Introduction

The commons, traditionally represented as shared resources managed sustainably by a community (Ostrom, 1990; van Laerhoven and Ostrom 2007), have become synonymous with transformative politics in times of ecological and social crisis, in their call for collective forms of governance alternative to market and state (Caffentzis and Federici, 2014; De Angelis and Harvie, 2014; Bollier and Helfrich, 2014). Critical commons scholars have further complexified the relationship of the commons vis-a-vis market and state by unpacking power tensions that exist in the spaces where these governance modes meet (Clement, 2013; Dell’Angelo et al., 2017; Nieto-Romero et al., 2019; Velicu and Garcí́a-López, 2018). Commoning – the act of a community reproducing the commons (Linebaugh, 2009) – has been presented as a form of resistance to a logic of commodification, and one that can be socially reproduced within thresholds facilitated by reclaiming public control, even in complex urban terrains (i.e through processes of remunicipalisation and public-commons partnerships, see Russell, 2019; and Thompson, 2021). Particularly in terms of an essential resource such as water, this implies blurring the line between public and commons, where government must first intervene to de-privatise its management, and further to this, enable water recommoning processes under a public framework. To recommon water, in this sense, transcends ownership and focuses on the co-production of politics of water in the city in common, and for the common (Geagea et al., 2023).

A persistent concern for commons scholars is to better understand what sustains commoning, particularly in urban terrains where such experiments are under ongoing neoliberal pressures. Considering limited empirical research that weaves insights from social movements with the theory of the commons, and the heavier emphasis on the ‘robustness of institutional design’ in the creation and maintenance of commons (Villamayor-Tomas and García-López, 2021), the day-to-day behavioural coordination and disciplining (micro-politics) are often overlooked. As such, a dialogue between commons and feminist literature becomes pertinent, and builds on feminist scholars’ call for integrating power relationships in the study of the commons (Clement et al., 2019). A feminist lens focuses our attention on the practices of how people participate in forms of social reproduction – the labour involved in the production and maintenance of life and community on a daily basis, which is often gendered (Federici, 2019) and consequently, with “disembodied constructions of the commons, the collective and the community” (Clement et. al, 2019: 2). As such, the focus of this paper is on the risks of disembodied constructions of the commons. These risks are captured through concerns from the ‘lived experiences’ of activists in a water struggle, as an entry point to study the (de)construction of a commons-oriented project.

Centering the feminist notion of embodiment in commoning, this paper presents an invitation to further expand on, and complexify, a theory of ‘embodied commons’. Doing so supports to challenge patriarchal approaches to participatory mechanisms in commoning projects, as well as forms of coopting the notion of ‘commons’ as an empty signifier, without enabling commoning practices. We employ a definition of embodied commons as the recognition of the corporeal, relational, and participatory concerns of the community that is physically reproducing the commons. Particularly in the context of building water commons, this paper invites paying attention to invisibilised knowledge(s), bodies, and practices in recommoning processes. Challenging the notion that institutions are ‘bodiless’ (see Boltanski, 2013), we also ask: how can we construct embodied institutions for governing water as a commons? To this end, we study an empirical case of the institutional recognition of water as a commons in Naples, Italy.

Growing dissent against commodifying water under a profit logic (starting from 1994 in Italy), resulted in the popular Italian referendum for public water held in 2011 (Marotta, 2016, 2019). With a majority vote against the privatisation of water, citizens linked the protection of water to broader democratic values, and to notions of commons (Bieler, 2021; Carrozza and Fantini, 2016; Fantini, 2012; Fattori, 2013). The results of the referendum were legally binding. Naples, however, was the first and only large city to ‘remunicipalise’ its water utility and align its water governance with a commons discourse (Bieler, 2015, 2021; Bianchi, 2022). More than a decade later, the commons-branded water governance model is found to still lack mechanisms for commoning. Our main results highlight the tensions that activists identified as the causes for Naples being an “incomplete water commons project”, one disembodied on several levels as we will argue. We focus on the transition from movement mobilisation to administrative institutionalisation of participatory mechanisms in the new Neapolitan water utility ‘ABC – Aqua Bene Comune’ (Water as a Commons) established in 2013, as the outcome. Our analytical framework investigates the types of knowledge(s) included/excluded in the process, gendered experiences, participation structures in the new governance model, and lastly, we bring into perspective external pressures under neoliberal technocracy to fail the Naples experiment.

The paper is organised in five key parts: first we frame the theoretical lens followed by an explanation of the methodological approach. The next part situates the case study of Naples in a context of water privatisation and market-oriented laws in Italy. The sections that follow outline results and a discussion grounded in the ‘lived experiences’ of the interviewed water activists and actors, underpinned by a feminist political ecology lens on embodied commons. The unique contribution of this research is its call for commons-oriented projects that better incorporate the embodied knowledge(s), experience and practices of activists who are necessary to the sustainability and propagation of a commons project.

Embodiment in Constructing the Commons

The notion of embodiment has recently regained attention in the study of the commons from a feminist lens (Clement et al., 2019; Mandalaki and Fotaki, 2020). However, the connection of embodiment to commons/commoning remains understudied (Mandalaki and Fotaki, 2020), with some exceptions (for example see Harris, 2015; Sultana, 2011). The theoretical contribution of this paper is to open a discussion around the importance of constructing embodied commons, paying particular attention to invisibilised knowledge(s), bodies and experiences in recommoning processes. We employ a definition of embodied commons as the recognition of the situated knowledge(s), the corporeal and relational experiences, and the participatory concerns of the community that is reproducing the commons. This definition builds on the concepts put forward by Mandalaki and Fotaki (2020: 746) on an embodied relational ethics of the commons, where ‘corporeal vulnerabilities’ and ‘relationality’ are the basis for social actors to reproduce their resource systems and communities.

