Chronic liver disease represents a global health concern with increasing worldwide prevalence. End‑stage fibrosis, or cirrhosis, most often results from repeated injury related to excess alcohol intake, chronic infection with hepatitis C or B virus, and/or metabolic‑dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). A wide variety of less common etiologies include various autoimmune and inherited conditions, including hereditary hemochromatosis related to iron overload. Beyond liver‑specific complications, MASLD also carries important cardiovascular health risks associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome.

Definitive detection and quantification of diffuse liver involvement by fat, iron, and fibrosis may ultimately require liver biopsy. However, this approach has a number of major disadvantages, including cost, complications, and sampling error related to the invasive technique. More recently, quantification of fat, iron, and fibrosis using MR imaging techniques has emerged as the noninvasive reference standard. In particular, MR‑based proton density fat fraction (PDFF), R2* mapping, and elastography are now widely considered to be the preferred measures for routine noninvasive quantification of hepatic fat, iron, and fibrosis, respectively, in routine clinical practice (Figures 1 and 2).

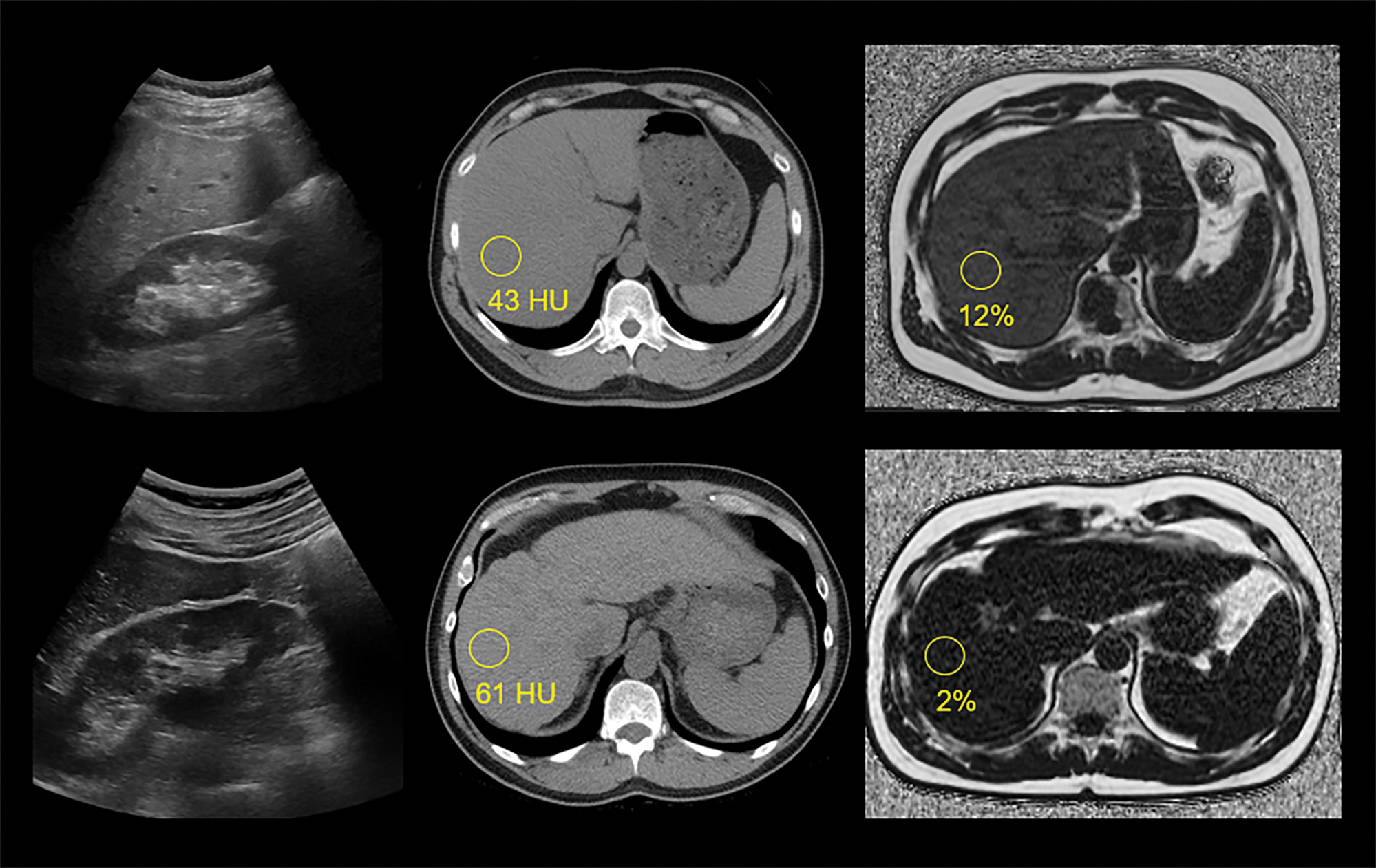

Figure 1

Examples of steatotic and fibrotic livers at US, non‑contrast CT, and MR‑PDFF.

Source: Figure 1 is from Pickhardt PJ, Lubner MG. Noninvasive quantitative CT for diffuse liver diseases: steatosis, iron overload, & fibrosis. RadioGraphics 2025;45(1):e240176 with permission (authors retain the right from RSNA for reuse of images).

