1 Introduction

In recent years, countries all over the world have been challenged by different crises. Prominent examples from a European perspective are the financial crisis erupting in 2008, the impact of forced migration on European political systems (especially after 2015), the Covid-19 pandemic, natural catastrophes, and the war in Ukraine. One concept that is helpful in crisis situations is resilience. In this study, we focus on social resilience of communities as well as on actors from society which respond spontaneously and in a self-organized manner to a crisis. We refer to such actors as bottom-up initiatives (BUIs). The main goal of this study is to understand, how civic BUIs contribute to community resilience.

It has become apparent that in addition to the traditional top-down approaches of policy makers and professional aid workers, so-called ‘grassroots’ or ‘bottom-up’ movements from the civilian population also play an important role in enabling resilient responses by society to adverse events (Fransen et al. 2021, 4–5). However, resilience should not only be understood as a reaction to something negative, because resilient societies are agile even in times without crisis and can foster innovation and bring new opportunities for societal transformation (Lukesch 2016, 303).

The first lockdowns due to the pandemic in early 2020 hit everyone overnight. At the same time, we immediately saw people supporting each other, for example, through neighborly help, by buying groceries for the elderly or through projects by students who tutored children through Zoom because schools were closed. The research specifically investigates BUIs that have emerged in Switzerland, Germany, and Austria in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. On this basis we seek to understand how these bottom-up actions relate to the concept of resilience.

We ran several expert interviews to learn more about bottom-up initiatives, community resilience and the appropriate method to measure impact for our purposes. We apply a qualitative approach to describe the relationships between BUIs and community resilience (see section 2).

We researched and catalogued over 70 BUIs from Switzerland, Germany, and Austria during the pandemic and other crises. We used indicators from the literature to describe the BUIs in our catalogue.

We conducted seven case studies with interviews to test our conceptual framework for community resilience in practice. Each case study focused on a particular bottom-up initiative, and we conducted semi-structured interviews with the initiators of each bottom-up initiative (see section 3).

2 Community Resilience and Bottom-Up Framework

Since the term resilience is used by several disciplines, ranging from psychology, economics, and engineering to crisis management, there are many ways to define resilience (Scharte and Thoma 2016, 124). Resilience can be achieved through bottom-up approaches, for example, bottom-up initiatives, as well as top-down approaches, such as central government crisis management. In this study, we focus specifically on community resilience.

2.1 Community resilience definition

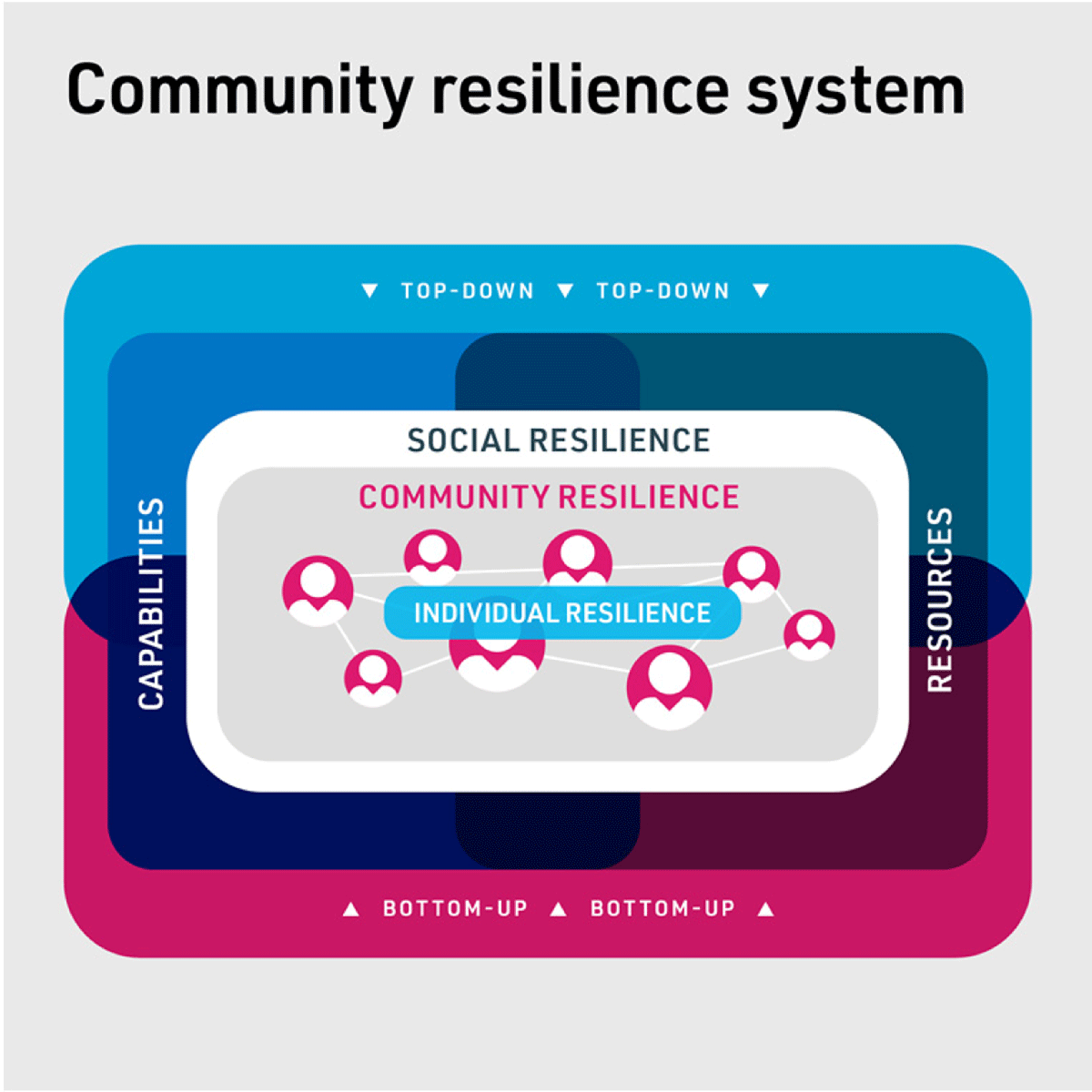

In recent years, an increasing number and diversity of actors have addressed the topic of community resilience. Next to purely scientific literature, a series of applied toolkits (e.g., Hegney et al. 2008; HUD 2022; Towe et al. 2015) focus on how to promote community resilience in practice. Figure 1 illustrates how many different concepts overlap and how resilience can be examined from a variety of perspectives.

Figure 1

Community resilience system (own figure).

