1. Introduction

Open-Air museums (OAms) have a long history, with the first of their kind opening its doors in Scandinavia in the 1890s (Rentzhog 2007, pp. ix). Over the following years, the concept has been spreading its particular approach from its Scandinavian roots to being a global phenomenon. That being said, OAms are particularly well established in Western and Northern Europe, as well as in the US, but aspects of the OAms are recognisable in many other museum designations, such as archaeological parks and in extensions to conventional museums. On several points of interest OAms are demonstrating promising potential within the museology field. This includes various objectively successful elements of both educational and pedagogical, as well as, economic character integrated in their everyday management (Paardekooper 2015; Lyth 2006; Malcolm-Davies 2004).

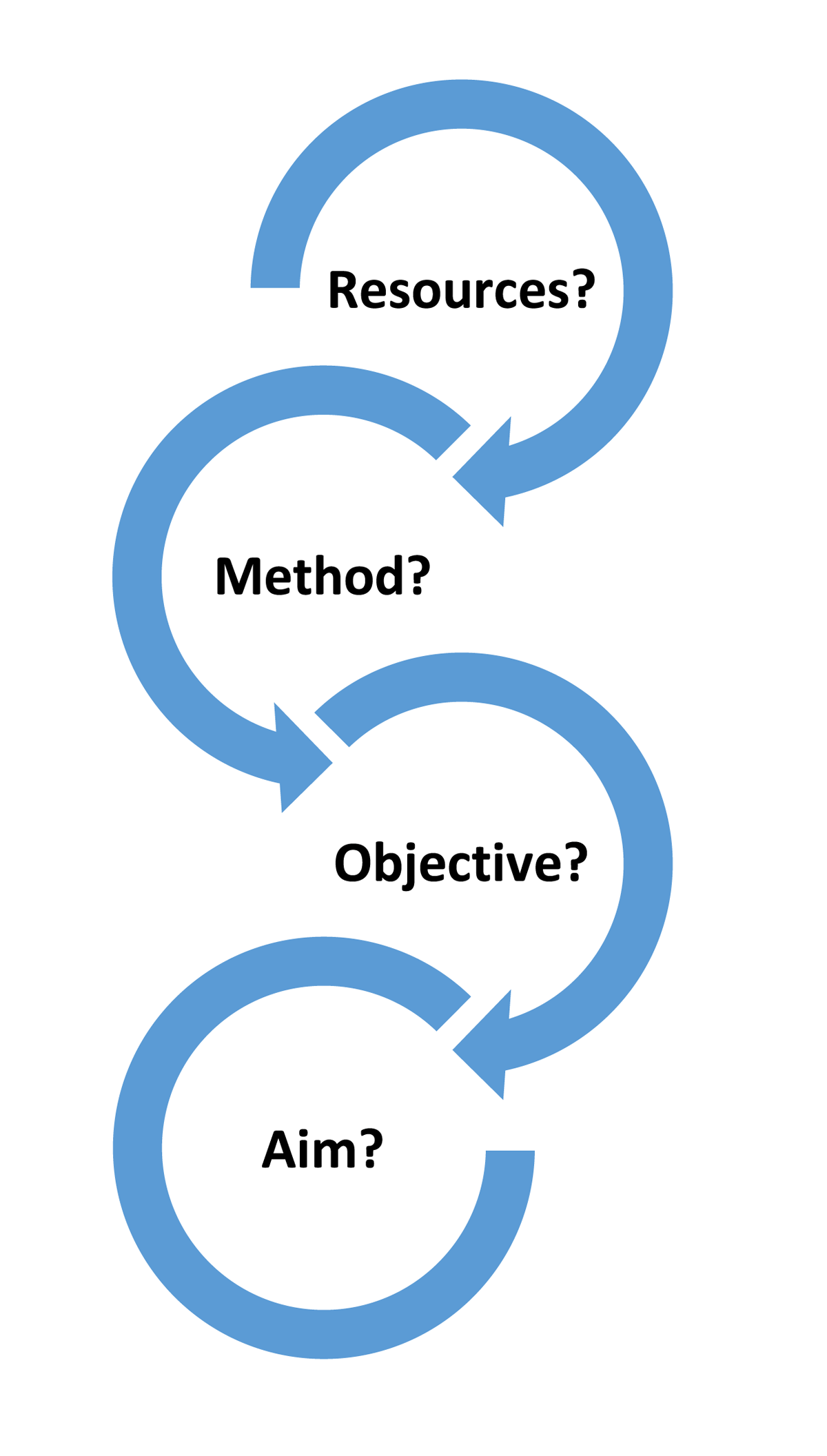

The first point of general interest concerns the socioeconomic benefits that OAms are able to generate through the diversity of visitors they can attract. Secondly, and very connected, are the learning impacts of their particular “active visitor” approach and thirdly, the inherent entrepreneurial approach to self-sustaining economic development. All of these elements are founded on the particular resources inherent in the OAm approach and how these are developed (Figure 1).

Figure 1

OAm conceptual approach.

OAms have from the start had a focus on the common people rather than the elite (Magelssen, 2004; Young, 2006; Williams-Davies, 2009). This is evident in their collections featuring the homes and businesses of the common people and can be argued to have heavily affected their visitor approach, as well as the socio-economic groups they are seen to represent and, as a direct consequence, attract (McPherson, 2006; Rentzhog 2007; Williams-Davies 2009). Whether or not this particular focus can be attributed, in recent years OAms globally have demonstrated a steady increase both in visitor numbers and the socio-economic diversity of their visitors (Rentzhog 2007, pp. 371; Paardekooper, 2012, pp. 197). This tendency is in fact very remarkable and should be viewed against the trend in conventional museums where, although visitor numbers are increasing, studies have demonstrated that the type of visitor continues to be limited to higher socio-economic layers, indicating a public understanding of the museum as an elite and, to some extend still, exclusionary institution (Ateca-Amestoy and Prieto-Rodriguez, 2013; Martin, 2002; Department for digital culture, 2018).

However, this promising development has been met by some critics with concerns regarding the perceived “disneyfication” of the cultural experience as it is communicated by the OAms (Lyth, 2006). This concern suggests that a pronounced focus on recreation as part of the museum experience will necessarily lead to a loss of integrety; a straying from the original purpose to becoming mere “arenas for pleasure rather than education” (Stephen, 2001; McPherson, 2006; Lyth, 2006). However, visitor studies at OAms demonstrate high levels of both visitor satisfaction and learning, indicating that a different approach to mediation is essential for a museum wishing to expand their visitor base while not being detrimental to the educational role of the museum (Moolman 1996; Nowacki 2010; Clarkson & Shipton 2015; Visitor studies, Lejre-Land of Legends 2015). Rather it has been suggested that a broader visitor base will require a different approach to learning and the ability to meet this need demonstrates an improved educational skillset (McPherson, 2006).

