Anesthesiologists are accepted as aiming to be outstanding in patient safety and medical quality improvement. However, both preventable and inevitable adverse events still persist [1, 2]. According to the Thai Anesthesia Incidents Study (THAI Study) database, the incidence of perioperative cardiac arrest within 24 h was 31:10,000 in 2005 with a mortality rate of 90% [3, 4]. The Royal College of Anesthesiologists of Thailand (RCAT) initiated knowledge management tools using research to improve anesthesia processes and outcomes. Several strategies have been engaged to improve patient safety across the country. The subsequent Thai Anesthesia Incidents Monitoring Study (Thai AIMS) was initiated in 2007 using incident reports among 51 hospitals across Thailand using the concept of “from routine to research, and from research to routine practice” [5, 6]. There were several consequent changes to anesthesia practice guidelines and technology, such as using pulse oximetry as a mandatory monitoring procedure that have been implemented. With this continuous improvement process, RCAT subsequently hosted the Perioperative and Anesthetic Adverse Events in Thailand (PAAd Thai) study in 2015 [7]. The aim of this study was to investigate the incidence of perioperative and anesthesia adverse events, contributing factors, factors minimizing outcomes, and to suggest strategies to avoid specific adverse events.

The present prospective multicentered study, a part of the PAAd Thai study, was conducted by the RCAT between January 1 and December 31, 2015. All anesthesiologists and nurse anesthetists in 22 participating hospitals across Thailand were asked to report critical incidents on an anonymous basis.

After being approved by each institutional ethics committee, informed consent was exempted. The specific anesthesia-related adverse events detected during anesthesia and during the 24 h postoperative period were reported by completing a standardized incident reporting form as soon as possible after the occurrence of adverse or undesirable events. These events included pulmonary aspiration, suspected pulmonary embolism, esophageal intubation, endobronchial intubation, oxygen desaturation (<85% or <90% for >3 min), reintubation, difficult intubation (>3 times or >10 min), failed intubation, total spinal block, awareness during general anesthesia, coma/cerebrovascular accident/convulsion, nerve injury, transfusion mismatch, suspected myocardial infarction/ischemia, severe arrhythmia (such as: atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, second or third degree atrioventricular block, ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, bradycardia <40 beats/min), cardiac arrest, death (all causes), suspected malignant hyperthermia, anaphylaxis/anaphylactoid reaction/allergy, drug error, equipment malfunction/failure, suspected emergence delirium, wrong patient/site/surgery. Oxygen desaturation in the present study was defined as SpO2 below 90% for >3 min or once below 85% as detected by pulse oximetry. The anesthesia profiles, surgical profiles, and narrative description of incidents were also recorded. Details of the present study methodology have been described [7]. All incident record forms and monthly reports of anesthesia statistics were verified by the site manager and sent to the data management unit at the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University. Descriptive statistics used for analysis were determined using SPSS for Windows, version 22 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Each critical incident of the first 2,000 incidents was reviewed by a group of reviewers and will be presented in subsequent PAAd Thai Studies.

Between January 1 and December 31, 2015, some 333,219 patients underwent anesthesia in the 22 participating hospitals. Among these, the main anesthetic techniques used were 216,179 cases of general anesthesia (64.8%), 27,191 cases of general total intravenous anesthesia (8.2%), 15,793 cases of monitored anesthesia care (4.7%), 62,102 cases of spinal anesthesia (18.6%), and 1,895 cases of epidural anesthesia (0.6%).

