1. Introduction

The governance of agriculture water for equitable and effective management is a crucial task for meeting global food security and achieving UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly for small-scale farmers in Global South (Pahl-Wostl, 2019; Di Vaio et al., 2021). Currently, most research across the world has revealed that resource conflict is a key issue for small-scale farmers in negotiating water access, which generally results from water scarcity, increased water use, the introduction of cash crops, unclear property rights arrangements, inadequate water infrastructure, state interventions, and the breakdown of traditional practices (e.g., Anand, 2007, Benyei et al. 2022, Crow and Sultana, 2002, Chowdhury & Behera 2021, Mukheibir, 2010, Peloso and Morinville, 2014, Zwarteveen and Meinzen-Dick, 2001, Wang et al. 2009). Other research has indicated that downwards accountability mechanisms, decentralized use rights, recognition of customary institutions, and secure property rights can lead to positive outcomes in water governance for smallholders (e.g. Mwihaki, 2018, Wilder and Lankao, 2006, Smith 2022). Thus, there is a need to advance the understanding of how institutions can be established and operate for water management to ensure effectiveness and equity.

For the theory of institutionalism, the most influential scholarship has originated from Ostrom’s school of thought, which generally advanced institutionalism to analyze how institutions (both legal and practical) were developed to form a collective action for sustainable resource management (Ostrom 1990, Ostrom et al. 2003). Furthermore, the “Eight Design Principles” (DPs) were developed to serve as golden rules for institutional development.1 Ostrom’s Eight DPs were influential not only in academic research but also in practice, guiding decades of action-research for development programs, agencies and donors worldwide under Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) (e.g., Agrawal and Gibson, 1999, Leach et al. 1999, Agrawal, 2001, Fabricius and Collins, 2007, Gruber, 2010). The CBNRM has adopted the Eight DPs for small homogenous groups with clear boundaries and precisely measurable geographic units characterized by local decentralized participation (e.g., Agrawal, 1999, Blaikie 2006, Agrawal, 2001, He and Xu, 2017). However, some current research has argued the overgeneralized nature of the Eight DPs (e.g., Araral et al. 2019, He et al., 2021, Zang et al. 2019). Other literature suggests that the Eight DPs are rather static (e.g., Armitage, 2005, Baggio, et al. 2016, Chai and Zeng, 2018), asserting that a dynamic perspective is needed for the analysis of commons. Research has also attempted to supplement Ostrom’s work in the context of large groups and social heterogeneity (e.g., Araral et al. 2019, He et al., 2021, Wang et al., 2019), as implementing the ideal “Design Principle” seldom finds purchases in reality. While these efforts suggested the limitations of using DPs and attempts to enrich the theories, there is a lack of novel analytical frameworks for explaining commons in the context of complexity and dynamics.

This research goes a step further to wield an environmental justice approach to examine the governance of irrigation waters in the context of small-scale farmers in Southwest China. Focusing on water as the common-pool resource, this empirical research uses ethnographic fieldwork to examine water governance at the World Heritage-listed watershed Malizhai River Basin in Yunnan Province, China, where multiple ethnic groups have shared irrigation water for cultivating rice terraces for centuries. The Malizhai watershed and China in general do not map neatly onto existing DP theory; this is largely because many large and socially heterogenous groups live in the region, with unclear property rights to the water as well as weak decentralization and accountability. As a case study, the site could expand the robustness of Ostrom’s DPs, and thus, the research adopted an environmental justice conceptual framework to examine how the water is shared and governed for rice cultivation by different ethnic groups residing at upper, middle and lower levels of the watershed. By mapping multidimensional justice practices, i.e., distributive, procedural and recognitional, onto real-world examples, the research contributes a novel argument suggesting that commons (irrigation water in this case) can be well managed when different notions of justice are practiced by multiple stakeholders, enriching Ostrom’s scholarship and existing literature on the studies of commons. The empirical contribution of the paper calls for a wider understanding of plurality and the multidimensionality of justice practices situated in local value systems in China and beyond.

The paper is structured in five sections. In the next section, we present the analytical framework of the environmental justice approach, which followed by a description of the research methodology. The fourth section presents the local practice of justice in irrigation water from a multidimensional perspective, i.e. distributive, procedural and recognitional justice. Finally, the paper concludes with a discussion of the theoretical and empirical implications of the research.

2. Environmental justice framework for analysis

This research suggests to understand the commons from a lens of environmental justice. Environmental justice analysis is now increasingly widespread in environmental research to understand social justice for environmental management (Martinez-Alier 2003, Schlosberg 2004, Walker 2012, and Sikor et al. 2014). Scholars have revealed that environmental problems can result from social injustice, and in turn, environmental problems can also lead to social injustice (Sikor 2013, Martin, 2017, Coolsaet 2021). Given this entwined relationship between justice and environment, scholars have proposed that justice could function as an ethical consideration for society (e.g., Martin, et al. 2016, Lehmann et al. 2018) as well as be an instrumental approach for improving sustainability (e.g., Schreckenberg, et al., 2016, Zafra-calvo et al. 2020, He et al. 2021). More research is hinting that justice is a precondition for effective management in protected areas, payment for ecosystem services, community forestry as well as cross-scale governance of water and climate (Martin et al., 2014; He & Sikor, 2015; He et al. 2021, Fisher et al., 2018, Schlosberg & Collins, 2014; Schroeder & McDermott, 2014Zeitoun et al., 2014; Neal et al., 2014, He and Wang, 2023).

