Introduction

Education can be an effective tool for cultivating positive human-aquatic interactions and solutions to environmental crises (e.g., Ardoin et al. 2020). In particular, knowledge about oceans is highlighted as essential to environmental literacy (Freitas et al. 2024; NMEA 2025). Freshwater ecosystems share with marine ecosystems an urgent need for conservation, yet a criticism of both formal and informal environmental education includes insufficient teaching about freshwater (Fortner & Meyer 2000; Sammel et al. 2018). Freshwater, and the biodiversity it supports, are essential for life on earth (Lynch et al. 2023) but face substantial environmental stress from chemical and nutrient pollution, water and resource extraction, climate change, agriculture, and invasive species (Sayer et al. 2025). A major challenge is the interdisciplinary nature of aquatic resources—be they salt or freshwater—which often requires the application of the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities.

One approach to such complexity is vessel-based education (VBE), the hands-on acquisition of knowledge about oceans, lakes, and rivers through on-water, boat-based activities. VBE presents an optimal avenue to engage students in place-based exploration to gain environmental literacy and better understand the indivisible relationship between humans and water (Freitas et al. 2024; Morgan & Braungardt 2025). Its effective pedagogy is rooted in immersive, hands-on education about water resources (e.g., testing and interpreting water chemistry, identifying and analyzing biological samples, interpreting nautical charts and scientific graphs), which builds practical skills and environmental connections. Although some programs offer shore-based or ship-to-shore data sharing (e.g., Arthur et al. 2021), our paper focuses on the at-sea, experiential learning of VBE.

VBE programs differ in audience and time spent aboard vessels, and often take advantage of the historical, ecological, and economic significance of a region. At one extreme of duration, education-level, and geographic-range is the Sea Education Association (SEA), which offers semester-long VBE to undergraduates about the sustainability of marine ecosystems in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans (Freitas et al. 2024; Rowland & Kitchen-Meyer 2018). Exposing participants to another essential component of Earth’s hydrosphere, the R/V Lake Guardian (a US Environmental Protection Agency Research Vessel) operates week-long VBE programming for teachers and higher-education students on the five Laurentian Great Lakes (hereafter Great Lakes); these lakes contain about 20% of the world’s fresh surface water and 95% of the United States’ surface water (Hunnell et al. 2023). Most common, and at the other extreme of duration and education-level, are partial-day VBE programs for elementary and secondary students that operate in coastal and freshwater ecosystems, such as programming aboard the R/V Sloop Clearwater in the Hudson River (NY), the R/V Marcelle Melosira in Lake Champlain (VT), and the newly launched Sadie Ann in Lake Superior (WI). These programs aim to give young students initial research experiences at sea.

As VBE programs have individualized goals and unique approaches, we endeavored to determine if there were shared accolades and limitations for vessels operating freshwater VBE programs in the Northeastern USA and the Great Lakes—regions where lakes and rivers are integral to the landscape and human social systems. Despite the widespread occurrence of freshwater programs, a big-picture understanding of VBE as interdisciplinary, environmental education is lacking. Our paper synthesizes the wealth of VBE opportunities available to educators with the aims of (1) improving access to VBE, (2) providing targeted recommendations on the facilitation of VBE, and (3) increasing access to data about these collective VBE programs for use by policy makers, state agencies, and school districts. Our questions included: Who attends freshwater VBE programs? What topics are included during cruises? How are VBE programs funded? In addition, we conducted a case study with 13 years’ worth of archived data from Science on Seneca (SOS; NY, USA), a VBE operating for nearly 40 years in the Finger Lakes region of NY State. Our long-term demographic analysis of this program, coupled with teacher interviews, aimed to document the potential role of freshwater VBE in environmental education of aquatic resources.

Methods

Survey of Freshwater Vessel-Based Education (VBE)

In October 2024, we surveyed 24 vessels operating in the freshwaters of the Northeastern USA and Great Lakes that host VBE programs. These vessels were identified either directly by the authors given their fields of expertise or through internet searches. Keyword searches included “vessel-based education”, “floating classroom”, “shipboard education” as well as appropriate geographic regions and state. Although our list may not be exhaustive, it represents the vast majority of vessels with freshwater education programs in the Great Lakes and Northeast and excludes vessels exclusively operating research programs or marine education. A questionnaire was generated in Google Forms (see Appendix A for questions) and distributed to the main contact(s) of 20 different VBE programs (four of the programs were associated with two vessels). We received 19 responses; no response was received from the Dr. Robert Werner Research & Education Boat (Skaneateles, NY), which was identified from an internet search, and it is not included in our results.

Case Study of Science on Seneca

Demographic analysis

Science on Seneca (SOS) is an EPA-award-winning program operating through Hobart and William Smith Colleges (HWS), which provides middle and high school students with a multifaceted, field-based experience on Seneca Lake (NY). The SOS program was initiated in 1986 and runs aboard the 65-foot R/V William Scandling. After an in-depth training workshop with HWS faculty experts, secondary teachers lead their students through a half-day exploration of the lake, typically at three fixed monitoring locations with varying distance from the shore. Activities include plankton surveys and identification, lake sediment sampling, water clarity measurement, and water chemistry testing.

To evaluate the usage of the SOS program, participation data from 2010–2023 was analyzed. We examined the annual number of SOS cruises and participating student numbers, reporting autumn (September through November) and spring (March through May) cruises separately. The research vessel does not operate during winter conditions from late November through the middle of March. No SOS cruises occurred in 2020 due to COVID-19 precautions. Also excluded from the data is spring 2021 and autumn 2022 because the vessel was undergoing maintenance.

