1 Introduction

The human remains trade, conducted over social media and e-commerce websites (as well as via traditional ‘bricks and mortar’ storefronts), has been growing over the last decade (Graham & Huffer 2020; Huffer & Graham 2017, Huffer and Graham 2018), occasionally spilling into public consciousness when sometimes egregious cases come to light (Carney 2007; Patkin 2023; Paúl 2023; Schwartz, 2019). Recent academic research complements efforts by Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) to document and expose how this market operates as a cross-platform phenomenon in order to raise public awareness, and by law enforcement and museums to remove remains from the market and safely curate them until repatriation can occur (Graham, Huffer & Simmons 2022; Halling & Seidemann 2016; Huffer et al. 2022; Seidemann, Stojanowski & Rich 2009).

This paper builds on previous and ongoing research which aims to make sense of this online market ‘at scale’, using data-science and digital humanities approaches to study large corpuses of images, text, and metadata derived from sales posts on public social media and e-commerce platforms. This work has bolstered professional and public interest in the very existence of a market for human remains, and the nuances found within (for a thorough review, see Huffer & Graham 2023). Previous and current research only involves posts that have been made public (or can reasonably be seen as having necessarily waived expectations of privacy). In so doing, previous research has identified certain patterns of discourse and rhetoric that often seem clearly intended to circumvent legislative or regulatory conditions that may exist. Some of these rhetorical devices are global in use, while some are more confined to major markets such as the United States.

From time to time, human remains are seized in transit by customs agents or law enforcement and removed from circulation. When remains can be physically studied in such contexts, investigations now often involve methods from osteology, forensic anthropology, forensic taphonomy, DNA analysis and potentially stable and radiogenic isotope analysis (Gill, Rainwater, & Adams 2009; Houlton & Wilkinson 2016; Huffer, Guerreiro, & Graham 2021; Watkins et al. 2017; Winburn, Schoff, & Warren 2016). Research into the online component of the human remains trade (and indeed any grey or black-market trade) can provide context and ‘intel’ to support case-specific physical evidence that can come to light when law enforcement has the opportunity to investigate shipments seized in transit. Crucial to these efforts is understanding the full scope of the market everywhere it exists.

Country and region-specific variation exists in numerous illicit/illegal trades. To understand any global trade holistically, one needs to understand the intricacies of individual nations or regions, and how these intersect with other regions. That is to say, the global trade emerges from these regional/country/state dynamics and in turn influences them. To date, research has focussed on the North American and European contexts of the human remains trade, but new research continues to demonstrate that Australia remains important as both a source and destination country within many illicit or illegal markets, and that Australian collectors and dealers not only circulate items internally but have access to and interest in international markets (e.g., Bright et al. 2023; Chappell & Huffer 2013; Hughes, Bright & Chalmers 2017; Lassaline et al. 2023; Morgenthaler & Leclerc 2023; Tiwari & Ferrill 2023).

To add to this growing body of work, this paper reviews and contextualises a unique ‘sales tactic’ that seems to be confined to the Australian human remains trade, to the best of the author’s current knowledge. The tactic permits human remains to circulate within the networked Australian and international collecting community and allows traders to generally circumvent current cultural property and human remains legislation. It can be summarised as the offering of human remains as a ‘gift’ to accompany the purchase of a photograph; sometimes the photograph is of the remains themselves, sometimes it is something entirely unrelated. Specific research questions include: What categories of human remains are exchanged using this technique? How is real money exchanged in name for virtual images of authentic remains? And what does the use of this technique accomplish or create within the larger rhetorical landscape of the Australian human remains collecting community?

2 Background

2.1 Unboxing the ‘gift’

The very idea that human remains could be seen as ‘collectible’ is often alarming to most people when they first encounter it online, whether deliberately or accidentally. Although the human remains trade could be considered a ‘niche’ within the much more wide-spread antiquities trade, ‘everyday’ encounters with the antiquities trade rarely include bone. The major online platforms for social media and e-commerce often include in their terms of service language that would seem to prohibit trading in antiquities or human remains (Mashberg 2020; Meta 2020). Therefore, buyers and sellers must be innovative to avoid platform algorithmic detection or occasional human moderation to exploit known or suspected legal loopholes. Here I examine one such dynamic as it appears in the Australian context: the use of words to the effect of ‘buy the photo and get the bones as a gift’. It is a sales tactic known and reported on for at least ten years (Begley 2019; Rachwani 2021; Webb 2013), but the rise of social media has made its use commonplace. The text of two example posts is paraphrased below:

Post 1: ‘Would someone gift (wink emoji) … a man/woman femur or two?’