To gain an understanding of how civil society initiatives influence resilience, we need to define the level at which we investigate social resilience. Existing literature captures different levels of social resilience: individual, family, tribe or clan, locality or neighborhood, community, regions or nations, social associations (clubs, faith), organization (firms, etc.), and systems, such as environmental systems or economic systems (Buckle 2006, 93). Because local communities are viewed as an essential frontline in preparing for and dealing with the consequences of a disaster, we concentrate on the community level and, consequently, on community resilience (Kwok et al. 2018, 3). The implemented definition of community in this study seems to capture local impact of a crisis accurate. In addition, the way we understand BUIs justifies the level community even further (view section 2.2). Community stands (1) for a group of people connected by the place where they move, live or to which they feel connected and (2) for the space of action of an individual detached from the geographical space of movement, although these spaces often overlap (Lukesch 2016, 308–10; Rapaport et al. 2018, 471). An example of a community is therefore a city, a neighborhood, or a village, in which people live and to which they feel connected, but also a profession, hobby, or other activity in which people are engaged.

In this study, we focus on the manifestation of community resilience, meaning that we determine which factors are essential for a system to be able to react resiliently (Huber et al. 2017, 98–99). We are specifically interested in what capabilities are necessary for communities to react resiliently to crises. Furthermore, we examine which circumstances lead to innovative solutions and how capabilities that have emerged during a crisis can be adaptively integrated into a new normality (Huber et al. 2017, 99–100).

In summary, we developed the following definition of community resilience based on Berkes and Ross (2013), which also considers the other concepts described above:

“Community resilience is the capability of a community to resist and potentially thrive in a period of pressure, disturbance, or change with solutions, actions, or development that are sustainable for the community”.

