1. Introduction

In archaeology, records about architectural monuments are often represented as unstructured texts written in natural language and disseminated across various platforms. This scenario can hinder the findability and accessibility of data. To effectively analyse the large volume of existing data, the integration of datasets from multiple sources and research communities is often necessary. Over recent years, the importance of leveraging data management tools, along with associated metadata and standards formats, has come to the forefront for representing information formally. As a result, there has been a growing emphasis on standardised access to such information to make it understandable to both humans and machines.

When we talk about the handling and storing of information in computer science, knowledge bases (KB) and databases (DB), although complementary, are addressed separately. In essence, ontologies (a.k.a. as knowledge bases) describe certain realities so that domain knowledge can be represented by them (Gruber 1993) and traditionally focus on high-level reasoning to make inferences or to check for information consistency. While a number of languages and methods have been developed to standardise information, the CIDOC-CRM ontology is one of the most widely used and has become an ISO (ISO 21127:2006) standard in the cultural heritage field. As a high-level, event-centric ontology, CIDOC-CRM provides definitions and a formal structure for describing implicit and explicit concepts and relationships in cultural heritage. The CRM (version 7.2.1) consists of 81 hierarchically organised classes and 160 properties (Bekiari et al. 2021).

Different types of knowledge can be found in a knowledge base, including rules, facts, definitions, statements, and primitives. The information can be represented as a graph, consisting of nodes and relationships, which can also hold instances (i.e., the population of the ontology). Recently, Knowledge-Graphs (KGs) have received significant attention, especially for their application as an inference motor. In contrast, database technology optimises data organisation for efficient storage, management, and retrieval. The development of graph databases (GDB), a type of NoSQL database that optimises element-driven data browsing instead of batch processing as with traditional relational databases, presents opportunity for new knowledge driven use cases.

