1 Overview

Repository location

Zenodo: 10.5281/zenodo.16761169; GitHub: https://github.com/epfl-timemachine/venice-1808-landregister. The GitHub URL links to a set of code notebook, CSV, and JSON formatted files corresponding to the full pipeline of data generation and its final output, respectively.

Context

The Venetian Napoleonic cadastre, produced between 1807 and 1811 following a specific decree of the Regno Italico established by Napoleon Bonaparte, marked a pivotal shift toward modern, data-driven land administration Clergeot (2007). It introduced standardized cartographic methods and detailed fiscal records to support new taxation policies, including rental income taxes and large-scale sales of state properties.

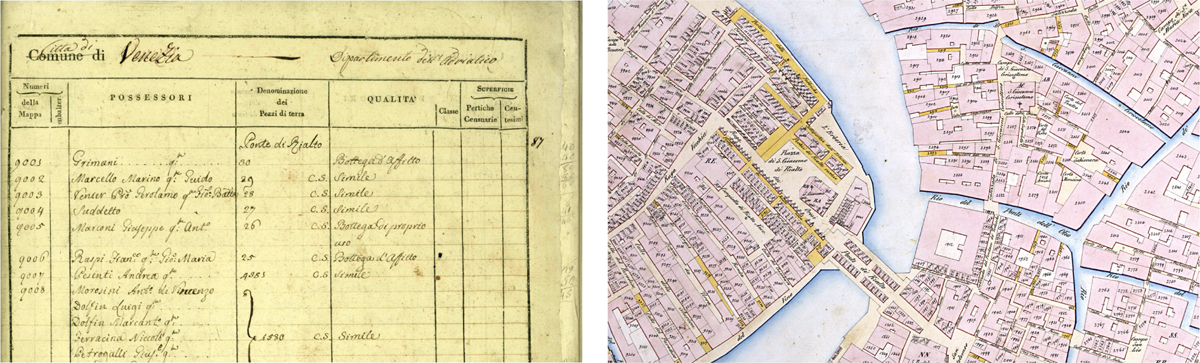

The Napoleonic cadastre was the first survey to apply standardized geometric methods across French-admin -istered territories Kain and Baigent (1992). The Venetian cadastral system adopted three fundamental elements from the structure of the États de sections registers: the cadastral map (with numbered parcels), the registers (which provided a description of each parcel), and the matrix (which linked the parcels to their respective owners). Compared to the system established in France, the Venetian cadastre retained parcel identifiers, the names of the owners (without reference to their professions), the designation of the parcel’ function (qualità), and the estimated area expressed in perches, which served as a basis for the calculation of the applicable tax. Although this last field remains empty for the city of Venice, it does contain values for the neighboring islands and the mainland. At its core were the Sommarioni land registers, which recorded ownership, dimensions, and parcel use (Figure 1). This dataset focuses on the registers of Venice’s six administrative districts.

Figure 1

The Sommarioni Land Registers page detail, [Venice State Archive] (on left) and Plate detail (on right) original documents samples.

The Sommarioni were initially transcribed during the Venice Time Machine project and the READ European project (Horizon 2020, No. 674943) Mühlberger et al. (2019); Oliveira et al. (2019), aimed at training algorithms to read Venetian cursive. After semi-automated transcription, the data were fully manually verified, standardized, and interpreted in the context of the Parcels of Venice (SNSF) project. The cadastral survey comprises 27 plates created according to official specifications. These maps were digitized using computational extraction and manually verified Petitpierre (2020). After georeferencing them by superimposing them on the vectors available on OpenStreetMap and using the free QGis software and the WGS84 reference system, the geometries were vectorized and cleaned up. The georeferencing took into account the city’s historical landmarks, which have not undergone any changes since 1808. Bridges, canals, and riverbanks are less accurate. To correct misalignments, particularly at the joints between slabs, the vectors were rectified, resulting in slight shifts from their original positions.

The goal of extracting the Napoleonic cadastre of Venice is to obtain a reference dataset that supports the realignment of earlier cartographic layers. The city, as of 1808, had not yet experienced the major infrastructural transformations that began in the mid-19th century. The extracted dataset thus constitutes a foundational spatial record for historical analyses di Lenardo et al. (2021).