Post 2: ‘Oddlings! I have something … special available. … You will receive the photo plus a free vintage medical specimen … real (bone emoji). (Ship emoji) inc. payment plans available.’

To understand how and why this rhetorical tactic came to be, and how it is used by collecting networks within Australia, the below is a paraphrasing of one collector’s explanation of the significance of this type of ‘gifting’ (capitalisation reflecting the emphasis of the original poster):

‘In Australia, it is LEGAL to have human remains in your possession, wet specimen or osteological, for educational purposes AND PERSONAL CURIOS. It is ILLEGAL to buy or sell human remains of any sort within the country, but they can be GIFTED. … If you don’t like the thought of another person’s remains in your collection, don’t get human specimens. Other people will collect what they wish, as they wish.’

On current best evidence, the use of this ‘loophole’ (called as such by several collectors) appears common, especially when commerce occurs within Australia, but perhaps across State or Territory lines. In datasets from earlier studies (composing materials ranging in date from 2013 to 2017 in the first instance (Huffer & Graham 2017), and roughly from 2019 to 2020 in the second (Graham and Huffer 2020) no posts surfaced that could be confidently said to be from Australia. It might be a function of some kind of geolocation happening in the background on Instagram – data collection was run from Ontario, Canada). The ubiquitousness of the rhetorical phrase as observed and used for at least the last two years within the Australian online collecting community makes it worth interrogating in light of current legislation.

2.2 What does current legislation say?

This section provides a summary review of the relevant Australian legislation surrounding the import, export and sale of Australian First Nations and non-Indigenous cultural heritage and human remains, as well as general Australian e-commerce and false advertising legislation. Overviewing both areas is needed to demonstrate what specific legislative constraints the use of this sales tactic is trying to circumvent.

The import, export, and sale of cultural property, Indigenous or otherwise, is primarily legislated by the Protection of Moveable Cultural Heritage Act (PMCHA) 1986 (for a thorough review, see Forrest 2004). It primarily applies to situations of illicit export from or import into Australia, but not restitution due to theft initially occurring within the country of origin. Any item exported in contravention of source country cultural property retention legislation and subsequently imported into Australia would be forfeited, and penalty units and fines accrued. All categories of human remains that are also considered cultural heritage by descendent communities or cultural property by the country of origin would be barred from import without appropriate permits.

A thorough review completed in 2015 indicated several areas requiring update, especially regarding clearer definitions, distinguishing Ancestral remains from trafficking of material culture in general, better synergy between the PMCHA 1986, Australian State-level and international legislation, and a smoother process for foreign States to affect returns (Australian Government n.d. a). This legislation, while crucial to repatriation efforts where public and private institutions and private collectors or dealers are found to have broken the law, has only been used in cases involving human remains four times to date (Australian Government n.d. b). Other legislation exists that attempts to govern the acquisition and inter-state transport of human remains instead.

Aside from the PMCHA 1986, intended to manage Federal level import and export of any cultural property including human remains, each State or Territory has a version or versions of Human Tissue Acts, Transplantation and Anatomy Acts or Cemetery and Crematoria Acts to govern how crematoriums, mortuaries, body donation programs and funeral homes operate, how tissue transplants occur, and how contemporary non-Indigenous remains should be dealt with (e.g. Queensland Transplantation and Anatomy Act 1979; New South Wales Cemetery and Crematoria Act 2013; Philpot & Anderson 2021). In addition, the Federal level Biosecurity Act 2015 further dictates the conditions under which already-cremated ashes, decedents intended for burial or cremation in Australia, dry remains intended to be used for alleged ‘teaching, scientific or research purposes’, and all remains to be used for ‘other purposes’ (including for display or as curios) could be imported into or exported from Australia.