An empirical framework for environmental justice analysis consists of three dimensions (Martinez-Alier, 2003, Schlosberg, 2004, Walkers, 2012, Sikor et al. 2014): 1) Distribution: this indicates the equal distribution of costs and benefits associated with the environment (Schlosberg, 2004, Sikor 2013). Distributive justice is primary for environmental justice. 2) Procedure: this calls for processes to ensure that all parties have equal voices in negotiations (McDermott et al., 2013). It is reflected by indicators of participation, which ensure that stakeholders of a given environment have equal participation. In many cases, procedure has been regarded as a precondition for enacting distributive justice, as it advocates for equal participation when negotiating the distribution of costs and benefits as well as assigns responsibility of a given environment (Sikor, 2013). 3) Recognition: recognitional justice calls for understanding differences between identity, gender, culture, and customary rights (Martin et al. 2016, Betrisey et al. 2018). Much research suggests that recognitional justice can be a pre-condition for distributive and procedural justice, as it provides a safeguard to ensure that the aforementioned two dimension will be achievable (e.g., Schlosberg 2004, Martin et al. 2016, He et al. 2021). Moreover, these three dimensions of justice are not separate, but rather inextricably bound together, mutually supportive and cross-amplifying (e.g., Martin et al., 2014, He et al. 2021). While procedure can ensure distributive justice, distribution can adjust the power-balance to strengthen procedure (Ruano-Chamorro et al. 2021). Although recognition is a precondition, it can be enhanced by improved procedure and distribution (Sikor et al. 2014). It is the growing consensus among scholars that achieving these three dimensions of justice tends to produce positive environmental outcomes (e.g., Fisher et al. 2019, Dawson et al. 2017, He and Sikor 2015).

Separate from this, current analyses also recommend the perspectives of plurality and dynamism for understanding environmental justice (Zafra-Calvo et al. 2020, Betrisey et al. 2018, Brunnegger, 2019). Pluralism requires a broadened perspective to understand actors’ justice norms and how they differ across scales when local value systems come into conflict or overlap with global systems (Martin et al. 2014, Zafra-Calvo et al. 2020, He and Guo 2021). To address this, scholars have called for increased attention to local notions of justice (He and Sikor 2015). Justice dynamics are reflected in the spatial and temporal dimensions of justice (Brunnegger, 2019). This requires a holistic perspective to understand how notions and practices of justice can change over time and space. Contemporary study on environmental justice has also conceptualized understanding pluralism and dynamics of justice through a lens of everyday life and practice as a kind of “everyday” justice (Brunnegger, 2019). Both pluralism and dynamism of justice provide a broader perspective for justice analysis.

In the context of water governance, existing literature also attempts to address justice and farmer-managed irrigation systems through the normative framework. Remarkable work done by Boelens and his colleagues used cases from the Andes showing that local normative structure including, legal pluralism, water property rights, local identity, and value, which might guide local justice practices and notions in water governance (e.g., Mena-Vasconez et al. 2017, Boelens and Vos, 2014, Boelens, 2014). Further, Hoogesteger (2015) suggested understanding local normative structure in water collaboration and conflict resolution. As an institutional strategy, the local normative structure serves to enable local adaptation to water stress (Thapa and Scott, 2019), to struggle for water justice Zwarteveen and Boelens (2014), and to balance gender dynamics in governance (Meinzen-Dick et al. 2022). Thus, examining local normative structure entangled with the local notion of justice helps to understand collective action in water governance in a communal system, as local normative structure stands central in the definition of what is locally defined and perceived as justice. The notion of justice, therefore, is aligned with DPs (i.e., recognition, monitoring, decision-making, etc.) under the local normative structure (He et al. 2021, Zwarteveen and Boelens, 2014).

As such, we find integration of environmental justice and the normative framework to be a powerful tool for analysis of the commons. It allows us to broaden our understanding of the commons beyond simply that which results from institutional design or institutional bricolage. Rather, the commons can be seen as both outcome and process of peoples’ justice notions and practices. The environmental justice framework also provides us with a plural and dynamic perspective of justice notions and practices at multiple scales. Thus, in this research we examine differing notions and practices of environmental justice across a large-scale, multi-ethnic watershed using the three dimensions of justice notions and practices.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study site

