through design, repurposing, built intervention, modes of occupation, or just ways of thinking, we must firstly understand its relational dynamics through time.

However, these relational dynamics are complex and subtle. They are in part formulated by emotional responses, conscious thoughts, and unconscious associations. To investigate the relations within the architectural assemblage, we argue that it is necessary to explore how entities affect each other and how affect relates to psychology.

Figure 2

Partial view of Le Siège (PCF headquarters) from a bar in Place Colonel Fabien, Paris (Photograph by Sophie Warren and Jonathan Mosley: Courtesy of SICC).

Affect and the unconscious

In their power to affect, buildings possess a kind of agency that might want to make us get away from them, demolish, or restore them. Lisa Blackman cites Patricia Ticineto Clough when discussing the way that ‘affect participates at every level and scale of matter, from the subatomic to the cultural, such that matter itself is affective’ [16: p. 5]. Affect theory dissolves the distinctions between organic and inorganic, living and not living, but, importantly, it is also about movement, change, becoming, and transformations, most often occurring out of sight, yet perceptible. Conceiving buildings from an affect theory perspective reverses the normal anthropocentric trajectory of much academic study, while also avoiding the objectification or excessive anthropomorphising of the non-human aspect. The research project in this essay is fundamentally psycho-social by aiming to build on this ontological foundation by using what can be derived from both a psychoanalytic and affect theory perspective pertaining to a building as both a subject and an assemblage – something that would see the assemblage itself as forming a fragmented sui generis subjectivity, but a subjectivity nonetheless.

Most importantly for this essay, affect theory allows for an exploration of conscious and unconscious levels and scales of influence in a human/nonhuman assemblage, such as a building can be conceived to be. Affect theory has foundations in the philosophy of Deleuze, Bergson, Spinoza, and Whitehead and tends to speak of affect as pre-conscious, pre-personal, and non-intentional. Deleuze himself was not reluctant to use the term ‘unconscious’ in relation to affect, yet his conceptualisation was in notable contrast with the Freudian focus on repression and Oedipal dynamics [17: p. 205]. He considered it more positive and broader in scope, less about repression than selection, signs rather than signifiers, and expression rather than representation. This does not mean that Deleuze and Guattari rejected all of psychoanalysis. Rather, they can be seen as intensely engaged with it, wishing to correct and contribute by taking psychoanalysis beyond the familial and individual internal milieus it had confined itself within. Their term, ‘schizoanalysis’ [18], is an endeavour to break down boundaries and go beneath the surface, just as psychoanalysis had very controversially been doing from its beginning [19]. Their legacy, along with that of Spinoza and Bergson, is what stands behind affect theory and its contemporary developments across many different fields of study.

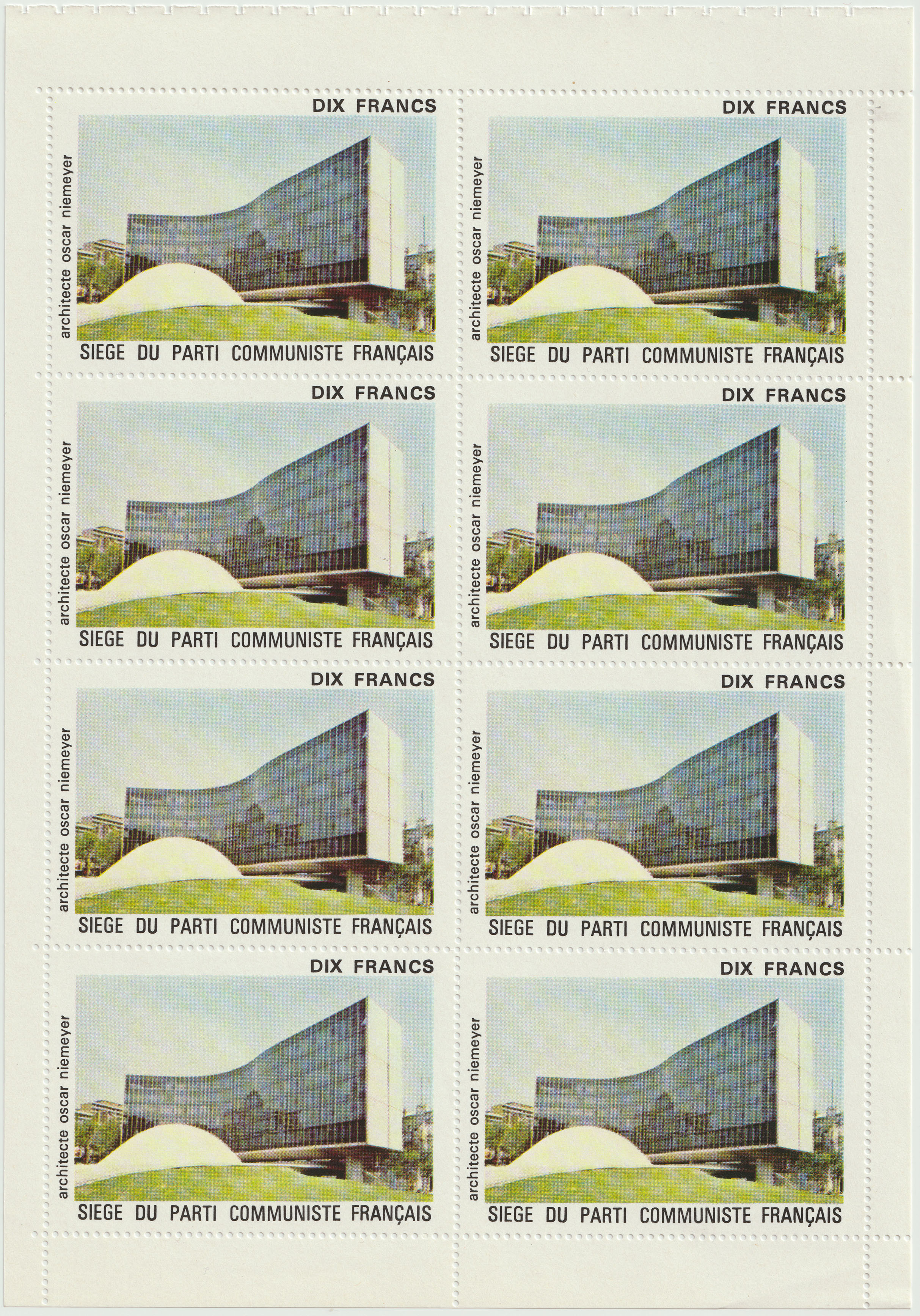

Figure 3

French Communist Party stamps given in exchange for subscriptions and donations, this edition raising funds from the membership for the second construction phase of the new headquarters (Photograph by Sophie Warren and Jonathan Mosley: Courtesy of SICC).

Conceptual framing for a psychology of buildings

To address a building as a psychological subject, our conceptual framing identifies several foundational attributes:

A building is the product and expression of a web of relationships comprising human and non-human aspects; in that sense it is relational both in the way it comes into being and in the way that it is used and related to (Figure 3).

