1 Introduction

“Heavy metal” (or simply “metal”) music is a form of rock music that emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s with bands like Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, and Deep Purple (Herbst and Mynett, 2023; Hjelm et al., 2011). It is characterized by distorted guitars, pounding rhythms, as well as overall loudness and lyrical content that has been denounced as “evil” by conservative groups.1 From the 1980s onwards, heavy metal spawned a plethora of subgenres (such as black metal, death metal, viking metal, and nu metal) with distinct symbols, lyrical content, and music styles. Despite the complexity of heavy metal and its subgenres and their often controversial characteristics, studies often analyze and contextualize only a few songs or bands in detail (Conway and McGrain, 2016; Doesburg, 2021; Granholm, 2011; Herbst, 2021; Oksanen, 2011; Sellheim, 2019; Spracklen, 2017a, 2017b; Spracklen et al., 2014), or contextualize individual subgenres, or specific topics (e.g. occultism) historically or culturally (Farley, 2016; Hjelm et al., 2011; James and Walsh, 2018; Otterbeck et al., 2018; Rafalovich and Schneider, 2005). To date, there has been no attempt to map the topics and their relation to music systematically from a computational perspective.

To fill this gap, we conduct a computational study of two major defining aspects of metal music: the lyrics and the “hardness” of the sound (usually referred to as “heaviness” in metal music studies; see Section 2.2). We analyze 124,288 metal song lyrics using Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA, Blei et al., 2003) and interpret the resulting themes based on the tokens most strongly associated with each topic extracted. We also develop an audio model for hardness of metal music, which is evaluated via listening tests and is readily interpretable because it is a linear combination of essential audio features. The relation between textual topics and the audio-based hardness model is then explored and expanded by subgroup analyses on the level of metal subgenres. This article builds upon a conference paper on hardness in metal music (Czedik-Eysenberg et al., 2017), with the main new contributions being all lyrics-related analysis including exploration of relations between lyrics and audio hardness in the context of different subgenres.

To this end, the paper is structured as follows: In Section 2, we review related work and explicate our contribution, and in Section 3, we describe all methods related to analyzing the audio and lyrics corpora. In Section 4, we present our results, which we discuss and conclude in Section 5.

2 Related Work and Our Contribution

We discuss related work concerning computational lyrics analysis in general as well as analysis of metal lyrics in particular. We review results concerning hardness in metal music audio and work on combining audio and lyrics information. We also explain our contribution to addressing the identified gaps in previous research.

2.1 Lyrics analysis

The lyrics of vocal music are an important layer of information, as they convey emotional expression, topics, and stories that can greatly influence a listener’s impression of songs. The field of lyrics-related studies has been termed “lyrics information processing” (LIP), sharing core technologies with both natural language processing (NLP) and MIR (Watanabe and Goto, 2020). Important aspects of LIP include lyrics structure analysis (e.g. rhyme scheme identification (Addanki and Wu, 2013), verse-bridge-chorus labeling (Mahedero et al., 2005)), and lyrics semantic analysis, including estimating the mood or emotion of lyrics (Delbouys et al., 2018; Hu and Downie, 2010; Mishra et al., 2021) or modeling different topics in lyrics (Kleedorfer et al., 2008; Sasaki et al., 2014; Sterckx et al., 2014). Most of these studies, however, focus on practical applications, e.g. using lyrics for new retrieval interfaces (Sasaki et al., 2014). Using large-scale lyrics data to explore the cultural evolution of popular music, others have shown e.g. a decrease in lexical and structural complexity (Parada-Cabaleiro et al., 2024) and an increase in negatively valenced emotion over the past decades (Napier and Shamir, 2018) and modeled the cultural dynamics related to this trend (Brand et al., 2019). While shedding light on temporal dynamics and popular genres/charts music, these studies did not investigate particular subcultural genres in detail to study genre-specific lyrical topics.

As for lyrics specifically from the metal genre, to the best of our knowledge no computational analysis exists so far, but these lyrics have been investigated in musicology, sociology, and cultural studies (Farley, 2016). Such approaches typically use small lyrics corpora, including a couple of thousand lyrics at best. For example, Rafalovich and Schneider (2005) analyzed a convenience sample of lyrics printed in more than 200 metal booklets. Focusing on the topics of psychological chaos, nihilism/violence, and alternative religiosity, they argue that the content provides means for listeners to negate mainstream culture and to empower them within marginalized social positions. Cheung and Feng (2021) analyzed a corpus of 1,152 heavy metal songs and focus on the 11 most common terms in their corpus, such as “death,” “fear,” and “darkness”.

Besides these more general inquiries, other studies analyze lyrics of only a small number of songs. Some studies focus on specific regions: e.g. on two Scottish black and folk metal bands (Spracklen, 2017a), four British black metal bands (Spracklen et al., 2014), two East Asian bands (Birnie-Smith and Robertson, 2021), or two Finnish metal songs (Doesburg, 2021). Other studies focus on the depiction of certain topics, often in specific subgenres, e.g. violence, religion, and Norsemen in Scandinavian black, death, and viking metal (Sellheim, 2019).