Velicu and Garcia-Lopez (2018: 3) similarly argue the commons is a ‘relational politics’ and not only the technical management of resources. Particularly, from a political ecology lens, water services are seen as a deeply political – not simply technical – struggle that is negotiated and contested (Swyngedouw, 2018) where water is domesticated and commodified (Kaika, 2015). Thus the ‘relational’ dimension of water governance requires weaving theories of power into its analysis. For some FPE scholars, commoning creates collective subjects who exercise their power, creating socionatural inclusions and exclusions through a set of practices and relations (Nightingale, 2019, Singh 2017). A feminist lens, as such, adds value to viewing transformations of the commons by exposing “issues of inequality, power and privilege”, while foregrounding relational (including gendered and intersectional) experiences (Clement et al, 2019; Elmhirst, 2011). While FPE approaches have been criticized for their heavy emphasis on the biophysical resource (Sato and Alarcón, 2019: 40), in this paper, we lean on feminist frameworks to develop an analytical lens of an embodied commons that includes the embodiment of knowledge(s), lived gendered experiences, and commoning practices that respond to real needs (see Table 1). While focusing on the personal and relational, this ‘embodied commons’ lens also incorporates the rather structural tendencies of the broader social and economic context within which commons projects are embedded.

Table 1

Embodied commons conceptual framework (authors’ own).

| FORMS OF EMBODIMENT IN THE COMMONS | EXPLANATION |

|---|---|

| Embodied knowledge(s) | Situated knowledge(s) (Haraway, 1988) on the commons capture a form of embodiment. Feminist geographers have long challenged practices of knowledge created as disembodied and objective, by focusing on the link between knowledge and the body (Longhurst 1995; Thien 2005). This idea of embodiment strongly considers situated knowledge(s) as entanglements between aspects of identity, territory, and physical bodies that produce different ways of knowing (see Federici, 2019; Haraway 1988; Mies, 2014; Rocheleauet al., 1996). Similarly, in problematising risks of a ‘disembodied’ knowledge on the commons, FPE scholars call for “experiencing and learning from communities’ responses to environmental change in a participatory co-production of knowledge” (Clement et. al, 2019: 5), rather than reifying technical or “expert” knowledge. |

| Embodied experiences | Embodied experiences contain the corporeal and emotional dimensions, as lived through the gendered (and racialised ed.) body (Grosz, 1994). For instance, a concept like cuerpo-territorio, a feminist method from Latin America, emphasises embodied experiences of women in relation to their land and territory (Zaragocin and Caretta, 2021: 1507). Feminist political ecologists have connected the body to water in particular. Sultana (2011) and Harris (2015) connect contaminated water to experiences of emotional struggle. In this context, acknowledging embodied experiences can increase community-relational support for tackling resource challenges (Clement et al., 2019). Emphasising the gendered (and racial, class, age etc.) differences in lived physical experiences and how they impact the creation of the commons or manifest in commoning projects is critical when disentangling links between power, identity, a resource and the body (see Mandalaki and Fotaki, 2020; Sultana, 2011; Harris, 2015; Zaragocin and Caretta, 2021). |

| Embodied practices | Practices of inclusion/exclusion are often shaped and demarcated by institutions, understood as agreed to rules, norms and strategies (Crawford and Ostrom, 1995). Boltanski (2013: 54) speaks of ‘bodiless institutions’, claimed to be ‘timeless’ and ‘disembodied’ and yet that can only be created and defended by their spokespersons – actors who are often backed by power relations. Thus one can argue institutions are always embodied – the key question is ‘whose bodies’ are they representing? In the construction of the commons, it is therefore important that these institutions and rules, particularly around practices of participation and access to a resource, be open to co-design, critique and adjustment by those who are directly implicated by them. This is linked to decisions on how to participate in a resource’s governance structure, and the day-to-day collective ‘taking care’ practices (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2017). Such a lens can improve our understanding of the tensions that exist within commons-oriented projects that fall short of including institutions for commoning (see also Fournier, 2013; Gutierrez-Aguilar, 2017). Paying attention to structural disembodiment also points to the pitfalls of the role of public administrations in facilitating institutions (and laws) that are not ‘bodiless’ and ‘timeless’, while asking questions around ‘whose bodies’ are being invisibilised (see as example Kaika and Ruggiero, 2016; and García Lamarca and Kaika, 2016). |

Facets identified in Table 1 (below) are not exhaustive but include what has been covered in feminist literature. Additionally, while divided in this framework, they are not meant to be separated from one another due to their interdependence. From this lens, and building on the empirical results, we call for rethinking water governance (and governance of the commons at large) by looking at dimensions of dis/embodiment, through the recognition of situated knowledge(s), including lived and gendered experiences, and institutions that permit equitable access to decision making and the resource – as all shaping and sustaining (or not) a commons project.

Methodology

This paper employs a mixed qualitative methods approach, drawing on information collected from interviews, archival research, and grey literature, for conducting a case study analysis. The analysis is informed by a collaboration between the main author, a water governance scholar situated in a research institute in northern Europe, and co-author situated in a research institute in Naples; the latter with embodied experience as an activist in the Neapolitan urban commons movement, and in a ‘Feministisation of Politics’ collective within the European Municipalist Network.