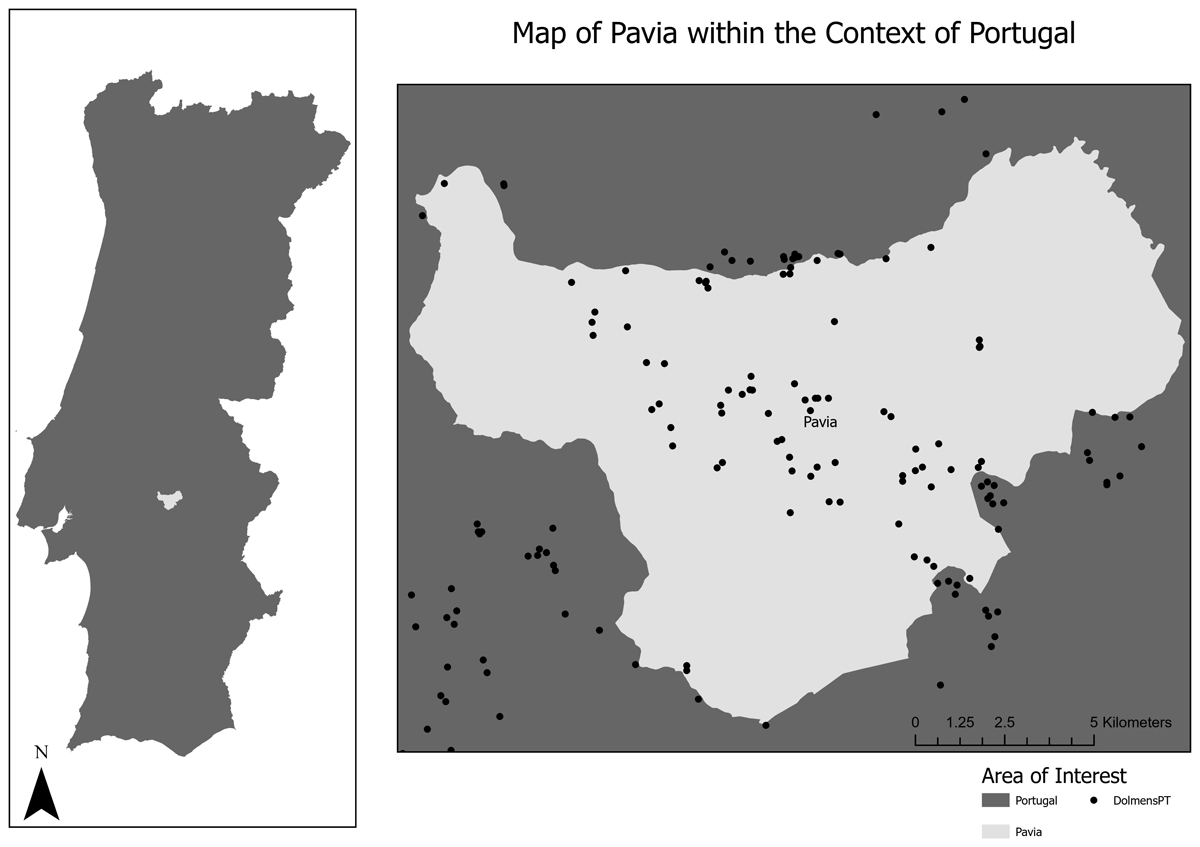

As part of the automated recognition of archaeological monuments in remote sensing images, a knowledge graph based on CIDOC-CRM was implemented so that architectural components of dolmens can be represented as nodes. The case study was based on dolmens located in Pavia, a city in the region of Alentejo, Portugal (Figure 1). The graph model was implemented using the Neo4j graph database as a Labeled Property Graph (LPG) (Miller 2013). Our LPG uses the classes and properties defined in CRM as labels and types. As far as we know, none of the related research works use a native graph database (NGDB) to represent architectural components of archaeological monuments to apply inference tools to derive new knowledge – or even to integrate in approaches for the automation of archaeological monuments recognition, which is the ultimate goal of the present project research. This paper is structured as follows: first, the definitions of the main elements discussed are presented, specifically, we define why to use native graph databases and show Neo4j’s advantages for the representation of knowledge. Then, an overview of the work in the area is presented, followed by the implementation of the graph model. Lastly, we present the conclusion that includes a summary of expectations for the future.

Figure 1

Map highlighting Portugal with a detailed inset of the Pavia region, situated within Mora in the Alentejo area.

2. Native-GDB Explanation

2.1. Why use NGDBs

Graphs highlight relationships between items using vertices (nodes) to represent concepts and edges to denote the connections (relationships) between them. These relationships, just as vital as the data itself, facilitate efficient data exploration. GDBs are specialized systems designed for managing such interconnected data, enabling the construction of predictive models and pattern detection (Stanescu 2021).

One approach to exploring data connections is through Labeled Property Graphs (LPGs). In LPGs, both nodes and relationships come with a unique ID and a set of key-value pairs, or properties (Robinson, Webber & Eifrem 2015). This gives nodes and relationships an internal structure, allowing for compact queries when compared with the atomic-node RDF graph structure, which presents more expanded and detailed data representations. The LPG model allows queries involving multiple levels of relationships between instances to be run easily (Stanescu 2021).

The terms native and non-native databases can be used to describe graph databases. Non-native GDBs, instead of being specifically engineered for graph data, use relational databases, columnar databases, or other general-purpose databases. Performance and scalability are affected by graph data stored in non-graph storage. In contrast, NGDBs are tailored for graph data, ensuring efficient storage and rapid data traversal performance using index-free adjacency – that is, they store the connections between connected entities and nodes on disk (Robinson, Webber & Eifrem 2015). Although improving traversal performance, native graph processing makes some non-traversal queries difficult or memory-intensive. Using an NGDB, the focus is on efficient storage, querying and fast traversals across the connected data (Costa, Freitas & da Silva 2022; Robinson, Webber & Eifrem 2015).

2.2. Neo4j

The Neo4j database is an NGDB based on properties, distinguished by its query language – Cypher. Cypher is a systematised translation of the relationships between nodes and edges into queries. It relies on relatively expensive patterns to operate which, when used properly, can yield results not available for classic database engines (Zaniewicz & Salamończyk 2022). As well as its powerful query language, Neo4j has a wide range of advanced data manipulation libraries (APOC). Neo4j allows users to link disparate datasets quickly and easily by not requiring a rigid schema. Its high level of functionality and Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation and Durability (ACID) compliance has earned it a dominant position in the market. When compared with other NGDBs, Neo4j consumes less memory for processing (McColl et al. 2014), performs better through indexing techniques for query retrieval performance, and obtains the best results with traversal workloads (Jouili & Vansteenberghe 2013). Graph databases such as Neo4j are not developed to work well with basic graph patterns and atomic lookups (Hernández et al. 2016) or to deal with search based on a limited number of relationships (low number of JOINs in SQL databases) (Stanescu 2021). However, they are ideal for applications that require queries traversing several levels of relationships between data (Stanescu 2021). For example, with Cypher, patterns in graphs can be found easily (Jouili & Vansteenberghe 2013).

3. Related Literature

We can find extensive literature on using or showing how to use the CIDOC-CRM (Bekiari et al. 2021) to represent building and architectural remains in archaeology (Carlisle et al. 2014; R Garozzo et al. 2017; Gergatsoulis et al. 2021; Hansen & Fernie 2010; Ronzino et al. 2016; Santos et al. 2022) as shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Description of reference, approach and focus of each research that used as schema model the CIDOC-CRM definition, specifically targeting immovable archaeological heritage.

