Introduction

“We suffer more often in imagination than in reality.” Seneca, Roman philospher (4 BC to 65 AD).

Originally prepared as a conference keynote address,1 this paper reflects on how images guide the way small-scale fisheries are governed. Images are the pictures, models, maps, or narratives used to mentally capture things that exist in the real world. They are what we read into and out of what we see. They are “like the circles that you find, in the windmills of your mind” – as Noel Harrison’s song text goes.2 None of these should be confused with the thing that is being portrayed. To put it like sociologist Erving Goffman (1974: 2), images are “the camera and not what it is the camera is taking a picture of.” Images, nevertheless, allow us to recognize what we observe. They help us to organize our experiences. They play, as Kant argued, a central element in our perception, as perception requires an image (cf. Matherne 2015). They turn an observable object or occurrence into something that we have an idea of already.

Images have consequences for what we do in the real world. They are what we communicate, as when we draw a map or tell a story, form an opinion, and convey a message. We use them to argue a case. They are integral to what J.L Austin (1955/1962) called “speech acts”. They also have a direct impact on reality when we act on them, as when “God created man in his own image” – and by that gave men the “dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth” (Genesis 1;26–27). And indeed, men have acted on this delegated authority, but dismally so.

Wen sociologists argue this point, they often refer to the so-called Thomas theorem, which states: “If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.” (Thomas and Thomas 1928: 571–572). This is because we act on our definitions, and by that confirms them. It is for this reason that images often turn into “self-fulfilling prophesies”, as the sociologist Robert Merton (1948) said, whose outcomes may be good or bad. For this and other reasons, governance theorists like Jan Kooiman (2003) argue that images should be made explicit and scrutinized as part of governance. They should not be taken for granted as true representations of the world but challenged and tested. It is always possible to look on things in different ways at various stages of the governance process as participants learn from experience.

With his famous “Tragedy of the Commons” article in Science (1968), Garrett Hardin left us with a narrative that has played a huge role in the way fisheries are governed all over the world. He did not talk specifically about fisheries but the parallel is clear. Not only does it offer a definition of “the fisherman’s problem” as McEvoy (1986) coined it, but also a recipe for how to solve it. Kooiman (2003: 20) observes: “His (Hardin, SJ) suggestions that humans are relatively short-sighted, non-communicative and profit-maximising beings have exerted substantial influence on management theory and practice and have provided an impetus towards privatisation of fishing rights.”

Maurstad (2000) argues that policies based on Hardin’s image may evolve into a self-fulfilling prophecy. Whatever fishers were to begin with, they develop into “calculating machines”, as Marcel Mauss (1954/2000: 74) coined it, because to survive under the new regime, they must. Nonetheless, fishers and fisheries governors must deal with the same issues that Hardin discussed, such as over-exploitation of natural resources and consequences of ecological devastation and human poverty, but they do not necessarily have to follow his recipe. Researchers have questioned whether the image of ’tragedy’ offers a good fit with the problems and opportunities that fishers and fisheries governors are facing in the real world.

My theme

Although I will have thoughts to offer on the Tragedy of the Commons, my concern in this text is more general. I will explore the relationship between images on the one hand and how we see and make sense of the world and what we in the next instance do with it, like in a fisheries governance context. I shall argue that there are alternative ways of looking at the fisheries commons, and that other images may be more appropriate. Fisheries governors must have a more playful attitude to image formation to trigger governance innovation and avoid failure. James March (1976: 77) posits that play is “an instrument of intelligence, not … a substitute” because it allows learning through experimentation. Governors should experiment in the small before they introduce grand reform schemes.

Images, and their instrumental functions, belong to what Kooiman (2003: 6) categorized as “meta-governance.” They are building blocks, an “imaginary governor” by framing institutions, agendas, and actions. Institutions, once in place, tend to safeguard their formative images, and by that reinforce each other (Unger 2004). By this they both assume a degree of stability. Images are both forerunner and offspring in the iterative governance process from which institutions emerge and function. They may change as governors learn from failures and successes.