From SOS registration records, we identified grade level and class subject. Classes were organized into the subject areas of biology, chemistry, earth science, enrichment programs, environmental science and studies, middle school science, physics and physical science, and other. Classes were further subcategorized by class level (e.g., advanced, general, electives). The frequency of various class categories was determined by counting the number of times each course name within the category appeared in the entire data set from 2010–2023.

Using census data (NCES, n.d.) and official school websites, we gathered additional attributes about the schools, including school location and enrollment size. ArcGIS Online was used to create a GIS map for visualizing enrollment size and the distance between participating schools and the research vessel (Geneva, NY). School distance (in miles) was calculated in ArcGIS Online using the “Connect Origins to Destinations” feature, which measures or the shortest straight-line distance between the two locations.

Teacher interview procedure

To examine teachers’ perceptions of VBE, we conducted five individual teacher interviews and one group interview in the spring of 2024. For the individual interviews, a list was generated of teachers at public high schools who interacted with the SOS program (a collaborative and voluntary relationship). From this list, we selected teachers to interview who had an academic focus in biology and/or environmental science, since those were the subject areas with the greatest program use (see Results) and aligned with our study focus. We sent an introductory email with a brief explanation of the study, an IRB-approved informed consent document (IRB #24-14: Vessel-based education and an analysis of the Science on Seneca Program), and time slots available for interviews. Participants that agreed to the individual interviews consisted of female-identifying teachers from five different public high schools (four rural, one suburban). The individual interviews were conducted via Zoom utilizing a semi-structured interview format (13 scripted questions total; Appendix B). Teachers were encouraged to elaborate on each response, as appropriate. Each individual interview lasted approximately 30 minutes.

The group interview consisted of seven individuals who had participated in the SOS teacher training in mid-April 2024. Three were teachers from schools in the region (two female-identifying, one male-identifying), while the remaining four were interested community members in related fields (three male-identifying, one female-identifying). After receiving the group’s consent to lead them in a recorded discussion, we asked the group three guiding questions (Appendix B). This interview lasted approximately 45 minutes.

Coding and thematic analysis of teacher interviews

Questions asked in the individual interviews and group interview were a combination of general and specific inquiries regarding the VBE experience and classroom applications (Appendix B). A thematic analysis was conducted of all individual and group interviews. First, we digitized transcripts, which were generated from the audio recordings of the interviews. Next, we emulated the methods of Braun and Clarke (2006) to code the transcribed responses to all survey questions as follows: (1) We familiarized ourselves with the content of interview transcriptions (i.e., the data for analysis), (2) We generated our initial codes by identifying interesting features of the data that were relevant to the purpose of the study, (3) From the initial codes, we organized them into themes that demonstrate a pattern among related codes, (4) We reviewed the themes to confirm that they connected back to the initial codes and the data set as a whole, revising and redefining them until all themes were appropriately named and representative of the data, and (5) We reported our final themes, using particularly salient and compelling quotations from the individual and group interview transcripts to support our major ideas.

Results

Survey of Freshwater Vessel-Based Education (VBE)

All 23 vessels surveyed operated VBE programs, but the vessels’ primary use and focal subjects during VBE programing varied. Out of the 19 programs (some programs have multiple vessels), K-12 day programming was identified as a primary use for the majority (n = 15), often in combination with other uses (Table 1). Only five programs exclusively focused on K-12 education. The Sam Patch and Riverie (Erie Canal and Genesee River, NY) were the only vessels that primarily served tourists interested in the river’s historical significance. A majority of freshwater VBE programs taught the biological, environmental, and aquatic sciences aboard their vessels (n = 16). VBE programs also taught history (n = 10), geography (n = 6), and navigation and other maritime practices (n = 6).

Table 1

Vessel-based education operating in the Laurentian Great Lakes and Northeastern USA. “Primary Use” includes education (E), research (R), community outreach (C), and tourism (T). “Target Audience” includes elementary (E), middle school (M), high school (H), undergraduates (U), teachers (T), and other (O). “Source of Funding” includes in-kind (I), private foundation (P), state grant (S), federal grant (F), and other (O). State University of New York is abbreviated as SUNY.

| VESSEL AND PROGRAM | PRIMARY USE | TARGET AUDIENCE | SOURCE OF FUNDING | AFFILIATION | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | R | C | T | E | M | H | U | T | O | I | P | S | F | O | ||

| Laurentian Great Lakes | ||||||||||||||||

| S/V Alliance, S/V Inland Seas Inland Seas SchoolshipProgram | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Inland Seas Education Association | ||||

| Amicus II Sea Change Expeditions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Sea Change Expeditions | ||||||||

| M/V Biolab, R/V Gibraltar III Stone Laboratory Field Trip Program | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Ohio State University | ||||

| R/V Blue Heron Large Lakes Observatory | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | University of Minnesota Duluth | |||||

| R/V D.J. Angus, R/V W.G. Jackson Water Resources Outreach Program | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Grand Valley State University | |||||||

| The Environaut Project NePTWNE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Gannon University | |||||||

| R/V Lake Guardian Shipboard Science Educator Workshop | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Great Lakes Sea Grant Programs (and affiliated universities) | ||||||||||||

| R/V Neeskay School of Freshwater Sciences | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | University of Wisconsin-Madison | |||||||||

| Sadie Ann The Sadie Ann Floating Classroom | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | University of Wisconsin Superior | |||||

| Northeastern USA | ||||||||||||||||

| Carillon Carillon Boat Tour Field Trip Program | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Fort Ticonderoga | ||||||

| R/V Goodwin Navigator Connecticut River Academy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Goodwin University | ||||||||||||

| R/V Gruendling, R/V Linnaeus Lake Champlain Research Institute | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SUNY Plattsburgh | |||||||||||

| R/V Marcelle Melosira Watershed Alliance K-12 Programs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | University of Vermont, SUNY Plattsburgh | ||||

| Riverie Environmental Education on the Genesee | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Corn Hill Waterfront and Navigation Foundation | ||||||||||

| Rosalia Anna Ashby LGA’s Floating Classroom | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Lake George Association (LGA) | ||||||

| Sam PatchEnvironmental Education on the Erie Canal | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Corn Hill Waterfront and Navigation Foundation | ||||||||||

| R/V Sloop ClearwaterHudson River Sloop Clearwater Sailing Classroom | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Hudson River Sloop Clearwater Inc. | ||||||||||||

| M/V TealThe Floating Classroom | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Discover Cayuga Lake | ||||||

| R/V William ScandlingScience on Seneca | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Hobart and William Smith Colleges | ||||||||||

| TOTAL | 15 | 9 | 8 | 2 | 10 | 11 | 14 | 12 | 13 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 7 | |