The depiction of religion in metal lyrics is an important focus in many studies. The preoccupation with occult themes, satanism, and the devil was a founding element of heavy metal. Integrating these topics into the lyrics, appearances, and music became a common ground for the emergent black and death metal subgenres in the 1980s (Farley, 2016). According to the analyses of small text corpora, addressing blasphemous acts, violence against organized religion and its proponents, as well as religious hypocrisy are part of the meta-narrative of black metal (Otterbeck et al., 2018; Podoshen, 2018; von Helden, 2010). In these songs, a medieval form of language is employed to evoke a subverted feeling of being part of a dark, hellish, and violent ceremony.

Our contribution is a computational lyrics analysis of a much larger corpus of metal music than has ever been studied before.

2.2 Audio hardness in metal music

In the case of metal music, sound dimensions like loudness, distortion, and, particularly, hardness (or heaviness)2 play essential roles in defining the sound of this genre (Berger and Fales, 2005; Herbst, 2017; Mynett, 2013; Reyes, 2008). The quality of hardness (heaviness) has slowly gained increasing attention in recent years within musicology, cultural studies, and, particularly, metal music research (Herbst and Mynett, 2023; Miller, 2022; Volák, 2022). Originally, the relatively few acoustic investigations focused specifically on the timbre of the metal guitar (Berger and Fales, 2005; Herbst, 2017, 2018). The metal guitar’s sound is typically characterized by high levels of distortion, which emerged as a defining feature of the genre in the course of its formation (Herbst, 2017). Acoustically, this is apparent in a dense sound that has an increased high-frequency energy and noise ratio in certain frequency ranges and a flatter dynamic envelope (Berger and Fales, 2005). Perceptually, distortion can lead to higher perceived overall loudness due to its dynamic compression effect, as well as—particularly in interaction with harmonic complexity—increased sensory dissonance (Terhardt, 1976), which is being related to the genre’s striving for increased heaviness (Herbst, 2017, 2018).

A distorted impression is also a characteristic element of the sound of metal vocals. Depending on the subgenre, metal vocals are often characterized by a noisy, rough, and inharmonic timbre due to the use of extreme vocal styles like growling/grunting and screaming (Mesiä and Ribaldini, 2015). This is reflected in a decreased harmonics-to-noise ratio (HNR) in the audio signal (Kato and Ito, 2013; Nieto, 2013) and reduces the intelligibility of the lyrics, especially for non-expert listeners (Olsen et al., 2018).

Distorted bass guitars, drum styles like blast beats,3 and double bass,4 together with techniques like “palm muting”,5 which emphasize transients and a percussive staccato character (Mynett, 2019), are among the many elements that contribute to a sound that is overall noisier and less harmonically clear. A layering of particularly the rhythm guitar might enhance even more the building of a “dense wall of distortion” (Herbst and Mynett, 2023, p. 23).

Harmonically, besides the use of power chords6 in many metal genres, minor tonality is a characteristic, especially in black metal (Jordan and Herbst, 2023), and also atonality and harmonic complexity might influence overall hardness (Berger and Fales, 2005; Herbst and Mynett, 2023).

Overall, multiple diverse elements related to composition, production and performance can contribute to hardness (Herbst and Mynett, 2022; Mynett, 2019). Recently, Herbst and Mynett (2023) offered an overview mapping out a systematic understanding of the quality, particularly in regard to the issue of achieving a heavy sound in contemporary metal music production.

In summary, most studies on hardness/heaviness in metal music focus on the production side, often using qualitative analysis methods, while there is a lack of music perception studies, as well as no usage of larger-scale datasets.

Our contribution is the construction and human perceptive evaluation of an audio model of musical hardness based on essential audio features that are related primarily to distortion and noisiness.

2.3 Combination of audio and lyrics

As audio and text features provide complementary layers of information on songs, a combination of both data types has been shown to improve the automatic classification of high-level attributes in music such as genre, mood, and emotion (Delbouys et al., 2018; Hu and Downie, 2010; Kim et al., 2010; Laurier et al., 2008; Neumayer and Rauber, 2007). Multi-modal approaches interlinking these features offer insights into possible relations between lyrical and musical information, such as systematic connections between melodic patterns and text features (Nichols et al., 2009), common factors affecting lyrical and audio content in the emergence of mood (McVicar et al., 2011), or learning the cross-modal correlation of temporal structures in audio and lyrics (Yu et al., 2019). Most recent approaches use multimodal embedding models (Huang et al., 2022; Oramas et al., 2018), e.g. to combine pre-trained language models and audio information to study lyrics content (Zhang et al., 2022).

Though many of the previous multi-modal investigations primarily aimed at improving genre or mood detection or recommender systems, in our opinion, understanding these intercorrelations offers the great potential to shed light on the relationship between genre-defining audio qualities and lyrical content.

Concerning metal lyrics, investigations have so far been limited to individual cases or relatively small corpora (with a maximum of 1,152 songs in Cheung and Feng (2021)), and the relationship between the musical and the textual domains has not yet been explored at all.