What I have to say about images in the following draws heavily on sociological and philosophical discourse. The reader should, however, think of small-scale fisheries, which is what I did when I was composing this text. Not only do I think that our understanding of small-scale fisheries would gain from broadening the context and the perspective. I also believe that small-scale fisheries may provide insights for other sectors that are facing similar challenges. They are also a mine for theoretical reflection on the fundamental premises for governance itself, for how to think about the relationship between image formation, knowledge building, governance intervention and innovation.

Enlightenment

“Men are mightily govern’d by the imagination,” David Hume (1711–1776) said. Hume here engaged in a long tradition of thought, with Plato and his mentor Socrates as forerunners. The latter two considered imagination the weaker form of knowledge. This is especially the case when compared to knowledge built by rational thinking and empirical investigation. Images may be simplistic, ambiguous, and erratic, and certainly biased. They are nevertheless indispensable. If we want to create a different future for small-scale fisheries, one in which they are thriving, we must first imagine it. We must have an idea of what that future might entail to understand what we are aiming for and how to get there. To create it, we must imagine that another future is possible (Jentoft and Eide 2011).

We have images at the outset of the knowledge building process, and they often change during it. We begin with an idea of how the world works, but as we gain more experience, we may come to see things differently from what we did before. There is more to learn as new questions emerge. To be tested, hypotheses must first be discovered, but testing is also a discovery process (Nisbet 2001). Hardin’s image is first and foremost an eye-opener to something that is worth exploring.

Images become reservoirs of meaning and knowledge; they are tapped and refilled in an iterative process. They inspire new interpretations, investigation, and discovery. We may commence with Hardin’s image of the Tragedy of the Commons but end up with a more nuanced or completely different image, which may lead us to redirect governance efforts.

Aristotle warned that as images motivate and guide action, they can also lead us astray3 (De Anima iii 3, 428aa1–2).4 Images are not necessarily true representations of what they picture. “Imagination may be false,” he said. We are not always seeing what we believe we see. We may be like the captives in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave (in The Republic).5 Here, Plato asks us to “picture men in an underground cave-dwelling…” They are locked in a position where they cannot see the light from the fire behind them. The only thing they ever saw are the shadows on the wall, which make them believe that they are the real thing. With the allegory, Plato noted that our images are determined by the vantage point. If the captives were free to go outside the cave, they would see a different reality, the light from the sun. They would be ‘enlightened’.

The commons image

Hardin asks us to “picture a pasture open to all where each herdsman will try to keep as many cattle as possible on the commons.” It is not hard to draw such a picture in our mind, we can easily see it with our inner eye. Then, Hardin leads us to conclude that the outcome is given; “the inherent logic of the commons remorselessly generates tragedy” (Hardin 1968, p. 1244).

In his reasoning, it is rational for the individual herdsman to increase his herd, as he gets the full value of each new cattle whereas the costs due to the added pressure on the pasture is shared by all herdsmen. When every one of them thinks and act like this, the outcome is inevitable and devastating, just like in the ancient Greek theatrical plot. There is nothing to stop them. Eventually the grazing land will be ruined, everyone suffers, and poverty is predictable. The tragedy is not hard to imagine in real life, like in fisheries. Without restrictions, fishers will bring on their own calamity by fishing more than fish stocks can sustain.

Hardin’s ‘tragedy’ explains the need for restrictions, because “freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.” Therefore, the situation calls for limitations of that freedom, and it must come from the outside because individuals will be inclined to freeride. In the classical tragedy performance a figure is lowered down onto the theatre stage and solves the problem for them. This is the Deus ex machina, the “God in the machinery”, which in Hardin’s allegory is the state.6

Hardin’s image fits what Jean-Paul Sartre (1964) coined “counter-finality”, which he illustrated by peasants in China doing what Hardin’s herdsmen might have done; cutting trees to create more pasture but which led to deforestation and soil erosion. By solving one problem, they created another, equally as devastating. Hardin’s and Sartre’s narratives legitimize external intervention. Their image provides an answer to a problem that it defines itself. But what they ask us to picture may nonetheless be shadows on the cave wall.