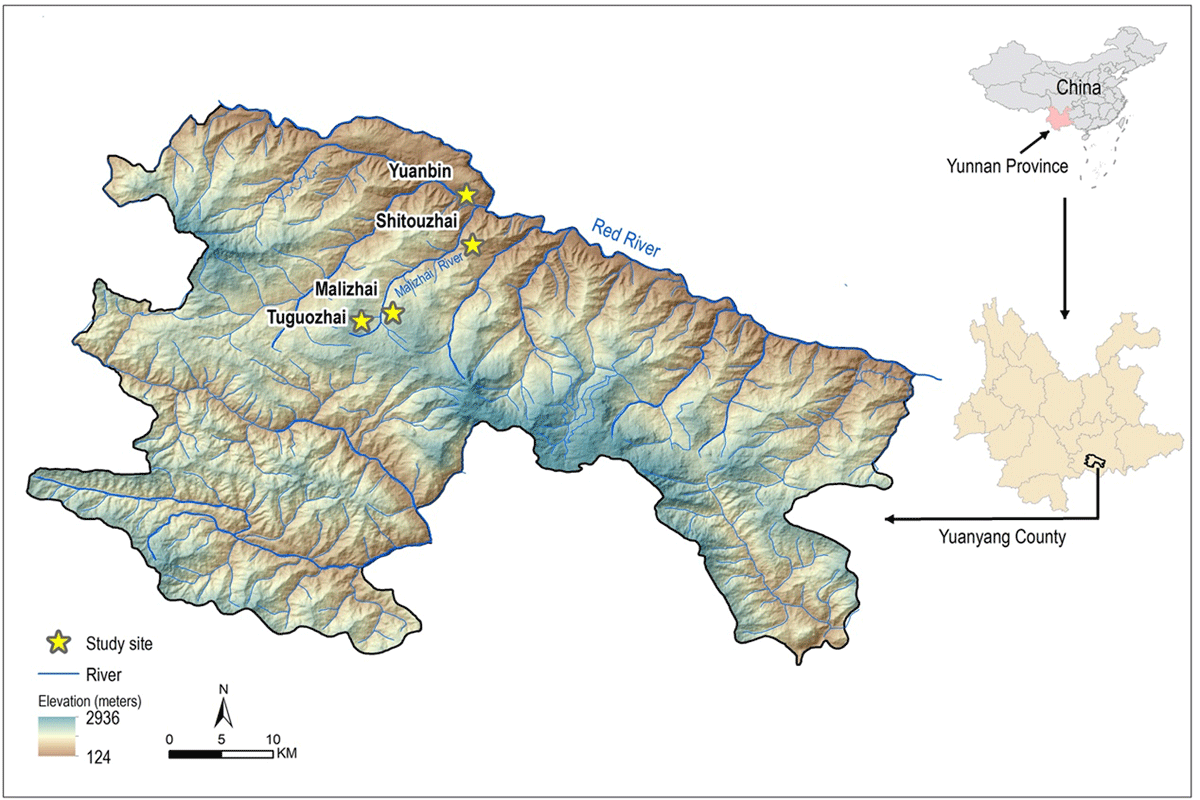

Fieldwork was carried out at the Malizhai watershed located in the core zone of the Cultural Landscape of Honghe Hani Rice Terraces listed by UNESCO World Cultural Heritage, Yuanyang County, Honghe Prefecture, Yunnan Province, Southwest China [Figure 1]. In total, nine administrative villages reside in the Malizhai watershed, consisting of the following seven ethnic groups: Hani, Yi, Dai, Zhuang, Yao, Miao and Han-Chinese. In total, 21,823 households reside in the watershed area with a residential population of 85,349. The total area of the Malizhai watershed covers 39,303 hectares with an elevation ranging from 600 to 2300 m.a.s.l., 60% of which consists of rice terraces on which approximately two-thirds of the total population depends for their livelihood.

Figure 1

Location of study sites.

Various ethnic groups are widely distributed throughout the watershed. Generally speaking, Hani and Yi have settled the upper levels, with Hani, Zhuang and Yao at the middle levels and Dai and Yi at the lower levels of the watershed. Given that rice terraces form a unique agroecosystem with local economic, ecological and cultural value (Jiao et al, 2012), water plays a pivotal role in the maintenance of this agroecosystem. Historically, the water has been collectively managed and shared by different ethnic groups in the watershed as a common-pool resource. Despite large differences in terms of ethnicity, culture, and agricultural practices, water is allocated and managed as a common property that meets the needs of different ethnic groups for irrigation and domestic consumption largely absent the rise of conflict and dispute. Successful allocation and management practices have enabled the continuation of the rice terraces as an important feature of local development, and it was eventually recognized and listed as a World Cultural Heritage Site by UNSECO (Gu et al. 2012).

The Malizhai watershed features heterogenous biophysical, socioeconomic and cultural components. This makes it an ideal site for examining justice notions of water management beyond Ostrom’s Eight Design Principles. Furthermore, given the ambiguity of water property rights in China (Wang et al. 2022), upstream and downstream dynamics of the Malizhai watershed provide useful insights for examining practical water management as on-site common property, which contributes to our understanding of how justice notions are embedded in and shared by local traditional institutions among an ethnically heterogenous body of Indigenous people.