| REFERENCE | FOCUS |

|---|---|

| Hansen & Fernie (2010) | Describes CARARE metadata schema. The schema focuses on the record of detailed description of heritage, events, and online digital resources. |

| Carlisle et al. (2014) | Documents and share the experience and benefits to incorporate CIDOC-CRM standards into the design of Arches an open source software platform, geospatial information system for heritage inventory and management. |

| Ronzino et al. (2016) | Presents CRMba an extension of CRM to encode metadata about the documentation of archaeological buildings. |

| Gergatsoulis et al. (2021) | Uses CRM and CRMba to represent archaeological buildings derived from fieldwork (records, their provenance and images). |

| Santos et al. (2022) | Uses CRM to represent megalithic monuments – focusing on the megalithic concepts at a granular structural level. |

| Garozzo et al. (2017) | Presents a Cultural Heritage Tool based on Ontology (CulTO) for supporting the modeling of cultural heritage buildings (religious historical building) to develop high-level applications for data curation, retrieval and classification. |

| Garozzo et al. (2021) | Presents an automated hybrid approach (DL-KB) to automatically classify and retrieve photo data. The ontology (CulTO) was used to guide the process of generating synthetic images (GAN: Generative Adversarial Networks) and thus train the DL system. |

As observed, in most of the published works CRM is used for inventorying, integrating, and managing cultural data and sources, as well as semantic querying and retrieval of cultural data, with interoperability being the main concern. The majority of these research works use SQL (Carlisle et al. 2014) or NoSQL models. The latter mostly employs the Resource Description Framework (RDF) and/or Web Ontology Language (OWL) (Garozzo et al. 2017; Garozzo et al. 2021; Gergatsoulis et al. 2021; Santos et al. 2022). While several studies have explored the use of NGDB to implement knowledge graphs, few have done so using CIDOC-CRM as a foundation (Costa, Freitas & da Silva 2022; Koch et al. 2019). To our knowledge, none of these efforts, using NGDB with CIDOC-CRM, have been dedicated specifically to the representation of immovable cultural heritage and, instances and relationships analysis, within the realm of archaeology. Furthermore, these existing works do not focus on the potential for pattern analysis and inference on the information represented as instances.

4. Case Study

This case study uses information on megalithic monuments that were built between the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods in Portugal. The first proto-megalithic tombs were constructed in the interior of the Alentejo region around 5000 BC (Monteiro-Rodrigues 2011). Specifically, our area of study is the region of Pavia, located within Mora in the Alentejo region. Portugal’s Alentejo region has one of the highest concentrations of megalithic sites in Europe (Rocha 2022). The megalithic heritage is of great importance for this region and due to the increase in its destruction, recently an opening order of the classification procedure of the megalithic monuments in this area was published, proposing the classification of 2049 monuments, spread over the municipalities (Republic Diary No. 39/2022, Series 2 of 2022-02-25 n.d.) A dolmen is a megalithic structure composed of a chamber, formed by two or more orthostats (upright stone slabs) supporting one or more capstones covering it. It also has a corridor as an entrance, composed of orthostats. These structures may have been covered with earth and stone (burial mounds). In Alentejo (Portugal), this type of monument can have a diameter ranging from 2 to 5 meters, and it is typically constructed using granite or schist (Câmara & Batista 2017; Rocha 1999). The map depicted in Figure 1 shows Portugal with a detailed view of Pavia, highlighting the locations of the dolmens that have been analysed.

5. Methodology

Data Model Implementation

Focusing on the detailed representation of the dolmen’s structural information (object structure), this research emphasizes the monument’s detailed representation and its key identification features (object classes, data source, and designation). The objective was to clarify the monument’s descriptions and to ensure data traceability and integrity. Data about the dolmens was primarily sourced from the (Archaeologist’s Portal n.d.)1 (PA) and by the Carta Arqueológica de Mora2 (CA) (Calado, Rocha & Alvim 2012). These sources provided comprehensive records for a total of 127 dolmens located in Pavia, of which 94 are unique. The next steps involved data analysis, schema definition, mapping and data input in an NGDB. The provided data encompasses information about identification (Class, Designation(s), Period), description/state (Description, Conservation, Classification), access (Localization, Access) and collected remains (Remains, Deposit) for each described monument.

Due to inconsistencies in data descriptions, especially with geographical locations and varied terminology, we standardized geographical information to WGS84 format and extracted it as Well Known Text (WKT). To resolve other inconsistencies, we reviewed each data source that described the dolmens, aiming to extract, standardise, and subsequently convert the relevant information into a more uniform format. Using the source-specific terminology, we defined elements to represent each component, such as material, dimension, and condition state. This standardised information was stored as a semi-structured CSV file (available on GitHub).3 To bridge the language gap and ensure a precise representation of dolmens features and their components in English, we consulted various thesauruses like ROSSIO (Silva et al. 2022; ROSSIO n.d.), GETTY (AAT) (GETTY n.d.), and FISH (FISH n.d). Leveraging these sources and specialised articles (such as (Câmara & Batista 2017), we derived the most appropriate features and English terminology to depict the intricate structure of dolmens, as elaborated in Table 2.