Our contribution therefore is to examine the association between topics present in a large corpus of metal song lyrics and the perceived hardness of the respective songs. This is done for the whole genre of metal music as well as separately for its subgenres.

3 Methodology

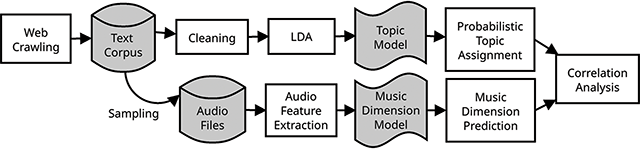

We employ a sequential research design and begin by downloading a metal lyrics corpus from www.darklyrics.com. After standard cleaning procedures (see Appendix A), this resulted in a corpus of l = 124,288 lyrics. We then extracted topics from the corpus using LDA, a widely used topic modeling algorithm (Blei et al., 2003). For a subset of these songs, audio features were extracted using an audio feature model for hardness based on listening experiments. The use of automatic models for the extraction of both text as well as musical features allows for scalability as it enables a large corpus to be studied without depending on the process of manual annotation for each song. The resulting feature vectors were then subjected to a correlation analysis. Figure 1 outlines the sequence of the steps taken when processing the data. The individual steps are explained in the following subsections. Please note that reproducibility of results is limited because audio and lyrics cannot be shared due to copyright reasons. However, lists of all songs used in the perceptual studies (Section 3.2) as well as the correlation analysis (Section 3.3) are provided with MusicBrainz recording IDs in a data repository.7

Figure 1

Processing steps of the approach, illustrating the parallel analysis of text and audio features.

3.1 Topic modeling via latent dirichlet allocation

We extracted topics from the lyrics corpus using LDA (Blei et al., 2003), which tries to model latent topics in large amounts of text. Its basic entities are documents and words therein (in our case, lyrics of songs). The documents are organized in a bag-of-words format, meaning that word order and grammar are ignored and words are counted per text instead. The assumption is that topics manifest in the co-occurrence of words among documents (lyrics). Therefore, these latent topics are then modeled as probability distributions over word occurrences. Simultaneously, the LDA assigns a probability distribution of topics across documents, endeavoring to optimize the separation of documents over topics. The assumption here is that different documents contain information about rather different (and fewer) topics, but of course overlaps are allowed. However, the number of topics is assumed to be known a priori, which is why it is necessary to calculate and compare models with different .

We selected a model with a specific based on calculating coherence (Röder et al., 2015) as a goodness-of-fit measure and a qualitative evaluation of the topics. Two of the authors investigated each model using LDAvis (Sievert and Shirley, 2014), considering the ten most relevant and salient terms per topic. The saliency of the terms according to Chuang et al. (2012) is defined as the product of the probability for observing a term and the term’s distinctiveness, measuring how informative a term is for determining the topic it is produced by. The ten most salient terms for each topic of the final model are reported in Table 1. As an additional step, we analyzed the 10 lyrics documents that were most strongly associated with each topic, further validating our initial interpretation of each topic of the models under scrutiny. After this step, the authors compared and discussed their initial interpretations of each topic and noted the interpretation they agreed upon. A full account of calculating the LDA and the goodness-of-fit measure is provided in . Based on this procedure, we decided on topics.

Table 1

Overview of the resulting topics found within the corpus of metal lyrics () and their correlation to hardness obtained from the audio signal (see Section 4.2), *: : (Bonferroni-corrected significance level). Terms are presented in their stemmed format (e.g., “fli” instead of “fly” or “flying”).

| Topic | Interpretation | Salient Terms (Top 10) | Hardness |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | personal life | know, never, time, see, way, take, life, feel, make, say | −0.238** |

| 2 | sorrow & weltschmerz8 | life, soul, pain, fear, mind, eye, lie, insid, lost, end | −0.005 |

| 3 | night | dark, light, night, sky, sun, shadow, star, black, moon, cold | −0.114* |

| 4 | love & romance | night, eye, love, like, heart, feel, hand, run, see, come | −0.260** |

| 5 | religion & satanism | God, hell, burn, evil, soul, Lord, blood, death, satan, demon | 0.144** |

| 6 | battle | fight, metal, fire, stand, power, battle, steel, sword, burn, march | 0.129* |

| 7 | brutal death | blood, death, dead, flesh, bodi, bone, skin, cut, rot, rip | 0.292** |

| 8 | vulgarity | fuck, yeah, gon, like, shit, little, head, girl, babi, hey | 0.054 |

| 9 | archaisms & occultism | shall, upon, thi, flesh, thee, behold, forth, death, serpent, thou | 0.144** |

| 10 | epic tale | world, time, day, new, end, life, year, live, last, earth | 0.009 |

| 11 | landscape & journey | land, wind, fli, water, came, sky, river, high, ride, mountain | −0.113** |

| 12 | struggle for freedom | control, power, freedom, law, nation, rule, system, work, peopl, slave | 0.090* |