Images as ideal types

Like Plato, Hardin makes an analytical point. He asks us to envisage commoners free of restrictions acting on their own individual economic calculus. If we accept this premise, we must also agree with the logic and the prospect. It is in a sense, a mathematical statement, like 2 plus 2 is 4. This was, is, and will always be true, with the power of logic derived from first principles. It cannot be falsified by empirical evidence. It is, as Gregory Bateson (2000: xx) says, a “truistical proposition.” “Propositions of this kind are discoverable by the mere operation of thought, without dependence of what is anywhere existent in the universe”, Hume (1993:15), noted. They are so-called “inferential knowledge.”

This is also what Ottar Brox (1990) argues regarding Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons. Using fisheries as an example, Brox considers Hardin’s allegory not as a statement about how things are in the real world, as scientists often tend to assume. Neither is it a falsifiable hypothesis or a “law”. Instead, it is a heuristic, “a part of the language we use in describing and explaining the world.” It is “a priori reasoning”, Brox notes, which enables us to see what should not be ignored. Hardin’s Tragedy explains why it is indeed within our reach to exhaust the fish stock, not as a deliberate outcome but as an unintended consequence of unrestricted individuals seeking to maximize their own utility. His allegory is a forewarning of something that might well happen. Disregarding this insight may prove to be a “tragic” mistake, a risk not worth taking.

Brox compares the “tragedy” of Hardin with Max Weber’s notion of “ideal types”, which are theoretical constructs, like his model of bureaucracy. They are not empirical representations that can be falsified. Instead, they can be juxtaposed with the real thing, the way bureaucratic organizations actually work. Notable differences leave questions for investigation. What explain the difference and what difference does it make?

Weber’s concept “was meant to be an image (Gedankenbild), that combines certain relations and events, recognizable in real life, into one consistent, non-contradictory imagined set of relations” (Brox 1990: 229). The ideal type “is no description but makes description of empirical phenomena in comparable and unambiguous terms possible” (p. 230). As a research tool, it leaves us with a question, not an answer, to whatever difference between the ideal type and the observation may be caused by. Should, for instance, a resource crisis not occur despite Hardin’s reasoning, the question of why this is the case begs for an answer.

Hardin created “epistemological panic” (as Gregory Bateson (2000) called it) among social scientists who felt the urge to check how good a fit his allegory is to reality, as they find it in the field. They have often concluded that his narrative leaves out relevant information – like a Caravaggio painting where the protagonists are sharply focused while the background is left in darkness as if it doesn’t matter. For social scientists, context always matters (Flyvbjerg 2001). In Hardin’s story, it is absent. There is for instance no community in his equation (Fife 1977). Brox observes:

“A good analytic model makes you see one aspect of a complex problem, in great clarity, but you always risk that it makes other important details of the same phenomenon disappear from your view… The CPT (common property theory, SJ) exposes the tragic potential of natural resources being free and accessible to all, but it easily prevents one from seeing that commons involve opportunities which are far from tragic for the people involved, but rather necessary for the maintenance of local communities and even national cultures” (p. 232).

To recognize opportunities, we must consider who the protagonists are and how they are positioned relative to each other. We must look for who and what is missing inside and outside the picture frame. Likewise, we must explore motives: What if fishers are less self-centered and more community oriented than Hardin envisions? We must assess the existence of, and adherence to rules: Is it realistic to assume that a commons that is not regulated by the state, is not regulated at all? Perhaps there is no need of a “God in the machinery” to solve the problem?