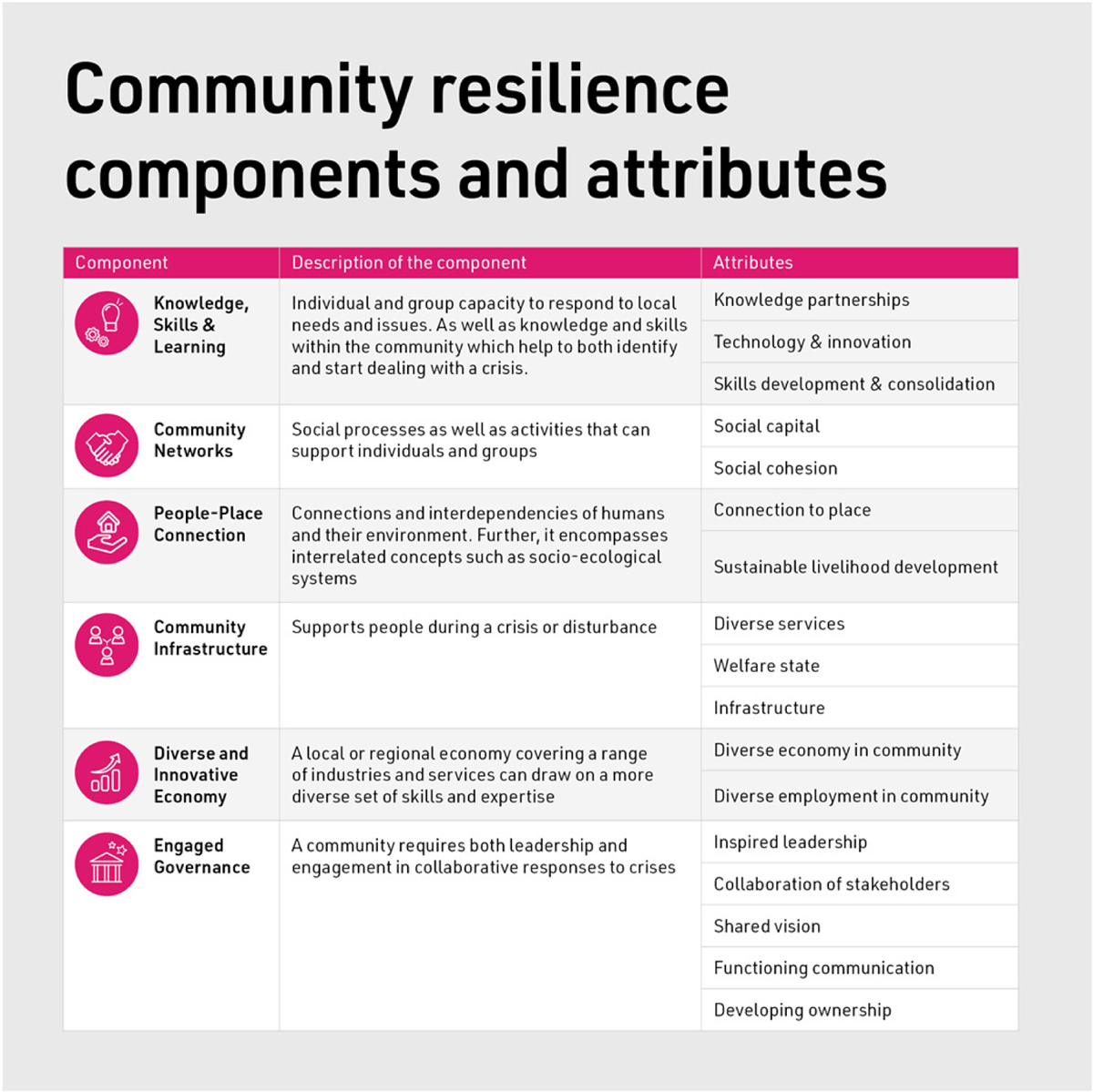

2.1.1 Community resilience components and competencies

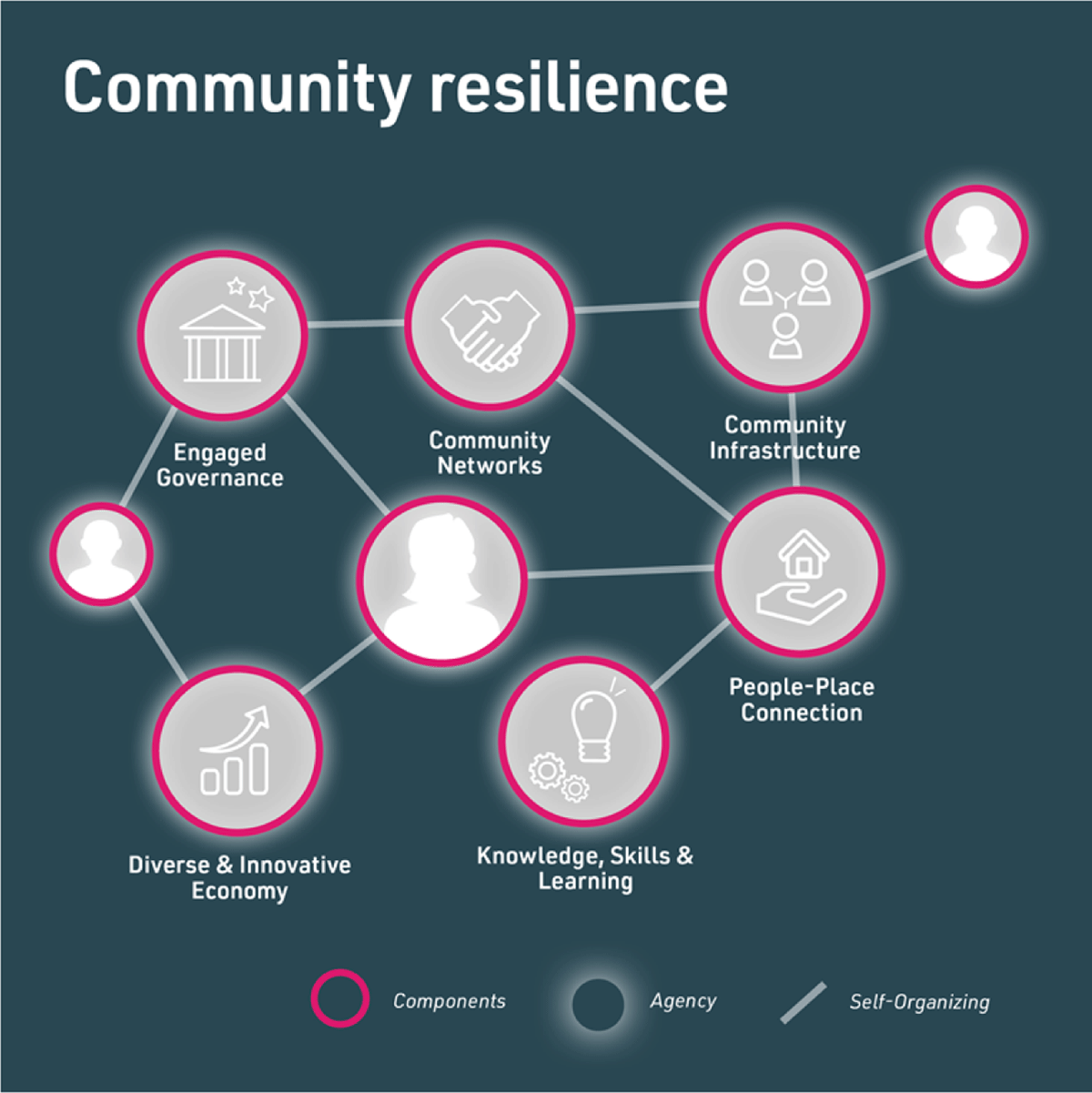

We now examine the components and competencies that make up community resilience, following the establishment of its theoretical significance. Maclean et al. (2014) describe six relevant components (Knowledge, Skills & Learning; Community Networks; People-Place Connection; Community Infrastructure; Diverse and Innovative Economy; and Engaged Governance) for community resilience (see the named icons in Figure 2).

Figure 2

Community resilience framework (own figure based on Berkes and Ross 2013; Maclean et al. 2014).

However, to activate a resilient response, two other competencies are required. Berkes and Ross (2013) concentrate on two core competencies: Agency and Self-Organizing (see Appendix A for the description of components). The six components are therefore relevant conditions for a community to respond resiliently to a crisis and are activated through Agency and Self-Organizing, making the latter necessary conditions.

Agency, represented by the white shimmer around the icons, describes the sense of responsibility for an issue and thus the ability to see the need for action in a community. Self-organizing describes the ability to react independently and in a self-organized way. It’s represented by the connecting lines that bring people and components together to enable a resilient response. As communities are quite heterogeneous, these six components have been extracted by the cited authors from numerous case studies and refer to key structures that are present in all communities (Berkes and Ross 2013; Maclean et al. 2014).

2.2 Bottom-up initiatives

BUIs can be defined as community-based civic action groups organized by private households (Seebauer et al. 2019, 101). Other definitions focus on whether BUIs are started and managed by civil society actors or individuals, whether they have received public money, or whether they are profit-oriented. An important common characteristic of such initiatives in all definitions is that the overall objective serves the community (The TESS Project 2017, 6).

In compiling sources on bottom-up initiatives, we noticed the following clear pattern: At the beginning of a crisis, civic engagement increases rapidly, peaks and then declines over time. This can be explained by the fact that initially the pressure of suffering, and therefore the level of engagement, is highest. After a while, and especially in the countries we examined, top-down institutions usually take over or smaller groups evolve into larger structures and themselves institutionalize. As a result, many of the initiatives are very short-lived. Although not the focus of this report, this finding led to the identification of different phases that an initiative may run through in its development. Similar phases and critical development steps for bottom-up or grassroots initiatives have also been identified in other contexts, for example, in literature focused on grassroots innovation in the environmental movement (Bergman et al. 2010; Moser et al. 2018; Ornetzeder and Rohracher 2013; Seyfang and Haxeltine 2012). There may also be links between the emergence of BUIs and existing theories in the transformation literature, for example, for strategic niche management (Kemp et al. 1998; Seyfang and Haxeltine 2012). Although there is little literature linking the concepts to crisis management, we see many parallels.

We combine these definitions in our project and further include local businesses (business that is active in the respective community. E.g., a grocery shop etc.), because our case studies provide examples of businesses supporting their communities during a crisis beyond their usual operations. Thus, we employ the following definition of BUIs in this study:

“Bottom-up initiatives are community-based and participatory civic action groups initiated and organized by individuals in a community, which may act either as private persons, organizations, or local businesses. Bottom-up initiatives may or may not have received public funding and may be non-profit- or profit-oriented but the overall objective of the bottom-up initiative is to serve the community”.

