Introduction

In March 2021, several young Indigenous Bunong villagers in north-eastern Cambodia were arrested by environmental rangers while preparing their farms on Indigenous communal land overlapping with the Phnom Nam Lyr Wildlife Sanctuary. During one of these incidents, a young man tried to escape and was allegedly beaten.

Ministry of Environment rangers carried out the arrests, and the Mondulkiri Provincial Department of Environment posted the news of the arrests on Facebook, stating that the reason for the arrests was to enforce the protection of the Phnom Nam Lyr Wildlife Sanctuary. However, Bunong villagers from the affected Indigenous communities complained that the arrest violated the rights of Indigenous peoples to use their communal land for traditional agriculture. Community leaders traced these conflicts to the massive loss of communal land more than a decade earlier following the government’s allocation of over 17,000 hectares1 in Economic Land Concessions (ELCs) without consultation, leaving families dependent on unregistered land that overlaps with the protected area. Despite Cambodia’s adoption of the SDGs, which include targets for securing Indigenous land rights, formal recognition remains pending, and communities’ claims unprotected.

Bunong villagers pointed to the unequal treatment of ‘little people’ and ‘big people’ or companies, when it comes to forest protection. In fact, four of the five concessions were located in areas originally within Phnom Nam Lyr Wildlife Sanctuary. To accommodate the concessions, the government excised and reclassified more than 15,000 hectares from the Sanctuary via sub-decrees between 2008 and 2012 (Subedi 2012).2 Villagers were particularly angry that rubber companies were able to destroy incredibly large swathes of their forests with impunity, while Indigenous families were criminalized for cultivating their small swidden fields. The villagers also accused the rangers of inaction when they had reported deforestation by powerful outsiders to them. Unverified rumors circulated in the villages that the arrests were linked to a major environmental protection program funded by the European Union and a big international environmental NGO. In the villagers’ view, little had been done in recent years to effectively protect the forests, and the authorities now sought to demonstrate that they were acting. But as authorities finally took action, it was not to curb the activities of powerful outsiders logging on Indigenous lands. Instead, villagers complained that the ‘little people’, those relying on their communal forest land for sustenance, were the ones facing arrest and prosecution. This continued top-down approach contradicts the transformative vision of the SDGs, which calls for a people-centered and planet-sensitive economy that respects the rights and livelihoods of Indigenous communities (UNGA 2015). Members of the Bunong community insisted that protecting the forest was indeed very important to them. They asked, “Where were the conservation organizations when the concessions were granted? And where were the authorities when we asked them to help protect our forests? And why were they now cracking down on the Bunong who only made their traditional living from communal land?”

These questions highlight the community’s frustration and sense of abandonment by both conservation groups and local authorities and convey a sense of injustice felt by the Bunong villagers, suggesting that outside parties are only interested in forest protection when it serves their interests and neglect the Indigenous peoples’ relationship with their land. It further highlights not only the neglect of Bunong interests through the imposition of external conservation efforts that do not account for Indigenous practices, but also the detrimental impact of top-down development policies that disenfranchise forest-dependent communities. These policies formed part of an aggressive development strategy of the government in the 2000s involving dual processes: opening remote and forested parts of Cambodia to large-scale investment through concessions while simultaneously closing these same areas to Indigenous communities through the Protected Area System. While both processes dispossessed Indigenous communities, the rapid expansion of economic land concessions drew particularly sharp criticism from civil society, UN bodies and NGOs because of their immediate and devastating impact on local livelihoods (Subedi 2012; LICADHO and Cambodia Daily 2012).

In 2015, Cambodia adopted the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a universal set of measurable targets, to track progress and foster accountability, with the overarching aim of achieving a more sustainable and equitable future for all (UNGA 2015). While the SDG narrative suggests that sustainable livelihoods among forest-dependent communities could be integral to conservation and development, little has changed for Indigenous groups like the Bunong. Their practices continue to be perceived as underdeveloped and environmentally harmful and have been increasingly criminalized, reflecting broader patterns affecting Indigenous Peoples worldwide (IWGIA 2024). The case of the Bunong highlights the marked discrepancy between the SDGs’ global aspirations and actual policies in countries like Cambodia. Despite Cambodia’s formal embrace of these goals, which emphasize participation and equality, the unequal power dynamics between local communities, corporations, and the state continue to disadvantage Indigenous groups like the Bunong. This sentiment, captured in the notion of unequal treatment of ‘little people’ and ‘big people’ or companies, when it comes to forest protection, underscores how top-down approaches persist even within the framework of the SDGs.

This paper examines the overlooked consequences of displacement experienced by the Indigenous Bunong community in Cambodia, resulting from both economic land concessions and conservation projects. It demonstrates how these past interventions, though seemingly distinct, converge to systematically exclude the Bunong from their ancestral lands—even after Cambodia’s adoption of the SDGs. By analyzing these parallel processes, the paper reveals how development and conservation initiatives often violate Indigenous rights and livelihoods, functioning as two sides of the same coin. Although the SDG framework acknowledges Indigenous sustainable resource management, its failure to explicitly recognize Indigenous collective land tenure systems makes it easier for the government to disregard their customary land rights. Juxtaposing the SDGs with Bunong lived experiences, I show how international standards can overlook the power-laden political-economic context in countries like Cambodia, underscoring the need for more context-sensitive policies.

This article employs three interconnected lenses to examine the contrast between the SDGs’ aspirations for inclusive and sustainable development in Cambodia and the realities faced by Indigenous communities on the ground. First, a short institutional genealogy that traces the chronology and hierarchy of legal-policy documents prior to the SDGs; second, a political economy analysis; and third, an ethnographic case study that brings to light the lived experiences and challenges encountered by Indigenous peoples navigating the intersection of development, conservation, and their livelihoods.

This article is structured as follows: first, I review literature on the exclusion of Indigenous communities through large-scale forest enclosure for economic development and environmental purposes, focusing on state territorialization and elite capture. I then examine the promises and problems of the SDGs, arguing they are likely instrumentalized by the government to respond to international pressure through rhetoric and symbolism rather than substantive change. In this context, the SDGs function as an institutional epi-phenomenon—a discursive institutional layer that provides contemporary vocabulary and meaning-making without transforming the underlying arrangements that shape policy outcomes or protect common property institutions. Next, I explain the methods. I then trace the genealogy of Cambodia’s land governance framework prior to the SDGs, showing how legal and political structures historically entrenched these contradictions. Drawing on secondary sources, I construct a political economy of Indigenous exclusion to contextualize how Indigenous commons are reduced to ‘leftovers’ (Leemann and Tusing 2023). Commons refers to land held as common property and managed collectively by local institutions, with access determined by matrilineal descent. Through the ethnographic case of Bunong livelihood criminalization, I detail the complex, on-the-ground dynamics of livelihood change and the interdependence of development and conservation policies. I conclude with reflections on how narratives sustain dual forces of exclusion, with the SDGs feeding into government rhetoric while ‘development as usual’ continues.