VBE programs typically attracted audiences from within their watershed (10–20 miles), but some participants travelled as far as 100 miles or from neighboring states. VBE programs most often targeted high school students (n = 14) or educators (n = 13). Undergraduate students (n = 12), middle school students (n = 11), and elementary school students (n = 10) were also important audiences for these programs (Table 1). Individual VBE programs served between 80 and 5,000 K-12 students per year. Seven programs indicated that they also serve the general public (i.e., local and public organizations, families, and lifelong learners), with individual VBE programs serving 10 to 7,000 non-students per year.

Many of the freshwater VBE programs were funded through private foundations (n = 8) and concurrently supported with in-kind sources (n = 8), state grants (n = 7), and federal grants (n = 6). Eleven out of the 19 programs were university affiliated. Seven vessels indicated that they were funded by only one source (Table 1).

Case Study of Science on Seneca

Demographic analysis

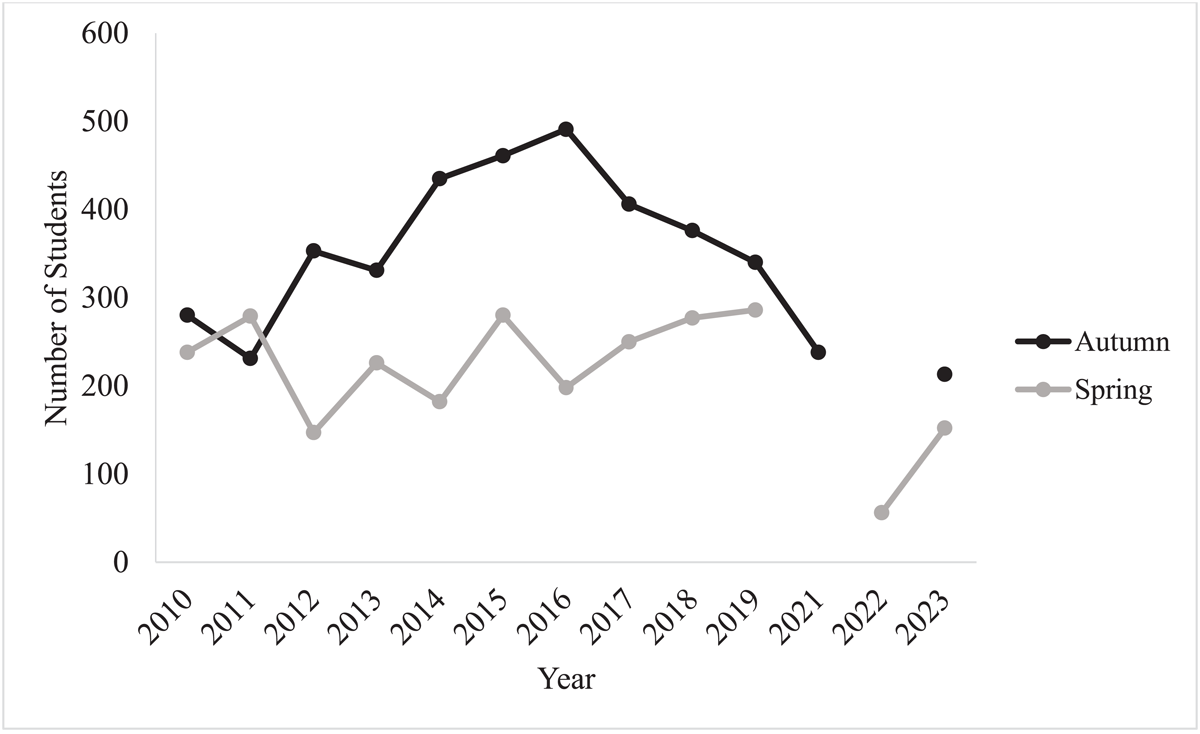

Science on Seneca (SOS) educated hundreds of area secondary students in Western NY per year. More students attended the program in autumn compared to spring (Figure 1). The average number of participants in autumn was 346 students (Standard deviation [SD] = 92.4) and in spring was 214 students (SD = 70.3). The maximum number of students in autumn was 491 in 2016, and in spring it was 286 students in 2019. During autumn, the total number of students generally increased from 2010–2016 and then decreased from 2016–2023. Spring use of the program was more variable.

Figure 1

Yearly participation in Science on Seneca’s vessel-based education program. The total number of students attending from 2010 to 2023 is separated by autumn (September through November) and spring (March through May). No cruises ran in 2020, spring 2021, and autumn 2022 (see Methods). The research vessel does not operate during winter conditions from late November through the middle of March.