The selection of the case study of Naples is founded on Flyvbjerg’s (2006) ‘extreme’ case criteria, where the outcomes of the case are considered to be unique. Naples’ remunicipalisation process outcomes are ones not found in any other Italian city. It is the only large city in Italy to date that has implemented the results of the referendum of 2011 for protecting water from privatisation laws in a way that recognises water as a ‘common good’. It has turned its water utility into a special company structure that is a non-profit model, and includes a participatory model in its statutes.

While the anti-privatisation and water movements in Naples date back to 2003, the rationale for choice of timeline to specifically focus on post-2008 events is because this research is particularly interested in the remunicipalisation wave that took place after the financial crisis and a series of austerity measures. While we recognise it is important to provide a historical account of the movement’s past, we focus on the events that took place in the process of water remunicipalisation starting around 2011.

A case study analysis is conducted with data collected by the first author through a set of 26 in-depth, semi-structured interviews over the duration of one year between June 2021 and August 2022, at times with follow-up interviews. These were conducted both online and in-person, with a fieldwork period of two months in Naples in 2022. The second author is situated in Naples, and embedded in its urban commons movement.

The majority of the 26 interviews (17 out of 26) are with water activists; 14 of these being from Naples’ water movement (past and current), and 3 interviews are with activists from the larger Italian Water Movement. Interviews were also conducted with 2 key public officials from the water utility; with 2 ex-politicians, namely Naples’ former Mayor and Vice-Mayor, 2 local artists and architects, and 3 experts (see list of interviewees in supplementary material). Nine of the 26 interviewees were female, while the remaining 17 were male.

In addition to interviews, archival material supported contextualising the broader legal frameworks in which Naples is embedded. Further screening of academic and grey literature from news articles and the water movement’s published documents were used for triangulation. Interviews were coded in a grounded approach, informed by general themes shaped by the research question of this study. Considering Lijphart (1971: 692) argues that a deviant case study can offer ‘great theoretical value’, the theory development both informed, and was iteratively informed by the results.

Case Study Background

Existing literature on Naples emphasise the procedural and technical transformations of Naples’ old water utility (ARIN SpA) into the new special company (Acqua Bene Comune – ABC), from the period 2011 until present (Agovino et al., 2021; Landriani et al., 2019; Lucarelli, 2011; Marotta 2019; Turri 2022). Few scholars have investigated this transformation from a social movement lens, recognising the lived experiences of actors who played a key role in reaching political buy-in and a favourable context for Naples’ water governance transformation (see Bianchi, 2022; Bieler, 2021; D’Alisa, 2010). The case study section situates Naples in the larger pro-privatisation economic and legal context, as highly relevant, considering this context both influences the motivations for Neapolitans to transform their water governance set-up, but also delimits this very experiment as an anomaly.

Growing resistance to a pro-privatisation wave in Italy

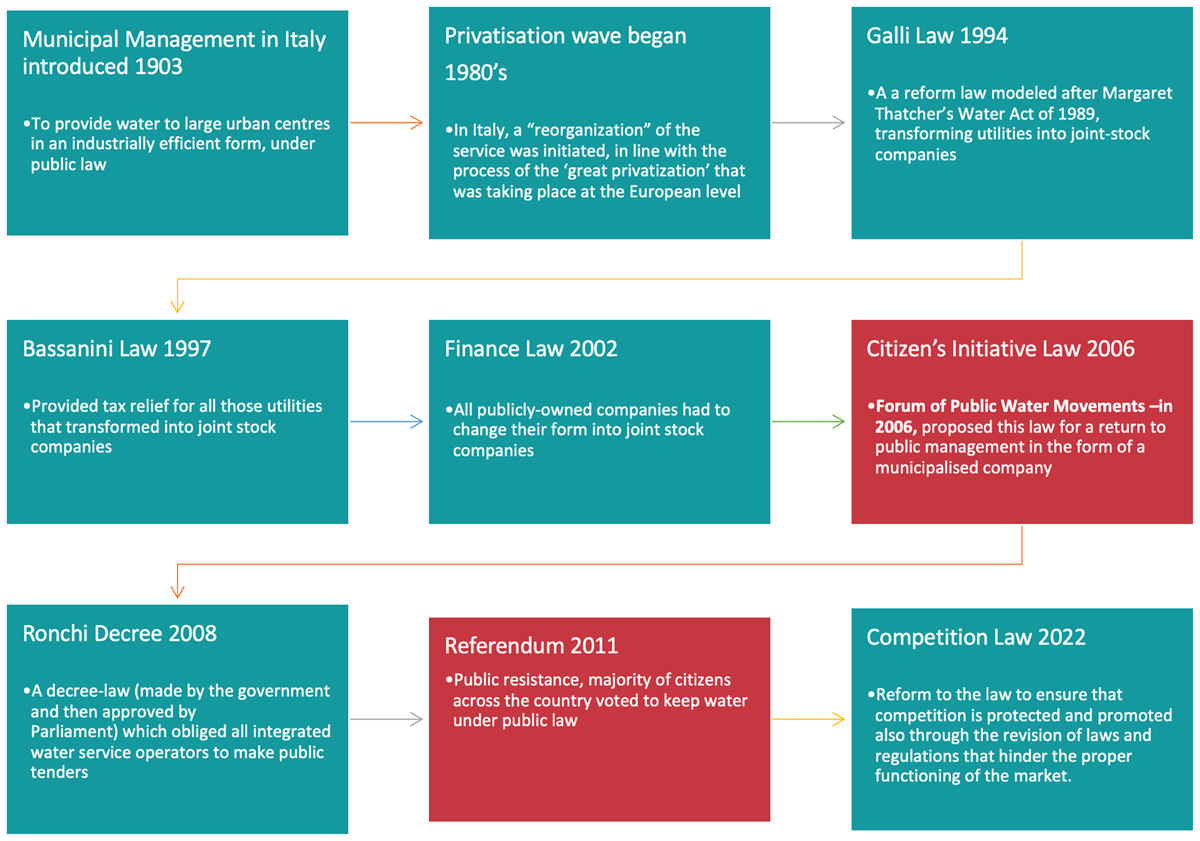

Italian laws implemented a steadfast project of privatisation and financialization of water services starting in the 90’s with the introduction of the Galli Law (36/1994) – a neoliberal provision that transformed water utilities into joint stock companies (see Figure 1), motivated within a European Union framework on financial policies. In response to this agenda, water movements rose in resistance under the alter-globalisation movement, emphasising water’s crucial role in sustaining life.1