| 13 | metaphysics | form, space, exist, beyond, within, knowledg, shape, mind, circl, sorc | 0.057 |

| 14 | domestic violence | kill, mother, children, pay, child, live, anoth, father, name, innoc | 0.067 |

| 15 | dystopia | hum, race, disease, breed, destruct, machin, mass, seed, destroy, earth | 0.245** |

| 16 | mourning rituals | ash, word, dust, stone, speak, weep, smoke, breath, tongu, funer | 0.043 |

| 17 | (psychological) madness | mind, twist, brain, mad, self, half, mental, terror, urg, obsess | 0.103* |

| 18 | royal feast | king, rain, drink, fall, crown, sun, rise, bear, wine, color | −0.028 |

| 19 | rock ’n’ roll lifestyle | rock, roll, train, addict, explod, wreck, shock, chip, leagu, raw | 0.042 |

| 20 | disgusting things | anim, weed, ill, fed, maggot, origin, worm, incest, object, thief | 0.087 |

Finally, we used the LDAvis package to analyze the structure of the resulting topic space. In this vein, we applied multidimensional scaling (MDS) to project the inter-topic distances onto a two-dimensional plane (Borg and Groenen, 2003) (see Appendix C).

3.2 High-level audio feature extraction

The high-level audio feature model that was used had originally been constructed in previous examinations focusing on the perception of hardness in music (Czedik-Eysenberg et al., 2017, 2018). In those music perception studies, ratings were obtained for 212 music stimuli in two online studies by 40 raters each. In both experiments, the majority of participants were students of musicology. Informed consent to participate in the studies was obtained from the participants in accordance with university and international regulations.

Study 1: Subjects were asked to rate perceived hardness of music excerpts on a seven-point Likert scale (with seven corresponding to the highest level of perceived “hardness”). The stimuli included 62 songs from a wide range of music genres, which were trimmed to 10-s excerpts of the chorus (with a few exceptions) and presented to subjects in random order. Forty participants from German-speaking countries were recruited to take part in the experiment (mean age: male, 15 female), with each subject rating each excerpt.

Study 2: A similar second listening survey was conducted using 150 music stimuli that consisted of 15-s excerpts taken from the chorus of songs belonging to the genres metal, pop, techno, and gothic. The stimuli were presented in random order to subjects who, in this case, rated them on a slider from −1 to 1 (starting in the neutral position 0) in terms of perceived hardness. Again, 40 subjects participated in the listening test (mean age: male, 15 female, 1 diverse).

With regard to inter-rater reliability (according to mean pairwise correlation, Cronbach’s and Krippendorff’s α), subjects showed moderate to high agreement when rating the excerpts (see Table 2). This indicates a higher clarity of the concept compared to rating many other music dimension descriptors (such as rhythmic complexity, articulation, modality, energy, or valence (Friberg et al., 2014)).

Table 2

Inter-rater reliability in terms of mean pairwise correlation between raters ( in each experiment), Cronbach’s , and Krippendorff’s .

| Mean pairwise correlation | Cronbach’s | Krippendorff’s | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | 0.772 | 0.992 | 0.698 |

| Study 2 | 0.665 | 0.987 | 0.590 |

Based on this ground truth, a multiple linear regression model with audio features as explanatory variables and hardness as the predicted response was estimated. Chosen features are primarily related to audio distortion and noisiness.

The list of used audio features, as implemented in LibROSA (McFee et al., 2015) (v0.10.1) and Essentia (Bogdanov et al., 2013) (v2.1b6.dev1034), can be found in Table 3. With regard to frame lengths and hop sizes, the default parameters of the Essentia music extractor were used (half-overlapping frames of 2,048 samples duration for low-level features and 4,096 for higher-level features). For spectral contrast, which was extracted via LibROSA, a window length of 2,048 samples with a hop length of 512 samples was used. Pitch confidence was computed using a window length of 2,048 samples and a hop length of 128 samples with the MELODIA algorithm (Salamon and Gómez, 2012) implemented in Essentia. Framewise features were aggregated using the mean across time frames.

Table 3

Audio features included in the linear model for hardness, along with their unstandardized and standardized coefficients and p values. Sorted by absolute standardized coefficient descending.

| Audio feature | (std) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| −0.190 | −0.250 | < 0.001 | |

| HPCP Entropy | 0.741 | 0.196 | 0.003 |

| Spectral Complexity | 0.031 | 0.192 | 0.002 |

| Dissonance | 13.856 | 0.163 | 0.026 |

| Pitch Confidence | −8.943 | −0.162 | 0.002 |

| Diatonic Strength | −2.439 | −0.159 | < 0.001 |

| Scale | −0.202 | −0.112 | 0.003 |

The spectral contrast describes the energy contrast between the peak and the valley (top and bottom quantiles, respectively) of the spectrum (Jiang et al., 2002). With lower spectral contrast values in the octave band between 1,600 and 3,200 Hz, a noisier, less clear signal can be observed in this frequency range. HPCP entropy corresponds to the Shannon entropy of the Harmonic Pitch Class Profile (HPCP). Spectral complexity is a measure of complexity based on the number of peaks in the spectrum. Dissonance is an estimation of the sensory dissonance (perceptual roughness) of the sound based on psychoacoustic dissonance curves (Plomp and Levelt, 1965). Pitch confidence was extracted on the harmonic signal after harmonic/percussive source separation (Fitzgerald, 2010). It corresponds to the confidence with which a pitch could be detected when trying to extract the predominant melody using the MELODIA algorithm (Salamon and Gómez, 2012). Diatonic strength is an estimation of the key strength based on a high-resolution HPCP using a diatonic profile.