The only substantial requirements under this Act are that any hair, teeth, or bones for import must be clean, that import of human remains for purposes not related to immediate burial or cremation or valid scientific or research purposes should hinge on permission being granted by a biosecurity officer before shipment to Australia or at place of first arrival, and that the remains are inspected and seen to be free of any evidence of disease as per a narrow range of listed pathogens that might pose risks to Australian health. And yet, as will be discussed below, this does not stop remains sold in a variety of conditions from entering, leaving, or crossing state borders.

Australian law is more complicated, and generally silent, when it comes to the specific phenomenon of selling or arranging bidding on a photograph of an item and then providing the item in question as a ‘free’ gift, whether the item ‘gifted’ is actually depicted in the photograph purchased or not. The Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (ACCC) notes on their website that Australian consumer law applies to social media promotions or advertising made by businesses in the same manner as advertising on other media, holding that businesses should not make false or misleading claims (ACCC n.d.). However, human remains in Australia, as well as globally, are primarily bought and sold by individuals who do not run any associated online or ‘bricks-and-mortar’ businesses that might seek to advertise on social media. Similar tactics, however, have been used by individual dealers or business owners in other contexts, such as certain unlicenced cannabis dispensaries in the United States selling paid memberships to clubs where one can then get “free” marijuana (Southall & Regan 2023).

In a paper on why people buy illicit goods, Albers-Miller (1999) outlines four predictor measures that influence the cost-benefit analyses performed when one is considering whether to purchase potential or known illicit goods: price, product type, buying situation and perceived criminal risk. The selling price, situation under which the purchase occurs, and the associated risk all factor into decision making, but in this study, participants (a cohort of employed Masters in Business Administration students from a university in the southwestern United States) were asked to consider hypothetical purchases of goods known to be counterfeit or illegally obtained. Peer pressure increased respondent’s tendency towards making illicit purchases, much as price increased the perception of authenticity in scenarios where counterfeit goods were offered. Such considerations can also apply to born-digital artifacts as well. Recent criminal law research investigating how ‘non-fungible tokens’ or NFTs are used, marketed, and sold is highlighting how the purchase of NFTs can conceal other forms of fraud and theft. Hufnagel & King (2023) note that if a person were for example to purchase an NFT to conceal criminal property, or to convert such property to a different medium, they would have committed an offence under section 327 of the (UK’s) Proceeds of Crime Act 2002. While this is not an exact analogy, it is arguably similar. In this paper, I delve deeper into how real money is exchanged in name for virtual images of authentic remains.

3 Methodology and Research Ethics

3.1 Ethical considerations

As is the case in research investigating a wide range of illicit trafficking, alt-right communities, Child Sexual Assault Material (CSAM) production and online trading, and the like, it is generally accepted that a researcher exposing their identity or attempting transparent contact would threaten the ability to conduct real-time research, and possibly risk the researcher’s security or safety if doxed, resulting in their personal identifying information being publicly released (e.g., Calvey 2008). In previous articles, colleagues and I have also publicly described our approach to conducting online human remains trade research ethically, and in a way useful to both academics and law enforcement, especially given the ‘duty to report’ civilian researchers arguably face when especially egregious examples are encountered online (Graham & Huffer 2020; Huffer, Wood & Graham 2019).

Richardson (2018) suggests that anyone engaged in studying illicit or illegal behaviour or activity online also has an ethical duty to consider the privacy of individuals, whether the data is obtained through manual screen-capture or via automated trawling. To respect the privacy of the individuals active in these posts, the author anonymised any posts discussed below, removed all identifying information before saving and storing each screen capture and analysing the complete dataset, and paraphrased comments to illustrate broader patterns.

3.2 Methodology

To date, seven Facebook groups, containing sales posts and individuals providing links or information about their or other’s personal and business pages have been identified as spaces within which human remains buyers and sellers in Australia advertise their wares, reaching both domestic and foreign clients. Most of the search categories through which human remains are advertised to Australian consumers fall within the broader realm of ‘oddities’ (taxidermy, animal bones, items from medical history, and a variety of items deemed ‘macabre’ or ‘bizarre’). Long-term periodic monitoring of these Australia-centric ‘oddities’ groups was conducted using a so-called ‘lurker’ account, allowing for non-participant observation.

