Introduction

We recall a formative moment, drinking expensive wine with scholars and professionals after a conference in Paris where we each presented our work on land issues in the Global South. Someone who works for a network of community-based organizations supporting the “urban poor” in the Global South talks about her work of bringing these organizations together. When we ask about the already existing links between these organizations, she answers: “They are not connected globally, that’s where we come in.” This is an urbane moment, and we consider ourselves cosmopolitan internationalists. After this conference, we will travel to other cities around the world. We assume the communities we work with do not travel; they remain in place, and only connected to the international stage because of people like us, and the global networks we work for.

This article argues that the connectedness between communities of low-income urban dwellers is often ignored or undervalued in the work of supporting organizations, as well as in policy mobilities studies. These communities are seen as mere local case studies and their relationality remains disregarded and unsupported. A “community,” for us, is simply a place-based group of people. Members of the community may be part of some type of organization, which we call a “community-based organization.” We examine the role of “supporting organizations,” defined as those organizations (NGO’s, networks, institutes, foundations) that assist communities or community-based organizations in planning or development. The tensions that arise between professionals/scholars—often, but not always, from the Global North, or from wealthier neighborhoods—and residents in these communities in the Global South need to be analyzed. We use the global Community Land Trust (CLT) movement, which continues to grow because of ongoing community-to-community exchanges, as an example to highlight the importance of these exchanges of experiences and best practices in introducing new policies and planning instruments in cities. A more explicit focus on the contributions of low-income urban communities to policy mobilities can help the development of more effective approaches to address the needs of the “urban poor,” who will soon represent two-thirds of the global population (Barthold, 2019, p. 149). According to one of our respondents, social change is only possible if grassroots organizations are treated as stakeholders in the process, thus not merely as case studies.

CLTs are nonprofit organizations that hold land on behalf of a place-based community, while serving as the long-term steward for affordable housing on behalf of that community (CLT Center, n.d.-b). We consider a CLT a policy—and therefore useful to study in a policy mobilities context—as it is created for the benefit of the (low-income) communities it serves. According to John E. Davis, “[t]he CLT is guided by—and accountable to—the people who call this place-based community their home. One-third of the CLT’s board of directors is nominated and elected by members who live on the CLT’s land. One third of the CLT’s board is nominated and elected by members who reside within the CLT’s targeted “community” but do not live on the CLT’s land” (Davis et al., 2020, p. 4). The first CLT, in the form we currently know it, was established by members of the Civil Rights Movement in Georgia, USA, after its founders were inspired by other communities living with a variety of collective forms of land holding across the world, as we will describe below. CLTs have now become a widely used land instrument internationally fighting gentrification and ensuring permanently affordable housing.

A new push in the global movement has happened when a CLT in a self-built neighborhood in San Juan, Puerto Rico, the Fideicomiso de la Tierra del Caño Martín Peña (hereafter “Caño CLT”), won the 2015–16 World Habitat Award (WHA), a prestigious prize awarded by the British nonprofit organization World Habitat (WH)1 in collaboration with UN-Habitat. The Caño CLT is one of the first CLTs in Latin America and the Caribbean. Planned and designed in 2004 by residents of seven neighborhoods surrounding the Martín Peña waterway (“caño” in Puerto Rican Spanish), a highly polluted tidal channel that is part of the San Juan Bay estuary, the Caño CLT regularizes land ownership and prevents displacements, which might have otherwise resulted from the planned dredging of the waterway. The WHA raised the Caño CLT’s international profile and intensified their solidarity with and outreach to similar communities in other countries, as we will describe.

This article is based on historical data of the CLT movement and on data from participatory-action-research (PAR) during several international exchanges that occurred between 2017 and 2022, which the authors helped organize to facilitate the discussion on community-led mechanisms to tackle conditions of poverty and urban displacements.

We start with an overview of literature on policy mobilities discussing the lack of explicit focus in much of this literature on communities’ lived experiences and mobilizations, followed by an explanation of our methodology. Next, we examine how the global CLT movement grew from community exchanges. We recount how the CLT was introduced in Puerto Rico, and how the Martín Peña communities reshaped the original instrument to fit their own realities. We explore how, doing so, the Caño CLT became an example for communities in other parts of Puerto Rico and the world, studying some key activities and institutions that have supported grassroots exchanges. We analyze exchanges that happened between the Caño CLT and the Brazilian NGO Catalytic Communities, leading to the latter spearheading the creation of a CLT in Rio de Janeiro. Finally, we make conclusions on the importance of community-to-community exchanges in policy mobilities.

Whose ideas travel?

There is a vast body of contemporary literature looking at urban policy mobilities (e.g. Peck & Theodore, 2010; McCann & Ward, 2011; Roy & Ong, 2011; McCann, 2011; Oosterlynck et al., 2019.) This literature looks at how new policies get introduced in cities, how ideas for policies travel globally, and who are the “agents of transfer.” The traditional approach to “policy transfers” —i.e., models to be “replicated” or “adopted” by worldly decision makers from a global marketplace of policy solutions (Theodore, 2019)—has been replaced by a policy mobilities approach. This approach is geographically sensitive to the importance of sociospatial contexts in creating and validating effective policy solutions, and the interconnectedness of policymaking locations (Theodore, 2019). Policies “rarely travel as complete ‘packages,’ they move in bits and pieces—as selective discourses, inchoate ideas, and synthesized models—and they therefore ‘arrive’ not as replicas” (Peck & Theodore, 2010, p. 170).