Of further interest to the museology community is the fact that OAMs demonstrate a very high level of economic self-sufficiency when compared to conventional exhibition focused museums. Nearly half of all OAMs in Europe generate more than 50% of their income and an entire 22% generate over 81% (Paardekooper 2015). This is compared to an average income generation of 20% in conventional museums (Paardekooper, 2015). Hidden in these numbers is the fact that conventional museums are much more likely to receive public funding than OAms and that this forced self-reliance has led to innovative entrepreneurial approaches to economic development (Hatton 2012; Paardekooper 2015). However, public funding in the heritage environment has been continuously diminishing since the 1990’s forcing a dilemma on all museums of how to properly achieve balance between educational goals and the increasing need for sustainable profit growth (Theobald, 2000, pp. 5).

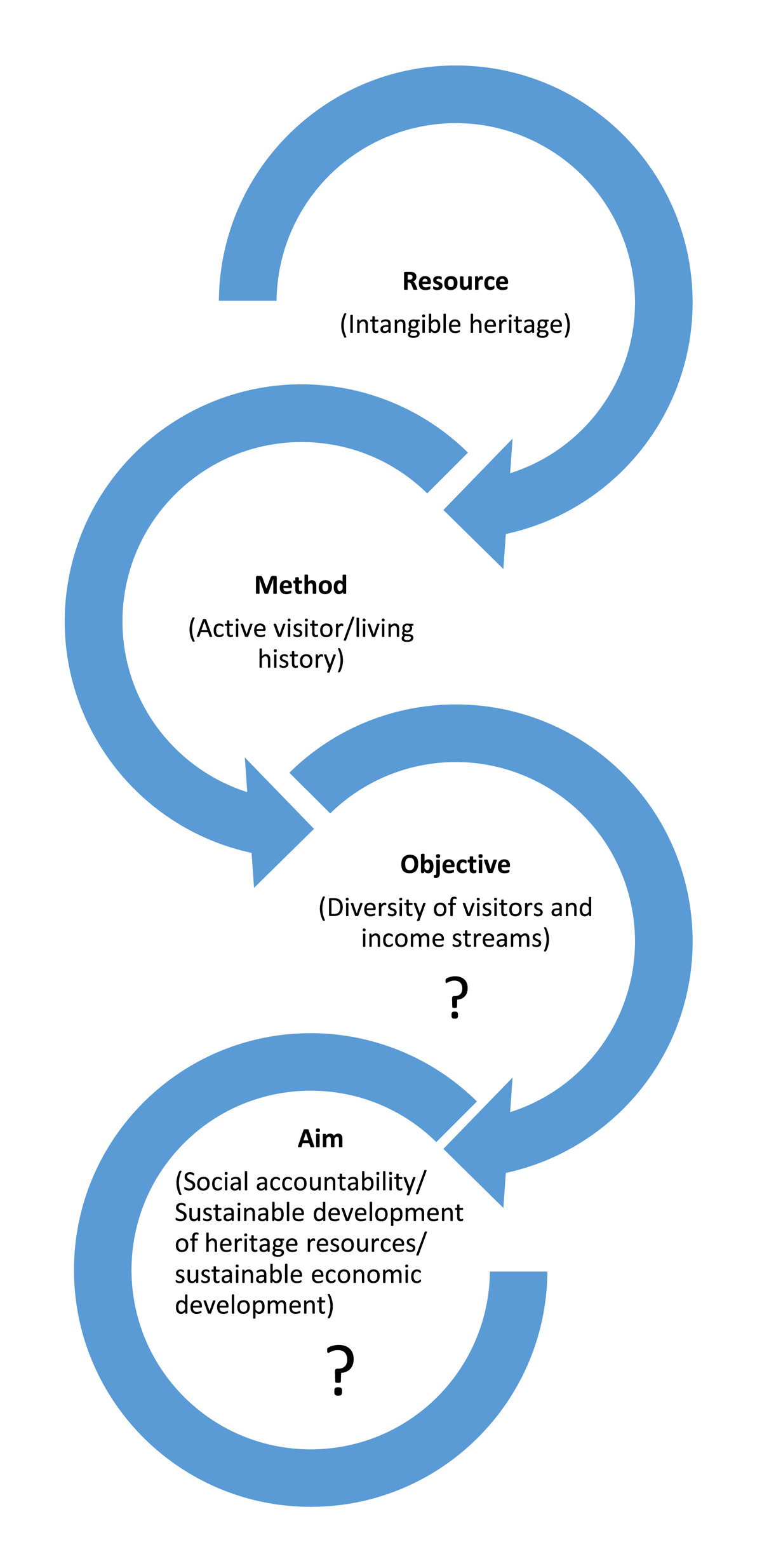

Despite these successes, and almost 130 years of global experience, very little research has gone into categorising the particulars of the OAm museology approach (Figure 2). A definition that can embrace all OAms, and defines the principal basis, as well as the particular elements of the OAms strategy, is still missing (Paardekooper, 2012; Oliver, 2013). As recent research has shown that the strategy comprises successful elements of both educational and economic potential, this lack of cohesive research and shared learning equates to an important lost opportunity for the entire OAm community (Paardekooper 2015; Lyth 2006; Malcolm-Davies 2004).

Figure 2

Hypothetical OAm museology model.

This lack of shared insights has various reasons, but primary amongst them is the fact that the established museology community has shown little interest in OAm approaches leaving it absent from serious research. As a result, studies into the OAM museology are almost entirely absent and have left the OAms community without an acknowledged position and starting point as a conceptual branch of museology (Paardekooper 2012; Lyth, 2006; Rentzhog 2007, pp. 371). Consequently, even OAms rarely publish on their organisational management policies and how these shape their particular mediation and resource development approach.

This paper aims to assess the mechanisms of the OAm approach with regards to development and particular aspects of their resources, and recommends an initial museology definition for the Open-Air museum concept. OAms are gathered under one as their common approaches of active visitor approaches and “living history” experiences are assembled and investigated. This aim will be achieved by identifying the underlying principle of the OAm approach that guides the choice and development of resources and extrapolate the “best practices” to form part of a unifying OAM museology. Lastly, this paper will explore whether the focus on active visitor participation and living history can be argued to constitute a sustainable approach to developing a profitable and sustainable “cultural product” using the intangible heritage.

