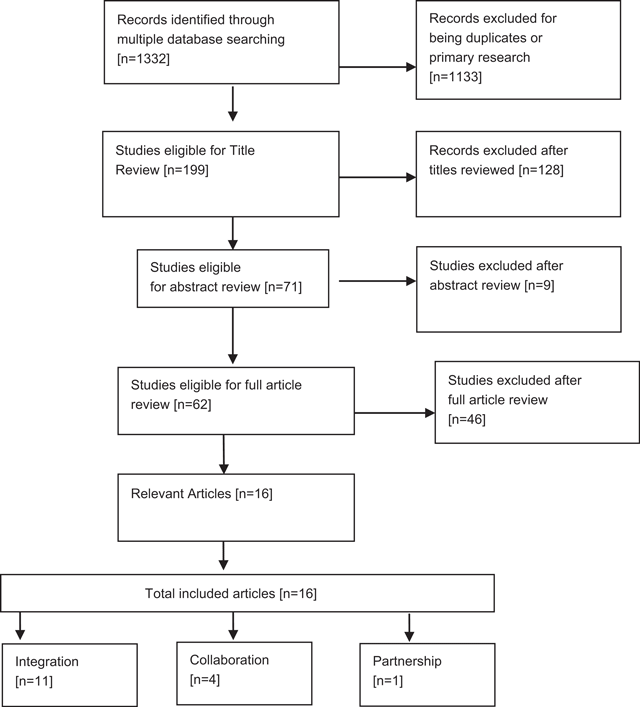

Figure 1

Study selection and exclusion flow diagram.

Table 1

Search terms.

| health OR social care, AND partnership, OR collaboration, OR integration, OR joint working, OR coalition, OR alliance, OR interprofessional, AND cross sector, OR bridging, OR multisite, OR inter-sectorial, OR across, AND service provision OR delivery |

Table 2

Quality appraisal checklist scores.

| Author | Score | Reject or retain |

|---|---|---|

| Butler (2011) | 10/11 | Retain |

| Collet (2010) | 10/11 | Retain |

| Davies (2011) | 10/11 | Retain |

| Donald (2005) | 8/11 | Retain |

| Dowling (2004) | 5/11 | Retain |

| Fisher (2012) | 7/11 | Retain |

| Fleury (2006) | 6/11 | Retain |

| Green (2014) | 11/11 | Retain |

| Grenfell (2013) | 8/11 | Retain |

| Hillier (2010) | 8/11 | Retain |

| Howarth (2006) | 9/11 | Retain |

| Hussain (2014) | 10/11 | Retain |

| Lee (2013) | 6/11 | Retain |

| Loader (2008) | 1/11 | Retain |

| Soto (2004) | 5/11 | Retain |

| Winters (2015) | 8/11 | Retain |

Table 3

Characteristics of included studies of cross-sector service provision.

| Author | Title | Consumer group | Sectors | Intervention | Primary term | Year range of included studies | Location of authors | Included articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butler (2011) | Does integrated care improve treatment for depression? | Individuals with depression | Mental health and primary care | Integrated care planning | Integration | 1995–2006 | USA | 49 |

| Collet (2010) | Efficacy of integrated interventions combining psychiatric care and nursing home care for nursing home residents: A review of the literature | Nursing home clients with mental health concerns | Psychiatric care and nursing homes | Integrated interventions combining both psychiatric care and nursing home care in nursing home residents | Integration | 1996–2003 | Europe | 8 |

| Davies (2011) | A systematic review of integrated working between care homes and health care services | Nursing home patients with primary care needs | Healthcare services and care homes | Interventions designed to develop, promote or facilitate integrated working between care home or nursing home staff and healthcare practitioners | Integration | 1998–2008 | UK | 17 |

| Donald (2005) | Integrated versus non-integrated management and care for clients with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: A qualitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials | Mental health and substance abuse | Mental health and substance-use disorder | Integrated approaches are compared with non-integrated approaches for treatment of adults with co-occurring mental health and substance-use disorder | Integration | 1993–2001 | Australia | 10 |