Analyzing the role of elites in variegated neoliberalization, these authors describe the “agents of transfer” mostly as worldly experts and elite communities of practice. McCann, for example, in proposing an Urban Policy Mobilities research agenda, lists the communities of policy mobilizers as “local policy actors, the global policy consultocracy, and informational infrastructures” (2011, p. 114). Peck and Theodore write that traveling ideas are “constructing symbiotic networks and circulatory systems … enabling cosmopolitan communities of practice and validating expert knowledges” (2010, p. 170). McCann and Ward define policy actors as “politicians, policy professionals, practitioners, activists, and consultants” (2011, p. xiv), and describe how they are “shuttling policies and knowledge about policies around the world through conferences, fact-finding study trips, consultancy work, and so on” (ibid). None of these categories do, at least not explicitly, include the actual people whose lives are affected by those traveling policies, specifically low-income communities in urban settings.

These low-income urban communities, however, are making significant contributions to these policy mobilities. Their ideas travel too, and this demands a more direct analysis. In less than two decades two-thirds of the global population will be low-income urban dwellers (Barthold, 2019, p. 149). It is therefore urgent to be more explicit about the strategies, tactics, programs, and instruments the “urban poor” develop—and how these subsequently travel and get translated into policies elsewhere—as these are direct responses to their most pressing needs. A new focus on their contributions to policy mobilities can help the development of policies that are more effective to address the needs in these communities.

The global CLT movement as commons-based resistance

This article centers the role of communities in the global CLT movement, using the circulation of ideas around CLTs as land-based commons to explore how policies grow from the ground-up, thanks to community-to-community exchanges. “Land-based commons” refers to the rights to access, use, and transfer of land that are shared among a community—or the community is claiming the right to do so (Simonneau et al., 2019). As Susanna Bunce (2016, p. 135) puts it in her article on East London CLT activism: CLTs are fascinating examples of commons-based resistance against land commodification as they challenge traditional land regulation and ownership, while resisting speculation and capital accumulation in urban contexts.

Following a policy mobilities approach, the growing international CLT movement recognizes that no two CLTs are the same. Too many local elements are at play for CLTs to function alike. A CLT is therefore hardly a model (Davis et al., 2020, p. xxviii). This word—model—suggests it can be “brought” in a package from one place (by default, the USA) to another, underestimating the community organizing processes that require the establishment of each new CLT. Similarly, the CLT is not an American model. The first CLT as we know it today was inspired by preceding forms of collective land tenure worldwide, as we will discuss. A growing number of communities around the world use key elements of the CLT: community-led development on communally owned land.

In tracing Liverpool’s urban CLT movement, Thompson (2020) uses a policy mobilities perspective to analyze the assemblage of elements, components, discourses, practices, materials, and actors, sourced from both local and global contexts that make the movement. The intricate integration of globally mobile ideas with historical “place effects” generates, he says, novel compositions of policy models and social movements (2020, p. 85). Thompson highlights the importance of conferences and study tours in the dissemination of the CLT idea, which he refers to as “convergence spaces” borrowing the term of Temenos (2015).

There is a large body of literature that explores the importance of South-South learning in the circulation of best practices in urban policy. Of interest is the study by Claire Simonneau (2019) on the global circulation of CLTs between the USA, Belgium, and Kenya. Contributing to literature on South-South policy mobilities, she argues for fully reintegrating the South into the analysis of the circulation of ideas for urban policies, and for highlighting “non-dominant”, nonconformist, anti-neoliberal ideas. Foregrounding the South into the analysis of the circulation of urban models allows us, she writes, to focus on drivers of change other than finance, such as human rights approaches, and anti-poverty strategies (Simonneau, 2019, p. 6). Françoise Vergès, (2021, p. 16) writing about the people who resisted against Western colonization, says: “Ignorance of the circulation of people, ideas, and emancipatory practices within the Global South preserves the hegemony of the North–South axis; and yet, South–South exchanges have been crucial for the spread of dreams of liberation.”

Similarly, postcolonial theorists increasingly acknowledge that cities in the Global South do not adhere to Western-centric policy trajectories. Instead, these cities are recognized as fertile grounds for experiments that redefine the notion of “global” urban practices (Ong, 2011, p. 2). Jennifer Robinson argues against the academic division that centers theoretical approaches solely on the West, whereas the once-called ‘third-world’ is seen from a passive, receiving, development lens (2002, p. 531). In much of this literature, however, policymaking “from below” refers to the political agency of the city; the analysis fails to go further “down,” i.e. to the level of the residents. The role of urban dweller communities—those most affected by traveling policies, and how they influence city policy—is, at best, implicit. When their role does get acknowledged, the analysis remains on the local—not the global—scale.