3.2 Methods

This research uses an in-depth case study approach to obtain an empirical understanding of the allocation and governance of water resources in association with ethnic relations at the study site. An ethnographic approach was used for data collection, and intensive fieldwork was largely carried out over four periods: March to June 2016, July to August 2017, October to December 2018, and January to March 2019, as part of the first author’s PhD research. A follow-up visit was conducted by both authors in August 2021 to obtain insights into current local dynamics after the emergence of COVID-19. The fieldwork focused on four administrative villages at the Malizhai watershed: Tuguozhai Village with Hani and Yi people, Malizhai Village with Hani people, Shitouzhai Village with Yi people, and Yuanbin Village with Dai people. These four villages were selected to ensure equal representation of different ethnic groups located at different elevation ranges that share water from the same stream of the watershed. This village cluster helps us analyze upstream and downstream dynamics as well as the ethnic interplay between these communities in water management.

Primary data were generated via three empirical approaches. First, participant observation was widely applied as the bedrock of an ethnographic approach. Given that the first author has been working in this region since 2012, strong personal rapport and trust with both local people and government officials have already been established. This allowed the author to obtain observational data from participating in a wide range of local activities and events, including 1) local rituals and cultural ceremonies, 2) agricultural activities including seeding, transplanting, management, harvesting, and more, 3) water management activities such as cleaning and maintaining irrigation channels, and 4) political events such as village assembly to discuss water management, selection of channel managers, and more. Second, a total of 46 in-depth interviews were conducted with key informants composed of village heads, channel managers and maintainers, forest rangers, local township and county officials, women and elders. The semi-structured interviews allowed the authors to learn about both historic and current practices surrounding water management as well as peoples’ perspectives of justice in water management. Third, a total of 10 focus group discussions were carried out with villagers, officials, elders and women groups. The focus group discussions are particularly useful to probe and record collective perspectives of justice in water management and allocation. Based on these, robust ethnographic data were gathered and integrated to generate a clear picture of local dynamics of justice in water management and allocation between different ethnic communities in the watershed. The in-depth case study approach also allows us to understand the ways in which local agricultural water management practices affect the development of waterscapes under a combination of socioeconomic, political, cultural, and biophysical contexts.

4. Practice of justice in irrigation water at Yuanyang Hani terrace

4.1 Distributive justice

Water allocation in the Malizhai watershed follows a practice of distributive justice (Figure 2). Streams and springs are derived from the forest at the top of the mountain, and natural run-off is the main source of water for rice production in the terraces. There are simple wood or stone dams set up along the streams and rivers for water allocation. Along the watershed, thousands of wood or stone dams have been established for water allocation in the main-stream, sub-stream or small channels. Villagers have cut and carved passageways into wood and stone dams. The cuts and carvings direct the water flow to different smaller channels that lead to a particular rice field or allow the water to continue to flow to a lower level. A large dam with a wide passageway is generally set up on the main-stream, while smaller dams with narrow passageways are set up on small channels and sub-streams. These passageways can be traced all the way to the water source at the top of the watershed forest.

Figure 2

A: Massive terrace paddies require significant water use; B: channel maintained by local people for irrigation; cut passageways on wooden dam C and carved passageways on stone dam D.

Practically, the wideness of the cutting or carving determines the quantity of water allocated, which varies to ensure sufficient water to a particular rice paddy or water users at lower levels. For calculating water flow quantity, a local unit for water allocation was set up named “one cut” (yi ke, 一刻). One cut is typically as wide as four fingers of an adult male, excluding the thumb, which is sufficient to irrigate a field capable of producing 400 kg rice annually. As such, a width of two fingers is a “half cut” (ban ke, 半刻) and one finger is a “one-quarter” cut. Determining the width of cuts at the wood or stone dam for water allocation is based on the rice production of a given paddy. As the elevation changes across the montane topography, rice paddy productivity also varies. Thus, water allocation is not based on the area of land, but rather on the production of rice, which is aimed to promote equality of agricultural return regardless of unavoidable natural factors such as elevation, temperature and soil health. If several people must share one cut of water, there is a general rule: the upper paddy must fill first before the lower paddy can fill. In this case, the upper-level water users have to direct the water to the lower-level field after their water demands are met. Otherwise, they are subject to fine. A gender division in water allocation is that women have full access to water use for irrigation and men take responsibility for maintaining the channel to ensure access to the water.

