1 Introduction: commons and imaginaries

The commons, and especially irrigators commons, have been the arena of much academic inquiry. Much of this literature has focused on trying to understand common-pool resource governance through the exploration of formal and informal rules, biophysical characteristics of resources and social-economic and cultural attributes of the community of users that is involved in the process (Ratajczyk et al., 2016; Smith, 2022; Van Laerhoven et al., 2020). However, in the commons literature less attention has been given to understanding how the established ‘social order’ in and among the commons is challenged, contested, and transformed (Baggio et al., 2016; Meinzen-Dick et al., 2022; van der Kooij et al., 2015). In this contribution we aim to expand our understanding of these processes of contestation through the notion of imaginaries which we define as aspirational visions and perspectives through which actors give meaning to how the social practices, institutions, technologies and nature, were, are and should be ordered (see also Asara, 2020; Hommes et al., 2022; Jasanoff, 2015). The notion of imaginaries draws on an understanding of the imagination as genuinely creative in social, material, and symbolic terms (Adams et al., 2015; Manosalvas et al., 2023). This notion of imaginaries implies the fundamental recognition of “—the fact that other social groups understand and act in the world differently from ‘us’ [and each other]” (Pickering, 2017). As such, as we detail in this paper, imaginaries are also fundamental to understand the shaping, ordering, breaking, and remaking of the commons.

By bringing in insights from academics that have taken a creative and critical view on different ontological understandings, we open up new perspectives to understand the commons. We do so departing from the notion of ontology as “a set of concepts and categories that help us to identify, assemble, order and explain particular entities: their nature and properties, the relations among the constituting parts, and the relationships that give them substance and meaning in their contexts” (Boelens et al., 2022: 12). Based on this notion, we propose taking different and often plural understandings of objects, subjects, and relations seriously to better understand the commons. This is achieved by broadening our understanding of the divergent and plural cultural, social, productive, and ecological horizons in which commons evolve. Doing so is a means to innovatively analyze how and why the commons are sustained, re-created, and transformed (e.g., Hoogesteger, 2015; Smith, 2022; Aubriot, 2022).

We ground this contention by studying the role of imaginaries in the transformation of farmer managed irrigation systems in the context of the introduction of drip irrigation. To do so we first set out the dominant social imaginary that has been built internationally (and adopted by many national discourses and policies) around the technology of drip irrigation. Then, based on case study material, we analyze in detail two ‘dissident’ imaginaries of alternative irrigation assemblages that seriously challenge the ‘dominant drip irrigation imaginary’. These alternative imaginaries, we argue, assemble irrigation in a very different way than the dominant social imaginary -and in doing so-, open space for the critique of existing social practices. At the same time, these dissident imaginaries stand at the cradle of social change, transformation, and the advancement of an alternative future.

