Introduction

In 2016, M. Laborda-Pemán and T. De Moor issued a call to advance the conversation between commons scholars and historians (Laborda Pemán & De Moor 2016). As they argued, historians could benefit from an understanding of the different theoretical frameworks developed in the commons literature, while contributing conceptual tools and empirical knowledge to improve the assessment of institutional change. Works on historical commons have indeed demonstrated the applicability of theoretical proposals elaborated by common scholars, while also showing how historical studies can enlighten the factors conditioning the emergence, reproduction, transformation, and eventual disappearance of commons over time, thus furthering our understanding of past and current societies more broadly.

In Europe, the period between the fifth and the eleventh centuries, which for convenience I will here refer to as the early medieval period, has remained largely unexplored in the light of these recent debates – there are significant exceptions, though, most notably for the British Isles, building on a wealth of previous work on historical commons in the region (Oosthuizen 2007, 2013a, 2013b, 2016). There is a widely held assumption that before the twelfth or thirteenth centuries the institutions for the collective management of natural resources were less widespread and formalised than they would later become. Certainly, commons from the early medieval period are less visible in the historical record – both written and material – and the evidence available resists easy comparison with the more forthcoming sources that underpin studies on later historical commons, particularly those richer in normative information (De Moor et al. 2016; Farjam et al. 2020). Why, then, should we venture into such an unpromising land?

On the one hand, as S. Reynolds noted (1984), the institutions for collective action that abound in the twelfth- and thirteenth-century sources had their roots in earlier times. Commons may also have had a significant weight in the organisation of local territories before that (Wickham 1995: 15–16), while in many regions collective institutions were central for governance both at the local and the supra-local scales (Barnwell & Mostert 2003; Pantos & Semple 2004; Semple & Sanmark 2013). The development of commons throughougt the medieval period thus needs to be assessed against broader historical processes beyond the political ‘conditions’ and ‘motors’ (De Moor 2008) and the local determinants (Curtis 2013) of high medieval societies.

On the other hand, the peculiarities of early medieval societies provide us with an opportunity to explore commons and their transformation over time in socio-institutional settings that were markedly different from those of later times (cf. Ostrom 1990: 101–102). In comparison to earlier and later periods, in Western Europe this was a time of relatively low social complexity.1 Lords and political authorities had a limited capacity to interfere on the ground, and in some regions local communities must have enjoyed a significant degree of autonomy. The balance could change over time as polities developed or collapsed, and in these processes local institutional arrangements retained a significant weight (Escalona et al. 2019; Martín Viso 2016). We can thus analyse how processes of polity building and collapse at low levels of social complexity may have impacted upon commons, and also how commons conditioned and fed into such processes.

Importantly, early medieval Western Europe was highly fragmented, and there was great variation in local and regional socio-economic and political conditions (Wickham 2005; Zeller et al. 2020). Consequently, the relevance of commons – where they had any – must have differed significantly. While a generalised model for the appearance and management of commons cannot be attempted at this stage, there are solid grounds to argue for a comparative approach. For most regions, the processes triggered by the collapse of the Roman Empire provide a shared background and mark a difference with the areas beyond the borders of the Empire (e.g.: Lindholm et al. 2013) that can be also worth exploring. The centrality of commons in the structuration of local and supra-local territories in the post-Roman centuries is increasingly recognised (Martín Viso 2020c), and so is their significance in the development of political authority and of aristocratic and ecclesiastical estates, as well as in the increasing formalisation of local communities towards the later part of the period (e.g.: Devroey & Schroeder 2012; Martín Viso 2020a; Mouthon 2014; Rao & Santos Salazar 2019).

This paper will focus on one particular region, NW Iberia, in order to explore these issues. Research on commons has long been popular among historians working on late medieval and modern Spain (Beltrán Tapia 2018), but has remained largely marginal to the historiography on the early Middle Ages until very recently (cf. García de Cortázar & Martínez Sopena 2007; Fernández Mier 2018). Only in the last years have a number of research projects informed by current developments in commons scholarship begun to develop, combining written source analysis with archaeological and ethno-archaeological approaches.2 This paper will first consider the historical context against which the first documented commons should be assessed, and then concentrate on the written sources from the ninth to the eleventh centuries in order to identify how commons scholarship may contribute to the analysis of early medieval commons – with particular attention to critical institutionalism (Cleaver 2012; Cleaver & de Koning 2015; Hall et al. 2014) –, and to probe some of the avenues that might facilitate dialogue with commons scholars and historians working on later periods. Ultimately, the aim is to present some lines of enquiry that could further empirical work on the region, foster comparative analysis with other European regions, and ground empirical and theoretical contributions to commons scholarship based on early medieval evidence.