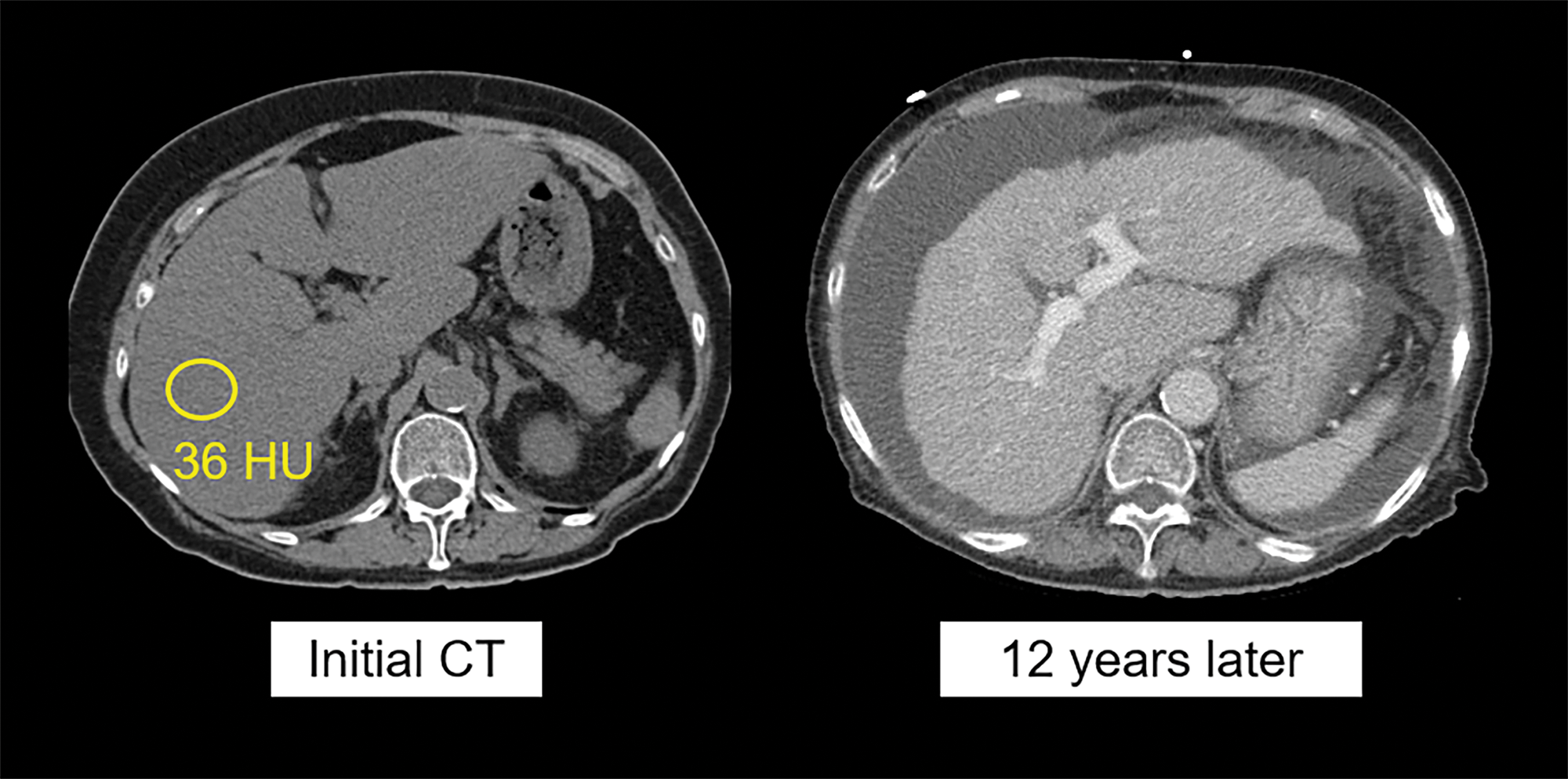

Figure 2

Progression of liver‑specific disease in metabolic‑dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD).

Source: Figure 2 is from Pickhardt PJ, Lubner MG. Noninvasive quantitative CT for diffuse liver diseases: steatosis, iron overload, & fibrosis. RadioGraphics 2025;45(1):e240176 with permission (authors retain the right from RSNA for reuse of images).

Compared with MR imaging, the ability of abdominal CT to both detect and quantify fat, iron, and fibrosis has received considerably less attention. Due in part to the lack of ionizing radiation, MR (and presumably ultrasound (US) in the future) will likely represent the preferred methodology for intended noninvasive liver quantification. However, abdominal CT imaging volumes are substantially higher than abdominal MR, and its potential role for opportunistic detection (and quantification) of diffuse liver diseases should not be overlooked. Furthermore, quantitative CT assessment can be performed retrospectively, as it generally does not rely on prospective planning for specific protocol sequences or maneuvers like MR‑based PDFF, R2* mapping, and elastography. CT assessments for hepatic fat and fibrosis are generally more accurate than the standard subjective US techniques currently in clinical use, although emerging objective US algorithms may help narrow this gap. In addition, the various manual measurements utilized for CT‑based quantification have all been automated with AI deep learning algorithms and should become more clinically available in the near future. These retrospective and automated aspects have important implications for both longitudinal clinical care and research.

