Table 1

Systematic search.

| CATEGORY | KEYWORDS |

|---|---|

| Citizen science | Citizen science, participatory science, community science, community engagement, community participation, public science |

| Mosquito surveillance | Mosquito, mosquito surveillance, mosquito monitoring, mosquito-borne diseases, vector, vector mosquito, infectious diseases, dengue, malaria, zika, arbovirus |

| Time frame | 2000–March 2021 |

| Language | English |

| Database | Medline, Scopus, PubMed, web of Science, Google Scholar, grey literature. |

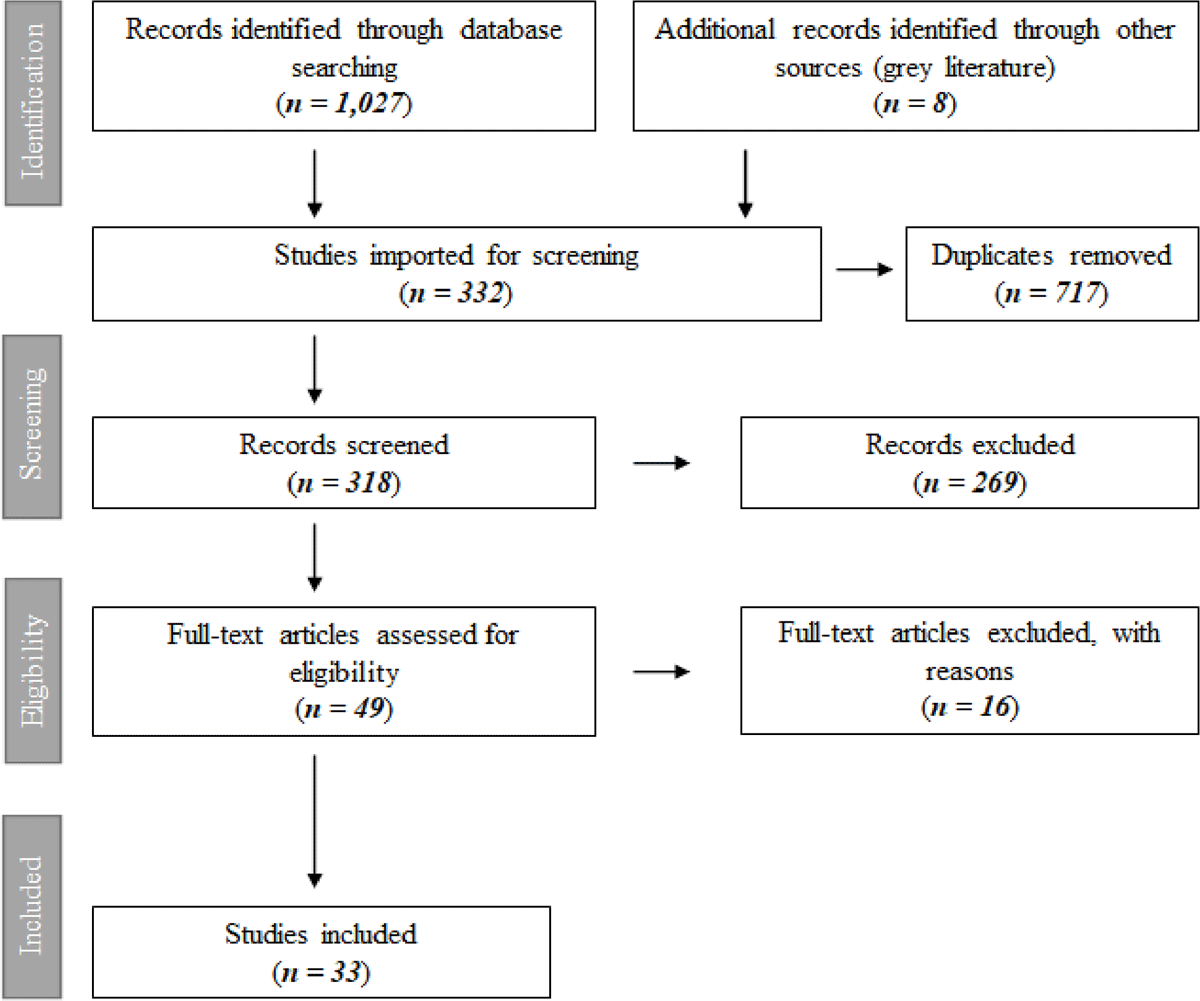

Figure 1

PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews flow diagram showing the scoping review process for citizen science based mosquito surveillance programs.