1.1. Methodology

To achieve the aims stated previously, this study has performed an exhaustive literature review on OAms using the search terms; agricultural museum, folk museum, living history, experimental archaeology, heritage village, museum village, living farm, eco museum, and archaeological park, in order to include all types of OAms based on their commonalities in approach and regardless of their diverse designation. Most data have come from European or North American studies, as the largest percentage of OAms in any guise are to be found here. However, the inclusive search terms aim to include as many variations on the concepts as possible from a wide range of countries. OAms are not sought to be differentiated against one another but rather unifying elements are found and best practices are extrapolated in order to suggest a definition, which could bring them together in order to better share and benefit from experiences. As the literature on OAms is very limited, the findings have been complemented with data from several different methodological sources including the authors’ own international survey on OAms (Olinsson, 2019), in-house visitor studies and in-depth interviews with staff and management at selected OAm case studies in Denmark and England.1

England and Denmark were chosen as case studies as they both demonstrate a long history of successful implementation of the OAm concept, while also representing very diverse national approaches to funding. 15 OAms participated in the survey (2018), which was distributed to all 42 OAms in Denmark and England equalling a response rate of 36%. Respondents were equally sourced from the two countries. The online survey contained 18 questions and explored how OAms view themselves compared to conventional museums, what they consider to be their most important features, and what they see as their strongest potential. The survey put special focus on the how the museums perceived the use of active visitor participation, as well as the use and role of heritage crafts as an expression of their particular visitor approach. Representing, respectively, Denmark and England, Lejre, Land of Legends in Denmark and Weald and Downland, living museum in England were chosen for in-depth studies that included several rounds of interviews.

This wide array of data collection methodologies serves to examine and corroborate findings from the literature from global perspective in order to provide a comprehensive framing of the issue. However, even if the concept is global, by far most OAms are found in Europe and the US where the concept has been enthusiastically adopted. Even “newer” variations on the concept such as the “eco museum”, which has an ever growing following in Asia and the Americas, has 350, out of an estimated total 400, museums in Europe (Borrelli and Davis, 2012). For that reason, the study will inevitably be strongly influenced by “Western” data.

1.2. The problem of definition

Despite being established in the late 19th century, the term OAm has only been in use since the 1950s and there is, as of yet, no clear and accepted definition of what an OAm is (Oliver, 2013). The very vagueness of the term means that it can embrace a wide variety of sites, or contrarily, be omitted as a denominator in other places. This means that what could be termed under one as OAms, are instead known under many guises referring to their specific focus; agricultural museum, folk museum, living history, heritage village, museum village, living farm, eco museum, archaeological park, etc., or even indistinguishable from archaeological sites, as is often seen in the Mediterranean (Ali & Zawawi 2007; Paardekooper 2015). As such, even amongst the OAms themselves there is no commonly accepted understanding of what they are and what characteristics they share. Consequently, the differences between a ‘conventional’ exhibition focused museum and an OAm are perhaps more easily recognisable and can constitute a “general consensus” starting point on which to build an OAm definition (Paardekooper, 2012; Oliver, 2013).

Very simply put, a conventional museum tends to be artefact based, while OAms are activity based (McPherson, 2006; Paardekooper, 2015; Brown and Mairesse, 2018). Paardekooper (2015) who is one of the foremost experts in the field of OAm studies and cofounder of EXARC,2 classifies the OAms collection as: intangible cultural heritage resources – the “stories” that provide context- life, understanding and insights into the historical environment.

In 2008, in an attempt to address the issue of definition, EXARC presented a basic definition of archaeological Open-Air museums, which in many ways mirrors the ICOM 2007 museum definition. Their definition reads as follows:

“An archaeological open-air museum is a non-profit permanent institution with outdoor true to scale architectural reconstructions primarily based on archaeological sources. It holds collections of intangible heritage resources and provides an interpretation of how people lived and acted in the past. This is accomplished according to sound scientific methods for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment of its visitors.” (EXARC, 2008)

This definition covers the physical aspects of the OAm as well as the academic expertise that is characteristic of the concept and specifies the focus on scientifically based learning practices. Paardekooper is very much aware of the differences in the understanding of the intangible “collection” as the “stories” of past lives that OAms, better than any other kind of museum, bring to life through all their “living history” elements and participative visitor approaches. However, apart from mentioning the specificity of the OAm collections as “intangible heritage resources”, this definition (which is the most widely accepted definition), does not include organisational strategy or management, neither in terms of economy nor as an expression of their learning and mediation strategy. In this definition as in the literature in general, the particular museum strategy of OAms – their museology – is not considered.

2. The history of the Open-Air museum

When the first Open-Air museums were established it seems evident that the motivation was a desire to preserve the threatened cultural identity and traditions of rural communities in a time characterised by great social upheaval and change (Jong and Skougaard, 1992; Moolman, 1996; Williams-Davies, 2009). Similarly, the 1960’s was a period marked by social upheaval and stark social changes, resulting in a spike in interest in the lives of the “non-elite” and a re-evaluation of societal goals- including the interpretation of, and the collections of museums (Young, 2006; Davis, 2008, pp. 398). Perhaps in response to this upheaval, the traditional understanding of museums as a collector and preserver of the material heritage of humanity is questioned by ICOM (1971) as “not a manifestation of all that is significant in man’s development” and “lacking expertise and knowledge from other sectors of society”. Consequently, from this period onwards, the number of OAms worldwide grew exponentially, with new museums preserving the humble houses and businesses of the rural areas as well as industrial production sites, with many OAms originating as local community efforts (Young, 2006; Rentzhog, 2007; Davis, 2008, pp. 398).

This interest in the humble rather than the elite is a distinguishing feature of the OAm and, even to this day, most OAms acknowledge to have a significantly different approach to conventional museums. This is distinctive both in their choice of material and in their approach to learning, with active participation and living history being fundamental pedagogical and economic elements in the OAm museology. In this, the OAms differ from the conventional museum that uses innovative and participatory approaches for special exhibitions but whose fundamental approach is object based (Colomer, 2002; McPherson, 2006; Hayes and Slater, 2002; Zipsane, 2006).