2 Method

The dataset results from a multistep pipeline. Original manuscript registers were first transcribed using semi-automated tools and then manually corrected. Owner names, kinship terms, and property functions were standardised to improve interoperability. A named-entity resolution protocol was developed to disambiguate references to the same individuals across parcels, generating a set of over 12,000 unique person entities. Spatial parcel geometries were extracted from historical maps, georeferenced to present-day basemaps, and cleaned for consistency.

Content The published dataset includes: Structured entries for over 20,000 parcels; Semantic categorization of over 60 distinct property functions; A table of disambiguated owner entities with kinship, titles, and metadata; A merge log documenting identity resolution steps; Georeferenced vector geometries of all cadastral parcels. Formats include JSON and CSV. A full codebase supporting transcription and processing is published in the GitHub repository: https://github.com/epfl-timemachine/venice-1808-landregister.

2.1 Transcription and Standardization of the Sommarioni Registers

The dataset derives from a faithful transcription of the 1808 Venetian Sommarioni registers, key cadastral records that document parcel ownership and usage. The transcription process retained the original textual structure and variability, preserving archival peculiarities such as relational descriptors, spelling inconsistencies, and shorthand references (e.g., suddetto/a). Owner descriptions often include familial links, patronymics, or legal statuses (e.g., “heirs of”, “widow of”), typically expressed with irregular syntax. These were transcribed without alteration, ensuring the historical integrity of the document, even where entries were incomplete or reliant on contextual inference. While no editorial intervention was made during transcription, a post-processing phase implemented rule-based standardization for analytical use.

A multistep normalization pipeline followed transcription to harmonize the data for computational analysis. Key expressions, including legal terms such as quondam (q.), goduta da, or di provenienza, were regularized, and typographic inconsistencies were corrected. The pipeline emphasized a dual-layer approach: preserving the original text and deriving enriched, normalized fields for semantic analysis and reuse. Special care was taken with ambiguous ownership mentions, placeholders (e.g., ignoto possessore), and recursive references. The standardization preserved linguistic nuances while making the data computationally tractable.

Mentions of individual owners were standardized by parsing names into structured person entities. This included surname capitalization (e.g., MOROSINI Luigi), repetition of surnames in multiname entries, and categorization of relational notes using typographic cues: parentheses for individual notes, brackets for collective notes, and nested punctuation for complex legal annotations. Patterns such as family collectives (e.g., “fratelli q. Andrea”) or institutional heirs (e.g., “Eredi del fu…”) were also systematically addressed. This process yielded over 21,000 initial person records, each corresponding to a distinct mention, later used in entity resolution and kinship modeling.

To handle the typological diversity of name expressions, a schema of owner patterns was developed. It included single and multiple individual entries, family-based entries, ownership collectives, and legal or fiscal entities. Each pattern was assigned transformation rules to ensure consistency and resolve ambiguity.

Ecclesiastical and Institutional Owners were especially complex, often appearing in succession chains due to Napoleonic expropriations. A dedicated pipeline addressed these entities, disaggregating compound entries and attributing ownership across time using fields like owner_standardised and old_entity_standardised. Expressions such as succeduta a, già posseduta, or di ragione were normalized to track transitions. Institutions were realigned with Wikidata identifiers to improve interoperability, and institutional types were classified according to secular/religious function, ownership role, and typology (e.g., convent, hospital, confraternity). This enriched classification aids in comparative studies of property redistribution under Napoleonic reforms.

Titles and professional roles embedded in owner entries—particularly ecclesiastical designations like parroco, arciprete, or secular roles such as dottor, cavaliere—were extracted and encoded separately. These attributes support analysis of ownership by profession or clerical rank and help disambiguate individuals with common names.

Finally, to accommodate the dense annotation found in the owner records, a system was implemented to encode the supplementary notes. Individual-specific comments are enclosed in parentheses, while collective notes for families are in parentheses. Legal or administrative clarifications embedded within entries (e.g. guardianship clauses) were presented in nested form using dashes within parentheses. This framework allows for nuanced yet consistent representation of rich textual metadata, enhancing the potential for linked data integration and network analysis.

2.2 Person Disambiguation and Merging Protocol

People sommarioni_dataset:metadata capture all uniquely identified individuals from the 1808 Sommarioni registers, enabling a structured analysis of ownership patterns and social relations. After name standardization, a merging protocol was implemented to disambiguate multiple mentions of the same individual across parcels. The challenge lies in distinguishing true duplicates from coincidental name repetitions in a dense historical context like Venice.