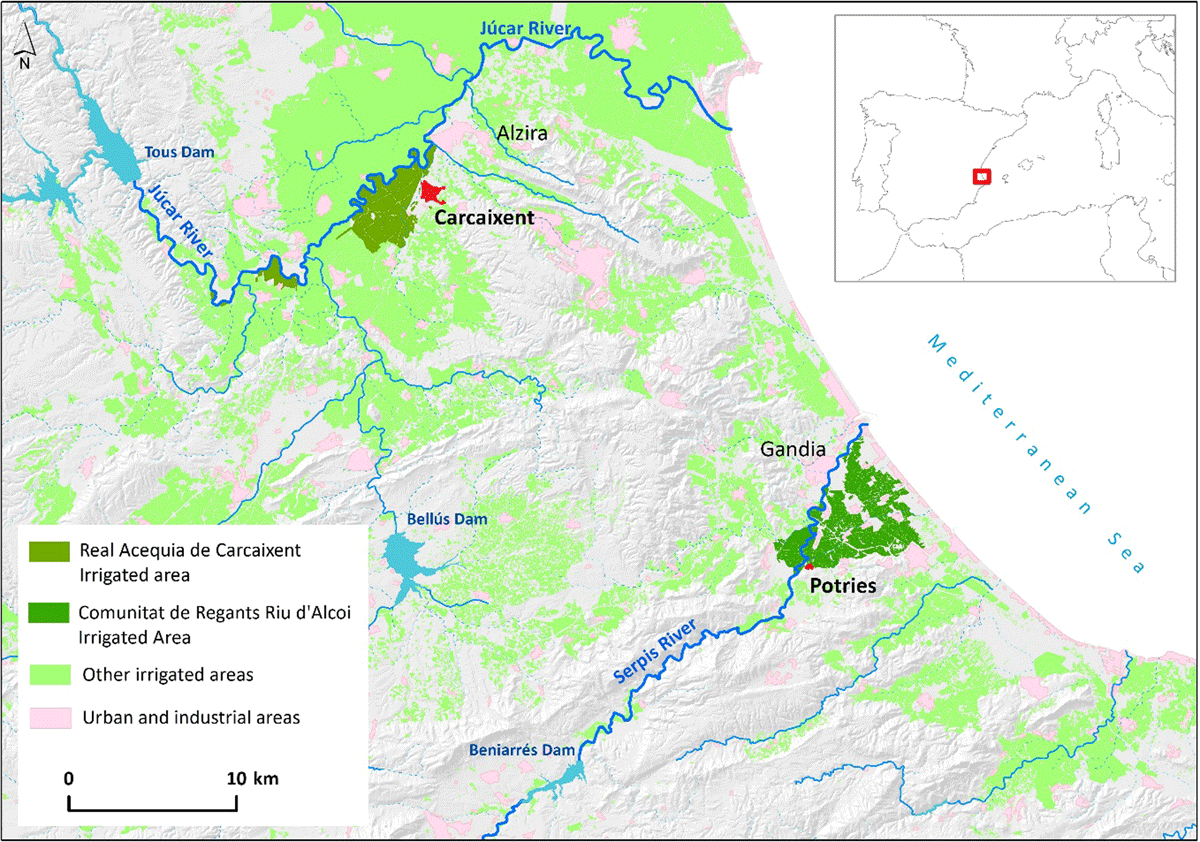

Our analysis is based on the case studies of the irrigation communities of Carcaixent and Potries in the Valencia region, Spain (Figure 1). The two case studies are located in the traditional citriculture gardens of the region. The small size of the landholdings, the advanced age of the farmers, and sometimes mixed cropping patterns besides citrus, characterize this historical agricultural system. The income from production has been decreasing due to increased market competition over the last decades (García-Mollá et al., 2014). Professional part-time farming has become a majority phenomenon, and hobby farming has also increased.

Figure 1

Sketch of location of Carcaixent and Potries study cases.

Data of the case studies that inform our analysis were collected through semi-structured interviews in the two case study areas during the spring and summer of 2018, with follow-up data collection in winter 2018-2019 and spring-summer 2022. For the case of Potries, in June 2018 we interviewed 7 farmers; 2 functionaries of the municipality of Potries; the mayor of Potries; the president of the government board of the Community of Irrigators of the Alcoi River; the operations manager and a technician of the same system; an environmentalist from Potries; the president of Fundació Assut; and assisted to a two-day regional seminar (15–16 of June) on traditional irrigation in the region, which was held in Potries. In June 2022, a follow-up interview was held with the mayor of Potries. For the case of Carcaixent, several interviews were held with the president of the irrigation community of Carcaixent in 2018, 2019 and 2022. In June 2018, interviews were held with 17 farmers (organic and conventional); the administrative staff of the irrigation community; and two water guards. Also in June 2018, we attended the General Assembly of the Community of Irrigators of Carcaixent, in which a long debate took place between the governing board of the community and about 200 irrigators. In the period January to May 2022, 11 interviews were held with organic citrus farmers and several informal encounters and discussions were held in the field with conventional farmers. Participant observation in the field as well as in several meetings, debates, and seminars on the topic during the research period have served to put the two cases in context of the broader debates that exist about the topic in the region. The analysis of the data followed a grounded inductive approach emerging from the interpretation of the collected empirical data. This initial analysis was sharpened, informed, and further developed by anchoring it in the theoretical insights that the notion of imaginaries brings. Finally, this was related to debates of the commons as elaborated in the next section.

2 imaginaries and the transformation of the commons

2.1 Imaginaries as assemblages

The notion of imaginaries points to the different ways there are of understanding and giving meaning to the world. As Adams et al. (2015) point out this enables the (re)production and transformation of social practices and institutions. Imaginaries give meaning to practices, institutions and networks that tie society (and commons) together (Castoriadis 2007). Through imaginaries, individuals and groups are able to take distance from day-to-day reality, enabling the creation and socialization of the not yet real (Castoriadis, 1975). From this perspective imaginaries are considered as the worldviews (time-bound perspectives and aspirational visions) that actors have about how the world, was, is, and should be ordered (Hommes et al., 2022; Manosalvas et al., 2023). Such imaginaries are based on social practices, institutions and socio-natural relations that give meaning to the past, the present and its development(s) towards the future – “imaginaries can be understood as the socioenvironmental world views and aspirations held by particular [individuals or] social groups, as the wished-for patterning of the material and ecological territorial worlds with and through the corresponding values, symbols, norms, institutions and social relationships” (Boelens et al., 2016, p.7). Steger and Paul (2013, p.23) further state that “imaginaries are patterned convocations of the social whole. These deep-seated modes of understanding provide largely pre-reflexive parameters within which people imagine their social existence.” Sheila Jasanoff further elaborates on the intrinsic relations between the social and the technical when she defines sociotechnical imaginaries as “collectively held, institutionally stabilized, and publicly performed visions of desirable futures, animated by shared understandings of forms of social life and social order attainable through, and supportive of, advances in science and technology” (Jasanoff, 2015, p. 4). Also in the arenas of hydro-social configuration, imaginaries are constituted as understandings of the present and the desired futures that individuals or groups have about how the social, the natural and the technical are, should or could be ordered (Hommes and Boelens, 2018; Hidalgo-Bastidas et al., 2018).