| Dowling (2004) | Conceptualizing successful partnerships | General health and social care | Not described | Not described | Partnership | 1999–2003 | UK | 36 |

| Fisher (2012) | Health and social services integration: A review of concepts and models | Veterans | Veterans health and social care - general | Different approaches to services integration for the needs of veterans | Integration | 1993–2008 | USA | 76 |

| Fleury (2006) | Integrated service networks: The Quebec case | General – not specified | General – not specified | Not mentioned | Integration | 1961–2005 | Canada | 46* |

| Green (2014) | Cross sector collaboration in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood obesity: A systematic integrative review and theory-based synthesis | Indigenous children with disability | Health, education and social services | Inter- and intra- sector collaboration in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood disability | Collaboration | 2001–2014 | Australia | 18 |

| Grenfell (2013) | Tuberculosis, injecting drug use and integrated HIV-TB care: A review of the literature | Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), injecting drug user (IDU) with Potential for Tuberculosis (TB) | Health, substance abuse and social services | Governmental or non-governmental health or community-based services providing testing, prevention, treatment or other care for TB or HIV and TB, either directly or by referral. | Integration | 1995–2011 | UK | 87 |

| Hillier (2010) | A systematic review of collaborative models for health and education professionals working in school settings and implications for training | School-aged children | Education and health sectors related to children of school age | Interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary teams and any conclusions drawn about the knowledge or skills required by the professionals to promote these models. | Collaboration | 1980–2005 | Australia | 34 |

| Howarth (2006) | Education needs for integrated care: A literature review | Primary care | Primary care with social care | Education and training initiatives | Integration | 1995–2002 | UK | 25 |

| Hussain (2014) | Integrated models of care for medical inpatients with psychiatric disorders: A systematic review | Medicine in patients with psychiatric concerns | Health and mental health | Integrated models of care where psychiatrists and general medical physicians, either in isolation or in combination with other allied health staff, were integrated within a single team to provide care to an entire inpatient population. | Integration | 1997–2010 | Canada | 4 |

| Lee (2013) | What is needed to deliver collaborative care to address comorbidity more effectively for adults with a severe mental illness? | Mental health –Adults with comorbid concerns | Mental health, employment, forensic, homelessness, housing, physical health and substance abuse | Models that have addressed comorbidities to Severe Mental Illness, to demonstrate key principles needed to promote collaborative care. | Collaboration | 1995–2012 | Australia | 76* |

| Loader (2008) | Health informatics for older people: A review of ICT facilitated integrated care for older people | Older people with health conditions needing welfare support | Information technology, Computer science and health care (hospitals, clinics, laboratories, surgeries) and social and community agents (housing, voluntary and community groups, social services, carers, community nurses) | Dimensions of care as they were seen to relate to the modernising of adult social care objectives. | Integration | 1981–2005 | UK | 35* |

| Soto (2004) | Literature on integrated HIV care: A review | HIV and Substance Use Disorder (SUD) | Social services, mental health, and substance abuse | Integrated HIV care models HIV-infected clients and their use of ancillary services and integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment | Integration | 1990–2003 | USA | 47 |

| Winters (2015) | Interprofessional collaboration in mental health crisis response systems: A scoping review | Adult mental health crisis | Mental health, emergency department, police, pharmacy, traditional healers, university campus support | Studies that included an intervention or routine for the specific purpose of improving, measuring or exploring Interprofessional Collaborative Practice | Collaboration | 2000–2012 | Canada | 18 |

[i] * Indicates data that were not specified by the original author, but determined by the authors of the current study.