Figure 1

Sequence of privatisation laws introduced by the Italian government between 1903 and 2022 (authors’ elaboration).

In 2006, the Italian Forum of Water Movements connected these struggles to a plurality of local “water committees” across the country fighting against the privatisation of water. ‘Commons’ entered the legal-institutional debate in 2007; the so-called Rodotà Commission effectively connected commons to fundamental rights, as a legal premise for a significant political discourse which was adopted by the water movement (Lucarelli, 2007, concerning commons and participatory management, D’Alisa, 2007). A Popular Initiative Law in 2006 was proposed to reform the water sector under public management law, with more than 400,000 citizens’ signatures. It was presented in Parliament in July 2007 (see Bersani, 2011 and Fantini, 2012), for which parliamentary discussion is still pending to date.

Despite movement demands, the Ronchi Decree was introduced in 2008 as a ‘seal-the-deal’ on privatisation as it forced municipal companies to compete under market criteria, and set a deadline to sell shares owned by local authorities (Massarutto, 2010 referenced in Fantini, 2012). Beyond the non-deficit obligations, pressure on municipalities to generate profits encouraged them to sell shares of water companies to large private investors – where there was a ready market (Kovalyova and Jewkes, 2010). This in turn triggered the strongest popular resistance that culminated into the 2011 referendum on public water, written and promoted by the assemblies of water movements under the Italian Forum for Water Movements.

The rising tide in Naples

Situated within this larger socio-political context, Naples is known for its complicated politics and challenging economic and social conditions which have given birth to a robust network of social movements. Neapolitan activists were involved in the anti-privatisation mobilisations that began in 2003, about ten years after the so-called Galli Law (36/1994). This law had paved the way for transforming the public water utility in Naples into a joint-stock company ARIN SpA, the shares of which could be sold. Other local resistances involved opposing the tender process in 2004 for a joint-stock company that would be in charge of providing the service in the territory of Naples-Volturno (covering a part of the metropolitan area around Naples and Caserta) (Marotta, 2019). While this tender was successfully opposed by water movements, it did not result in adopting full public management of the water service (D’Alisa 2010).

The Naples Committee for Public Water was created around the same year (2004), representing a diverse and heterogeneous coalition of local actors, animated since its beginning by different tensions – in a dialectic dialogue – concerning the attitude to relate and negotiate with government administration (D’Alisa 2010). This is because the movement ultimately found political support around 2011. The 2011 referendum, coupled with a wider discontent against austerity measures and mistrust towards traditional political representation resulted in a wave of municipalist politics rooted in campaigns around the waste and ecological crisis, water and urban commons, and the debt crisis (Pinto et. al, 2022). This fostered the rise of a ‘citizen-led party’ (lista civica). Namely, de Magistris’ lista civica won and attempted to reach what was considered an “exceptional convergence of movements and institutions” (Interviewee 23). De Magistris served as mayor for the next 10 years (until September 2021). While he adopted the movements’ commons discourse, and under his administration Naples successfully ‘remunicipalised’ its water – his role in coopting and institutionalising the ‘commons’ has been a controversial topic for many activists in the movement as will be discussed below.

Naples’ Aqua Bene Comune (ABC) – ‘Water as a Commons’ project

The city of Naples in the period post 2011 was perceived as a vanguard (and later an exception in Italy) in its remunicipalisation, to protect water from privatisation, and to mobilise a commons discourse for its governance. Local lawyers helped the city to adopt a provision (ex Article 114 of the Legislative Decree No 267 of 18 August 2000 – Code of local entities) that shifted their water utility’s legal model from a joint-stock company to an “Azienda Speciale” (special company). Under this model, the old public joint-stock utility (ARIN SpA) was turned into a 100% publicly owned and non-profit company in 2013. Under a discourse of commons, the new company was branded as Acqua Bene Comune (ABC) Napoli – ‘Water as a Commons Naples’, which was established in April 2013 as the newly named public company, managing water services for 1.5 million people.

Unlike its predecessor, the ABC model prohibits selling shares to private actors and reinvests the surplus generated back into the utility. This has resulted in water bills being lower than those of private utilities in the region of Campania, while maintaining quality standards (Turri, 2022). Moreover, this new structure introduced a President and board who serve by appointment from the mayor. Most importantly, the new water utility’s statutes include an aim to “enhance the nature of water as a commons” (Bianchi, 2022). Civic participation was driven by a ‘commons-logic’ to include a Surveillance Committee that has functions of “consultation, control, information, listening, and debate” represented by 21 members from whom 5 are civil society members from registered environmental organisations (ABC Statutes, Chap 2, Art. 41).