To study diverse and divergent imaginaries we turn to debates about ontology (Mol, 2002; 2008). The recognition of different ontologies allows us to recognize that there are multiple ways of knowing, understanding, and acting on the world we live in. This recognition gives room to concepts, ideas, knowledges and realities “that commonly are thought to be unproblematic and univocal” (Reyes Escate et al., 2022), creating ‘openings’ (De la Cadena, 2017) for ‘human-nonhuman networked realities’, such as irrigation, production, institutions and technology, to be more and/or different from what they already are in the mainstream/dominant sense. From this perspective imaginaries, which represent a specific way of knowing and understanding the world and how in it social and natural elements tie together as -and through- relations, are plural and dynamic (Hoogesteger et al., 2016; Yates et al., 2017). They tie heterogeneous elements (objects and subjects) together differently and with ‘other meanings’ creating alternative relations and compositions which we understand here through the notion of assemblages. As put by Deleuze an assemblage is: “…a multiplicity which is made up of many heterogeneous terms and which establishes liaisons, relations between […] different natures. Thus, the assemblage’s only unity is that of a co-functioning: it is a symbiosis” (Deleuze & Parnet, 1987: 69). It is a symbiosis in which elements do not stand on their own but are part-of and interwoven with other elements. The latter exist, can be explained, and understood only in the multiplicity of relations that are created through and around it. Therefore ‘things’ (objects & subjects) are intrinsically relational, networked and context specific; there is no object or subject that exists outside of the relations it has with others. It follows that assemblages of objects and subjects can only be known, understood and acquire meaning through their historical onto-epistemological and cultural-political positioning and ‘situatedness’ (Haraway, 1988). This creates space to understand commons and the different imaginaries that emerge around them “from the perspective of actors and stakeholders engaged with, relating to, and living with it from day to day” (Reyes Escate et al., 2022).

2.2 Alternative imaginaries as seeds of social change

To better understand the contestations that emerge around different imaginaries we divide these in socially prevailing (or dominant) imaginaries and alternative imaginaries (both sidelined, less influential, and not yet existing)(Asara, 2020). According to Taylor (2004) socially prevailing imaginaries refer to how people imagine and live their social existence around built expectations and their underlying normative notions which Castoriadis (1975) termed the ‘enslavement of men to their imaginary creations’. However according to this same author this enslavement and normalized existence can be challenged by groups of individuals that critique the instituted society by (re)creating alternative imaginaries (Asara, 2020) along with challenging existing socio-economic property structures and power relations (Van der Ploeg, 2012). This is done by developing a critical distance between the dominant social imaginary and ‘the horizon of potential otherness’ that constitutes as the ‘germ’ of transformation through autonomy from the dominant social imaginary and related order (Castoriadis, 1997). From this perspective, social change results from the slow process of transformation in social imaginaries, material property relations and epistemological belief systems. The infiltration of new socio-material practices are developed among alternative/divergent strata of society (Adams et al., 2015; Hoogesteger and Verzijl, 2015).

The infiltration of these practices is based on alternative imaginaries that develop in and through networks and social struggles that enable basic redistribution of the materialities and means of existence while imagining life and social institutions not as they currently exist, but bringing new socio-material worlds into being (Escobar, 2020). This grounds in, and challenges, existing socio-material realities (Haiven and Khasnabish, 2014). This also happens in the case of the commons, through the reinterpretation, resignification and re-assembling of social practices, networks, institutions and the natural and built environment. Herein alternative imaginaries unfold as a reaction, for instance to commodification, privatization and other de-commoning processes (Hommes et al., 2022). In fact, as Boelens et al. (2022: 8) observe, “commoning refers to the practices of place- and community-making as a radical alternative to commodification, which establishes exclusive property relations and universally exchangeable, market-transferable goods”. Based on alternative imaginaries actors act to (re)shape their reality through (1) discourses, (2) networks, and (3) material practices that challenge the dominant social imaginaries (Hulshof and Vos, 2016). This process thereby challenges the often mentioned or implicitly deployed notion of an ‘objective’, ‘measurable’, and uniformly knowledgeable reality; a perspective that has dominated many of the frameworks used for the study and analysis of the commons such as the socio-ecological-systems framework (SES) (see Ostrom, 2009; McGinnis and Ostrom, 2014) and the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework (IAD)(McGinnis, 2011; Ostrom 1990). These approaches have been criticized for their ahistorical and apolitical approach as well as a narrow definition of economic and resource related interest (Mosse 1997)(for its elaborations and some fundamental critiques, see for instance Duarte-Abadía & Boelens, 2016; Hoogesteger et al., 2023; Whaley, 2018, 2022; Vos et al., 2020).

Based on the notions discussed above, in the next section, we present the dominant mainstream social imaginary of irrigation modernization through drip, focusing especially on Spain. In the sections that follow we analyze two alternative imaginaries that have emerged around drip. These alternative imaginaries illustrate how irrigation is assembled otherwise, tying very different elements and relations together in and around the same objects and irrigation processes.