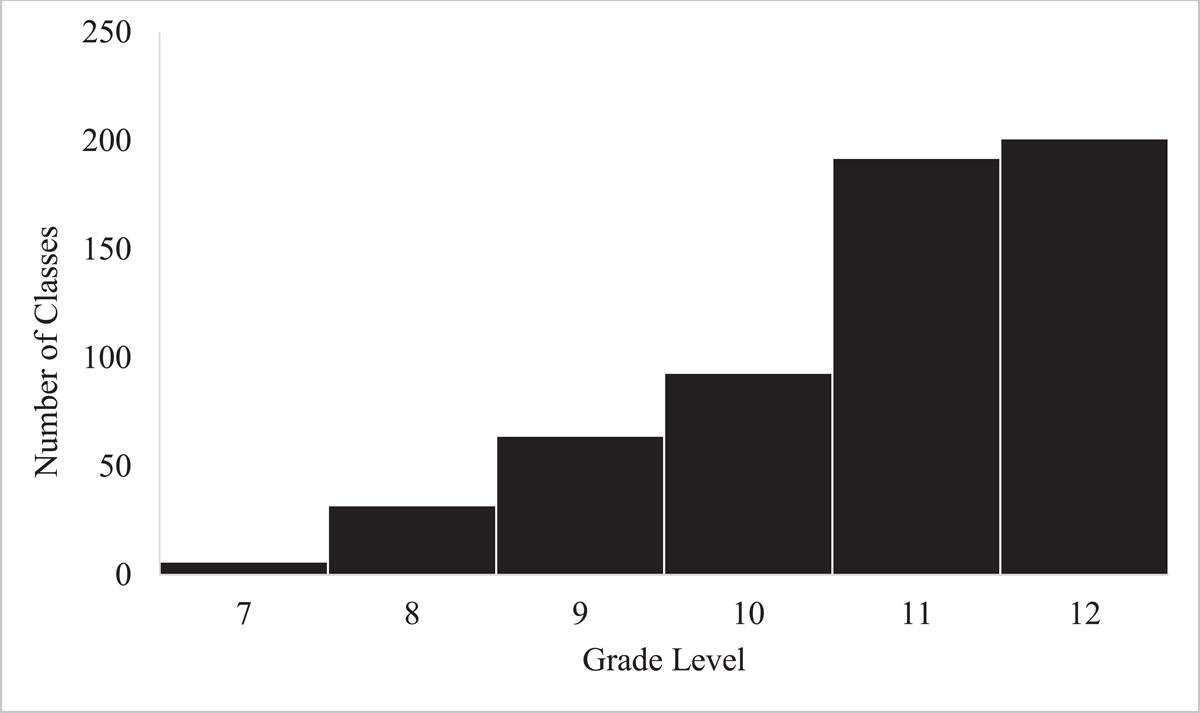

Students in higher grade levels used the program most frequently (Figure 2). Twelfth-grade (n = 201 total classes from 2010–2023) and eleventh-grade (n = 192 classes) were the most frequent participants. Grade levels between seventh and tenth ranged in frequency from 6 to 93 total classes. Seventh-grade classes had the lowest frequency (n = 6 classes).

Figure 2

Frequency of grade levels that participated in the Science on Seneca’s vessel-based education program. Bars sum number of classes per grade level from 2010–2023.