The commons research literature is rich with examples of self-governance. Elinor Ostrom’s (1990) work stands out as a modern classic. The same does James Acheson’s (1988) study of the lobster gangs of Maine. Other case studies are collected in his edited volume with Bonnie McCay (McCay and Acheson 1987). Since they published their work, a considerable literature has been added.

Alternative images

Are we really witnessing a “tragedy”, or something else that is better captured by a different metaphor? There are other classic theatrical archetypes than the tragedy to draw from. What if we image the commons as a comedy rather than a tragedy, as Bonnie McCay (1995) suggested? Or as romance or a satire? Shakespeare, for instance, operated in alle four genres. Social scientist could do the same. These archetypes are different “modes of emplotment”, as Haydon White (2015) calls them.7 They are not only different ways of telling a story, but also of explaining outcomes.

Shifting images would involve different assumptions, hypotheses, and visions. In the comedy, commoners are not unrelated atoms. Commoners form what Raymond Boudon (1981) would call a “functional system.” Here they have roles, obligations, and affinitive relations to each other. They are also more complex personalities than those in the Hardin plot. They have emotions and are playful. The commons is shared and valued as their “sacra” (Gudeman 2001), which they take collective responsibility of. The commons is what makes their community into what it is. Indeed, as Gudeman posits, the community is a commons; “a commons is maintained as the affirmation of community” …The extinction of a physical commons, is a community tragedy” (p. 30). To imagine small-scale fisheries without their embedding in local communities, would be fallacy, like a Caravaggio painting (cf. Pálsson 1991).

The comedy of the commons is also an ‘ideal type” dissimilar from that of Hardin’s Tragedy that would make us think differently about overfishing. Should a crisis occur, it must be for other reasons than those of Hardin. The commons is not necessarily an equal playing field. It is socially structured. Some actors may dictate rules and control outcomes to serve their own interests at the expense of others. In fisheries, we sometimes see small-scale fishers be pushed aside or run down by larger operators. Inequity and class divisions are endemic and the struggle for social justice and freedom is the driver of revolt. The only thing Hardin has to say is that “injustice is preferable to total ruin.”

In contrast, in the romance plot the struggle for justice is the driving force. Although Hardin may have a point, there is no necessary direct link between justice and ruin. Contrary to the tragedy, a comedy and a romance have an optimistic tone and a happy outcome. The characters are portrayed differently – more social and less self-centered, with a capacity for compassion, morality, and social responsibility. The comedy plot is corrective; protagonists are supposed to learn from their follies and vices. It celebrates creative energy, where the protagonists sort out their differences and arrive at some state of harmony.

To realize a better future for small-scale fisheries people, we would also benefit from the satire’s critical perspective, which I am applying in this text. We need to understand what is holding them back from realizing their potential. Unlike the comedy and romance, the satire does not envision a positive outcome. Instead, it offers a “negative goal”, as Brox discussed in another publication (Apostle et al. 1998), something we must aim to avoid. George Orwell, a political satirist like few others, painted such an image with his dystopian, futuristic novel “1984.” It vividly describes a future that we do not want.

Rather than adopting an image uncritically, pausing to reflect on the inherent biases and how things can be different than we imagine them to be, is never a waste of time. Mistakes tend to be expensive, and path dependency is often impossible to correct. Thinking outside the box is difficult but worthwhile – and not just as an afterthought. We should question our assumptions. They are choices we make, inspired by our images of what futures to strive for or to avert.

We should not get ourselves locked into a single image as if it is the true and only one available, like Plato’s cavemen. In the real world, a resource crisis may have other reasons and consequences than those Hardin analyses and which should be explored, such as “community failure” rather than “market failure” (McCay and Jentoft 1998). The community may not be capable of enforcing its norms and restraints. It may not succeed at installing an image of the sacra and that members are “in the same boat.” Playing with images allows us to see different things, phrase new research questions, and discover alternative avenues for action. Thus, it presents us which a choice, which Hardin believes that we do not have.