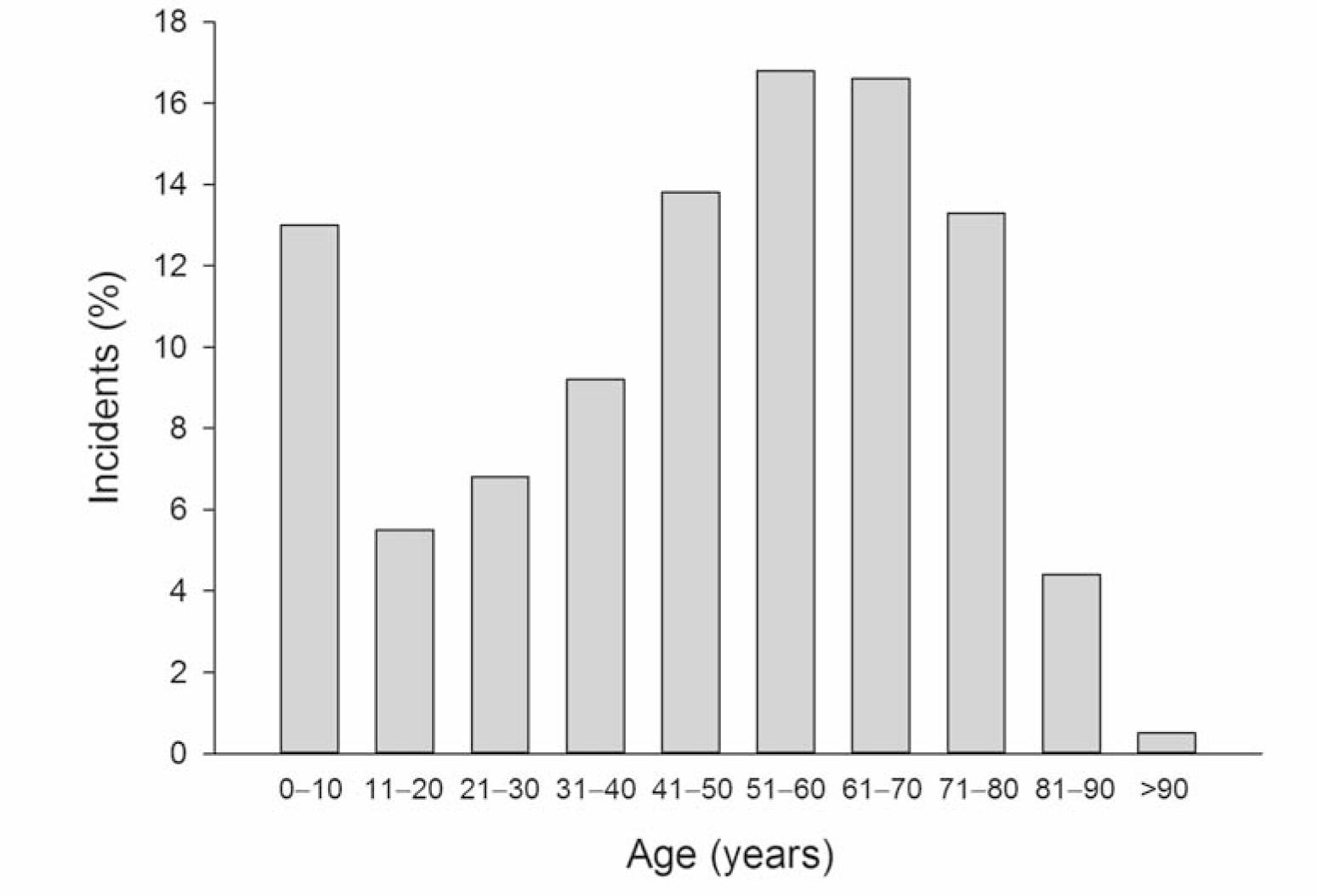

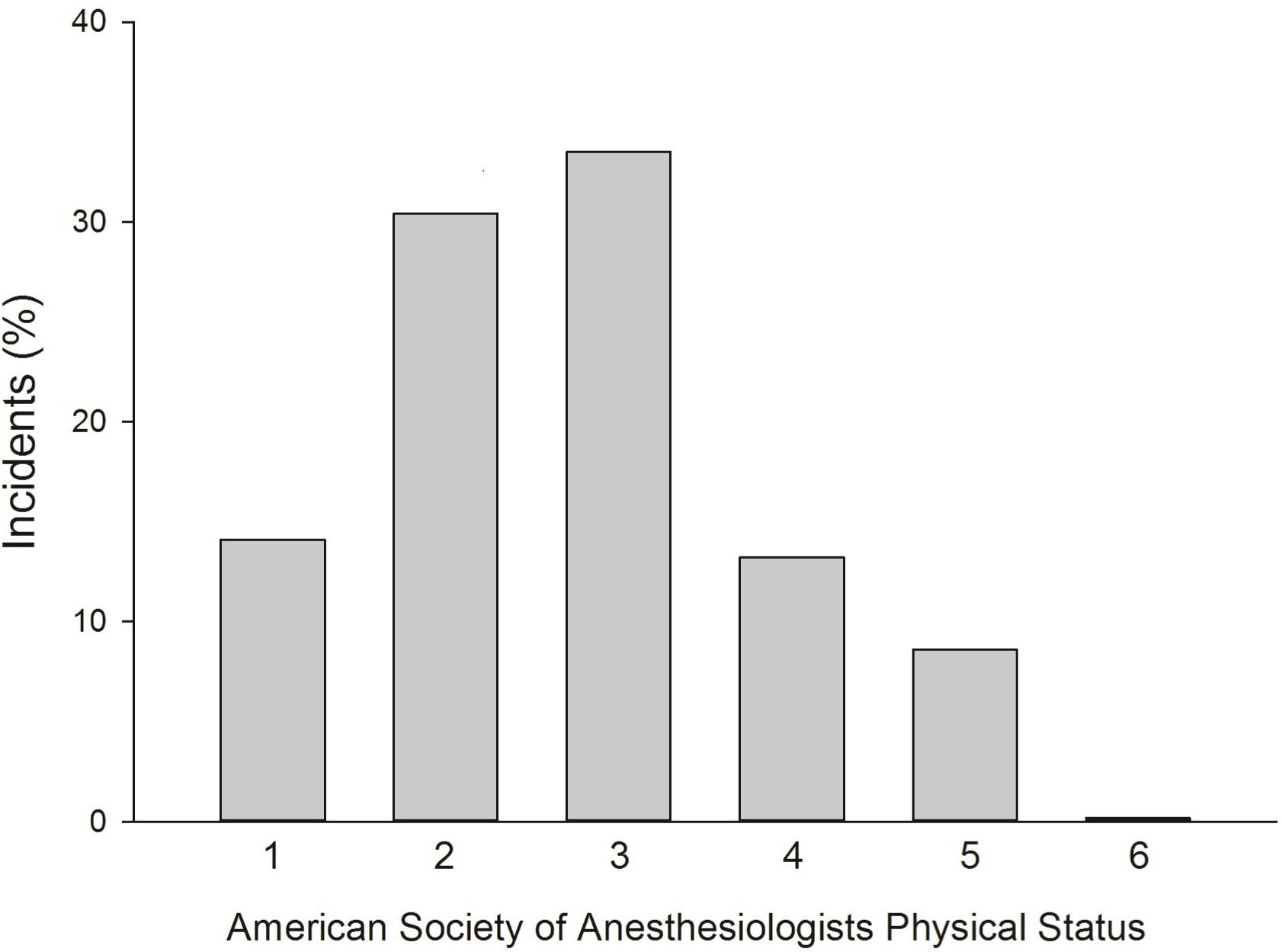

After screening by the site manager of each hospital and the project manager (SC), 2,206 incident report forms with 3,028 critical incidents were sent to the data management unit. The 22 public hospitals representing all regions of Thailand were recruited as the PAAd Thai study participants [7]. The age of patients reported varied from 1 day to 97 years with a male:female sex ratio of 1,136:1,050 (52%:48%). Figures 1 and 2 respectively show the distribution of age and American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status (ASA PS) classification of patients in the PAAd Thai database.

Age distribution of patients in 2,206 incident reports

ASA physical status classification of patients in 2,206 incident reports

Among 2,206 incident reports, general surgery, orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery, cardiac surgery, and gynecological surgery accounted for 64.8% of the surgery with critical incidents. Details of the site of surgery or operation are shown in Table 1. Monitoring equipment used during anesthesia is shown in Table 2.

Operation or operative site of surgery in 2,206 incident reports

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| General surgery | 690 (31.3) |

| Orthopedic | 267 (13.0) |

| Neurosurgery | 168 (7.6) |

| Cardiac | 148 (6.7) |

| Gynecological | 137 (6.2) |

| Otorhinolaryngological | 127 (5.8) |

| Thoracic | 117 (5.3) |

| Urological | 111 (4.9) |

| Endoscopic | 85 (3.9) |

| C-section | 74 (3.4) |

| Vascular | 71 (3.2) |

| Ophthalmological | 69 (3.1) |

| Plastic | 47 (2.1) |

| Dental | 24 (1.1) |

| Intervention | 24 (1.1) |

| Minimally invasive | 19 (0.9) |

| Diagnostic | 8 (0.4) |

| Electroconvulsive | 2(0.1) |

| Radiotherapy | 2(0.1) |

Remark: numbers are not mutually exclusive

Monitoring equipment used during anesthesia in 2,206 incident reports

| Monitoring equipment | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Pulse oximeter | 2188 (99.2) |