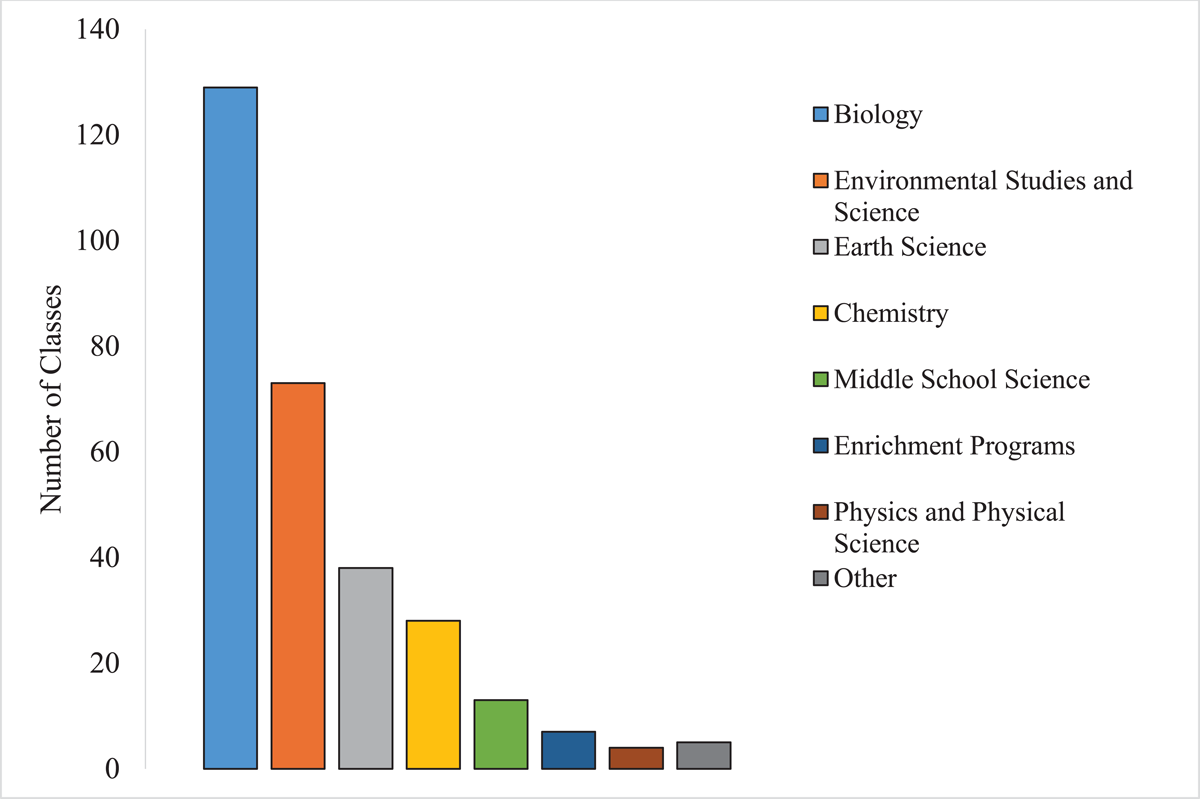

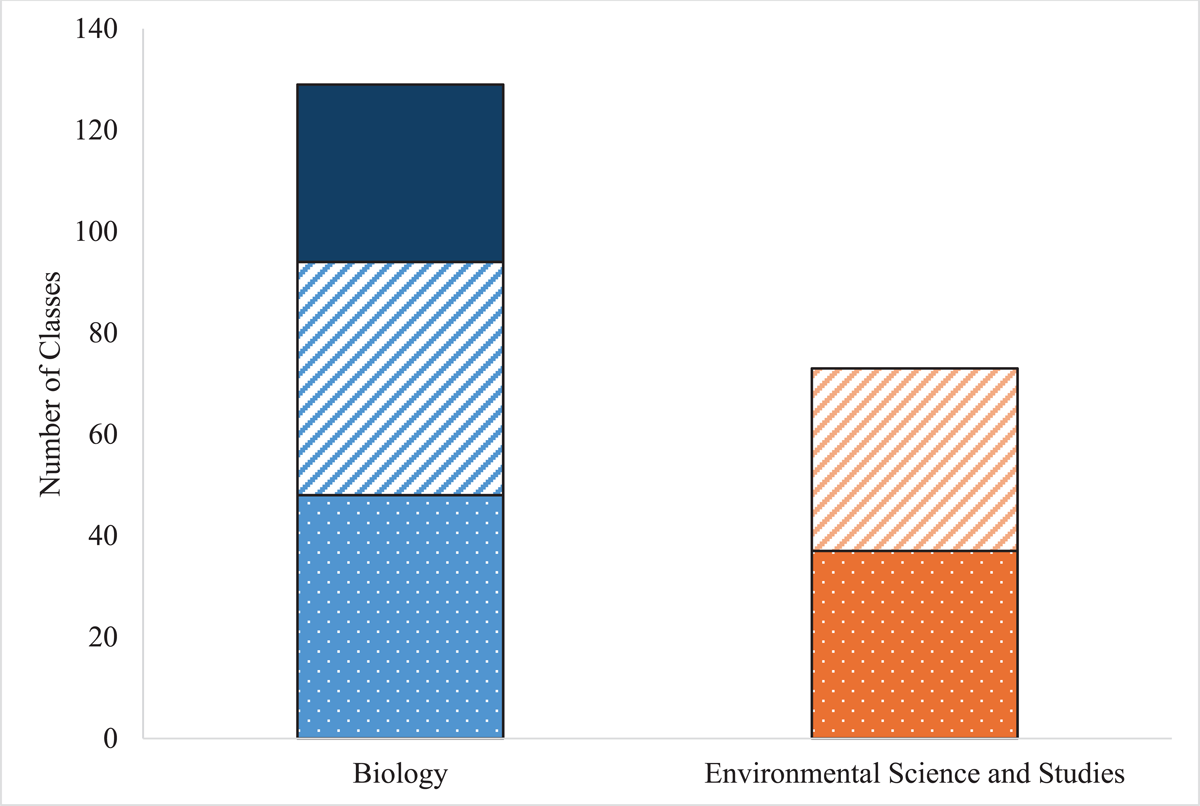

Biology classes participated at substantially higher frequencies (n = 129 total classes from 2010–2023) than all other subjects (Figure 3). General biology (n = 48 classes) and advanced biology classes (n = 46 classes) were the most common subject areas to attend (Figure 4). Environmental science and studies classes (n = 73 classes) also were frequent subject areas to participate in SOS, including advanced environmental science and studies (n = 36 classes) and general environmental science and studies (n = 37 classes; Figure 4). Physics and physical science classes (n = 4 classes) were the least frequent subject areas.

Figure 3

Frequency of class subject areas for Science on Seneca’s vessel-based education cruises. Bars sum number of classes per subject area from 2010–2023. Classes are grouped by broad categories. “Other” includes classes that were unable to be grouped into the other broader categories, including STEM, General Science, and 9th Grade Science. Breakdowns for Biology and Environmental Science and Studies are provided in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Frequency of class types within the broader “Biology” and “Environmental Science and Studies” subject areas for Science on Seneca’s vessel-based education cruises. Classes are separated among general (dotted), advanced (striped), and elective (solid) classes (see below examples by category). The bars sum number of classes from 2010–2023. General biology classes (n = 48) include Biology, Living Environment, and Regents Biology. Advanced classes (n = 46) include Advanced Placement Biology, International Baccalaureate Biology, College Biology, and Gemini Biology. Electives (n = 35) include various subdisciplines of biology. General environmental science and studies classes (n = 37) include Environmental Science, Environmental Education, Environmental Studies, and Environment and Society, whereas advanced classes (n = 36) include Advanced Placement Environmental Science, Global Environmental Science (Environmental Science and Forestry), Gemini Environmental Science, Advanced Environmental Science, Environmental Science (Finger Lakes Community College), International Baccalaureate Environmental Systems and Advanced Placement Environmental Education.

Schools that participated in the SOS program ranged from those located in Geneva, NY (the vessel’s homeport) to some over 60 miles away, including one in a neighboring state (Figure 5). The average distance of schools visiting the SOS program to Geneva, NY was 37.9 miles.

Figure 5

The proximity of schools participating in the Science on Seneca vessel-based education program to Geneva, NY, USA. Data includes any school participating in VBE programming from 2010–2023. Inset map shows geographic region of VBE and black star marks location of SOS. Size of red dots indicates total student enrollment (see key). Map generated in ArcGIS Online (2024).