Table 2

Citizen science mosquito surveillance programs worldwide.

| SURVEILLANCE SYSTEM TITLE | COUNTRY (STATE/CITY) | DURATION | PARTICIPANTS | TARGET MOSQUITO/S | SPECIMEN ASSESSED | SPECIMEN COLLECTION, REPORTING AND ANALYSIS METHODS | REF | URL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | a Mosquito Alert (previously ‘Atrapa el Tigre!’) | Spain | 2013/14 (Atrapa el Tigre!) and 2016–ongoing (Mosquito Alert) | Initially primary school students, later the general public | 2013: Ae. albopictus; 2014–2019: Ae. albopictus, Ae. aegypti; | Adult mosquito | Using a smartphone application, participants sent geo-referenced images of target mosquito species to a research team. Received images were independently evaluated by experts and public health response measure mounted, depending on assessment findings. | Bartemeus et al. 2018, Hernandez et al. 2017, Pernat et al. 2021a | mosquitoalert.com |

| 2 | a Mozzie Monitors | Australia (South Australia) | 2018–May 2019 | General public | Non-specific | Adult mosquito | Participants were provided with a GAT trap for collection of mosquitos in urban environments. Participants photograph their catch and email the image to a research team for identifications. Participants reported data fortnightly. | Braz Sousa et al. 2020 | mozziemonitors.com |

| 3 | a Zika Mozzie Seekers | Australia (Queensland) | 2017–ongoing | General public | Aedes mosquitoes | Mosquito eggs | Participants are asked to set up DIY backyard mosquito egg traps, collect the eggs and send them in for molecular analysis. The program uses the PCR technique to detect traces of DNA of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. | Montgomery et al. 2017, Montgomery et al. 2020 | metrosouth.health.qld.gov.au/zika-mozzie-seeker |

| 4 | a Mozzie AR Toolkit | Australia (Queensland) | 2019–ongoing | Primary school students | Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti | Breeding sites | This program targets primary School children from Brisbane, QLD, Australia, using Augmented Reality (AR) as an interactive experience to encourage students to identify and manage mosquito breeding sites. | Seevinck et al. 2019, Seevinck et al. 2020 | mozziescience.wordpress.com/2020/08/03/mozzieart/ |

| 5 | a STEM Champion Mozzie Hunters | Australia | 2019–ongoing | Secondary School students | Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti | Eggs | Students construct biodegradable traps to collect eggs of urban mosquitoes. Then, they learn how to extract the DNA and use open-source and affordable molecular technologies (real-time PCR) to identify the presence of exotic mosquitoes DNA in the eggs. | Seevinck et al. 2020 | mozziescience.wordpress.com/2020/08/06/scmh/ |

| 6 | a Honiara Citizen Science | Solomon Islands | 2019 | General public | Non-specific | Adult mosquitoes | Volunteers attended a training workshop and were provided BG-Sentinel traps to collect and type mosquitoes over an 8-week period of data collection. They also received a magnifying glass and a pictorial mosquito identification card. Participants sent SMS to a central authority to report count data. | Craig et al. 2021 | |

| 7 | a ZanzaMapp | Italy | 2016–2018 | General public | Non-specific | Adult mosquito nuisance | Participants use a mobile phone app, ZanzaMapp, to share their perceptions of mosquito abundance and nuisance in Italy. Users share their records’ GPS locations and answer four questions regarding the perceived presence, abundance, and nuisance of mosquitoes. | Caputo et al. 2020 | www.zanzamapp.it/ |

| 8 | a The North American Mosquito Project citizenscience.us | USA and Canada | 2011–2012, 2014–2015 | Mosquito control professionals, and later the general public | Not reported | Adult mosquito | Citizen participants were provided with traps and attractants, and asked to send the unsorted trap catch to a research team for identification. | Cohnstaedt et al. 2016b | |

| 9 | a The Invasive Mosquito Project (evolved from the North American Mosquito Project) | USA | 2016–ongoing | High school students | Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopticus | Adult mosquito; mosquito eggs | Students placed germination paper in prepared containers to collect eggs laid by container-dwelling mosquitoes. Dried paper (with eggs attached) was taken by the student to school, where quantitative and qualitative observations were made and recorded. In addition, students (under teacher supervision) were encouraged to hatch a portion of the eggs and identify mosquito species using a picture key provided. Further, to confirm adult mosquito identification, students shipped specimens to the US Department of Agriculture (or a local or regional mosquito control partner). | Cohnstaedt et al. 2016a | Citizenscience.us |

| 10 | a Mosquito Stoppers | USA (West Baltimore) | 2014–2015 | General public | Ae. albopictus | Adult mosquito | Participants completed up to four data collection tasks (i.e., questionnaires) designed to quantify Ae. albopictus habitat and population levels, and mosquito nuisance in their yards. Data was reported monthly for 6-weeks. | Jordan et al. 2017 | baltimoremosquitoes.weebly.com |