2.1. Open-Air museums in the literature

Despite almost 150 years of experience gained on a global scale, there are to date almost no larger studies on OAms and the development of the OAm as a conceptual approach to museum management is hardly touched upon (Paardekooper, 2012, pp. 31; Rentzhog, 2007, pp. 1; Davidson 2015; Reussner 2003; Ross 2004; Lyth 2006; Jong & Skougaard 1992; Mills 2003). The few studies into OAms that can be found, too often focus on a reiteration of the history of the early OAms, followed by a descriptive or comparative piece of one or more OAms, very often based on personal observations after a visit to the museums (i.e. Angotti, 1982; Magelssen, 2004; Shafernich, 1993, 1994; Nowacki, 2010). Moreover, since the OAms themselves very rarely publish on their particular management approach and their organisational strategy (Paardekooper 2012, pp. 234), the result is that studies operate in a field lacking in academic reference and framing and, consequently, these studies often demonstrate limited academic value and scale. The OAms themselves blame this lack of research on limited economic scope rather than a lack of interest. However, it does also reflect a priority, and is seemingly the result and perpetuator of a catch 22 situation that does not help the OAms gain an established position in the museology field. This failure of the OAm community to penetrate the academic environment, is expressed in the general museology literature by the fact that OAms are conspicuously absent in the general literature on museum management and museology or worse; only mentioned in a derogatory aside (Lyth 2006).

2.1.1 Critical and missing inclusion in the museology community

So how are the OAms perceived in the established literature? Frequently, studies only superficially include the OAm experience and are often formulated within a debate that is set within the confines of conventional museum practices. This framing consequently forms the basis on which the academic reputation and professional evaluation of OAms are based. This results in negatively biased assessments of their contributions as cultural institutions (Ali & Zawawi 2007; Lyth, 2006; Malcolm-Davies, 2004; Williams-Davies, 2009).

The popular appeal of the OAm has been dubbed “edutainment” contracting education and entertainment with a negative focus on the entertainment part and a lacking assessment of the education part and is denoted as populist (Lyth 2006; McPherson, 2006; Rentzhog 2007). A concept with negative connotations in traditional museology literature where we repeatedly come across the “popular” as counter-posed to “responsible” museum practices (Stephen, 2001; McPherson, 2006).

This very criticism seems to highlight that, while the need for a “democratisation” of museum practice is seemingly accepted in the literature, it could be argued that this is in reality illustrative of a politically forced aim, rather than a voluntary recognition, of the need for change (Kotler and Kotler, 2000; McPherson, 2006; Hayes and Slater, 2002; Coffee, 2008; Ateca-Amestoy & Prieto-Rodriguez 2013). In this environment, it could perhaps credibly be argued that OAms have a representational problem extending all the way to important policy making organisations such as ICOM and UNESCO, and that this reflects a belief system in museology circuits that a democratisation of culture comes at the expense of a traditional “elite” experience of which the OAms are not part (Stephen, 2001; McPherson, 2006). The perception that, as cultural tourism grew and became available to the general population it changed status, going from an “elite” activity to “lowbrow” mass tourism, can unfortunately still be found in parts of the museum community, demonstrating the continued “push and pull” between the traditional purpose and values of museums and the “trends” relating to their social role (Kotler and Kotler, 2000; McPherson, 2006; Coffee, 2008; Brown and Mairesse, 2018).

Overall however, the debate in the museology environment is seemingly moving towards a more liberal position and voices in ‘new museology’ circuits refer critically to the “old guard” of heritage professionals as “traditionalists” or “elitists” whose conservative views are opposed to their aim of greater social inclusion and improved learning opportunities (McManamon, 2000; Davidson, 2015).

3. Museology and heritage management definitions

A heritage management definition will support the basis of an OAm museology definition.

Looking at the literature on heritage management, often referred to in the literature as Cultural Resource Management (CRM), it becomes immediately apparent that the focal point of heritage management is the resources. From a heritage management perspective Knudson (2001, p. 361) states that; “management of something is controlling it insofar as is humanly possible”. “Management is the attainment of organizational goals…through planning, organizing, leading and controlling organizational resources” (Knudson, 2001, p. 361). She continues; “good stewardship requires affirmative resource management, including the management of our intangible and tangible cultural resources” (Knudson, 2001, p. 359). These statements bring to the fore the intrinsic connection between resources, the varying nature of these resources and management.

Management as such is viewed as the process whereby human and non-human resources are directed towards the achievement of said organisational goal. In the context of heritage management, organisational goals will include a set of “values” relating to the protection of the heritage material as well as aspects of social accountability, which will constitute an inseparable and fundamental part of the heritage management process and strategy. This expands the understanding of organisational goals in a heritage context to include a value informed policy.

With this in mind, this paper will define heritage management as:

The attainment of organisational value informed policy goals, understood as conscientious heritage preservation with social inclusivity and accountability. Achieved in an effective and efficient manner through planning, organizing, leading and controlling, intangible and tangible, cultural resources.

4. Strategy and policy at OAms

Paardekooper (2015) classifies the OAm “collection” as intangible; the “stories” that provide context to the explored lives and understanding and insights into the historical environment. The specific elements that make up the OAm resource management approach are based on this principle and form the basis for both their educational and economic ventures. The recognition of the defining difference in collections at conventional (object focused) museums and OAms (intangible heritage focused) is providing an understanding of the diverse approach to visitor interaction in OAms. At OAms, as their resources are perceived very differently, they are also managed very differently.

Apart from the pedagogical feature of this interpretation of their collection, the intangible heritage is also fundamentally connected to the various income generating activities at the OAms (Interviews, Holten, Lejre, Land of Legends 2017; Rowland, Weald and Downland 2016; Pailthorpe and Purslow, 2017; Survey 2018). The potential of the intangible heritage as a resource is recognised in the conventional museology literature and has been discussed in various settings within the heritage field (Palmqvist 1997; Carter & Geczy 2006, pp. 162; Hooper-Greenhill 2007, pp. 1, 177). In new museology literature it is argued that we need ‘diverse as well as wide ranging educational and outreach activities’ (Hooper-Greenhill, 2004; Hooper-Greenhill, 2007) and, extending into the economic sphere, current research supports both the need for, and the success of, museums with entrepreneurial activities and a clear strategic focus. (McPherson, 2006; Hatton, 2012; Pop et al., 2018). ICOMS’ recent academic debate relating to a revision of the 2007 museum definition, has seen much attention on the economic value that museums represent in society, as well as a move towards a more critical vision of their educational role and the societal challenges facing the modern museum. Both of which emphasises the importance of who pays for the management of heritage resources, and how (Brown and Mairesse, 2018). This debate resulted in a 2019 vote for a new museum definition but no new definition has, as of today, been accepted. However, while addressing societal and educational concerns for the modern museum, this definition did not include considerations for a sustainable economic management model for museums (ICOM, 2019). Notwithstanding, these concerns continue to permeate the academic debate, including in a recent study that attempted to connect the potential of intangible educational and economic approaches in the heritage industry and suggested that these resources encompass the potential to develop a “sustainable cultural product” (SCP). This is defined as “a marketable product, based on intangible heritage, which does not cause damage to the heritage fabric even though it is based on, and markets, heritage” (Olinsson and Fouseki, 2019, p.487). However, without the strategic focus, (a well-developed museology or heritage management approach) any entrepreneurial activities run the risk of entering the sphere of ultimately damaging economic activities. OAms are advancing fast in employing entrepreneurial activities, making the need for developing well-defined organisational policy goals, for the aim of sustainable development, very immediate.