Many schools participating in SOS were located in economically disadvantaged rural and urban districts, including two of NY’s largest cities: Syracuse and Rochester. Enrollment size of schools attending the SOS program ranged from 35 to 2,000 students. Thirteen schools exceeded an enrollment size of 1,000 students, and only three schools had less than 100 students.

Thematic Analysis of Teacher Responses

Four central themes were identified from our analysis of teacher interviews: (1) sense of aquatic stewardship, (2) interdisciplinary, experiential learning, (3) contribution to scientific research, and (4) on-board and logistical challenges.

Theme 1: Sense of aquatic stewardship

Teachers expressed that attending a VBE program encouraged students to examine the relationship between human actions and aquatic ecosystems, particularly anthropogenic impacts to local water bodies. One teacher in the group interview shared:

[Students are] becoming aware of whatever relationship there is between people and the land and the water and what’s in there, how it was formed, and also our impact, humans’ impact, on it over time…because they can see that there’s measurements for that. (Group interview)

Another interviewee shared this perspective, ‘…opening up your eyes to see like how does my behavior affect everyone else? How does that affect the environment that I live in?’ (Group interview). One teacher in an individual interview shared how students gain perspective about specific stresses to aquatic ecosystems:

I love this trip because it also shows human impact on the environment as far as understanding the implications of an invasive species…our kids know what invasives are, but to really see how that invasion has impacted the entire food web of the lake is huge. And then finally the whole piece about the salt mining and how inadvertent human action, you know—what was it?—60 years ago, is still having implications on an ecosystem today…so the human impact piece is huge for us too. (Individual interview 2)

Teachers emphasized how VBE allowed students to develop an appreciation for both the local watershed and a broader sense of stewardship and responsibility to the natural world. One teacher noted, ‘I spend a lot of time teaching them how to understand water quality and why it’s important for us to protect Seneca Lake—it’s our drinking water’ (Individual interview 1). Another stated, ‘I think the stories are really impactful…taking those pieces and putting them into action in their own lives as responsible citizens is really important’ (Individual interview 2).

In particular, SOS helped students develop an appreciation for the living elements of the ecosystem: ‘the thing they find coolest [is] the plankton tow [because] they can actually see…under the microscope. “What are the bugs in the lake?…Oh my gosh! That’s swimming”…Also the dredge…like, “what’s at the bottom of the lake?”’ (Individual interview 5). Another stated:

We live…15 minutes from the lake so for a lot of them [students] it’s a lake that they have driven around, swam in, boated on, and it [SOS] gives them an opportunity to see the lake, not just as a body of water but as an ecosystem. So being able to do a sediment dredge and see that there’s life at the bottom of the lake at different depths of the lake, being able to look under the scope and see this, all the zooplankton and the phytoplankton and all the things that are in the water that, to the naked eye, aren’t visible is huge. So definitely from an ecology perspective we use it for that. (Individual interview 2)

Theme 2: Interdisciplinary, experiential learning

Multiple teachers expressed the joy, reward, and efficiency of experiential learning that occurs during VBE. One teacher shared:

I can teach, what would take me probably a week in the classroom, by taking them on SOS, I can do it in like 3 hours…having a day where they [students] can actually experience it, touch it, feel it, see it, it’s so impactful but also like it’s just such a wonderful activity and it hits so many of our learning targets…(Individual interview 2)

Another teacher said, ‘I like the fact that it’s hands-on learning…I have a lot of students who take the class because they need one more science credit, and this is kind of an attractive thing to them, to do something that’s hands-on’ (Individual interview 1).

The value of interdisciplinary exposure to aquatic science and non-science through VBE was important to teachers. Teachers expressed that the hands-on learning provided by SOS accommodated students with varying background knowledge and academic interests, which allowed students to have ‘their own niche role’ during the cruise (Individual interview 4). One teacher noted, ‘I love that there’s the geological component, the biological component, and the chemistry component because my students have a variety of interests…exposing them to all of those disciplines I think is very valuable…’ (Individual interview 3). All teachers in the individual interviews valued their students rotating through the three activities that are covered during the teacher training for SOS: plankton collection and identification (biology), lake sediment sampling (geoscience), and water chemistry (chemistry). One teacher said, ‘I always have my kids rotate through everything just so they can experience all the different kinds of testing’ (Individual interview 2). Another teacher stated, ‘It’s not just biology. Like I really like anytime you can do a multidisciplinary approach… because we’re bringing in the water chemistry and earth science…I really appreciate that’ (Individual interview 5). One individual in the group interview particularly valued the connections to non-science topics made aboard the vessel: ‘Yes, a cross-curricular focus. Remember when we were looking how art could be tied in when they were looking at the different colors of the [sediment]?…I think that’s a great way of like doing it…making it more multidisciplinary’ (Group interview).

Theme 3: Contribution to scientific research

Teachers highlighted the importance of students contributing to data collection and engaging in ongoing scientific research. One teacher shared:

[I’m] a big believer in teaching students about citizen science and the fact that they collect the data and it becomes a part of a larger database—that we can look at over a period of time—allows students to see big picture, and the data isn’t just going on a sheet of paper and being tossed out when we’re done with the assignment. (Individual interview 1)

Another teacher shared, ‘they [students] know that it’s real science that’s taking place. It’s authentic…so they know it’s real and valuable’ (Individual interview 3). Another teacher said, ‘and it’s meaningful, right?…They are really contributing to long-term, really important research on and studies on the health of our drinking water’ (Individual interview 5).