Early Medieval NW Iberia in Context

Over the las three decades, our knowledge of the early Middle Ages has radically changed. The collapse of the Roman Empire was once seen as a shock that threw agrarian economies in Western Europe into a period of backwardness. Western European societies would only overcome this after centuries of slow but sustained economic growth, which historians regarded as a precondition for the crystallization of the feudal forms of social and political organisation that were deemed characteristic of the high Middle Ages (Duby 1973; Fossier 1982; Marquette 1990; Poly & Bournazel 1980). While the demise of socioeconomic and political complexity in the post-Roman centuries is unquestionable, more recent accounts highlight the various ways in which societies adapted to it (Horden & Purcell 2000), and have identified the ‘long eighth century’ as a turning point marked by the intensification of agricultural production and husbandry regimes (Banham & Faith 2014; Henning 2009; McCormick et al. 2014; McKerracher 2018; Quirós Castillo 2011); changes in the configuration of settlement patterns and agrarian landscapes (Hamerow 2002; Peytremann 2003; Quirós Castillo 2009; Rippon 2008; Yante & Bultot-Verleysen 2010), and further economic integration at a regional and inter-regional level (McCormick 2001), all of which is associated to the consolidation of an elite strata increasingly differentiated from the rest of society (Bougard et al. 2006; Loveluck 2013) and the development of more complex polities (Bassett 1989; Costambeys et al. 2011; Gasparri 2012).

In NW Iberia, the collapse of the Roman Empire in the late fifth century, and subsequently that of the Visigothic kingdom following the Arab conquest of the early eighth century, led to a major transformation of settlement patterns and economic networks. By the mid eighth century the area lay beyond the control of the Muslim rulers established in the south. A number of small-scale polities emerged in the north, but their territorial sway remained limited until the mid-ninth century (Castellanos & Martín Viso 2005; Fernández Mier 2011). The situation varied regionally. In areas like the Duero meseta, settlement patterns changed as former urban territories fragmented and Roman villae waned (Escalona 2006b). Isolated farms, hamlets and small concentrated villages began to emerge, displaying evidence for more localised forms of farming and the consumption and distribution of produce (Tejerizo-García 2015; Vigil-Escalera Guirado 2007). In the Central Mountain Range, upland forests recovered in the post-Roman centuries, but by the tenth and eleventh centuries pasture lands increased, probably due to the pressure exerted by local communities (Martín Viso & Blanco González 2016). In the Cantabrian Mountains, husbandry regimes echoing prehistoric grazing practices intensified in the early medieval period as new settlement patterns and economic orientations developed (Fernández Mier 2016). On both sides of the modern Spanish-Portuguese border, archaeological studies have unveiled the existence at different times throughout the period of local communities integrated into small-scale socioeconomic and political networks (Martín Viso et al. 2017; Tente 2020). Similarly, in Álava, extensification and diversification of farming practice in the context of a major restructuration of settlement patterns is apparent from the sixth century onwards, probably revealing the farming strategies of local, relatively self-sufficient peasant communities (Quirós Castillo 2020). Evidence of local forms of collective action – even if responding to external pressures – is provided by excavated systems of agricultural terraces both there and in Galicia (Ballesteros Arias & Blanco-Rotea 2009; Quirós & Nicosia 2019). Ultimately, then, during this period agrarian spaces throughout NW Iberia underwent major transformations in which the productive strategies of local actors gained weight (Quirós Castillo & Tejerizo-García 2021). In the inland, local and supra-local territories developed that were defined by shared access to natural resources, combined with other forms of collective action and institutions such as territorial assemblies and small-scale market exchange (Martín Viso 2020b; Vigil-Escalera Guirado 2019). By the ninth century we have strong written evidence for territorially-based, socially-cohesive communities acting collectively at a local and a supra-local scale (Wickham 2008), and evidence for collective action and local institutions transpires in later records through references to local groups, communities, and councils (Carvajal Castro 2020: 287–289).

By the second half of the ninth century, and most notably during the tenth century, major socioeconomic and political changes become apparent. Larger areas were integrated into the kingdoms of Asturias and Pamplona, which by the mid tenth century nominally controlled most of NW Iberia (Carvajal Castro 2017a; Larrea 1998). Lay aristocrats and religious houses enlarged their patrimonies, which they partly did through the acquisition of commons. Already by the ninth and tenth centuries, some monasteries sought to articulate long-distance transhumance routes through the acquisition of pasture lands in low-lying and mountain areas – livestock was central to monastic economies (Mínguez 1980; Pascua Echegaray 2011) –, and the pressure on commons would later increase as other actors, including not only lay aristocrats and monasteries but also local elites and councils, became involved in livestock rearing and the commercialisation of livestock production (Pastor 1970). Differences in access to commons marked social inequality in local societies (Escalona 2001), and control over commons was instrumental in the development of lordship and political authority (Carvajal Castro 2017a: 99–111; Martín Viso 2020a). Overall, pressure from lay and ecclesiastical elites became a significant – though not exclusive – driver behind changes in agrarian landscapes at the time (Fernández Fernández 2017; Fernández Mier et al. 2013; Quirós Castillo 2012; Quirós Castillo & Olazabal 2019).