Each mention was first converted into a structured person object. The core disambiguation heuristic required exact matches on surname and given name, combined with at least one additional shared attribute—such as patronymics, kinship terms, or co-ownership with known relatives. A more permissive configuration, relying only on name matching, was tested and would yield 14,684 merges; however, the standard protocol retained a more conservative approach to maximize reliability and avoid false positives.

The final result of the disambiguation process produced 9,312 merges, which led to a total of 12,277 unique person entities across the data set. The majority of the merges (5,053) were based on a single shared attribute; 802 cases involved two shared traits and 2 instances were matched in three or more. All merges were recorded with structured justifications in a dedicated merge_log_dataset.json, ensuring full traceability and allowing verification.

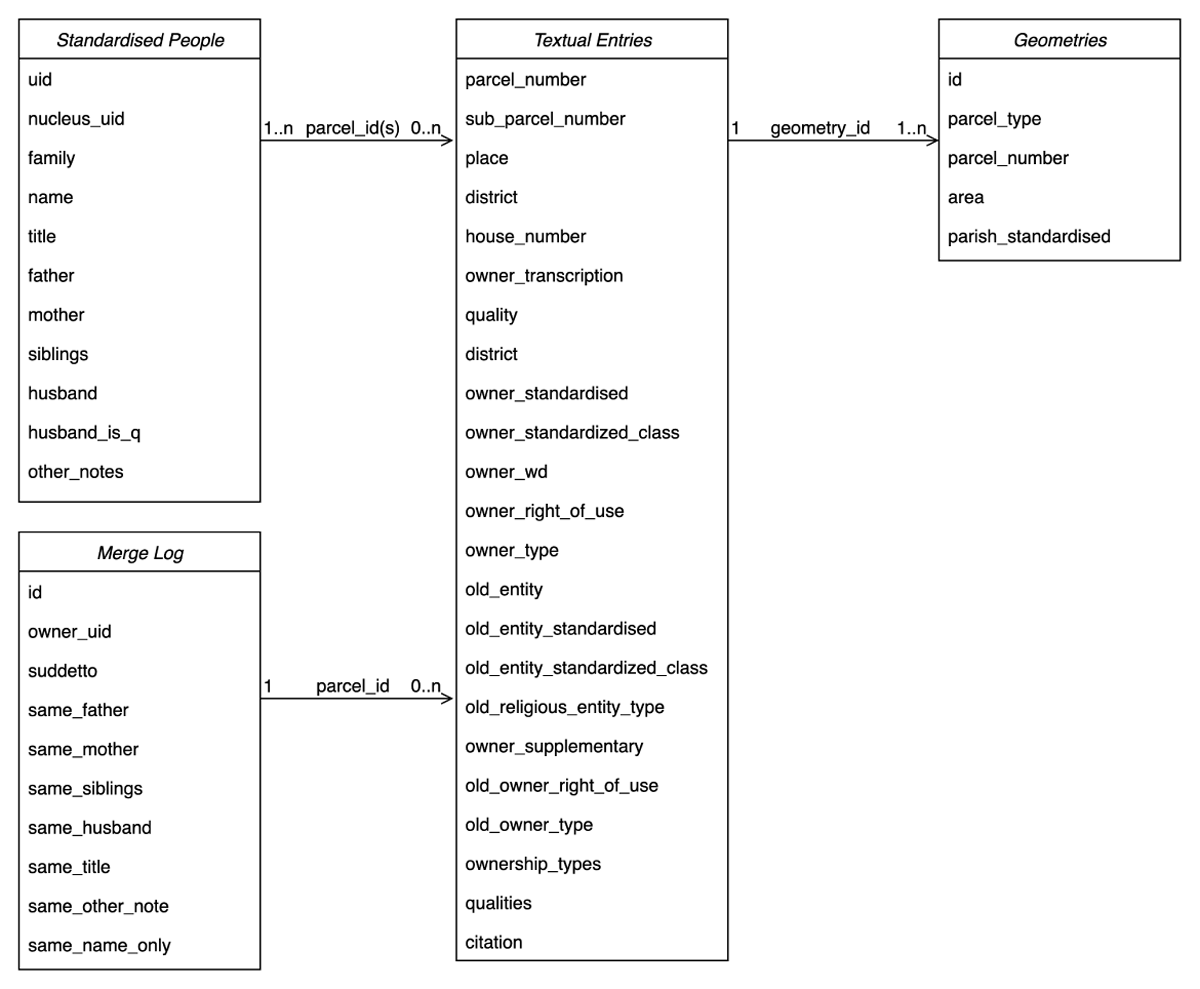

Figure 2 presents a Entity–Relationship (ER) diagram of the data set. It highlights how standardized individuals are linked to parcel entries and geometries, and how the merge log records the criteria used to disambiguate different mentions of the same person. This visual representation clarifies the overall organization of the dataset and supports its reuse.