| Electrocardiograph | 2180 (98.8) |

| Sphygmomanometer (noninvasive blood pressure) | 2144 (97.2) |

| Capnometer | 1789 (81.8) |

| Spirometer | 1005 (45.6) |

| End tidal gas analyzer | 820 (37.2) |

| Invasive arterial pressure monitor | 531 (24.1) |

| Thermometer | 476 (21.6) |

| Central venous pressure catheter | 402 (18.2) |

| Oxygen analyzer | 391 (17.7) |

| Pulmonary arterial pressure analyzer | 37 (1.7) |

| Echocardiograph | 25 (1.1) |

| Electroencephalograph | 12 (0.5) |

| Cardiac output monitor | 7 (0.3) |

Remark: numbers are not mutually exclusive

Information regarding the phase of anesthesia relevant to incident reports and location is shown in Table 3. Practitioners of anesthesia during which critical incidents occurred were anesthesiologists (51.9%), nurse anesthetists (44.9%), anesthesia residents (34.3%), nonanesthesia residents (1.1%), surgeons (0.4%), anesthesia nurse trainees (8.5%), and medical students (1.5%). The incidents classified by perioperative periods are shown in Table 4. There was a case report of suspected malignant hyperthermia in a university hospital.

Phase and location of occurrence of incidents (N = 2,206 reports)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Phase | |

| Preinduction | 112 (5.1) |

| Induction | 496 (22.5) |

| Maintenance | 761 (34.5) |

| Emergence | 152 (6.9) |

| Recovery | 224 (10.2) |

| Postoperative 24 h | 381 (17.3) |

| Location | |

| Induction room | 15 (0.7) |

| Operating room | 1433 (65.0) |

| Recovery room | 235 (14.6) |

| Intensive care | 167 (7.6) |

| Delivery room | 3 (0.1) |

| Ward | 239 (10.8) |

| Imaging unit | 10 (0.5) |

| During transportation | 14 (0.6) |

| Others (gastrointestinal endoscopy unit, | 6 (0.2) |

Remark: numbers are not mutually exclusive

Critical incidents classified by perioperative periods for 2,206 incident reports and overall incidence

| Critical incidents (N = 2,206 reports) | Overall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operative period n (%) | Postanesthesia care unit n (%) | Postoperative 24h n (%) | Total (N = 2,206) n (%) | Incidence (95% Cl) per 10,000 | |

| Pulmonary aspiration | 30(1.4) | 1(0.1) | 2(0.1) | 33(11.5) | 1.36(0.89,1.82) |

| Suspected pulmonary embolism | 14(0.6) | 4(0.2) | 1(0.0) | 17(0.8) | 0.51(0.27,0.75) |

| Esophageal intubation | 184(8.3) | – | – | 184(8.3) | 8.51(7.28,9.74) |

| Endobronchial intubation | 24(1.1) | – | – | 24(1.1) | 1.11(0.67,1.55) |

| Oxygen desaturation | 342(15.5) | 119(5.4) | 17(0.8) | 465(21.1) | 13.95 (12.69,15.00) |

| Reintubation | 63 (2.9) | 113(5.1) | 66(3.0) | 240(10.9) | 11.10(9.70,12.51) |

| Difficult intubation | 172(7.8) | 2(0.1) | – | 173 (7.8) | 8.00(6.81,9.19) |

| Failed intubation | 16(0.7) | – | – | 16(0.7) | 0.74(0.38,1.10) |

| Total spinal block | 2(0.1) | – | – | 2(0.1) | 0.32 (–0.12,0.77) |

| Awareness during general anesthesia | – | – | 10(0.5) | 10(0.5) | 0.41(0.16,0.67) |

| Coma/cerebrovascular accident/convulsion | 8(0.4) | 11(0.5) | 39(1.8) | 53 (2.4) | 1.59(1.16,2.02) |

| Nerve injury | 5(0.2) | 1(0.1) | 16(0.7) | 21(1.0) | 0.63(0.36,0.90) |

| Transfusion mismatch | 4(0.2) | 3 (0.2) | – | 7(0.3) | 0.21(0.05,0.37) |

| Suspected myocardial infarction/ischemia | 20(0.9) | 4(0.2) | 14(0.6) | 34(1.5) | 1.02(0.68,1.36) |