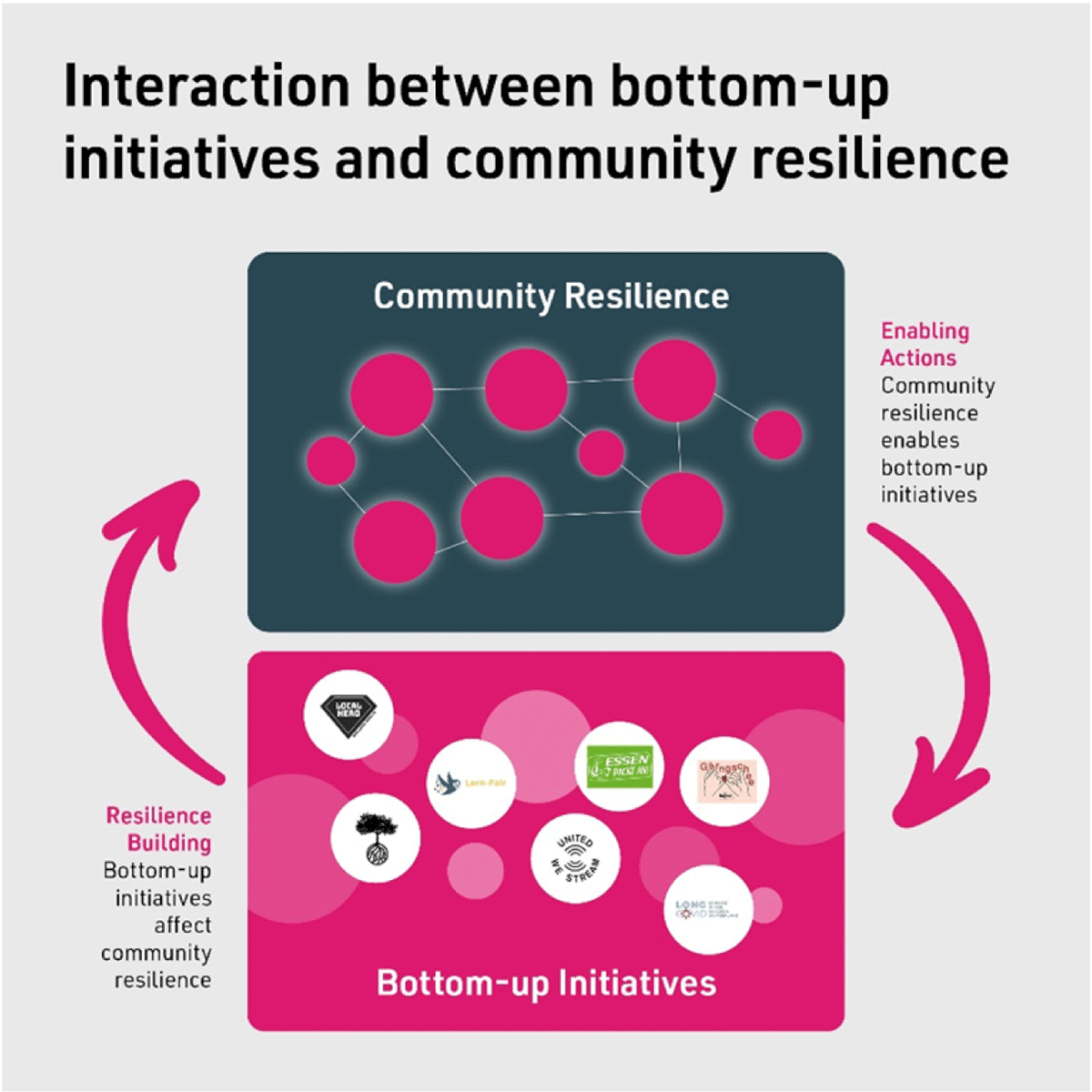

2.3 Linking bottom-up initiatives and community resilience

We have introduced the concept of community resilience and defined BUIs in the study. The main goal was to understand how BUIs affect community resilience. Yet, our analysis soon showed that this effect needs to be examined from two perspectives: Resilience Building and Enabling Actions. Resilience Building explores the potential influence of BUIs on community resilience, while Enabling Actions assumes that the emergence of BUIs is facilitated by existing community capabilities (Fransen et al., 2021, 4-5). This interactive relationship is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Interaction between bottom-up initiatives and community resilience (own figure).

Following the first perspective, Resilience Building, we can assess whether a bottom-up initiative reinforced a community and possibly increased resilience in the community during a crisis. For example, when the bottom-up initiative Local Hero (For more information on each initiative, see full report in https://www.risiko-dialog.ch/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Bottom-up-Resilience_StiftungRisikoDialog.pdf) developed a webpage to foster local gastronomy during the pandemic, we can argue that it helped reinforce community resilience. The webpage helped local businesses to sell their products and so reduced the negative effect of the crisis on the local economy. Following this perspective, Local Hero helped local restaurants to stay in business and might have had a positive influence on several components of community resilience such as People-Place Connection, Diverse and Innovative Economy, and Engaged Governance.

The second perspective, Enabling Action, describes the relationship between BUIs and community resilience from the opposite direction. The emergence of BUIs might well be a predictor for already existing community resilience. Only a resilient community should be able to produce bottom-up initiatives. Therefore, it is interesting to identify which components of the community resilience framework encouraged the emergence of a bottom-up initiative. In the case study mentioned above, we find that the emergence of Local Hero was made possible by a set of community resilience components: Knowledge, Skills, & Learning, Community Network and People-Place Connections.

In summary, the applied community resilience framework seems to capture the complex relationship between BUIs and community resilience. It is important to understand how components of community resilience Enable Action through the emergence of bottom-up initiatives. At the same time, it is crucial to be able to analyze whether a new bottom-up initiative further promotes Resilience Building in a community. The latter perspective is particularly important because all the BUIs analyzed in this study were not directly aimed at promoting community resilience, but rather sought to address a specific problem within their community during a crisis.

3 Case Study Analysis

After this rather theoretical and abstract part, we would now like to apply the presented concepts to real cases. The pandemic allowed us to identify numerous BUIs which were active very recently. Initiatives formed during crises such as floods help to ensure the applicability of our work to a broad range of topics. By applying the theoretical framework to a diverse set of case studies, we demonstrate how BUIs and community resilience are related.

3.1 Systematic selection process for bottom-up initiatives

Before the search of bottom initiatives, we conducted interviews with professionals from different fields (e.g., disaster managers, community organizers) to find as many sources as possible. Based on these sources, we started an internet and media search to compile our sample of initiatives. We decided to focus on and document 17 indicators to characterize the identified bottom-up initiatives. The inspiration for the indicators describing the initiatives stems from studies by Jaeger-Erben et al. (2015) and Fransen et al. (2021).

At first the search was quite difficult as the online footprint often only consisted of a Facebook group or a mention on a website. Interestingly, there was also very little coverage of such initiatives in the media during the pandemic. In the end, we identified well over 70 BUIs focusing on a range of issues (for full report see https://www.risiko-dialog.ch/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Bottom-up-Resilience_StiftungRisikoDialog.pdf). We opted to choose our sample based on diversity, rather than creating a representative sample, and are aware that our sample comes with certain biases due to the method and timing of the search.