In the following sections, this inherent feature of the OAms will be explored to recognise its specific uses concerning resource management, and as a defining element inherent of a museology approach.

4.1 Intangible heritage in the Open-Air museum approach

The various uses of intangible heritage in a museum setting have one particularly appealing feature setting them apart from “use” of the more fragile material heritage; it is sustainable. Furthermore, far from being detrimental to the heritage material, the continued use of the intangible heritage, i.e., in heritage craft and other types of “living history”, is important to sustain and preserve valuable knowledge (Bineva, 2010; Olinsson and Fouseki, 2019).

The aim and potential benefit of OAms resource management approach can be divided in three streams; (i) improved social inclusion leading to a growing number of visitors (ii) improved experience and learning outcomes among visitors and (iii) improved economy through a diversification of their income streams. All approaches are based of their principal understanding of their collections as intangible and all approaches are strongly interconnected.

The diversity of cultural activities at OAms has been shown to attract a wide variety of audiences as well as broadening their income streams. In the following we will explore the elements making up the two remaining streams in OAm management approaches, which are fundamental for achieving this; the active visitor as an educational approach and the use of the intangible heritage as an entrepreneurial economic feature.

4.2. Active visitor participation and living history- learning at OAms

The literature suggests that the strongest and most particular features in the success of the OAm management approach are the active visitor participation and living history approaches to learning/education- often termed “edutainment” (Bloch Ravn, 2010; Rentzhog, 2007, pp 415). The 2018 survey among OAms in Denmark and England strongly supports this finding, as the participating OAms overwhelmingly point to active participation and living history as the two strongest features of their particular management approach (Survey 2018). Amongst responding OAms, 80% agreed or strongly agreed and only 6.67% disagreed to some extent (2 on a scale from 1–5). Comments from the participating museums clearly demonstrate how the tactile approach of the museum is perceived as immensely important to the learning experience; “visitors need to be active participants to gain most value from open-air museums”, “demonstrations make the site come alive”, “visitors should look, see and feel”, “make, touch and discover” and even mottos; “let me try and I will understand”.

Another noticeable difference between the OAm and conventional museum visitor strategies lies in at whom their educational programmes are primarily aimed. Hooper-Greenhills’ (2007) studies regarding learning outcomes, pedagogy and education, describe a misused potential for adult learning programmes in most conventional museums as the focus is overwhelmingly on children’s programmes. This means that conventional museums have opened up a plethora of learning experiences for their adolescent audiences with priority given to formal learning and school services, while the learning experience engaging the adult visitor is pedagogically much more restricted (Arts Council England, 2016; Hooper-Greenhill, 2007). Many conventional museums do include highly modern, diverse and innovative educational approaches at special exhibitions. However, while demonstrating their ability and range of pedagogical tools, this is not their main approach and it creates a dichotomy between the “spectacle” of the special exhibition and how the adult visitor is engaged at other times (Hayes and Slater, 2002).

Rentzhog (2007, pp. 357) in his major study on OAms from 2007 concludes that; “hands-on and visitor participation are the most noticeable present developments at OAms”, and that; “the museums that have gone furthest in this direction also seem to be the most successful”. In heritage settings, situated in between the conventional museums and OAms, for example science museums, historical houses and natural history museums, the same trend is also evidenced. Rentzhog laments how “edutainment”- the educating through entertainment is portrayed in the literature as a lowbrow “method of achieving more visitors”, rather than an important educational method. Too often, he continues; the educational aspects of OAms have been dismissed as irrelevant in a concept likened to “fun-parks” (Rentzhog 2007, pp. 415). In view of this criticism, it is very interesting to note that a report from 2003 on the learning impacts of museums commented that: “Despite their importance as places of learning, little information is known about how [conventional] museums impact upon the learning experiences of their users” and that “not all museums see themselves as places that should primarily focus on the learning experiences of their users” (Research Centre for Museums and Galleries, 2003, p. 4). Interestingly, the 2018 Denmark/England OAm survey, demonstrates a strongly perceived link between the OAms as institutions of learning with 73.33% percent of respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing that “teaching/learning” is important in OAms (Survey 2018). Only a small minority- 6.67% sees this feature as less important. Furthermore, there is nothing to seriously suggest that the museum as a context for recreation is unable to maintain its core function of educating. Rather, science and experiments are fundamental to the way OAms relate to both the professional archaeologist and the public (Stephen, 2001, McPherson, 2006) and research indicates strong potential for learning outcomes through hands-on learning (Bineva 2010; Clarkson & Shipton 2015; Clarkson & Shipton 2015).

Several visitor studies have indicated that visitors want to be entertained as well as “educated” (Bagnall, 1996; Malcolm-Davies, 2004; Nowacki, 2010). Visitors in Bagnalls’ 1996 study consistently mention the meeting of enjoyment and learning as the main satisfaction parameter of their visit. Having passed the test of time, an OAm visitor study by Nowacki in 2010, overwhelmingly confirms that this is still the case. In both studies the visitors describe feeling and experiencing that the OAm provides a physical experience that stimulates their imagination (Bagnall, 1996; Nowacki 2010).

Rentzhog (2007, pp. 415) speculates that the evocative nature of the OAm experience will help the visitor to remember; it becomes an experience that the participants “take in” and, which will stay in the memory. In academic history, the same concept is utilised in “evocative writing” and in previous museology studies for conventional museum displays, the term “numinous” has been used to describe intense engagement and emotional connection with the spirit of the time of the objects (Latham 2013; Rentzhog 2007, pp. 415).