New International Solidarities

Many scholars have studied international solidarity and transnational activism as a vector for traveling ideas and policies. This literature indeed recognizes that ideas of social justice travel globally and are not just driven by local and national contexts. Temenos (2015, p. 15) argues that looking at who is able to be mobile, who is excluded from mobility, is a key question for the geographies of social movements. Almeida & Chase-Dunn (2018, p. 1.3) discuss the influence of worldwide economic and cultural developments on social movements. But even in some of this literature on transnational social movements which recognizes the role that non-state actors play, the focus is mostly on NGO’s or other types of supporting organizations (see for example Sikkink, 2005). The role members of urban communities play in the growth of these movements—or how these supporting organizations collaborate with the communities—is not made explicit.

Other authors do call for the inclusion of local people’s experiences and mobilizations in policymaking. A “peopling” of urban policy mobilities research is needed to enrich urban policy mobilities research, Temenos and Baker write (2015, p. 842). Mehta et al. (2014), who studied the right to water in the Global South, observed the role of elite biases in policy making in the failure to achieve certain rights to environmental justice. “It is the poor who largely bear the brunt of environmental degradation and pollution,” she writes, but “their interests are both ignored and by-passed due to elite biases.” Baker et al. (2020) argue to advance our understanding of the role of “non-elite” actors in mobilizing policy knowledge and advocate for an analytical expansion “into the ordinary” involving often ignored actors who influence policymaking from the “front-line” or “street-level.”

Crucial to our argument is Doreen Massey’s (2011) term “counterhegemonic policy mobility,” which denotes how this “ordinary” knowledge can challenge hegemonic thought and can alter power relations. She writes about the relationship between “relationality” and “territoriality” in policy circulation. According to her there is a contrast between a focus on connections (and lack of connections) —“relationality”—on the one hand, and a focus on places, on the other”—“territoriality” (Massey, 2011, p. 3). Indeed, we see that the “relationality” between community-based organizations and communities—among themselves—is often underestimated (for example as described in the opening sentences of this article), undervalued, and understudied. Instead, their “territoriality” is exaggerated, seeing communities as mere local case studies. When communities are mentioned in literature, they are often described in the phrase “local communities”, as if communities only act locally. Almeida & Chase-Dunn (2018, p. 1.3) in their study of the globalization of social movements agree that there indeed is a greater synchrony and connectedness among groups than currently described in literature.

Epistemic justice and traveling knowledges

In earlier studies of international policy transfer, an “epistemic community” was understood as “a network of professionals with recognized expertise and competence in a particular domain and an authoritative claim to policy-relevant knowledge” (Haas, 1992, p. 3). In this view, knowledge can only be produced in institutions, universities, laboratories, companies, not in the everyday context of streets or communities. The ways in which such institutional knowledge or urban policies are actually based on the work of communities are ignored. Perhaps, this perspective is still partly in existence today.

Contrasting to these earlier studies, in more recent literature on for example environmental justice, we read that “conflicts over the environment are epistemic struggles wherein other forms of the political, other economies, other knowledges are produced and theorized, and hegemonic worldviews are questioned and reformulated” (Temper & Del Bene, 2016, p. 42). This applies equally to conflicts over the tenure, use, and development of land. To question the hegemonic worldview that individual forms of land ownership are the only path of development (e.g. De Soto, 2000) is to resist the whole epistemology of the political, economic, and cultural world system and its perceived absolute institutions. The radically different knowledge practices that emerge from these conflicts also travel; these ideas are mobile and influence other communities. The communities who resist injustices collectively construct another, counterhegemonic worldview. In these types of policy mobilities a global “counterhegemonic solidarity” (Massey, 2011, p. 5) emerges. Similarly, Arturo Escobar sees land struggles as fundamentally epistemic struggles: “The knowledge connected with these struggles is actually more sophisticated and appropriate for thinking about social transformation than most knowledge produced within the academy” (2016, p. 14). Without this knowledge actual social change becomes impossible.

Hess and Ostrom (2007, p. 5) describe knowledge as a commons: it is a resource that is jointly produced, used and managed by groups of varying sizes and interests. But the question we address in this article is: Who gets to participate in these groups that produce, use, and manage knowledge? Or better said: whose participation is acknowledged at the different levels at which knowledge construction happens—not just the local level? Participation in policy construction is emphasized as a crucial factor for successful commons management, by scholars such as Hayes and Murtinho (2023). However, granting decision-making rights to communities, they say, does not automatically guarantee inclusive or equitable decision-making processes. For a true commoning of knowledge all voices need to be heard, acknowledged, and made explicit.

Our article calls for the explicit inclusion of those voices in policy mobilities studies. It tracks the global CLT movement which results from community-to-community learning on collective land tenure and zooms in on the role of the Caño CLT in the circulation of ideas around CLTs in the Global South. Community-to-community exchanges of knowledge and ideas need to be included as a critical, highly effective component in the analysis of policy mobilities.