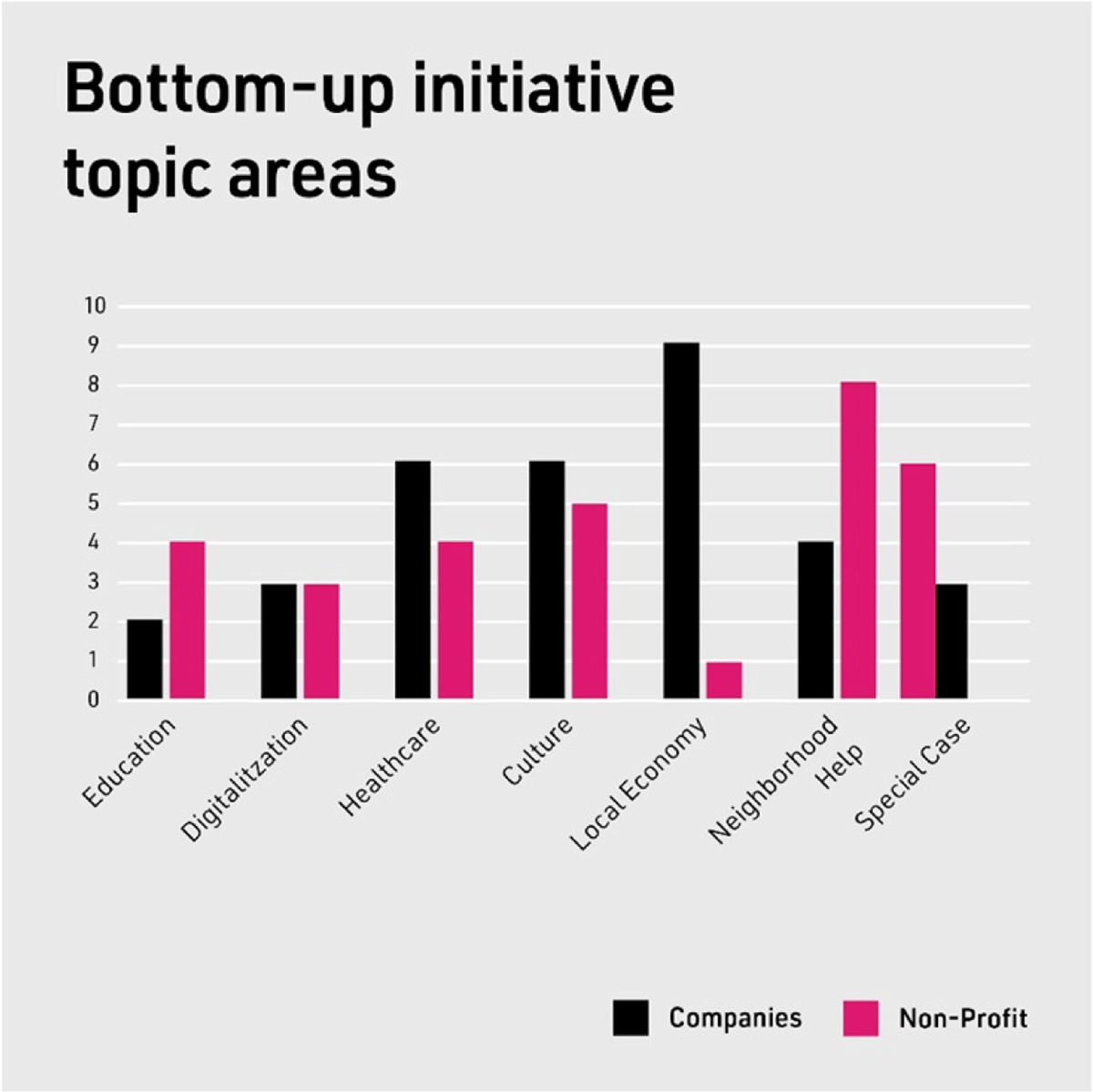

Since the identified initiatives had diverse goals, we tried to divide them into topic areas. We were surprised about the great diversity of the initiatives, especially because this diversity was seldom portrayed in the media such as public news stations (radio and television) or newspapers. We grouped the identified BUIs into seven topic areas as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Bottom-up initiative topic areas (own figure).

We selected seven of the over 70 identified BUIs for more in-depth case studies. Case studies were selected to represent all topic areas and based on diversity. The selected BUIs are briefly described in the full report (see https://www.risiko-dialog.ch/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Bottom-up-Resilience_StiftungRisikoDialog.pdf).

3.2 From method to practice: applying the Framework

Each case study consists of a questionnaire as well as a semi-structured interview. Prior to the semi-structured interview, the person representing the bottom-up initiative and the project team, acting as an expert panel, completed a questionnaire on the impact of the initiative on the components and attributes of community resilience (see Figure 2).

In a first step, we formulated a question for each component to determine whether the bottom-up initiative influenced community resilience (view section 2.3 in Figure 3 the concept Resilience Building). Second, we formulated a question for each attribute to understand what helped the emergence of the bottom-up initiative (view section 2.3 in Figure 3 the concept Enabling Resilience). Since we were dealing with very different individuals with different educational backgrounds, we decided to use a 1-to-5-point response scale. We then compared the self-assessment and expert assessment regarding community resilience to understand whether the applied community resilience framework is valid. Further questions about the interrelationship between BUIs and community resilience were discussed during a one-hour semi-structured interview.