Indigenous Exclusion and Sustainable Development Goals

Forest-based Indigenous livelihoods and customary land tenure have come under increasing pressure due to the large-scale enclosure of land by various actors for economic, political but also environmental purposes (Baird, 2011; Hall et al., 2011; Inthakoun and Kenney-Lazar, 2025, Bourdier, 2024, Liao and Agrawal, 2024). These processes of large-scale enclosure converge in complex ways to systematically exclude Indigenous communities from their commons, reflecting broader patterns of geographical imbalances, implementation gaps, and social consequences documented across global land grabbing research (Liao and Agrawal, 2024). State territorialization in Southeast Asia began politically with the establishment of colonial states, which brought European ideas of forestry and agricultural development to the densely forested tropics (Peluso and Vandergeest 2001). But it is the postcolonial states of Southeast Asia that have designated more territory as forest than ever before, resettled local and Indigenous shifting cultivators, and dispossessed them of their commons through state land expropriation (Fox et al., 2009). These measures against shifting cultivation and its criminalization have led to a faster decline than in other regions (Van Vliet et al., 2013).

The establishment of protected areas has also been seen as a coercive tool of state power through the territorialization of state peripheries, including Indigenous territories (Baird, 2009; Bassett and Gautier, 2014), a process which has also been understood as ‘green grabbing’” (Fairhead et al. 2012). Conservation initiatives, while seemingly positive, can become instruments of dispossession and control over land and resources, particularly affecting Indigenous and local communities by overlooking their existing multifunctional use of land (Neef et al. 2023). Increased pressure to change global conservation practices in a more ‘people-friendly’ direction has yielded commitments at least on paper (Benjaminsen and Bryceson 2012). However, recent state-led reforestation initiatives in Southeast Asia have systematically marginalized multifunctional land uses, most notably swidden cultivation, while reinforcing governmental territorialization and control over land, resources, and local communities (Pichler et al. 2021). In Cambodia, these very landscapes harbor some of the country’s most valuable remaining timber reserves, making them a focal point of intense government interest (Milne 2015). Research showed the regime’s leveraging of state power to seize commonly held natural resources, often diverting them towards elite accumulation at the expense of impoverished rural communities (Neef et al. 2013).

The link between development schemes such as ELCs and conservation projects in Cambodia has been documented. Large development projects such as land concessions and hydropower plants, which involve legal logging, are usually located in and around forested areas such as national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, enabling the large-scale laundering of high-quality timber from conservation areas (Milne 2015; 2022, Milne, Pak, and Sullivan 2015). Government functions such as patrolling by uniformed park rangers and law enforcement are usually carried out with the support of NGOs. In doing so, global conservation organizations have generously, if perhaps unwittingly, funded the territorial prerogatives of governments since the early 2000s (Milne, Pak, and Sullivan 2015; Milne et al. 2023).

In Cambodia, as in many countries, large-scale land acquisitions surged by the end of the years 2010 — building on processes that began in the late 1990s and draw on colonial-era practices of territorial control— sparking debate over their developmental desirability (Deininger 2011; Debonne et al. 2019). Cambodia has been a significant target for these investments, particularly in the realm of ELCs (LICADHO 2023). The Government discursively justified ELCs as land policy measures supporting national development, creating employment opportunities in rural areas, and restoring ‘degraded’ and ‘non-use’ land (Neef et al. 2013), a rhetoric that has been critically scrutinized in a number of ways (De Schutter 2011). Key for the case here is that such ‘unused’ land very often is in common use (Eitelberg et al. 2015; D’Odorico et al. 2017) and that the notion of ‘degraded’ land underappreciates the many services land can supply (Borras et al., 2011). Instead of proving the higher efficiency of larger-scale farm units, empirical evidence shows that small owner-producers outperform corporate farms in all but a few crops (Deininger and Byerlee 2012). Alleged positive effects such as employment or poverty reduction often did not materialize or were insufficient to compensate for lost opportunities (Nolte and Ostermeier 2017) and the impacts on local livelihood and land system were often deemed unacceptable (Friis et al. 2016).

The SDGs have been celebrated by UN agencies like UNDP as a vehicle for Indigenous communities to advance rights-based and self-determined development (UNDP 2016). Although the SDG framework itself sets out targets for poverty reduction, social inclusion, and environmental sustainability, it is principally various international bodies and Indigenous advocates who invoke the Goals to promise enhanced opportunities for political influence, cultural preservation, and economic empowerment (Bansal et al. 2023; Yap and Watene 2019). However, critics argue that the SDGs insufficiently address the specific needs and rights of Indigenous peoples, including cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, land rights, and self-determination (Poole 2018; Yap and Watene 2019; Virtanen, Siragusa, and Guttorm 2020). Local communities remain largely excluded from shaping development agendas, as governments retain dominance and selectively implement SDG principles (Horn and Grugel 2018). This lack of systemic change along economic and political axes undermines the SDGs’ transformative potential and instead favors ‘development as usual’ (Kothari et al. 2019; Larsen et al. 2022). The SDGs have also been critiqued for providing a new vocabulary of legitimacy that can exacerbate dispossession and inequalities, facilitating land and resource grabbing under the guise of sustainability (Larsen et al. 2022; Hope 2021; Ashukem 2020). Their focus on technical measurements, rather than root causes—including elite state capture—risks turning the SDGs into what Ferguson (1994) calls the “anti-politics machine,” where power relations are masked by technical solutions (Larsen et al. 2022).

Despite normative pressures from the international community, the Cambodian government has maintained a striking degree of autonomy, projected an image of reform while pursuing its own agenda (Milne 2013; Work et al. 2022). Seemingly inclusive initiatives, such as social land concessions, have served to instrumentalize international aid, legitimize displacement, and perpetuate injustices (Neef et al. 2013). This results in what Cock (2010: 243) describes as “a hybrid of largely rhetorical and symbolic acquiescence to democratic norms, built on the foundation of a patrimonial and highly predatory state structure.” As ‘soft law’ instruments, the SDGs leave states substantial discretion in implementation and are vulnerable to co-option for symbolic progress rather than substantive change (Lencucha et al. 2023). Cambodia’s SDG implementation has taken place within an increasingly restrictive political environment; the 2015 Law on Associations and Non-Governmental Organizations imposed severe constraints on civil society, granting authorities broad powers to restrict groups deemed not ‘politically neutral’ (Norén-Nilsson and Bourdier 2019). This legal framework, adopted months before Cambodia began SDG localization, effectively constrained the meaningful civil society participation that SDG implementation ostensibly requires, creating conditions where development policies could proceed with minimal genuine consultation with affected Indigenous communities.

In the Cambodian context, the SDGs risk functioning as an institutional epi-phenomenon—a discursive overlay that reframes existing power relations and exclusionary land policies in the language of global sustainability, without addressing the entrenched contradictions between development, conservation, and Indigenous commons governance. This critique aligns with broader concerns that the SDGs’ lack of binding enforcement and their focus on technical indicators can mask ongoing dispossession and the erosion of common property institutions (Haller and Lamatsch et al. 2023). Building on these findings, I argue in this article that the SDGs risk being used by the Cambodian ruling elite to mask parallel forms of exclusion and fail to protect Bunong interests in inclusive development. This critique is intended to sensitize the global development cooperation and global agenda-setting to the everyday power-laden contexts in which the propagated policies unfold.