Community-engaged research

Both authors of this article have directly supported the Caño communities during a period of eight and 20 years respectively. The first author got involved with the Caño communities since they won the WHA for which she was an evaluator. The data used for this article were collected during her doctoral research. The second author was on the Board of Trustees of the Caño CLT and instrumental in its establishment. Both authors are on the Executive Committee of the Center for CLT Innovation (hereafter “the CLT Center”), an organization we helped establish with the aim to encourage the international CLT movement and support community land trusts and similar strategies of community-led development on community-owned land in countries throughout the world.

The data we used for this article are retrieved from the historical archives of the CLT movement compiled by the two founders of the CLT Center, John E. Davis, and Greg Rosenberg, and from interviews with people directly involved in the described events. We retrieved data from PAR with the Caño communities during 10+ international community exchanges that we helped organize. Our conclusions are also based on data retrieved from helping other communities establish CLTs, in the frame of a study conducted on the potential for CLTs in Rio de Janeiro for the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (LILP) in 2018. We kept notes during these meetings and conducted in-depth interviews with participants and community leaders. The research was multi-sited, conducted in different locations where the community exchanges took place, in Puerto Rico, Brazil and online. We actively helped create these transnational networks and policy circuits that are used as the sites for this research, and these continue to develop and be active.

We do not claim to be “objective” observers of communities, as we are very much a participant in this research ourselves, with our own feelings, contradictions, and political stances. We employ the research method of autoethnography, inserting personal experiences in the analysis. Several events and partnerships in which we have been closely involved were critically analyzed, using emails, WhatsApp exchanges and personal fieldnotes as data. This method helps us address the paradox of being a researcher writing on behalf of the communities whereas we argue for their participation in all matters that affect them. Many of the ideas presented in this article are generated by members of these communities and the supporting staff, but we had the time and the university funding to do the largest portion of the work of writing it down. These divisions of responsibilities were discussed among all participants.

In her essay on “Situated Knowledges” Donna Haraway (1988, p. 581) writes: “I would like a doctrine of embodied objectivity that accommodates paradoxical and critical feminist science projects.” Traditional ideas of “objectivity” are illusory, she says, all knowledge is constructed through social, political, and historical processes. But, as Sherry Ortner (2019) says, taking such an engaged feminist stance does not stand in the way of a commitment to the “principles of accuracy, evidentiary support, and truth,” the basis of all scientific work. “The only difference,” Ortner writes, “is that the biases of work that does not define itself as engaged tend to be hidden, while the biases of engaged [research] are declared up front.”

The community-driven history of the CLT movement

The global CLT movement grew because of community-to-community exchanges. The first CLT, New Communities Inc., was founded in the 1960’s by members of the civil rights movement. A community of tenant farmers in Georgia, USA, on land owned by white landowners was evicted because of their participation in the movement, after which they sought true economic emancipation through ownership of the land they had been cultivating for decades. Pooling money they bought 6,000 hectares, combining communal land ownership with individual home ownership and cooperative organization of agriculture.

Charles and Shirley Sherrod, among the founders of New Communities Inc. were inspired by other similar forms of landholding around the world, such as communal lands of different indigenous peoples who live on indivisible collective land property with common use of the natural resources on which all depend. They were also inspired by the “land gift movement” in India, whereby wealthy people would donate land to groups of impoverished people. The donated land was to be held in “trust” by a village council and leased to local farmers (Sholder & Hasan, 2020). Another precedent is the moshav ovdim founded by Jewish settlers in the early 20th century on land in what was then Palestine and now Israel. The Moshavim are “workers’ cooperative agricultural settlements,” where the land was cultivated collectively, but households were managed independently by their members. The Sherrods, among others, went on a study trip in 1968 where they met residents of the moshav ovdim, after which they founded New Communities Inc. (CLT Center, n.d.-a).

Currently, there are around 545 CLTs around the world. No two of these CLTs are the same, never traveling as “complete packages,” to use Peck and Theodore’s phrase. This demonstrates the integration of a global idea—the combination of collectively stewarded land ownership with individual home ownership—with historical “place effects,” which is what makes the CLT movement so diverse. Several CLTs were founded after community activists and professionals visited other CLTs or learned about them at conferences, demonstrating the importance of Temenos’ “convergence spaces,” and the role of supporting organizations.2

The Caño CLT: born from community-driven mobilities

The Caño CLT also demonstrates the importance of community-to-community exchange in policy mobilities. Learning about core elements of the CLT from residents living in one, Martín Peña residents created a new organization that serves their specific needs, living in an “informal” settlement, i.e. a neighborhood built without recognized ownership of the land.

The Martín Peña communities are home to approximately 21,000 residents, and strategically located adjacent to the financial district. In the 1930’s, impoverished landless farmers constructed precarious crowded towns on mangroves swamps along the Martín Peña waterway, looking for jobs in the city. By 1975, the government adopted on-site rehabilitation public policies and provided paved streets with sidewalks, potable water, and electric power. A law was enacted for families to acquire a formal individual land title for the symbolic price of $1 US, but in the Martín Peña communities, by 2002, almost half of the households lacked those titles. By that time, the waterway was completely degraded and contaminated, and life was harsh.