Results: Naples’ Incomplete water commons project

While Naples gained its reputation as a vanguard in succeeding to remunicipalise its water utility in line with a commons discourse, the process of turning movement demands into administrative institutionalisation was highly contentious and divisive (D’Alisa 2010). Our results are interpreted through a framework that investigates four key factors of dis/embodiment and enclosures: (i) types of knowledge(s) and expertise included/excluded in the process, (ii) gendered experiences and power dynamics (iii) outcomes of participation structures in the institutionalised model, and ultimately (iv) external relations to this institutionalisation.

Enclosure of knowledge(s): Technocratisation of the water struggle

“Water is life, it was a cultural, moral, political statement on big issues… on life, politics, democracy… all this was reduced to this very technical point.” (Interviewee 39)

The water movement in Naples is not ideologically homogeneous. It is composed of water activists that celebrated a diversity of ideologies in the lead-up to the 2011 referendum. The different positions and situated knowledge(s) found a common interest in recognizing water as “a symbolic battle against all privatisation” and the local water committee had “created this democratic system, of holding assemblies where consensus – and not majority voting – prevailed” (Interviewee 33).

As mentioned earlier, the anti-privatisation and water mobilisations had started around 2003 in Naples, where singular entities merged officially in 2004 into the Naples Committee for Public Water, while maintaining heterogeneity and at times different political demands, which heavily conditioned that the movement later collapsed in its diversity (D’Alisa 2010). Mobilisations continued locally beyond the success of 2011 referendum, as it was declared that “for the Neapolitan citizens and the committees that promoted the referendums, [the success of the referendum was] just the beginning; the challenge will be to guarantee real and substantial participation in the management of the Integrated Water Service by the community of citizens and workers” (Comitato Acqua Pubblica, 2011). The emphasis on the ‘real and substantial’ participation of the community and workers in the management of the water service meant the integration of a diversity of knowledges on water, from activists, users and technicians.

However, the public administration needed support in implementing a commons framework to Naples’ water governance since there was no precedent for turning a joint-stock water company into a non-profit public company (see Micciarelli, 2021). This led to the centralisation of legal discussions which distanced the inclusion of some activists on the ground who held values and practices (forms of commoning) in line with deliberating in open assemblies (Interviewee 39, 48). This has been explained by D’Alisa (2010: 14–15) as a division between “civil society” – organisations and individuals that “recognize two types of authority: that of experts (those who know more than us) […] or worse, […] the authority of idols”; and “uncivil society”, which captures the radical vision of those who “want to share bread and not just ideas” in processes of social and political transformation.

The institutionalisation of water as a commons in Naples was thus enacted by experts without deliberating over it within the movement (Interviewee 33, 36, 40). Some activists in the water movement resisted those who posed as its ‘leaders’ and who agreed to the statutes of ABC without taking it back to the rest of the water committee: “whoever represented that committee did not decide for everyone” (Interviewee 33). Nor the fact that a national leader of the water movement, Ugo Mattei, was appointed by the mayor as president of the new utility ABC, as opposed to appointing a ‘local expert’ (Interviewee 48).

In this context, the centralisation of technical expertise enhanced the visibility and decision-making power of certain people (predominantly white men), by legitimising specialised knowledge of actors from established political, research, and cultural institutions. In turn it invisibilised the different types of expertise and knowledge(s) embedded in the movement from a decade of mobilising around anti-privatisation and water issues.This knowledge includes the elaboration of the 2011 referendum questions, and the 2006 Popular Initiative Law collectively by broad assemblies of the water movement. Even more, this technocratic2 shift watered down the radical political vision of the movement (Interviewee 39). An interviewee emphasised that the idea of a water commons cannot be built “without those who materially put their hands on [water] and can tell you where that water passes, where it is best to intervene, have [tacit] knowledge”, meaning the users and workers (Interviewee 33). In contrast, we interpret what happened in Naples as a technocratic turn, that not only divided the movement but also diminished its practices of commoning.

Enclosure of experiences: Invisibilized bodies

“There was a patriarchal way of doing politics, a way determined by the fact that they [the leaders] were male…” (Interviewee 31)

A gendered lens highlights the predominance of a ‘culture of masculinity’ (Shrestha et al., 2019) that is performed and reproduced within the process of building the water commons project in Naples. Male figureheads (white cisgender3 male, with a structural advantage in religious/research/political institutions) assumed leadership roles – to varying degrees – and became more visible in the techno-legal water governance transformation, including receiving credit for its success (Interviewee 31).

It is worth noting that in conducting the interviews we had a difficult time reaching women water activists in Naples, due to consistently being referred to male actors. It later became clear that women played a major role in the success of the 2011 referendum (confirmed by Interviewees 31, 33, 36, 40, 41, 46). As described by D’Alisa (2010: 15), one part of the movement “can be associated with the feminist majority that has energized the coordination [of the committee]. […] This group, with which I identify myself, is very heterogeneous, both from the generational point of view and from the socio-cultural point of view, with an equal weight of gender”. A male activist explains however, that while women were very involved in taking care of practical matters, “it was usually men who were sent” to represent a territorial water committee (Interviewee 33). Another male activist confirms that “the women who were instrumental in the water and waste movements were doing all the caring work and the men were in leadership” (Interviewee 36).

A female activist who left the Naples Committee for Public Water relates underrepresentation of women in the public face of the movement to a ‘patriarchal way of doing politics’ and a ‘toxic masculine’ way of approaching discussions (Interviewee 31). She links this to the fact that the ‘leaders’ did not open up space for inclusive participation: “they thought it was necessary to eliminate discussions, for the ‘good’ of the movement”, which led to disagreement being seen as a lack of support for the struggle (Interviewee 31). This erasure of democratic deliberative practices even within the movement, by “idols” and “experts” could explain what may have weakened the movement’s demands for shaping commoning into the new water governance model. Some of the women’s stories explain that they shifted their participation to other social movements such as that on waste or urban commons. In these movements they encountered a more ‘horizontal approach’, including bringing forward conversations around the ‘de-patriarchalisation’ of the relational aspects of commoning work (Interviewee 31, 37, 46).