Figure 2

Entity–Relationship (ER) diagram of the 1808 Sommarioni dataset. The diagram illustrates the three main components: Standardized People, which contains uniquely identified individuals after the disambiguation process; Textual Entries, which describe parcels and ownership information transcribed from the registers; and Geometries, which store the vectorized cadastral parcels. The Merge Log records the criteria applied to link multiple mentions of the same individual across parcels.

This merging strategy, tailored for the Venetian Napoleonic cadastre, is transferable to other pre-modern cadastral datasets where legal, relational, and naming conventions are similarly rich yet inconsistent. By combining rigorous name normalization with flexible rule-based heuristics, the framework supports both person-level entity resolution and larger-scale reconstruction of social, familial, and institutional networks grounded in land ownership.

Software Environment and Reproducibility

All processing and analysis was performed in Python (version 3.9.6). To ensure transparency and reproducibility, we report the main libraries and their versions: pandas 1.5.3, geopandas 1.0.1, numpy 1.26.4, tqdm 4.66.2, folium 0.16.0, pillow 10.2.0, Levenshtein 0.25.1, paramiko 3.4.0, as well as the langchain-core 0.3.72 and langchain-openai 0.3.28 packages. This combination of open-source libraries provided a robust environment for data cleaning, geospatial processing, and integration of textual and vectorized information. All scripts, notebooks, and installation requirements needed to reproduce the results are openly available in the project’s GitHub repository.

3 Dataset Description

Repository name

Venice 1808 Land Registers

Object name

Venice 1808 land registers — cadastral data — population enriched data

Format names and versions

JSON; GeoJSON are available here from Zenodo: 10.5281/zenodo.16761169; Jupyter notebooks and other data files, for data transformation and documentation, are available in the GitHub repository (https://github.com/epfl-timemachine/venice-1808-landregister).

GitHub repository description

The GitHub repository contains the full processing pipeline and data outputs accompanying the Venice 1808 Land Registers dataset. It includes:

venice_1808.landregister_geometries.geojson — vectorized cadastral parcel geometries from the 1808 Napoleonic survey.

venice_1808.landregister_textual_entries.json — transcribed and partially standardized Sommarioni entries linked to parcel geometries.

venice_1808.landregister_standardised_people.json — disambiguated person entities derived from ownership mentions.

venice_1808.landregister_aggregated_data.json — integrated dataset combining geometries, owners, and functions.

venice_1808.landregister_merge_log.json — detailed log of person-entity merges with heuristic criteria.

In addition to the main dataset files, we also provide complementary tables to facilitate use and reproducibility.

venice_1808.landregister_geometries.csv — contains the geometric layers of the cadastral parcels in a tabular format.

venice_1808.landregister_merge_log.csv — documents the data integration and merging process.

venice _1808.landregister_standardised_people.csv — provides a normalized list of individuals associated with parcels, allowing for direct linkage between registers and geometries.

Together, these files document the transcription, standardization, and disambiguation workflow, providing reusable source code, structured data, and traceability for the dataset.

Creation dates

Start date: 2018-01-09; End date: 2025-06-30

Dataset creators

Isabella di Lenardo (Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale Lausanne, Lausanne, Collège des Humanités, Time Machine Unit); Cédric Viaccoz (Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale Lausanne, Lausanne, Digital Humanities Institute, Time Machine Unit); Paul Guhennec (Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale Lausanne, Lausanne, Collège des Humanités, Digital Humanities Laboratory); Carlo Musso (Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale Lausanne, Lausanne, Collège des Humanités, Digital Humanities Laboratory); Raphaël Barman; Frédéric Kaplan (Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale Lausanne, Lausanne, Collège des Humanités, Digital Humanities Laboratory)

Language

Italian, Venetian dialect of the nineteenth century, English

License

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

Publication date

2025-08-10.

