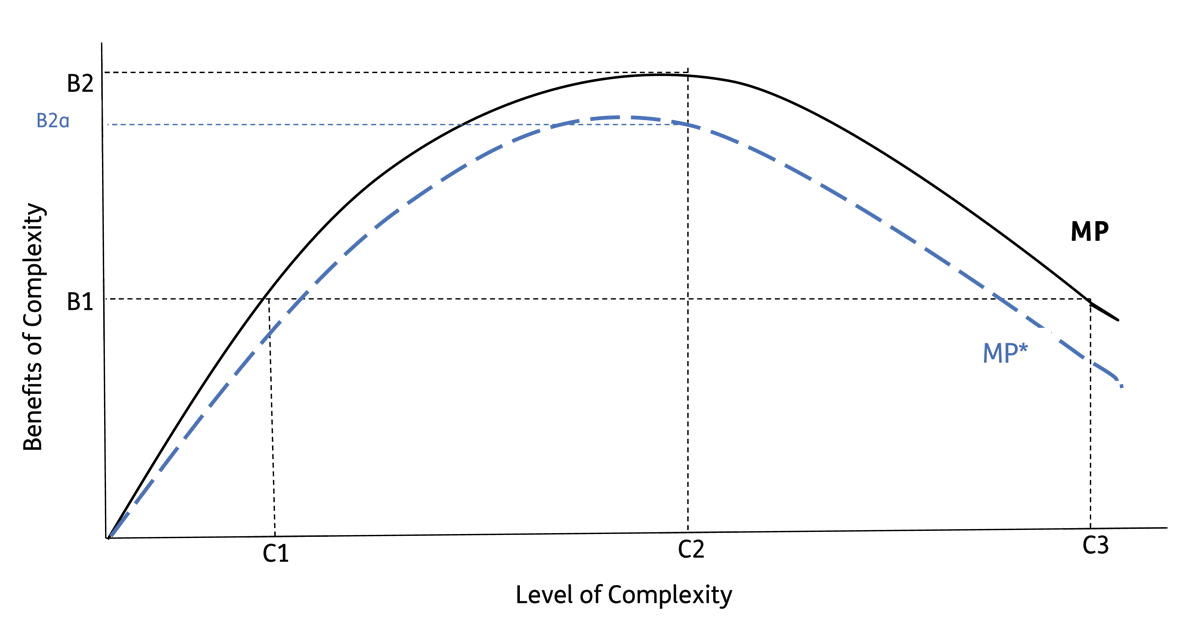

Figure 1

The marginal product of increasing complexity.

Source: Adapted from Tainter (1988: p119).

Table 1

Steppe Game.

| PLAYER 1: STATE | PLAYER 2: SOCIETY | |

|---|---|---|

| STRONG | WEAK | |

| strong | (0; 0) | (3; 1) |

| weak | (1; 3) | (0; 0) |

[i] Source: Adapted from the battle of the sexes payoff matrix.

Table 2

Reduced normal form.

| STATE | SOCIETY | |

|---|---|---|

| STRONG | WEAK | |

| Doesn’t & strong | (0; 0) | (3; 1) |

| Doesn’t & weak | (1; 3) | (0; 0) |

| invest & strong | (-i; 0) | (3-i; 1) |

| invest & weak | (1-i; 3) | (-i; 0) |

[i] Source: Adapted from Van Damme (1989).