The transformations occurred between the ninth and the eleventh centuries are illuminated by a large corpus of charters comprising 8794 records before AD 1099 (Table 1), most of which have been preserved in ecclesiastical archives.3 The great majority are records of land transactions but there is a significant proportion of dispute records – 1039 before AD 1099. Charters survive in large numbers from the tenth century onwards, which reflects the accumulation of land in the hands of lay aristocrats and religious houses – most notably monasteries, and also cathedrals –, and also the fact that most charters have been preserved in the archives of some of the latter. Many were copied in cartularies and single-sheets in response to later patrimonial and political interests, and were manipulated as a result – forgeries were also produced. Fortunately, contemporary and near contemporary records in parchment survive in significant numbers, which has allowed scholars to study scribal practice at the time and to assess how texts were modified by later copyists (Fernández Flórez 2004). There is also a significant amount of lay charters, many of which were probably drafted by local priests, and a number of lay archives have been preserved as part of some ecclesiastical archives (Kosto 2013), which provides a window on scribal and archival practice beyond the realm of the main monasteries. Recent research has further delved into the rationales that guided the preservation of charters and the compilation of cartularies in later centuries (Escalona & Sirantoine 2013). We thus have the empirical and methodological means to confront, even if partially, the monastic bias of the corpus, and to better evaluate the scope of the conclusions that can be drawn from its analysis.

Table 1

Chronological and regional distribution of charters for NW Iberia before AD 1099. Numbers of judicial records are indicated in brackets. Data: PRJ (http://prj.csic.es/) [Date accessed: 25/05/2021].

| CASTILE | LEóN4 | GALICIA | NAVARRE | PORTUGAL | TOTAL (PER 50-YEAR SPAN) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 700–749 | 0(0) | 0(0) | 3(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 3(0) |

| 750–799 | 0(0) | 5(0) | 8(0) | 1(0) | 0(0) | 14(0) |

| 800–849 | 6(0) | 13(1) | 14(1) | 5(0) | 1(0) | 39(2) |

| 850–899 | 8(1) | 49(4) | 62(14) | 14(1) | 6(2) | 139(22) |

| 900–949 | 104(12) | 488(30) | 216(28) | 65(3) | 55(12) | 928(85) |

| 950–999 | 238(11) | 876(83) | 341(65) | 83(2) | 144(16) | 1682(177) |

| 1000–1049 | 175(12) | 1077(171) | 314(88) | 229(12) | 237(61) | 2032(344) |

| 1050–1099 | 462(25) | 1401(146) | 330(68) | 983(60) | 781(110) | 3957(409) |

| Total (per region) | 993(61) | 3909(435) | 1288(264) | 1380(78) | 1224(201) | |

| Total n. of charters | 8794(1039) | |||||

The study of the commons faces more specific concerns. Most recorded transactions concern individual or family holdings and leave most collective dimensions of social life in the shadow. Nonetheless, it is clear from the appurtenance clauses, however formulaic, with which individual holdings are described in the charters that households shared access to certain resources within their local and supra-local territories, such as waters, woods and pasture lands (Larrea 2008: 186–188).5 Such clauses are attested all throughout NW Iberia, from the coast to the inland, in low-lying and mountainous areas. The provisions of the Fuero de León, issued in 1017, associate vicinity and use rights. In this, they are consistent with the chartes – and indeed a number of later charters refer to the Fuero on this matter (Estepa Díez 2012). Theoretically, shared resources could be used individually or by individual families (cf. Bonaldes Cortés 2007; Narbarte et al. 2021; Stagno 2017), though this does not mean that there were no shared notions and norms regulating their use (Sánchez León 2007). In eastern Castile, La Rioja, and Navarre, charters sometimes include information about the rules that regulated intercommoning in certain pasture lands (Larrea 2007b). Evidence for collective work is rare but not absent. In 940, the inhabitants of Villambrosa (Castile), gathered at the behest of Bishop Diego to clear a land (Larrea 2007a: 333). The intervention of the bishop and the fact that the land was cleared on behalf of a local church should not lead us to downplay the relevance of collective action and local institutions. Seigneurial domination over commons was not incompatible with local collective arrangements (Carvajal Castro 2017c; Gómez Gómez & Martín Viso 2021; Justo Sánchez & Martín Viso 2020), and lay aristocrats and monasteries could mediate collective action and institutions in some localities (Davies 2016: 219–226).

