Introduction

Scholars have long argued that museums are not neutral landscapes but rather “political spaces where society frames its authorized culture, history, and identity” (Onciul, 2013, p.81). Museums possess a certain amount of cultural authority (Boast, 2011; Harrison, 2005; Karp, 1991) that influences the perceptions of museum visitors (MacDonald & Alsford, 1995; Onciul, 2013). For example, in instances wherein the exhibition is about Indigenous cultures, museums have the power to shape the image visitors have of the featured Indigenous cultures and often these portrayals have been replete with stereotypes (Silvén, 2014). Research indicates that in the 1800’s, museum exhibitions positioned Indigenous Peoples amidst the “flora and fauna”, which implied that they were regarded by dominant culture as part of the “natural history” rather than ‘social’ history (Hooper-Greenhill, 2007, p.195; Kalsås, 2015). Silvén (2014) argues that if “museums have the power to produce problematic conceptualizations about people, they should be able to contribute to the opposite as well, and help create alternative images and narratives” (p.68, emphasis added). In this vein and over the last two decades, the notion of participation, coupled with issues of justice have drawn pronounced attention from museum professionals and academics alike (Kinsley, 2016; Sandell, 1998).

In Changes in Museum Practice (Skartveit & Goodnow, 2010), an edited book published in association with the Museum of London and sanctioned by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Goodnow (2010) identifies four forms of participation in museums, namely access, reflection, provision, and structural involvement. The first aspect, participation at the level of access, can be related to the physical design of the museum, particularly architectural barriers and accessibility features, such as ramps, lifts, Braille, and several other elements that make the museum more accessible for everyone. Access can also be linked to the debate of entrance fees and the potential exclusion of visitors with fewer financial resources. In a similar vein, language barriers might prevent participants from fully engaging in the museum’s exhibit, leading them to feel unwelcome and/or excluded (Dawson, 2014).

Participation by reflection “stems from a shift in museums’ perceptions of their changing role in society and their need to retain audiences” (Goodnow, 2010, p.xxvi). From this vantage point, participation at the level of reflection requires museums to address the diversity of their audiences. The third form, participation at the level of provision, entails contributions from the living communities portrayed in the museum context. In this case, non-professional individuals, representatives of the community, and other people from different backgrounds are encouraged to be involved in the exhibition design or museum programs by donating objects and providing personal stories. Participation at the level of provision adds value to the museums’ experiences through its allowance of pluriversal narratives. It can remedy gaps in the “official” museum narrative, provide correction to the curators’ interpretation, and/or create space through which personal stories that add an emotional impact to the overall experience can be shared. This form of participation does involve some risks in that the ‘unofficial’ personal stories and the ‘emotional baggage’ that originate from them can often be exploited as well as other kinds of consumption without appropriate recognition. The last form of participation is structural involvement and it entails two levels. One level involves appointing individuals from the community to museum advisory boards, whilst maintaining the final decisions on the exhibitions or the projects to curators and designers. The other level necessitates employing some community members as museum staff members who hold positions as directors, curators, and other key roles. According to Goodnow (2010), the aforementioned forms of participation are not presented in order of importance; rather, different situations require distinctive types of participation. By the same token, they are not mutually exclusive. Furthermore, a given museum can get involved in two or more forms of participation.

Scholars argue that participation of all the stakeholders is “a moral obligation for institutions with a genuine commitment to community service and [the pursuance of] social justice issues”, particularly museums operating within or in collaboration with Indigenous or other marginalized communities (Robinson, 2017, p.862). Notably, Goodnow’s (2010) seminal discussion on forms of museum participation cannot be adopted without grounded attention to the broader societal predicaments endured by Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color (BIPOC) that are often depicted in museums. This is because broader socio-politics have an influence on participation in relation to BIPOC communities. We reside in an era wherein the subaltern has spoken (Spivak, 1988). Emblematic of this are the strides made by Indigenous groups to combat structural inequalities by influencing policy making. For example, to address the problem of misrepresentation and exploitation of the Sámi culture, the Sámi parliament in Finland adopted ‘Principles for Responsible and Ethically Sustainable Sámi Tourism’ in 2008 with the goal to “terminate tourism exploiting Sámi culture and to eliminate incorrect information about the Sámi distributed through tourism” (2018, p.5). Museums fall within the broad umbrella of the tourism industry, hence the reference to tourism. Similarly, in Norway, the Sámi “established a national Indigenous parliament, the Sámediggi, which represents Sámi from all parts of the country, provides limited jurisdictional authority in areas such as language, culture and education, and has close links with departments of the Norwegian government” (Wilson & Selle, 2019, p.4). When talking about Sámi people in Norway, Hansen and Sørlie (2012) state that “Sámi today are forced to deal with at least two ‘worlds’: that of traditional Sámi culture and the Westernized Norwegian culture” (p. 27). However, from a political standpoint, despite the establishment of Sámi parliaments in Norway, Sweden, and Finland, one parliament that would unify the entire Sápmi does not exist, and the Sámi parliaments do not act in autonomy and are not viewed as sovereignty tools (Harlin, 2008; Lantto, 2010).