3 Dominant imaginaries of drip and its discontents in Spain

Drip irrigation has been presented for decades as a silver bullet to increase water use efficiency and productivity in irrigation while opening opportunities to reallocate the saved water to other uses or users by both engineers and politicians (Van der Kooij et al., 2013; Venot et al., 2017). International organizations and national governments have encouraged policies that promote or subsidize drip installation on a large-scale for decades (Venot et al., 2014), embedding these policies in a discourse of progress and modernity (Boelens and Vos, 2012; van der Kooij et al., 2015). In this discourse, irrigation is assembled mainly in terms of a context of water scarcity and competition. In this context, irrigation is to be modernized to save water and produce more crop per drop (Damonte & Boelens, 2019; Kuper et al., 2017, Molle et al., 2019). In this assemblage, farmers are imagined as modern, rational, competitive entrepreneurs who aim to ‘save water’ and maximize production through the use of the latest technologies (Hoogendam, 2019; Vos and Boelens, 2014; Venot, 2017).

Spain has fervently promoted the modernization of irrigation towards drip and has the largest area of drip irrigation systems in the Mediterranean region. Since the cathartic drought of 1994–1995, different public administrations have promoted the installation of this technique in the semi-arid regions of the country through consecutive support plans and financial instruments (Naranjo, 2010; Sanchis-Ibor et al., 2016). Apart from the goal of decreasing overall water use in agriculture with 3000 million cubic meters (Mm3) per year, the objective of this policy was to increase the competitiveness of farmers and to prepare for the liberalization of the market and a lowering of subsidies in the context of the Common Agricultural Policy reforms of the EU (Lecina et al., 2010). Agricultural productivity, competitive employment in agriculture and improvement of the quality of life in rural areas were also considered as positive outcomes in the policy documents (Playán & Mateos, 2006). The urge to implement this technology in the country has been strong (López-Gunn et al., 2012a), and drip irrigation has been widely discussed among farmers (Ortega-Reig et al., 2017). As a result, the area under drip irrigation has grown over the last two decades to 2.1 million hectares (Mha), 54.58% of the total irrigated land, while traditional gravity irrigation is only preserved in 0.8 Mha (22.3%) (ESYRCE, 2021). However, the sometimes disappointing results of the application of these technologies (Dumont et al., 2013; López-Gunn et al., 2012b) and, above all, the recent change in the irrigation efficiency paradigm (Perry and Steduto, 2017; Grafton et al. 2018; Ward and Pulido, 2008) have led to a new scenario.

The dominant imaginary was built, at the end of the last century, around the (expected) water-saving potential of this technology and its ability to improve crop productivity. This argument has recently been renewed, incorporating two powerful and emerging discursive elements in the Spanish context: climate change and the depopulation of rural areas (FNCA, 2021). Due to its (hypothetical) capacity to save water and improve production, pressurized irrigation is expected to meet these challenges. These discursive elements have been sustained by the elites of the agrarian organizations and the leaders of the irrigation entities. However, many irrigators have had little decision-making influence in this process. A large majority of the producers have valued productivity increases, labor and cost savings more than possible water savings (Ortega-Reig et al., 2017; Poblador et al., 2021).

The questioning of this dominant imaginary was restricted to academia until the publication of a WWF report in 2015 (WWF, 2015; González-Cebollada, 2018). Critical notes about this dominant imaginary have also been issued in different documents and discourse by the European Union, non-governmental organizations and civil society. In Spain, research has evidenced the scarce water saving capacity of this technological shift at basin level; while also pointing to the possible increase in irrigated areas and related rise in water demand; also known as the rebound effect (Berbel et al., 2015; Corominas and Cuevas, 2017; Ruiz-Rodríguez, 2017; Pool et al., 2021; Sampedro-Sánchez, 2022; Ros et al., 2022).

Agricultural organizations have responded with other works (Gutiérrez-Martín & Montilla-López, 2018), in defense of the dominant imaginary. However, many farmers and irrigation system collectives that maintain traditional networks are at least cautious about the possibility of introducing drip irrigation, if not outright rejecting it (Sanchis-Ibor et al., 2021). The different imaginaries associated with the future of agriculture -and the place of drip irrigation in it- are creating clashes among its potential users (Martínez, 2013; Sese-Minguez et al., 2017; Poblador et al., 2022), but have so far received little attention in academic debates on user/farmer-managed irrigation systems. This new imaginary is largely based on the emerging vindication of the cultural and environmental values of traditional gravity irrigation (Albizua et al., 2019; Martínez-Paz et al., 2019). In different regions, local commons organizations have been created to defend the historical irrigation heritage (natural and cultural), involving also the preservation of gravity irrigation lands, devices and practices (such as Salvemos la Vega in Granada; Per l’Horta in Valencia; Huermur in Murcia; and Intervegas as national association). Moreover, in those territories where centralized fertigation has been imposed, resistance is led by those who practice organic agriculture, because their tasks are hampered by the compulsory use of synthetic fertilizers in community pipeline networks (Poblador & Sanchis-Ibor, 2022).