In this approach, research-specific profiles are used to observe activity and the observer takes screen-captures of relevant posts while excluding personally identifiable information. Collecting data by these means is a common approach to studying online communities, especially where the possibility of illicit or criminal activity exists (e.g., Markham 2013; Pollock 2009; Williams 2023). Sales posts and all associated comments and metadata visible when each post was first encountered were screen captured from each post. The particular ‘oddities’ groups from which the sample set derives have been monitored for approximately two years to date. The sampled posts themselves span the period 4 March 2021, to 16 June 2023. They represent a diverse sample suitable for an initial analysis of the function of this specific rhetorical device.

Posts relevant to this research were collected by Huffer within Australia, and were discovered using keyword searches on public social media devoted to ‘oddities’ collecting within Australia, such as #oddities, #humanskullforsale, #humanskull, #humanbone, #mementomori, etc., and from there, by means of covert ethnography within select Facebook groups using a purpose-built ‘lurker’ account that doesn’t interact with other users but exists merely to provide an observation post. ‘Covert’ ethnography, whether digital or otherwise, is generally defined as research in which the researcher deliberately decides to not declare their identity as a researcher to subjects, nor that the research is occurring (Bryman 2012: 433–436). It is a relatively new approach, especially where work occurs in online communities and where the community under observation might be united by sensitive or potentially criminal topics (Cera 2023; Masullo & Coppola 2023). The dataset compiled here was not assembled by means of automated ‘scraping’ or web crawling. Instead, each relevant post (among a majority within each group not related to human remains) was manually screen captured when observed, specifically due to its visual or textual content.

Using the methodology described above, 33 posts were selected according to specific search criteria and observations made. Criteria for capturing a post included a) clear mention and use of some version of the ‘buy the photo get the bones as a gift’ phrasing, and/or b) clear queries about what would be purchased in the comments (a photo or the remains themselves), and/or c) questions about or discussion of issues of legality or shipping to or from Australia, and/or d) posts indicating that international sales were possible. All text within each post and all comments was transcribed verbatim into a spreadsheet, together with qualitative data recording the date of capture, date of initial posting, the total number of emoji responses (likes, hearts, etc.) at the time of capture, and the total number of comments at the time of capture. The language shared here is not necessarily indicative of every possible permutation or use of the specific phrase in question. As is discussed further below, the specific rhetoric used in the sales tactic under analysis makes it clear that the intent of the posts is still to exchange money for human remains.

The research presented here and discussed below takes a constructivist grounded theory approach. Grounded theory, in principle, explores the ‘how’, ‘what’, and ‘why’ of social phenomena, seeking to understand how participants interpret reality related to specific situations or processes under examination. Data collection and analysis is iterative and often opportunistic or via a ‘snapshot’ approach, and the data collected can take many forms, on or off-line. It is a structured, yet flexible, methodology especially suitable when little is known about the phenomenon or community being researched (Eppich, Olmos-Vega & Watling 2019; Tie, Birks & Francis 2019). Grounded theory is frequently used within social science to inductively generate concepts from rich, qualitative data and where data and analysis are concurrent, and this approach is especially useful for the very large volumes of data obtainable in social media research (Brunson & D’Souza 2021). It is a methodological approach frequently employed in sociology and criminology where online communities, and online criminal activity, are the topic of study, as it allows connections between topics to emerge within digital spaces that are inherently nebulous (e.g., Jian et al. 2020; Lee & Jang 2023). Taking this approach, the author iterated through the 33 posts and their responses several times (which gave 279 ‘speech acts’, as it were, within those 33 ‘conversations’) to identify 11 themes and the number of conversations focused on the given theme (see Table 1).

Table 1

Identified themes and the number of commentor-to-commentor conversations around each theme within the corpus.

| THEME | CONVERSATIONS WITH THAT THEME |

|---|---|

| PicsForSale | 17 |

| ItemIsAGift | 13 |

| BasicQuery | 12 |

| PricesGiven | 9 |

| PMforDetails | 9 |

| SourceOfBones | 8 |

| CrossPost/Repost | 8 |

| PostageCoversPriceofGift | 6 |

| IsThisLegal | 5 |

| Ethics(Ours) | 4 |

| StorySellsThePhoto | 3 |

Network analyses were performed using t-distributed Stochastic Neighbour Embedding (t-SNE), a standard dimensionality reduction technique (van der Maaten & Hinton 2008), as well as Voyant Tools, an open-source, web-based text analysis platform. These tools in combination are especially suited to large corpuses of digital text such as social media posts (Sampsel 2018).