A different account was presented, however, by an activist who has been involved for nearly 20 years (since 2004) with various representation roles and is one of a couple of key women still active in Naples’ Committee for Public Water. She differs in her perspective that representation is an issue within the activist water committee (Interviewee 45). While she viewed the water movement as an equal terrain, with mechanisms for co-spokespersonship, the reality remains that the recognised ‘leader’ of the committee continues to be a famous priest figure. Yet for her the issue remains with Italian politicians who are dismissing the water movement as:

a women’s thing…women who make trouble, but don’t understand what the big problems of the reality of [water] management are. It is in that relationship that being women and gender becomes an issue. Because if, in front of [the vice president of the region], there had been three men in suits, the kind of interlocution would have been different (Interviewee 45).

Ultimately she affirms that “water is a women’s issue because it has to do with care, with the transmission of life, with the maintenance of life. […] We always had so many women in the demonstrations, even women precisely of heterogeneous ages coming down” (Interviewee 45).

The gender analysis highlights, then, two levels of gendered tensions in constructing a water commoning project: the first being a reproduction of patriarchal tendencies within an ideologically heterogenous movement, where women are overshadowed by male “expert” and “idol” figures (D’Alisa, 2010); and the second being a larger structural patriarchy that labels and dismisses a water commons struggle as a ‘woman’s thing’. This contradiction in experiences is partially explained by feminist theories underlining the links between ‘genderisation’ (and now racialisation) and invisibilisation of care work (Cox and Federici, 1976; Fraser, 2016).

Additionally in terms of age, it was pointed out that what is most lacking is generational turnover within the movement: “We are all people who have been in the movement for some 20 years. The young people, while familiar with the water issue, however, are not internal to the movement except to a small extent” (Interviewee 45). These facets reduce the embodied representation of intersectionality of gender, age, race and class diversity in a heterogenous group that includes queer, non-binary, or those at the intersections of other identities, races, and social status who are fighting the same fight to protect water, but whose voices (and bodies) are not visibly represented.

Enclosure of practices of participation: Representation vs. commoning

“The problem is that [ABC] is a model that was born with participation, but participation had its legs cut off from the beginning. […] Participation is born where there is a movement and you win it from below. If you create it, but there is nothing on the ground, it becomes a problem.” (Interviewee 31)

To discuss water as commons instead of a traditional public management, it is necessary to investigate the process that happened between transitioning from movement practices and vision to the creation of ABC’s participatory model – that particular space of ‘negotiation and contestation’ in between.

In the case of Naples, after the 2011 referendum, and especially after the incoming mayor de Magistris announced the remunicipalisation of water, the activists in local water committees began separating (Interviewee 33). Some believed the goal was achieved and no longer participated. Others proposed collaborating with the new administration and entering the governance structure of ABC to protect civic participation. Others strongly opposed participation on the grounds set by the administration, because selecting representatives indicated reducing participation to ‘delegation’ (Interviewee 33, 44). Delegation countered the water movement’s tradition to “maintain an inclusiveness of all subjects and give everyone the same dignity to speak, give their opinion in the assembly and reach a maximum common denominator” (Interviewee 33). This praxis was questioned by institutional interactions since the beginning and eliminated in the new ABC participation model. The day-to-day practices of decision-making in ‘informal’ (open) spaces were replaced and ignored by ‘formal’ spaces. The legitimacy of the formal is determined by the administration and hosted in the highly securitized, guarded and exclusive spaces of the water utility. Thus, the question of “who participates, where, and how, and what are the respective roles and interests of the participating actors” delimit the politics behind the decision-making process (Kaika, 2003: 304).

Considering this remunicipalisation aimed at institutionalising water as a commons, the outcome of the ABC governance model lacks channels for commoning. Within ABC’s Statutes, proposed in 2012, a Surveillance Committee (SC) is described to be the official institutional vehicle for the “participation of citizens in the governance of water as a common good” (ABC Statutes, preamble). With a composition of 21 members, this SC still did not consider the inclusion of the diversity of local water activists (Bianchi, 2022). Moreover, the total of 5 board positions reserve 2 spots for civil society organisations which in the last cycle, appointed by the De Magistris administration were MareVivo and the World Wildlife Fund (ABC Statutes, Chapter 2, Art. 41; Interviewee 34). A series of presidents and commissioners were tasked with figuring out ABC’s civic participatory component (see Bianchi, 2022). Growing dissatisfaction with this model was not resolved when, in 2016, the board resigned due to resistance to opening up the board meetings to citizens. The commissioner at the time ratified the ‘civic council’ – an open assembly from which movement ‘delegates’ can be sent to the board meetings (Interviewee 25). Indeed, some activists claim even this version “was not real participation” because groups were still “called upon” to participate, and where disagreement was turned into a “timed and limited intervention” rather than a deliberation (Interviewee 31).

Interestingly, a member of the previous government administration seems to be aware that “the way a community interprets the commons may be different from the way an administration interprets it” (Interviewee 23). He further explains that the model of ABC, as a special company with full public control, is an advancement on the old utility’s joint-stock model, because it includes various channels for participation processes that did not exist before. For instance, by regulation, the ‘community’ can activate councils and actively decide on how to invest and reinvest profits in water infrastructure, or to call abrogative referendums that can prevent the ABC administration from acting without discussion with the community (Interviewee 23). This leads to the question of who is included and excluded in this notion of ‘community’ and ‘councils’. In practice, the interviewee acknowledged that these councils “can turn into micro-groups of technicians” (Interviewee 23). In contrast, an activist defines the commons as: “a concept of struggle, and commoning can maintain alive the process of involvement” (Interviewee 48).