In line with the aforementioned political advocacy, various museums depicting Sámi culture are striving to create spaces for more accurate “internal dialogue about the Sámi identity” (Potinkara, 2020, p.2144). However, despite the aforementioned ground-breaking policy changes, scholarship on Sámi portrayals has, to date, not documented how such progressive policies manifest in novel approaches to participation in the context of museum exhibits focused on Indigenous culture, particularly communities located in European nations. In the wake of the multiple global movements for social justice, attention to these matters is important in informing knowledge regarding the agentic power of Indigenous groups (Buzinde, Shockley, Andereck, Dee, & Frank, 2017) but also in creating awareness about participatory practices (Buzinde, Manuel-Navarrete & Swanson, 2020) pursued by museum officials to advance principles of justice and diversity. Thus, bridging the gap in the literature, this paper draws on the theoretical framework proposed by Goodnow (2010) to explore participatory approaches deployed by museums that feature entire or partial exhibits on Indigenous Sámi culture. Specifically, the purpose of this study is to explore museum officials’ perceptions of participation with Sámi communities portrayed in their museums. This research responds to Kinsley’s (2016) call for scholarship that moves beyond a reductivist focus on increased attendance and instead examines the processes of participation with a local community so as to better understand issues of justice and inclusion.

Literature Review

The representation of Sámi Peoples in museum exhibitions throughout the years, facilitated the spread of stereotypical images of the Sámi culture that implied that they were “inferior” and “primitive” (Potinkara, 2020; Silvén, 2014), and even “people without history” (Kalsås, 2015, p.33). In relation to this, it is important to mention the forced assimilation processes faced by Sámi Peoples, following the partition of Sápmi and the establishment of the Nordic countries, which affected their cultural, political, and economic lifestyle (Lantto, 2010; Minde, 2005). Sámi people were considered inferior and uncivilised, Sámi languages were prohibited in schools, and cultural practices and traditions were banned (Hansen et al., 2016; Minde, 2005). Known as Norwegianization in Norway, this assimilation process weakened Sámi identities and livelihoods, and the discrimination and stereotypical framings affected the well-being of Sámi people (Minde, 2005; Pettersen & Brustad, 2013). In relation to the museum discourse, it is essential to mention that numerous objects and artifacts have been appropriated by the dominant culture and displayed, outside of Sápmi, within the collections of national museums (Potinkara, 2020; see Gaup et al., 2021). The discussion of Sámi Peoples portrayal necessitates a conversation about the museum and participation therewithin.

Over the years, scholars have problematized the concept of the museum and its social role (Brown & Mairesse, 2018). In the early 1970s, museums were narrowly characterized by values of “custodianship, preservation and interpretation” and with time this framework changed to encompass “the needs of the community located at [the museum’s] core” (Brown & Mairesse, 2018, p.529). The International Council of Museums (ICOM), a world-renowned agency in the field of museology, defines the museum as:

…a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment (ICOM, 2007, online).

It is important to note that many renditions of the aforementioned definition were devised and although generally accepted the above iteration is once again under scrutiny. Plans by ICOM members in 2019 to make changes to this definition were postponed to 2022. A major factor in the recent request for revision is attributed to the fact that many museologists and professionals want a definition with more focus on the importance of participation, social inclusion and community development (Brown & Mairesse, 2018). The proposed changes will better align with the growing body of literature on participation in museum experiences, which have become central to museum studies (Boast, 2011; Clifford, 1997; Davies, 2010; Lynch & Alberti, 2010; Lynch, 2011; Morse et al., 2013; Mygind et al., 2015; Onciul, 2013; Peers & Brown, 2003; Robinson, 2017; Sandell & Nightingale, 2012; Simon, 2010; Taxén, 2004). Although extant research includes a broad array of activities that denote participation, there is a general consensus that it entails external focused (e.g., museum reaching out to community members) as well as internal focused tasks (e.g., community members narrating stories of their lived experience to complement the official museum narrative) (Davies, 2010; Goodnow, 2010; Simon, 2010).

Morse et al. (2013) indicate that participation is an intricate task because of “the complexity of individual and group behaviour and motivation, as well as idealising some forms of participation over others” (p.102). In her book titled The Participatory Museum, Simon (2010) makes a similar argument. She claims that “there’s no single approach to making a cultural institution more participatory” (p.184) and that different situations require different levels of participation. She presents her own model, based on the Public Participation in Scientific Research (PPSR) project, which comprises four categories: contributory, collaborative, co-creative and hosted. In this model, the categories are not seen as “progressive steps towards a model of ‘maximal participation’” (Simon, 2010, p.188), instead the desired outcomes of the project guide the valuation of a participatory process.