4. Discussion: Discourses of the Gift

Table 2 provides definitions of some of the less self-explanatory themes that emerged from network analyses of the dataset, and anonymised, paraphrased, excerpts of post text illustrating each theme. Given the premise of the research and the search criteria used, the obvious theme explaining the nature of the ‘loophole’ these collectors and dealers exploit dominated the discourse. That is, the clear ‘the picture is for sale, while the item depicted is a free gift!’ rhetoric. Despite their reliance on this ‘loophole’, comparatively few posts will state a price openly, which suggests a certain hesitation about whether or not the loophole actually would stand up to legal scrutiny. The number of ‘PMforDetails’ indications is similar to what colleagues and I have seen elsewhere in the trade (for a summary overview, see Huffer & Graham 2023), where the initial contact is made through the open platform and the details of cost are hashed out beyond prying eyes. This suggests perhaps a bit of hesitation around the ‘strength’ of the BOGO (“buy one get one”) premise, where the photograph is purchased but the bones gifted. The ‘PMforDetails’ theme does not perfectly overlap with the ‘ItemIsAGift’ statement. Indeed, the ‘PicsForSale’ and ‘ItemIsAGift’ phrasing are almost an invocation, a get-out-of-jail free card, again suggesting nervousness. Further support of the argument that the creation and use of this rhetorical devise arose out of uncertainty among both buyers and sellers is the existence of the ‘Ethics(Ours)’ theme. The ‘basic queries’ are generally of a how-do-we-do-this nature, which is seen frequently within the wider trade.

Table 2

Select identified themes or concepts, their definition, and example text.

| THEME | GENERAL DEFINITION OF SELECT THEMES | EXAMPLE PARAPHRASED TEXT |

|---|---|---|

| The BOGO gambit | Wording to suggest that the remains are being gifted instead of sold. | “For sale is the photo, item is a gift that comes with it.” |

| SourceOfBones | Inquiring as to the source of the remains. | “Where can one source a human skull from in Australia…without sounding like a psycho…?” |

| IsThisLegal | Discussion of the legality of what buyers or sellers are doing or proposing to do. | “What are the rules applying to human body parts? Is a licence needed?” |

| Ethics(Ours) | Discussion of the ethical stance of those who buy, sell, or ‘gift’ remains. | “I revel in telling people who try to judge or shame me for my collecting. Make them as uncomfortable as possible… Keep collecting. Don’t ever hide what makes you happy.” |

| QualitySeller | Discourses signalling or querying the quality of the ‘goods’ that the seller provides, where ‘quality’ can be understood as both the material and story/source | “Couldn’t recommend the seller enough, fast, well priced and professional.” |

| Persecution Complex | Displeasure at how the human remains collecting community is viewed. | “What have I learnt today. Don’t tell anyone I talk to apart from on these groups of course that I was gifted hooman bones and dog skulls. Oh boy did I get a lecture today about how illegal and immoral it is with the human bones…” |

A broader theme also occurs within the observed conversations beyond the 11 themes listed in Table 1 identified via network analysis. This overarching theme could be summed up as ‘Persecution Complex’ and is characterized largely by a difference in tone: one user will vent their frustration at how their wider social circle/the wider world looks askance at their ‘hobby’. The resulting conversation is a chorus of support. Such conversations are helpful for the light they shed on the self-representation of traders and the way they justify this trade. If the trader is persecuted, then the trade becomes a heroic endeavour. If the trade is a heroic endeavour, then traders are on the side of right, which means that it is justified to be buying and selling human remains.

These persecution complex conversations, seen both here and in datasets from previous research on Instagram and elsewhere (Huffer & Graham 2017; Graham & Huffer 2020; Huffer & Graham 2023), often intersect with the ‘IsThisLegal’ discourse, and the ‘BasicQuery’ discourse. As Dundler (2021) has shown, antiquities dealers adopt one or more of four general ‘dealer personas’ in other domains. These can be defined as the performance of a) trust and discretion (authenticity guarantees and collecting advice), b) professional expertise (showing off of credentials or past alleged collaborations with academics or laboratories), c) legitimate relationships with the ancient world (and/or the dead), and d) professional ethics (stated awareness of relevant legal concerns). In this way, individuals who start these conversations in the ‘Persecution Complex’ discourse signal authority within the community—a combination of personas a and d, often mixed with c.