| Severe arrhythmia | 467(21.2) | – | – | 467(21.2) | 14.01 (12.74,15.29) |

| Cardiac arrest within 24 h | 255(11.6) | 9(0.4) | 272(12.3) | 519(23.5) | 15.58(14.24,16.91) |

| Death within 24 h | 107(4.9) | 5(0.3) | 330(15.0) | 442(20.0) | 13.26(12.03,14.50) |

| Anaphylaxis/anaphylactoidreaction/allergy | 67(3.0) | 14(0.6) | 1(0.0) | 79(3.6) | 2.37(1.85,2.89) |

| Drug error | 104(4.7) | 1(0.1) | 2(0.1) | 107(4.9) | 3.21(2.60,3.82) |

| Equipment malfunction/failure | 47(2.1) | – | 2(0.1) | 4.7 (2.1) | 1.41(1.01,1.81) |

| Anesthesia personnel hazard | 2(0.1) | 15 (0.7) | – | 17(0.8) | 0.60(0.34,0.97) |

| Suspected emergence delirium | 2(0.1) | 15 (0.7) | – | 17(0.8) | 0.60(0.34,0.97) |

| Wrong patient/site/surgery | 6(0.3) | – | – | 6(0.3) | 0.18(0.04,0.32) |

Remark: numbers are not mutually exclusive

The detection of incidents by clinical diagnosis in the database of 2,206 incident reports were in 2,003 cases (96.8%), of which the clinical diagnosis was achieved before in 860 cases (41.5%) and after diagnosis by monitoring equipment in 1,008 cases (48.7%). The diagnosis of incidents was achieved by monitoring alone in 203 cases (9.8%) or clinical skill alone in 135 cases (6.6%).

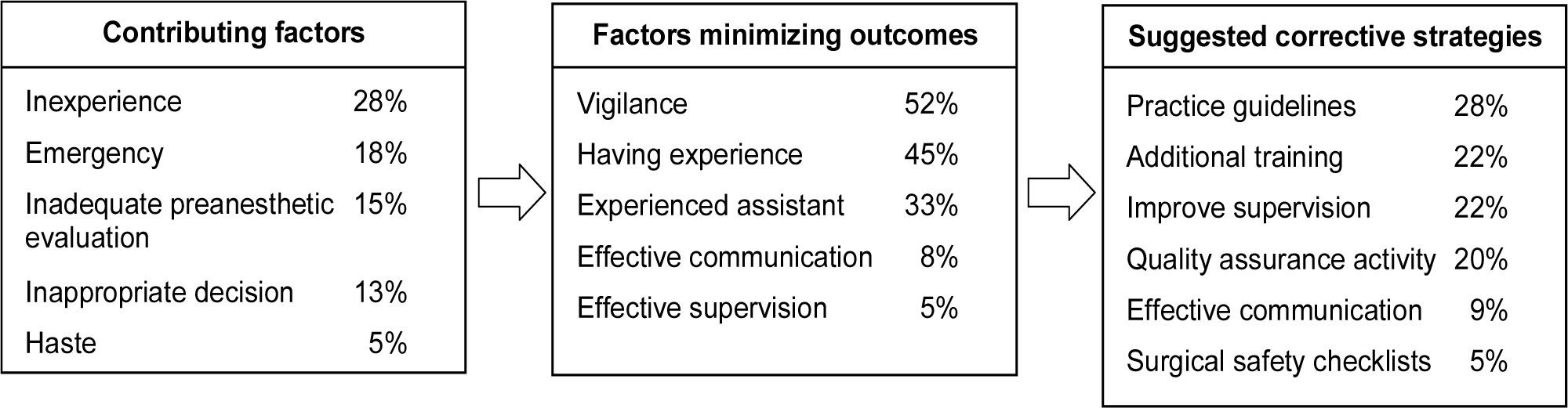

The immediate and long-term outcomes are shown in Table 5. According to the opinions of attending personnel and site manager of each hospitals, contributing factors are shown in Table 6, factors minimizing outcomes are shown in Table 7, and suggested corrective strategies to avoid the occurrence of incidents are shown in Table 8.