Methods

I carried out ethnographic fieldwork in Bunong villages of Mondulkiri, Cambodia since 2010. Bu Sra Commune lies in Pechr Chenda District of Mondulkiri Province in northeastern Cambodia, bordering Vietnam. The area comprises seven villages predominantly inhabited by the Indigenous Bunong minority, whose traditional livelihood system combined rotational swidden cultivation with the gathering of non-timber forest products and animal husbandry. From 2010 to 2014, I dedicated a total of four months to immersive fieldwork, employing participant observation and semi-structured interviews and follow-up interviews as my primary data collection methods. This was followed by intermittent on-site and online follow-up research from 2016 to 2024. Interviews with key actors—including Indigenous cultivators, Indigenous leaders, government officials, concession management, NGO and OHCHR representatives and human rights lawyers—explored perceptions of policies towards swidden agriculture, experiences of land loss, agricultural change, deforestation, adaptive livelihood strategies, and Indigenous titling processes. I consulted databases and documents provided by NGOs and community leaders. All participants provided informed consent in accordance with institutional review protocols. To safeguard anonymity, interviewees and villages are referred to by generic descriptors and no personal identifiers are disclosed.

Cambodia’s Land Governance Framework and Indigenous Exclusion

Pre-SDG Institutional Foundations

Cambodia’s institutional framework for land governance represents a paradigmatic example of how legal apparatus can systematically facilitate dispossession while maintaining the appearance of rights protection. To grasp this framework, it is necessary to analyze the evolution of its legal system and the conflicting priorities it institutionalized well before the introduction of the Sustainable Development Goals. These pre-SDG laws and policies established formal mechanisms for recognizing Indigenous land rights in the context of state-led initiatives such as protected areas and economic land concessions, yet at the same time, the overall system facilitated large-scale land alienation and frequently disregarded the very rights it purported to protect.

Phnom Nam Lyr Wildlife Sanctuary was created in 1993,3 establishing the protected area framework that would later be used to constrain Indigenous agricultural practices. In 2001, the Land Law established the fundamental framework for modern land administration in Cambodia.4 Crucially, this law simultaneously introduced three distinct but overlapping mechanisms that would prove fundamentally contradictory in practice: provisions for Indigenous Communal Land Titles (ICLTs) under Article 23, Economic Land Concessions (ELCs) under Chapter 5, and the legal foundation for what would later become Social Land Concessions, creating parallel and often conflicting pathways for land allocation. The temporal sequence of implementing sub-decrees—Social Land Concessions (2003), Economic Land Concessions (2005), and Indigenous Communal Land Titling procedures (2009)5— is significant: mechanisms for allocating land to private companies and social purposes were prioritized and operationalized years before Indigenous land rights procedures were established. Cambodia signed the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007,6 creating international obligations to uphold Indigenous rights—obligations that were violated in practice. The 2008 Protected Areas Law further consolidated territorial control, establishing eight categories of protected areas and introducing zoning mechanisms that would restrict Indigenous land use.7

These contradictions are structurally embedded within Cambodia’s legal framework itself, rather than being the result of implementation failures (OHCHR 2021). The core issue is the government’s systematic breach of its own legal apparatus, or its prioritization of certain state land uses over others, disadvantaging Indigenous communities but also small-scale farmers (IFAD 2023; Leemann and Tusing 2023; Milne 2015, 2022; Tusing and Leemann, 2023).

The SDGs as Institutional Epi-phenomenon

When Cambodia adopted the SDGs in 2015, the institutional framework for large-scale land acquisition and protected area management was already fully operational. The land governance system embodied fundamental contradictions between development objectives and conservation mandates, Indigenous commons governance and state territorial control, and between international legal commitments and domestic policy implementation. While SDGs can influence national legislation and policies (Ruppel and Murray 2024), as ‘soft law’ instruments they grant states significant discretion and are vulnerable to co-option for symbolic progress, as discussed above.

Building on these insights, I advance the argument that in Cambodia, the SDGs function as an institutional epiphenomenon—a discursive layer that supplies contemporary vocabulary and meaning-making structures without transforming the underlying institutional arrangements that determine actual policy outcomes. Rather than addressing the fundamental contradictions within Cambodian land governance, the SDGs have provided the government with a new rhetorical framework that obscures these contradictions and enables continued dispossession.

In sum, these contradictions were institutionalized long before the SDGs, but the SDGs have provided new vocabulary for their continuation rather than addressing their structural causes, enabling the government to claim progress on sustainable development while maintaining established patterns of Indigenous exclusion.

Political Economy of Indigenous Commons Dispossession in Cambodia

Bunong Indigenous forest-based livelihoods, commons and customary land tenure

Indigenous peoples constitute between 1 to 2 percent of the national population, living mainly in Cambodia’s remote, previously forested upland regions (AIPP 2015). The Bunong are one of the most sizable among Cambodia’s 24 officially recognized Indigenous groups, living mainly in Mondulkiri Province and across the border in highland Vietnam (Scheer 2014; Condominas 1977). Their livelihoods have been intricately intertwined with expansive collective forest lands, reflecting a broader regional pattern where an estimated 14-34 millions of other swidden cultivators have thrived across Southeast Asia at the end of the twentieth century (Mertz et al., 2009; Padoch et al., 2007).

Within Bunong social structure, matrilineal descent groups, or /mpôôl/, play a pivotal role for the customary tenure system, the transmission of land rights and the governance of common-pool resources.8 Residence in Bunong society is uxorilocal, meaning that married couples live in the wife’s locality. A traditional Bunong village generally corresponds to a descent group.9 Members from the same matrilineage/village have access to village land (bri taem), understood as a form of commons, a shared resource managed collectively by the group. In Bunong language, the word bri both means land and forest. Within village commons, families can claim exclusive individual use rights only to cultivated swidden fields (mirr) and more recent fallows. Bri functions as common property: as fallowed swidden fields becomes overgrown, they revert back to common-pool resources, available for clearing by any village member.

As I will discuss in detail later, bri has become scarce due to the processes that are the focus of this paper, and there are hardly any fields left fallow anymore, hence a de facto privatization of village land has taken place in recent years.

In the 2000s, when forests were still abundant, Bunong families practiced rotational agriculture within the land of their descent group/village, or bri taem (Leemann 2021). Because forests were known to be the dwelling place of spirits, land use was governed by a complex system of institutions, and these restrictions and rules were common knowledge among older village members and passed down to younger generations. Bunong from outside the village could request to use the commons, which was usually granted. They had to consult with villagers about the restrictions they had to follow. Although outsiders were allowed to use village land, they could never claim that their swidden fields would become part of their own descent group.10 Villagers have a responsibility to take care of their bri taem, it is the land of their ancestors, it is also home to spirits – some of them peaceful, some of them aggressive – and the villagers have to know the institutions, make sure they follow all the rules and that all ceremonies are done properly. This ensures the support of the ancestors and spirits and avoids harm to the village in the form of disease, accidents or other misfortunes. This responsibility was never taken lightly.

Families would only clear a new swidden field, or mirr, where it was deemed appropriate (on the taboos, see Leemann and Nikles 2017). They grew a variety of crops, including upland rain-fed rice, corn, various vegetables and fruits, and tobacco. Rice was a particularly important crop, with each family planting not only several varieties of “mother” rice, but also an average of three varieties of early-harvest rice. The agricultural cycle was punctuated by numerous ceremonies to honor the rice spirits. During the fallow period, minimal or no labor was expended on the field, but the family previously cultivating a mirr retained primary rights to products such as bananas, pineapples, and other fruits, as well as vegetables, tobacco and thatch grass, until these resources declined in the re-growing forest. Fallow land could be used as common grazing grounds. Various types of medicinal plants, some of which were found for many years, could be collected by anyone without restriction.

