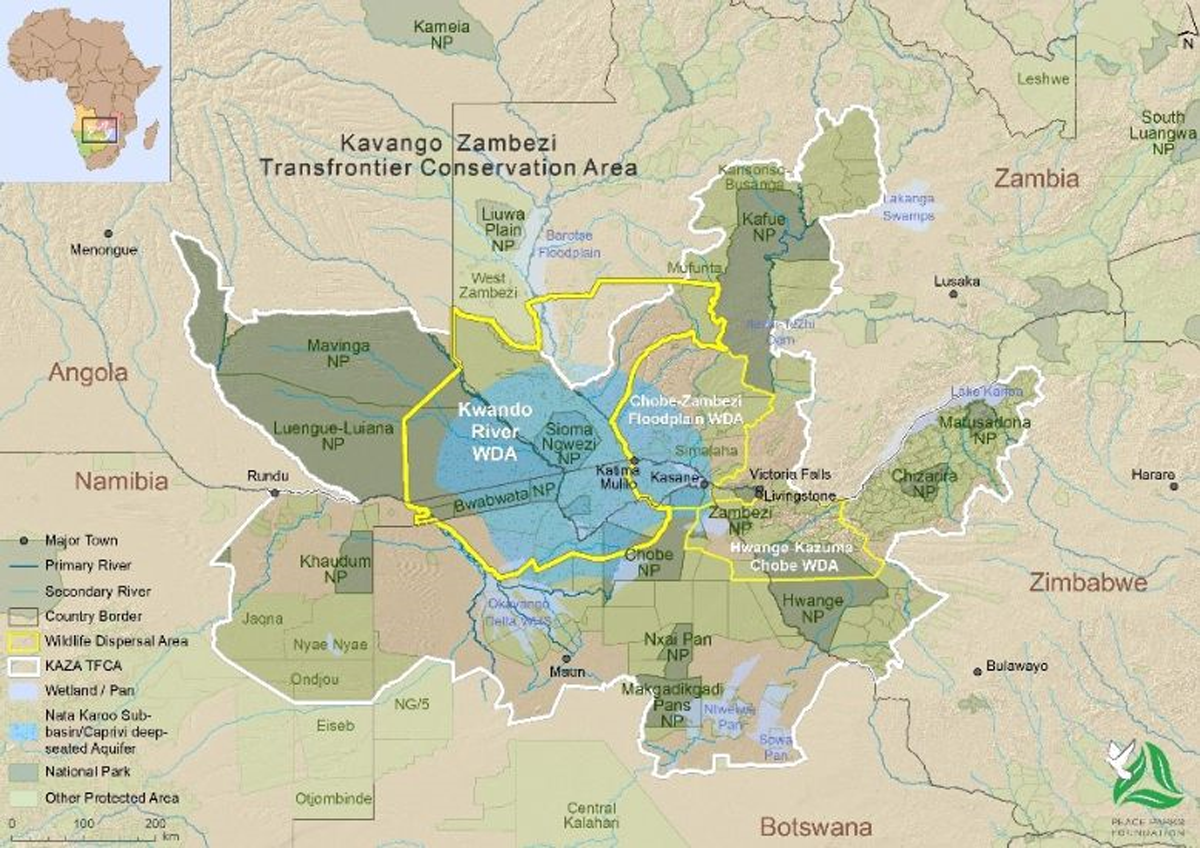

Figure 1

The KAZA TFCA and the Nata Karoo transboundary aquifer is marked in blue, whose exact delineation is uncertain (Source: The Peace Parks Foundation, Villholth et al., 2022).

Table 1

Summary of groundwater governance-related issues in the KAZA-TFCA.

| ISSUES | DESCRIPTIONS |

|---|---|

| Water scarcity | Southern Africa is classified as having moderate to severe water scarcity for more than half of the year (Mekonnen and Hoekstra, 2016) |

| Water quality/Pollution | Groundwater and surface water resources in the KAZA TFCA are polluted from various sources, including agriculture, industry, and sewage (Villholth et al., 2022). |

| Salinity | Widespread salinity in drinking water boreholes in both Zambia and Angola (Interviews with local communities). Salinity increases with the depth of boreholes, signifying a geogenic source of salinity in the study area (Magombeyi etal., 2022). |