Table 2

Overview of the Representation Framework for Dolmens and their Components. The table delineates the structural categorization of the dolmen, the related vocabulary sources consulted for standardization, and specific attributes characterizing each structure.

| WHAT AND HOW TO REPRESENT: THE OBJECT AND ITS COMPONENTS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OBJECT STRUCTURE | STRUCTURE INFORMATION | ||

| WHOLE | VOCABULARY DATA SOURCE | WHOLE | DATA SOURCE |

| Dolmen | ROSSIO/GETTY (AAT) | Condition State; Material; Dimension; | Features of the object structure that help to recognise dolmens (Câmara & Batista 2017) |

| COMPONENTS | VOCABULARY DATA SOURCE | COMPONENTS | |

| Chamber | FISH; GETTY (AAT) and Bib (Santos et al. 2022) | Shape Condition State Dimension Orthostat – (number and position) capstone (condition state) | |

| Corridor | Bib (Santos et al. 2022) | Condition State Dimension Orthostat (Number and side) | |

| Burial Mound | ROSSIO | Material Condition State Dimension | |

From our analysis of various documents, dolmens are consistently described both holistically and in terms of specific components. At a holistic level, the dolmen is defined by its overall condition, materials, and dimensions. Delving deeper into its components, the chamber stands out, defined by its shape, condition, dimensions, and features such as the number and position of orthostats and the presence of the capstone, whose condition and location are noted. The corridor component also has distinct characteristics, primarily its condition, dimensions, and the number and position of its orthostats. Additionally, if present, burial mounds are described based on their material, condition, and size.

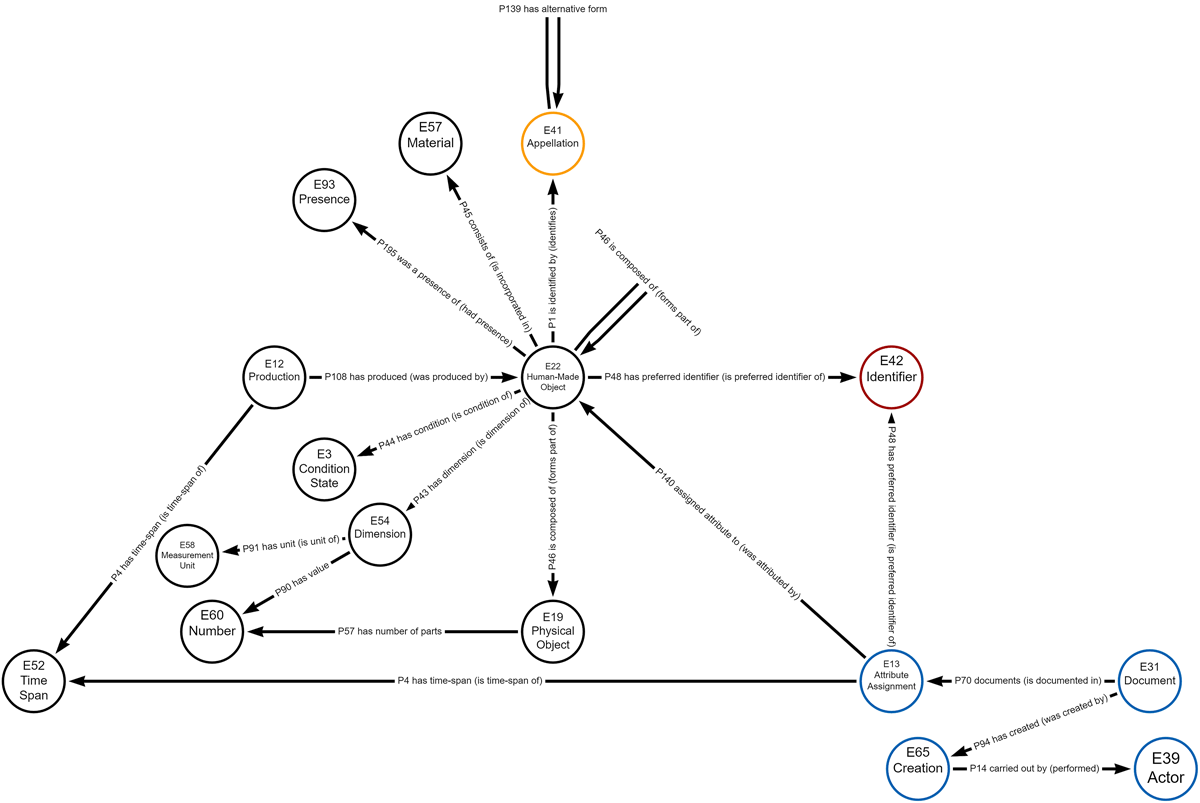

After reviewing how dolmens are described in various documents, it becomes imperative to develop an appropriate and robust data model in order to accurately represent and utilize this wealth of information. CIDOC-CRM achieves interoperability, playing a key role in this process. A set of CIDOC-CRM classes was used as labels on nodes and CIDOC-CRM properties as types of relationships to implement the LPG in Neo4j. A detailed explanation of each class and property from CIDOC-CRM can be found in Bekiari et al. (2021) (Bekiari et al. 2021). Table 3 in Appendix 1 shows the main CRM classes and properties used here and what they represent. The schema model can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Knowledge Graph Schema Illustration. Nodes are labeled with CRM entities, interconnected by CRM properties. Blue circles represent nodes containing data source information, yellow indicates monument designation connected to the dolmen representation node and red highlights nodes with unique identifiers.