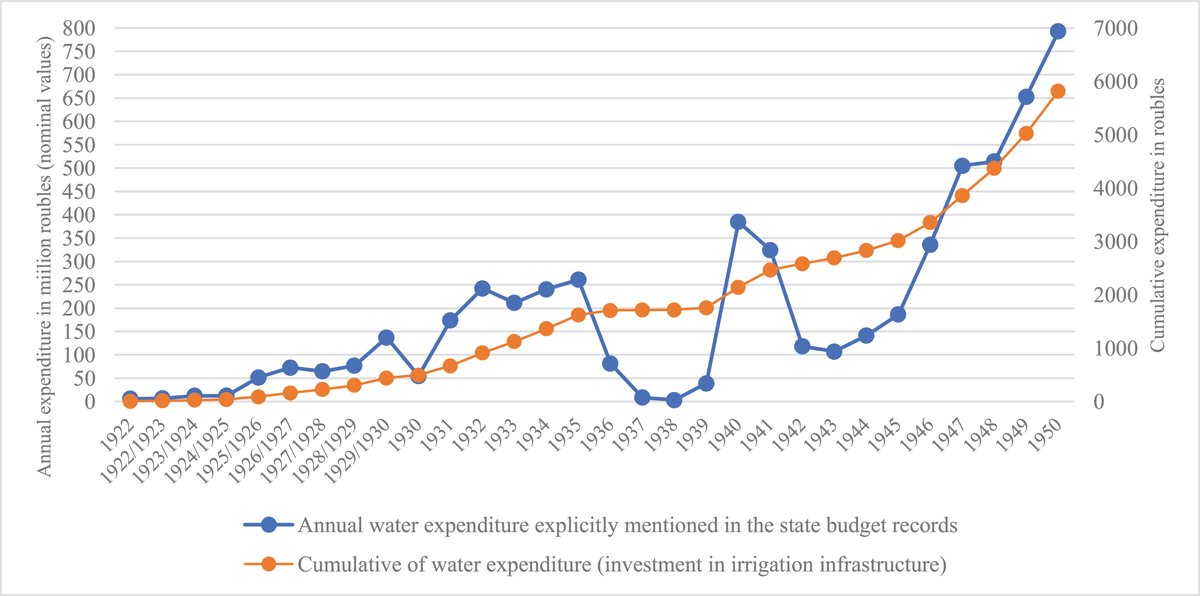

Figure 2

Soviet central state investments in irrigation infrastructure until 1950, expenditures are in nominal rouble values.

Source: Istmat.info (2020).

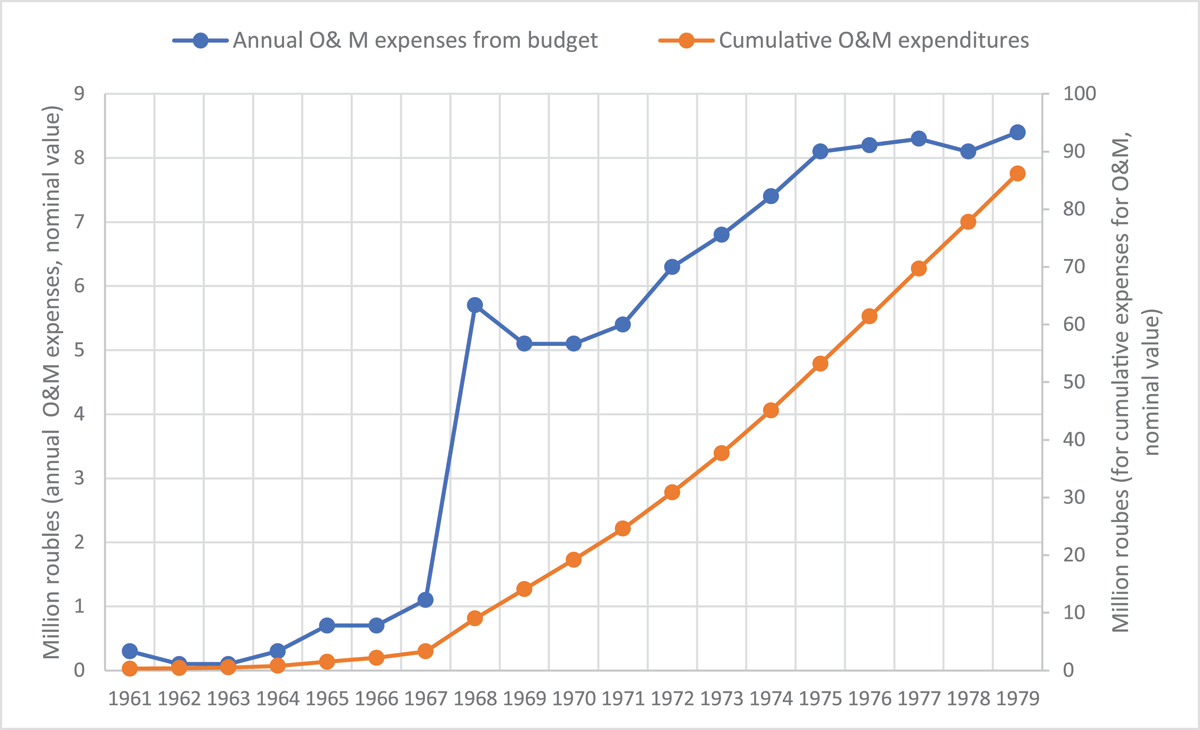

Figure 3

O&M expenses from budget: Water sector, Hungry Steppe, in nominal million roubles.

Source: Dukhovny & de Schutter (2011).