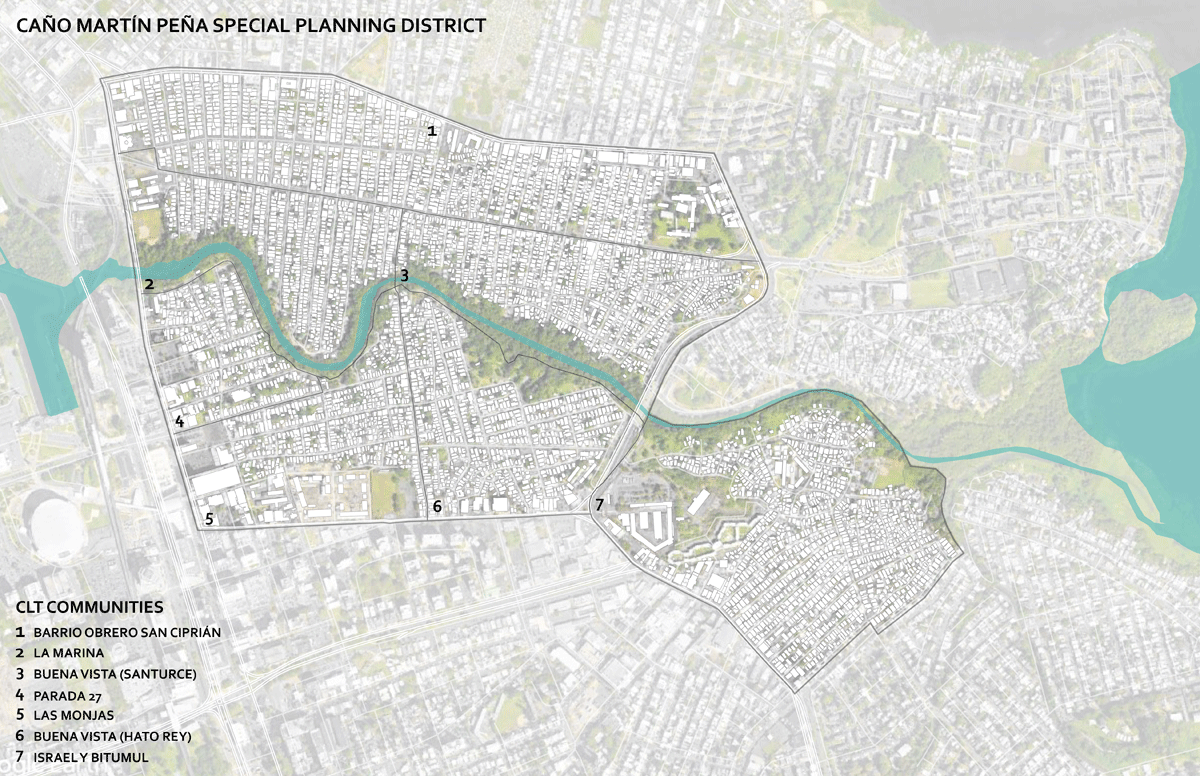

In 2002, the residents were informed of the government’s plan for dredging the caño. Represented by their elected community leaders, they demanded participation from the very beginning of the planning process. From experience, they knew that dredging would lead to gentrification, as it would make the area significantly more attractive. After two years of intensive participatory planning-action-reflection with 700 community activities assisted by professional urban planners and social workers, the communities were designated as a special planning district (the District, see Figure 1). They drafted a Comprehensive Development and Land Use Plan that contemplated community control of the 200 acres of the District. Residents without land titles expressed a need for secure and inheritable land tenure.

Figure 1

The Caño Martín Peña Special Planning District. Source: Line Algoed and Kyle Kalmar.

After thorough analyses of the type of land tenure that would fulfill the expressed necessities, residents opted to explore the CLT, hardly known in Puerto Rico at that time. Needing to hear from someone skillful in CLTs, they invited Julio Henríquez, the then President of the Board of Directors and resident of the Dudley Neighborhood, Inc., a CLT in Boston, Massachusetts. This meeting reaffirmed that a CLT could address their needs, although it had to be transformed to their context with valid recordable perpetual surface right titles to the approximately 1500 families that lacked security of tenure.

The Caño CLT was born because of this community mobilization. This CLT allows the restoration of the ecosystem, while avoiding the involuntary displacement of residents that such an infrastructure project would entail. The government transferred the 200 acres of public land within the District to the CLT. The CLT’s Board of Trustees comprises a majority of members of the communities, who have control of the land within the District and made it available for the projects related to the dredging of the caño and the construction of new infrastructure.