| Borehole Drying | Shallow boreholes are often used to access groundwater for drinking, irrigation, and other purposes. However, shallow wells tend to dry up from August to November, and water becomes turbid during the rainy seasons from January to March (Magombeyi et al., 2022). |

| Lack of implementation strategies on conjunctive use of surface and groundwater | Ground and surface water management often fall under different agencies, leading to challenges in coordinating conjunctive use strategies. Transboundary guidance for conjunctive use of surface and groundwater resources in the SADC region is limited due to historical focus on surface water (Masemola & Pietersen, 2023; Sauramba, 2022). Local district councils are planning to augment and dilute high saline groundwater with surface water from local rivers (Interviews with local district council) |

| Climate change | Rising temperatures are expected to reduce groundwater recharge. Additionally, more extreme weather events, such as floods and droughts, are expected to become more common with climate change. Climate change is likely to exacerbate increasing water stress and water quality deterioration (Cumming, 2008). Local communities reported frequent flooding of the Kwando River, which causes damage to crops including damage from wildlife (hippopotamus). |

| Drought | KAZA TFCA and the southern Africa region are in general prone to drought, and these droughts are becoming more frequent and severe due to climate change. Droughts can significantly reduce groundwater recharge, leading to further depletion of aquifers (Perkins, 2020). |

| Lack of knowledge on the TBAs | The KAZA TFCA overlaps with five identified TBAs. At the same time, only two of them (the Eastern Kalahari Karoo Basin Aquifer System, and the Nata Karoo Sub-Basin Aquifer System) are presently associated with some level of knowledge although it still remains limited to understand its full extent and hydrogeological formation (Villholth et al., 2022). |

| Lack of data on and coordinated monitoring in TBAs. | Groundwater monitoring in the KAZA TFCA lacks transboundary harmonization across countries. Further, data collection and sharing are inadequate for transboundary groundwater management hampering informed decision-making and effective cooperation (Villholth et al., 2022). |

| Lack of natural resource transboundary coordination | Natural resource governance structures are fragmented across several institutions with no clear focus on groundwater (Villholth et al., 2022). |

| Human-wildlife conflicts | While there is a general co-existence of people and wildlife, some interactions may result in conflict, e.g., at water sources and crop fields. Most communities experience human-wildlife conflict, especially those located close to the Sioma Ngwezi National Park (Villholth et al., 2022). During the dry periods, communities rely on the Kwando River for drinking water, and they encounter conflict with wildlife when fetching water (Interviews with local communities). |

| Habitat fragmentation | Agricultural expansion and the erection of fences to protect the agricultural activities has fragmented wildlife habitats and isolated populations (Munthali et al., 2018; Nyambe, 2019). |

| Lack of joint knowledge and data sharing platform and protocol | The lack of a joint groundwater knowledge and data sharing platform in the transboundary aquifers is one of the obstacles to effective transboundary cooperation (Ebrahim et al., 2023). |

| Groundwater is not typically included in transboundary river basin governance frameworks | All five countries in the KAZA TFCA have well-developed frameworks for water resources management – national water legislation supported by national water policies. However, groundwater provisions are not uniformly developed to a similar level of detail. Priority in monitoring is given to surface water leading to limited understanding of groundwater/surface water interactions (Villholth et al., 2022). |

Table 2

Transboundary aquifers located in or overlapping with the KAZA TFCA (Source: Villholth et al., 2022).

| ID IN FIGURE 2 | NAME OF TBA | ID IN GLOBAL TBA MAP (IGRAC, 2022) | COUNTRIES SHARING THE TBA | SURFACE AREA (KM2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nata Karoo Sub-basin/Caprivi deep-seated Aquifer | AF14 | Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia | 90,982 |

| 2 | Northern Kalahari/Karoo Basin/Eiseb Graben Aquifer | AF10 | Botswana, Namibia | 12,336 |

| 3 | Eastern Kalahari Karoo Basin | AF12 | Botswana, Zimbabwe | 127,000 |

| 4 | Medium Zambesi Aquifer | AF16 | Zambia, Zimbabwe | 10,705 |

| 5 | Arangua Alluvial Aquifer | AF18 | Mozambique, Zambia | 21,235 |

Figure 2

Map of transboundary aquifers (blue) and transfrontier conservation areas (green) in SADC (Source: The Peace Parks Foundation, Villholth et al., 2022).

Figure 3

Multi-layered groundwater governance landscape in the KAZA TFCA.