| 11 | a The Great Arizona Mosquito Hunt | USA (Arizona) | 2015–2017 | Primary school students | Ae. aegypti | Mosquito eggs | Participants were provided with a kit that included instruction on how to make an ovitrap, germination paper, and alfalfa-based rabbit food to serve as an attractant. Participants set the trap and collected, dried, and mailed the germination paper (with mosquito eggs attached) to a research team. Received samples were inspected by an entomologist to identify Aedes eggs. | Tarter et al. 2019 | |

| 12 | a iMoustique® | France | 2013 | General public | General, focusing on Ae. albopictus | Adult mosquito | iMoustique® is a smartphone app used to share information on mosquito presence. The app provided a simple three-step determination key to help people identify if the observed specimen is a mosquito. Users shared georeferenced photos of the observed mosquitoes. | Kampen et al. 2015 | www.eidatlantique.eu |

| 13 | a The Muckenatlas | Germany | 2012-Ongoing | General public | Non-specific | Adult mosquito | Participants are required to capture resting mosquitoes using a closable container and to post killed mosquitoes with a completed questionnaire (that is available online) to a research team where they are identified in a laboratory using either morphologic or genetic methods. Identification of invasive species of interest are investigated and enhanced surveillance implemented, if required. | Pernat et al. 2021a, Pernat et al. 2021b, Walther and Kampen 2017, Werner et al. 2020 | Muechenatlas.de |

| 14 | a The Muggenradar | Netherlands | 2014 | General public | Non-specific | Adult mosquitos | Via a web-questionnaire, participants provided information on their experience with nuisance mosquitos, including the time/date and location of an incident. Participants were given the opportunity to submit a mosquito specimen for identification. Received samples were genetically analysed; results were not reported. | Kampen et al. 2015 | Muggenradar.nl |

| 15 | a Mosquito WEB | Portugal | 2014-ongoing | General public | Non-specific | Adult mosquito | Participants collect mosquitos in the environment and post them, together with basic information about the insect’s collection location, to a research team who identified the sample using morphological and/or molecular means. | Kampen et al. 2015 | Mosquitoweb.pt |

| 16 | a TopaDengue | Paraguay | 2018–2019 | General public | Ae. aegypti | Larvae, pupae and breeding sites | Community volunteers visited houses in their neighbourhood every week in specific months (dry and rainy) to inspect the presence of larvae and pupae Aedes aegypti and the type of container they were breeding. Volunteers used both paper and digital technologies to report the outcomes to researchers. As digital technology, they used the DengueChat interface to share data of breeding and entomological status. | Parra et al. 2020 | |

| 17 | a Monitoring alien mosquitoes of the genus Aedes in Austria | Austria | 2017 | General public | Aedes mosquitoes | Mosquito eggs | Citizen scientists used provided ovitraps to monitor mosquito oviposition in their houses. They sent the samples to researchers for species identification through morphology assessment. Researchers can use DNA extraction and PCR for identification as well. | Schoener et al. 2019 | |

| 18 | a GLOBE Observer | Wide geographic coverage/93 countries | 2016–ongoing | General public | Non-specific | Mosquito habitats/breeding sites | GLOBE Observer is an ongoing NASA-sponsored citizen science mobile application. Citizen scientists download the app, complete interactive training to learn how to use the tools, and share their mosquito breeding habitat photos. GPS information, time and date of each observation are shared. Participants also answer some questions about surface conditions and report numerical estimates of mosquito larvae. | Amos et al. 2020 | observer.globe.gov/get-data/mosquito-habitat-data |

| 19 | a Cit Sci in Rwanda* | Rwanda | 2018 | General public | Non-specific | Adult mosquitoes, malaria cases and mosquito nuisance | Volunteers were asked to report experienced mosquito nuisance and confirmed malaria cases in their houses. Additionally, the selected volunteers used passive mosquito traps to collect and submit collected specimens. More than 2,000 mosquitoes were collected throughout six months. | Murindahabi et al. 2019 | |

| 20 | a Abuzz | Worldwide | 2017–2018 | General public | Non-specific | Adult mosquitoes – wingbeats | People were encouraged to record sounds of mosquito wing beats by placing their mobile phone microphones near the flying mosquitoes. People referred to brochures to learn how to record the sounds more effectively. They can point their phones to mosquitoes on the wall (and make them fly), to flying mosquitoes, or even to mosquitoes trapped in a bottle and record the sounds from the bottle walls. Records are uploaded to the Abuzz project website. | Mukundarajan et al. 2017 | web.stanford.edu/group/prakash-lab/cgi-bin/mosquitofreq/how-you-can-help/record-mosquitoes/ |