Table 4

Purpose and main findings of included review articles.

| Author | Title | Purpose | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butler (2011) | Does Integrated Care Improve Treatment for Depression? | To assess whether the level of integration of provider roles or care process affects clinical outcomes. | Although most trials showed positive effects, the degree of integration was not significantly related to depression outcomes. Integrated care appears to improve depression management in primary care patients, but questions remain about its specific form and implementation. |

| Collet (2010) | Efficacy of integrated interventions combining psychiatric care and nursing home care for nursing home residents: A review of the literature | Not stated | N = 8 (4 randomised controlled studies). Seven studies showed beneficial effects of a comprehensive, integrated multidisciplinary approach combining medical, psychiatric and nursing interventions on severe behavioural problems in nursing home patients. Important elements include a thorough assessment of psychiatric, medical and environmental causes as well as programmes for teaching behavioural management skills to nurses. DCD nursing home patients were found to benefit from short-term mental hospital admission. |

| Davies (2011) | A systematic review of integrated working between care homes and health care services | To evaluate the different integrated approaches to healthcare services supporting older people in care homes and identify barriers and facilitators to integrated working | Most quantitative studies reported limited effects of the intervention; there was insufficient information to evaluate cost. Facilitators to integrated working included care home managers’ support and protected time for staff training. Studies with the potential for integrated working were longer in duration. Limited evidence about what the outcomes of different approaches to integrated care between health service and care homes might be. The majority of studies only achieved integrated working at the patient level of care and the focus on health service-defined problems and outcome measures did not incorporate the priorities of residents or acknowledge the skills of care home staff |

| Donald (2005) | Integrated versus non-integrated management and care for clients with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: A qualitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials | To examine integrated treatment approaches versus non-integrated treatment approaches for people with co-occurring mental health/substance use disorders in order to investigate whether integrated treatment approaches produce significantly better outcomes on measures of psychiatric symptomatology and/ or reduction in substance use | The findings are equivocal with regard to the superior efficacy of integrated approaches to treatment. Clearly, this is an extremely challenging client group to engage and maintain in intervention research, and the complexity and variability of the problems render control particularly difficult. The lack of available evidence to support the superiority of integration is discussed in relation to these challenges |

| Dowling (2004) | Conceptualizing successful partnerships | To review literature published in the United Kingdom since 1997 to examine the success of partnerships in the healthcare and social care fields. To discuss the definitional and methodological problems of evaluating success in the context of partnerships before proposing approaches to conceptualising successful partnerships | Research into partnerships has centred heavily on process issues, while much less emphasis has been given to outcome success. If social welfare policy is to be more concerned with improving service delivery and user outcomes than with the internal mechanics of administrative structures and decision making, this is a knowledge gap that urgently needs to be filled |

| Fisher (2012) | Health and social services integration: A review of concepts and models | The immediate goal of this review of literature is to (a) trace the various definitions and uses of the concept; (b) explain the rationales for services integration; (c) describe how the concept has been utilised theoretically and in practice and provide examples of services integration models; (d) discuss factors that have been found to facilitate or challenge services integration as learned from these applications and (e) inform future development or improvement of policy and related programmes coordinating services and providing outreach to populations in need | Veterans’ services integration models along with inter-organisational relationship (e.g., network) models are common in the literature. Models range from centralised government agency initiatives to less formalised community-based networks of care. Findings from this review of literature may be particularly important to organisations that work with veterans, homeless, chronically ill and aging populations, whose needs often span a number of service areas and who often face multiple delivery systems that heretofore may not have effectively coordinated their services with others |

| Fleury (2006) | Integrated service networks: The Quebec case | On the basis of a review of publications on services integration and inter-organisational relations and on the Quebec context of healthcare reform, this article aims at generating a greater understanding of the concept of integration and certain underlying issues such as the effectiveness of models | Integrated service networks form of system structuring is one of the main solutions for enhancing efficiency, especially for clientele with complex or chronic health problems. Nevertheless, integrated service networks have lately been highly criticised for their inability to promote better system efficiency, which might be explained by a lack of knowledge in defining models and implementation difficulties. Parameters for organising integrated service networks, either virtual or vertical, have been strongly articulated in response to the lack of knowledge on that notion. The importance of integration strategies and the density of inter-organisational exchange in the network as well as the critical role of governance have been particularly outlined. Finally, information is still lacking on the following topics: effective models and strategies for developing integrated service networks; levels of density and centrality required in a network to achieve better results; clientele’s needs assessment in terms of services and levels of continuity and their influence on network modelling; impact of integrated service network models on system effectiveness, and clientele health and well-being. Impact assessment on integrated services network is central, but the level of reform implementation needs to be evaluated before measuring that impact (the black box effect.) The literature on network implementation and change stresses the importance of investing time and energy in developing tangible strategies to support a reform |