A building is an entity of time, with a personal history of people and events. It can be said that a building is a condensed expression of time into space. Buildings have a lifespan dependent on their design, materials, and care bestowed on them to delay the ravages of time.

A building speaks through its body and its language is mostly, though not exclusively, visual and spatial. It speaks through its form, its style, and its gestures, qualities of light and dark, colour, texture, and temperature, and qualities of materials where touch and smell play a part too. These are experienced by the passer-by or occupant both in a dwelling or moving through, or past the architecture.

A building is subject to power and has power to affect. Humans have power over buildings in their design, use, and maintenance, but humans are also affected by the building itself, its ease of use, and its ambience or atmosphere which are all able to influence people’s wellbeing and productivity.

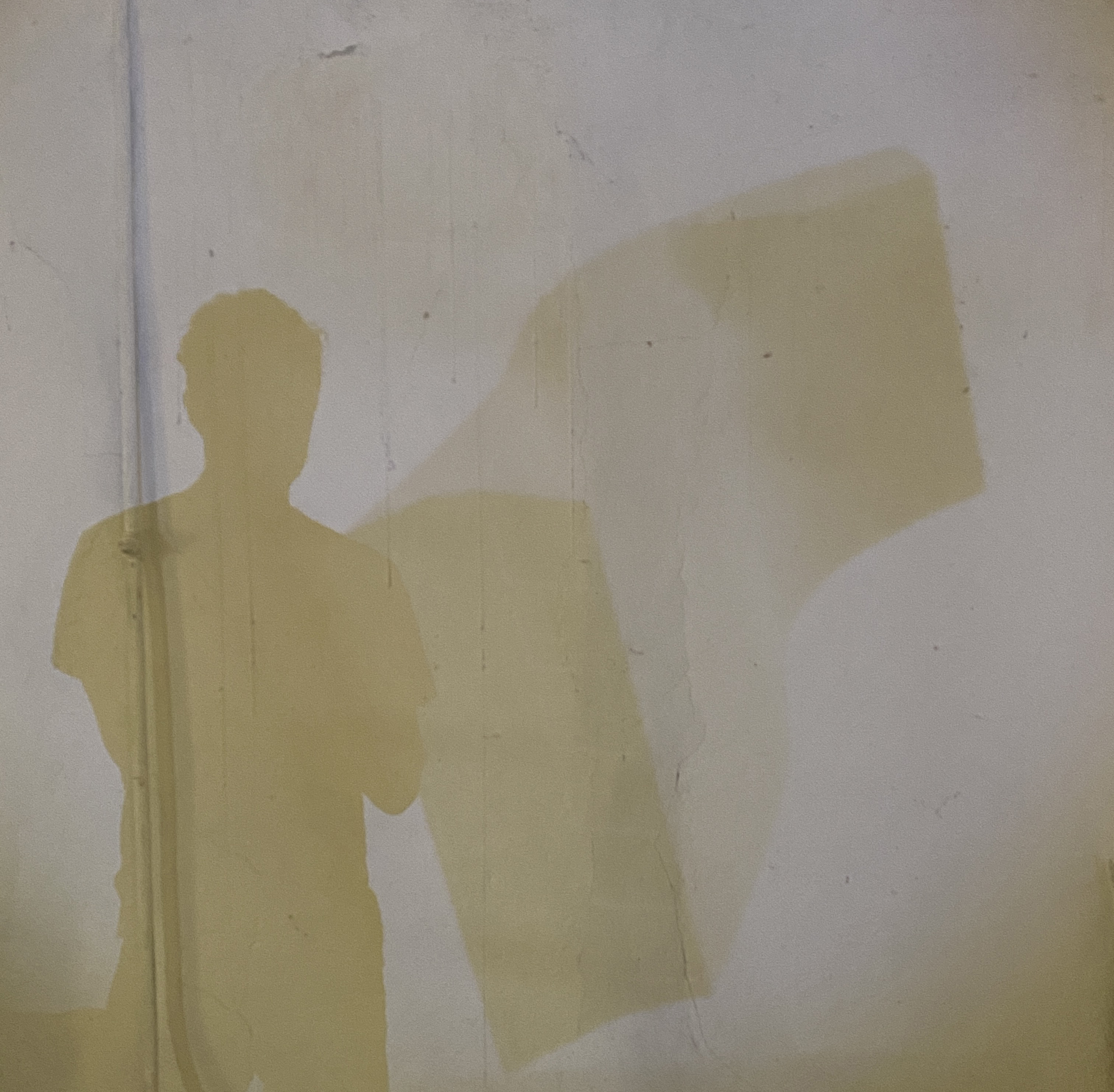

And finally, in the sense that a building has unconscious qualities because there are impacts of unconscious decisions embedded in the design and management of the architecture, impacts of unconscious relational attachments of the building’s community to the architecture, and because of the building’s ability to affect the unconscious of the occupant (Figure 4).

Insofar as they are conceived, built, furnished, and inhabited by humans, buildings partake of human-endowed qualities – and insofar as they are non-human, buildings partake of qualities that human materiality cannot afford us. The non-human endowed qualities of architecture include hardness and durability that transcend the single human lifespan; shelter from the elements and protection from animals and some other humans; elements of adornment external to the human body, as much as clothing or jewellery may offer, whether minimalist or maximalist in style. Human-endowed qualities of architecture include expressiveness, character, and gesture expressed through form, which may include contradictions and paradoxes. These are inscribed through rational as well as unconscious choices, accidents, and unforeseen events. What is expressed in final form can be read as signs, in a Deleuzian sense [20], of underlying virtual conditions. Blind spots that may or may not be thought of as just mistakes, may tell of unconscious processes of denial or narcissistic aspects, or of traces of traumatic events, unresolved conflicts, or losses, which may even be thought of as hauntings in some cases. From this conceptual framing, our theoretical basis is established and creates the potential for the development of methods and their operationalisation to explore the psychological architectural subject.

Figure 4

Partial view of Salle de délégation (Delegation Room) on the second underground level of the PCF headquarters (Photograph by Sophie Warren and Jonathan Mosley: Courtesy of SICC).

A method-set for action

This research project began with a series of transdisciplinary dialogues centred on the key problem of how to conceptualise and research the psychological dimensions of buildings. The researchers started to identify ways of thinking drawn from our different knowledge basis and perspectives. To put it in Deleuzian terms, the logic of this way of working is nomadic [20], and so is not about territorial (theoretical or disciplinary) boundaries, but about intersecting tracks, paths that can converge and diverge, with each offering some useful harvest of food for thought. Our early dialogues followed an inductive process whereby a conceptual framework and methodological approach were generated to address the problem. Thus, the subsequent methodological approach emerged through conceptual art thinking that intentionally misused, shifted, and questioned subjects as a creative and exploratory process. The methodology re-purposed and re-directed existing methods from specific disciplines towards the assemblage of architecture as a psychological subject. For example, psycho-dynamic therapy from the field of psychoanalysis would be reconfigured to focus on an architectural (as human/non-human collective entity) rather than on the sovereign human subject.