Forests served as fertile grounds for foraging (such as bamboo, wild honey), hunting, fishing, and grazing livestock; Bunong from neighboring villages could generally access and utilize each other’s forests, demonstrating an extended system of commons and common-pool resource institutions. However, some activities, like resin collection or building more permanent structures for cattle and buffaloes, were restricted to one’s own village commons or required permission from another village, as this use was considered more permanent. Knowledge of the boundaries of village lands and sacred sites was passed down from one generation to the next as the young people were taught how to forage, hunt, fish, and graze animals. Conflicts over land were reportedly rare and resolved through established conflict resolution mechanisms (Backstrom et al. 2007), further highlighting the strength of these commons institutions.

The villagers interviewed expressed strong feelings of independence, contentment and peacefulness when referring to these forest-based livelihood activities (see also Leemann and Nikles 2017). While the general negative perception of swidden cultivation as a destructive and unproductive way of farming11 has put massive constraints and pressure on the Indigenous population throughout Cambodia for decades (Guérin 2007), these policies did not affect the Bunong communities under study in significant ways before the end of the 2000s.

This description is not meant to suggest that Bunong communities lived in isolation from the rest of the world or the country. On the contrary, the region’s major conflicts have left their mark on its history and place, reflected in various layers of placemaking due to war, displacement, and resettlement (Leemann 2021). However, even in the early 2000s, Bunong communities’ way of life as forest-dependent swidden cultivators remained viable in this remote, still densely forested area.

Turning Indigenous commons into plantations and protected areas

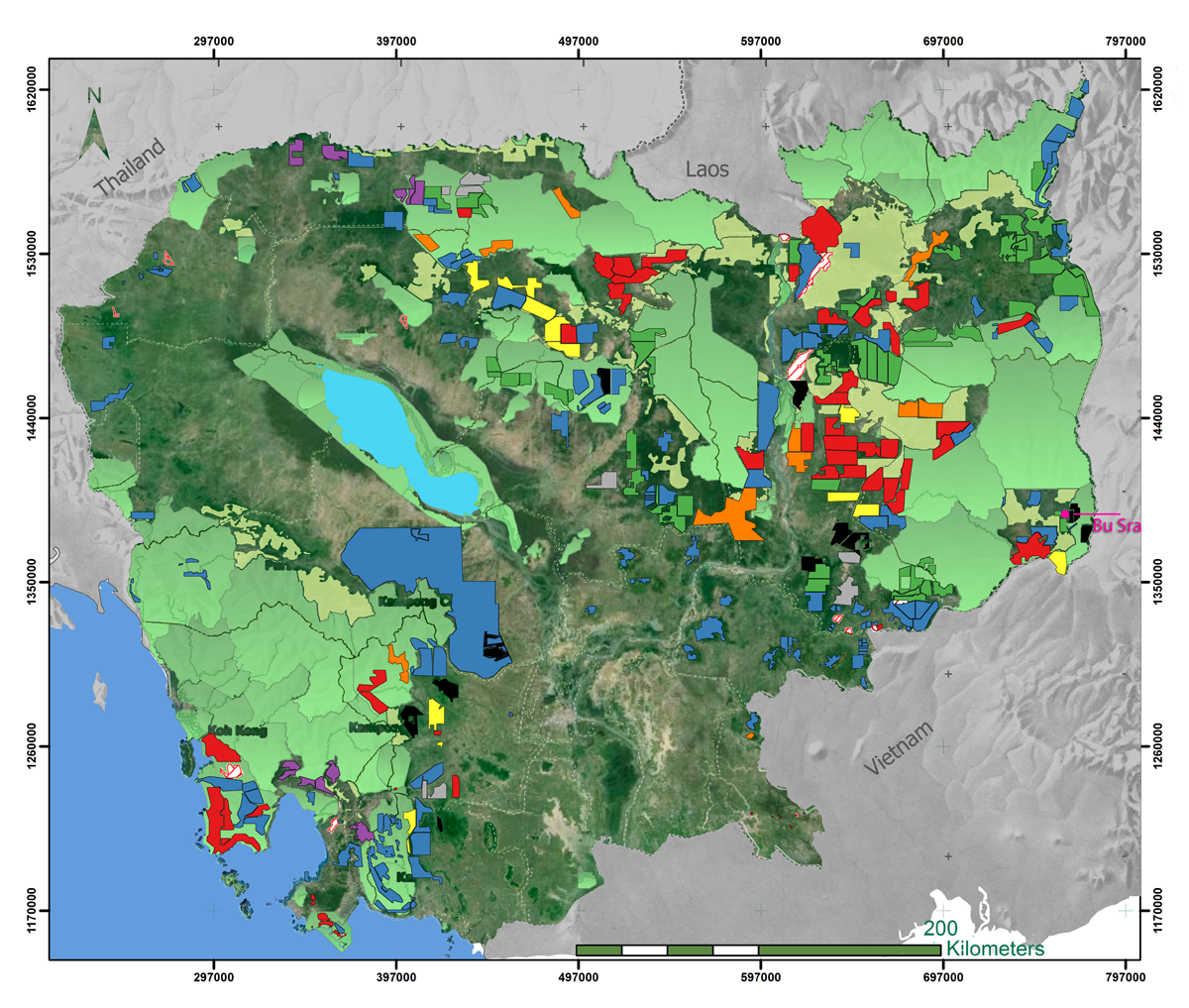

As in other Southeast Asian countries, the state territorialization of Indigenous territories in Cambodia was pursued through the creation of “political forest” (Peluso 1992). Since the 2000s, two trends have dominated Cambodia’s forests, both of which have led to the dispossession of Indigenous commons: Large-scale deforestation, driven primarily by economic development, and the establishment of protected areas, often justified by ecological imperatives (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Dual trend dominating Cambodia’s forests – Large-scale deforestation for economic ends and establishment of protected areas for conservation purposes. The areas of the ELCs are colored according to the countries of the concessionary companies: Blue is Cambodia, dark green Vietnamese, red Chinese, yellow Malay, purple Thai, grey Korean, orange Singapore and black is ‘other’. The areas of ‘Natural protected area’ are lighter green and those of ‘Biodiversity Conservation Corridor’ are the lightest green, having been integrated into the Protected Area system since 2023. Own map. Source: Google earth satellite image of forest cover in Cambodia 2024, Cambodia’s concessions in 2024 from LICADHO, Natural Protected Areas and Biodiversity Conservation Corridors in 2019 from Open Development Cambodia (ODC).

On the one hand, large tracts of forest have been converted into large-scale plantations. More than 300 ELCs12 covering more than two million hectares of land have been granted for agro-industrial purposes such as large-scale rubber, oil palm and sugar plantations (LICADHO 2023). In Mondulkiri province, 94,731 hectares have been granted as concessions for rubber plantations, of which almost one-fifth is in the case study site of Bu Sra commune (PCLMUP of Mondul Kiri Province 2021). Human rights organizations have strongly criticized these long-term leases,13 documenting the mass evictions, deforestation and rights violations they have caused. Only in 2012, after years of land conflicts and dispossession, Prime Minister Hun Sen declared a moratorium on ELCs (Order 01).14 Order 01 aimed to resolve land conflicts by granting titles to smallholders and reviewing concessions, but rubber companies in Bu Sra commune have been very reluctant to implement this policy (Chan et al. 2020). Critically, Order 01 failed to protect Indigenous communities by prioritizing individual over communal titles, undermining collective rights under the 2001 Land Law, leaving Indigenous communal lands vulnerable to further encroachment. Arguably, other mechanisms mobilized for land conflict resolution in Bu Sra commune—including company compensation schemes, mediation processes, and international litigation—have consolidated the presence of the ELC and perpetuated the exclusion of Bunong communities from their commons.