Governing from images

Jan Kooiman’ posits that images constitute “the guiding lights as to the how and why of governance” (Kooiman and Bavinck 2005: 20).

“Governing is inconceivable without the formation of images. Anyone involved in governing, in whatever capacity or authority, forms images about what he or she is governing” (Kooiman 2003: 29).

Governability, which he defines as the quality and capacity of governance, is largely dependent on the extent to which partners in governance share the same image. Without it, they would find it hard to agree on what the problems and solutions are. They would need time and effort to find some common ground for how to proceed. In Kooiman’s governance scheme (20032005), the tragedy of the commons is an image of “the system-to-be-governed”, in our case a fishery. He talks about the “fish chain”, the metaphor for the vertical relations of producers, buyers, processors, and consumers. Chain actors are interdependent in transactional and cooperative as much as competitive relationships.

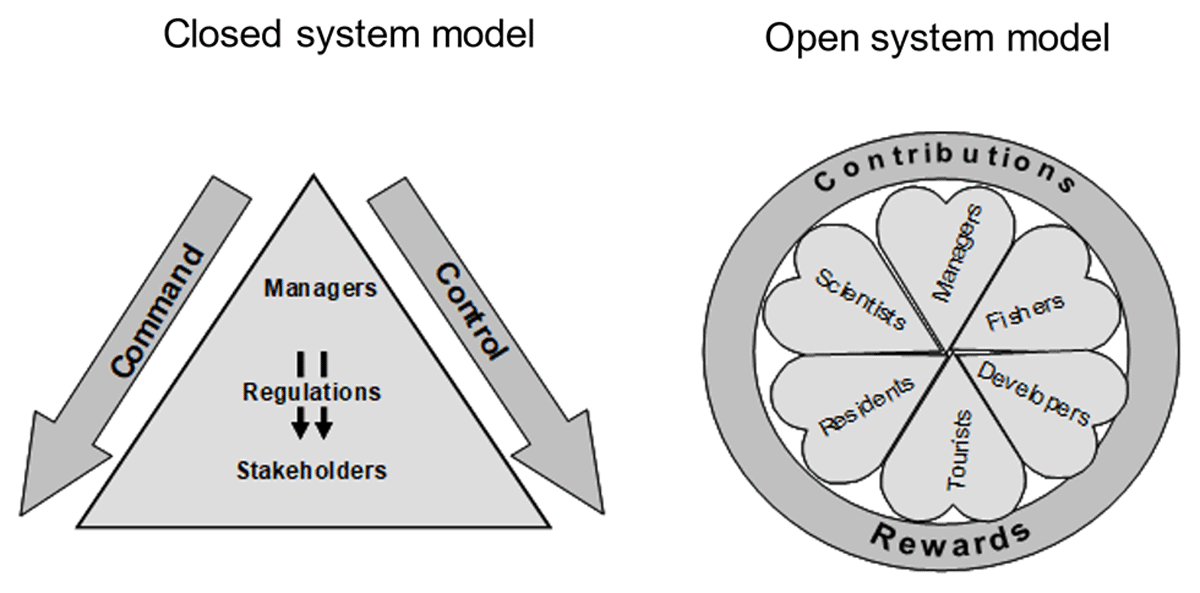

Kooiman also offers an image of he “governing system,” Picturing the governing system as a pyramid (Figure 1), with government at the summit and stakeholders at the receiving end of the chain of command and control, leaves a misleading image of how societies are governed. He observes that society has now received a level of complexity where government is not capable of governing single-handedly. It relies on the involvement and contribution of industries, markets, civil society, the academia, and the media.

Figure 1

Source: Jentoft et al. 2010.