The Caño CLT as a driver for circulation of CLTs in the Global South

The nonconformist approach to addressing tenure insecurity and the community planning practices of the Caño CLT were recognized with the 2015–2016 World Habitat Award. Since then, the CLT became an inspiration for communities living in insecurity of tenure around the world. Residents actively engage in global solidarity work, driving circulation of ideas. This demonstrates they are not just a local case study (Massey’s “territoriality”), but an actor of policy mobilities (“relationality”). First, this solidarity work led to the creation of two other CLTs in Puerto Rico, with a third one being considered. The Fideicomiso para el Desarrollo de Río Piedras is intended to revitalize the distressed economy of Río Piedras in San Juan and provide affordable housing for low- and moderate-income residents. The other CLT, the Fideicomiso de Tierras Comunitarias para la Agricultura Sostenible was created to acquire farmland and make it affordable for landless farmers. Another CLT is being considered in an African Puertorrican community in the municipality of Loiza. The community hopes a CLT will halt displacements, because investors, attracted by the astonishing ocean views, started grabbing land for short-term rentals after the 2017 hurricanes.

Secondly, the Caño CLT organized several international exchanges that drove the mobility of ideas around collective land tenure in the Global South, especially in “informal” settlements. The Caño CLT organized 10+ international exchanges with organized communities and accompanying professionals eager to learn new ways to alleviate the globalized housing crisis and strengthen ties of solidarity. In 2017 an international peer exchange was organized in collaboration with World Habitat hosting 14 professionals who traveled to Puerto Rico to learn about this new application of the CLT instrument. One of the participants was Greg Rosenberg from the USA who, inspired from what he learned during the visit, later co-founded the CLT Center to help support this innovation in CLTs, an initiative the authors of this article quickly joined, alongside Caño CLT staff. The CLT Center now promotes and supports CLTs and similar strategies in countries throughout the world. The Center also publishes under its imprint Terra Nostra.

In May 2019, 49 people from 17 different countries from Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, Europe, and the USA traveled to the Martín Peña communities, sponsored by the Ford Foundation, to share strategies on fundamental rights and the strengths of collective land ownership in response to the major political economic, social, and environmental challenges. The methodology of these workshops facilitated critical thinking among community leaders, who were accompanied by one person from a supporting organization. Attention was given to community residents being a majority in the room, not the employees of the supporting organizations, which significantly influenced the dynamics of the sessions. People felt safe to share experiences and think of ways to overcome challenges, without professionals guiding the discussions based on what, according to them, is possible or not. It was a safe space to reflect on different forms of communal land tenure, not to be “trained” about the CLT instrument.