The notion of museum participation is of particular interest when one considers the depiction of ethnic minority groups. At the end of last century, the new postcolonial angle in museology was advocated for and more inclusive programming and shared curatorship, especially in museums displaying Indigenous culture, was strongly encouraged (Boast, 2011). This statement is supported by Clifford (1997, p.192), who identifies the museum as “a contact zone” (a concept coined by Pratt (1991)). Pratt (1991) defines the contact zone as “social spaces where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power, such as colonialism, slavery, or their aftermaths as they are lived out in many parts of the world today” (p.34). Clifford (1997) argues that, in the contact zone, different cultures and perspectives come in contact, the one-way dialogue is replaced by different narratives, and “their organizing structure as a collection becomes an ongoing historical, political, moral relationship – a power-charged set of exchanges, of push and pull” (p.192). This view has been critiqued by scholars (Ashley, 2005; Bennett, 1998; Boast, 2011; Lonetree, 2006) who argue that contact zones are not necessarily sites of equal reciprocity and that despite the best intentions, they are places where “the Others come to perform for us, not with us” (Boast, 2011, p.63). Onciul (2013), proposes the notion of ‘engagement zones’, adopting the idea of contact zones, but incorporating what Clifford’s (1997) vision does not, inter- and cross-cultural relationships within the community. Engagement zones, in fact, “enable consideration and exploration of internal community engagement, culture, and heritage prior to and beyond the experience of colonialism and allow for the indigenization of the process” (Onciul, 2013, p.83). Given the insignificance of prioritizing the monetization of museum related participation, the abovementioned practices must be motivated by ethical considerations. This is in accordance with Principle 6 of ICOM Code of Ethics, which implores museums to “work in close collaboration with the communities from which their collections originate as well as those they serve” (ICOM, 2017, p.33). However, ICOM does not provide any guidelines on best practices for institutions to follow, which is why theoretical guidelines like Goodnow’s (2010), which are grounded in practice, are vital to the assessing of situations and implementation of needed changes.

Methodology

This study draws on a constructivist paradigm to obtain in-depth insights into the concept of participation as perceived by museum officials operating in institutions that portray Indigenous Sámi culture. Semi-structured interviews were employed in this study in order to facilitate “a conversation with [the] purpose” (Lune & Berg, 2017, p.65) of gathering information, uncovering hidden meanings and enabling participants to express their own opinions and views (Brinkmann, 2013). According to Creswell and Poth (2018, p.45), qualitative methods, such as interviews, can allow for traditionally silenced voices to be heard. Porsanger (2004) underlines the importance of placing Indigenous People’s interest and knowledge at the centre of research, especially when conducted by non-Indigenous scholars. The need for an ethically and culturally appropriate approach in Indigenous research must be supported by the inclusion and collaboration with members of the Indigenous community “not as objects but rather as participants” (Porsanger, 2004, p.112). Accordingly, researchers have the responsibility to report back to the people (Porsanger, 2004), as was done in the current study.

Interview questions were drawn from existing literature on museum participation and Indigenous studies in order to inquire about: the museums’ collaborations with Sámi communities; the community participants and the tasks they are engaged in; and, the challenges faced and successes gained by museums officials engaged in these practices. Participant’s responses were mapped onto Goodnow’s (2010) framework to glean insights into the types of participation activities deployed by museums in their portrayal of Sámi culture. The interviews were conducted in February through March 2021. The Zoom online platform was utilised to account for constraints imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. This study was approved by a University Institutional Review Board (IRB). Participants were selected using a purposive sample based on a Google search of Sámi owned and non-Sámi owned museums. This was later corroborated with museum lists provided by Destination Marketing Organizations (DMOs) in Norway. The Sámi owned museums located include: the Sámi Museum in Karasjok, Kautokeino Municipal Museum, Kokelv SjøSámiske Museum, Ä′vv Skolt Sámi Museum, Tana Museum and Varanger Sámiske Museum. The non-Sámi owned museums include: Arctic University Museum of Norway, Holmenes SjøSámiske Farm (which is part of Nord-Troms Museum), Norsk Folkemuseum, Kulturhistorisk Museum, Røros Museum and Alta Museum.

Thematic analysis, which is described by Braun and Clarke (2006) as “a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data” (p.79) was used in this study. Braun and Clarke (2006) identify six phases for conducting thematic analysis, which were followed in the current study. The first step was to get familiar with the data collected, by reading it multiple times and trying to find patterns. This first phase also required the transcription of the interview data. The second step entailed the generation of initial codes and this was followed by the construction of themes. In this latter step, the researchers combined multiple related codes together within an overarching theme. The following phase entailed reviewing the themes whilst ensuring that each theme coherently connected to its related codes as well as to the entire data set. The researcher defined and names the themes, by writing a short description and the scope of each theme, as a way to guarantee clarity and precision. The last step involved the creation of “a concise, coherent, logical, non-repetitive and interesting account of the story the data tell – within and across themes” (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p.93).

In terms of positionality, the authors are not members of the Sámi community nor are they citizens of Norway. Rather they are lifelong scholars with interests in issues of representational politics. The lens we adopt facilitates interrogations of societal structures that have relegated certain groups to the periphery. The goal is not to highlight victimhood, albeit important, but rather to showcase the agency and important strategies taken by various individuals to advance the ideals of a more just and equitable society.

Findings

The responses to the interview questions are presented using Goodnow’s (2010) participation categories, namely: access; reflection; provision, and structural involvement. All of Goodnow’s participation categories resonated in the data, irrespective of whether the museum was owned by Sámi or non-Sámi. The subsequent section elaborates on the details of each category.