To integrate the semi-structured file into the model, we mapped table columns into data properties to populate the KG. Each column in the file served as a label, with subsequent rows containing data in a key-value concept, where the column represents the key and the row’s content represents the value. Every row is distinct, identified by a unique primary key (Global ID), that denotes the monument and its attributes. This structure uses relationships to link the classes. Emphasis was placed on data curation, ensuring entities were accurately linked, matched with corresponding instances, and organized for effective querying and pattern detection. An example of this coding approach can be seen in detail in Query 1.

Query 1: In the provided code, a node E22_Human_Made_Object is created with the property E22Dolmen: ROW. Designation. Next, using the MERGE command, a node E42_Identifier with the property E42GlobalID: ROW. IDGlobal is either checked or established, preventing duplicates. Finally, bidirectional relationships are formed between these nodes, highlighting their identification preference.

CREATE (E22HumanMadeObject:E22_Human_Made_Object {E22Dolmen:ROW.Designation})

MERGE (E42GlobalID:E42_Identifier {E42GlobalID:ROW.IDGlobal})

CREATE (E22HumanMadeObject)-[:P48_has_preferred_identifier]->(E42GlobalID)

CREATE (E22HumanMadeObject)<-[:P48_is_preferred_identifier_of]-(E42GlobalID)

6. Overview of the Approach

Using CIDOC-CRM as the ontological backbone, our KG organizes data with set classes and properties, allowing the ontology and the data to coexist in one graph. The data/instances (stored in the graph database) are separated from the schema/ontology (specified externally). Thus, the same DB can be employed to handle data from different (but compatible) schemas, allowing to limit or expand possible interactions according to specific needs and adding flexibility to the solution.

Our work mainly leans on CIDOC-CRM’s core definitions for monument representation, bypassing its extensions. For instance, the CRMba is an extension tailored to capture topological relationships of functional spaces and is semantically oriented towards representing architectural heritage (Ronzino et al. 2016). However, our approach sought to harness the fundamental elements of CIDOC-CRM as much as possible. For example, particularly when representing the relationship between parts of a single structure, we opted to use the E22 Human-Made Object class and the P46 is composed of (forms part of) property to create a hierarchy of part decomposition. This strategy proved effective for our specific use case.

Every input about a dolmen generates an E22 instance, irrespective of the data source. Each monument is assigned a unique ID, which is represented as an instance in the E42 Identifier class, and which is linked through the P48 property (as shown in Figure 2). As a result, even if a monument has multiple E22 entries, we can determine if they refer to the same object. This approach ensures diverse perspectives and data preservation from multiple record models. While data may evolve, all information accumulated within the ontology remains intact. It’s essential to recognize that details about the object component might be updated due to ongoing research or the passage of time, as elaborated in (Câmara, Almeida, & Oliveira 2023). Utilizing E22 as a class to represent both the dolmen and its components establishes a hierarchical relationship, segmenting components into sub-components. As a result of designing the individual physical structures as distinct elements, the dolmen node is no longer a physical object, but an abstract container that is defined by the association of various types of entities that allow us to describe the monument on a granular level.

The representation of the dolmens’ physical characteristics in a granular way can facilitate their recognition in satellite images. For instance, if a burial mound covers a dolmen, it can obscure the view of its chamber. From this observation, we infer that the chances of visualizing the dolmen chamber are low. As a result, with a granular representation, remote sensing techniques can better target and interpret specific features. For example, while an image might provide a general outline of a burial mound, our detailed model can offer insights into its height, the materials that it is composed of, or its degree of erosion. This level of detail not only enhances the accuracy of dolmen identification and analysis from aerial or satellite imagery but also provides a foundation for automating such processes in the future.