| Green (2014) | Cross sector collaboration in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood obesity: a systematic integrative review and theory-based synthesis | To identify important components involved in inter-and intra-sector collaboration in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood disability | Structure of government departments and agencies. The siloed structure of health, education and social service departments and agencies was found to impede service integration and the ability of providers to work collaboratively. Policies collaboration at the level of policy making can address the barriers generated by existing structures of government departments and agencies. Formalised agreements like memoranda of understanding and collaborative frameworks between government sectors can facilitate collaboration at the level of service provision. Communication – Lack of awareness can lead to duplication of resources. Raising awareness of collaborative partnerships through the distribution of educational resources across agencies and services facilitates collaboration. Lack of role clarity and responsibility, ambiguity and lack of role clarity and responsibilities of different providers, agencies and organisations is a key barrier to collaboration. Financial and human resources providing service when resources are limited is a barrier and often are done so ‘on sheer good will’ with staff often working beyond their normal hours. Service delivery setting: The effectiveness of a collaborative programme is influenced by the setting in which it is delivered. Relationships: A key facilitator to collaboration at this level is the coordinator or linking role. The appointment of a person external to the services or agencies involved whose role is to link the different players and act as a trainer, motivator and sustainer can be important to a collaborative interdisciplinary approach. Inter- and intra-professional learning: The modelling of inter- and intra-professional collaboration by clinical educators from different disciplines for university students on placement has been reported to facilitate a well-coordinated and holistic approach to learning |

| Grenfell (2013) | Tuberculosis, injecting drug use and integrated HIV-TB care: A review of the literature | This study builds on a recent review of tuberculosis among people who use drugs (Deiss et al., 2009) but focuses specifically on persons who inject drugs, a socially marginalised group with complex treatment needs. Specifically, to (1) describe the prevalence, incidence and risk factors for tuberculosis, Multidrug Resistance (MDR)-tuberculosis, and HIV-tuberculosis and HCV– HIV tuberculosis co-infections among persons who inject drugs and (2) identify models of tuberculosis and HIV tuberculosis care for persons who inject drugs | Latent tuberculosis infection prevalence was high and active disease more common among HIV-positive persons who inject drugs. Data on multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and coinfections among persons who inject drugs were scarce. Models of tuberculosis care fell into six categories: screening and prevention within HIV-risk studies; prevention at TB clinics; screening and prevention within needle-and-syringe-exchange and drug treatment programmes; pharmacy-based tuberculosis treatment; tuberculosis service-led care with harm reduction/drug treatment programmes; and TB treatment within drug treatment programmes. Co-location with needle-and-syringe-exchange and opioid substitution therapy, combined with incentives, consistently improved screening and prevention uptake. Small-scale combined TB treatment and opioid substitution therapy achieved good adherence in diverse settings. Successful interventions involved collaboration across services, a client-centred approach and provision of social care. Grey literature highlighted key components: co-located services, provision of drug treatment, multidisciplinary staff training; and remaining barriers: staffing inefficiencies, inadequate funding, police interference, and limited opioid substitution therapy availability. Integration with drug treatment improves persons who inject drugs engagement in TB services but there is a need to document approaches to HIV-TB care, improve surveillance of TB and co-infections among persons who inject drugs and advocate for improved opioid substitution therapy availability |

| Hillier (2010) | A systematic review of collaborative models for health and education professionals working in school settings and implications for training | Search of the literature to reveal the rudimentary state of the art in conceptualising, measuring and demonstrating the success of partnerships | Models of interaction and teamwork are well described, but not necessarily well evaluated, in the intersection between schools and health agencies. They include a spectrum from consultative to collaborative and interactive teaming. It is suggested that professionals may not be adequately skilled in, or knowledgeable about, team work processes or the unique roles each group can play in collaborations around the health needs of school children |