Within this methodological approach, we were concerned with developing methods that could address the entanglement of human and non-human aspects, but only in so far as they pertain to a building itself. This included aspects from its locational history and the history of those who commissioned it and those who used it, through to its aesthetic and material qualities and the changes of usage over its lifespan. All these aspects were seen to contribute to a building’s subjectivity. This genealogical approach was deployed on the basis that both conscious and unconscious factors about traces from the past may be identified as having found expression in the final form, affective qualities, problems, and uses of the building over time. These expressions in turn could create an affective environment that resonates at mostly unconscious levels even for those visiting, but more strongly for those people inhabiting or operating within a building (Figure 5). The set of methods was hence developed with the ability to capture these aspects and engage with the perceptions of multiple protagonists within the communities of the building, from designers to users to passers-by. The method-set includes:

Figure 5

A still image from ‘Uprising’ (2016), documenting an action within the PCF headquarters that explores the politics of motion, as an example of using the ‘Days of Action’ method (© Warren and Mosley: Courtesy of SICC).

Family tree and events timeline (generating a speculative image/text genealogical diagram with an accompanying timeline of relevant events). This method is based on humanities (architectural/social/political/historical) research into secondary sources, including building/organisation archive materials where available, and social science-based stakeholder interviews. This creates a basis of knowledge upon which its speculative dimension is developed as a set of ‘family’ relations.

Psycho-dynamic therapy (psychoanalysis of one or more people standing in for the building with a therapist). This is based upon psychoanalytical and psychodynamic therapy practice, adapted for an architectural subject.

Deputised Object (interpretative physical/virtual objects that embody the psychological presence of the building for interaction with study participants). These objects are generated using creative practice-based research techniques by which forms are produced to express psychological ideas about architectural subjects, and can be employed within therapy situations for physical interaction.

Visual Matrix (psycho-social method attuned to architectural subject involving participants either from the building’s community or not). The matrix includes facilitated small group free-association techniques based upon images, then followed by reflection.

Social Dreaming (psycho-social method attuned to architectural subject involving participants either from the building’s community or not). This includes facilitated small group free-association techniques based upon dreams, then followed by reflection.

Days of Action (individual and collective actions within the building). This creative practice-based method has a basis in participatory action research and performance art whereby new knowledge and understanding may be generated from responsive situated behaviour followed by reflective analysis (Figure 6).

Figure 6

A moving image sequence from ‘Revolution’ (2016), documenting spinning down a corridor at the PCF headquarters to a soundtrack of Louis Aragon’s ‘Art of the Party’ speech from the 1954 PCF congress, as another example of the ‘Days of Action’ method. https://vimeo.com/312577319 (© Warren and Mosley: Courtesy of SICC).

The method-set is thus able to be applied to a case study and operationalised in a customised manner according to the conditions of the case, the scope of the research project, and the degree of access to the architecture and potential participants – in other words, different methods can be used in different combinations and sequences. A case-study approach allows for the specific focus to offer containment and provides a point of anchorage to depart from and return to. Case studies are therefore a method of research commonly used in psychoanalysis and many of the social sciences [21]; [22]; [23]; [24]; [25]; [26]. Using a case study can be simply a holistic way of delineating the boundary of an entity, in anthropology or sociology, or of a person in psychoanalysis.

To apply our method-set, Niemeyer’s French Communist Party (PCF) headquarters in Paris, constructed between 1968 and 1980, was chosen as the first case study for the reasons mentioned before. The building has a complex identity, being known as ‘La Maison’ to many of the comrades, or else as ‘Le Siège’, meaning headquarters, it also is marketed as ‘Espace Niemeyer’ and as such used as a location for fashion shoots, music videos and films. Two of our research team, Sophie Warren and Jonathan Mosley, had the advantage of being artists/researchers in residence in this building for three months. This immersion within the life of the building enabled the testing of methods on experiences and data gathered, including oral interviews, visual ethnographic records and documented actions [27]. Within the research team, our roles were thus allocated to allow certain members to engage in multiple methods while others just focused on one method, so that the experiences and findings from one method of testing did not contaminate the next method. This then assisted the triangulation of findings between the different methods [28].