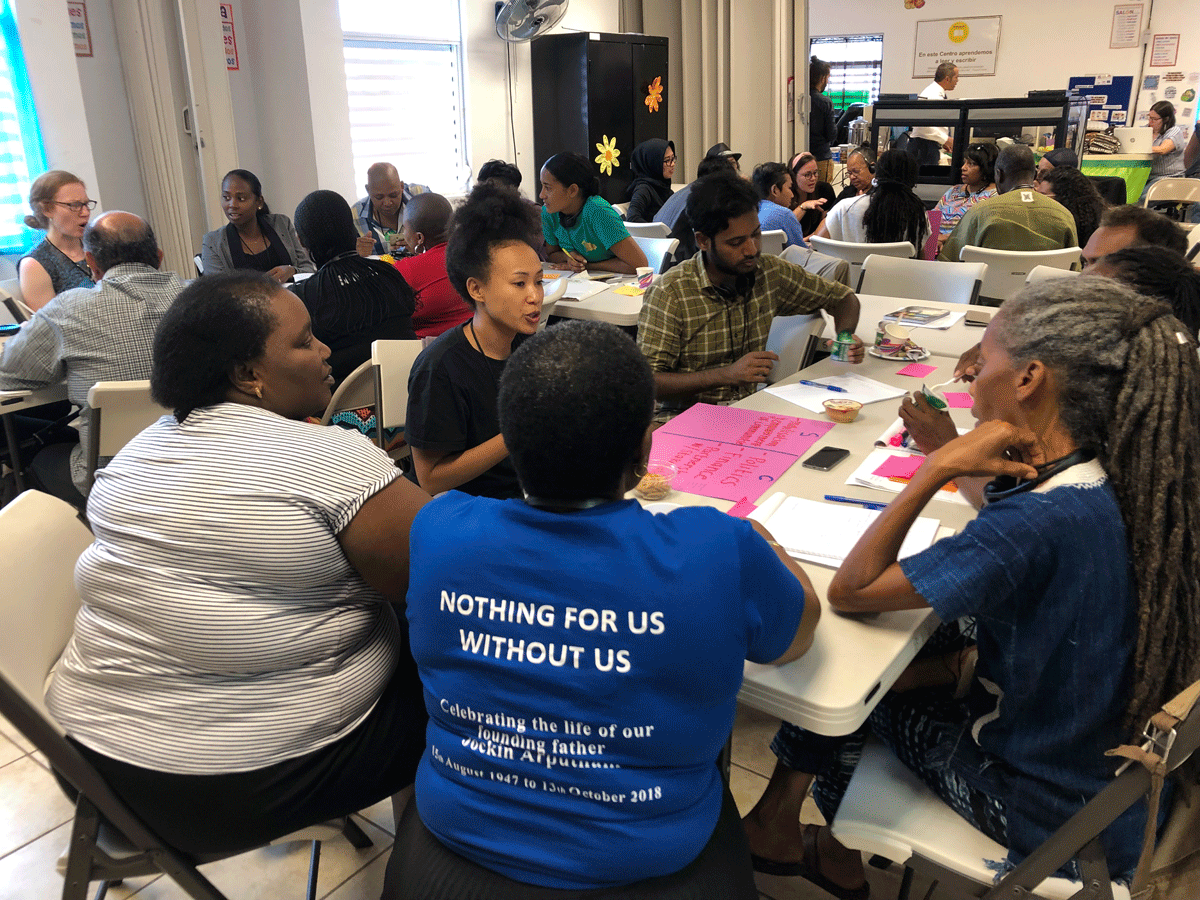

In the evaluation of this exchange, participants said that by sharing experiences, they realized how global the fight for social justice and equity is. “This fight is everyone’s, and collectively we are stronger,” Caño community activist José Caraballo Pagán remarked. These experiences must be shared among those who face injustice, not (only) among professionals or scholars of these issues. It sounds like a truism to say that there should be no discussions about “the community” without members of that community participating; yet this still happens very often. “Nothing for us, without us,” the T-shirt of a participant read (see Figure 2). In these exchanges the emergence of Massey’s “counterhegemonic solidarity” becomes noticeable, by way of questioning ingrained institutions such as private property. “We are fighting ancestral battles against the displacement of our people,” a participant said. These “convergence spaces” facilitate the discussion on epistemologies that may lead to social transformation. It is in these discussions that commoning of knowledge happens, acknowledging all voices and all levels at which knowledge construction happens—a global, not just local level.

Figure 2

Community-to-community exchange hosted by the Caño CLT in May 2019. Source: Line Algoed

The global connectedness/relationality generated by these peer exchanges was materialized after Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico in 2017. The Martín Peña communities were severely affected: 75 families were left without homes, approximately 800 roofs were lost or severely damaged, and 70 percent of the community’s land was flooded with contaminated water (Algoed & Hernández Torrales, 2019). The international work of the Caño CLT was the foothold for an immediate response from the Puerto Rican diaspora and people from around the world. “We’ve always been organized, that’s why we received help. We are recognized, people know that the help they give will reach each one of the residents of the community,” a Caño community leader remarked in an interview, demonstrating the importance of the CLT’s global connectedness (including with diasporic networks) in the community-driven hurricane response. Resources for swift relief were provided, facilitating recovery, and ensuring the safety of residents (Vincens, 2017).

The relation between communities and supporting organizations

One of the most salient contributions of the Caño CLT internationally has been the exchanges with Brazilian nonprofit organization Catalytic Communities (CatComm)3 and favela residents in Rio de Janeiro (see Figure 3). With funding from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (LILP), a think tank based in Cambridge, Massachusetts (USA), the Caño CLT and CatComm conducted a research project to study the feasibility of establishing similar CLTs in other informal settlements in the Global South, specifically in favelas in Rio de Janeiro. LILP has been a crucial actor in the global circulation of land policies for decades. Their publications in the early 2010’s have facilitated the dissemination of knowledge on CLTs, leading to new CLTs emerging across the Global North (see e.g. Davis, 2010). Thanks to the importance of the Caño CLT for other informal settlements in the Global South, the LILP took a renewed interest in CLTs.

Figure 3

Exchange between Caño CLT and a Favela community in Rio de Janeiro, August 2018. Source: Line Algoed.

In organizing the research project on the feasibility of CLTs in Brazil, it needed to be stressed that the Caño CLT residents had to be directly involved, and that it should not just be carried out only by appointed researchers, who were not favela or Martín Peña residents. In an article published by a fellow of the LILP, it appeared that the Caño CLT initially was seen as a local initiative and a powerful case study, but not as an active participant in the internationalization of CLTs in informal settlements. The article described that the Caño CLT was “one of the first attempts to create a CLT in an informal area,” and that “the Lincoln Institute is supporting [Catalytic Communities’] efforts to ascertain the legal and political feasibility of CLTs in Brazil” (Flint, 2018). The Caño’s leading role was set aside. The Caño CLT and CatComm pushed back, insisting that an exchange between the communities should be central in these efforts. Later, the LILP recognized how important it had been to actively involve the community in this and other projects (CLT Center, 2021).