On the other hand, large areas of forest have been converted into large-scale conservation projects. Many forests were designated as protected areas in the early 1990s under the newly elected government following the peace agreements. For example, the Phnom Nam Lyr Wildlife Sanctuary was established in November 1993, covering an area of 47,000 hectares in Mondulkiri province (Subedi 2012). But it was not until the 2000s that the state, with the help of international conservation organizations, increasingly enforced the exclusion of Indigenous and other local populations (Milne 2022). Since 2012, protected area management has evolved toward zoning (core, conservation, sustainable use, community zones) to address competing claims to land and resources and benefit sharing.15 Yet Phnom Nam Lyr remains unzoned, creating ambiguity for Indigenous farmers. Recent post-SDG policies on community zones (Sub-decree 245 from 2022)16 and the 2023 Environmental Code17 —banning swidden agriculture in protected areas—further restrict Bunong livelihoods without resolving tenure insecurity.

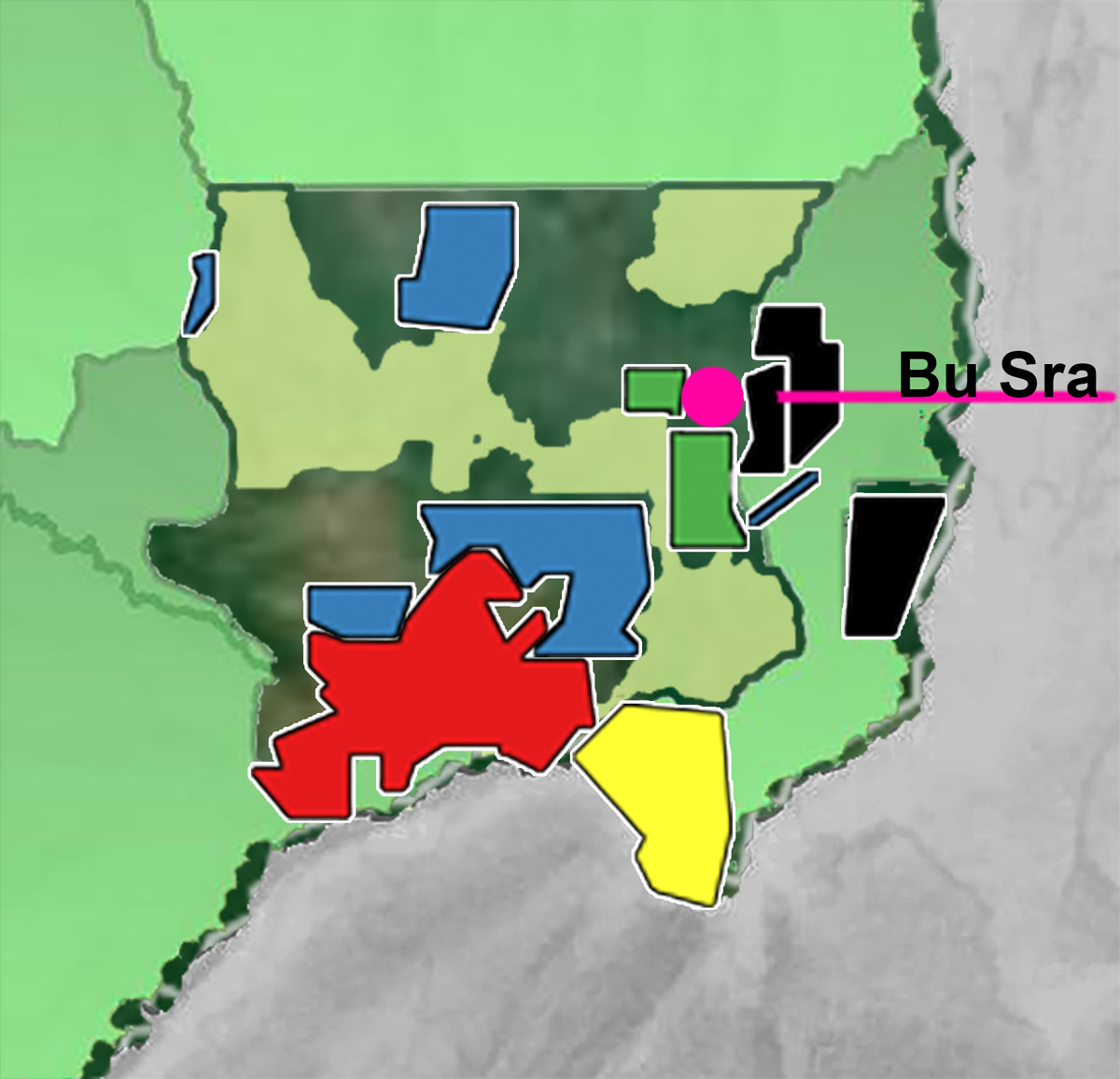

Both ELCs for corporate agro-industrial plantations on the one hand and protected areas on the other, cover the vast majority of Cambodia’s forests (see Figure 1). Notably, many ELCs are located in the core zone of protected areas, indicating that large-scale deforestation is occurring in areas that were originally designated for forest protection (Subedi 2012). The north-eastern province of Mondulkiri is a particularly vivid example of this dual trend, where the areas for ELCs and protected areas far exceed the areas available to the local, mainly Indigenous Bunong population for their livelihoods (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Indigenous Dispossession in Bu Sra Commune in Mondulkiri Province: Bunong communities are confined to leftovers only (satellite image, darkest green) from Economic Land Concessions (various colors) and Phnom Nam Lyr Wildlife Sanctuary (light green). The areas of the ELCs are colored according to the countries of the concessionary companies: Blue is Cambodia, dark green Vietnamese, red Chinese, yellow Malay, black is European. The areas of ‘Natural protected area’ are lighter green and those of ‘Biodiversity Conservation Corridor’ are the lightest green, having been integrated into the Protected Area system since 2023. Own map. Source: Google earth satellite image of forest cover in Cambodia 2024, Cambodia’s concessions in 2024 from LICADHO, Natural Protected Areas and Biodiversity Conservation Corridors in 2019 from Open Development Cambodia (ODC).

As depicted in Figure 2, Bunong communities are now confined to what can be described as “leftovers”—small, fragmented parcels of land that remain after the allocation of vast areas to Economic Land Concessions, protected areas, and other processes during years of land titling that further divide and marginalize Indigenous territories (Leemann and Tusing 2023).

SDGs and ‘Development as Usual’

According to the Global SDG Index 2022, Cambodia ranked 107 out of 163 countries, just below the regional average (UN SDCF 2023 p. 73). But recent UN reporting on progress towards SDGs stresses that Cambodia “is implementing environmental policies and governance reforms to transform the current mode of economic development into one that is more sustainable and better equipped to simultaneously ensure the needs of people and ecosystems” (UN CCA 2023, p. 38). It highlights that “the country still faces challenges in fully attaining this ambition” and that “there are challenges to fully realise community rights to access natural resources” (UN CCA 2023 p. 38). Nevertheless, it summarily attests that in terms of SDG 15 (Life on Land) “…Cambodia has made progress in slowing rates of deforestation and expanding protected areas to 41 per cent of total land” (UN SDCF 2023 p. 23).