| Howarth (2006) | Education needs for integrated care: A literature review | To identify and critically appraise the evidence base in relation to education needed to support future workforce development within a primary care and to promote the effective delivery of integrated health and social care services | Six themes were identified which indicate essential elements needed for integrated care. The need for effective communication between professional groups within teams and an emphasis on role awareness are central to the success of integrated services. In addition, education about the importance of partnership working and the need for professionals to develop skills in relation to practice development and leadership through professional and personal development are needed to support integrated working. Education that embeds essential attributes to integrated working is needed to advance nursing practice for interprofessional working |

| Hussain (2014) | Integrated models of care for medical inpatients with psychiatric disorders: A systematic review | To review the different models of integrated models of care for medical inpatients with psychiatric disorders and to examine the effects of integrated models of cares on mental health, medical and health service outcomes when compared with standard models of care | In two studies, integrated models of care improved psychiatric symptoms compared with those admitted to a general medical service. Two studies demonstrated reductions in length of stay with integrated models of cares compared with usual care. One study reported an improvement in functional outcomes and a decreased likelihood of long-term care admission associated with integrated models of care when compared with usual care. There is preliminary evidence that integrated models of care may improve a number of outcomes for medical inpatients with psychiatric disorders |

| Lee (2013) | What is needed to deliver collaborative care to address comorbidity more effectively for adults with a severe mental illness? | To identify Australian collaborative care models for adults with a severe mental illness, with a particular emphasis on models that have addressed comorbidities to a severe mental illness, to demonstrate key principles needed to promote collaborative care | A number of nationally implemented and local examples of collaborative care models were identified that have successfully delivered enhanced integration of care between clinical and non-clinical services. Several key principles for effective collaboration were also identified. Governmental and organisational promotion of and incentives for cross-sector collaboration is needed along with education for staff about comorbidity and the capacity of cross-sector agencies to work in collaboration to support shared clients. Enhanced communication has been achieved through mechanisms such as the co-location of staff from different agencies to enhance sharing of expertise and interagency continuity of care, shared treatment plans and client records and shared case review meetings. Promoting a ‘housing first approach’ with cross-sector services collaborating to stabilise housing as the basis for sustained clinical engagement has also been successful |

| Loader (2008) | Health informatics for older people: A review of information and communications technology facilitated integrated care for older people | To find examples of good practice and any evidence to support the high expectations and confidence in information and communications technology to effectively address the challenges of healthcare and social care of older people | The aspiration of information and communications technologies to reconcile competing models of care also foregrounds the importance of recognising that information and communications technologies are designed and diffused within a particular social context that can either stimulate its adoption or make it redundant. The fastest broadband network connection will be of little use if healthcare and social care professionals are not prepared to share information with each other, let alone allow access to older people wishing to participate in decisions about their care. Similarly, the most accessible website will be seldom used by older people if its information content is not perceived as relevant to the life experiences of the user. Thus, while information and communications technologies may be regarded as important tools for enabling the ‘modernisation’ objectives to be achieved, their effectiveness is crucially shaped by the outcome of debates about those objectives themselves. Information and communications technologies cannot be viewed as a means to reconcile such policy contradictions. Such confused rhetoric is only likely to produce expensive and ineffective health informatics outcomes. The contradictions will merely be encoded into the system. Despite the repeated policy claims for health informatics to facilitate integrated person-centred health and social care, there is little evidence in the literature review considered here that it has been realised |

| Soto (2004) | Literature on integrated HIVcare: A review | It presents the findings related to integrated HIV care models, the needs of HIV-infected clients and their use of ancillary services, and integrated mental health and substance-abuse treatment, as well as descriptions of innovative integrated HIV care programmes. With the goal of providing useful information to HIV service providers, programme managers, and policy makers, these findings are discussed, and directions for future research are offered | The few evaluations of integrated models tended to focus on measurements of engagement and retention in medical care, and their findings indicated an association between integrated HIV care and increased service utilisation. The majority of reviewed articles described integrated models operating in the field and various aspects of implementation and sustainability. Overall, they supported use of a wide range of primary and ancillary services delivered by a multidisciplinary team that employs a ‘biopsychosocial’ approach. Despite the lack of scientific knowledge regarding the effects of integrated HIV care, those wanting to optimise treatment for patients with multiple interacting disorders can gain useful and practical knowledge from this literature |