| 21 | a Citizen Action through Science (Citizen AcTS) | USA | 2016–2017 | General public | Ae. albopictus | Adult mosquitoes | Citizen scientists purchased one or more Biogents-Sentinel (BGS) traps (Biogents, Regensburg, Germany) in their backyards to capture adult mosquitoes. The traps were operated for 24 h using 12 V rechargeable batteries. Trials included eight sampling events of 24 h each, over six weeks. Researchers counted and identified adult mosquitoes collected per trap. | Johnson et al. 2018 | |

| 22 | a Crowdsource for Mosquito Sampling* | USA, Canada (plus outgrouped samples received Europe and Asia) | 2011–2012 | General public | Ae. vexans or Cx. tarsalis | Adult mosquitoes | People were recruited by mail, email, phone and word of mouth, and were invited to collect and send samples of adult mosquitoes. Recruited people received sample vials, traps, alcohol, and prepaid mailers on request. Contacts sent more than 1,000 specimens from 40 different provinces and states in Canada and the USA and from some outgroups in Europe and Asia. | Maki and Cohnstaedt 2015 | |

| 23 | b Mo-Buzz | Sri Lanka (Colombo) | 2015-ongoing | General public | Ae. aegypti | Dengue-like illness symptom and breeding sites | Through the Mo-Buzz smart phone application, participants report dengue-like illness symptoms, knowledge of mosquito exposure/visible bites, perceived mosquito density, and/or post pictures of potential Aedes mosquito breeding sites. Data received is time-stamped and geotagged and sent to health authorities, thereby stimulating a public health action. | Lwin et al. 2016, Lwin et al. 2019 | |

| 24 | b Dengue Chat | Nicaragua, Mexico, Brazil, Paraguai, Colombia | 2015 | General public | Aedes mosquitoes | Mosquito breeding site | Dengue Chat crowdsources information from the public through a smartphone application. Participants report the location of suspected breeding sites and provide photographic evidence. Data are shared with other users through the app or web interface. Community members can engage with each other and exchange information about dengue and chikungunya risks. | Coloma et al. 2016 | www.denguechat.org |

| 25 | b Camino Verde | Nicaragua and Mexico | 2004–2012 | General public (supported by community leaders and facilitators, the “brigadistas”) | Aedes mosquitoes | Mosquito larvae and pupae | Activities were facilitated by community volunteer leaders who received training (Brigadistas). They visited houses in urban and rural areas, and checked for mosquito breeding sites and the presence of larvae and pupae. Schools, churches, shops, clubs and other organisations were engaged in the effort as well. Brigadistas reported findings to the Centro de Investigación de Enfermedades Tropicales (CIET, Centre for Investigation of Tropical Diseases) and the University of California, Berkeley. | Arostegui et al. 2017, Hernandez-Alvarez et al. 2017, Ledogar et al. 2017a, b, Morales-Perez et al. 2017 | caminoverde.ciet.org |

| 26 | b Lansaka Model | Thailand | 2014–2015 | General public (supported by a network of village volunteers) | Aedes mosquitoes | Mosquito larva | Household members inspected and recorded larvae in containers in- and outside their houses every day. The group leaders collated the data from village volunteers and provided it to the head of the village who provided the data to designated health authority. Data were entered it into an online database by the authority. Information derived from the data was reported back to the community through the network, and was advice on any public health action required. | Suwanbamrung 2018, Suwanbamrung et al. 2018 | |

| 27 | b Mosquito Reporting Scheme/Mosquito Watch | UK | 2005–2012 | Amateur and professional entomologists, museums and universities and the general public | Non-specific | Adult mosquitoes | Interested participants sent samples of mosquitoes causing a nuisance to the Public Health England (PHE) for identification. | Kampen et al. 2015 | |

| 28 | b Patio Limpio | Mexico | 2007 | Community leaders and the general public | Aedes mosquitoes | Breeding sites | Trained local residents (known as block activators) participated in community assemblies. Educational and informative materials were also distributed to the households during visits. More than 1,000 block activators received training, and they inspected more than 5,000 backyards. | Tapia-Conyer et al. 2012 | |

| 29 | b Intersectoral dengue control in Cuba* | Cuba | 2003–2005 | General public | Aedes mosquitoes | Breeding sites | From 2003 to 2005, informal leaders from existing community organizations participated in Community Working Groups (CWGs). These members visited the houses in their local areas, surveying backyards and water storage containers (with the presence of the households). They monitored the presence of container breeding sites and offered options to protect or eliminate the containers. | Sanchez et al. 2009 |

[i] a Citizen science–identified programs. b Community-based programs and/or interventions non-identified as citizen science in the published articles but considered as citizen science interventions in this review owing to participatory research. *No specific name for these programs/interventions.