Immediate and long-term (7-day) outcomes for 2,206 incident reports

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Immediate outcomes | |

| Complete recovery | 553 (25.1) |

| Death | 432 (19.6) |

| Major physiological change | 326 (14.8) |

| Respiratory | 207 (9.4) |

| Cardiovascular | 91 (4.1) |

| Neurological | 66 (3.0) |

| Cardiac arrest | 261 (11.8) |

| Unplanned intensive care unit admission | 163 (7.4) |

| Minor physiological change | 72 (3.3) |

| Prolonged emergence | 20 (0.9) |

| Awareness | 7 (0.3) |

| Unplanned hospital admission | 5 (0.2) |

| Other | 79 (3.6) |

| Long-term (7-day) outcomes | |

| Complete recovery | 265 (12.0) |

| Death | 249 (11.3) |

| Prolonged hospital stay | 144 (5.2) |

| Prolonged ventilator support | 132 (6.0) |

| Disability | 6 (0.3) |

| Vegetative stage | 6 (0.3) |

| Psychic trauma | 2 (0.1) |

| Other | 7 (0.3) |

Factors contributing to the incidents (N = 2,206 reports)

| Contributing factors | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Noncompliance with surgical safety checklists | 35 (1.6) |

| Inappropriate decision | 307 (13.9) |

| Inadequate knowledge | 125 (5.7) |

| Inexperience | 630 (28.6) |

| Haste | 188 (8.5) |

| Fatigue | 11 (0.5) |

| Inadequate personnel | 24 (1.1) |

| Communication defect | 86 (3.9) |

| Not familiar with environment | 6 (0.3) |

| Emergency condition | 418 (18.9) |

| Inadequate preanesthetic evaluation | 333 (15.1) |

| Inadequate preanesthetic preparation | 116 (5.3) |

| Inadequate equipment | 35 (1.6) |

| Inefficient equipment/monitoring | 55 (2.5) |

| Monitor not available | 8 (0.4) |

| Error in drug label | 29 (1.3) |

| No recovery room | 4 (0.2) |

| Blood bank problems | 21 (1.0) |

Factors minimizing incidents in 2,206 incident reports

| Factors | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Compliance with surgical safety checklists | 105 (4.8) |

| Having experience | 995 (45.1) |

| Experienced assistant | 736 (33.4) |

| Vigilance | 1150 (52.1) |

| Adequate personnel | 32 (1.5) |

| Effective supervision | 129 (5.8) |

| Effective communication | 186 (8.4) |

| Improvement of training | 75 (3.4) |

| Adequate equipment | 83 (3.8) |

| Adequate maintenance | 44 (2.0) |

| Equipment check up | 57 (2.6) |

| Adequate monitoring equipment | 85 (3.9) |

| Comply to practice guidelines | 189 (8.6) |

| Other | 58 (2.6) |

Suggested corrective strategy for prevention of occurrence of incidents (N = 2,206 reports)

| Factors | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Compliance with surgical safety checklists | 114 (5.2) |

| Compliance with guidelines | 638 (28.9) |

| Additional training | 502 (22.8) |

| More manpower | 87 (3.9) |

| Improvement of supervision | 497 (22.5) |

| Improvement of communication | 209 (9.5) |

| More equipment | 76 (3.4) |

| Equipment maintenance | 59 (2.7) |

| Quality assurance activity | 452 (20.5) |

| Good referral system | 33 (1.5) |

| Other | 38 (1.7) |

The PAAd Thai study was conducted using incident reporting as a tool to improve the safety and quality of anesthesia in Thailand. An incident reporting system can be a powerful tool for complex systems such as anesthesiology, and has been of proven benefit in aviation, nuclear power plants, and the oil industry [8]. It is based on the potential to learn from critical events [9, 10]. In 2005, the RCAT launched the Thai Anesthesia Incidents Study (THAI Study), a registry documenting the incidence of anesthesia-related adverse events [3, 4]. In 2007, the RCAT initiated the Thai Anesthesia Incidents Monitoring Study (Thai AIMS) to investigate the occurrence of anesthesia-related complications on a voluntary and anonymous basis in an attempt to improve clinical practice guidelines, monitoring techniques, and education [5, 6, 11]. The present PAAd Thai study revealed the current status of surgery, anesthesia, and their adverse events after a decade of continuing safety, and quality improvement in a developing country.