The pyramid portrays an unmovable and impenetrable governance system. A pyramid may crumble, but never flips. It is solid and stable, like those at Giza. Kooiman’s alternative image is of an ‘open system’, like that of a rose in Figure 1. Multiple stakeholders are negotiating among themselves on how to define and solve problems. They learn from each other in the process, thus making the system dynamic and adaptive. Fisheries co-management is framed within the image of the rose rather than the pyramid – and in the image of the comedy (Jentoft 1998). It is also inherent in Kooiman and Bavinck’s (2005) definition of governance:

“Governance is the whole of public as well as private interactions taken to solve societal problems and create societal opportunities. It includes the formulation and application of principles guiding those interactions and care for institutions that enable them” (p. 17).

The concept of interaction takes center stage in this governance definition. Goals are negotiated rather than given. They may therefore change in the process. Learning is social, generated within relationships that are variably fluid, subject to political strife and coalition building. In the rose image, and Kooiman’s governance model, power is an outcome of a political process and more difficult to locate. Here, Robert Dahl’s (1961) question in his seminal study would be relevant: “Who Governs?” In the rose image, fitting Dahl’s reasoning, power plays a role on an uneven playing field, and it is relevant to ask who has it and how is it used to serve particular interests.

In the pyramid, the question of who governs is less interesting; it is whoever sits at the summit. Here, stakeholders are inactive, or reactive, whereas in the rose image, they are proactive in interaction with other actors. In the rose image they are forming coalitions and partnerships. In the comedy image, stakeholders are engaged in friendly, playful competition. In the romance image, they are involved in a struggle with other stakeholders who are their adversaries including government, as Bavinck et al. (2018) illustrate. They may be victorious in the end, as the working class in the Karl Marx’s narrative, but only if they have sufficient power to set the stage and control the outcome. “Votes count but resources decide”, the political scientist, Stein Rokkan observed (cf. Ingebrigtsen 2000).

The high number of small-scale fishers and fish workers may not matter much in the end. In the Blue Economy (Jentoft et al. 2022), they are up against corporate actors who have the capacity to control the process and determine the outcome. To level the playing field, small-scale fisheries people would need to ‘unite’, as Marx said about the workers of the world. In their struggle for social justice and freedom, they gain power by organizing. Power is a potent resource, and organization and collective action are means of achieving it (Jentoft et al. 2018; 2022).

In the Blue Economy, the rose is made up of a growing set of ‘petals’, as the number of new stakeholders in the coastal zone is increasing. Consequently, the governance system becomes more diverse, complex, and multi-scalar. New relationships are forged, shifting the dynamics of interactions. Who the stakeholders are and what they have at stake, would be worth examining. What powers do small-scale fisheries people possess relative to other stakeholders in their struggle for space and resources? How do they play their game? With the romance image, the focus is on social conflict. With the comedy, the attention is on social integration. None of these issues are present in the tragedy’s doom and gloom.

The map and the territory

Gregory Bateson argued that the major problems in the world are a result of the difference between how nature works and the way people think. Citing Alfred Korzybski (known for the theory of general semantics), Bateson (2000) posited that people often err in confusing the map with territory. “The map is not the territory” (p. 21). The territory does not get onto the map, just our image of the territory and the things that make a difference for the mapmaker and -user, such as altitudes, vegetation, population densities, transportation routes or waterways. Notably, the argument is not specifically directed at geographers who are dealing in maps. The map is a metaphor. Hardin’s “Tragedy” could be seen as a “map”, but it is certainly not the terrain, only a representation – some would say distortion – of it.

Bateson makes the same point about language: “The name is not the thing being named.” The name is just something we have agreed to call a thing, like the chair you are sitting on. You are not sitting on the name. You cannot blame the name for whatever discomfort you may be feeling. I could add; the image is not the thing that is being imaged. You may get an idea of who I am after reading my text, but I am not that image. As Bateson says (2000: 486), “you do not “really” see me. What you “see” is a bunch of pieces of information about me, which you synthesize into a picture image of me. You make the image. It is that simple.”