In the case of the feature scale, the mean across three different scale estimation variants was used in order to achieve more robust scale detection performance for different styles of music. Those estimations were obtained by using three different key profiles implemented in Essentia (“Krumhansl,” ”‘Temperley,” and “EDMA”). Negative values correspond to higher probability of a minor scale.

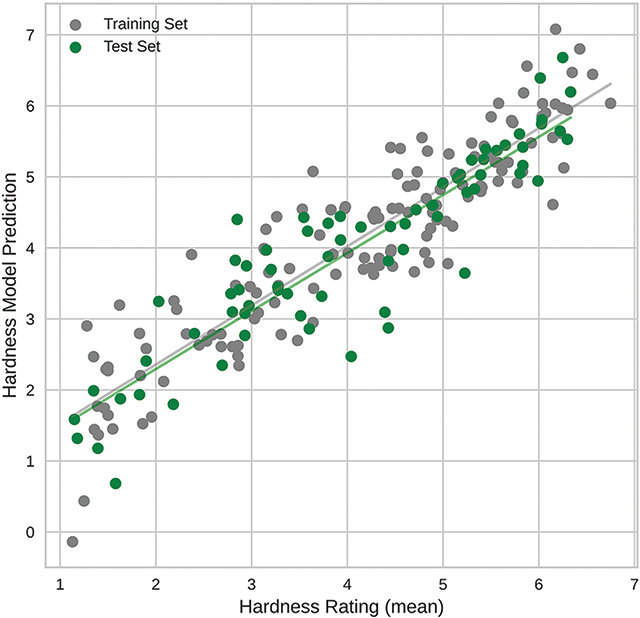

For the model used in this work, the ratings from both experiments were combined (after rescaling all to the same scale of ), resulting in a dataset of 211 rated examples in total. This is less than the sum from studies 1 and 2 because one example had been included for comparability reasons in both experiments. This dataset was split into a training set and a test set . On the training set, the linear regression model was estimated using five-fold cross-validation, resulting in an value of 0.832. The final model was then evaluated using the previously separated test set (see Table 4). The coefficient of determination, , corresponds to the proportion of variance explained by the predictor variables. In the case of the training set, around of variance in the perceptual hardness ratings could be explained by the audio features in Table 3. The coefficient (adjusted) takes into account the number of predictors, penalizing larger models. The mean average error (MAE) and mean squared error (MSE) refer to the residuals of the model and show that, on average, the predicted values were wrong by approximately 0.5 point on the scale from 1 to 7 ( by about ). Table 3 displays the audio features included as predictors, as well as their coefficients and values within the trained regression model.

Table 4

Performance measures of the audio hardness model on the training and test sets.

| Training | Test | |

|---|---|---|

| 0.832 | 0.822 | |

| (adjusted) | 0.823 | 0.802 |

| MSE | 0.376 | 0.387 |

| MAE | 0.488 | 0.486 |

Figure 2 compares the prediction results obtained using the described audio feature model with the average human rating for each stimulus. Note that the fit of the model to the mean human ratings (Pearson’s on the test set) is actually higher than the mean pairwise correlation among the 40 raters (see Table 2).

Figure 2

Scatterplot showing the comparison between the mean hardness ratings given by human participants on the x-axis and the results of the audio feature–based hardness model on the y-axis (Pearson’s for the training set and for the test set).

3.3 Investigating the connection between audio and text features

Finally, we drew a random sample of 503 songs (see Appendix A) from the full database of songs and used Spearman’s to identify correlations between the topic probabilities over the songs and the hardness values predicted by the high-level audio feature model based on 15-s song excerpts. We opted for Spearman’s since it does not assume normal distribution of the data and is less sensitive to outliers and zero inflation than Pearson’s r. Bonferroni correction was applied in order to account for multiple testing.

The sample of 503 songs may appear small compared to the much larger size of the lyrics database, but results in Section 4 will show that it is sufficient to yield statistically significant correlations. For copyright reasons, larger music research datasets (e.g. the “Million Song Dataset” (Bertin-Mahieux et al., 2011)) do not contain the actual audio but only features derived from it. Since we need access to the raw audio for the analysis steps described in Section 3.2, we opted for a small but sufficient sample size that yields strong evidence at small monetary and computational costs.

4 Results

4.1 Lyrics analysis

Table 1 displays the 20 topics extracted from the text corpus in descending order according to their prevalence (weight). For each topic, a qualitative interpretation is given, along with the ten most salient terms.