Some terms are known to identify commons, or at least collectively held resources. That, for example, is the case of serna, which designates fields seemingly cultivated individually in strips but held or managed collectively. Sernas were once thought to be newly ploughed lands in marginal areas, and were interpreted as an expression of agricultural expansion (Botella Pombo 1988; García de Cortázar 1980). More recent research has shown that many were deeply integrated into local agrarian landscapes and practice (Carvajal Castro 2017c; Gómez Gómez & Martín Viso 2021), while a more profound understanding of temporary cultivation in the wastelands has challenged linear narratives of agricultural growth (Larrea 2015). Access to water was also organised in shares, and related infrastructures such as mills and canals were held in common (Davies 2012), even if use was individually realised and shares could be alienated. For example, a man called Ordoño Adefónsiz granted the monastery of Piasca his turn to use a mill on Wednesdays (Mínguez 1976: doc. 305, AD 980). Other types of commons are also identified in the record, such as the orchards and flax fields owned by the council of Marialba (León) (Sáez 1987: doc. 184, AD 944) or the salt pans that the people of Salnés (Galicia) exploited collectively – even if under lordly control (Sáez & González de la Peña 2004, doc. 59, AD 956). The amount of information available is allowing for significant database analyses of the different types of commons recorded, their geographical and chronological distribution, their position in relation to other known features of the local landscapes, as well as of how different actors related to and engaged with them.6

Finally, disputes over the appropriation and management of collectively held resources provide fundamental information about commons (Pastor, 1980; Carvajal Castro et al. 2020).7 Most dispute records were produced by religious houses and ecclesiastics on their own behalf or on behalf of lay aristocrats to account either for their victories in court or for the benefits they obtained from the exercise of justice. They thus offer a partial and partisan view of those conflicts. Nonetheless, they are sufficiently diverse (Alfonso 2013; Davies 2016) and our understanding of the workings of justice (Davies 2016) and of the strategies and discourses of the disputing parties (Alfonso 1997a, 2004, 2007) is sufficiently well-developed to allow us to see through the aristocratic and ecclesiastical biases.

Avenues for Dialogue

The extant sources do not provide empirical grounds to engage with historiographical debates on the commons such as those sparked by E. Ostrom’s (1990: 88–102) ‘design principles’ on issues such as their sustainability (De Moor et al. 2002), success (De Keyzer 2018), and resilience (Curtis 2013). However, critical institutional analysis provides a number of avenues for dialogue, particularly with regards to the multifunctional, socially embedded nature of institutions and the weight of social inequalities and power relations in their configuration and functioning; the role of conflict in the definition of norms and their transformation over time; and the discursive practices aimed at legitimising specific institutional arrangements (Cleaver 2012; Cleaver & de Koning 2015).

Commons, Peasants, and Lords

One of the merits of De Moor’s (2008, 2015) ‘silent revolution’ model was to link the development of the commons to the broader socioeconomic transformations associated to the development of market economies. To do justice to this approach, if we are to admit that commons might have been more relevant in earlier periods than has often been acknowledged, and also wish to establish both fruitful historical comparisons and a more comprehensive understanding of long-term transformations, we must then conceptualise and analyse the role of commons in the socioeconomic systems dominant in Europe in the early Middle Ages.

Feudalism readily comes to mind, though at earlier stages a peasant mode of production may have prevailed in those regions that largely escaped seigneurial and state control, including some in NW Iberia. As defined by C. Wickham (2005: 536–537), the peasant mode of production would characterise situations in which producers do not give surplus – at least not systematically – to landowners or lords. It identifies the individual household as the basic production unit, considering the ties between individual units as resulting from mutual support materialised at the level of goods exchange. The possibility of whole villages collaborating in production is contemplated but dismissed as rare. The possibility that local collective institutions, even scarcely formalised ones, could regulate access and the use of certain natural resources and thus affect productive practices is not considered.

The peasant mode of production is a useful heuristic tool but needs to be qualified (Tejerizo-García 2020). In as much as peasants relied on mixed-farming which, in turn, depended upon the use of shared resources, we must at least contemplate the possibility that agrarian production and the reproduction of peasant societies — both individual households and larger groups — were based on a variety of practices combining the exploitation of individual holdings and natural resources whose use was collectively regulated, even if individually realised depending on the specific needs of each peasant family (Chayanov 1966). On this basis, produce, in whatever form – such as the different ‘funds’ defined by E. Wolf (1966) – should be considered as the outcome of mixed practices bounding different activities and resources together. For example, seasonal pasturing could forge a link between cultivated lands and common pasture, with livestock providing foodstuff but also manuring and traction power. Similarly, common woods would have been a source of fuel and building material for each individual household.