4 Reuse Potential

The 1808 Venice cadastral dataset constitutes a unique historical resource, bringing together detailed spatial data, transcribed archival text, and disambiguated personal information. Its structured nature and semantic richness support a broad range of potential reuses across both traditional historical disciplines and computational research in the digital humanities.

All processing and analysis were performed in Python (version 3.9.6). To ensure transparency and reproducibility, we report the main libraries and their versions: pandas 1.5.3, geopandas 1.0.1, numpy 1.26.4, tqdm 4.66.2, folium 0.16.0, pillow 10.2.0, Levenshtein 0.25.1, paramiko 3.4.0, as well as the langchain-core 0.3.72 and langchain-openai 0.3.28 packages. This combination of open-source libraries provided a robust environment for data cleaning, geospatial processing, and integration of textual and vectorized information.

4.1 Interdisciplinary Research Applications

The dataset can be reused in the field of urban and spatial history. Since it reconstructs Venice at a time immediately prior to the major urban transformations of the 19th century, the dataset serves as a reference model for the city’s pre-modern urban form. The availability of standardized geometries linked to cadastral parcels, together with data on owners and functions, allows for spatial analysis of building density, land use, and institutional versus private control over the urban landscape. In addition to spatial research, the dataset has considerable value for historical demography and the reconstruction of social networks.

In the data set, individuals can be traced across multiple properties, and family or co-ownership networks can be reconstructed. This person-based information can be useful for both qualitative research (e.g., prosopography) and quantitative studies using network models or relational statistics.

The data set also invites reuse in legal and institutional history, particularly in order to understand the implications of Napoleonic administrative reforms. Property entries contain rich semantic signals about transitional legal statuses, such as cases of confiscation, ecclesiastical use, or public ownership. From the perspective of digital humanities and linked data, numerous projects have focused on the vectorization of French land registries. Such datasets provide valuable resources for research from a variety of disciplinary perspectives. At the European level, several notable initiatives, though by no means exhaustive, have focused on the vectorization, publication, and open dissemination of cadastral data1 Viglino and Deseilligny (2003). the structure of the data set facilitates semantic interoperability with external data platforms. The use of JSON format, together with consistently applied field names and entity IDs, allows researchers to cross-reference these data with online geographical dictionaries and knowledge graphs (such as Wikidata).

4.2 Methodological Reusability

This dataset provides a reusable methodological model for processing historical sources. Its integration of accurate transcription, owner standardization, and rule-based disambiguation offers a framework that can be adapted to other cadastral registers or census records. The merging protocol, based on shared patronymics, familial roles, or repeated references, can be applied in contexts with similar naming patterns. Additionally, the annotation system preserves semantic ambiguity (e.g., quondam, suddetto) while structuring data for analysis, ensuring that historical nuance is retained during formalization. This dual focus on precision and interpretability supports historians working on named entity recognition or the modeling of uncertain textual references. The approach is both verifiable and extensible, making it valuable for future studies of early modern documentary corpora. Beyond scholarly reuse, the dataset can also be integrated into geographic web platforms (e.g., through GeoJSON or web-mapping libraries), enabling interactive visualisation of parcel boundaries and ownership patterns across time and space, as already exemplified by platforms such as TimeAtlas.2

Notes

[1] La Fabrique numérique du passé ; European Historic Towns Atlas ; Amsterdam Cadaster Vectors in 1832: “Amsterdam huurwaarden 1832”.

[2] https://timeatlas.eu — TimeAtlas is a geographic web platform developed within the Time Machine project that enables the exploration, aggregation, and enrichment of historical data through a spatial and temporal interface.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Raphaël Barman, Irene Bianchi and Sophia Oliveira for their preliminary work on these documents.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author Contributions

Isabella di Lenardo (Time Machine Unit, Digital Humanities Institute, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Lausanne): Conceptualisation, Methodology, Data curation, Validation, Funding acquisition, Project Administration, Supervision, Writing-original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Cédric Viaccoz (Time Machine Unit, Digital Humanities Institute, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Lausanne), Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Encoding, Software, Validation, Writing-original draft.

Paul Guhennec (Digital Humanities Laboratory, Digital Humanities Institute, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Lausanne), Methodology, Encoding.

Carlo Musso (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Lausanne), Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Encoding, Software, Validation.

Frédéric Kaplan (Digital Humanities Laboratory, Digital Humanities Institute, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Lausanne), Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project Administration, Supervision.