| Winters (2015) | Interprofessional collaboration in mental health crisis response systems: a scoping review | To rapidly map key contributions to knowledge, especially in areas that are complex or have not yet been reviewed comprehensively, to summarise and disseminate research findings and to identify gaps in the existing literature related to interprofessional collaboration in mental health crisis response systems | Support for interprofessional collaboration, quest for improved care delivery system, merging distinct visions of care and challenges to interprofessional collaboration. Lack of conceptual clarity, absent client perspectives, unequal representation across sectors and a young and emergent body of literature were found. Key concepts need better conceptualisation, and further empirical research is needed |

Table 5

Frequency of terms used interchangeably by authors of included studies.

| Butler | Collet | Davies | Donald | Dowling | Fisher | Fleury | Green | Grenfell | Hillier | Howarth | Lee | Loader | Hussain | Soto | Winters | Number of terms used | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alliance | ▪ | ▪ | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Client centred | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Collaborating/ion | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ * | ▪ | ▪ * | ▪ | ▪ * | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ * | 15 | |

| Consolidating/ion | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Coordinating/ion | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 11 | |||||

| Integrating/ion | ▪* | ▪ * | ▪ * | ▪ * | ▪ | ▪ * | ▪ * | ▪ | ▪ * | ▪ | ▪ * | ▪ | ▪ * | ▪ * | ▪ * | ▪ | 16 |

| Interdisciplinary | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 6 | ||||||||||

| Inter-organisational | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Inter-agency | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 4 | ||||||||||||

| Inter-sectorial | ▪ | ▪ | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Inter-professional | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 4 | ||||||||||||

| Joint ventures/ working/ initiative /care | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 8 | ||||||||

| Multi-agency | ▪ | ▪ | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Multidisciplinary | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 12 | ||||

| Multi-organisational | ▪ | ▪ | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Multi-professional | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Partnership | ▪ | ▪ * | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 10 | ||||||

| Spoke/Case management /coordination | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 11 | |||||

| Team | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 12 | ||||

| Teamwork | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 5 | |||||||||||

| Trans-disciplinary | ▪ | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Trans-organisational | ▪ | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Vertical integration | ▪ | ▪ | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Virtual integration | ▪ | ▪ | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Terms used per article | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 15 | 16 | 9 | 7 | 13 | 11 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 140 |

[i] *Indicates the primary term adopted by the authors.

Table 6

Definitions of primary concept used by authors of included studies.

| Author | Primary term | Definition provided |

|---|---|---|

| Butler (2011) | Integration | At the simplest level, integrated mental and physical health care occurs when mental health specialty and general medical care clinicians work together to address both the physical and mental health needs of their patients. Models of integrated care, sometimes called collaborative care, vary widely, but most include more than merely enhanced coordination of or communication between the clinicians responsible for the mental and physical health needs of their patients. Indeed, attempts to integrate provider roles emphasise parity and mutual respect for the two health components. At the same time, they include efforts to improve the process of care using evidence-based standards of care. |

| Collet (2010) | Integration | Not defined |

| Davies (2011) | Integration | Integration of service provision can be defined as ‘a single system of needs assessment, commissioning and/or service provision that aims to promote alignment and collaboration between the cure and care sectors (Rosen & Ham, 2008). There are different levels of integration between healthcare services (Kodner & Spreeuwenberg, 2002). In the context of integrated working with care homes, these can be summarised as: Patient/micro-level close collaboration between different healthcare professionals and care home staff, e.g. for the benefit of individual patients. Organisational/meso-level organisational or clinical structures and processes designed to enable teams and/or organisations to work collaboratively towards common goals (e.g. integrated health and social care teams). Strategic/macro-level integration of structures and processes that link organisations and support shared strategic planning and development, e.g. when healthcare services jointly fund initiatives in care homes (Bond, Gregson, & Atkinson, 1989 and The British Geriatrics Society, 1999). |