This suggested that there was a different understanding about the role of professionals. One of the reasons of success in the Caño is that from the onset the community leads in the discussions on why CLTs may be a potential way of addressing tenure insecurity. Professionals take a step back and collaborate by providing sound information that would help residents in the decision-making process when needed. The role of professionals is to accompany the community’s own thought process, not to suggest to them a certain “model” or instrument. The residents of the community must be a majority in the room, and the conditions should be conducive to ensure they do not feel intimidated when participating with professionals. In the Caño, community social workers were involved from the beginning to facilitate—not to lead—the planning-action-reflection process. Lawyers, urban planners, architects, and engineers only stepped in after the community had defined its goals; professionals would then help to implement that vision. If professionals lead, they may guide the discussions towards what is possible and what is not possible, according to them, possibly stifling ambitions. Organizing an exchange on the potential of CLTs in favelas in Rio without community leaders present would have given a completely different outcome. Eventually, a community-to-community exchange took place in Rio in August 2018 with a strong presence of community leaders, which successfully led to the creation of the organization “Favela CLT,” who are supporting pilot CLT projects in three favelas, with increasing interest across Brazil. In December of 2021, thanks to the efforts of this organization and numerous community leaders, a first Brazilian law acknowledging the CLT was approved, effectively making the CLT instrument a reality (Termo Territorial Coletivo, n.d.). The exchanges between Favela CLT and the Caño CLT continue with regular virtual meetings and other visits of the Caño CLT staff and community leaders to Brazil. In this example, we clearly see the connectedness among low-income urban communities, which brings about transnational commons-based resistance to land commodification.

Conclusion

Policy mobilities scholars and organizations supporting low-income urban communities often underestimate the relationality of these communities, instead focusing on their territoriality. The history and current development of the CLT movement—and specifically the role of the Caño CLT—demonstrates that policy ideas do travel among communities which leads to noteworthy counterhegemonic solidarity movements. We have argued that these communities need to be recognized as key actors in policy mobilities if we want to truly understand how effective policy solutions are created and validated, and how social transformation happens.

We described how the idea of a CLT found fertile ground in the Martín Peña communities through a visit from a community leader living in the Dudley Neighbors CLT in Boston, USA, at that time also the President of the Board of Trustees of this CLT. Martín Peña community leaders found convenient the idea of this form of collectively stewarded land ownership to put a halt to speculation and community fragmentation that had been happening in the decades prior. Yet, they did not “adopt the model;” it was not “transferred” to their community. Instead, during a two-year in-depth community-led “planning-action-reflection” process, Martín Peña leaders designed a whole new application of the CLT, using key elements from existing CLTs and devising others to serve the specific needs of their communities. Subsequently, these ideas traveled around the world, creating a movement of communities sharing lifeworld concerns. The example of the Caño Communities does not represent a “transfer process” of any “model” intended to “solve” problems. In narrating this success story, our aim is rather to prompt scholars, professionals and consultants to recognize the pivotal role that communities play in generating ideas that evolve into public policies capable of addressing situations and problems. Although quite different from the elite networks described by policy mobilities scholars mentioned in this article, in this grassroots movement we also clearly see that ideas mutate in the circulation process, and that global mobile ideas conglomerate with historical place effects.

Massey’s term of counterhegemonic policy mobilities has been useful to understand how these South-South circuits are challenging power relations. Communities are learning from each other to question the hegemonic worldview that prescribes individual forms of land ownership as the only viable path of development. We see this questioning and the ensuing creation of new applications (or the continuous protection) of collective forms of land tenure as “commons-based resistance” against the political, economic, and cultural world system and its perceived absolute institutions.

We have argued that, if we are to consider knowledge as true commons, all those who produce, use, and manage knowledge need to be included in the analysis. These communities are sharing ideas and influencing policy, and an explicit focus on their contributions to policy mobilities—at local and global levels—can help the development of more effective approaches to address the needs of the “urban poor” who will soon represent most of the world population.

This work is far from completed. The transnational networks and policy circuits described continue to develop. Recently, for example, a new initiative was launched inside the CLT Center to support the circulation of knowledge and best practice on collective land tenure in Latin America and the Caribbean, which will be led by the Caño CLT and CatComm. To be continued.

Notes

[1] WH is a non-profit organization supporting innovation in housing policy and practice: https://world-habitat.org.

[2] Three activists founded the Brussels CLT after visiting Champlain Housing Trust in Burlington during a peer exchange organized by WH (De Pauw & de Santos, 2020).

[3] CatComm is an American/Brazilian NGO supporting Rio’s favelas since 2000 through empowerment, research, and advocacy at the intersection of community development, human rights, communications, and urban planning: https://catcomm.org.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the tireless struggles of thousands of residents of the Caño Martín Peña and their allies. The ideas that are presented in this article are generated by them, and therefore they deserve the credit. We specifically thank all those residents and staff at the Caño Martín Peña organizations that have taken the time to talk to us and share their ideas. We also particularly wish to thank Evelyn Quiñonez, Mario Nuñez Mercado, Lyvia Rodríguez Del Valle, Alejandro Cotté Morales, Theresa Williamson, Tarcyla Fidalgo Ribeiro, and Enrique Silva who all contributed to the study on the potential of Community Land Trusts in Informal Settlements for the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. The authors also wish to thank the reviewers for their knowledgeable feedback.

Funding Information

The first author is a researcher at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium, who funded the research that this article is based on. The second author is an Adjunct Professor at the Clinic for Community Economic Development of the Legal Assistance Clinic at the University of Puerto Rico School of Law. The Lincoln Institute of Land Policy also contributed funding to the research this article is based on.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.