While theoretically promising, in reality, the activists from the Naples Committee for Public Water who became involved in the ABC governance structure explain they faced several challenges (Interviewee 45). Firstly, since ABC’s leadership are appointed by the mayor, members felt a pressure to take a position of alignment, placing their resistance in a compromised position (Interviewee 45). Additionally, they explained that directly managing a company with a complex budget requires “technical and managerial skills that the [activist water] committees do not have”, where “they should rather have a policy and control function” (Interviewee 45). The president of ABC acknowledges it can be debilitating for activists to ‘perform’ inside bureaucracy (Interviewee 26). Evidently this institutionalised format of ‘participation’ has not satisfied the appetite for deliberative democracy of community activists, nor has it provided a space for commoning.

External pressures of enclosure on Naples: from vanguard to anomaly

“Look it can be done, because Naples did it.” (Interviewee 43)

Naples is considered by water committees around Italy as the model of reference for implementing a fully public and, even more, commons-oriented governance structure (Interviewee 40, 41, 43). The novel institutions created by Naples facilitated dynamics of counter-powers to resist the general politics and market-logic of the national government on matters of commons (Pinto et. al, 2022). Consequently, the Neapolitan administration faced displacement, seen as a problematic ‘anomaly’ in the region (Interviewee 23).

Particularly in 2014, the national government introduced a bill for creating water authorities specialized for each region (art. 7 of Legislative Decree 133/2014). In Campania, the Ente Idrico Campano (EIC) was formed, which brought together seven district areas, forming a single entity to manage public water and plan for investments (Ente Idrico Campano, 2023). This became administratively problematic for Naples because the City has had water investment proposals rejected due to ABC’s ‘different’ legal-administrative set-up compared to the other municipalities in the EIC. As such it is being isolated, in turn pushing it to return to the model of joint-stock company (Interviewee 23).

After the COVID pandemic, new risks emerged with the implementation of the Next Generation EU regulations, namely through the Law on Competition (l. 118/2022, art. 8), requiring a strong justification for the decision of in-house management of public services – including water. Following the pressures of public opinion, the final version of the law dilutes this requirement, but the subsequent decrees still impose the consideration of financial spending (D.lgs 201/2022, art. 17).

A water activist describes this situation as paradoxical because Italy is the only country in Europe that had a referendum to protect water from private interests and yet Naples became the only city having implemented it (Interviewee 43). However, activists also point to the “war against ABC” by politicians in Italy, where central left and right parties agree on privatization (Interviewee 40 and 41). Despite dialogues over the commons in Naples, it is not the mainstream view of the current administration who are pro-privatisation (Interviewee 37).

Through a structural lens, there is a wider scenario of neoliberal technocracy that continues to enclose the Neapolitan water commons experiment, by limiting its influence and its access to funding; as such both disciplining it, and maintaining it as the anomaly.

Re-embodying Water as a Commons

A commons cannot be built without a community that cares for, and reproduces it (Mies, 2014). The authors warn against the commons becoming an ‘empty signifier’, and in line with Federici (2019: 102), warn about capital co-opting its “virtues”, and even discourse without founding it on the embodied experiences of the community. It becomes necessary then to expose the “contingent and ambivalent outcomes” (Clement et al, 2019: 7; Nightingale, 2019) and the “oppressions” and “straitjackets” (Esteva 2014: i147) of the commons, not to diminish it as an emancipatory form of governance, but in order to avoid unintentionally reproducing power and access inequalities in its construction (Sato and Alarcón, 2019). From this framing an ‘embodied commons’ theory helps build on the concept of a commons-oriented water governance model that is embodied by the people (activists and residents of a hydrosocial territory) who rally behind it, their physical bodies, and their relational links with water, with each other and with the new institutions that are set-up. How social actors can reproduce their resource systems and communities based on their collective concerns is a tension that keeps challenging the sustainability of commoning projects (Mandalaki & Fotaki, 2020). It is thus important to not reproduce the commons in disembodied forms from the material bodies of inhabitants who live in the territory.

In this sense, commons institutions should be designed in a way open to being transformed by the commoners to respond to their real embodied needs – with attention to whose bodies (and consequently knowledge(s) and experiences) are being invisibilised. Attempts have been made, for instance within the urban commons in Naples, to include politics of care for creating open and horizontal practices between institutions and residents, to reduce power hierarchy and inequality (Micciarelli 2021: 31).4

Moving from this theoretical stance, it is possible to consider some reflections towards a re-embodied water commons that can support future commoning experiments. The first reflection concerns the risks of enclosing knowledge to technocratic expertise, thus invisibilising the tacit knowledge of activists. Success of the Naples case in remunicipalising its water company (into a not-for-profit utility) is a powerful message that this type of privatisation resistance can be done at a complex city scale despite a national neoliberal agenda. However, creating a commons relates to enabling forms of commoning, through engaging situated knowledge(s) that are linked to “identity, power, location, and materiality” (Zaragocin and Caretta, 2021: 1505). It is necessary then to explore how in a commons-aligned project, knowledge can be collectively produced – and presented – in a way that is accessible to the community’s participation and protagonism, recognising and embedding the practical water expertise, emotions of movement actors and their tradition of praxis – ways of doing – such as gathering in open assemblies. This can shift the role of the ‘expert’ to involve the community. As in Funtowicz and Ravetz’ (1994) post-normal science that does not exclude “non-experts” and that accepts “as a scientific community the loss of its monopoly as an official expert”, knowledge can be socialised for policy decisions (D’Alisa, 2010: 15).