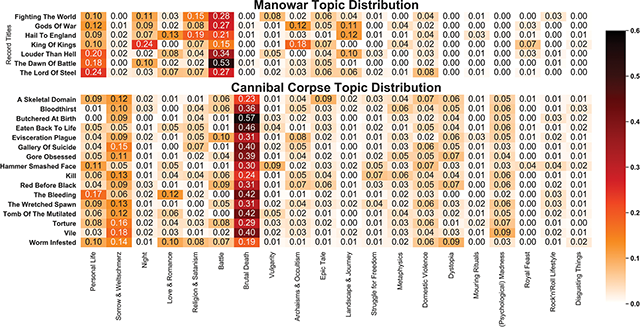

The salient terms of the first topic—and in parts also the second—appear to be relatively generic, as terms like “know”, ”never”, and “time” occur in many contexts. However, the majority of the remaining topics reveal distinct lyrical themes that have been described as being characteristic of the metal genre. This is highlighted in detail in Figure 3. Here, the topic distributions for two exemplary bands contained within the sample are presented. For these heat maps, the topic distributions of the lyrics were aggregated at the level of different albums over a band’s history. For the band Manowar, which is associated with the genre of heavy metal, power metal, or true metal, a prevalence of topic #6 (“battle”) can be observed, while a distinct prevalence of topic #7 (“brutal death”) becomes apparent for Cannibal Corpse—a band belonging to the subgenre of death metal.

Figure 3

Comparison of the topic distributions for all included albums by the bands Manowar and Cannibal Corpse, showing a prevalence of the topics “battle” and “brutal death”, respectively.

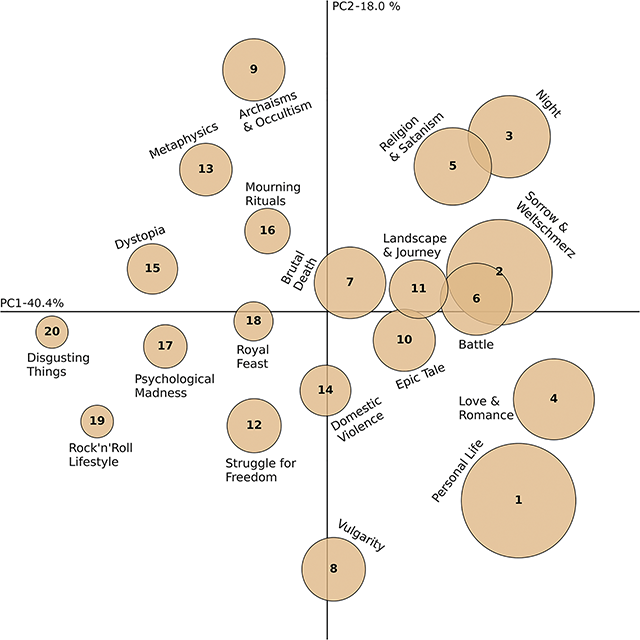

Within the topic configuration obtained via multidimensional scaling (see Figure 4), two latent dimensions resulting from principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) can be identified (PC1 and PC2). Overall, the first extracted dimension explains , and the second explains of the variance present in the text data. The first dimension (PC1—personal/impersonal) distinguishes topics dealing with personal life, often written in first-person narrative. This ranges from more personal topics on the right-hand side (#1, personal life; #2, sorrow & weltschmerz; and #4, love & romance) to more impersonal topics on the left-hand side (#15, dystopia; #19, rock’ n’ roll lifestyle; and #20, disgusting things). This also correlates to the weight of the topics within the corpus, as represented by the sizes of the circles, with the larger topics on the right-hand side. The second dimension (PC2—profane/transcendent) is characterized by a contrast between transcendent and sinister topics dealing with occultism, metaphysics, satanism, darkness, and mourning (#9, #3, #5, #13, and #16) at the top and comparatively profane content dealing with personal life and rock ’n’ roll lifestyle using a rather mundane or vulgar vocabulary (, and ) at the bottom.

Figure 4

Topic configuration obtained via multidimensional scaling. The radius of the circles is proportional to the percentage of tokens covered by the topics (topic weight). The x-axis has been termed PC1—personal/impersonal, and the y-axis has been termed PC2—profane/transcendent.

4.2 Combination of audio and lyrics

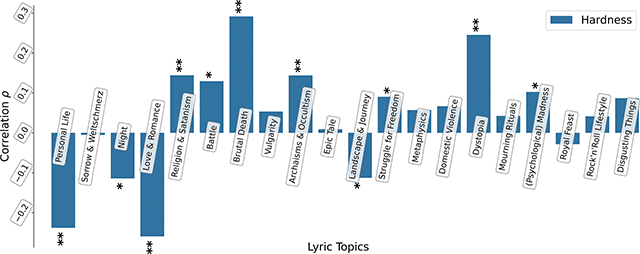

In the next step of our analysis, we calculated the association among the 20 topics discussed above and the hardness as a high-level audio feature using Spearman’s . The results are visualized in Figure 5, and the values are listed in the right-most column of Table 1. Significant positive associations (after Bonferroni correction) can be observed between musical hardness and the topics “brutal death”, “dystopia”, ”archaisms & occultism”, and “religion & satanism”, while it is negatively linked to the topics “personal life” and “love & romance”. Overall, the strength of the associations is moderate at best, with the strongest association existing between hardness and the topic “brutal death” ().