One of such funds, rent, remains central in definitions of feudalism in socioeconomic terms. Feudal relations of production are usually identified with landowners and lords coercively taking rent or tribute from tenants (Bloch 1949: 610; Duby 1953: 643; Haldon 1993; Wickham 2005: 535–536). The underlying assumption is that rent derived from agricultural production in holdings worked individually by peasants or peasant families. It is also admitted, though, that this need not entail direct control over labour processes (Wickham 2000). The fact that the definition is not restrictive in that regard allows us to think of rent not just as the direct outcome of agricultural production, as if this was detached from other productive activities, but rather as part of the outcome of intricate labour processes combining multiple resources and forms of appropriation and exploitation.

Moreover, lordship was not necessarily based on land ownership. It could adopt other forms, including extensive domination over multifunctional landscapes from which a variety of products could be exacted as tribute (Faith 2009). In this regard, the commons could be instrumental in facilitating lordly exactions (cf. Bhaduri 1991). Also, lordly control over commons could constrain the capacity of peasant units to make use of resources that were central for their reproduction in economic, political, and symbolic terms (Pascua Echegaray 2011; Sandström et al. 2017). Such control can be regarded as one of the basis of seigneurial and royal domination. At the same time, acquiring the capacity to grant access to particular resources could enhance the authority of lords and kings (Martín Viso 2020a; cf. Sikor & Lund 2009), which was one ways in which commons fed directly into polity building processes. Ultimately, then, there is room for including the commons into a broader definition of the feudal relations of production (Banaji 2010).

Commons and Property

In both the peasant and the feudal modes of production, therefore, the commons can be regarded as central to agrarian production, to the biological and social reproduction of individual peasant households, and to the articulation and reproduction of social relations of production. This last aspect begs a further question: how were relationships between different, potentially competing actors articulated around commons? Accounts on NW Iberia to date have tended to focus on conflicts over the ownership of commons (Pastor 1980) but more nuance can be achieved by introducing further theoretical notions from commons and property scholars.

Early medieval historians, including those working on early medieval NW Iberia, have long acknowledged that different actors could have different capacities with regards to land. Proprietas, as ownership, is often distinguished from possessio, as the effective capacity to make use of it (Sánchez-Albornoz 1976: 635–639; cf. De Moor et al. 2002: 23). The distinction is not merely heuristic: dispute records from NW Iberia show that these two dimensions were distinguished as the matter of conflict by actors at the time (Alfonso 1997b). For the commons, however, a more complex analytical framework must be considered, as other types of actors and capacities need to be accounted for. Indeed, based on later evidence, we should expect disputes to focus not on the commons as such, but rather on the specific capacities claimed by different actors (cf. Warde 2002: 200). To address this issue, I will here assume E. Schlager and E. Ostrom’s (1992) conceptualisation of property as a point of departure. They define property as a bundle of rights comprising access, withdrawal, management, exclusion, and alienation. I will here characterise them as ‘capacities’ rather than ‘rights’ as a means to account for the fact that they were not – or not only – normatively defined but rather dependant on the relationships and balances of forces between different actors (Galik & Jagger 2015; Ribot & Peluso 2003).