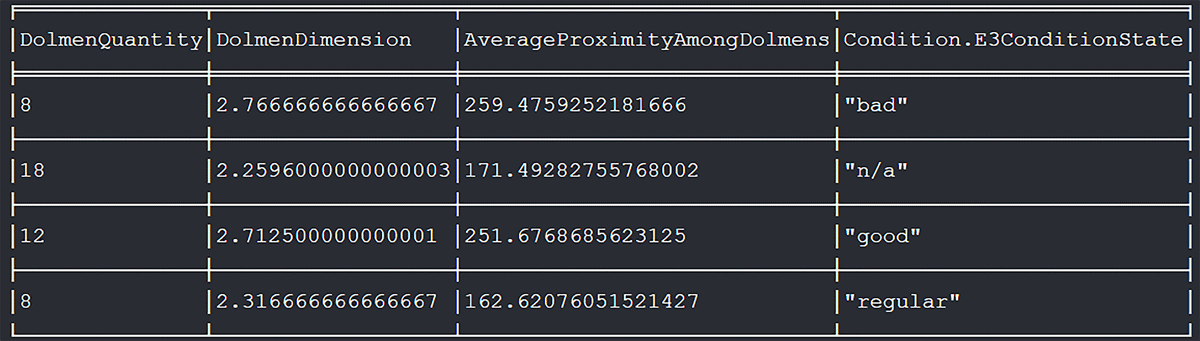

The model covers both quantitative (e.g., measurements) and qualitative (e.g., shape) data about the monument, allowing for granular analysis. Given the data’s diverse nature, it is ideally suited for property-based graphs, enhancing semantic representations of empirical data. This granularity facilitates precise query executions, for instance, swiftly identifying dolmen chambers still remaining, gauging their proximity to similar monuments, and pinpointing details like the average distance between them. As an illustration (Figure 3), in just one query, our model identified dolmens registered as non-‘destroyed’ chambers, those not covered by burial mounds, their proximity to similar registered monuments, and even provided average distances between them. Neo4j facilitates the creation of multi-path queries, enabling simultaneous analysis of various interconnected relations, ensuring rapid response times and offering profound insights into data interconnections.

Figure 3

Analyses of the 73 records from PA in the KG reveals that 46 dolmens were not marked as having their chamber destroyed and were within 1 km of another monument. These dolmens had an average distance of 204 meters to the nearest monument and an average chamber diameter of 2.47 meters. The figure delineates the monuments by conservation status, highlighting average chamber diameters and distances to neighbouring monuments.

Additional layers of interpretation can also be added, such as inferring that monuments described as ‘Destruct’ are no longer visible. Leveraging the inherent strengths of GDB, we can match patterns precisely, providing in many instances millisecond-fast responses (Robinson, Webber & Eifrem 2015). The capability of our KG to discern both direct and indirect relationships, coupled with its depth of contextual understanding, holds significant promise for streamlining data retrieval and interpretation processes.

However, it is crucial to note that not all details about each monument are always available. In fact, in most cases a significant portion of the details might be absent. Taking the condition state as an example, in the Carta Arqueológica de Mora only two out of 53 monuments (3.77%) had the information about the condition state recorded. In contrast, in the data from the PA, 47 out of 73 monuments (64.38%) had this information. The disparity in such information emphasizes the importance of exploring avenues for augmenting it. The incorporation of data from additional sources in the future could potentially fill in these informational gaps and provide a more comprehensive view of the monuments.