One of the regions where differences between opponents and proponents of drip irrigation become apparent is Valencia (see also Sanchis-Ibor et al., 2021). Here, gravity irrigation has already been replaced for drip in a large part of the irrigation sector (211.827 ha, 73% of the irrigated lands; ESYRCE, 2021). However, for many stakeholders especially in the historical surface water irrigation communities, the switch to pressurized irrigation systems to enable drip-irrigation at field level is not a self-evident given. As explored below for two case studies, this is closely tied to different imaginaries about irrigation and how it assembles productively and as a socio-cultural and environmental element and process in the landscape.

4 Real Acequia de Carcaixent: Re-creating an alternative productive irrigation assemblage

The farmer managed irrigation system of Carcaixent (see Figure 1) supplies 1,800 hectares (ha) with irrigation on around 4,000 plots that are owned by about 1,800 producers. Its current canal system, originating from 1654, is administered, maintained and operated by a local irrigation community: The Real Acequia de Carcaixent. In the 1940s, under the regime of Franco, Carcaixent joined the Unidad Sindical de Usuarios del Júcar (USUJ) together with five other irrigation communities and a hydropower company (Iberdrola). This organization was created to finance the construction of the Alarcon Dam (1,100 Mm3), that now regulates (together with other dams that were built later) the flows of the Júcar River for its use for irrigation and hydropower production. The Alarcon Dam was the only privately owned large reservoir in Spain. However, in 2001, the government of Spain agreed to fully subsidize the modernization of irrigation (conversion to drip) in the USUJ area in exchange for the transference to state management and ownership of the Alarcon Dam. Following this agreement, the process of modernization to drip irrigation at the system level began in two neighboring irrigation communities of Carcaixent, namely the Acequia Real del Júcar and the Real Acequia de Escalona (García-Mollá et al., 2020).

In line with the agreement and the developments in the neighboring irrigation communities, around 2014-2015 the board of the irrigation community of Carcaixent prepared and signed contracts for the first technical studies for modernization to drip. These would form the basis for the later construction works to pressurize the whole irrigation systems. However, irregularities in the procedures led to conflicts within the irrigation community; and the subsequent election of a new board in 2017. The latter stalled the project and started legal investigations on the procedures followed by the previous board. Alongside these actions, the new board has re-opened the debate on whether, and under which conditions, drip irrigation is desirable for Carcaixent; a debate that is based on different imaginaries of irrigation and how it assembles.

A large group of producers shares the dominant imaginary that has been created around drip; albeit with the underlying concern about the costs of installation each user is assumed to incur. There is also a group that has a different vision of irrigation as expressed by a board member of the Real Acequia de Carcaixent: “Firstly, the roots of trees grow a lot deeper; the plants are therefore more resilient in cases of drought. Secondly, the irrigation water serves to recharge aquifers (with clean water from organic fields) that serve other people and nature in downstream regions. Thirdly, the natural resting period of the orange in winter is maintained, which keeps trees healthy and saves water and finally, the irrigation system is run by knowledgeable people, which makes the system efficient in water use and creates rural labor.”

For this group of producers, the surface canals in Carcaixent have important heritage value and are, therefore, not only appreciated by the farmers but also viewed as cultural history. This is the case since orange production and surface irrigation formed the basis for the establishment of the town of Carcaixent. Almost all the farmers mentioned that protecting their agricultural heritage is a chief reason to continue cultivating their field with surface irrigation. Finally, the low cost of surface irrigation makes the technology attractive while also promoting social interaction after working on the fields, and job creation for the operators.

However, for most farmers the bigger concern in the irrigation assemblage is that of the profitability of production. Put in the words of the Mayor of Carcaixent: “In Carcaixent, we are worried in general, but the worries are not so much related to irrigation. They relate to the current crisis for citrus tree producers.” The low prices of oranges and the rising costs of agricultural inputs make it very hard for producers to make a profit or in some cases even cover the production process costs. In this context, some farmers envision drip irrigation as the means to become competitive in the market. These producers highlight that drip irrigation is better for production and requires less labor for fertilizing, irrigating, and weeding, which makes hiring laborers superfluous and reduces production costs. They argue that irrigating becomes more comfortable because the presence of the producers on the field to irrigate and fertilize is reduced. This reduction in labor is the result of the centralization and externalization of irrigation and fertilization in the field which is now often done by the water users community technical staff through the automated pressurized conduction system (see also Ortega-Reig et al., 2017; Poblador et al., 2021). This is usually done through centralized irrigation and fertigation modules that are controlled by the irrigation communities’ staff. This is especially attractive for part-time producers that combine production with off-farm jobs. In this imaginary, producers see themselves as part of the larger process of modernization and globalization of agriculture.

However, there is a small networked group of organic farmers that have very different imaginaries of irrigation and how it could or should assemble. These producers envision production and producers very differently as put by a member of a local cooperative: “With La Vall de la Casella we strive to have an all-year round vegetation cover, Mediterranean hedges and natural organic control of pests and fertility. Also, the integration of animals and beneficial plants are stimulated. Furthermore, we aim for the least possible use of machines and promote solar energy use and therefore reduce the use of fossil fuels. The prices we pay to the producers and workers is fair, which is also an important value in the cooperative.”