However, and contrary to what some critics believe, it is not only the sensory experience that attracts visitors. In both Bagnalls’ (1996) and Nowackis’ (2010) studies, the visitors emphasise the importance of the fact based experience, they want to learn as well as “enjoy”, and studies clearly demonstrate that OAm visitors have gained new knowledge after their visit (Malcolm-Davies, 2004; Nowacki, 2010).

Interestingly, visitor studies at Bokrijk OAm in Belgium contradict Nowackis (2010) and Bagnalls’ (1996) findings, as in-house visitor studies showed that only a minority of visitors came “to actively seek knowledge” (Rentzhog, 2007, pp. 343). Nowacki makes an interesting observation, which might explain this inconsistency and link Rentzhogs’ theory and Bokrijks experience. Nowacki (2010) states that going to an OAm (or any other museum) is considered a leisure experience, as it is a choice of how to spend a sizeable portion of one’s free time. Nowackis’ study found that the visitor; “in their leisure time are not willing to use written materials which require much more effort and competence than a casual conversation [with staff] or asking questions” (2010, p. 190). As most OAms will have staff on the grounds, costumed or otherwise, doing demonstrations or simply engaging with the visitor and, in general, being available for questions, the OAms are engaging with the visitor and offering learning opportunities in their preferred manner.

Amongst all OAms there is an understood aim to use story telling (living history) and introduce new forms of interpretation with emphasis on engaging and easily accessible information, in order to ensure an educational and enjoyable visit (Rentzhog, 2007, pp. 343). By offering the opportunity to have casual conversations with staff, OAms deviate significantly from the conventional museum practice where, unless they have pre-arranged to partake in a guided tour, visitors will rarely encounter museum staff in the exhibition area. This approach does not make the OAms less educative- “indeed it could be argued that they may be more so, as it is what allows them to attract a more diverse audience than conventional museums”, however, “from a “traditional” or “elite” point of view, the learning potential is less obvious” (McPherson, 2006, p. 53).

Overall, looking at visitor approaches at OAms it could reasonably be argued, that the vast majority of OAms are aiming their visitor approach towards the exact kind of learning environment, which the visitors have shown to prefer as well as benefit from. In practice this means easily accessible knowledge, little written text, staff available for questions or demonstrations and active engagement of the visitor. This is an approach that has shown to be equally engaging for the adult, as well as the child, visitor and, as a leisure and learning experience, this is highly popular among families. This does not mean that conventional museums are not increasingly employing these types of approaches in accordance with new museology principles, but rather that they are foundational to the OAm approach and have been since their very beginning.

4.3. The economic benefits of entrepreneurial diversification

At OAms, the learning conveyed through the diverse approaches of active participation and living history, is aimed at both adults and children. The use of heritage crafts, which many OAms offer as part of their daily museology/management approach in order to actively engage their audience, have been shown to engage the adult, as well as child audience equally- even when activities were primarily aimed at children (OPENARCH, 2015; Interview Holten, Lejre, Land of Legends, 2017; Lyth, 2006). However, the use of crafts courses, separate from the day-to-day museum visitor management, is almost fully aimed at an adult audience and OAms demonstrate high levels of entrepreneurial activity in their pervasive use of heritage crafts as part of their visitor engagement strategy (interviews Rowland, Weald and Downland, 2016; Holten, Lejre, Land of Legends 2017). These courses add an extra element to the heritage experience that the museum offers, by giving the participant a much deeper understanding of the practice, and bridging “dead” heritage into the realm of “everyday useful” practices and skills. It is a museum practice that benefits the visitor, the heritage crafts practitioner, sustains the viability of the heritage craft itself and economically benefits the museum. Due to these inherently desirable and sustainable benefits, this approach could be considered as developing a “sustainable cultural product” (SCP). As previously mentioned this is defined as “a marketable product, based on intangible heritage, which does not cause damage to the heritage fabric even though it is based on, and markets, heritage” (Olinsson and Fouseki, 2019, p. 487). Such an approach carries enormous potential for the heritage sector and even if the conceptual idea, that this process is leading to the development of a SCP, is not fully recognised, the methodology is appreciated among the OAms who consider the use of crafts as part of their museum approach to be a highly successful approach. 66.67% agree or strongly agree with that statement, while only 13.33% disagree (survey 2018). Even amongst the OAms disagreeing, comments make it clear that the issue is regarding their actual capability to invest, in order to develop workshops, and with the concern that benefits are not properly shared between museum and crafts professionals (survey 2018). Furthermore, when considering the potential of crafts in OAms, all the participating museums agreed that they would benefit from further integrating crafts into their management model. Comments indicate several avenues of perceived potential- from the integration of crafts as a pedagogical tool, an opportunity to develop strong visitor experiences, as well as for the economic potential benefit (survey 2018). In Lejre, Land of Legends in Denmark, crafts courses were only introduced in recent years and the interest these have generated indicates an untapped and great potential (interview Holten, Lejre, Land of Legends, 2017). At Weald and Downland in England, a world frontrunner in this development, heritage crafts courses running parallel to everyday museum management, creates a substantial part of their income at around 20% (Interviews, Rowland, Weald and Downland, 2016; Pailthorpe and Purslow, 2017). Furthermore, both the current and previous management agree that Weald and Downland has not yet reached its full potential from this approach. Lejre-Land of Legends in Denmark, demonstrates another example of entrepreneurial potential with an innovative event programme for businesses, turning many years of pedagogical experience into successful business leadership and team-building events built around the heritage experience (interview Holten, Lejre, Land of Legends 2017). This approach has been criticised in museum circles but it is an approach that the Lejre museum perceives as building on their core strengths and experiences in an innovative and economically beneficial way for the museum.

Apart from drawing on the pedagogical experience of the museum, this type of events draws on a range of elements defining the OAm; the open-air experience, the space and the evocative environment (Interview, Holten, Lejre, Land of Legends, 2017). However, even if OAms see benefits from their size and park-like environs, this also means that they are usually located in rural and isolated locations. Remarkably, at both Weald and Downland and Lejre, Land of Legends, their courses and events attract participants who are not sourced from the regular visitors at the museum, further widening their visitor base and potential for future entrepreneurial activities and indicating that the diversification within the OAm approach has expanded the group of both visitors and other adult “users” in ways not previously recognised (interviews, Rowland, Weald and Downland 2016; Holten, Lejre, Land of legends 2017).