This talk will discuss the full spectrum of MASLD (Figures 1 and 2), from hepatic steatosis to MASH, fibrosis, and cirrhosis (and HCC), as well as the broader issue of metabolic syndrome and its cardiovascular implications. The potential role for CT as a value‑added opportunistic means for the often unintended detection of abnormal hepatic fat and fibrosis will be emphasized, which can then feed into dedicated MR (or US) surveillance programs, as clinically indicated.

Top row images are from a 44‑year‑old man with mild‑moderate hepatic steatosis, including a conventional US image (left) showing subjectively increased parenchymal echogenicity, particularly compared to adjacent renal parenchyma, a non‑contrast CT image (middle) with liver measuring 43 HU, and an MR‑PDFF map (right) showing 12% fat fraction.

Bottom row images are from a 58‑year‑old man with chronic liver disease and advanced fibrosis but without steatosis, including a conventional US image (left) showing normal parenchymal echogenicity, a non‑contrast CT image (middle) with liver measuring 61 HU, and an MR‑PDFF map (right) showing 2% fat fraction. Note CT and MR findings of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis, including nodular liver contour and segmental redistribution.

Non‑contrast CT image (left) in a 76‑year‑old woman shows moderate hepatic steatosis (36 HU, corresponding to 17% MR‑PDFF), as well as some degree of segmental redistribution and fissural widening, indicating likely fibrosis. Contrast‑enhanced CT (right) performed 12 years later demonstrates advanced cirrhosis and portal hypertension with obvious surface nodularity and ascites. The patient died of end‑stage liver disease within a year of the latter scan.

Competing Interests

Advisor to Bracco, Nanox‑AI, GE HealthCare, and ColoWatch.