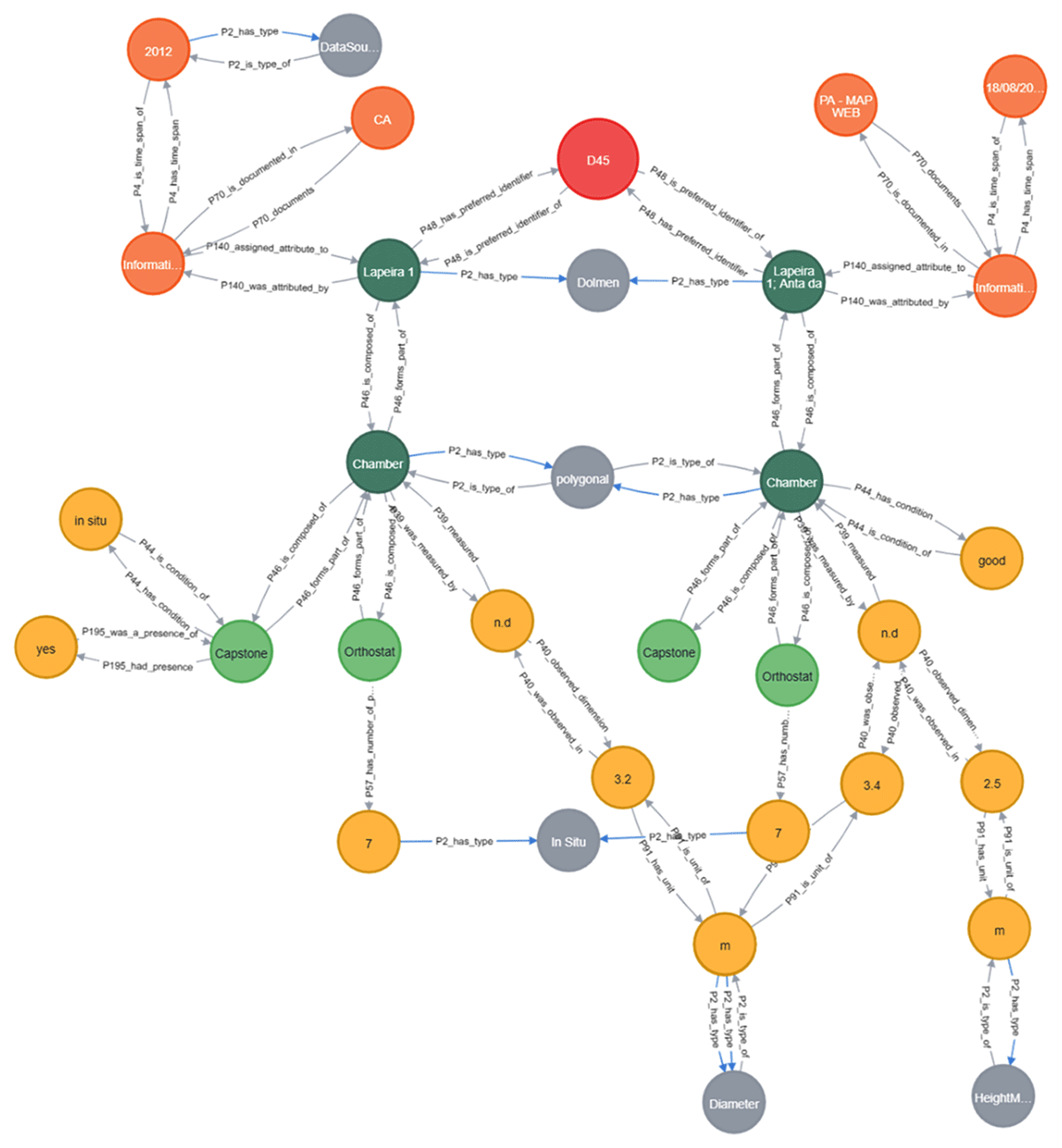

To shed more light on the value of multi-source data integration, we delved deeper into the data surrounding the dolmen Lapeira 1 in our KG, specifically focusing on the chamber’s elements. As depicted in Figure 4, a comparison between the two data sources highlighted the unique pieces of information that each brought to the table. For instance, the PA provided insights about the monument’s height and the chamber’s condition state. On the other hand, the CA enriched our dataset by indicating the in situ position of the capstone. This clear distinction between the two sources underscores the invaluable advantage of harnessing multiple datasets: the ability to offer a more comprehensive and enriched view of the subject. Furthermore, our analysis identified consistent details between the sources, such as the number and position of orthostats and their shape, but also spotted differences in attributes like the diameter.

Figure 4

Here, we can visualise information about the same monument (Lapeira 1) based on two different sources. There are nodes in dark green representing the monument and its components, and light green nodes (E22) representing the objects in the construction (E19). Yellow nodes describe the structure’s information. The orange nodes represent the data sources (E13, E31, E52). A global ID (E42) is represented by a red node. Nodes in grey define components when no specific entity has been identified (E55).

Crucially, the integration of diverse datasets underscores the need for meticulous documentation and the ability to trace back to original sources. Discrepancies can arise when combining information, making it essential to pinpoint each data point to its origin. This ensures both the model’s integrity and provides a clear reference for further validations or challenges.

The fusion of Neo4j’s flexible database capabilities with the structured approach of CIDOC-CRM allows for an interconnected web of knowledge that not only stores information but also interprets it meaningfully. For archaeologists, this is not just a data storage solution, it is a dynamic tool that can reveal patterns in monument construction. As more data gets integrated, its potential grows exponentially. Imagine being able to quickly query the prevalence of certain architectural features across regions or periods, or discerning cultural shifts based on monument positioning and design. This approach bridges the gap between raw data and meaningful interpretation, providing a dynamic tool that evolves with every new piece of information.

7. Conclusion and Future Work

This paper focused on leveraging an LPG implementation using Neo4j to represent domain knowledge about dolmens. A key contribution was the definition of a schema structure to represent these ancient monuments in a granular way using the CIDOC-CRM classes and properties as a foundation to implement a KG into an NGDB. Our current use case offers a comprehensive representation of all architectural components of dolmens. The technology employed, specifically NGDB, allows for robust querying capabilities. These queries can traverse several levels of relationships between data, making the identification of patterns straightforward. More than just a storage system, our model enhances the organisation, storage, management and retrieval of data and sets the foundation for advanced reasoning capabilities.

What distinguishes our approach is its ability to integrate different frames of information originated by different specialists, where the focus is the analysis of the instances represented. This mosaic of empirical data provides a holistic view of each monument as an individual or as a group. The decision to fragment a description into granular parts ensures that only relevant components are utilized in specific queries.

Currently, our data mainly focus on the dolmens themselves. Looking ahead, a primary objective is to expand this by integrating landscape data for scene contextualization and to delve into the spatial relationships between objects related to the dolmen entity. In this way, we aim to gain an understanding of the historical behaviours and rationale behind selecting the location of these monuments. By identifying the patterns of these choices, we aspire to enhance the accuracy of automatic recognition systems.