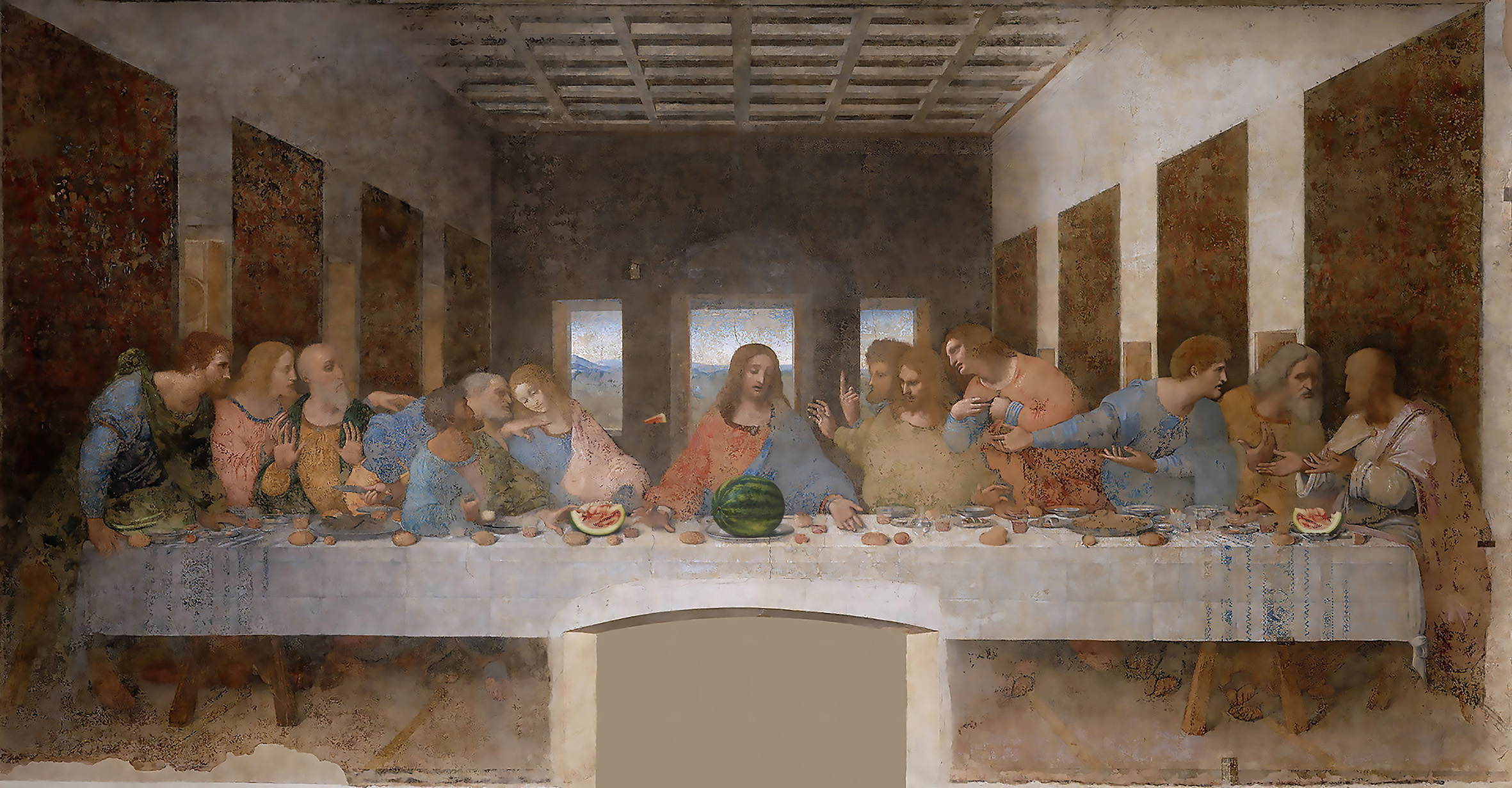

Figure 7

‘Devouring da Vinci’ (2023), a détournement of Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Last Supper’ masterpiece to embody a slight tropicalisation of European culture, thereby exploring the Brazilian Antropofago approach of cultural cannibalism – this collage is part of the PCF headquarters family tree (Painting image is freely available from Wikipedia Creative Commons, détournement © Warren and Mosley, 2023).

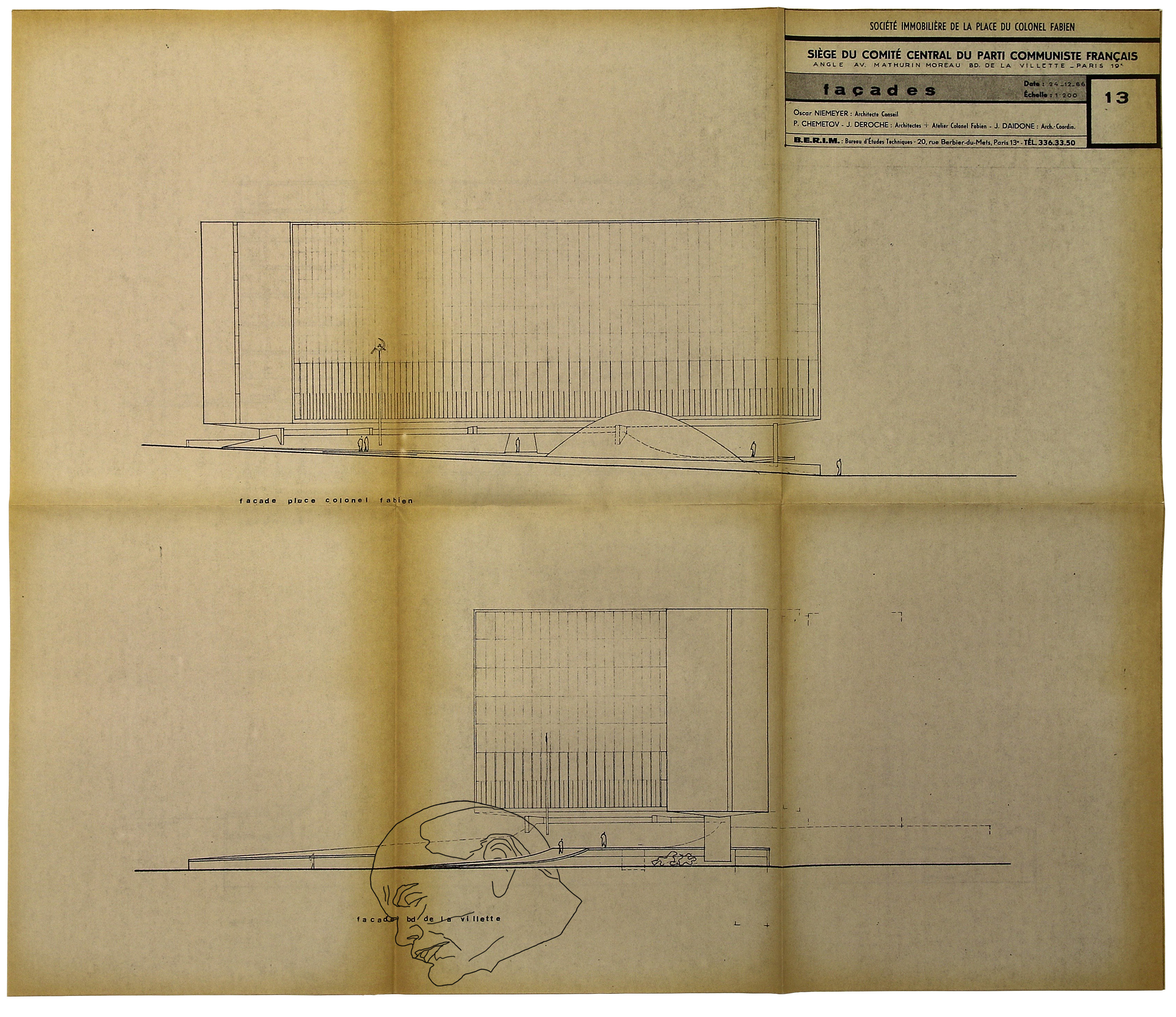

From the method-set discussed above, four of them were deployed in sequence and then thematically analysed. In terms of the first, which is the Family Tree and Event Line, this genealogical approach entailed creating a ‘family tree’ for the building alongside an event line specific to this human/non-human architectural assemblage. Together these mapped the web of significant influences and relationships, from the history and choice of site to the choice of architect, design process, construction, building uses, events, and cultural/societal shifts up to 2020. For example, in the family tree the Baroque Modernism of the PCF headquarters was seen as having a lineage back to the inter-war Brazilian ‘Antropafago’ movement, which had referenced the cannibalistic Tupi tribe in devouring European culture to produce a new Brazilian culture [29] (Figure 7), as well as to those Surrealists in Paris who were connected to the French Communist Party. Although speculative in terms of creating a ‘family’, the entities and relations of this family tree were based on multiple interviews, including with the project architect Jean DeRoche, and extensive desktop research within the PCF’s archives. By including people, buildings, landscapes, books, artworks (Figure 8), manifestos, finance and multiple identities, the family tree visually and conceptually embodies an entangled, explicitly interconnected assemblage, structured into temporal and thematic strands. This family tree and accompanying textual event line is an example of creative practice-based research output generated through collaboration with the artist-researchers in the team.