Water allocation practices also secure equity across different ethnic groups in different villages. The rice paddies of the Malizhai watershed are distributed in a mosaic pattern among different village and ethnic groups. In many cases, adjacent land is managed by households from different villages, despite close proximity, requiring them to share water sources for irrigation. Luckily, there is widespread regional acceptance of cutting and carving on wood and stone to determine water flow. Villagers are in agreement regarding the rules governing water allocation based on land productivity benchmarks. The widespread adoption of these rules across different groups and villages has facilitated the long-term historical practice in this region. As stated by a Hani villager:

“Rules of water allocation are inherited from our ancestors. If you break the rule, steal water, or engage in unapproved water allocation, you will be punished regardless of ethnicity and village [origins]……….these traditional rules for water distribution are locally legitimated, authorized and enforced, followed by everybody. [2017-7-18 in Tuguozhai Administrative Village]

There are also considerations of temporal justice in water allocation. For paddy rice cultivation, the Yi and Hani people in Shitouzhai Village, located at the lower level, begin transplanting seedlings in March and April, after they finish maintenance and repairs on the ridges separating terrace plots. At this time, people at the upper levels of the watershed do not block the wooden dam to ensure sufficient water flow to lower levels. When farmers at upper levels begin transplanting later in April and early May, villagers at lower levels conversely agree to allocate more water for the upper villagers. This temporal consideration fits well to the biophysical pattern of rice growth at different elevations while sidestepping conflicts and ensuring equitable distribution.

In sum, distributive justice in the Malizhai watershed is associated with spatial, temporal and social dimensions to deliver equal allocations of water across different lands, seasons and ethnic groups/villages. Despite biophysical variance, such as elevation, temperature, and soil fertility, considering spatial and temporal dimensions in water allocation has ensured long-term equitable access to water by all the region’s diverse inhabitants. Given that these are time-honored practices, indigenous peoples assign a great deal of authoritative weight to water distribution rules, which are followed even by members of different ethnic groups.

4.2 Procedural justice

Procedural justice is also practiced in the Malizhai watershed for the management of water allocation for terrace paddies. Traditionally, local channel managers (gou zhang 沟长) and maintainers (gan gou ren 赶沟人) are selected for the management and maintenance of the channels, wood/stone dams and water allocation. An annual assembly is held for villagers that draw upon the same water source in the Malizhai watershed. During the assembly, villagers will elect both channel managers and channel maintainers. The manager is a particularly important role in whom the powers to make decision-making about water allocation practices as well as when to release dam water are vested. Traditionally, certain criteria must be met for a manager to be deemed eligible for selection: 1) the manager must be an adult male come with strong local kinship ties; 2) his house must be allocated water in the irrigation area; and 3) his kin are earlier residents of this area who originally located the water sources and established the terrace systems (an appeal to strong traditional authority). As such, the manger role does not change often, typically only when somebody becomes old enough to step down. Also, as managing and maintaining require numerous labors force and coordination, there is a tradition that women are rarely involved in those roles.

Apart from the coordination of water allocation at the intra-community level, the manager also takes responsibility to coordinate water allocation at the inter-community level. In this case, the manager may come from any ethnic group who shares a given source of water. For channel maintainers, they are voted on and must be male, responsible, fair and have a strong sense of civic duty. The maintainers take responsibility for cleaning channels and dams, checking the cuttings, as well as daily maintenance. Both managers and maintainers control water flow and irrigation across different villages and ethnic groups. As one Yi villager stated:

“Our Shitouzhai Village [Yi people village] shares the same water source with the Hani people from the Malizhai watershed upstream and Zhuang people downstream. We use wood and stone cutting for water allocation……whatever Hani, Yi or other ethnic group…… we gather for a water allocation meeting, which is normally held in March or April according to the lunar calendar. At that time, we decided up on the amount and timing of water allocation. Also, manager and maintainer will be selected at this time.” [2016-10-27 in Shitouzhai Village]

Both channel managers and maintainers are paid by water users for their efforts in water allocation and channel management. Historically, they were paid with rice harvested in the irrigated area they managed. A sum of 75 kg for every one cut of water was paid by each water users. Nowadays, 3000 RMB (about 450 USD) per cut is paid. In return, channel managers and maintainers must not only oversee water allocation affairs but also mediate disputes if they arise.

Currently, along with economic development and rural restructuring, the channel manager also adopts the role of village head who has been elected by villagers to act in the capacity as both traditional water manager and official political role as head of the village committee. This integration of traditional authority with official administration legitimizes local practice via the appearance of government support, as the village head is also selected via village election procedure. The channel maintainer is now appointed by the village committee. Those who undertake this role tend to be relatively poor or own little land. As such, villages believe the role could help reroute income to those who have been left behind in the surge of economic development. This arrangement is widely practiced among different villages and is perceived as fair treatment. As one Hani villager stated:

“Now we do not elect the channel maintainer…. We assign the position to those poor and landless….they can benefit from channel maintenance, as the work receives remunerations. Villagers do not complain about this arrangement. They [villagers] think it is fair, as channel maintainers are poor.” [2021-08-07 in Malizhai Village]

Apart from channel managers and maintainers, there are forest rangers who play a crucial role in this terrace waterscape. As the water is sourced from the top of the mountain in the watershed, good forest coverage is vital for providing sufficient water. In the Malizhai watershed, the watershed forest is located in an area traditionally belonging to three villages shared by the Hani, Yi, Dai and Zhuang people. The forest was subdivided into 37 smaller districts, with 37 forest rangers selected for management. The role of forest ranger also requires meeting several criteria, as stated by one villager:

“Rangers are crucial for our Hani terraces, as protecting the forest is our way to protect the mountain, and protecting the mountain is our way to protect water…….this lets us have water to irrigate our terrace paddies and maintain our livelihoods. Forest rangers must 1) be well-respected in the community; 2) exhibit fairness in personality; and 3) have a long kinship heritage. Given that the forest ranger role is a kind of rule enforcer, we respect kin inheritance and value this personality of fairness for following and enforcing rules and responsibilities.” (2017-4-6 Malizhai Village)

Forest rangers take responsibility for protecting forestland; they adhere to and enforce the rules collectively agreed upon by local communities. While there are variations in the minutiae of some rules, general principles are largely similar across these three villages. For example, in Malizhai Village, people who fell one individual tree without approval will be punished and required to plant 10 young trees. Grazing in the forest will be punished by being required to participate in forest fire control and restoration. Given that these rules represent the distillations of collective and local moral judgments, they are overwhelmingly followed by villagers. In this, they have codified a legal code highly congruent with lifestyle practices, reinforcing broad societal buy-in. In the past, forest rangers were paid by water users in grain, but nowadays government subsidies cover their salaries. The government not only provides financial support but also lends legal and administrative resources for forest protection.

When there are extreme weather, i.e. drought and flood, special action will be taken. During the drought times, people have set up a rule for limited water use based on the area of productivity for allocation to avoid competition. When there is a flood, channels will function for flood discharge, and then the managers and maintainers will take a special role in the management of the channels to ensure that people can cope with the extreme weather. There might be a conflict in water use during the extreme drought. As such, all people had to come together for discussing the strategy including, seeking new water sources in the forests, restricting water use, and improving water harvest from streams etc. All those activities have been done in a way of collective action.

To sum up, procedural justice practices in the Malizhai watershed are undergoing a process in which traditional arrangements are integrated with modern government administration along with institutional development. This transition has progressed smoothly, as the integrated arrangement is built upon traditions that have been agreed upon and practiced by local villagers for many years. The combination of a public election process that emphasizes traditional criteria in selecting channel managers, maintainers and forest rangers has legitimized the management style of the watershed. Moreover, infusing poverty alleviation objectives into the role of channel maintainer has been widely accepted and viewed as a fair strategy for supporting the rural poor. Government efforts have marshalled both financial and institutional support to buttress traditional institutions and practices.

4.3 Recognitional justice

The practice of managing the waters as a commons manifests through notions of recognitional justice at the 1) inter-community and 2) external level. This recognition ensures that cultural differences, ethnic diversity, and indigenous practices will continue to be recognized and supported, despite the significant heterogeneity found at the Malizhai watershed.

1) Inter-community recognition

At the inter-community level, recognitional justice is practiced in different ways to support collective action on water use and rice cultivation. For example, the variation in elevation allows for the possibility of people from different villages to cultivate rice at different times. This temporal difference also allows for labor exchange among different ethnic groups in different villages during planting and harvest seasons. Those seasons are labor intensive due to the unsuitability of using heavy machinery on terraced mountainsides. Hani, Yi, Dai and Zhuang people from different villages typically organize between different households for labor exchange. It is typical that Yi and Hani from higher elevations typically come down to help Dai and Hani in the lower watershed during the early planting and harvest season, while the Yi and Hani receive support afterward. Apart from labor exchange, it is also common practice to share water buffalos between different ethnic groups from different villages. This is due to changing vegetation available at different altitudes across different seasons, providing a year-long source of fodder for the buffalo. Buffalo play a critical role in undertaking land preparation for households at all elevation levels. Thus, while cultivation practices may vary, different ethnic groups across different communities mutually recognize the essential need for labor exchange and communal water buffalo sharing to maximize rice production in the Malizhai watershed.

Inter-community recognitional justice also manifests via local cultural ceremonies and ritual practices. At the lower level of the watershed, the Dai people from Yuanbin Village share a small stream with the Yi people of Shitouzhai Village. Each year, a water ritual ceremony is held at the water source, where there is cave. The Dai imbue this cave with sanctity as a holy site that provides irrigation waters crucial to their livelihoods. However, the cave is located in a watershed forest district protected by the Yi people. On a Dragon day selected in March of the lunar calendar, the Dai will invite the Yi to come together to hold the ritual ceremony at the cave. The Dai will contribute pig, meat, and alcohol as well as other materials and food for the ritual, while the Yi only need to attend. Although this ritual practice is a typical Dai practice based on their religion, the Yi people recognize it as an important component of forest management. The participation of the Yi people reflects a solemn respect for Dai cultural beliefs around water. This reciprocated recognition has strengthened mutual understanding of their divergent cultural practices, which ultimately contributes to good water management. As most interviewed Yi villagers at Shitouzhai Village stated, they have never had a conflict nor dispute with Dai people in water allocation, as they respect each other.