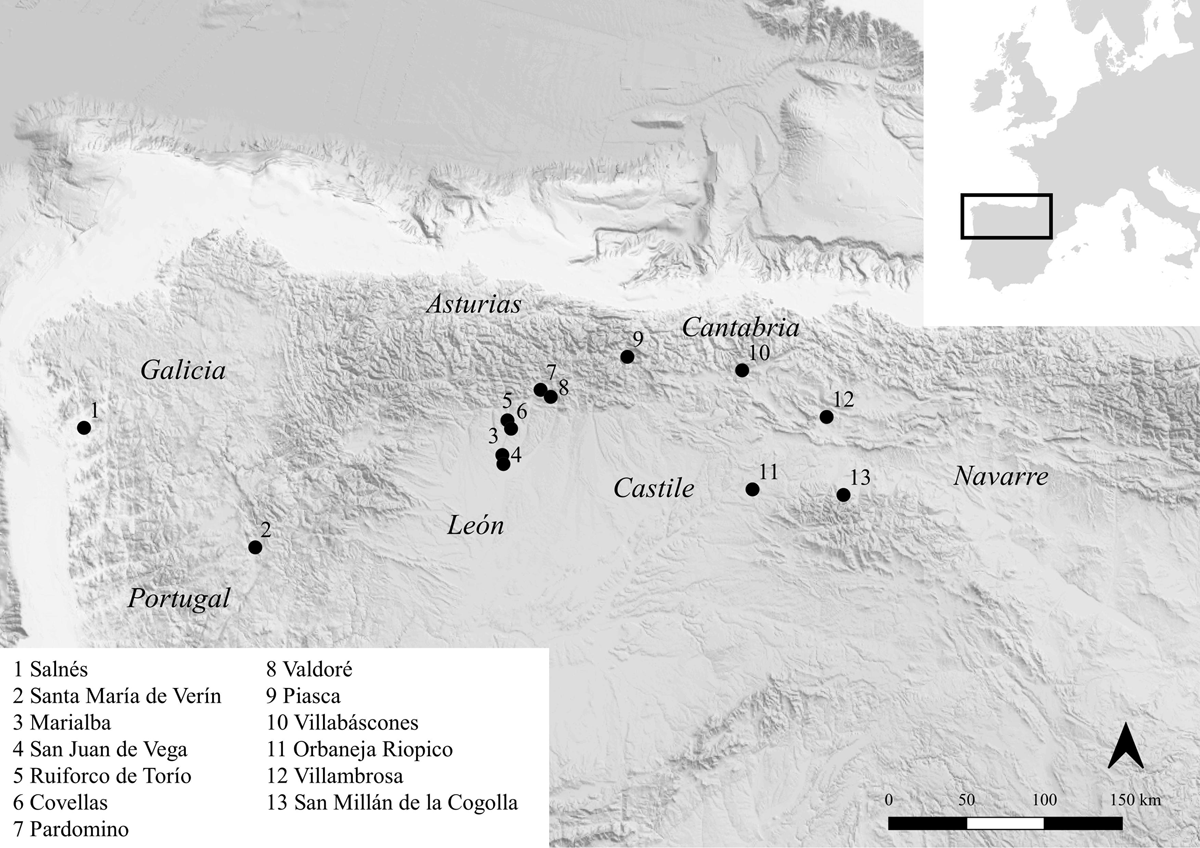

The applicability of this analytical framework can be evidenced through the analysis of a series of case studies (Figure 1). A case in point is a dispute between the monks of Pardomino and a series of local communities from their surroundings over a vast mountain area north of León (Sáez 1987: doc. 184, AD 944). Both parties claimed full ownership, and the dispute was settled by dividing the area into two halves, though further conditions were introduced that affected aspects other than access, exclusion and alienation. The local communities’ withdrawal and management capacities were limited, as they were not allowed to plough lands and use the existing mills or build new ones in their designated half. The contingency of such arrangements – in as much as they were dependant on the specific balance of forces between the implicated parties at any given time – is demonstrated by a later charter that shows that at least some among the locals continued to plough lands in that area (Sáez & Sáez 1987: doc. 290, AD 955). Access and management restrictions are usually central in cases presented as land invasions, as in that of the two men who were accused of breaching into the lands of the monastery of Santa Marina de Valdoré and clearing a field (Fernández Flórez & Herrero de la Fuente 1999: doc. 43, AD 997). A woman called Trudildi, for her part, had the limits of Santa María (Verín, Galicia) perambulated in order to assert her control over lands that the inhabitants of a number of nearby localities were using (Andrade et al. 1995, doc. 95, AD 950/951). Other cases show that withdrawal capacities could be preserved even if lands were alienated, as by reserving the capacity to collect wood (Sáez & Sáez 1987: doc. 285, AD 955). Correspondingly, unauthorised collection could be fined (Ruiz Asencio 1987: doc. 590, AD 999).

Figure 1

Location of cases cited in the text. Map created using QGIS. Basemap: IGN.

Importantly, restrictions were not only imposed from above, as local individuals and groups could effectively resist seigneurial impositions and even prevent lords from realising their claims (Carvajal Castro 2019). Social differences and inequalities between local actors also informed individual capacities over natural resources. A telling case can be found in the charters from Covellas (León). In this locality, there were several water springs. While the capacity to withdraw water was shared, a local couple, Álvaro and María, seemingly enjoyed control over access to at least some springs. In 942, a woman sold them her share in a spring called Fonte Incalata in exchange for access to another spring in a place called Plano and the capacity to withdraw as much water as two carts could take (Sáez 1987: doc. 151, AD 942). Key for understanding this transaction is the realisation that Álvaro and María may have also controlled access to Fonte Incalata. Some years before they had granted the monks of Abellar the capacity to take their livestock to the spring and withdraw water for the monks’ own needs (Sáez 1987: doc. 94, AD 932). Ultimately, then, Álvaro and María resorted to their control over springs in order to advance their position vis-à-vis their neighbours and to negotiate their relationship with a more powerful actor.