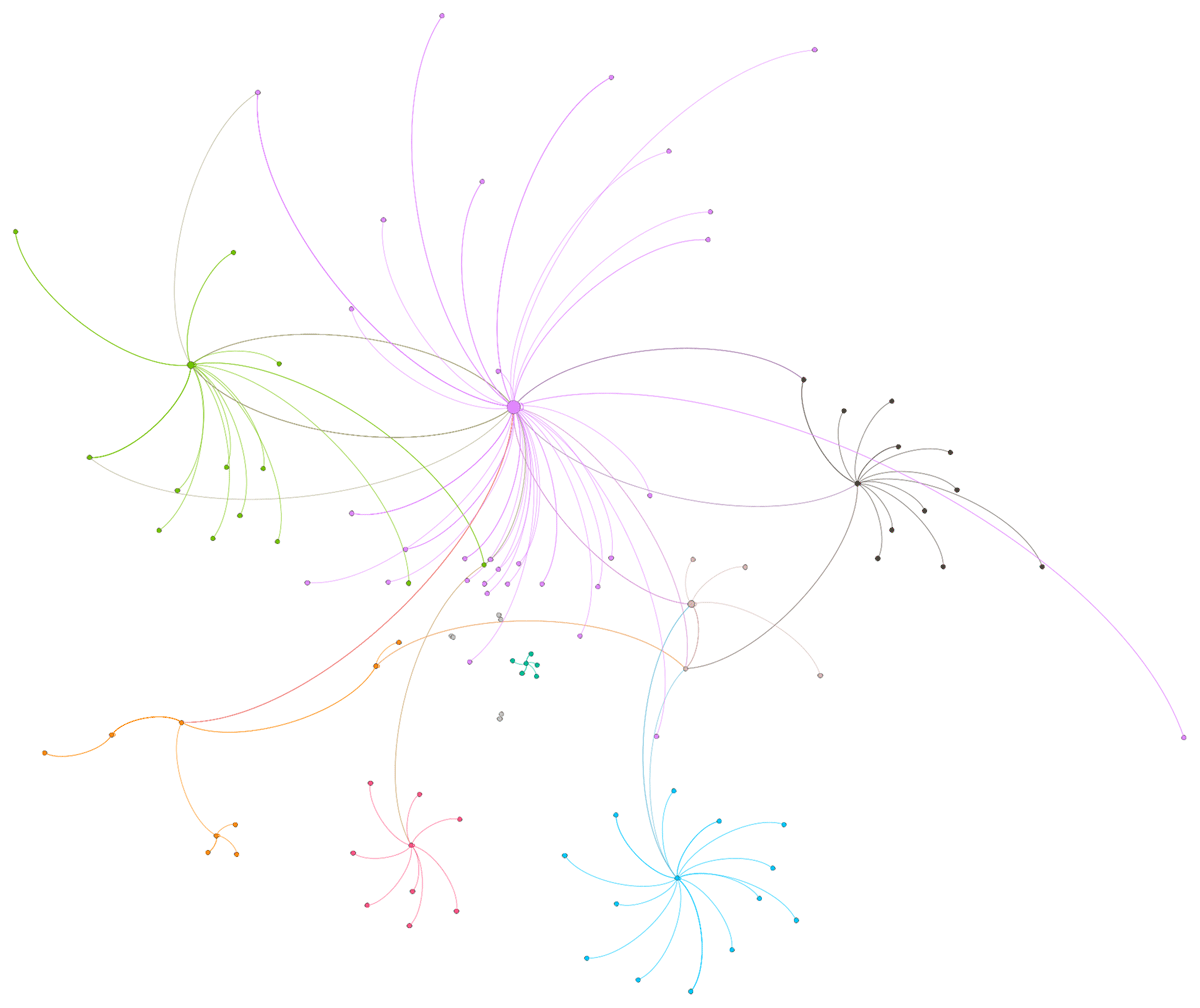

If a network visualization of the conversations is created, numerous pinwheel-shaped interactions are revealed. That is, the original poster will make a post, and a handful of individuals will respond to the post, but there will be few secondary interactions where the original poster responds to individuals. In Figure 1, the network is visualized using Voyant Tools to show posts by key players (the central node in each pinwheel) and responses to each post (the arms). The dataset at hand suggests that there are three individuals within it who occupy the most ‘between’ positions and who are pushing the use of this sales tactic and, unlike a lot of the participants, they also respond to other peoples’ posts. This is in keeping with patterns previously found in public buying and selling networks on platforms such as Instagram, where it’s mostly a small group of high-profile individuals who control everything (Huffer & Graham 2017; Graham & Huffer 2020).

Figure 1

A network visualization created using Voyant Tools showing posts by key players (the central node in each pinwheel) and responses to each post (the arms). Copyright c/o the author.

The network visualized here represents 278 separate exchanges, and not all exchanges are reciprocal. In other words, person A posts, B responds, C responds, D responds, but A seldom responds to them.

The colour indicates subgroups (based on the graph-theoretic pattern of interactions; formally, these are ‘modules’ of connections that are more similar to each other than they are to other interactions) while the size of the node indicates the ‘betweenness centrality’ of an individual—in this case, the degree to which they facilitate conversations or knowledge flow across the different conversations. These individuals with high betweenness centrality in the network obtainable from the data at hand also, as it happens, are involved in conversations where others praise them for the quality of their trades or the quality of personal interactions in private messages they’ve experienced (this is the ‘QualitySeller’ discourse). Thus, they function as role models, promoting the ‘buy the picture get the item as a gift’ gambit.