Figure 8

‘Looking for Lenin’ (2023), a détournement of a design drawing for the PCF Headquarters, exploring the unconscious ‘Cult of Personality’ within the architectural scheme – this collage is part of the PCF headquarters family tree (Image by original architects, détournement © Warren and Mosley, 2023: Courtesy of SICC).

The above stage also acted as a preparatory tool for the second kind of research method, that of Psychodynamic Therapy, a technique that is aimed at putting the architecture ‘on the couch’. For that purpose, we tested the possibility that a stand-in for the building could be part of a series of psychotherapeutic sessions to unearth unconscious aspects of the building’s subjectivity. This stand-in role was taken up separately by the two investigators with knowledge of the building, and the psychotherapy sessions were conducted by an experienced therapist who is active academically in the field of psycho-social studies, and who had been purposely kept away from working on the family tree and event timeline. This allowed triangulation of both the feasibility of working with a psychotherapeutic process and not to prefigure ‘unthought knowns’ [30] or other unconscious aspects that emerged in the therapy.

The key innovation in this method is the adaptation of psychodynamic therapy to an architectural subject as the ‘client’ through the use of a human stand-in (the qualification for the latter role being one or more people who know the building well). In other such interventions, this could well be the designer, a building manager, a researcher experiencing the building, a user, or a small group of the these. In this case study, the use of therapeutic conversation and consultation allowed an exploration of the building’s subjectivity, including how a building has a history as well as a present pattern of use which can be a guide to future potential and action. A range of issues emerged ranging from identity, genealogy, and creativity through to experiences or, more properly, characterisations of the non-human, which were typically harder to express and more enigmatic or mysterious. The human stand-ins had the advantage of being very familiar with the building, and while in it, not of it. When considered as researchers, they had both insider and outsider positions about their research subject.

The human stand-ins for the PCF headquarters, Sophie Warren and Jonathan Mosley, were offered time-limited consultations (respectively two and four sessions) which gave sufficient time for joint assessment and exploration leading to the emergence of a focus for further exploration, and some problem-solving. The therapist had no prior knowledge of the building concerned. Given the relational psychodynamic orientation of the therapist, this case study offers input from both ‘clients’ and therapists. Client 1 was a conceptual artist (female) and client 2 was an architect (male). In these sessions the gender of the building changed: this occurred between client 1 and client 2 but also sometimes in a particular context that was being elaborated independently of the client’s gender. To give a flavour of the therapy exchange between the therapist and ‘the building’ that was on the couch, the following is a short extract of the therapy ‘script’. The script is a curated and edited version amalgamating and condensing the many hours of therapy into an hour-long soundtrack, created for an exhibition. This section here picks up on the sense that the PCF headquarters is a ‘multiple or several’ entity.

PSYCHOTHERAPIST

I suppose one of the problems that comes with an experience of multiple personas or multiple selves, is the fear of madness, dissociation, cracking up … you know, not being yourself at all. Not being able to function. However, once you get into an extended sense of self, potentially you can do more if you can risk the uncertainty. So, there’s something about finding the benefits or creativity or the survival value in this kind of more multiple self.

PCF HQ

Living with an extended sense of self has been agonising so far. For many years, I denied the existence of these other personas. But their voices became stronger and more demanding and I was unsure whether they were for me, or against me. So, I thought the best thing to do, the only thing to do, was disassociate myself from them. But when Espace Niemeyer made a public appearance, I felt more exposed than I’ve ever felt. And now the truth is out there. The split within me is on display for everyone to see. Since my renaming and rebranding as Espace Niemeyer, it is as if I’ve been fighting for possession of myself … which has split and fractured over time. So, your proposition is appealing, if a little curious. You think, rather than deny who I am, or who they are, we might just be able to co-exist, if we fuse our separate personalities into one hybrid identity?

PSYCHOTHERAPIST

It’s certainly a possibility worth exploring.

PCFHQ

It might even relieve me of this unbearable tension, and all this running back and forth … in what I can only describe as a desperate search to find myself.

PSYCHOTHERAPIST

Yes, it might.

PCFHQ

As novel as it sounds though, this consolidated personality idea is a risky proposition, no? How can I be certain the others will tow the party line? Hmmm … I have to be sure I understand what we’re talking about here. I think what you’re saying is, rather than escape myself or selves, which I have been longing to do, it’s more a radical recapture of my different personas? So rather than joust and jockey for position … we will agree to host our differences and our dissensus? Is this the survival value that you are talking about?

PSYCHOTHERAPIST

Yes.

PCFHQ

So, no one voice or entity is sovereign in this multiple or consolidated self?

PSYCHOTHERAPIST

No, and the implications of it are unknown. What I mean by that is they are to be discovered.

Figure 9

‘Deputised Object’ (2023). The physical object in the PCF headquarters has a projected double to which is it linked (Photograph © Warren and Mosley, 2023).

As the third method, we developed the idea of ‘Deputised Objects’ which could act as deputies for the mute forms of the PCF headquarters. Extending Winnicott’s concept of a transitional object [31] – for example, a teddy bear that stands in for a temporarily absent parent – the Deputised Object is neither a model nor a pure artistic creation. It is a non-verbal, three-dimensional, artistic interpretation of the relationship between building psychology and the artist, creating a thirdness that belongs to both. It is in that sense a ‘both and’ object, both imagination and reality, both absence and presence, both physical and spectral, both object and relationship. It acts as an artefact of artistic production, but it is envisaged as a deputy for that relationship in the therapy setting (Figures 9, 10)."

The findings from the above processes were then triangulated to avoid ‘wild analysis’ [32]. This triangulation consisted of a fourth method, a ‘Visual Matrix’ group process, whereby images of the building were presented to a group of people familiar with psycho-social methods, but without prior knowledge of the building presented, to enable freely associative and reflective examination. The Visual Matrix is a recently devised, group-based, ‘affect rich’ method aimed at allowing unconscious aspects to emerge from free associating to images [33]. Free association is a foundational aspect of psychoanalytic work and is at the heart of several different methods used in psycho-social research and consultancy. Other aspects include Social Dreaming Matrix [34], Social Dream Drawing, Photo-Matrix [35], Role Consultation Sets [36], and the Balint method [37]. These are all group-based processes that rely heavily on the visual and the idea of emergence, which is strongly allied to affect theory. The Visual Matrix process lasts for 90 minutes and consists of two phases. Phase 1 starts with a slide show of around 15 images, after which participants are invited to share the free associations elicited by the images; Phase 2 then consists of reflection and sense-making from the materials shared in the first phase.

For our pilot, we enlisted a group of 10 participants with experience in such processes, but with no prior knowledge of the PCF headquarters. The research question for the event was: what is the unconscious of this case-study building? The Visual Matrix method was repeated in a shorter version with them as a set of participants also new to the technique. The results of the triangulation between matrices and the other methods have been uncannily similar, confirming key themes in terms of both the ‘character’ and the ‘life’ of this building arising from the multiple participants and methods. The fact that the Visual Matrix in both its long and short versions and with different participants yielded similar themes allows a degree of confidence in our research methods and the possibility of working less extensively with the other desk-based aspects.