An important sacred mountain can be found in the upper watershed named East Guanyinshan, which is also a key water source of the Malizhai River. East Guangyinshan Mountain is in the official territory of the Hani (Aichun village). As a sacred mountain, it is the locus where the Hani conduct a traditional ritual2 ceremony called Bomatu (波玛突). The ritual ceremony is held on Horse Day in March of the lunar calendar and attended by all communities in the Malizhai watershed, including the Yi, Zhuang, Hani, and Dai people—indigenous peoples who benefit from East Guanyinshan as the ultimate large-scale water source in the region. During the ritual ceremony, the Hani people lead the procedure, which is followed by the Yi, Zhuang and other ethnic groups. It is important to hold this ceremony before the rainy season, as the rituals offer respect to Hani deities for safeguarding inhabitants of the watershed and beseech them to provide sufficient water in the coming rainy reason. In the ceremony, all in attendance will make contributions of pig, meat, cattle, and more. All ethnic groups in the watershed revere the sacred mountain, despite divergences in religious systems. The collective ritual ceremony organized by different ethnic groups suggests to many Hani practitioners that the mountain is recognized as sacred by all communities in the watershed. As a Hani villager stated

“Although the deity residing in East Guanyinshan is ours [Hani], the Dai, Yi, Zhuang and Hani who also use the water for irrigation will come to the ritual ceremony to pay respect to our Hani God. Our God is fairest and will protect us as well as them [other ethnic groups]. Our ritual worship in ritual will please the God, who will then provide sufficient water to us [Hani] at higher elevations; then, the people at lower elevations will also have enough water. [2016-4-13 in Malizhai village]

2) External recognition

The practice of water management by different ethnic groups is also widely recognized and respected by external actors at local, national and international levels. At the local level, the local institution for determining water allocation as well as the selection of channel managers and maintainers are all recognized and respected by local government entities. This recognition has enabled water governance practices to continue in the same traditional vein of the past. Moreover, integration with modern administration systems and traditional management practices have empowered and legitimated ancestral practices. As such, local rules for water allocation as well as local practices for selecting managers and maintainers can continue unabated and further integrate with modern state institutions and administrations. At the same time, government entities are financially supporting channel maintainers and managers to cover their salary. Apart from providing salaries, local rituals have also received recognition and support from the government. As for the collective ritual ceremony in Guanyinshan, each year the government officially provides 1500 RMB (about 250 USD). Their explicit monetary support is an official recognition of local water management practices.

Traditional water allocation practices are also recognized at the provincial and national levels. A wide range of people have been listed as inheritors of intangible cultural heritage, including those who conduct the ritual ceremony at East Guanyinshan, those who facilitate community-level ritual ceremonies, those who specialize in water and terrace management, as well as those who are specialists in local rice cultivation. Currently, there are seven people in the Malizhai watershed listed as provincial and national inheritors of intangible cultural heritage. Government funding has aided the transmission of their traditional knowledge to the younger generation, facilitating the continuation of traditional practices into the future. Thus, the listing not only provides an official recognition of the critical role local cultures and practices play in water management, but also strengthens local traditions intergenerationally.

At the international level, the terraces as well as local practices for water management have also been recognized. In 2013, the Malizhai watershed, as a core area of the Honghe Hani Terrace, was included as a World Heritage Site for conservation by UNESCO. UNESCO recognized the terrace ecosystem as a combination of four elements that co-create this unique social-ecological system composed of people-terrace-water-forest. Per UNESCO documentation, the co-creation of these four elements reflects both a combination and interplay of natural and cultural practices in the Honghe Hani Terrace. Numerous ethnic groups play important roles in producing this waterscape that is embedded within local agricultural systems, water management practices as well as forests. Those four elements thereby coalesce into a social-ecological nexus with serious implications for ethnic harmony. After recognition by UNESCO, there was an upswell in investment for conserving the terrace agricultural system via protecting local cultural and water management practices. Apart from UNESCO, the Honghe Hani Terrace was certificated as a National Wetland Park in 2007, Global Important Agricultural Heritage in 2010, and seventh batch of China’s Key Cultural Relics for Protection in 2013.

In sum, recognitional justice in the Honghe Hani Terraces manifests at both inter-community and external levels. While different ethnic groups do in fact co-exist, inter-community recognition of cultural differences among them provides a crucial foundation for collective action in water management. This recognition also ensures that rulemaking, facilitation and communication all contribute to well-managed water. Externally, recognition from government and international organizations has provided significant support to local practices and cultural activities in water management. There is not only financial support, but more importantly administrative and institutional support from the government and international organizations, legitimizing and enhancing the effects of management. Thus, recognition at both inter-community and external levels functions to safeguard local collective traditions in agricultural water management.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The in-depth case studies of irrigation water governance in Southwest China featured herein have significant theoretical and empirical implications. When enriched with an environmental justice framework for analyzing the commons that builds upon the foundation of Ostrom’s Eight Design Principles, three noteworthy points emerge.