Access

The pattern related to access denoted in the findings was associated with language and culture as key criteria implemented by museums to ensure that the institution was accessible to the local Sámi community and any Sámi visitors. Language can indeed play an important role in increasing access for external individuals and in facilitating the interpretation of exhibited materials (Coxall, 2000; Kelly-Holmes & Pietikäinen, 2016). At the same time, language practices can make participants feel welcome and comfortable (Dawson, 2014). As is indicated in the excerpts below, the intentional use of Sámi language in both Sámi and non-Sámi museums was mentioned several times in the interviews:

We are a Sámi museum, Sámi owned…So, everything is Sámi. Sámi is the official language [of the museum]. (Kokelv SjøSámiske Museum – Sámi)

Everything we have registered at our museum collections…we register them first in Sámi language. So, you can just write Sámi…and search in the search engine…in Sámi, you will find them. (Kautokeino Municipal Museum – Sámi)

…we try, all the time to connect the Sámi language, where it is possible…we always have the eye on where is the Sámi language here? (Tana Museum – Sámi)

…we will be working more…to manifest the Sámi language in the museum, where we don’t have very much to be proud of just now. We have an audio guide that is translated, and available in Southern Sámi. (Røros Museum – Non-Sámi)

The degree of use differed but interviewees recognised the responsibility of making the Sámi culture relevant and accessible through varying uses of Sámi language. By focusing on the importance of amplifying the Sámi language, which is currently regarded by UNESCO as endangered (The Arctic University of Norway, 2019), the museums protect and promote the intangible cultural heritage of the Sámi community (Loach et al., 2017). The focus on weaving in language is profound because as Minde (2005) argues “the state’s [historic] efforts to make the Sámi (and the Kven) drop their language, change the basic values of their culture and change their national identity, have been extensive, long-lasting and determined” (p.20). As a result of colonial language and education policies, the use of Sámi language was prohibited in schools and Sámi youth were forced to attend boarding schools to learn Norwegian (Heidemann, 2007; Minde, 2005).

According to Goodnow (2010), the development of cultural programs has the objective of bringing a wider audience to museum experiences and consequently of increasing access. In the exemplary quotes below, the museums became locales wherein the local community members were invited to join in different cultural activities. These practices not only increased visitation, but also made the public aware of the museum as ‘open to the community’.

We have courses in [traditional] plant colouring and embroidering… (Ä’vv Skolt Sámi Museum – Sámi)

People only come if they’re interested. So, we have tried to hold something about the [traditional] fisheries, because otherwise the men won’t come, and then we started a project with the [traditional] costumes, we had a lot of women coming, and they come also from the neighbouring municipalities driving 150 kilometres, just to meet up. (Varanger Sámiske Museum – Sámi)

We always talk about how we can get people to be more active. What are they interested in? What abilities do they have? And what kind of cultural arrangements do we need to have them be a part of it… (Norsk Folkemuseum – Non-Sámi)

Thus, access was a concept that all interview participants had experience implementing in a way that facilitated ownership amongst community members and that was principally premised on advancing activities related to language and culture.

Reflection

The pattern related to reflection denoted in the findings was associated with advocacy. That is, the willingness of museums to be advocates for change. According to Goodnow (2010), reflection undertaken by museums is of importance to marginalised, invisible, or silenced groups, and can inspire awareness, creation and reframing of the role of museums within society. In terms of advocacy, both Sámi and non-Sámi museum representatives acknowledged the importance of conveying the Sámi narrative in an honest and ethical manner while also breaking down stereotypes and addressing cultural discrimination. For instance:

I think, to understand the Sámi history, you need to…understand the colonialisms that happened and are still going on and it’s our duty to tell that story, so we are trying to tell it, but not in a negative way. It’s easy to earn money on the Sámi culture and tradition if you just want to make it interesting. But it has to be authentic, it has to be the truth, we can’t just romanticise, you have to have some responsibility, that is the truth and not these pictures everybody else want us to be. It has to be us. (Sámi Museum in Karasjok – Sámi)

I think every sensible Norwegian today would be ashamed of the politics of Norway, in the late 70s in Norway at least. Of course, you very often end up, on the completely other side, when you have issues with the cultural appropriation. It’s good to find a way [to] communicate with minority groups. It’s definitely very important to do that also on their own terms and to not be defined by the museum, as part of the majority society. (Røros Museum – Non-Sámi)

The museum officials were adamant about the fact that, to understand the present, one needed to comprehend the past experiences of colonialism as well as acknowledge that it was an era during which Indigenous Peoples and their culture was silenced. Accordingly, museum officials viewed the role of the museum as giving voice to Sámi culture and identity while correcting any misrepresentation perpetuated by dominant culture. In many ways they worked to reverse the hegemonic practices that had traditionally been associated with the museum-related ‘engagement zones’ (see Onciul, 2013) and thus they took steps to advocate for more just portrayals of the Indigenous community (see Boast, 2011).

We need to give a true picture of the Sámis today. I always think that’s very important because if we need to fight against the stereotypes, we need to tell the truth about the Sámi today. (Norsk Folkemuseum – Non-Sámi)

…we have this policy of ‘we are going to tell our own stories’ nobody else are going to tell us what we want to say. We have to be us and not others, if we are going to be… true to ourselves. We haven’t blown ourselves into every idea that is coming, and people say, “well, you are boring, and then we are not coming with the tourists…” Our main focus needs to be ourselves, so it’s more important to do the work that we need to do, to make sure that the generations to come are going to have these possibilities that we have. It’s important that we are…lifting the Sámi people proudness…making it stronger, and that is the most important things that we can do as a museum, to be a part of making the next generation strong in their identity, in their culture, in their connection to their own history. (Sámi Museum in Karasjok – Sámi)