Figure 10

‘Deputised Object’ (2023). The projection in the PCF headquarters haunts the physical object to which is it linked (Photograph/ © Warren and Mosley, 2023).

Psychological profiling

This section of the essay explores the psychological profiling of the case-study building that was generated from applying the combined methods described above. Although the profiling can be structured into specific themes, there are dynamic interrelations, overlaps, and intersections between them. The profiling provides a sample of some of the main psychological issues, hauntings, blind spots, or ‘unknown knowns’ but is by no means the totality of the findings from the research project. It follows an expressive style of writing appropriate to the transdisciplinary and speculative approach that we had developed to address the assemblage of the building as a psychological subject. Here the building is deliberately referred to by using its multiple names: PCF (Parti communiste français) headquarters, Le Siège (French for headquarters), La Maison (French for house or home), and Espace Niemeyer (the marketing term used by the PCF for hiring out the building).

The first theme identified is that of ‘Narcissism’. In other words, to what extent was the appointment of Oscar Niemeyer a reparative urge on the part of the French Communist Play to reinstate the socialist dream? To what extent were narcissistic tendencies at a cultural level at ‘play’ [38] in terms of personality cult, project scale, and the denial of economic realities? One of the signs that narcissism may have played a part is the building’s apparent denial of the downward trajectory of the PCF, who were facing significant losses in parliamentary seats during the 1968 elections, just at the time that this major building project was being initiated. This narcissism and overreach was a near repeat of history. The debt that characterised Brasilia and its proclaimed ‘failure’ [39] threatened the completion of Le Siège: indeed, the spectre of Brasilia haunted Le Siège from its inception.

The most recent appellation of the building as Espace Niemeyer likewise displays a narcissism characterised by a lack of empathy for Le Siège in its role as a political headquarters. The force of Espace Niemeyer’s desire to be adored and admired means it only associates with those from whom it has something to gain. It gravitates towards those who can feed its appetite for flattery. It enjoys being courted by the elite of the fashion world, by Prada, Dior, and the likes of Louis Vuitton and Jean-Paul Gaultier. Espace Niemeyer deceives Le Siège and the French Communists by creating the illusion that their ties with culture are as strong as ever, and by bringing new audiences into the building. And this the French Communists become complicit in the building’s narcissistic drive, hiring out Espace Niemeyer as the backdrop for photo shoots, catwalks and music videos (Figure 11). Laced through this appeal to the glitterati are some worthy causes from time to time. Yet no one can openly talk about this new direction or criticise it, which pleases Espace Niemeyer because it has fragile self-esteem. The building’s continued importance in the guise of Espace Niemeyer has continued to rise from 2000 until the present day, with Espace Niemeyer eclipsing both Le Siège and the PCF headquarters. If there are any cannibalistic tendencies, they lie with Espace Niemeyer, who is slowly swallowing Le Siège and La Maison in a bid to break with the past and align with the forces of capitalism and free enterprise, so that it can feed its own ego and narcissistic tendencies.

Figure 11

Documentation of the periphery of a film shoot in the Delegation Room within Espace Niemeyer (Photograph by Sophie Warren and Jonathan Mosley: Courtesy of SICC).