Regulations and Power Relations

Dispute records show how power relations and conflict between actors of very unequal social standing – as opposed to intra-community conflicts (cf. De Keyzer 2018: 99) – shaped normative arrangements over access to and the use of certain resources and infrastructures. This is particularly apparent in a number of disputes revolving around the use of water to feed mills. During the first third of the tenth century, a group of heredes8 from San Juan de Vega (León), held such a dispute with the monastery of Santiago de Valdevimbre (Carvajal Castro et al. 2020: 153–154; Sáez 1987: doc. 128, AD 938). The monks challenged the heredes’ right to access the channel feeding the mills, arguing that the latter had ceased to use it. The heredes replied that they had enjoyed continuous access for generations and that it had only been fortuitously interrupted as a result of a flood. The monks then challenged the heredes’ withdrawal capacity, arguing that the latter were depriving them of the water they were entitled to. Measurements made by royal delegates proved the monks wrong. In spite of this, the monastery was granted the capacity to request work from the heredes to maintain the dam. Ultimately, this long-standing dispute did not alter the parties access and withdrawal capacities, but introduced changes in management rules that reflected and also affected the unequal power relations between them. Similarly, as a result of a dispute between the religious community of San Martín de Villabáscones (Castile) and the local council, the members of the latter were granted the capacity to withdraw a certain amount of water from a canal on the condition that they would regularly clean it (Martínez Díez 1998: doc. 89, AD 956).

Multi-functionality, Institutional Bricolage, and Discourse

As in the case of Villabáscones, in some regions, particularly in Castile and León, local councils regulated the appropriation and use of certain natural resources, and at the same time were central to the definition of local communities and identities. The charters tell us little about the composition of these local councils, other that it reflected social differences and inequalities at the local level. They served multiple purposes, including the formalisation of land transactions, the exercise of justice, and religious practice, among others (Carvajal Castro 2017b; Escalona 2019). Local councils thus operated within complex, interrelated normative assemblages (Santos 1987). The last avenue for dialogue here considered is the recognition of the multi-functional nature of these institutions, and in relation to this the analysis of the practices of bricolage by means of which different actors articulated discourses in order to legitimise their claims over commons (Cleaver 2012).

That was the case in the valley of Orbaneja (Castile). The valley hosted several local communities. The inhabitants of one of them were dependants of the monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña, which by the mid-eleventh century was apparently exploiting this position in order to graze its livestock in the valley pastures. The other local communities reacted by denying Cardeña’s vassals the capacity to graze livestock in the common pastures. The discussion, however, was not only about grazing. The record reveals that it was intertwined with further arguments about the duties owed by the locals, such as military obligations, which was in turn related to issues of status – military activity was an attribute of free, non-aristocratic individuals; the monastery’s dependants were exempt of such obligations, this being a trait of their serfdom. The capacity to use the common pastures was thus one among an integrated assemblage of duties and obligations that defined inclusion in, and exclusion from, the valley community, and with it identity and status (Escalona 2006a: 89–90). An analogous case in point relates to murders and their associated penalties. Local councils were liable for murders committed in their local territories when the perpetrators could not be identified. This entailed the payment of a fine called homicidium. Assuming the payment of the homicidium could be wielded as a means to claim associated capacities in the territory at stake, as we know that the monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla did in at least two occasions in the late eleventh century (Larrea 2007b; see also Escalona Forthcoming 2021).

Crucially, the capacities that different actors could claim were not necessarily defined within the same normative frameworks. For example, it has been observed that, in certain contexts, local groups resorted to ploughing, grazing cattle, and collecting fruits and woods to assert their land claims in the face of elite actors claiming title rights and land delimitations (Larrea Forthcoming 2021). The discourses articulated to legitimate the outcome of land disputes and conflicts over commons did not necessarily entail the imposition of one particular normative framework over another. For example, in 931 in León, a dispute over certain lands arose between the inhabitants of Manzaneda de Torío and Garrafe de Torío, on the one hand, and the monks of San Julián de Ruiforco de Torío, on the other. The people from Manzaneda and Garrafe argued that they actually worked and exploited those lands, while the monks argued that they had royal diplomas granting them ownership. To settle the issue, the royal delegates made an inquest among the local elders. The monks won the case, but the legitimisation of their claims, as it emerged from the dispute, did not only rely on the royal grants they had. It also integrated the knowledge gathered through the inquest from the testimony of the local elders (Sáez 1987: doc. 89, AD 931) This speaks of the monks’ need to integrate local knowledge and work their way through the local normative framework as a means to realise their more abstract claims, those deriving from royal grants.