We want to show what the Sámi think they are, what the Sámi know they are. So, it’s not supposed to be an outsider view on the Sámi people, it is the Sámi talking about their culture, their history. It’s quality check too. So it’s very important that we are not portrayed as a Norwegian or a Western world museum that just takes the Sámi and put it into the Western idea. We are Sámi museums. (Kokelv SjøSámiske Museum – Sámi)

… to be a museum that is not only taking care of the objects, but we’re also taking care of the way of thinking, the way of living and the way of practicing our culture…we also need to get to the next generations, to be proud of who they are…the work that we’re doing by communicating the possibilities in Sápmi, it’s also quite important for the youth, that they will see that it’s a lot of possibilities and they have a world of different things they can be doing and working with and be a part of saving our history and traditional way of being for the generations to come. (Sámi Museum in Karasjok – Sámi)

Truth telling in this context entailed narratives of the people told by the people in whatever way they deemed appropriate. There was thus a pronounced level of agentic power in participants’ description of advocacy, as it relates to reflection.

Provision

The pattern related to provision denoted in the findings was associated with artefacts provided by community members and storytelling activities led by members of the Sámi community. According to Goodnow (2010), participants’ contribution under the category of provision can help museums disseminate a better understanding of the portrayed culture and the history of the community in question. It can also aid in moving beyond the official story, by complementing it with a more personal narrative. In the excerpts below, the interviewees share numerous examples of how Sámi community members contribute to the museum exhibits/installations:

We have this project, where the Sámi people can participate throughout all the processes of collecting objects, telling stories, arranging the exhibition space. … We have a lot of objects, you know, the Sámi collections…it’s very static. So, collaboration and connection with local Sámi people also brings information to the objects, and makes our history richer. (Alta Museum – Non-Sámi)

The stuff that we get, the items, objects, the photos, the stories and the immaterial culture, they come from the local community mostly, and they come from the coastal Sámi, sea Sámi. The local community is easy to ask for help, they’re interested in what’s happening at the museum. They give us their views, their ideas…ideas for projects. (Kokelv SjøSámiske Museum – Sámi)

We have a very high standard of trust from the society, the society trusts the museum. And they give us a lot of objects, new objects. (Kautokeino Municipal Museum – Sámi)

The collections we have, have been burned a couple of times. The first time was the war, and the second time was when the storage area where they had their collections burned. They saved a lot of the objects, but the descriptions were lost…a lot of what we have, is given from the people in Karasjok, that have given it to the museum. (Sámi Museum in Karasjok – Sámi)

The involvement of local community members in defining museum exhibits is becoming a popular practice (Davies, 2010). In addition to the provision of tangible objects, museum officials also spoke to the interpretive role (as docents of sorts) enacted by local community members within the museum exhibits. For example:

We participate in different areas, where we present our plans or what we do and so, in that way, the Sámi people have the opportunity to respond to what we do…The exhibition was contemporary, and seven people were portrayed through interviews and photographs. They were Sámi people…In the exhibition the Sámi people, they themselves were the speakers, and that is an important way of doing this. (Røros Museum – Non-Sámi)

Sometimes, as is indicated in the excerpt below, locals enacted impromptu interpretive roles:

…locals will often come and eat and have a cup of coffee and if somebody, a tourist or somebody comes in and asks something, they would sit there and would hear what the conversation is and will say “well, I know that person or I know that thing…” and so they would engage them if there is a conversation, even though they just stopped for coffee. (Varanger Sámiske Museum – Sámi)

The above excerpts are illustrative of how allowing community members to participate via provision of physical artefacts and/or storytelling facilitate the emergence of multiple narratives related to the lived experiences of the Sámi community (see Boast, 2011; MacDonald, 2006).

Notably, museum officials also mentioned that caution was needed when involving Sámi community members in the narration of the past because the process can be emotionally challenging for some.

You have the problem that sometimes some people might not want to collaborate or tell people, tell the museum about history, about their personal history, family history, because it’s still so close…It’s still quite raw…so there’s a lot of things that might trigger reactions from people. It might be stuff that their parents never talked about. A lot of people might not know their personal and family history, because their grandparents don’t want to talk about it. So that’s a challenge as well, and sometimes that challenge simply can’t be overcome. (Kokelv SjøSámiske Museum – Sámi)

So many mixed feelings from elders being ashamed, not willing to share the stories and wanting still to hide it because of the Norwegianization process that we had a long time ago…young people [are] more proud and much more…able to share it. (Alta Museum – Non-Sámi)

The younger generation are certainly more distant from the colonial era and this may explain the above comment. Similarly, over the last few decades, there has been, amongst the younger generations, a stronger need to affiliate themselves with Sámi culture (Johansen & Mehmetegolu, 2011). Suffice it to mention however that locals were generally willing to share their artefacts, tangible and intangible, with museums and this amplifies the participation category of provision.