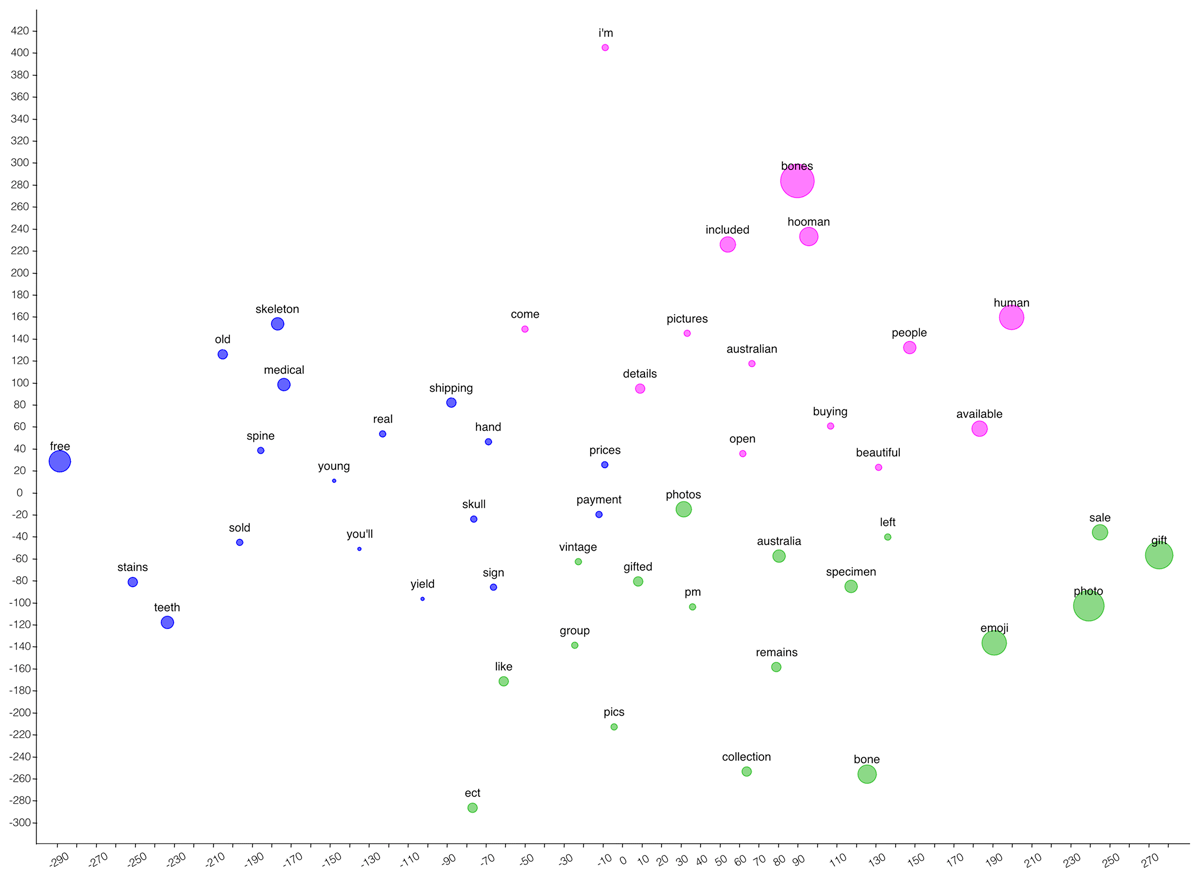

Figure 2 is a t-SNE plot of the top 50 words in the corpus expressed as relative frequencies and coloured into three main clusters, also created using Voyant Tools. It is clear how use of the term ‘gift’ plays out in these posts frequently co-occuring with ‘photo’, ‘sale’ and ‘emoji’. The different clusters can be thought of as three different prominent discourses.

Figure 2

A t-SNE plot of the top 50 words in the corpus expressed as relative frequencies and coloured into three main clusters (pink, blue and green circles), created using Voyant Tools. Copyright c/o the author.

Comments on posts within the examples examined for this paper also make it clear that not only cleaned and bleached ‘medical skeletons’ are sold this way, but also cremains, wet specimens (such as organ slices), and even archaeological or ethnographic Ancestral remains allegedly imported from abroad. This rhetorical device has become something of a catch-all phrase within Australian collecting circles (similar to use of the phrase “no no states”, used when collectors based in the United States or shipping to the United States want to refer to perceived blanket legal restrictions on import into or sale and purchase within Louisiana, Georgia, and Tennessee) (Breda 2023).

5 Conclusion

This research is intended as a first step towards further comparative analysis of how specific rhetorical devises, codewords or symbolism operates within the online human remains trade in Australia and internationally, complimenting other recent work (e.g. Breda 2023). Such investigations can be accomplished using a variety of qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods approaches, including network analysis. While still relatively rare for human remains or antiquities trafficking, investigation of the use of emojis, code words, rhetorical devices, and the like within other trafficking communities is becoming more routine (Balasuriya et al. 2016; Breda 2023; Parise 2020; Polisar et al. 2023). In this case, identifying and sketching out the phenomenon is the first necessary step towards searching across platforms for the use of this rhetorical device and conducting larger social network analyses from larger datasets.