The second reflection concerns gender imbalances and patriarchal tendencies, invisibilising and marginalising certain bodies in the construction of a commons-oriented project. Such imbalances delimit who gains more access to decision-making spaces on a natural resource and its management, reproducing patterns that exclude – often women – from such positions of power. In fact, a criticism to institutional theory’s framing of ‘sameness, cooperation, and consensus’ as necessary for preserving a commons, is its neglect of the possibilities to reproduce ‘existing power relations and patterns of exclusion’, as forms of enclosure with ‘narcissistic, nationalistic, patriarchal, or racist overtones’ (Velicu and Garcia-Lopez, 2018: 5; see also Caffentzis and Federici, 2014). By paying active attention to such tendencies that are not merely about gender balance but also include recognising patriarchal tendencies, monitoring mechanisms can ensure embodied gendered experiences are fairly represented.

The urban commons activists may have learned from the mistakes of the water-commons experiment, employing a non-hegemonic approach by “starting to discuss the importance of the de-colonization and deconstruction of power” (Interviewee 46). This became their priority after the encounters with the feminist practice of Non Una di Meno.5 In turn, another activist explains that placing ‘care’ at the center helps to “erase the machista and sexist relationships within the movement” (Interviewee 36). Such a gendered lens, conversations, and work is deeply valuable to address gendered tensions in constructing commons-oriented projects. In the work on sustainable management of natural resources, Giambartolomei et al. (2023) offer insights on how professionals in the public sector can transform governance relations “through relational, integrative and caring forms of democratic governance” towards alternative ways of “doing and being together” through “‘lived’ and ‘owned’ institutions”. Similarly, the work of Dengler and Lang (2022) on the commonization of care argues from a feminist degrowth imaginary for the creation of “transformative caring commons” in socio-ecological provisioning.

The third reflection concerns the risk that public administrations instrumentalise and dilute participatory democracy tools. Water activists in Naples desired a civic-deliberative mechanism for decisions on water in their city but remained entrapped on the outside of the governance structure. It is therefore important to challenge the possibility of innovating on water institutions without changing the traditional – and often criticised – institutions of participatory democracy that can lead to the exclusion of certain actors, like frontline activists and marginalised residents. Here again, the work of feminist scholars as mentioned above invites those in public office to recognize their agency and power in being able to shape governance through experimenting with collective ways of doing and caring.

Finally, on a macro-political level, the persistence of austerity regimes and the revival of privatisation policies in the EU, even after the COVID pandemic, enact a form of neoliberal technocracy and institutional disembodiment, where water decisions are detached from basic needs and regulated according to dominant economic theories, protective of creditors’ interests rather than fundamental rights of citizens. The lens of embodiment, from a FPE perspective, allows to observe how patriarchal logics of micro- and macro-politics both reflect in one another, thus requiring an overall rethinking of political participation, in a way able to recenter movements and institutions around currently invisibilised and exploited bodies and their knowledges and practices.

Conclusion

Contesting the notion of the possibility to build commons without commoning merits investigating the micro and macro-politics of commons-oriented projects. An FPE lens helps to understand how commoning practices encompass the situated knowledge(s), lived experiences and practices of actors, in intimate and embodied relationships and institutions constituted between humans and the environment.

Results from the narratives of interviewed activists in Naples highlight that, while it is a case of a successful water remunicipalisation (marketed under a discourse of commons), it remains an incomplete water commons project. It is ‘incomplete’ in the sense that the commons logic that drove the legal-political and branding changes of the new water utility (‘Water as a Commons’), ended at the technical and administrative reformulation. Today, this water commons project is lacking a mechanism for commoning.

Creating commons-oriented water projects is necessary for emancipating residents and their relationship to water in urban environments from the grip of market and state, but it is important to ask: are these commons projects embodied enough? Commoning is a process of ongoing voicing of collective concerns, and reproduction of knowledge(s), experiences and practices that enable the design of institutions that are responsive to these embodied needs – in essence it needs a community to rally behind it. The relevance of an embodied water commons is that it can reflect people’s– including those marginalised and at the periphery– real concerns and immediate decisions if there is a water crisis or emergency.

Thus embodied commons are at lower risk of being either dismantled or coopted. For instance the risk with a pandemic, or a drought or flood, is that decisions under a public-private model tend to get made in the boardrooms of multinationals far removed from the situated needs of the people in a territory. At least in Naples’ case, the now fully public water utility is answerable to its citizens and to the municipality, both of which are channels of resident’s concerns. However, it is critical to investigate how administrative alignment with movements can transcend a mere commons discourse and can facilitate ‘caring’ assemblages as custodians of more embodied, locally-situated, and sustained water futures in cities.

Notes

[1] The first Manifesto for a World Water Contract was crafted in Lisbon in 1998 by a group of economists, including Riccardo Petrella and Rosario Lembo. The manifesto advocated for the recognition of the right to water, with a clear international connection to the World Social Forums, in Chiapas in 1994 and in Porto Alegre in 2002.

[2] Technocracy is defined as a ‘system of governance in which technically trained experts rule by virtue of their specialized knowledge and position in dominant political and economic institutions’ (Fischer, 1990: 17).

[4] See the work of the Feministisation of Politics collective: municipalisteurope.org/fop/.

Funding Information

The authors acknowledge funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Innovative Training Network NEWAVE – grant agreement no. 861509.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.