| Donald (2005) | Integration | There is considerable diversity concerning the definition of integration, and the extent of integration varies enormously across different studies and settings. For example, it is used to refer to treatment provided both by multi-professional teams and by individual providers. In general, integrated approaches refer to those where both the mental health disorder and the addictive disorder are treated simultaneously. Typically, this is regarded as requiring the treatment to take place within the same service by the same clinician. The nature of the integrated treatment should also be considered. If integration merely involves augmentation through the addition of either a standard mental health treatment component or a standard drug and alcohol treatment component, then it may be argued that this is not truly integrated. Rather it may be that an integrated treatment would directly acknowledge and address the presence of the comorbidity in terms of the tailoring of the treatment to the current status of the person and would treat the co-occurring nature of the disorders, which may involve making adjustment in one treatment to take account of the other. |

| Dowling (2004) | Partnership | For the purposes of the present article, the authors adopted the Audit Commission’s (1998) definition of partnership as a joint working arrangement where partners are otherwise independent bodies cooperating to achieve a common goal; this may involve the creation of new organisational structures or processes to plan and implement a joint programme, as well as sharing relevant information, risks and rewards. This definition is compatible with a wider range of terms than ‘partnership’, including similar terms such as ‘cooperation’ and ‘collaboration’. |

| Fisher (2012) | Integration | Not defined |

| Fleury (2006) | Integration | To paraphrase Leutz (1999) the term integration has put forward a large number of models concerning the organisation of services or types of intervention. All refer to ‘anything from the closer coordination of clinical care for individuals to the formation of managed care organisations that either own or contract for a wide range of medical and social support services’. |

| Green (2014) | Collaboration | Not defined |

| Grenfell (2013) | Integration | Not defined |

| Hillier (2010) | Collaboration | Not defined |

| Howarth (2006) | Integration | Not defined |

| Hussain (2014) | Integration | Collaborative or integrated mental health care has been defined as care delivered by general medical physicians working with psychiatrists and other allied health professionals to provide complementary services, patient education and management to improve mental health outcomes (Katon, Von Korff, & Lin, 1995). Integrated models of care are patient-centred, and they not only involve the psychiatrist as a consultant with co-location of psychiatric and medical services but also involve a shared responsibility for the care of all patients within a service. |

| Lee (2013) | Collaboration | Not defined |

| Loader (2008) | Integration | Not defined |

| Soto (2004) | Integration | For the purpose of this review, we offer the following working definition: Integrated HIV care combines HIV primary care with mental health and substance-abuse services into a single coordinated treatment programme that simultaneously, rather than in parallel or sequential fashion, addresses the clinical complexities associated with having multiple needs and conditions. |

| Winters (2015) | Collaboration | Craven and Bland (2006) ‘involving providers from different specialties, disciplines, or sectors working together to offer complementary services and mutual support, to ensure that individuals receive the most appropriate service from the most appropriate provider in the most suitable location, as quickly as necessary, and with minimal obstacles’. |

[i] Craven MA, Bland R. Better practices in collaborative mental health care: an analysis of the evidence base. Can J Psychiatry Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie 2006; 51: 7S–72S.

Leutz WN. Five laws for integrating medical and social services: lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. Milbank Quart 1999; 77: 77–110.

Rosen R, Ham C: Integrated Care: Lessons from Evidence and Experience. The Nuffield Trust for Research and Policy Studies in Health Services; 2008.

Kodner DL, Spreeuwenberg C: Integrated care: meaning, logic, applications, and implications – a discussion paper. International journal of integrated care 2002, 2[1]: 1–6.

Bond J, Gregson BA, Atkinson A: Measurement of Outcomes within a Multicentred Randomized Controlled Trial in the Evaluation of the Experimental NHS Nursing Homes. Age and Ageing 1989, 18: 292–302.

British Geriatrics Society: The Teaching Care Home – an option for professional training. Proceedings of a Joint BGS and RSAS AgeCare Conference held in February 1999 [http://www.bgs.org.uk/PDF%20Downloads/teaching_care_homes.pdf], accessed 080311.

Katon W, VonKorff M, Lin E, et al: Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines Impact on depression inprimarycare. JAmMedAssoc1995; 273: 1026–1031. Audit Commission [1998] A Fruitful Partnership: Effective Partnership Working. Audit Commission, London.