In the years after the 2008 financial crisis, heritage sites and institutions saw huge cuts to their budgets and, along with general economic insecurity, economic spending, including on such activities as museum visits, naturally saw a decline. In this environment it is very interesting to note that while Weald and Downland, could attest to the fact that course participation for more “frivolous” pursuits based on personal interests saw some decline, the museum saw an upward trend towards courses that could add skills in current professions (interview, Rowland, Weald and Downland, 2016). Overall, the number of course hours rose steadily throughout these years, demonstrating the value these skills still hold in society, as well as the potential this avenue holds for OAms.

5. Discussion and Open-Air museology definition

As demonstrated, OAms operate over a vast array of topics and under varying guises but share an overall understanding of pedagogical approaches and aim.

They furthermore, have a shared perception of their collections as being intangible, which has led to a diverse pedagogical approach and various derived benefits.

The integration of “living history” and an active visitor approach means that at OAms, professional staff of various capacities are on the grounds interacting with visitors. The opportunity to talk to staff, ask questions, or lean back and listen to stories, as well as the active participation in organised activities, all form part of a museum experience, which is unique for OAms and allows for a learning experience catering to a wide range of visitors with various levels of interest and previous knowledge.

The result is that OAms attract visitors from a broad section of society, including an audience that “conventional” museums have struggled to attract. The literature, including visitor studies, furthermore indicate that activities, be that historical daily chores or particular crafts demonstrated by staff that actively involve the visitors, are an outstanding pedagogical tool, which leave a lasting impression on the visitor, vastly increasing the enjoyment, as well as the learning experience of the visit.

This does seem to indicate that the particular OAm pedagogical approach can be directly translated into potentially attracting a more diverse audience, a varied and attractive, as well as lasting, learning experience for visitors of many backgrounds and, consequently, a growth in visitor numbers at any given museum.

Another remarkable observation of the study is that OAms, to a much higher degree than conventional museums, aim their mediation and pedagogical efforts at an adult audience. This has attracted a separate group of visitors to the museum and the use of the intangible knowledge in “extracurricular” activities such as heritage crafts courses, have further widened the group of potential audiences in the museum to include visitors who would not otherwise visit the museum. This has added a very significant economic benefit to their approach. This is a very important and, to a wide degree, underexplored potential for a heritage field that, as a whole, have been suffering massive cuts in public funding in recent decades. For that reason, the development of such diversified income generating activities, sustainably based on the intangible heritage, is highly significant as a promotor of sustainable economic self-sufficiency for the museum communities of the future.

The particular approach of the OAms has been shown to have many advantages ranging from their ability to attract a wide audience, over their pedagogical strengths and their ability to develop broadly ranging income streams to support an independent economic base. Above we have looked in detail at the particulars and derived effects of the specific elements making up the museology approach of OAms. It is evident that various successful experiences and methods are generally applied in OAms, and that innovation and attempts at applying new approaches based on the same foundational ideas are also under way. However, it is equally evident, that the conceptual museology approach of OAms has not been considered adequately in the existing literature. In part due to, ideologically perceived differences, and that, as of now, no fully encompassing museology definition for OAms exists. The lack of research into the OAm strategy from within the museology field impedes dissemination of knowledge and is an obstacle to furthering development, as museums do not benefit from experiences made around the world. It is also problematic for its refusal to at least neutrally review, the democratisation process of the museum experience, which the OAm approach can be seen to constitute.

In an effort to address this gap, and suggest an encompassing museology for OAms, this paper considered the resource development particular to the OAm approach as elements defined by their organisational policy and management. Some of these can be seen to be particular to OAms, while others are shared across the spectre of museums, while others again are increasingly incorporated into mainstream museum practices. The organisational policy is categorised as the value-based aim and is defined as the strategy underlying the resource development approach of the museum.

In a museum context, this strategy will, to a large extent, be decided by the collection. OAms are dedicating themselves and their mediation efforts to a different understanding of what a museum collection is. The OAms perceive their collections as intangible; inherent traditional knowledge and stories, rather than material heritage. At OAms this intangible collection is intrinsically connected to their learning and pedagogy approach, as well as their various income generating activities.

The OAm organisational policy goal can hence be defined as; The development of a museum experience and economic foundation, which is based on the mediation of an intangible collection through active visitor participation.