For these farmers the quality of the production process, the products and the relation with the customers is very important. Therefore, all these producers have certified their plots as organic. As expressed by one of the producers: “Some of my clients do want the certification, because they want to be ensured the product is free of chemicals, although I have personal contact with every one of my clients, only my word is not enough”. Aside from the organic certification, these producers stress the value of an artisanal way of production and the denomination of origin of the produce. The knowledge and experience of the producers’ results, they say, in a high-quality product with a high sweetness and juiciness. The use of ‘traditional’ varieties that do well in the local environmentis an important characteristic of their production process. The optimum timing of the harvest and quick shipping to the (local and regional) costumer through direct sale or the cooperative, is important in this assemblage. It ensures that the fruit is as fresh as possible when arriving at the homes of their clients while also generating a higher income for the producers. Producers are proud of their production process and the products they sell, making them distinct from fruits from conventional production. Some of them also link their production to their contact with and the experience of their customers: “The people that buy our fruit do not only buy the fruits, but as well the story of our artisan way of producing. When they buy our fruits, they can come and visit our farm to spend the day have a meal and even sleep on the farm”. Therefore, several ‘alternative’ sales channels have been created by these producers through personal networks, producers’ cooperatives and the direct sale on internet.

This group of producers that has an alternative irrigation imaginary has over the last five years opened up many discussions within the irrigation communities to question and ‘re-think’ the necessity of modernizing the whole irrigation system to drip. Over the period of analysis, we evidenced a slight shift in the ‘alternative’ imaginary. It has transitioned from a purely ‘against drip’ imaginary to one in which there are openings for the compatibility of drip irrigation with organic production. At the same time this imaginary has opened the possibility to adapt to the functioning of the irrigation system to accommodate for farmers that want to install and use drip. As one of the ways to move forward, the irrigation community has adapted the management of the water levels in the system to enable users to install pumps to pressurize water from the canals to use drip with an adapted irrigation schedule. The irrigation system as a whole has become a hybrid that accommodates different productive irrigation assemblages and the imaginaries that inspire and support them (see also Sanchis-Ibor et al., 2017a, b). If and how the irrigation system as a whole and producers individually switch to drip irrigation will greatly depend on which irrigation imaginaries become dominant within the irrigation communities, how these are sustained by socio-economic relationships and techno-political power structures, and on whether and how these materialities and imaginaries are contested and negotiated by different or opposing groups. For now, the group that defends an alternative imaginary that challenges the universality of the benefits of drip irrigation has been able to stall the full modernization of the irrigation system; while still offering alternatives to the users that do want to use drip on their fields.

5 Potries: “The future happens by taking a step backwards”

The community of Potries1 is located in the Gandia region of southeastern Spain and hosts just over a thousand inhabitants. The farming community relies on the Alcoi River (also called Serpis) for irrigation water and has done so since the construction of irrigation systems by the Moors (7th to 13th century). The crops mostly cultivated are citrus varieties in so-called huertas (horticulture gardens). Although citrus is emblematic to this region, some farmers also diversify their cropping systems to include other fruit trees and vegetables. The management of irrigation systems within the historical Gandia huerta system is presently headed by the Community of Irrigators of the Alcoi River. This institution oversees the irrigated lands of Potries and 15 other municipalities, covering 2,147 hectares. When the river water is insufficient, farmers pump groundwater to complement their irrigation turns.

Potries municipality is located furthest upstream in the Community of Irrigators of the Alcoi River. Here, an intake weir diverts water from the Alcoi River to all downstream municipalities. The location of the weir along with two ancient Moorish water division structures, namely Casa Clara and Casa Fosca, make Potries signatory to the historical huerta system. These iconic diversion weirs enabled the division of water that was supplied further downstream to the irrigated fields in other municipalities.

Since 1999, the irrigation infrastructure has been modernized and pressurized for the installation of drip irrigation at field level with the support of regional and EU funding. Between 2010 and 2013, four cabezales (drip irrigation hydrants) were built by the company OCIDE-CYCA. After the installation of these cabezales, water in Potries is treated and fertigated before being pumped to the field intakes (hydrants). Farmers can subsequently connect their own drip lines to the hydrants. Though this infrastructure was in place, many farmers still irrigated by flooding their field through the use of the ‘traditional’ infrastructure that has been used for centuries. To put an end to this, in March 2017, the general assembly of the Community of Irrigators of the Alcoi River decided to prohibit surface irrigation and seal off the historical infrastructure by January 2019. This was done arguing that the traditional infrastructure and related irrigation practices were inefficient and outdated; and that operational costs of the irrigation communities could be reduced by closing off the ‘old’ infrastructure. This decision was taken based on an imaginary of irrigation as a productive activity that should be ‘rationalized’, and managed efficiently to ‘save water’ and ‘produce more crop per drop’.