Conclusion

This paper has argued for the need to integrate the early medieval centuries into broader debates on historical commons, and has identified a number of avenues for dialogue with historians working on later periods and other common scholars. It has focused on NW Iberia to show that a proper historical understanding of the commons in this region needs to situate them against the transformations triggered by the collapse of the Roman Empire. It has also argued that the written sources from NW Iberia provide sufficient evidence on the centrality of commons in local and supra-local territories and in the articulation of social relationships between actors at the local and the supra-local scales, and attest to the multi-layered nature of commons and other local institutions. It has argued that while rule-centred approaches cannot be easily applied, a critical institutional approach, with its concern for socioeconomic and power inequalities, conflict, and discourses, may enhance our understanding of early medieval commons. The processes documented for NW Iberia have parallels elsewhere in Europe, albeit at different times during the early Middle Ages, and the written sources from other European regions provide comparable evidence. The approach here outlined could thus frame a broader comparative approach to Western Europe. The paper also suggests that such an approach can frame comparative analysis with later historical commons, and provide common ground for further theoretical debates with commons scholars.

The empirical relevance of early medieval dispute records must also be highlighted. The written sources from early medieval NW Iberia seem particularly well-suited to further our understanding of how conflicts shaped and transformed commons in feudal contexts. Conflicts allow for contextual analyses of the commons in dispute; of the competing actors, the relationships between them, and their strategies and discourses; and of the outcomes of the disputes (Ratner et al., 2013; Ratner et al. 2017). From this perspective, the role of conflict in the reproduction and transformation of the commons and other local institutional arrangements can be assessed (cf. Coleman & Mwangi 2015; Knight 1992; Ogilvie 2007). More particularly, and with regards to more specific historiographical concerns, conflicts operate as a prism through which peasant agency and disputing strategies and discourses can be analysed. A shared theoretical framework has the potential to develop further comparative work on peasant forms of collective action from a broader historical perspective (McDonagh & Griffin 2016).

Notes

[1] I follow R. Chapman (2003) in his theoretical characterization of social complexity.

[2] Most relevant for the early medieval period are the contributions made in the context of two research projects, “Local spaces and social complexity: the medieval roots of a twentieth-century debate (ELCOS)” (Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, Spain, Ref. HAR2016-76094-C4-1-R), led by Margarita Fernández Mier; and “Formación y dinámica de los espacios comunales ganaderos en el Noroeste de la península ibérica medieval: paisajes e identidades sociales en perspectiva comparada” (Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, Spain, Ref. HAR2016-76094-C4-4-R), led by Iñaki Martín Viso and Pablo C. Díaz. As in other European regions, the archaeology of the commons, linked to the archaeology of mountain areas, has become a thriving field of research, though the focus remains on later centuries (e.g.: Fernández Mier & Quirós 2015; Narbarte et al. 2021; Stagno 2017).

[3] The surviving narrative sources and annals are few and have little bearing on the issue of commons. Laws are available for the Visigothic kingdom but cannot be taken as evidence of practice on the ground due to their level of generality and their prescriptive nature. Importantly, though, Visigothic law influenced how property was conceptualised and disputes were pursued in later centuries (Collins 1985; 1986), and thus needs to be considered when analysing how land claims were formulated. No laws were passed before the promulgation of the Fuero de León in 1017 (see below).

[5] To quote but one example: ‘Placuit nobis […] ut vinderemus vobis hereditate nostra propria […] terras, ortales, vineas, paludes, cortes, casas et sua aiacentia, nostra porcione in montes, in fontes’ (‘We agreed […] to sell you our hereditas […] arable lands, orchards, vineyards, marshes, farms, houses with their appurtenances, our share in pastures and in springs’) (Mínguez 1976, doc. 110, AD 948). The term hereditas (lit. inheritance) refers both to inherited holdings and to the kind of property that granted community membership and access to commons.

[6] This is the approach of the project “Formación y dinámica de los espacios comunales” (see n. 2).

[7] Importantly for broader comparative purposes, they have parallels elsewhere in Europe (Wickham 2003, 2012).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship: Project CLAIMS (Grant agreement ID: 793095). The author is a member of the Research Group Grupo de Investigación en Arqueología Medieval, Patrimonialización y Paisajes Culturales (Gobierno Vasco, código IT1193–19). An earlier version was presented at the VIII Seminario de la Sociedad de Estudios de Historia Agraria (SEHA). I wish to thank the organisers for giving me the opportunity to discuss my work, and more particularly José-Miguel Lana Berasain, Julio Escalona, Isabel Alfonso, as well as the anonymous reviewers of the article, for engaging with the text and providing useful comments, suggestions, and critiques.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.