Data Accessibility Statement

The data and code associated with this research can be accessed at https://zenodo.org/records/10457966.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Table 3

This table describes the main CIDOC-CRM classes used to label KG nodes and their information.

| CLASSES | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| E22 Human-Made Object | This class was used to represent both the dolmen as a whole and its specific components. Discrete used or processed pieces, such as the components from a dolmen, were modelled as parts (chamber, corridor, and burial mound). To relate the dolmen with these components, the P46 is composed of (forms part of) was used, thus creating a hierarchical relation of parts (E22: P46: E22). |

| E19 Physical Object | This class was used to represent the physical objects used to build each component of the Human-Made Object (e.g. orthostats), forming a (E22: P46: E19) relation. |

| E16 Measurement | This class was used to describe, either in terms of the whole, or in terms of each component of the dolmen, the actions taken to measure the object. In order to represent it, the E22 instances corresponding to the dolmen are related to the E16 entity by a P39 measured (was measured by) (E22: P39: E16) relation. |

| E54 Dimension | This class was used to define a value of the element measured. The P40 observed dimension (was observed in) relates the action of measuring an object with the obtained value: (E16: P40: E54). |

| E58 Measurement Unit | This class was used to define a measurement unit of the dimension being indicated, thus the relationship between them is defined by the property P91 has unit (is unit of) (E54: P91: E58). |

| E60 Number | This class was used to identify the number of elements represented as instances of E19, thus the relationship between them is defined by the property P57 has number of parts (E19: P57: E60). |

| E57 Material | This class was used to identify the materials used to build the dolmen components represented as instances of E22, thus the relationship between them is defined by the property P45 consists of (is incorporated in) (E22: P45: E57). |

| E3 Condition State | This class was used to identify the the state of the components represented as instances of E22, thus the relationship between them is defined by the property P44 has condition (is condition of) (E22: P44: E3). |

| E55 Type | This class was used to define concepts and to determine whether it was possible to represent the monuments structure composition only by using the CIDOC-CRM classes and properties. The class E55 was used to define the dimension of the object components (e.g., “diameter” – “height”) (E58: P2: E55), the document of the time span (e.g. “data source date”) (E52: P2: E55), the cardinal directions of the orthostats (e.g “left”, “right”) (E60: P2: E55) and the monument type (“Dolmen”) (E22: P2: E55). In all cases the relation is made thrpugh the property P2 has type (is type of). |

| E42 Identifier | This class was used to attribute an unique ID (Global ID) for each dolmen represented as an instance of E22, thus the relationship between them is defined by the property P48 has preferred identifier (is preferred identifier of) (E22: P48: E42). |

| E13 Attribute Assignment | This class was used to represent action of describing the dolmen’s attributes to the dolmen described – acting as a bridge between the data source and the E22. Thus the relationship between them is defined by the property P140 assigned attribute to (was attributed by) (E13: P140: E22). |

| E31 Document | This class was used to represent the data source from which propositions about the object were gathered (e.g., Archaeologist’s Portal or Carta Arqueológica de Mora) – resulted of describing the dolmen represented as an instance of E13. Thus the relationship between them is defined by the property P70 documents property (is documented in) (E13: P70: E31). |

| E52 Time Spam | This class was used to represent two types of data : i.) A record’s date of origin (data source date) when it has a date, and ii.) the date when the data was acquired and inserted into the KG, thus this class is related to the E13 thought the property P4 has time-span (is a time-span of) (E2: P4: E52). The class E55 Type (previously described) defines date types. |

| E41 Appellation | This class was used to represent the denomination(s) of the dolmen represented as an instance of E22, thus the relationship between them is defined by the property P1 is identified by (identifies) (E22: P1: E41). |

Notes

[1] The “Portal do Arqueólogo” (Archaeological Portal is a platform offering varying access levels for the public, archaeological professionals, and contracting entities to explore, manage, and submit archaeological reports and heritage data in Portugal, managed by the Direção-Geral do Património Cultural (DGPC) and integrated with the “Endovélico” system. Available at https://arqueologia.patrimoniocultural.pt/ [Last accessed 4 March 2024].

[2] The Carta Arqueológica de Mora is a comprehensive documentation of archaeological sites within the municipality of Mora, capturing findings from the Early Neolithic to the Contemporary Period. Initiated as a continuation of previous projects and completed in 2008, it offers detailed insights into the methodologies used and the final outcomes of the fieldwork, entirely financed by the local government.

[3] GitHub: Dolmens Information – Pavia. Available at https://github.com/arielecamara/Pavia_DolmensInformation [Last accessed 4 March 2024].

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the municipality of Mora, Portugal for their collaboration in providing access to the Carta Arqueológica de Mora (Calado, Rocha & Alvim 2012). This resource played a crucial role in enhancing the depth of the implemented Knowledge Graph.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT)/Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior (MCTES) through national funds under Project UIDB/50008/2020 and through ISTAR - Iscte project UIDB/04466/2020 and UIDP/04466/2020 within the scope of the scholarship UI/BD/151495/2021.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Peer Review

This article has been reviewed & recommended by PCI Archaeology (https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.archaeo.100338).