First, the research reveals institutions that governing water commons are not ideally designed, as also suggested by other scholars (Araral et al. 2019, Cleaver, 2012; Cleaver and De Koning, 2015, Wang et al., 2019). Conversely, here, the institutions that govern irrigation waters are developed, practiced, and adopted based on notions of justice shared by local people, a multi-stakeholder collectivist phenomenon that has also been observed elsewhere in other types of natural resource management schemes (e.g., He et al. 2021). In this case, notions of justice lie at the core of water use, allocation, and distribution, guiding all actions. As shown in the Malizhai watershed, there is significant overlap between different ethnic groups’ justice practices in water management, i.e. 1) distributive justice in equitable water allocation considering temporal and spatial dimensions, 2) procedural justice in the traditional selection of managers was incorporated within formal administrative structures, and 3) recognitional justice in cultural differences externally and internally in the communities. As those notions of justice are held by stakeholders, they have built a foundation for collective action around water governance as a commons. Therefore, it should be increasingly acknowledged that justice plays a preconditional role in the successful management of natural resources, particularly for common-pool resources (e.g., Martin et al., 2014, Fisher et al., 2018, Schlosberg & Collins, 2014, Schroeder & McDermott, 2014, Zeitoun et al., 2014, He et al. 2021).

Second, the research also suggests that environmental justice should originate from a plural and dynamic perspective, which has also been found elsewhere (e.g., Zafra-Calvo et al. 2020, Betrisey et al. 2018, Brunnegger, 2019). Pluralistic notions of justice are particularly reflected within the local value system, which could substantially differ from common notions of justice (Martin et al. 2014). As shown in the Malizhai watershed, notions of justice were largely shaped by local value systems, which differ from global and common justice notions, i.e., 1) distribution of water considering the plantation periods and land productivity over land area, which diverge from other common notions of equality or egalitarianism. 2) selection of managers to combine traditional practice and formal administration in favor of disadvantaged people, which is different from Western notions of procedural justice such as public participation, voting election systems and downwards accountability, and 3) involvement of different ritual and religion practices among different ethnic groups reflects the mutual respect and recognition of the existence of potentially radically different cosmologies conceived of by different ethnic groups. Thus, pluralistic and dynamic environmental justice requires a contextualized understanding of indigenous knowledge, cosmologies and practices, as also suggested by other scholars (Zafra-Calvo et al. 2020, Martin et al. 2016).

Third, this research supports that examining local notion and practice of justice from normative framework perspective helps to reveal the intersection between justice and the DPs. (e.g. Mena-Vasconez et al. 2017, Boelens and Vos, 2014, Boelens, 2014), the local normative structure stands central in the definition of what is locally defined and perceived as justice, which is interlinked with the DPs. In the case of the Malizhai watershed, 1) local normative structure defined customary water rights (i.e. clearly boundary in DPs) in alignment with the local notion of distributive justice in both temporal and spatial dimension, 2) local normative structure in selecting channel managers and maintainers is in alignment with the decision-making, monitoring, and decentralization of DPs, which is practiced as procedural justice in water governance, and 3) local value and identity in the local normative structure were recognized widely among the different ethnic groups, local government authorities, and international organizations, which is in alignment with recognition in DPs and recognitional justice in the justice framework. Thus, the understandings of the local normative structure provide a perspective to examine how local justice was practiced and perceived from a plural and dynamic dimension, which enrich the relatively static DPs perspective in governing commons (Mena-Vasconez et al. 2017, He et al. 2021).

Finally, policy recommendations drawn from this empirical research comprise three parts. First, there is a renewed call for a wider understanding of the role of justice in resource management, particularly for common-pool resources. When numerous heterogenous populations must collaborate for sustainable natural resource management, justice is a precondition for effective collective action. Thus, government actors should invest in advancing local justice practices to strengthen common-pool resource management strategies. Second, a multidimensional type of justice must be considered over a unidimensional one. Distributive, procedural and recognitional justice are complexly imbricated, supporting one another while layering and expanding the overall scope of justice. Thus, local justice practices should holistically consider the potential ripple effects across these three notions. Third, pluralistic and dynamic justice in local value systems cannot be neglected when seeking to bolster institutions that enact local justice. For example, local notions of justice can be pluralistic, changing over time and differing from popular notions of justice. Thus, a deep understanding of local value systems, including local traditions, cultures, cosmologies, indigenous knowledge and more, is required to refine justice actions and amplify investments.

Notes

[1] According to Ostrom (1990), the Eight Design Principles include: 1) clearly defined boundaries, 2) rules governing use of common goods fit to local needs and condition, 3) a system for decision-making that allows individuals affected by the regulations are include in the groups that can modify those the regulations, 4) monitors drawn from, or accountable to the community who actively audit the rule be followed, 5) graduated sanctions for members who violate regulations, 6) conflict-resolution mechanisms that are low cost and easily accessible for members of community, 7) recognition of local rights to devise their institutions by external authorities, 8) decentralized decision-making in multiple layers of nested enterprises.

Acknowledgement

The early version of this manuscript was benefited from constructive comments from two anonymous reviewers and the editor-in-chief. English editing from Austin G. Smith and mapping by Huafang Chen is also acknowledged.

Funding Information

The research was financed by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 72063037) and the National Social Science Foundation of China (Project No. 19CMZ048), and the Ministry of Education of China (Project No. 16JJD850015).

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.