This paper, taking a snapshot of a particular sales tactic seemingly unique to the online human remains collecting community in Australia, has demonstrated that ‘buy the photo and get the bones as a gift’ remains in relatively frequent use as a means to circumvent legislation and avoid triggering algorithmic detection or any consequences in case a post is reported. It is readily used within each of the seven groups from which examples were sourced for this study. It is a means to sell and move remains interstate (including both alleged ‘medical specimens’ with their own ethically and morally complex history, as well as alleged ethnographic or archaeological human remains imported at some point previously, possibly before current legislation).

In a broader sense, the use of this sales tactic within the Australian collecting community makes it similar to (and connected to) larger international networks, where only a handful of individuals are mostly responsible for knitting online communities together. It is therefore these individuals whose words and images tend to set the pattern for how others interact. In essence, these individuals teach others how to be active in this trade. By documenting and beginning to assess the use of this specific rhetorical device, this paper also demonstrates that the Australian human remains collecting community does not suffer ‘isolation by distance’ but has instead created a purpose-built means to participate in global networks and circulate material internally. More investigation is needed to document if/how this technique is used on other platforms, the time depth of its observable use, and how its use might change over a longer period of time, but the work presented here is a first step towards the legislative reform needed to close this loophole.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their useful feedback on this manuscript, as well as the editors of this special issue for the invitation, and Prof. Shawn Graham and Ms. Katherine Davidson (Carleton University, Department of History) for their informal advice.

Reproducibility

All raw data and original anonymised screen captures are stored securely in external hard drives in the author’s sole possession, but accessible via direct request by email.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.