In Picasso’s “Line drawing of a man” (Figure 2), you must look hard to see him. I would object, though, if someone said that Picasso’s image is a representation of me. Bateson would hold that regardless of how accurate and vivid the portrait is, even with photographic authenticity and detail, it is not me.

Figure 2

Picasso, Line drawing of a man.

Hume (1748/1993: 10) is onto the same idea when he said that “all the colours of poetry, however splendid, can never paint natural objects in such a manner as to make the description be taken for the real landskip.” Likewise, one may paint movement, but the painting does not move. You may describe change, but the description does not change by itself. Poetry may capture what love is better than any other image, such as the Valentine heart, but poetry it not the love we feel. Likewise, Edvard Munch did a good job when painting “The Scream.” It is nevertheless only an image of a person’s desperation, perhaps his own.

Images, like that of Hardin, are useful in the classroom for their simplicity and for the sake of argument, but they are dangerous in the real world, as Elinor Ostrom (1990) noted with reference to Hardin. Brox argues the same: People who confuse the two should not be let lose in the real world (p. 232). The world of small-scale fisheries is richer, more diverse, and complex than any image of it can ever become. If we cannot perceive the reality of small-scale fisheries directly but indirectly through an image – as images are the only thing we have, as Kant pointed out, we should at least be open-minded about them. Images are not the reality, only representations of it. Images result from a thought process that does not stop with the governance intervention. In interactive governance, they are work in progress. Hence, fisheries governance must be pragmatic and precautious, as it intervenes into the lives and communities of real people. It is not sufficient to understand Hardin’s reasoning. At best, it is nothing more than a beginning.

The risk of misrepresenting the terrain as it is experienced by small-scale fisheries when crucial issues like inequity, injustice and power are left out the picture, is real. Acting on the image/map/name/metaphor and not the complex and dynamic traits of the thing itself, may add to the harm that small-scale fisheries people are already experiencing. This is especially a risk in a governance system where the state is imagining itself as the ‘God in the machinery’, as Deus ex machina. The state has power but not “God’s eye”, the eye that notices everything – also what is in people’s heart and mind.

To stay with Bateson’s argument, “the differences that make a difference” to the state may not be the same differences that make a difference to the people being governed by the state. What gets onto the map may be relevant to one of the two parties, but not to the other. What to look out for is not only how accurate the map is in conveying the things being mapped, but how it is used in a governance context. A map is not only an image of the terrain, but also instruments in the hands of those who want to change it, for instance in a Blue Economy context when territorial demarcations are made. Maps have power. They are empowering those who control what goes onto them.

If governors or other stakeholders act as if the map is the territory, governance failure is a present danger. “Counter-mapping” (Peluso 1995) may work as an attempt at leveling the playing field but suffers the same weakness as Bateson is alluding to. It is just an alternative portrait of the terrain, not the terrain itself. Likewise, comedy and romance are alternative pictures of the commons. They are like tragedy, ideal types, functioning as heuristics in the analysis of processes and outcomes. They are also just beginnings.

The same can be said about language, as Wittgenstein (1953) argued. Governance is language-dependent (Searle 1995), and language is power when used as a governing instrument. Those who control the language, the words that are used to define the problem and picture the solutions, control the conversation. And those who control the conversation, control the action taken. The “tragedy of the commons” provides powerful actors with language to steer the process in their own favor. In his ‘Prison Notebooks’, Antonio Gramsci argued that power has a linguistic dimension.8 When language and the images and metaphors used to frame the discourse, acquire a status of “common sense”, people have problems thinking of their situation being other than it is. Then, the “hegemony” of powerful interests is maintained.

The issue is not only the definition of concepts, which are nothing else than words in a sentence in a narrative on a paper, but how they are used to control the situation. Hardin’s language may have a disarming effect on those who see the situation in small-scale fisheries differently, especially when adopted by powerful institutions. Scientific language may work in the same way. Concepts may not be understood by those that are at the receiving end of them, but they learn how they are used in a governance context because they experience their performativity and must live with the consequences. Small-scale fisheries people may be unfamiliar with the “map” but have intimate knowledge of the “terrain.”