3.3 Bottom-up initiatives strengthen community resilience (Resilience Building)

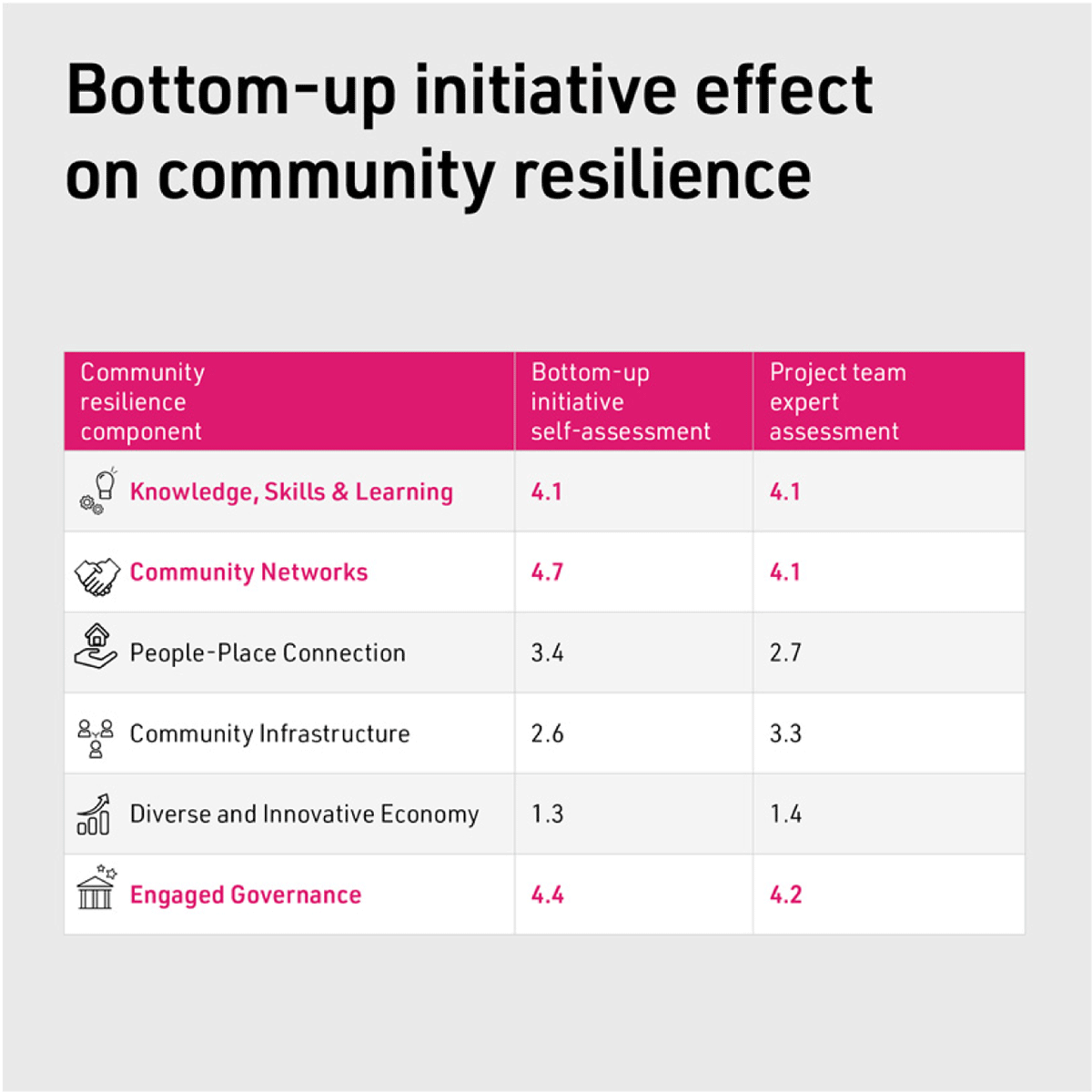

In this section, we discuss the results of the initial question of the study, namely, BUIs strengthen community resilience (see Table 1).

Table 1

Bottom-up initiative effect on community resilience.

The numbers represent averages of the responses to the questionnaire and range from 1 (small or no positive influence) to 5 (large positive influence). We present both the self-assessment summary and the expert assessment aggregated (were done independently) from the seven case studies in Appendix B. Right away we see that the community resilience components Knowledge, Skills, & Learning, Community Networks, and Engaged Governance seemed to be strongly influenced by the BUIs in the analyzed case studies. The aggregate value is 4 or higher for all three components.

The effect on Knowledge, Skills, & Learning can be explained by the personal growth of the people involved in the initiatives (initiators as well as volunteers and other affected people) as well as the development of communication structures that are always needed and help to strengthen this component. The effect on Community Networks is explained by the more intensive contact with other organizations; the construction, growth, or welding together of the community; and the growth of networks within and beyond the community. Finally, the effect on Engaged Governance can be explained by the role model function of the initiators and volunteers for other individuals in the community. In the interviews, people often described how their actions during the crisis had an inspiring and empowering influence on their personal network. People-Place Connection does not seem to have been a key component, primarily because many of the analyzed pandemic-related BUIs were mostly digitally active, meaning that the immediate link to the near neighborhood was less important than for initiatives started during other crises. Still, the component was important in some cases, as the Local Hero initiative shows and reflected in the average value of 3.4. The effect of the BUIs on the component Community Infrastructure showed less relevance in our analysis. Even though several initiatives created new infrastructure on a small scale (primarily assorted services, but also communication infrastructure and transport infrastructure through websites and online networks), these effects were all viewed as being small.

The impact on Diverse and Innovative Economy was also estimated to be rather low and it is not possible to make an argument that the specific BUIs analyzed in this project influenced it. Some BUIs tried to support local businesses, but these efforts were often selective and the BUIs we analyzed in the case studies focused on a specific sector instead of the economy.

Overall, the accordance rate between the assessments of the project team and the bottom-up initiative self-assessment was around 75–80%. This shows the applicability of the community resilience framework for practical analysis.

Also for these results holds the general caveat that answers can be biased dependent on background and context of the responding person.

3.4 Bottom-up initiatives indicate existing community resilience (Enabling Resilience)

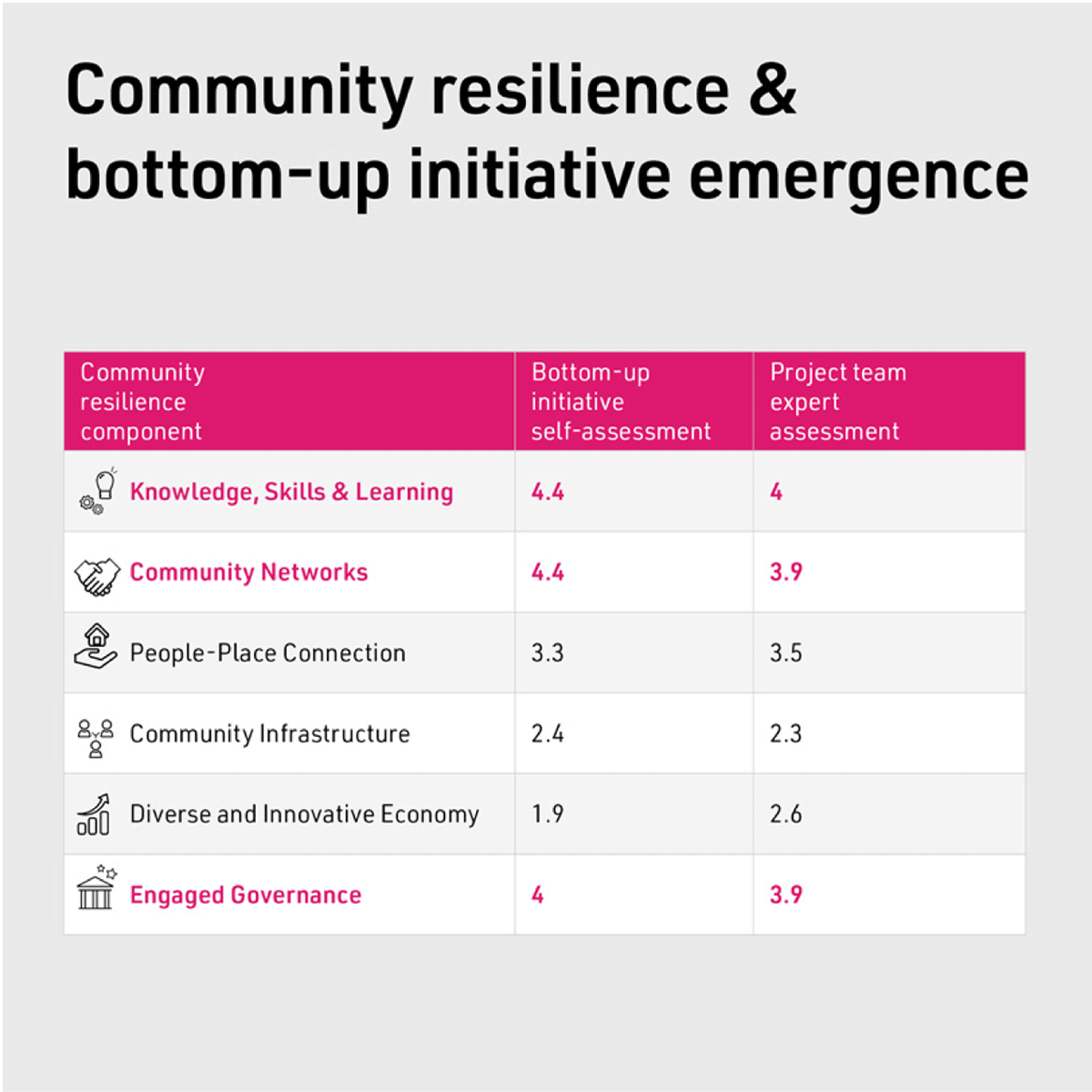

Let us turn our attention to the second part of the interaction and analyze which community resilience components were important for BUIs to emerge.