During the 12-month period of the present study, 2,206 incident reports of 3,028 incidents were screened by the site manager and project manager and sent to the data management center. The first 2,000 incidents reported were reviewed by at least 3 senior anesthesiologists to investigate contributing factors, factors minimizing outcomes, and strategies suggested using the model developed by the Australian Anesthesia Incident Monitoring Study [12, 13]. In our multicentered study, a total of 333,219 anesthetic procedures were performed with 64.8% of general anesthesia, 8.2% of general anesthesia total intravenous anesthesia (GA TIVA), 4.7% of monitored anesthesia care (MAC), 18.6% of spinal anesthesia, and 0.6% of epidural anesthesia as consistent with a previous study [4]. The incidence of specific adverse events was calculated by using appropriate denominators. In Thailand, all regional anesthetic procedures are performed exclusively by physicians or certified anesthesiologists. Nurse anesthetists are legally allowed to performed general anesthesia in public hospitals. Trainees such as residents, anesthesia nurse students, and medical students can provide anesthesia under supervision of attending personnel. Therefore, the status of the practitioner and type of hospital such as “university”, or “nonuniversity” may affect specific outcomes. This will be analyzed and reported in subsequent articles.

Compared with our previous incident report, patients in the PAAd Thai Study were in general older than those of the Thai AIMS. The age of two-thirds of patients in the present study was between 41 and 80 years, while the age of 70% of patients in the Thai AIMS were between 31 and 60 years. The possible explanations are that the Thai population is aging as a society, and patients with older age have better accessibility to surgery and possibility experience more critical incidents. About 13% of perianesthetic adverse events occurred in patients <10 years old and about 18% in patients >70 years old (Figure 1). Patients at age extremes, that is pediatric and geriatric patients, generally have a higher risk of adverse events [14, 15].

Compared with the female:male sex ratio of 5.3:4.7 in the THAI Study that represented patients undergoing surgery in Thailand, the female:male sex ratio of patients in the PAAd Thai study was 4.8:5.2. The more frequent incidence of critical events that occurred in male patients was similar to that found in previous studies [6]. The proportion of patients in the PAAd Thai study was consistent with the Thai AIMS because both studies were confined exclusively to patients who experienced critical incidents. More than half of incident reports occurred in ASA PS groups 3, 4, and 5. However, critical incidents also occurred in patients with normal or mild systemic diseases (ASA PS of 1 and 2) comprising 44.5% (Figure 2). Therefore, attending anesthesia personnel should remain vigilant for adverse events in patients receiving surgery with no underlying disease.

The common operative sites or types of surgery reported to have critical incidents in the present study (Table 1) were consistent with the Thai AIMS [6]. Therefore, neurological, otorhinolaryngological, and cardiothoracic surgeries posed a high risk for occurrence of critical incidents. Adverse events occurred frequently in emergency situations (36.5%).

The objective of monitoring is to augment clinical observation for the attending anesthesia practitioner and to help decision making during the administration of anesthesia and other treatments. The present study showed that pulse oximetry, electrocardiography, and NIBP were most common monitoring used during anesthesia (Table 2). This finding showed that the RCAT was successful in implementing clinical practice guidelines regarding monitoring with pulse oximetry since 2007. Use of pulse oximetry was changed to be mandatory by the RCAT one year before the World Health Organization campaign for global oximetry in 2008. The proportion of capnometer use during general anesthesia in the present study was high because of their increased availability in medical institutions. The results may support the feasibility of the RCAT policy in using a capnometer as mandatory monitoring equipment during general anesthesia.

Among the incident reports, common phases of anesthesia when critical incidents occurred were the induction and the maintenance phases (Table 3). The common locations where incidents occurred were in the operating room, ward, and postanesthesia care unit. In the Australian Incident Monitoring Study, the common sites where critical incidents occurred were the operating theater (75%), induction room (10%), and recovery room (6%) [13]. A possible explanation for the differences is that separate induction rooms are rarely designated in Thai hospitals. The phases and locations of incidents in the present study were similar to those found in our previous study [6]. Therefore, anesthetic personnel should pay attention during the preanesthetic period, such as during preanesthetic evaluation and preparation. There was empirical evidence that use of a preinduction checklist improved information exchange and perception of safety in the anesthesia team [16].