The decision to close off the traditional infrastructure ignited a heated political debate in Potries, where a large group of actors have an imaginary of irrigation that assembles it very differently. It places irrigation not only as a productive assemblage but assembles it as part of a broader social cultural heritage and riverine landscape. The traditional irrigation infrastructure, and especially the division structures Casa Clara and Casa Fosca (see Figure 2) are seen as fundamental cornerstones of the geographical, cultural and historical importance of Potries. Maintaining these structures and related canals functioning is seen as guarding and re-creating an important cultural and historical value of the area. As expressed by a villager: “How is it possible that a system that was giving life to a community and that belongs to our way of living and understanding, is replaced by a system that brought us high debts and many social and environmental problems, is this progress? If this is progress, I would rather live in Moorish times.”

The mayor of Potries, underlines the social significance of the infrastructure: “People had to come together to decide upon water division”. Water division was agreed upon during the weekly-organized meetings with water user representatives and adjusted accordingly. She argues that Potries stands as a symbol for water cooperation and is the very last stronghold that maintains shared irrigation practices within the Community of Irrigators of the Alcoi River. The ancient open canal infrastructure keeps the rich history alive, but also holds contemporary value in that it has the potential to bring people together. The increased distance between top-management and farmers in the Community of Irrigators of the Alcoi River has implications for the day-to-day use of water. As put by an irrigator: “If you want more water - you have to go to Gandia. It used to be – just go to the bar and talk with each other. Now bureaucracy has the overhand.” As one farmer puts it: “Since the change to drip, I never went to a meeting anymore. The communication is very bad.”

At the same time, the open-canal infrastructure has an important value for all the villagers of Potries. The municipal council created and promoted a walking route -Ruta de l’Aigua- along the traditional infrastructure and irrigated field of Potries (see Figure 2). It highlights the historical and cultural value of the canal system and the flow of water. The irrigation canals have also served as spaces of refreshment, leisure and recreation for generations. The town’s mayor is proud that generations of villagers of Potries have learned to swim in these ancient irrigation canals and posits that this is part of their culture and identity just as the water that flows through these open traditional irrigation systems. As expressed poetically by a villager: “When you hear the water flowing through the village, your spirit opens.”

Figure 2

Map of the Ruta de l’Aigua indicating the main historical infrastructures in an idyllic representation (top). Casa Clara (bottom left) and Casa Fosca (bottom right) ancient dividers. Source: Turisme de Potries.

The canal infrastructure also assembles as an important element of the local environment and biodiversity. A local environmentalist argues that endangered fish species survive periods of drought by residing in the main canals and that the system has become part of the biodiversity system of the Alcoi River: “The system is important, these dynamics will not continue when the infrastructure is neglected and crumbles away”. Furthermore, traditional surface irrigation is said to result in lusher vegetation, thriving ecosystems and richer fruit-bearing trees than with drip irrigation.

The campaign within Potries that questions the current transition to drip and promotes the cultural importance of surface irrigation systems is led by Potries’ mayor. According to her, the election of Potries as cultural capital of the Valencian region (2018–2019) was of utmost importance to recognize the cultural value of ‘traditional irrigation’: “Having Potries as cultural capital is part of the plan for getting the message across.” In her actions she defends her imaginary: maintaining a water flow through the canals, especially in the stretch of la Ruta de l’Aigua: “It is the fight for an identity. It is the fight for a territory. It is not just economic aspects. We were born here. We don’t want it to change.” Moreover, to convey her message, she organized a conference on Valencian horticultural heritage in Potries; an art exhibition in the municipal hall about la Ruta de l’Aigua; and a meeting in Brussels with a Member of the European Parliament.

Another important aspect of this alternative irrigation assemblage is that of the commons. While classically the irrigating commoners constitute an irrigation community and shape its ‘commons’, in this alternative assemblage the commoners are expanded to all the common villagers of Potries as well as to visitors and tourists – in direct relation with the flora and fauna ecologies that entwine with the waterflow system. The people who vocalize these integrated socio-ecological commons, at this moment, have no say nor vote in the Community of Irrigators of the Alcoi River. The mayor of Potries reflects: “People from Potries are not represented in the community [of irrigators].” The cultural and socio-ecological value that landless inhabitants of Potries (youth, environmentalists, tourists) might attach to the canals, stirs little sympathy in the Community of Irrigators. Their network is seemingly extensive but remains without much influence. Even when municipal office workers state that the tourism industry has been growing, the main attraction being La Ruta de l’Aigua, its cultural and ecological value is only partially considered by the Community of Irrigators.

The active players in favor of keeping the surface irrigation infrastructure in use are, like those that promote drip, not confined to the geographical borders of Potries. NGO’s, such as Fundació Assut, underscore the socio-historical heritage of this system and agree with the municipality regarding the diversity of uses to the system. Its president has expressed special concern over the adoption of drip irrigation: “Technology that comes, rises above the farmers and gains power”. As the experiences of several other irrigation communities in Spain have shown (e.g. Sanchis-Ibor et al., 2017a, b; Duarte-Abadía et al., 2019; Villamayor-Tomas and García-López, 2021), the network of actors that value cultural and socio-ecological heritage seems to be growing over the years. This has important consequences on the debates there are at different scales about what the future of these irrigation systems and their commons should be. In this context, Potries is increasingly symbolized as another stronghold to guard against the full modernization of farmer managedirrigation systems.