Figure 5

Correlations between lyrical topics and the audio hardness dimension; : : (Bonferroni-corrected significance level).

In accordance with previous studies (Doesburg 2021; Farley, 2016; Otterbeck et al., 2018; Podoshen, 2018; Sellheim, 2019; Spracklen, 2017a, 2017b; von Helden, 2010), we cannot assume a uniform distribution of topics across different metal subgenres. This is why we also evaluated the topics extracted via the LDA with more fine-grained genre metadata stemming from Encyclopaedia Metallum (EM). The EM is a source that has been used repeatedly in metal music studies (Bleile et al., 2022; DeHart, 2018; Friconnet, 2022). It has a thorough coverage of metal bands, records, and songs and yields comparatively high-quality annotation of the data, which is additionally controlled by the website administrators. Of the lyrics within our dataset stemming from 5,855 bands, 4,502 bands could be linked to genre metadata stemming from EM (), including all bands that recorded the subset of 503 songs for which we also analysed the audio (see Section 3.3). In EM, each band is assigned to either one or multiple genres and subgenres, of which we used only the first annotated genre. This yielded more than 50, partially obscure subgenres such as psychedelic/experimental black metal or raw experimental/industrial black metal, which we therefore aggregated into broader subgenre categories including a residual category (Else) combining all remaining smaller subgenres (see Appendix D for the merging procedure, the subgenre selection, and the full list of subgenres, with the total number of bands assigned to each).

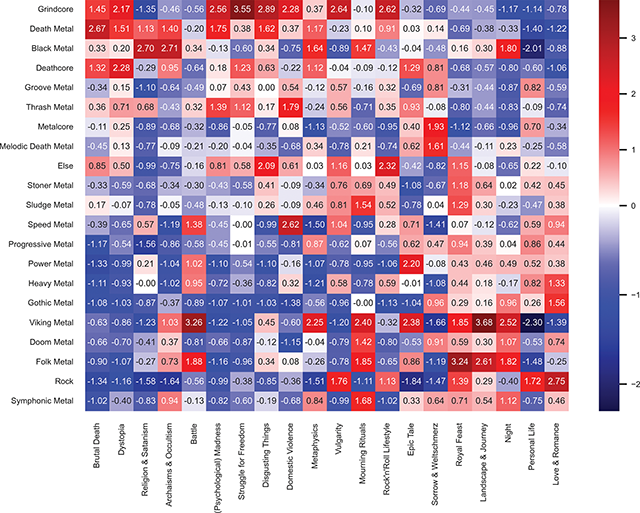

We then calculated the mean audio hardness per genre based on our audio sample by assigning each of the 503 songs from the audio sample to its first subgenre, according to EM, and sorted the genres in order of descending estimated hardness (the y-axis in Figure 6). In a second step, we sorted the topics by correlation with hardness in descending order (the x-axis in Figure 6). In order to account for uneven genre distributions, we z-standardized the topic prevalences column-wise by calculating the difference between each genre’s topic prevalence and the mean by topic divided by the standard deviation within each topic.

Figure 6

Heatmap of topic prevalence by genre, z-standardized. Subgenres and topics are sorted by established relation to audio hardness in decreasing order.

As seen in Figure 6, the hardest genres, according to the z-standardized audio hardness, are grindcore, death metal, black metal, and deathcore. With the exception of black metal, these genres especially focus on topics like brutal death, dystopia, (psychological) madness, domestic violence, and disgusting things. As another example in agreement with results from literature (Otterbeck et al., 2018; Podoshen, 2018; Sellheim, 2019; von Helden, 2010), black metal focuses on dark topics more than other topics, as seen in the high positive values for religion & satanism, archaism & occultism, metaphysics, mourning rituals, and night.

Turning to the genres with the lowest audio hardness (symphonic metal, rock, folk metal, doom metal, and viking metal), we see a focus on the depictions of landscapes & journey, night, royal feast, and—in the case of rock—on love & romance and on personal life. Additionally, viking and folk metal combine these topics with the battle topic.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

We have presented a corpus study of metal music, a specific form of rock music that has enjoyed enduring popularity for more than 50 years. Our corpus study has examined the textual topics found in song lyrics and investigated the association between these topics and a high-level audio feature. Our main results are:

(1) A computational lyrics analysis of an unprecedented number of metal songs, where the obtained prevalent text topics are a confirmation of previous qualitative analyses of much smaller corpora (Cheung and Feng, 2021; Farley, 2016; Rafalovich and Schneider, 2005). These topics include religion & satanism, dystopia or disgusting objects, but also brutal death and battle. An exemplary exploration of two typical metal bands as well as of topic distributions across metal subgenres showed that different topics are associated with different types of metal music. The themes identified in various small-scale qualitative studies (Birnie-Smith and Robertson, 2021; Farley, 2016; Otterbeck et al., 2018; Podoshen, 2018; Spracklen, 2017a; Spracklen et al., 2014; von Helden, 2010) for the black, death, and viking metal subgenres can also be found in our large text corpus. We were therefore able to corroborate and objectify previous results from the fields of musicology and metal music studies. Future studies could further expand on this analysis by examining lyrics by region, release year, and artist information, which can be retrieved as metadata from platforms such as Encyclopaedia Metallum.