Multiple teachers noted that the scientific research experience students gained aboard the research vessel could not be recreated in the classroom:

I think the opportunity to use the lake as a laboratory is something that really cannot be recreated in our traditional school limitations…dissolved chloride levels over time…we could recreate that in the classroom, the macroinvertebrate sampling we can create that in the classroom, but there’s a lot of other things that happen on the boat that just simply can’t happen in a building. (Individual interview 4)

Theme 4: On-board and logistical challenges

The primary concerns voiced by teachers were tangential to VBE and related to the logistics of getting their students to and from the program. Teachers explained that bussing—particularly driver shortages—and the constraint of the school day were challenges. Some teachers mentioned that the SOS program helps to mitigate these, ‘Bussing. Getting them there. But we’re really fortunate that they [SOS] are flexible with us…We have to wait for our elementary kids to get dropped off before we can get a bus driver…to take us’ (Individual interview 2). Another teacher shared:

Bussing and time. So unfortunately…they don’t have enough bus drivers so we really can’t leave the school until 8:45 and…it takes us an hour to get down to you guys and so it really limits our time there. We’ve had to cut it short…one time we had to skip our [post-cruise] lecture…I really found that part valuable because everybody gets to see all the different research that’s going on. (Individual interview 3)

Certain teachers responded, however, that the coordination headaches did not diminish students’ excitement towards the program. For example, one teacher stated:

I know that when I have a particularly large class you have to go into groups…and that has been a challenge for those kids that have to get back to school for sports and work and whatnot— but they’re just logistical things. I definitely don’t feel as though it’s challenging to get the students excited about it. (Individual interview 4)

Teachers also noted some student hesitation to be aboard a research vessel doing science independently. Some teachers expressed specific content was challenging for students, such as the chemistry methods, stating, ‘I didn’t realize how much time students need to do titrations before they go there, so that was something that’s really helpful to know in advance’ (Individual interview 3). Another teacher explained how they address general nervousness in advance of the VBE program:

They’re afraid of being on a boat, so, I think maybe there has to be a way…for some kids just to see the lake, and see that it is beautiful…A lot of kids just, they don’t go on the water and they’re just terrified so, but once they’re on it and they’ve had all those experiences, they change their mind. (Individual interview 1)

Additionally, teachers expressed a need for SOS to enhance the environmental topics and issues they touch on post-cruise. Suggestions made by teachers included creating an activity for students to conduct a data analysis, developing a citizen science project for students, leading an investigation of sources for nutrient pollution, engaging in comparative studies, and creating a pre-visit slideshow containing relevant background information. One teacher stated:

Maybe create an activity where students actually tap into the database and ask…questions and have that data answer those questions…You work with a class to develop some kind of project that they can work on, that would allow them to make a difference at the lake. Whether it’s cleanup or educating the public so that there’s less runoff, monitoring runoff at certain creeks…citizen projects that are real. (Individual interview 1)

Further, one teacher stated in the individual interview that a challenge was ensuring sufficient supervision for students as they rotate among activities:

It’s a little taxing for me to make sure that I have two other adults who are trained, who are available to go…I guess that would be the hardest part because we have to rotate the stations [activities], which is fine, just having someone be able to supervise those stations. (Individual interview 5)

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to collectively characterize VBE programs operating in freshwaters of the Northeastern USA and Laurentian Great Lakes. Residents of this region of North America, including those in major human population centers, occupy islands of land in a series of watersheds from the upper Great Lakes to the Hudson River’s drainage into the Atlantic Ocean. Previous case studies of floating classrooms have detailed the features and participant perceptions of several individual programs (Hunnell et al. 2023; Rowland & Kitchen-Meyer 2018; Twiss et al. 2005). We believe our higher-order survey of VBE programs is the first attempt in the literature to summarize the collective offerings of nearly 20 programs from the Great Lakes to the Northeast. Further, our analysis of 13 years of Science on Seneca (SOS), a VBE program operating for decades in the Finger Lakes of NY State, provides critical demographic and longitudinal insights on VBE as environmental education. Below we combined the implications of our approaches to reflect on (1) the audience and content of freshwater VBE, (2) opportunities for expanding aquatic education with VBE, and (3) additional logistics and challenges of VBE. Due to the broad nature of VBE, we encourage future study of VBE, which will likely provide additional perspectives and nuances that are absent from our analyses, which focused on the Northeastern USA, with particular attention to one VBE program and the reflections of a portion of its users.

The Audience and Content of VBE

The educational audience and geographic reach of freshwater VBE programs are impressively large. Individual VBE programs educate hundreds to thousands of participants annually. Several programs have been educating students for decades such as the Inland Seas Schoolship Program (Lake Michigan, MI), which serves as many as 5,000 students in a year, and SOS (Seneca Lake, NY), which educates hundreds of students annually and more than 7,000 students since 2010. Freshwater VBE programs operate in both urban and rural areas, mostly as partial-day field trips. Such accessibility is noteworthy as environmental education, in general, is spatially uneven with more programming in dense-population centers that are liberal-leaning (Hemby et al. 2024). Further, the SOS program demonstrates that VBE, while serving multiple high-needs communities (e.g., poorly resourced rural districts) in a local watershed can also encourage connection to globally significant environmental issues, such as nutrient pollution and invasive species.

The science of lakes and rivers is the focus of most freshwater VBE programs, and teachers use these experiences to meet science education standards based on our interviews with SOS teachers. Although some VBE programs cater to elementary learners, with simple hands-on activities and observation-based investigations, most aim programming towards middle and high school students for more in-depth limnological research. The student experience is often divided among data collection for the biological, physical, and chemical aspects of the water body, as illustrated by the programs aboard the R/V Blue Heron (Lake Superior, MN), Riverie (Genesee River, NY), and R/V William Scandling (Seneca Lake, NY). Similarly, on the R/V Lake Guardian participants gain knowledge about the biological, environmental, and aquatic sciences as the program aims to teach students and teachers about the Great Lakes (Twiss et al. 2005). To our knowledge, formal research concerning the outcomes of data-driven inquiry used by VBE is lacking for K-12 students, but studies document that undergraduate students appreciate and benefit from the use of such practices to teach freshwater science (Carey et al. 2015). Further, SOS teachers commented on the importance and power of such data collection. As data literacy is essential for aquatic and marine literacy, VBE programs will need to better develop the practice of organizing and interpreting ever more complex and plentiful data. Best practices are emerging for both shipboard experiences and classroom access to real-time and archived data (Miller & Nolan 2023).