Structural Involvement

The pattern related to structural involvement denoted in the findings was associated with employment within the museum of community members. Goodnow (2010) argues that structural involvement can occur on two different levels: individuals from the community are appointed as members on an advisory board, leaving the final decision to curators and directors, or community representatives who might hold curatorial and/or directorships. Notably, with two exceptions the majority of the interviewees, located at Sámi and non-Sámi museums, identified themselves as Indigenous People, from Sámi communities who held positions, such as leaders, curators, conservators, and managers. For example, comments such as the ones below were shared in the interviews:

I am the curator and I have the responsibility of caring for the Sámi collection…I am North Sámi, I am from Kautokeino, and I speak North Sámi, but I understand Lule Sámi and Inari Sámi too…I was raised in a reindeer herding family. (Norsk Folkemuseum – Non-Sámi)

I’m the leader of the museum…for almost eight years now, and I am a Sámi. I grew up with Sámi culture, language, clothing, life, way of living. (Tana Museum – Sámi)

[I am the] Conservator…I [am] a mixture of Sámi and Kven. Kven it’s a national minority here and Norwegian. So it’s a mix. (Holmenes – Non-Sámi)

I’m the museum leader…I’m Sámi. (Ä’vv Skolt Sámi Museum – Sámi)

I have been hired as a curator…[I am] from the Northern Sámi group, the local group here. I live in the community, and I am a farmer, and a handcrafter. (Varanger Sámiske Museum – Sámi)

The representation of Sámi museum employees is pronounced and needed to ensure authentic portrayals of the lived experiences of the communities. These affirmative action procedures inspire transformational change at the structural level which can have profound impact at the discursive level related to the museum exhibits (see Onciul, 2013). Interestingly, as is indicated in the quote below, one respondent linked the employment of Sámi employees to authentication:

I don’t think we would have any credibility as a Sámi museum if we didn’t have Sámi people working here and because there’s something about… when tourists come, they’re not so interested maybe in our exhibition handcrafts, they’re more like, you know, “what is it really like to live here?”, and “do you speak the Sámi language?” and “what does it mean to be Indigenous these days?”. Those are questions that you can answer if you’re a local … (Varanger Sámiske Museum – Sámi)

Non-Sámi museums also acknowledged the necessity of having members from the Sámi community employed in the museum.

We always need to have a Sámi person as one of the summer employees. We need to have Sámi (Norsk Folkemuseum – Non-Sámi)

We cannot say that we have checked off the Sámi involvement or make it legitimate by having one from the Sámi Nation working in the museum. … I think, for that reason, not as an alibi, but you just need to have someone who actually could be able to point that this- this works, this doesn’t because it’s not always given that we would know or understand that. (Røros Museum – Non-Sámi)

Remarkably, the lack of qualified Sámi people with museum experience, especially curatorial experience, was mentioned as an impediment experienced by Sámi and non-Sámi museums.

…the first Sámi exhibition of 1975, still present in our venue, the main designer was the famous Sámi artist Iver Jåks. In the second permanent exhibition Sápmi en Nasjon Blir Til the curators were non-Sámi. In the recent smaller and temporary exhibitions, we pay attention to involve Sámi curators, although one must admit that there aren’t many available on the “market”. We do not have permanent curators nor conservators in our museum. (Arctic University Museum – Non-Sámi)

The lack of Sámi people with professional experience in museology becomes an obstacle for these institutions. There may be socio-political reasons that prevent Sámi community members from pursuing jobs in museums or even education in museology but exploration of those matter was beyond the scope of this study. It is important to note however that employment of Indigenous community members within dominant culture spaces like museums was a profound example of structural involvement, as a form of participation.