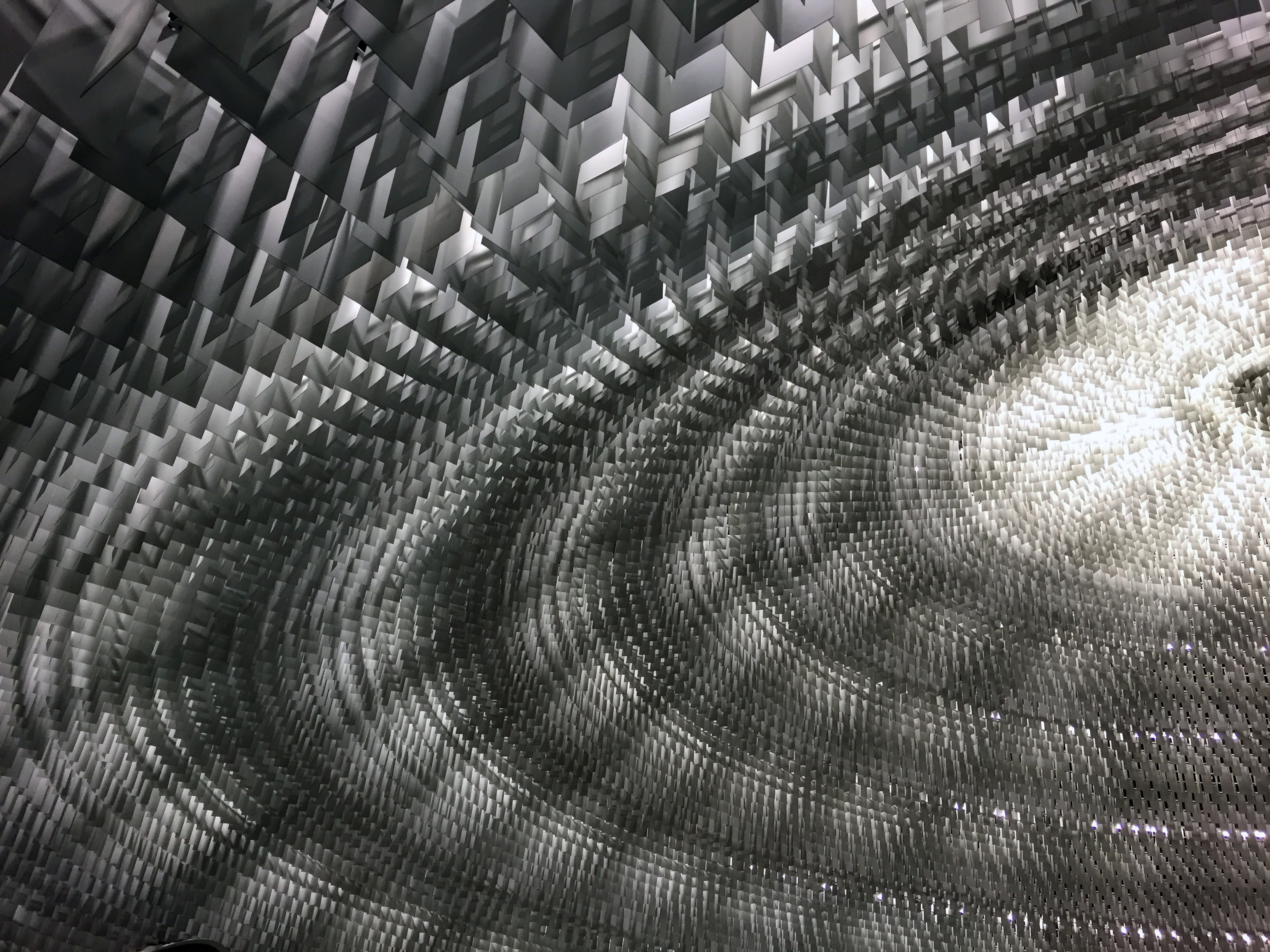

A second theme is that of coming face-to-face with your double. Le Siège has had a prolonged encounter with the uncanny. In the Espace Niemeyer, Le Siège saw its mirror image. For a long time, they were inseparable. It was consoling at first To see a reflection of itself, the double reaffirming Le Siège’s presence in a foreign land. Espace Niemeyer was so familiar to Le Siège, the differences between them were barely perceptible, apart from the change in name. Now when Le Siège steals a glance at Espace Niemeyer a shiver runs through its six storeys and takes fright below ground. It was the ease with which Espace Niemeyer staged its curvaceous forms, celestial dome, and inclined planes as objects of glamour for the appreciation and consumption of new audiences (Figure 12). Le Siège had tacitly acknowledged these qualities about itself, but was also in fear of them – the fear that one day pure form would overcome and eclipse function. The spectacular had been inscribed within its form and was now at the service of the photographic lens. There was something in this forced encounter with the unwanted aspects of the self, a premonition of death [40]. Le Siège thus comes face-to-face not with an older self, as one might expect, but a younger, shinier, rejuvenated self who threatens to extinguish its life and its desire to remain as a political headquarters.

Figure 12

The beautiful lamellae ceiling within the Salle du Comité General (General Committee room) of the PCF headquarters. The ceiling was added during construction to mitigate the excessive acoustic focusing of the dome, dispersing the sound to the many, and has become renowned for its visual aesthetic (Photograph by Sophie Warren and Jonathan Mosley: Courtesy of SICC).

A third theme is that of the building as a migrant with a bite. Le Siège is an outpost of Brasilidade in Paris. It flamboyantly flouts European modernism by infecting the rectilinear with the curvilinear. In the spirit of Cultural Cannibalism [29], it resists being incorporated by European modernity. Rather, it bites back, a dangerously playful bite, ingesting that which it finds meaningful in European modernism and then irreverently hybridising its motifs with the exuberance of the tropical irrational. The sensuality of curves and the freedom of liquid concrete pours and adornment set Le Siège apart from European modernism. In its anthropophagy a sensuality is brought to bear on the masculine clean lines of the latter. This affords the building a sense of gender fluidity, a queerness in the fabric, and the building’s identity: its constituent parts are somewhere between masculine and feminine.

Le Siège also firmly breaks from the governing codes of the great urban planner, Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann. Cutting loose from Haussmann’s spatial logic, Le Siège generously opens up its corner plot facing onto Place du Colonel Fabien. It invites the passer-by to traverse its inclined and oblique planes, willing a seamless journey from the pavement across its front esplanade to the bureau underside. No matter how well located it is, its architectural difference, flamboyance, and gender fluidity set it apart. Far away from the hills of Rio de Janeiro, Le Siège does not belong. Perceived as queer and ‘otherly’, it is a foreigner in Haussmann’s Paris. Its presence is alien. No place is home. Niemeyer was also a migrant in 1965, a refugee escaping Brazil’s dictatorship following the failure of a Utopian socialist regime, but he was embraced on his arrival to France. Le Siège, at the time of its inauguration, was despised by the national press who ridiculed it, accusing it of being a concrete bunker, a missile silo [41]. With the press casting aspersions and spreading lies, Le Siège suffered from the painful realisation that it may never belong or be embraced by the Parisians. Even the comrades seemed a little uncertain about its outward appearance.

The notion of a building being considered a migrant had already played out on this site in the form of the Melnikov Pavilion. This precursor building was as transgressive as Le Siège and as much an outpost in Paris. Konstantin Melnikov’s pavilion, an example of Soviet Russian Constructivism, and used as a workers’ university, was exchanged for the Brazilian-designed Modernist Baroque headquarters as a ‘house’ of the workers. The pavilion, transgressive to Stalin’s cultural policy, may have presaged the new cultural direction of the PCF. In 1966 the Central Committee of PCF at Argenteuil made a stand for creative freedom and breaking with Socialist Realist art [42]. This newfound freedom paved the way for a new kind of architecture for the PCF headquarters, then in the process of being commissioned.

The theme of conflict and resistance can also be identified in the site’s history, the previous PCF headquarters, and the PCF itself, thereby colouring the building’s psychological profile. A history of resistance characterises the site and was crucial to the success and acceptance of the PCF in France after the Second World War. Communists had played a pivotal role in the war-time resistance against fascism. This was acknowledged in the renaming of the building’s location after a Communist resistance fighter, Colonel Fabien. The previous PCF headquarters had been relatively small, scattered over separate buildings across Paris which had been subject to attacks both before and after the war. This made the new building’s name, ‘Le Siège’, particularly apt in its English rather than French meaning, as being ‘under siege’. The underground nature of France’s partisan resistance in the Second World War is reflected in the physical subterranean spaces of Niemeyer’s building and the lack of easily identifiable access to the building. All the significant assembly spaces are underground, hidden from public view. This can be seen as an aspect of fight – but also flight – that is etched into the very fabric of the building (Figure 13).

Figure 13

Vehicle ramps down to the underground floors of the PCF headquarters (Photograph by Sophie Warren and Jonathan Mosley: Courtesy of SICC).

However, the use of underground spaces is part of Niemeyer’s architectural language. On a small corner site, going underground is an architectural solution that allows a more open setting for the built forms above ground. The erection of a perimeter fence around this setting, shortly after the PCF headquarters were inaugurated, was a defensive manoeuvre to protect against attacks. This fundamentally changes the character and meaning of Niemeyer’s underground spaces. The party’s previous headquarters, perfectly assimilated into a streetscape of Hausmann pedigree, had been the target of fascist aggression. Now public access is denied and the open civic space that Niemeyer envisaged for the esplanade is made obsolete. Entry to the headquarters is through invitation only. The building this appears to take flight below ground as if it is literally under siege. The perimeter fence writes in the potential of obsolescence for the PCF headquarters as a ‘House of the People’ whose doors appear firmly shut. As speculation, if the esplanade had been open to the street and the people, as intended, would it be a natural site to host contemporary forms of political assembly and direct democracy that have seized public spaces like Place de la République? Could it welcome the 99%?

Flight also takes form in some of the aesthetic qualities of Le Siège’s internal spaces which are reminiscent of spaceships and what is now termed Retro-Futurism. Flight can also be linked in a broad sense to aspects of denial or blind spots or erasures. One such example of possible denial on the part of the PCF is manifested in the transparency of the glass curtain-wall of the Bureau – the curved office block of the headquarters that sits centrally on the site. Does its transparency speak of a longing for a proper appearance for the democratic transparency of administrative and political activities? Or does it present only the illusion of political transparency and deny actual political and social relations that depend on secrecy and security? At the heart of Le Siège somewhere between its transparent and hidden forms there lies an antagonism.