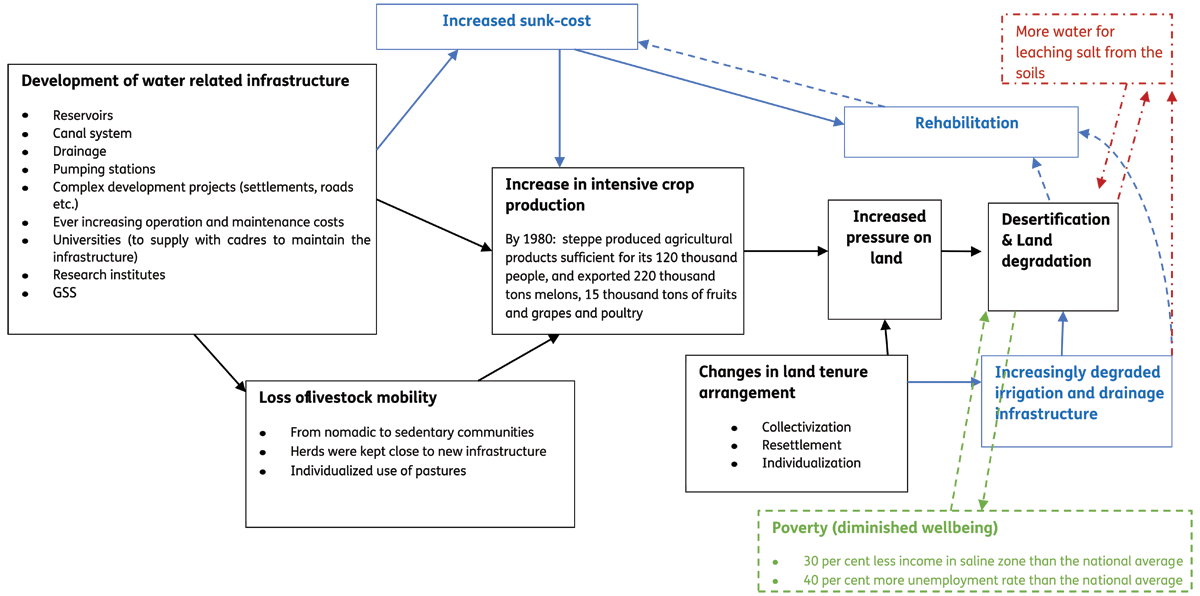

Figure 4

Recurrent societal drivers of desertification case in Hungry steppe. Positive feedback loop sourced from sunk cost effect.

Source: Adapted from D’Odorico et al. (2013) to illustrate land degradation drivers using sources for Hungry Steppe as Obertreis (2017); Bucknall et al. (2003); Abdullaev et al. (2007); Alimaev & Behnke (2008), positive feedback literature as Arthur (1994), Kay (2005) and Heinmiller (2009), land degradation and poverty interlinkage literature Barbier & Hochard (2018) and Abdullaev (2004).

Table 3

Possible values of and associated stable solutions. Positioning of the Hungry Steppe project across set of stable solutions. Scenario A.

| PROJECT PHASE | CONDITIONAL VALUE OF | THE STABLE SOLUTION(S) | THEORETICAL JUSTIFICATIONa | REFLECTION IN REALITYb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsarist Russia | 0 < i < 0.25 | {Doesn’t & strong; weak} | State gets maximum payoff; Society cannot signal a deviation | |

| {Invest & weak; strong}: | State wins from investing hence invests. It behaves weakly because deviation by State cannot be an unambiguous meaning. |

| ||

| Early Soviet years | 0.25 < i < 2 | {Doesn’t & strong; weak} | Only one outcome survives the iterative elimination of dominated strategies. The State does not invest, but it gets its most preferred equilibrium. The availability of an additional subgame, even if not used, has significant consequences. |

|

| Post 1950s | 2 < i < 2.25 | {Invest & strong; weak} | After State invests, Society responds by being weak, as the other alternative is dominated strategy and hence eliminated (not chosen). Intuitively stable. By investing (choosing a particular subgame), the State signals the Society own intentions, and the Society has no other option but to choose to be weak |

|

| {Doesn’t & strong; weak} | Because Society never knows whether the State will continue as strong or weak if it does not invest. Singletons. |

| ||

| {Doesn’t & weak; strong} | ||||

| 1990s–present | i > 2.25 | {Doesn’t & strong; weak} | Both strategies coupled to investment is dominated by the maxmin strategy so that additional option is entirely irrelevant, and the game reduces to the one in Table 1 (Steppe Game, i.e., Battle of Sexes) |

|

| {Doesn’t & weak; strong} |