Discussion

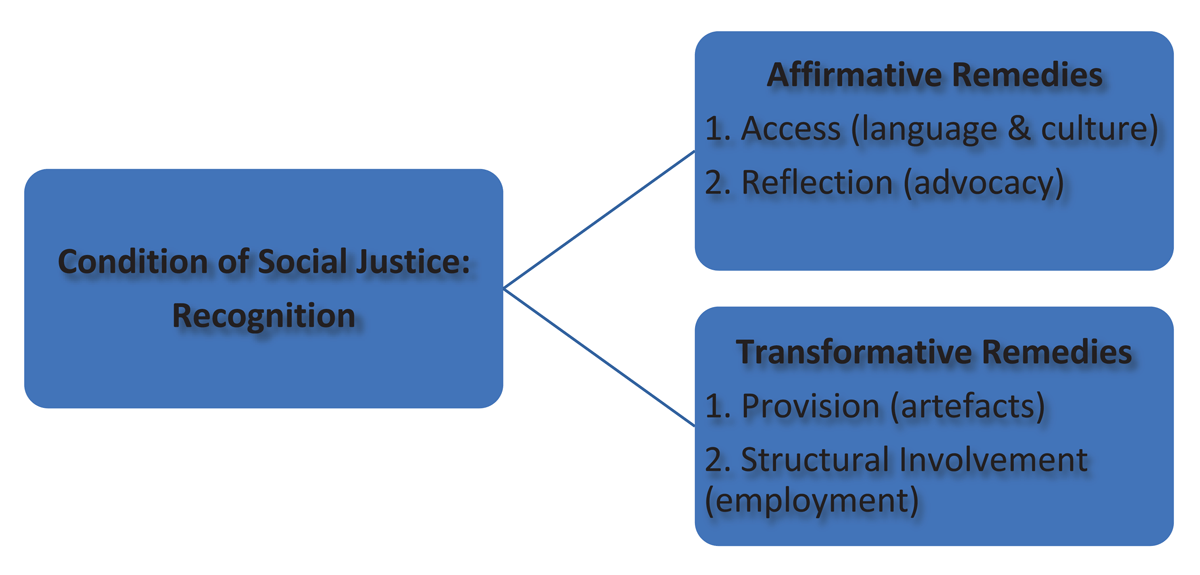

The interviews with museums officials shed light on their perceptions of participation and on the current participatory practices undertaken in their museums. At a micro level, the emergent examples augment knowledge regarding the various forms of participation practices deployed by 21st century museums that are depicting Indigenous cultures. On a macro level however, given the current era of heightened human rights movements, these participation practices which are directly related to the representational politics of portraying colonized communities, have to be interpreted from a social justice stance. In fact, as is shown in Figure 1, one of the key contributions of this discussion section is that it directly links the social justice concept of recognition discussed by Fraser (1995, 2007, 2008) and adapted by Kinsley (2016) to the dimensions of participation (access, reflection, provision, and structural involvement) outlined by Goodnow (2010). Fraser (1995, 2007) discusses many conditions of social justice. The most applicable condition to the findings of the current study is recognition, which is related to distributive justice, especially issues of “disrespect, cultural imperialism, and status hierarchy” endured by groups of the margins (Fraser, 2007, p.27). The term disrespect in Fraser’s work (1995) refers to practices of “being routinely maligned or disparaged in stereotypic public cultural representations and/or in everyday life interactions” (p.71). Therefore, cultural and symbolic injustices are complexly entangled with hierarchical, systemic, and institutionalised models that create cultural imperialism, inequality and misrecognition for a society or a group of people (Fraser, 1995, 2007; Keddie, 2012). In terms of recognition, participants in the current study spoke of the cultural domination Sámi Peoples have had to endure as well as the proliferation of stereotypical portrayals of Sámi culture. Participants were adamant in their conviction that these portrayals have to be dismantled (advocacy). They were also aware of the pivotal role that institutions like museums can play in reversing the image through education of the public.

Figure 1

Mapping Participation onto The Social Justice Condition of Recognition.

Within the condition of recognition, Fraser (2007) advocates for the existence of affirmative and transformative remedies (Kinsley 2016). Affirmative remedies strive to correct “inequitable outcomes of social arrangements without disturbing the underlying framework that generates them” (Fraser, 1995, p.82) whilst transformative remedies are “aimed at correcting the inequitable outcomes precisely by restructuring the underlying generative framework” (Fraser, 1995, p.82). Akin to the concept of multiculturalism, affirmative remedies “redress disrespect by revaluing unjustly devalued group identities, while leaving intact both the contents of those identities and the group differentiations that underlie them” (Fraser, 1995, p.82). By contrast, transformative remedies aim to achieve deconstruction and amend misrecognition by “destabilizing existing group identities and differentiations” (Fraser, 1995, p.83). According to Fraser (1995), this would not only benefit marginalized groups by empowering them, but also positively influence “everyone’s sense of belonging” (Fraser, 1995, p.83).

In terms of affirmative remedies, access and reflection, which manifested in the findings as language and culture and advocacy respectively, clearly showcase the steps undertaken by museum officials to deal with issues of inequity. For instance, as relates to access, participants’ comments related to language and culture highlight the inclusion of Sámi languages. This important practice accounts for the assimilation policies that prohibited the use of Sámi language and most importantly, it serves as a self-determination tool for the Sámi communities. According to Kelly-Holmes and Pietikäinen (2016), the inclusion or exclusion of certain languages in museums can influence visitors’ experience. The use of Indigenous languages can “challenge or reinforce existing linguistic and cultural hegemonies and stereotypes” (Kelly-Holmes & Pietikäinen, 2016, p.25) and it can also thwart or enhance linguistic revitalisation processes (King, 2001; Thorpe & Galassi, 2014). In the current study, participants’ active efforts to weave Sámi language into the museum exhibit was instrumental in celebrating multiculturalism, and uplifting Sámi culture and identity.

As relates to reflection, participants’ comments linked to advocacy highlight the various ways museum officials are advocating for the centrality of Indigenous voices within the official historical narrative presented in the exhibits. Accordingly, museum officials mentioned the importance of acknowledging the history of injustices endured by the Sámi communities as a necessary foundation from which to build a strong and clear message for future generations. This sentiment, much like the others, was shared by Sámi and non-Sámi museum officials. Participants also regarded their role in knowledge mobility as vital in the fight against discrimination and stereotypical depictions of Sámi culture. In essence, the findings related to access and reflection clearly showcase approaches undertaken by museum officials to problematize the current system of cultural dominance. However, and unlike the two categories discussed in the subsequent section, these aforementioned advances towards multiculturalism do not strive to deconstruct (or transform) the structure of the museum.