Highly aggregated indicators obscure local realities, as seen in a recent case where an Indigenous community sought land title within a rubber concession overlapping the Phnom Nam Lyr Wildlife Sanctuary. While official reporting highlights Cambodia’s progress in expanding protected areas, these quantitative achievements mask the lived realities of overlapping land claims, unresolved tenure, and institutional contestation. By focusing on such metrics, SDG reporting enables the government to present an image of progress, even as these very designations perpetuate or legitimize the dispossession of Indigenous communities from their ancestral lands.

For example, in December 2023, Bunong villagers—supported by staff from the provincial land and environment departments and the district administration—surveyed their remaining land in pursuit of a collective land title (CLT). Community members also went into the rubber concession to survey plots for the CLT, which some families had received as compensation for lost land (for details on compensation, see Leemann and Tusing 2023). The survey team posted this activity on social media to show that the work for Indigenous land titles was progressing. The rubber company saw the post and subsequently filed a complaint against five of the Indigenous villagers recognizable in the photos, challenging the Indigenous land claim within the plantation. The district government called these five people to a meeting. At the meeting, the plantation management explained that the company had received the area as a concession from the government and could not allow people to survey the land. According to community members, the Environmental and Land Department officials did not agree on this issue. The Land Department officials sided with the villagers and shared the interpretation that the land within the concession that the villagers were using belonged to them and not to the company, so they could include it in the CLT. The Environmental Department officials sided with the company, saying that the villagers could only use the land, but could not own it as private or communal land because it would be concession land. The disagreement was not resolved at the meeting, further delaying the entire titling process, which has been dragging on since 2011. This incident illustrates how the fragmented and ambiguous institutional landscape governing land in Cambodia—contradictions not captured by UN aggregated reporting—enables the deferral of meaningful land security for Indigenous peoples.

On paper, Cambodia’s Indigenous communities have strong rights to land security, anchored in laws supporting collective forest management and land tenure. However, the government has only granted collective land tenure to 8% of the country’s Indigenous communities (to 36 communities, none in the study area) (ODC 2021, Chhuonvuoch 2022). Since the 2016 transfer of all protected areas to the Ministry of Environment, no Indigenous Communal Land Title has been issued within any protected area, as the ministry has effectively declined or indefinitely deferred every application at the final registration stage (Brook 2024). The highly complex and at the same time vague legal framework of Indigenous collective land titling has kept donors, international and national organizations busy with legal analysis, monitoring and advocacy, burdening them with providing substantial legal and technical support. Land titling thus absorbs those who seek to strengthen Indigenous collective land rights. In fact, the process of Indigenous land titling in Cambodia has created a particular nexus of social, political and capitalist relations in which Indigenous communities’ efforts are focused on obtaining collective titles and maintaining effective control over titled land. Meanwhile, after years of land titling efforts, only these “leftovers” (Leemann and Tusing 2023) are available for titling, with the rest of the territory allocated to state administration and market logics, including concessions, protected areas, and private property. This transformation, as Bourdier (2024) emphasizes, represents the conversion of forest peasants into market-dependent producers through the abandonment of traditional livelihoods in favor of monocrop plantations.

The incidence shows that Indigenous communities’ land claims are still contested by companies and provincial environmental department officials, that collective land titles can easily be blocked, interim protections under Sub-Decree 83 are never enforced, and only leftovers are available for Indigenous titling. The highly aggregate indicators used for UN reporting towards the realization of its national development ambitions and the SDGs cannot possibly capture these realities, leaving governments such as Cambodia ample space to continue with ‘development as usual’.

‘Development as Usual’ and its impact

Dispossession through rubber plantations

The impact of large-scale rubber plantations on the lives and futures of Indigenous peoples has been enormous: Bunong communities have not only lost fields, grazing land and forest resources. The bulldozers that cleared the forests within the concession area also partially or completely destroyed countless sacred forests and even burial grounds. It was only after protests and riots, complaints to the government and lengthy negotiations with company management that partial compensation was paid for the destruction of sacred sites and the desecration of burial grounds. Compensation for fields, grazing land, and forest resources was grossly inadequate (see Leemann and Tusing 2023). Bunong houses in villages were not relocated, but families had to leave their field huts and fields. And all that was familiar to the communities, their forest, their land, their fields and pastures, was changed beyond recognition. Since then, the communities have slowly rebuilt their lives after this great shock and fundamental uncertainty. They have adapted to the new challenges of being small farmers in the leftovers, changing but also retaining important socio-cultural characteristics and claiming opportunities for Indigenous lives and futures (see also Leemann and Nikles 2017).

Dispossession through conservation

The Phnom Nam Lyr Wildlife Sanctuary was established by royal decree in 1993 and covers 47,500 hectares, which overlaps significantly with the land of many Bunong lineages in Bu Sra commune. However, according to Bunong villagers, their customary resource and land use rights and livelihood activities, such as swidden cultivation, foraging, fishing, and hunting, were not restricted at that time. Between 2008 and 2012, through several sub-decrees, a total of 15,362 hectares (32%) of the Sanctuary were reclassified as state private land and designated as a sustainable use zone to be granted as ELCs for agro-industrial crops and rubber (Subedi 2012). Much of these ELCs overlapped with the Indigenous lands of the Bunong communities, violating their rights under the relevant legal frameworks, as has been repeatedly criticized by UN Special Rapporteurs (e.g. Subedi 2012).

While rubber companies have been legally allowed to clear the aforementioned 32% of the sanctuary—reclassified as state private land for ELCs—and logging has continued around concessions in the sanctuary, the livelihoods of Bunong communities have been increasingly restricted, with notorious disregard for their resource and land use rights. Since the early 2020s, the designation of Bunong commons as a protected area has led to the criminalization of their traditional livelihood practices, such as swidden cultivation and hunting. Interestingly, the arrests described above occurred in close proximity to ELCs controlled by a European company, totaling 12,000 hectares of rubber plantations. Arrests for forest protection often take place within or near their concessions. In early days of April 2021, a few weeks after the first arrests, two more young men were arrested in the same location. One had created a new field, and the other was working on a field that was in its third year after being cleared, so it was not a new field. The company also called in the rangers to stop five Bunong families inside the ELC. The families had begun planting new fields within the concession on so-called relocation land, allocated as partial compensation for lost fields (see Leemann and Tusing 2023). The new fields were allegedly too close to a stream and therefore in violation of environmental laws. The rangers did not arrest the five families, but they stopped them from planting new fields, severely affecting their livelihoods. For fear of being arrested by the rangers, many villagers did not go to their farms within the wildlife sanctuary, even though April is a critical time in the agricultural cycle when farmers should be preparing their fields for planting.

While hunting and logging are strictly forbidden, conservationist organizations encourage the collection of honey, resin and medicinal plants as viable livelihood alternatives. However, with a third of the Phnom Nam Lyr Wildlife Sanctuary lost to rubber plantations, forest resources are much scarcer and not within easy reach. There is a gap between Indigenous realities and environmental narratives where NTFP collection is promoted as sustainable—with conservation organizations claiming honey collection could generate millions in revenue (The Phnom Penh Post 2024)—but villagers counter that it depends on deep forests and is seasonal only. Moreover, livelihood strategies vary significantly within villages: most families previously focused on swidden agriculture, some on livestock, and only a few on foraging. While some families may still generate income from collecting honey, resin, and rattan, villagers report losing many resin trees to continued logging. For the majority of families, without agricultural land, ‘conservation cum development’ schemes (i.e. combined conservation and development efforts) cannot generate viable outcomes, as NTFP collection cannot compensate for economic losses from banned agriculture and other livelihood activities. With cultivation and grazing rights denied, illegal logging becomes an important financial option for young men. As discussed above, the SDGs’ omission of common property and collective rights continues to shape the everyday vulnerabilities experienced by Bunong communities.