Freedom in the Commons

In fisheries, the Tragedy of the Commons has obtained hegemonic status as a commonsense image of what is considered the root problem, the freedom of the commoners. It has served the idea of bureaucratic power; the idea of a situation that without intervention would become chaotic and detrimental. In fisheries, resource managers are today’s embodiment of Leviathan, the image that Thomas Hobbes (1651/2010) put forward.

Awareness of other theatrical images is liberating to the mind and, in the last instance, to the “subordinate” small-scale fisheries people who are living with the Hardin legacy. Social scientists have a role to play in creating that awareness, in demonstrating that there is a different light outside the cave and that Leviathan is not there waiting for them if they should leave behind the image the “Tragedy.” Social scientists exploring the action space that other images may reveal, are part of the same freedom project that small-scale fisheries people are engaged in.

Bateson (2004: 21) argued that when we realize that the map is not the terrain and the name is not the thing that is being named, or as I phrased it, that the image is not the thing being imaged, we experience “something resembling freedom.” This is not the freedom Hardin is talking about, i.e., the unfettered freedoms fishers enjoy in the absence of rules. Instead, it the freedom that Plato discusses – the freedom that comes with education and enlightenment. This freedom is not only good for the soul. It also makes people “more capable of participating … in public life” (Plato 1980: 213). With the “conversion” that education brings (p. 211), “you will know what each of the images is, and of what is an image, because you have seen the truth of what is beautiful and just and good.” (p. 213). It is likewise the freedom that comes from the interactive learning that Kooiman is discussing as part of his governance theory. You learn from sharing experiences and insights with others. You learn from other people’s learning if the governance process allows for communicative interaction, from listening to them.

Amartya Sen (1999) noted that freedom is not just the aim but also the condition for development. Freedom is an enabling resource. If your hands are tied or if you are stuck like Plato’s cavemen, your agency is impeded. This also holds true in small-scale fisheries management system framed by Hardin’s image where their agency is perceived as the root problem (Jentoft et al. 2010). Small-scale fisheries people would be in a very different situation if Sen’s idea of freedom ruled, rather than that of Hardin. Instead of limiting their freedom, the aim would be to enhance it, not by abandoning rules but by creating different rules. These would be rules that fit their reality, their actual responsibilities and opportunities, rather than our images of it. Building their capacity and capability would be one thing. Changing roles and relationships of power would be another. In co-management arrangements, the ‘God in the machinery’ is redundant. Here. fishers are equipped to govern their own affairs as equals in constructive cooperation with other stakeholders. Interactive learning would be a central endeavor, but that cannot occur if participants are unfree. Co-management is about empowerment. Empowerment is also about enlightenment, and they both are about freedom.

Notes

[1] The paper expands on my keynote address at the Fourth World Small-Scale Fisheries Congress Series, “Imagining the (un-)imaginable”, Sept. 11, 2022, Valetta, Malta.

[2] Sting sings it beautifully: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9P8ROHF_35Q.

[5] Plato, 1980 edition. The allegory is in Book VII.”

[6] Which my late friend, the Renaissance literary and culture scholar, Roy Eriksen explained to me.

[7] The four literary genres inspired my book (Jentoft 1998).”

Acknowledgements

My colleagues Jens Ivar Nergård and Knut H. Mikalsen commented on a draft of this paper. Greta Jentoft carefully read the text and helped with polishing it. I also benefited from three anonymous reviewers. I appreciate the support of TBTI, the international researcher network on small-scale fisheries and Ratana Chuenpagdee who invited me to give the keynote address from which this paper originates, (www.toobigtoignore.net).

Funding Information

The publication charges for this article have been funded by a grant from the publication fund of UiT – The Arctic University of Norway.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.