Table 2 presents the estimated level of importance of the community resilience components for the emergence of the respective bottom-up initiative. As before, the components Knowledge, Skills, & Learning, Community Networks and Engaged Governance of the community resilience framework seem to be most important.

Table 2

Community resilience & bottom-up initiative emergence.

Knowledge, Skills & Learning component shows, that the emergence of a bottom-up initiative always builds on the existing know-how of the individuals within the community. Diverse knowledge is the foundation for an agile and innovative reaction.

Community Networks was also a relevant component for BUIs to emerge. Especially the attribute Social Capital is essential for the emergence of bottom-up initiatives, particularly at the beginning but also when the initiatives grow and eventually institutionalize. Most of the interviewed initiators emphasize the importance of their personal friendships, acquaintances, and professional network. The connection of people to the space they live in (People-Place Connection) was also central to some of the initiatives. However, since many of the initiatives functioned online, the importance of this component varied greatly between initiatives.

The components Community Infrastructure and Diverse and Innovative Economy were often not considered to be relevant by bottom-up initiative representatives, which we found surprising. The interviews indicated that this may be to some part related to the wording in the questionnaire. Yet inquiries during the interviews showed that both components were relevant for the BUIs to come into being in the first place. It seems that the relevance of the components Community Infrastructure and Diverse and Innovative Economy were taken for granted by the interviewed bottom-up initiative representatives. As the conversations have shown, partial aspects of the two components were central to the emergence of most of the initiatives. In conversation with Glocal Roots (see full report in https://www.risiko-dialog.ch/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Bottom-up-Resilience_StiftungRisikoDialog.pdf), we were able to further elaborate on this phenomenon. We concluded that building resilience also depends on the context of a community. Glocal Roots accompanies projects in both Athens and Zurich with the goal of empowering people with refugee backgrounds. However, depending on the city where the activities take place, their work varies greatly, in part because building resilience requires that basic needs are met.

Comparisons with BUIs active in other crises confirm our hypothesis that the relevance of the two components Community Infrastructure and Diverse and Innovative Economy was underestimated by the interviewees in the case of the pandemic and the countries of interest. The analyzed countries have very strong manifestations of these components. It seems that these components were therefore taken for granted. Following this, we argue that the context (cultural or economic) of a community is central to the analysis of community resilience.

All interviewed initiators emphasized the importance of communication for the emergence of bottom-up initiatives. It is crucial for a bottom-up initiative to communicate to media and gain much-needed public attention. The communication is also important internally for the organization of the initiatives. These capabilities are all covered by attributes of Engaged Governance.

3.5 Case study conclusion: building on partnerships and existing connections

Following the results from the case studies, we conclude that BUIs can have a positive effect on community resilience. We argue that this effect could apply to other cases and situations as well, and because we focused on different crises, we hypothesize that BUIs in general might have a positive impact on community resilience.

The case studies further confirm that BUIs can react quickly and agilely in a crisis. Due to their relative independence from organizational as well as political constraints, BUIs have the potential to react faster than top-down engagement (The TESS Project 2017, 2).

A functioning relationship between top-down and bottom-up action is critical for an overall efficient reaction during a crisis. This is also reflected in the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030, which indicates that disaster risk reduction requires the commitment and partnership of society as a whole (Brebbia et al. 2018). This is only possible if top-down approaches, such as government initiatives and programs, and bottom-up action, reacting to a crisis, work together, communicate effectively, and know as well as respect each other’s strengths. Relying solely on top-down approaches is known to undermine local capacities and knowledge (Brebbia et al. 2018).

While discussing the possible effect of the bottom-up initiatives, the interviewees explained that, especially in the beginning, they could not focus on impact measurement because they had to invest most of their energy and time in achieving the goals they had set. Nevertheless, effects can be measured by quantitative measures (money collected in fundraising campaigns, number of people who signed up on a neighborhood help platform) or by qualitative feedback (feedback forms, direct feedback from people affected). Some of these feedback mechanisms were already employed by BUIs such as United We Stream (see full report in https://www.risiko-dialog.ch/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Bottom-up-Resilience_StiftungRisikoDialog.pdf). Positive experiences and the feeling of having an impact were also especially important for the bottom-up initiatives. This reaffirms the importance of motivation, confirmation, and success for the persistence of a bottom-up initiative.

Agency and Self-Organizing are key competencies which are particularly significant in the analysis of BUIs because the initiators react out of their own motivation. The examined cases revealed that most of the initiators of BUIs had already gained experience in associations or other social commitments before the crisis. The interviewees repeatedly stressed the relevance of positive feedback for bottom-up initiatives. Especially in challenging times, this is central to the motivation of the people involved.

It is very exciting to see how concordant the postulated community resilience components and competencies from our conceptual framework were with the content of the conversations about the initiatives in the case studies. Several interview partners even confirmed that the questionnaire based on the framework helped them to rethink their own impact logic. Important learnings made by BUIs are seldom documented and remain very much within the respective specialist areas or with involved individuals. This requires a renewed interdisciplinary exchange when the next problem or crisis arises. Thus, networks and relationships are extremely important for fostering community resilience trough bottom-up action.

4 Discussion and Conclusion

The goal of the study is to understand how civic bottom-up initiatives impact community resilience. Therefore, we focus on social resilience, specifically on the resilience of communities, as well as actors from society who respond spontaneously and in a self-organized manner to a crisis. To build resilience, an integrative perspective needs to be applied, meaning that all actors in society – not only the government or large aid organizations, but also actors such as BUIs – must be involved. While BUIs cannot and should not replace top-down approaches, their integration into existing crisis management is essential. The two approaches should be complementary to each other in the event of a crisis.

We summarize the findings of this study in three main results:

We conclude that it is essential to also involve the population of a community in crisis management and that they need to be part of the solution. The large number of BUIs emerging as a response to the Covid-19 pandemic proved this thesis and showed that people are willing to come together as a community and support each other in a crisis. Our classification of BUIs in six distinct topic areas (view section 3.1) clearly shows how diverse and extensive civic engagement in a crisis can be.

We have successfully identified important components (People-Place Connection; Engaged Governance; Community Networks; Knowledge, Skills, & Learning; Diverse & Innovative Economy; and Community Infrastructure) as well as competencies (Agency and Self-Organizing) of community resilience. The analysis of the cases shows that the applied community resilience framework can meaningfully explain the effect of BUIs on community resilience (see sections 3.3–3.4).