Besides the large-scale dispossession of Bunong communities through the ELCs, the opening of the area to rubber plantations in 2008 triggered an influx of smallholders from the lowlands in search of labor and land. For them, cassava was an attractive way to claim newly cleared land, as in other upland frontier regions (see Mahanty and Milne 2016). Also, logging in and around the ELCs has been ongoing since large-scale deforestation within the concession areas began in 2008. Moreover, investors from the provincial and even the national capital, who have been able to secure private land titles due to their good relations with government officials or because they are officials themselves, have bought or simply seized significant tracts of land for rubber plantations and, more recently, for tourist resorts, further increasing demand and competition for land. Stakeholders here include district and provincial officials, border police, and military commanders, a pattern familiar from other frontier forests in Cambodia (Diepart and Sem 2018; Hayward and Diepart 2021; Milne 2015; Milne and Mahanty 2017). These parallel processes, in which critical elements and relationships come together as a ‘conjuncture’ (Li 1996), put enormous pressure on the resources used by Bunong communities.

Living in the leftovers: Livelihood changes in Bunong communities

The processes of dispossession resulted in a dramatic shortage of land available for Indigenous swidden livelihoods, and SDG adoption left these policies unchanged. As land became scarce and communities struggled to secure remaining land through legal means or land titling, traditional rotating cultivation and fallow periods were abandoned for permanent agriculture, disrupting soil fertility reproduction characteristic of swidden systems. Permanent cultivation—planting cash crops like rubber or coffee—served as markers of land occupation, helping communities demonstrate rights where land was contested by elite capture and lowland migration (Leemann and Nikles 2017).

Bunong families who lost their fields to the ELCs or through distress sales have had little choice but to clear forests outside the concession areas on pre-war Indigenous commons overlapping with the Phnom Nam Lyr Wildlife Sanctuary, or the Biodiversity Corridor areas, that were established after the adoption of the SDGs in 2016. These small-scale deforestations in protected areas were tolerated by the authorities during and after the establishment of large-scale rubber plantations, most likely because the Bunong families established their new fields at a strategic distance from logging operations in which government officials were allegedly involved. These families too would cultivate their newly cleared fields permanently to mark that the land had been taken.

Customary collective land and forest tenure arrangements transformed rapidly. In Bu Sra commune, almost all Bunong families practiced swidden farming in 2008, but by 2020, only 34 of 1,079 families (3%) maintained swidden fields (total family numbers are drawn from 2008 and 2020 commune census records, practitioners from own field surveys). Swidden agriculture, a key marker of Bunong identity, became unfeasible (Leemann and Tusing 2023). This agricultural change has been accompanied by the de facto privatization of the Bunong commons. This shift to permanent cash crops exposed households to new vulnerabilities through substantial upfront investments, microloans using remaining land as collateral—though not legally permitted—creating heavy indebtedness for some.

As land for swidden agriculture dwindled, and the loss of commons access meant that forest-based activities—hunting, gathering, and collecting non-timber forest products—were no longer viable supplementary income sources, Bunong villagers also pursued other coping strategies than agriculture. Job migration, although still limited, became more common, particularly among young adults. Many resorted to wage labor in Bu Sra commune, though employment opportunities remained severely limited. Crucially, plantation companies predominantly hired laborers from lowland provinces rather than locals, with skilled supervisors often from the lowland or Vietnam. This practice contradicted government claims that ELCs would create local employment. Plantation work, when available, offered only sporadic employment for Bunong villagers at low wages.

Narratives concealing development and conservation impacts

Not only do the two processes of exclusion have very similar negative impacts on the Indigenous population, but they are also discursively justified by reference to each other. Legitimation processes (Hall et al. 2011) are critical to the enactment of land appropriation for both economic and environmental purposes. The Cambodian government can claim to care about the environment by designating large areas as protected, while at the same time compensating for the destruction caused by the ELCs it grants. There is symbolic value in this ‘economy of repair’ (Fairhead et al. 2012), which was originally intended to curb both growth and environmental damage. However, the neoliberal turn in conservation has proved attractive to both those responsible for environmental damage and the conservation organizations seeking to protect these increasingly commodified ecosystems. Conservation then facilitates the justification of ELC policies and the expansion of large-scale plantations, and the moral weight of a global green agenda to save the world legitimizes enclosures or green ends and trumps local livelihood concerns.

Just as the narratives that legitimize ELCs in Cambodia portray forest areas as ‘idle’ and ‘unoccupied’ land, green discourses tend to use images of ‘marginal land’ and ‘last pristine forests’ that obscure people, livelihoods, and their relationships to the environment. When local communities are mentioned in economic narratives, they are portrayed as poor, backward, and in need of modernization and development through large-scale investment. Green discourses often reiterate the old narrative of swidden cultivators as backward, constructing them as destroyers of the environment and justifying their removal, restriction or re-education (Leach and Mearns 1996). Yet Indigenous peoples are often depicted as somehow closer to nature. The Bunong have been portrayed as ‚caretakers of the forest‘ (FFI 2007), emphasizing the social and cultural importance of spirit forests, burial grounds in the forest, and the dependence of communities on the collection of non-timber forest products, while making only passing reference to swidden cultivation, a key feature of Bunong livelihoods.

In several Bunong communities in Mondulkiri province, village leaders have used their power to make deals with business interests and government officials, signing away commons and excluding more vulnerable households from any share in ‘benefits’. Such incidents expose the fallacy underpinning many conservation and development policies, which treat communities as unified collectives. These policies promise ‘pro-poor’, ‘benefit-sharing’ and ‘win-win’ opportunities (Fairhead et al. 2012) yet tend to ignore political dynamics and processes of inequality and exclusion within communities. As Li (1996: 505) argued, “addressing distributional questions adequately and formulating appropriately fine-tuned policies and interventions require a closer look at what and who, exactly, is ‘the community’”. In practice, negotiations over resource use and management demand specialized knowledge, organization, and influence—capacities that are unevenly distributed and often inaccessible to the most marginalized (Leemann 2021). Consequently, idealized images of “the community” serve as poor and misleading guides for actual translation into operational strategies and programs in development and conservation alike.

The exclusionary development and conservation policies described above, which have led to the dual process of dispossession with enormous impacts on Indigenous people’s lives and livelihoods, were largely in place before the SDGs were introduced into Cambodia’s policy framework. However, as the case from the Phnom Nam Lyr Wildlife Sanctuary area shows, the SDGs have not changed these configurations in favor of Indigenous communities. The old narratives are not being discontinued, they are simply being complemented by the new SDG discourse that sees Indigenous peoples as agents of change in envisioning “a world that is more inclusive, sustainable, peaceful and prosperous, and free from discrimination based on race, ethnicity, cultural identity or disability” (ILO 2016, p.10).