To move toward transformative recognition remedies, Kinsley (2016) provides the example of museums developing community advisory committees (CACs), which “are composed of community members who, through lived experiences, education or hobby have developed relevant expertise to an exhibition that is being planned” (p.484). The idea of CACs disrupts the traditional role of a sole curator, making the final decision, and instead distributes the responsibility to multiple members with different levels of expertise, resulting in the valuable process of co-creation (Kinsley, 2016). In line with Kinsley’s (2016) transformative remedies, the categories of provision and structural involvement, which manifested in the findings as artefacts and employment respectively, demonstrate efforts taken by museum officials to restructure institutional practices towards a more just and inclusive agenda. For instance, as relates to provision, participants spoke of the role of community members who are non-museum professionals contributing to the co-creation of a pluriversal official museum narrative through the provision of tangible (e.g., material donations) and intangible (e.g., storytelling from members of the Sámi community) Indigenous heritage. According to Goodnow (2010), collaboration between museums and the source community strengthens the status of the museum as an institution and amplifies the voice of the portrayed community (Goodnow, 2010). The objects shared in such collaborations are “more than just ‘things’ illustrating historical or cultural narratives, rather they can be re-identified as political resources in their own right given the cultural authority they have to represent or stand in for national and community identity” (Smith & Fouseki, 2011, p.8).

Despite lacking the curatorial and decision-making power that Kinsley (2016) observed in CACs, the provision category offers examples of museum officials striving to redress elements of misrecognition and disrespect endured by Indigenous communities, by involving the community and allowing them to share their lived experiences. For instance, the Sámi Museum in Karasjok eliminated texts or photographs within their exhibition, so as to give Sámi staff and local community members visiting the museum the opportunity to provide their own stories and anecdotes, by so doing personalizing the experience. This is what Lehtola (2018) refers to “as our histories” which “depict the local understanding of the past” (p.2). By directly using Indigenous voices, museum officials avoid the promotion of narratives filtered through Western viewpoints. As is eloquently mentioned by Sium and Ritskes (2013) the speaker “who does the storytelling, remains an important question in decolonization work” (p.iv) precisely because “Indigenous stories are a reclamation of Indigenous voice, Indigenous land, and Indigenous sovereignty (p.viii). From this vantage point the contributions of non-professionals to the official museum narrative were transformative remedies that broadened the number and type of people with authority to speak about the culture on display.

As it relates to structural involvement, participants’ discussed arrangements made to offer official employment within the museum, to members of the Sámi community. Structural involvement is perhaps one of the strongest transformative remedies (see Fraser, 1995) in terms of restructuring capacities evident in the data. Similar to Kinsley’s (2016) example of CACs, the findings of this study indicated that members of the Sámi community were appointed to official museum roles as curators, directors, or conservators within Sámi museums. Some participants argued that the Sámi lived experience is vital in the cultivation of deep links to the Sámi culture. From this vantage point, employment of Sámi Peoples in the museum context can capitalize on Indigenous Knowledge (IK) to vastly enrich the narration of Sámi culture. The manifestation of social justice conditions such as recognition evident in the current study is indicative of the postcolonial shift undertaken by the museums that were engaged in this research (see Boast, 2011; Onciul, 2013). Arguably, this shift will become more prevalent in coming years as more Indigenous groups and related allies continue to demand for corrective measures to human rights related matters.

Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to explore participatory approaches deployed by museums that feature Indigenous Sámi culture. Specifically, this study examines museum officials’ perceptions of participation with Sámi communities portrayed in their museums. Focusing on Sámi as well as non-Sámi owned and operated museums, this study draws on the theoretical framework proposed by Goodnow (2010), which classifies participation in museums as premised on the existence of four dimensions: access; reflection; provision; and, structural involvement. The participation categories identified by Goodnow (2010) resonated in the findings and showcased activities unique to the collaborations with Sámi community members. A key contribution of this work is the connectivity between the emergent accounts and the condition of social justice referred to by Fraser (1995, 2007, 2008) as recognition. According to Fraser (1995), the state of recognition tackles cultural and symbolic injustices such as cultural domination, nonrecognition, and disrespect, to name a few. Corrective measures that can be employed include affirmative remedies, which attempt to redress unjust circumstances and outcomes without undermining the system they are part of whilst transformative remedies reframe the system to combat injustices (Fraser, 1995; Kinsley, 2016).

Although exploratory in nature, the current study engages broader debates on social justice. It does so by illustrating how museums whose exhibits entirely or partially feature Indigenous culture are reversing dominant narratives and practices so as to create more inclusive spaces (affirmative remedies) but also how these institutions challenge structural impediments (transformative remedies). The inclusion of Sámi languages within the exhibits (access) as well as the advocacy focused on grounding the historical lived experiences of Sámi Peoples (reflection) were quintessential examples of affirmative remedies undertaken by museum officials. By contrast, the allowance of tangible and intangible heritage artefact contributions from Sámi community members (provision) as well as the employment of Sámi Peoples in the museum exhibiting Sámi culture were exemplary of transformative remedies deployed (structural involvement). All participants agreed that it is important to center the Sámi voice in the museum context and to articulate a historic narrative that highlights their oppression and triumphs. Museums have been critiqued for adhering to stereotypical portrayals of Indigenous groups as well as their disengagement with the Indigenous communities whose culture is exhibited. The current study showcases how museums in Norway that feature Sámi culture have approached the notion of participation and in so doing have taken steps towards certain forms of social justice.

Future research on museum participation is certainly needed to further augment knowledge on this matter. Perception of Indigenous community members, as well as those of museum visitors, can shed light on how participation practices are received by these two groups. In an era wherein Black, Indigenous and other groups of color (BIPOC) are actively advocating for equitable representation and decolonial approaches, it will be vital to have access to scholarly investigations that can continue to inform the incorporation of inclusive and just practices within museology.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.