The results of the case studies strongly indicate that community resilience can be strengthened through BUIs (see section 3.5). It became clear during the analysis that the relationship between BUIs and community resilience is not one-sided and needs to be viewed as an interaction: BUIs can strengthen community resilience (first perspective), while the emergence of BUIs is also an indication of a resilient community (second perspective). We identified the community resilience components Knowledge, Skills, & Learning, Community Networks, and Engaged Governance as being most relevant for both perspectives, applying two separate questionnaires, one for each perspective, in the case studies.

In addition to the main results, the study identified further relevant questions that should be addressed and elaborated in the future:

This study employed a qualitative approach – it’s important to complement it with quantitative indicators to measure community resilience. The analysis of community resilience could strongly benefit from the use of a combined methodological approach.

A better understanding of the impact of different cultural or economic contexts on the community resilience framework (e.g., available resources, political systems, and experience with crises and discrimination) is essential for the further application of the framework. This might also include the analysis of sociodemographic characteristics of communities.

The case studies have shown that BUIs go through various phases. E.g., initiatives experience different challenges in the beginning or when they possibly scale into a larger organization. This could be an important topic for further study, especially regarding the future support of bottom-up action.

It’s relevant to investigate the effect of societal transformation on resilience – what will happen to resilience when the whole society is transformed in its foundations?

Overall, the goal should be to establish a strong resilience culture. This way we hope to sustainably overcome future crises and to continuously develop and learn. We establish the necessary three approaches to increase community resilience through bottom-up activities and to increase social resilience in general based on the findings of the study:

Understanding resilience: to establish a culture of resilience, conceptual agreements must be reached. Government agencies and specialist communities should engage in bottom-up activities to comprehend social and community resilience. Next steps include reflecting on the resilience concept with stakeholders, creating a measurement instrument, investigating the relationship between bottom-up and top-down approaches, and analyzing aspects like polarization and lessons from other countries.

Shaping resilience: establishing basic conditions for resilience requires an integrative approach involving relevant stakeholders. Activities and projects should encourage networking among resilience communities, work closely with regional networks and activists, and develop general conditions collectively.

Fostering resilience skills: strengthening resilience skills within society is crucial for sustainable crisis management and growth. Specific support is needed to promote resilience skills among regional multipliers. Ideas include better infrastructures for bottom-up activities, integrating resilience projects into existing community development efforts, incorporating resilience culture in education, rewarding multipliers for exceptional contributions, and providing support for local initiatives.

In summary, the results of this study confirm the importance of social resilience through bottom-up actions for the sustainable management of crises in a society. This focus on bottom-up resilience is essential to complement existing top-down approaches. In view of current and future crises, it is of great importance to explore, make visible and actively promote the strengthening of social resilience through bottom-up activities and in general. This way, it is possible to learn to deal efficiently with crises and emerge even stronger from crisis situations.

Appendices

Appendix

Appendix A: Community Resilience Components and Attributes

(Own table on Berkes & Ross 2013 and Maclean et al. 2014)

Community-Resilienz durch Bottom-Up-Initiativen

Krisen sind Teil unserer Realität, und wir müssen lernen, sie nicht nur zu bewältigen, sondern gestärkt daraus hervorzugehen. Resilienz ist ein vielversprechendes Konzept zur Bewältigung von Krisen.

In diesem Bericht konzentrieren wir uns auf die soziale Resilienz von Gemeinschaften sowie auf Bottom-up-Initiativen (BUIs), die spontan und selbstorganisiert auf eine Krise in der Schweiz, Deutschland und Österreich reagieren. Wir versuchen zu verstehen, wie BUIs mit dem Konzept der Resilienz zusammenhängen.

Um einen umfassenden konzeptionellen Rahmen zu entwickeln, recherchierten wir über 70 BUIs, wobei wir für unsere Fallstudie davon sieben BUIs auswählten.

Die Analyse der BUIs auf ihre Resilienzfähigkeit zeigte, dass die Interaktion zwischen Resilienz und BUI aus zwei verschiedenen Perspektiven analysiert werden muss: Resilience Building zeigt die möglichen Auswirkungen von BUIs auf die Resilienz der Gemeinschaft, und Enabling Actions beschreibt die Tatsache, dass das spontane Entstehen von BUIs auf den vorhandenen Fähigkeiten innerhalb der Gemeinschaft beruht.

Insgesamt kommen wir zu dem Schluss, dass sich Bottom-up-Initiativen positiv auf die Widerstandsfähigkeit von Gemeinschaften auswirken. Wir haben wichtige Komponente (People-Place Connection, Engaged Governance, Community Networks, Knowledge, Skills, & Learning, Diverse & Innovative Economy, and Community Infrastructure) und Kompetenzen (Agency and Self-Organizing) identifiziert, die für eine resiliente Gemeinschaftsreaktion relevant sind.

Schließlich haben wir drei Empfehlungen formuliert, um die Resilienz der Gemeinschaft zu erhöhen und eine resiliente Kultur zu schaffen.

Schlüsselwörter: Soziale Resilienz, Bottom-Up, Krise, Bewältigung, Gemeinschaftsentwicklung

Résilience Ascendante: Comment les Initiatives Bottom-Up Contribuent à la Résilience des Communautés

Les crises font partie de notre réalité et nous devons apprendre non seulement à les surmonter, mais aussi à en sortir plus forts. La résilience est un concept prometteur pour faire face aux crises.

Dans ce rapport, nous nous concentrons sur la résilience sociale des communautés ainsi que sur les Initiatives Bottom-up (BUI) qui réagissent spontanément et de manière autoorganisée à une crise en Suisse, en Allemagne et en Autriche. Nous essayons de comprendre comment les BUI sont liées au concept de résilience.

Afin de développer un cadre conceptuel complet, nous avons effectué des recherches sur plus de 70 BUI, dont sept ont été sélectionnées pour notre étude de cas.

L’analyse de la capacité de résilience des BUI a montré que l’interaction entre la résilience et les BUI doit être analysée sous deux angles différents : Resilience Building montre l’impact potentiel des BUI sur la résilience de la communauté, et Enabling Actions décrit le fait que l’émergence spontanée des BUI repose sur les capacités existantes au sein de la communauté.

Dans l’ensemble, nous concluons que les initiatives ascendantes ont un impact positif sur la résilience des communautés. Nous avons identifié des composantes (People-Place Connection, Engaged Governance, Community Networks, Knowledge, Skills, & Learn-ing, Diverse & Innovative Economy, and Community Infrastructure) et des compétences importantes (Agency and Self-Organizing) qui sont pertinentes pour une réponse communautaire résiliente.

Enfin, nous avons formulé trois recommandations afin d’augmenter la résilience de la communauté et de créer une culture résiliente.

Mots clés: Résilience sociale, bottom-up, crise, faire face, développement communautaire

Funding Information

This project received funding from the Swiss Re Foundation.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author Contributions

K. A. Arvanitis and M. Holenstein share first authorship and equally contributed to the commentary.