Conclusion

The paper highlighted the tensions between the vision of the SDGs and actual policy. Although the SDG framework informs government policy on paper, the case of Indigenous communities overlapping both with ELCs and Phnom Nam Lyr Wildlife Sanctuary showed that there has been no fundamental shift in policy and power dynamics on the ground. I argued that the role of the SDGs in achieving inclusive and equitable sustainable development for Indigenous peoples such as the Bunong needs to be questioned. As I showed, both policies, ELC and environmental protection measures, including the associated side effects, have strongly influenced the availability of Indigenous commons. While vast areas of the protected zone have been rezoned and rubber plantations made available, Bunong villages have been surrounded by ELCs and wildlife sanctuaries, and important aspects of traditional livelihoods such as swidden cultivation and hunting are criminalized. Livelihoods and social, cultural and religious aspects of Indigenous ways of life have changed dramatically over the past few years. Only very few families still practice shifting cultivation. The remaining forest offers fewer resources for foraging. Indigenous rights under the relevant legal framework are continuously disregarded. The legal protection of Indigenous land claims through land titling has kept organizations and communities busy, but as the latest developments on the ground show, they continue to be blocked.

The Bunong case underscores the need to critically assess the SDG narrative to ensure it promotes, rather than undermines, Indigenous rights and self-determined development. The SDGs’ failure to explicitly recognize Indigenous collective land tenure systems is a missed opportunity; such recognition would empower Indigenous communities to claim their rights. Without it, the SDGs risk reinforcing existing power imbalances and undermining their own goals.

This is particularly important in a context such as Cambodia, where the government has perfected the art of offering lip service under international pressure while maintaining its exclusionary development agenda. By projecting an image of reform, the ruling elite strategically deploy seemingly inclusive initiatives such as Indigenous Land Titling to leverage international aid while advancing their own interests. In this context, the SDGs function as an institutional epi-phenomenon—a discursive institutional layer that supplies contemporary vocabulary and meaning-making structures without transforming the underlying arrangements that determine actual policy outcomes or protect common property institutions—and, as I have argued in this paper, they risk being appropriated by Cambodia’s ruling elite to mask exclusionary practices and undermine the inclusive development aspirations of the Bunong people.

This critique aims to encourage both, the development and conservation community, to engage more critically with the power-laden Cambodian context. It is unsettling that conservation organizations were not more engaged in challenging the government’s ELC policy to protect tens of thousands of hectares of forest and wildlife habitats, but instead focus on the exclusion of powerless local communities. As Milne (2022) has shown in her insider ethnography in one of the conservation organizations active in Cambodia, conservation NGOs have often failed to challenge government ELC policy or protect forest and wildlife habitats, instead focusing on the exclusion of powerless local communities. Milne and media reports denounced rampant logging under the watch of the conservation organization, involving elite interests, government officials, and park rangers financed by the organization. But instead of calling out these activities and changing its procedures and policies, the organization covered up the scandal and turned against those who revealed it. It is high time for all actors in the conservation and development community to engage seriously with existing critiques.

Bunong villagers criticize the continuation of ‘development as usual’ as the same old favoritism for big people at the expense of small people. A fundamental change addressing root causes of exclusionary development would require recognition of Indigenous rights to self-determination and consistent support for Indigenous claims to land and forest-based livelihoods. This means development and conservation actors must support Indigenous land titling, protest large-scale deforestation, and confront government, elite, and transnational business interests—rather than focusing narrowly on technical indicators or rhetorical narratives. Achieving this will require ongoing self-reflection and an honest engagement with power relations and political realities in Cambodia. For the SDGs to fulfill their promise of inclusive and equitable development, they must move beyond technical indicators to confront the structural roots of exclusion and dispossession. Only then can the SDGs become a genuine catalyst for Indigenous rights and sustainable futures, rather than serving as a discursive shield for development as usual.

Notes

[1] The European holding company SOCFIN operates three economic land concessions (Varanasi, Sethikula and Coviphama) totaling 12,440 hectares via its subsidiary SocfinASIA and two operating companies (Socfin-KCD and PNS LTD). By operating through separate legal entities, this structure formally complies with legal requirements: individual concessions must not exceed 10,000 hectares, and no single entity may hold multiple concessions totaling more than this limit. The Vietnamese DAK LAK has received economic concession land totaling 4,162 hectares and the Cambodian KPEACE 522 hectares. In addition, a so-called Social Land Concession (SLC) covers 2,400 hectares on paper but has been informally extended (Subedi 2012).

[2] Only DAK LAK concession lies entirely outside the original sanctuary boundaries. Varanasi, Sethikula, Coviphama and K Peace concessions were excised via sub-decrees that reclassified 15,362 ha (32% of the sanctuary) as state private land for ELCs between 2008-2012 (Subedi 2012: 105–106).

[5] Sub-Decree on Social Land Concessions, No. 19 ANK/BK, 19 March 2003, Royal Government of Cambodia; Sub-Decree on Economic Land Concessions, No. 146 ANK/BK, 27 December 2005, Royal Government of Cambodia; Sub-Decree on Procedures of Registration of Land of Indigenous Communities, No. 83 ANK/BK, 9 June 2009, Royal Government of Cambodia.

[8] In a matrilineal descent system, a person is considered to be from the same descent group as his or her mother. The terms “descent group,” “matriline,” and “lineage” are used interchangeably here.

[9] Because of post-war resettlement in the 1980s, some Bunong villages consists of two or more matrilineal decent groups, referred to as sub-villages by Khmer government officials, each with its own (sub-)village land. Only a joining ceremony between two decent groups allow families to use each other’s (sub-)village land (see Leemann 2021).

[10] Mertz et al. (2009, 261) define swidden cultivation as “a land use system that employs a natural or improved fallow phase which is longer than the cultivation phase of annual crops, sufficiently long to be dominated by woody vegetation, and cleared by means of fire.”

[11] Dominant rural policy discourses consider swidden agriculture to be an unsustainable land use and destructive to forests (Mertz and Bruun 2017, Dressler et al. 2017). Most national, but also international and regional policies have therefore pushed and continue to push for the replacement of swidden with other land uses (Dressler et al. 2017). However, anthropological studies provide evidence that swidden agriculture is in fact a sustainable way of farming, provided that farmers maintain the required length of fallow periods (e.g. Cairns 2015, Conklin 1957).

[12] Economic land concessions (ELCs) cover areas of up to 10,000 hectares and are granted to national and foreign companies. The legal framework for ELCs is Sub decree no. 146 on Economic Land Concessions, which limits the allocation to state-owned land. The 2001 Land Law introduced a new categorization system, namely state-public land (state-owned, public use), state-private land (state-owned, but can be granted as concessions), private-individual land (with possession and ownership to land), and Indigenous/community land (for Indigenous communities practicing shifting cultivation).

[13] ELCs were granted for an initial period of up to 99 years, but since 2007 for a maximum of 50 years according to the Civil Code (Article 247). Concessionaires have exclusive rights to use the land, i.e. it is withdrawn from the population for several generations.

[14] Despite the moratorium, however, the government awarded a ELC in 2022 for the first time in ten years. The Ministry of Environment (MoE) granted 5,602 hectares of land in a biodiversity corridor in Stung Treng Province, a protected area managed by the MoE, to a Korean company, which transferred the concession to a Cambodian company shortly afterwards (CamboJA News, 16 January 2023).

[15] Zoning Guidelines for the Protected Areas in Cambodia, Ministry of Environment, 2 October 2017, Royal Government of Cambodia.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank her Bunong interlocutors and her local research collaborator, Prak Neth for his invaluable contribution. She also thanks the editors and anonymous reviewers for their careful reading, constructive criticism, and feedback on earlier versions of this paper.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Author Contributions

The author Esther Leemann conducted the research, analysis, and writing.