About half of the perianesthetic adverse events that occurred within 24 h were respiratory system complications such as oxygen desaturation, reintubation, suspected pulmonary aspiration, and esophageal intubation (Table 4). Analysis of these common critical events will be subsequently published to identify corrective strategies that can be suggested. The incidence of difficulty with intubation in the present study was 8.0:10,000 revealing a dramatic decrease from that observed in our previous study. In 2006, our registry showed that the incidence of difficult intubation was 22.5:10,000 [4] and over part of a metaanalysis that the modified Mallampati score was inadequate as a single test for difficult laryngoscopy [13, 17]. Subsequent study regarding esophageal intubation will consider appropriateness and feasibility of using capnometry as mandatory monitoring for general anesthesia in a national context in Thailand. The incidence of 24 h perianesthetic cardiac arrest and mortality (all causes) in the PAAd Thai Study were 15.5 and 13.2 per 10,000 respectively, which were lower than those in the THAI Study, which found incidence rates of 30.8 and 28.3:10,000 respectively [4]. These dramatic decreases showed substantial safety improvement of anesthesia and surgery in government hospitals in Thailand. There were several continuous quality improvement activities, such as improvement of clinical practice guidelines according to national evidence, and improvement in monitoring, training, and an increase in the number of anesthesia practitioners in the government sector [18, 19, 20]. Like the Thai AIMS, common critical incidents in the recovery room were oxygen desaturation and reintubation. Sun et al. [21] found that hypoxemia was common and prolonged in patients recovering from surgery. The present study confirmed that the incidence of malignant hyperthermia in Thailand was between 1:150,000 and 1:200,000 patients receiving general anesthesia [22].

The immediate outcomes were death, major physiological change; including respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurological problems; and unplanned intensive care unit admission. However, one-quater of incident reports experienced complete recovery. For late outcomes within 7 days, the common outcomes were death, prolonged ventilator support, and prolonged hospital stay, while 12% of reports were of patients with complete recovery (Table 5).

A model of anesthesia-related adverse events comprised of contributing factors, factors minimizing incidents, and suggested preventive strategies is shown in Figure 3.

Model of anesthesia related adverse events in the Perioperative and Anesthetic Adverse Events in Thailand (PAAd Thai) study

The current PAAd Thai incident reporting study resembles story telling or a collection of organizational experience. The lessons learnt can be used locally in hospitals and at a national level, and include improvement of clinical practice guidelines, monitoring, improvement of system factors, and education including both knowledge and anesthesia nontechnical skill. For example, the use of a capnometer should be considered in a substudy regarding esophageal intubation. Some common or rare, but serious critical incidents should be selected as topics for simulation training, and study of anesthesia nontechnical skills in residency and nurse anesthetist training.

The present study has some limitations. First, incident reports were on an anonymous basis, some soft outcomes or incidents might be under-estimated. However, we organized several meetings and workshops before the participating hospitals agreed to participate in this multicenter project in an attempt to minimize this problem. Second, there were differences between the PAAd Thai study 2015 and the Thai AIMS 2007, such as the 12 month vs 6 months period; and 22 hospitals vs 51 hospitals. Most of the hospitals providing incident reports were the same and familiar with incident reporting system and its definition as declared by the Royal College of Anesthesiologists of Thailand. Third, uncertainty remains, especially of reporting bias. We did not know if: all incidents that happened have been reported, which were reported or were not reported, how many incidents have not been reported. However, we did an interim analysis after 6 months of study and compared findings with those at the end of 12 months of data collection. We found the incidence of hard outcomes such as cardiac arrest within 24 h, death within 24 h, esophageal intubation, and difficult intubation were all comparable.

In the past decade, the incidence of most anesthetic adverse events decreased in Thailand. The dramatic reduction in the perioperative cardiac arrest and difficult intubations displays marked improvement in anesthetic care. The majority of adverse events are respiratory and cardiovascular complications. However, in the postanesthesia care unit, oxygen desaturation, and reintubation are leading causes.

The common contributing factors for critical incidents were inexperience, emergency conditions, inadequate preanesthetic evaluation and preparation, and inappropriate decision making. By contrast, the factors minimizing incidents were vigilance and advanced experience. Suggested corrective strategies are improvement in compliance with practice guidelines, quality assurance activity, continuing education, and improvement of supervision.