The final theme is that of memorialisation. By 2007 the PCF headquarters was declared a national monument. The theme of memorialisation can be tracked from the early years, in the history of resistance, place names, plaques, and funerals of significant figures such as Louis Aragon being held within the building itself. The status of the National Monument is attributed to the building in its guise as Espace Niemeyer. Memorialisation speaks to the wish to remember but is also the fixing in time and space of a past that is no longer living. It is instrumental in our sense of belonging and in shaping our collective national identity. Monuments are triggers for our collective memory and these are set in stone or within this building, in concrete. The timing of any memorialisation asks whose history is important or valued?

Espace Niemeyer has been eclipsing Le Siège since 2000 when it opened its doors to the public and began earning its keep by renting out space to fashion/beauty/music brands. This appears to erase the building’s history as a political headquarters and destabilises an associated collective identity. Instead, it marks a time that speaks of very different values; of the cult of personality in the figure of Oscar Niemeyer; of spectacular architecture no longer anchored to a utopian dream for social equality. Instead, the building appears dedicated to and itself consumed by fashion and advertising. Both our collective and individual identities are always shifting and acquiring different meanings. Perhaps the memorialisation of Espace Niemeyer best expresses the time we live in, with all its associated speed and erasure? Memorialisation speaks of an ancestor. So, the question that remains is whether the ancestor has been put to rest or, as is suggested here, it still haunts the beautiful building that has outlived it. Memorialisation can be prone to intergenerational processes in which something being remembered can get fixed in a manic form that has an ideology, unacknowledged trauma, or disavowal within it. This is in contrast with more depressively informed memorialisation, where the origins of the memory are more fully embodied and acknowledged. With a structure as complex as Espace Niemeyer, it may be that previously less acknowledged aspects of the building, present from the outset, become more apparent as time goes on and political, and cultural circumstances change. The need to ‘rememorialise’ may be currently uppermost in the mind as a new future focus is sought.

Figure 14

View of the PCF headquarters from Place Colonel Fabien showing the fence that separates the esplanade from the street (Photograph by Sophie Warren and Jonathan Mosley: Courtesy of SICC).

Conclusion: Intervening in the ‘psychostructure’

This essay has sought to demonstrate through this case-study that architecture as a whole can be radically reconceptualised as a psychological subject. Through transdisciplinary dialogue, a team consisting of a conceptual artist, a psychotherapist, a psycho-social researcher, and an architectural practitioner/researcher, have re-tuned methods derived from psycho-social studies, psychoanalysis, and conceptual art to explore the consciousness and unconsciousness of architecture. These methods are practice-based and participatory and together constitute an innovative method set that can be operationalised in a bespoke manner to address specific architectural assemblages. The method set has been tested on one such building, Le Siège du Parti Communiste Français, also known as Espace Niemeyer, also known as La Maison. The building as a psychological subject was profiled revealing several themes that arose consistently within the findings, triangulated between data from employing different methods. These findings produce a deep understanding of some of the relational dynamics within the architectural assemblage over time.

In answer to the unconscious hopes, fears, and aspirations found within the profiling, we make the following speculative recommendations in the form of interventions to the building’s ‘psychostructure’, with this term being understood here as the psychological dimensions of an architectural assemblage, entwined with that assemblage, both relational and built, conscious and unconscious). Firstly, regarding the longing for political significance, and the wish to be a home for the people, as well as to get beyond the fear of attacks, we recommend the removal of the fence that cordons off the headquarters from the streets and Place Colonel Fabien. This would change the identity of the front esplanade to become a publicly accessible open space, with associated dynamics and opportunities for public contact with the architecture (Figure 14). Additionally, to reinforce this shift in identity, we recommend the opening and signposting of the entrance foyer – known as the ‘Hall of Workers’ – as an accessible public venue, with events that are able to attract diverse audiences. Secondly, more related to identity issues, the status of National Monument accorded recently goes some way to acknowledging the building’s value and its belonging in France. Identity issues within the assemblage may be helped by renaming the building under one identity, to bring together diverse activities, allow for the co-existence of differences and coalesce the cultural and political impulses inherent in the building over time. And thirdly, we recommend the curation of an evolving exhibition located within the PCF headquarters that re-memorialises traumatic events, makes conscious the psychological hauntings, and constitutes the reworking of the repressed within the architectural assemblage.

These speculative interventions to the ‘psychostructure’ would be proposed as triggers for discussion with the communities of the building. Their therapeutic potential is to recode or re-territorialise the assemblage through the alteration of forms of content and expression of the assemblage, thereby creating new emerging capacities and affective inter-relationships. They have the potential to enhance the wellbeing of users and passers-by, and with minimal resources also enhance the utility and regard of the building, countering any threats of its demise or obsolescence. Even to the extent that the profiling deepens stakeholders’ understanding of the complexity of the architecture as entangled with human and non-human materiality and immateriality, this research project affords robustness to the relationship of the building to its communities, which will help sustain it over time.

This paper thus seeks to embody and activate ecological thinking as thinking about affect and interconnectedness between different entities, in the ways described by Morton and Bennett [12; 13]. As such, the project offers a radical ecological and transdisciplinary way of thinking about architecture that includes psychological and social dimensions. It runs counter to the notions of buildings being consumable or solely units of investment. Instead, it engenders holistic evaluation that engages with the lifespan of architectural structures and their relational entanglement. It offers a new methodological framework from ontological considerations through to methodology and a coherent set of innovative transdisciplinary methods applicable to different contexts and case studies. These approaches and the tools put forward apply to architectural practice, the management of buildings, and participatory practices for public empowerment over built environments and are also potentially scalable from building subjects up to urban/landscape situations. The radicality of this approach is in its proposition that practicing architecture towards sustainability becomes primarily about producing and managing the internal relational dynamics and psychology of architectural assemblages; casting architects as facilitators and stewards of occupied built environments; not just designers of the built but of the living.

Acknowledgements

The researchers express their profound gratitude to: the Parti Communiste Français and building manager Nicolas Bescond; Gerard Fournier of Espace Niemeyer; project architect Jean deRoche; residency liaison Mathilde Villeneuve; Ricardo Espada, João Magalhães, Mauricio Martins at Jack the Maker; Patrick Thornhill, Ben Starling, Tom Garne at Bristol UWE for assistance with the ‘Deputised Object’; Group O (Julian Manley, Paul Hoggett, Tim Hockridge, Ursula Murray, Lindsey Stewart, Sandra Harrison, Penny McLellan, Gun Kjellberg) for their participation in the Visual Matrix. The artist/researcher residency for Sophie Warren and Jonathan Mosley was funded by the Institut Français, through an award of international artist laureate, and by the British Council and Arts Council England through award of International Artist Development Fund. The initial inter-disciplinary dialogue was funded by a Connecting Research Award through Bristol UWE.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.