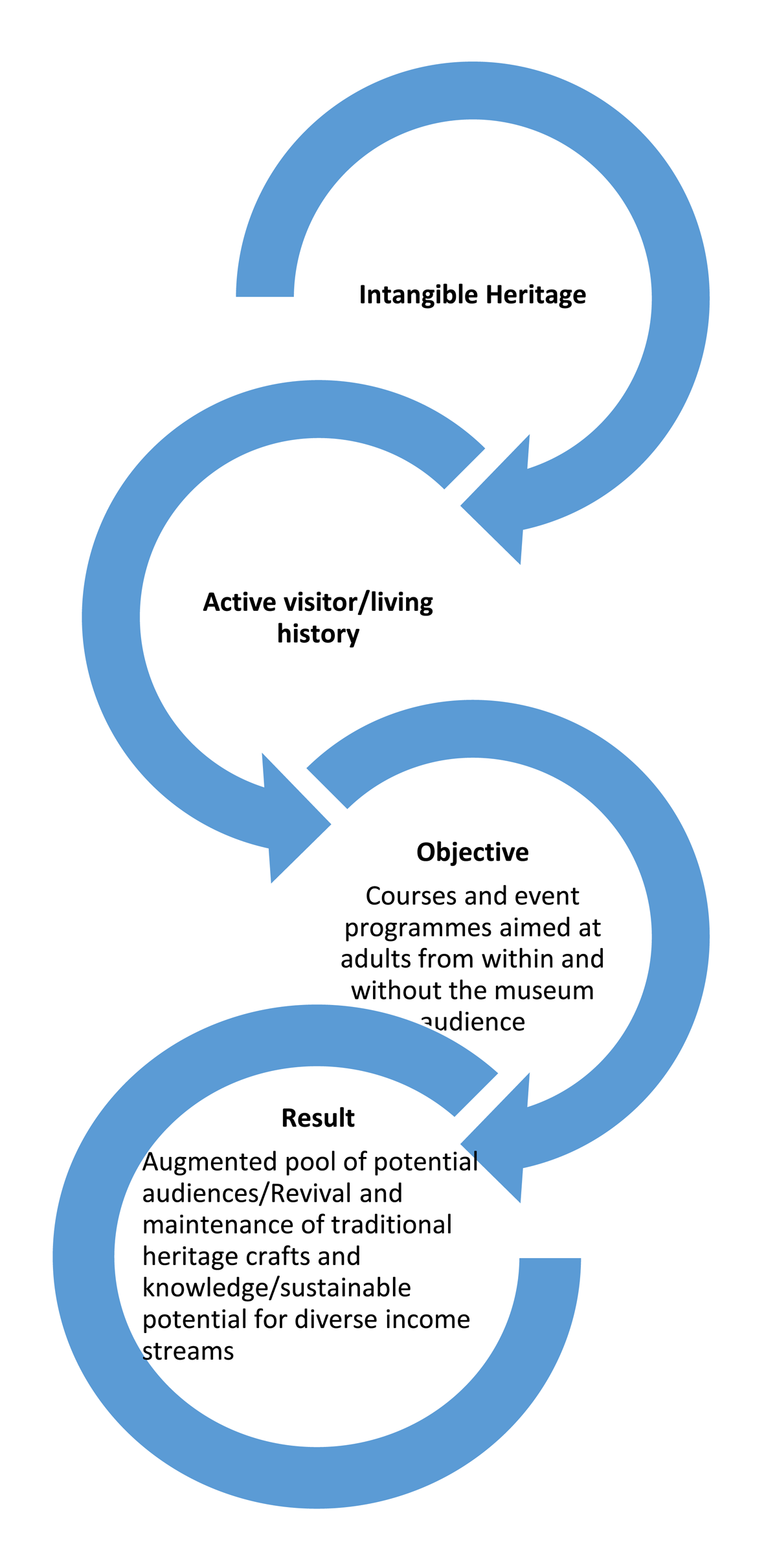

As established, the resource streams at OAms can be divided in three branches; (i) improved social inclusion leading to a growing number of visitors (ii) improved experience and learning outcomes among visitors and (iii) improved economy through a diversification of their income streams. Together these streams constitute, (a) social accountability; the willingness and ability to attract a socio-economic diverse group of visitors, (b) economic sustainability; entrepreneurial activities in several streams enabling the museum to develop high levels of economic independence, and (c) cultural sustainability; the use of intangible knowledge as part of maintaining and protecting the heritage material and empowering a living heritage. Figure 3, demonstrates how the aspirations inherent in the OAm approach are realised through well-defined approaches and specific objectives.

Figure 3

The established OAm model.

These three resource streams are all based on the intangible resources at the OAm and are highly interdependent. The heritage context means that sustainability of the resources is an overarching aim of the management approach. Utilisation, as well as development, of resources are established by the limits, which care and maintenance of the material stipulates. In OAms, all resource streams operate very consistently within confines of sustainability. In the case of the intangible heritage, use is what maintains the heritage and development efforts can even specifically be aimed at supporting heritage that is in danger of falling out of use.

As such, this paper suggests a museology definition for Open-air museums which reads:

An Open-Air museum is activity based and is centred around true to scale architectural reconstructions, as well as repurposed historical buildings. The aim is to provide an immersive experience into peoples’ lives in the past.

The museum learning experience and economic foundation is based on the mediation of an intangible collection through active visitor participation. This intangible collection will be utilised to develop three highly interconnected streams of resources, fulfilling specific aims of (a); social accountability- a diverse pedagogical methodology using active participation and living history to attract a socio-economic diverse group of visitors, (b); economic sustainability- entrepreneurial activities build on developing intangible heritage courses, and (c); cultural sustainability- using the intangible heritage as a means to maintaining and developing heritage crafts and living history.

6. Conclusion

OAms have chosen to rely heavily on their intangible heritage resources for their pedagogical approach and to build their “product” and brand, and are popularly known for their active visitor, as well as living history methodology. Their resource management approach is firmly built around the active visitor on site, as well as in courses running parallel to their core museum activities, and their living history activities. All elements are based on the development of intangible heritage features into physical and bankable “products” and are, furthermore, a successful pedagogical tool taking particular aim at the adult visitor and including the visitor who would normally avoid museums. The aim of this paper was to formulate an initial museology definition for OAms. To address the concept of museology in an OAm context, the museum was considered both for its organisational policy goals, as well as for its particular management approach. Unifying elements were considered and experiences from best approaches were utilised to exemplify the best approach an OAm can take. Whereas not all of the particular elements of the OAm museology can be applied at any museum at any given time, the approach offers a variety of expressions and valuable experiences, which most museums could benefit from. At its core the approach of OAms offers an understanding of the heritage, which goes deeper than the factual material knowledge. This ability to use the intangible knowledge to engage the visitor and tell stories surrounding the facts, is applicable in all museum settings and can help to communicate narratives so that they will be adopted more broadly. Undoubtedly, the static museums of the 19th century are a dying breed and many “conventional” museums do an amazing job with interactive and innovative exhibitions, which employ many of the strategies highlighted from the OAm approach. However, conventional museums are using these approaches in “special” settings rather than as a norm and, while they are making efforts to move away from their traditional beginnings, the OAms set out from an entirely different starting point. As such it would be surprising, if OAms did not have valuable experiences to share.

In conclusion, regardless of whether an OAm museology has been recognised at this point in time, OAms are operating with a highly specialised approach. The OAm approach shares the basic organisational value-based aim of all museums relating to the duty towards protection of the heritage and to mediate their collections as broadly as possible.

However, from this common foundation the OAms have developed a unique and innovative understanding of their own collections and how they choose to engage with the public and utilise their resources. The perception that a collection, which consists mainly of intangible heritage, is a viable source for sustainable development if utilised through innovative and entrepreneurial approaches, is giving OAms a real advantage when compared to the conventional museum approach and has given roots to the development of a “Sustainable Cultural Product”. However, for OAMs as well as conventional museums to be able to wholly benefit from this potential, it is necessary to fully understand and establish the principles supporting their approach and disseminate this knowledge where it will add potential and benefit. This would require for the OAm approach to be adopted into the mainstream museology literature where it would benefit from expert knowledge and scrutiny as well as from greater dissemination.

Notes

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to staff and management at Land of Legends in Denmark and Weald and Downland Living museum in England for giving their valuable time to answer questions and educate me on the life behind the scenes in an Open-Air museum. I would also like to express my gratitude to Professor Kalliopi Fouseki from the Institute for Sustainable Heritage at University College London, for sharing knowledge and experience, and adding valuable insights to this study. Finally, I would like to express my gratitude to the Augustinus Foundation of Denmark for economic support, which has helped make this study possible.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.