6 Conclusions: imaginaries and the trans-formation of the commons

In this contribution we have analyzed the different imaginaries that emerged around the introduction of drip irrigation in Spain. We have done so by conceptualizing imaginaries as assemblages that tie different elements together through their situated co-functioning and symbiosis (Haraway, 1988). We show how through imaginaries, social practices and institutions are given meaning and reproduced but also and importantly challenged and transformed. Here, socially overarching, dominant imaginaries and alternative imaginaries collide and confront each other.

As the study shows, the now “dominant imaginary” of drip irrigation has over the past two decades changed traditional irrigation practices and related economic, social and environmental relations. These changes have by and large been labelled by dominant actors as socially, economically and ecologically desirable and beneficial. Nonetheless, it has elicited the emergence of ‘new’, ‘hybrid’ and/or the revival of ‘old’ alternative imaginaries that question the benefits of drip and advocate for the conservation of traditional practices; and/or the combination of drip with traditional practices through the advancement of hybrid compositions. The latter creatively combine elements of both old and new, dominant and alternative imaginaries. We have analyzed the formation of these hybrids in Carcaixent, but we have also been able to observe these same solutions in many other traditional Spanish irrigated areas (e.g. Sanchis-Ibor et al, 2017b, 2021).

Examining the dominant imaginaries that have developed internationally and in Spain around drip irrigation technology, we see how these revolve around a very specific rationality about water savings and efficiency, modernization rationality, market-based productivity, competitiveness, and progress characterized by labor savings, technification and entrepreneurship. Many of the underlying assumptions are conceptualized as favorable for the re-creation of institutions for collective action in the SES and IAD frameworks.

The study of alternative imaginaries amongst the commons challenges this notion by recognizing the importance of social relations, cultural, ecological and symbolic values. It shows, first of all, that values, rationalities and how people live and relate to their commons and related institutions (in this case irrigation systems and communities) is not universal but plural. This plurality embraces values that are often not taken into account in studies and understandings of farmer managed irrigation and common pool resource governance. The plurality of often unrecognized values includes, as the case studies show, cultural (practices and heritage) value, aesthetics, a sense of place and belonging, the valuation of specific forms and practices of production, the maintenance of environmental values related to the irrigation system and the existence of places of social encounter and socio-ecological conviviality, amongst others (see also Mirhanoğlu et al., 2023, this issue).

Our case studies also show that the existing notion of the ‘commons’ defined as the common pool resource users is often not accurate. It points to the need to expand our analysis to include other forms of ‘common entities, properties and modes of sharing’ such as rights of free passage (walking routes), and culturally valued spaces that are used not only by the resource users. Spaces that are used by a much broader group of actors for other than productive use (such as for instance swimming and recreation). This also applies to cultural commons such as knowledge and practices as exemplified by traditional orange production practices as well as to rituals and cultural assets, even though these were not identified in this specific study (but see Manosalvas et al., 2021). Next, importantly, the notion needs to recognize the neat entwinement of human and ecological (nonhuman) communities in making and re-making commons. In that sense, we align with the idea of socionature commons as defined by Boelens et al. (2022:8): “networked socio-ecological arrangements that embrace and mobilize the social and the natural – human and non-human – and practice […] stewardship based on their mutual interdependence on shared […] livelihood interests, knowledge and values”. In fact, what we observe is that traditional irrigation systems acquire in contemporary societies additional values to those that motivated their design. They present, today, a multifunctionality that has been widely recognized in many agrarian systems (Ricart and Gandolfi, 2017), but which is not fully acknowledged by existing collective action institutions. The latter often focus on and prioritize the agricultural use of water. It is this mismatch which, to a large extent, explains and fuels the coexistence of divergent imaginaries. Moreover, it is also the germ of conflicts such as those analyzed in this case, or of dilemmas arising in other similar spaces (Llausàs et al., 2020; Mirhanoğlu et al., 2022; 2023).

In that sense there is no ‘single or same’ irrigation system, rather we are confronted by a plural system that is assembled and thus understood and acted upon differently by different individuals, groups and socio-ecologies. These differences in imaginaries lead to actions and contestations that give form to how these commons and their irrigation systems are being reproduced and transformed; a phenomenon that is rather poorly studied and conceptualized in the literature that has built on institutional analysis frameworks to investigate common pool resource governance. Therefore, the study of imaginaries opens up new fields of inquiry into the commons, and farmer-managed irrigation systems more specifically. It allows us to take the different worldviews and realities that exist within and among the collectives that share, use and govern common resources seriously. It becomes a means to better understand the source of the conflicts and negotiations through which practices, relations, networks, institutions and technologies are either reproduced, challenged or transformed among the commons.

Notes

Funding information

This research was partly funded by the River Commons project (INREF-2020), the Riverhood project (ERC, EU-Horizon2020, grant no. 101002921), see (https://movingrivers.org/) and ADAPTAMED (RTI2018-101483-B-I00), funded by the Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad (MINECO) of Spain and with EU FEDER funds.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.