(2) The construction of an audio model of musical hardness that is in line with musicological knowledge and validated with a human perceptive evaluation. This model of hardness is based on essential audio features as discussed in the respective literature on metal music (Berger and Fales, 2005; Herbst, 2018; Herbst and Mynett, 2023; Kato and Ito, 2013; Mynett, 2019; Miller, 2022). With most features relating to some aspect of noisiness and distortion (e.g. reduced spectral contrast, higher dissonance, and higher entropy of the HPCP), they represent the “dense wall of distortion” (Herbst and Mynett, 2023) described with regard to a heavy metal sound. Particularly, the reduced spectral contrast in the frequency band 1,600–3,200 Hz relates well to the “noise formant” above 1,500 Hz observed already by Berger and Fales (2005). The role of the scale estimation as a predictor (with negative coefficient) might reflect the importance of the minor scale in extreme genres like black metal (Jordan and Herbst, 2023). The multiple linear regression model estimated from these audio features is able to predict mean human ratings of musical hardness at the very high level of Pearson’s correlation above 0.9.

(3) Provision of evidence that perceived musical hardness is associated with harsh lyrical topics. In particular, we were able to show that musical hardness is associated with aggressive and intense topics like brutal death and dystopia, while it is negatively associated with relatively mundane topics concerning personal life and love. A detailed exploration of subgenres showed that metal music with high perceived audio hardness (e.g. grindcore or death metal) exhibits lyrical topics like brutal death, dystopia, domestic violence, or disgusting things. We also like to point out a potential paradox: for listeners paying attention also to the lyrical content, violent lyrics might contribute to the perceived overall hardness of a song. However, especially for genres with particularly dark and violent lyrics (e.g. death metal, black metal), the intelligibility of the lyrics is reduced due to elements that contribute to the perceived hardness, such as noisy vocals due to extreme vocal effects (screams, growls) (Olsen et al., 2018).

As a final note, we would like to state that a clear emphasis in our reported research was a tight integration with musicology in order to render our results accessible and meaningful to a musicological audience beyond the field of music information retrieval. This has been achieved by embedding our research in musicological results concerning metal music and by employing computational methods that stay close to the data and have a clear and straightforward interpretability. Therefore, our audio hardness model is based on a linear combination of essential audio features and not on e.g. an end-to-end, deep-learning model. A recent survey (Borsan et al., 2023) of 10 years of published MIR results has shown that there has been almost no impact on musicology because “the majority of new technologies [...] are, for an average musicologist, incomprehensible.” It is our hope that the results reported in this article will have an impact on musicological studies of metal music also.

Data Accessibility

Lists of the songs used in the listening experiments as well as in the analysis are provided, together with the corresponding MusicBrainz recording IDs at https://github.com/CPJKU/tismir_metal_music

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) [10.55776/P36653]. For open-access purposes, the authors have applied a CC BY public copyright license to any author-accepted manuscript version arising from this submission.

Competing Interests

Arthur Flexer is a member of the editorial board of the Transactions of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval. He was completely removed from all editorial processing. There are no other competing interests to declare.

Author Contributions

Isabella Czedik-Eysenberg conceptualized the project, conducted the listening experiments, performed modeling (primarily audio), interpreted topics, analyzed results, and co-wrote the initial draft. Oliver Wieczorek programmed the web crawler and performed modeling (primarily text), interpreted topics, analyzed results, and co-wrote the initial draft. Arthur Flexer significantly contributed to the writing, analyzing results and data curation. Christoph Reuter collected the audio datasets and provided resources. All authors contributed to the study design and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Additional File

The additional file for this article can be found as follows:

Notes

[2] A note on terminology: In metal music studies, the defining quality of the genre is usually referred to as “heaviness” (e.g. Berger and Fales, 2005). We refer to a closely related quality as “hardness” here in order not to restrict this feature dimension strictly to the metal genre, as it can be a relevant feature of other genres as well, such as (hard) rock or hardcore techno. Note that the perceptual experiments (see Section 3.2) were conducted in German, in which “hard” (“hart”) is the commonly used term when referring to the metal genre also, probably rendering the terminological distinction less relevant for German speakers.

[3] Very fast drum pattern typically consisting of 16th or 32th notes played alternately on snare and bass drum combined with a cymbal.

[4] Bass drum playing technique in which both feet are used alternately to achieve a very high tempo.