Beyond the disciplinary sciences, our teacher interviews report the outdoor experience is a vital component of VBE with a lasting influence on participants that encourages healthy connections to vital aquatic resources. When students and teachers interface with aquatic ecosystems in meaningful ways, environmental awareness and appreciation for aquatic and marine systems increases, as does the development of social skills and self-discovery (Hunnell et al. 2023; Rowland & Kitchen-Meyer 2018; Wigglesworth & Heintzman 2017; Williamson & Dann 1999). Long-term shipboard programs, such as semester-long undergraduate courses in marine systems, are characterized as “powerful learning experiences”, which impact students’ thoughts and actions over time in a wide range of contexts (Rowland & Kitchen-Meyer 2018). Based on our thematic analysis of SOS participation, environmental awareness is a valuable outcome of freshwater VBE, but more research is needed on K-12 students given the wide-range yet short-duration of programing, as well as the influence of other experiences and demographics (Williamson & Dann 1999).

Opportunities for Expanding Aquatic Education with VBE

Although subject areas such as history, geography, and maritime practices are less common in VBE based on our survey and the literature about VBE, social dimensions are essential for connecting people to aquatic systems. Experiential learning, such as VBE, is understood to be an effective approach to increasing environmental stewardship because of the socio-scientific learning that occurs on board, which can encourage shifts in behaviors at the induvial and social levels (Morgan & Braungardt 2025). From our teacher interviews, we document that educators do extend to subject areas beyond the sciences to have greater reach and effect with their students. There are clearly opportunities for freshwater VBE to embrace the non-science aspects of water resources and environmental education. Such exploration will also create opportunities for participants inclined to the arts and humanities, those interested in environmental history and current policy, and students with aspirations to attain nautical jobs (e.g., engineering, cartography, navigation, engine repair). As aquatic educators, we also suggest that VBE programs would benefit from the explicit development of a watershed connection that better situates students in the waterscape and landscape by using GIS technology and/or other off-land experiences at the interface between land and water.

VBE programs may be interested in further developing environmental science and studies curriculum, including pre- or post-cruise lectures or lesson plans that accommodate environmental interests with greater intention. Despite the academic foundation (and current curriculum) of SOS in the disciplinary sciences of chemistry and geoscience, it is most often part of life science and environmental studies classes, a shared foci of many other VBE programs. To that end, we created a post-cruise activity based on teacher feedback for SOS that intertwines lake trophic status, nutrient pollution, and cultural eutrophication (Finger Lakes Institute 2025). These are prominent, interdisciplinary issues impacting lakes across the globe, including the Finger Lakes Region which was identified as a hotspot for harmful algal blooms (HABs; Wang et al. 2024). To comprehend and address the dangers of HABs, the intersection of multiple perspectives is necessary, including environmental legislation, the history of nutrient pollution, public health and economic impacts, and the role of global climate change (Egan 2023; Mclachlan et al. 2019).

Logistics and Challenges of VBE

Freshwater VBE programs are enabled by private and governmental funding, which highlights that they are viewed by these philanthropic audiences as consequential at the local and federal levels. It also suggests that freshwater VBE, as a whole, requires external funding to carry out at-sea education. Although most of the freshwater vessels we surveyed are not part of the Academic Research Fleet that is coordinated by the University-Oceanographic Laboratory System, there is a long-standing relationship between several universities and colleges that play a central role in the success of the VBE programs we surveyed. This is illustrated with SOS, which receives substantial in-kind support from Hobart and William Smith Colleges, including free training workshops, access to faculty and staff volunteers, and the use of a Coast Guard-certified vessel and its professional crew for a nominal fee ($25 per cruise; less than 5% of the cost to run the vessel for the cruise period) that is primarily used for undergraduate education and limnological research.

Even with substantial financial support, VBE programs face challenges. Teachers interviewed in our study shared that the most prominent barrier to student participation is a shortage of bus drivers, which, in part, reflects insufficient resources and funding for the travel needed to participate in education programs. These shortfalls may necessitate grant writing to support not only VBE programming but alleviate potential barriers associated with attending (e.g., Hemby et al. 2024). Declines in VBE participation, such as those that may be apparent in SOS since 2015, may result from teacher turnover, COVID-19 precautions, and transportation limitations. Additionally, teachers expressed the challenge of ensuring sufficient supervision while on board. The classroom teacher, despite the support from the sponsoring VBE, is integral in shaping the on-board experience for students, and future efforts for university-affiliated programs might seek to provide college-student volunteers to assist teachers with these endeavors.

VBE programs largely operate on vessels that serve multiple audiences (i.e., education, research, tourism), which create trade-offs for resources, data quality, and access to expertise among programs. Some programs are run by practicing scientists, others by teachers who have been trained by researchers, and still others by volunteers. The primary use of the vessel can also influence VBE programming due to available equipment, access to pre- and post-cruise data and materials, and program framing. Nonetheless, multi-functionality presents opportunities for synergies. For example, data collected by SOS students contributes to HWS-led research on Seneca Lake. We do note that more students attended SOS programming in the autumn compared to spring, likely because the academic calendar for upper grades poses conflicts (e.g., end-of-the-year regional and Advanced Placement exams) with the limited favorable conditions on northern lakes in the spring. Participating teachers and program coordinators should be cognizant that this artifact will influence citizen science as there are vastly different environmental conditions between autumn and spring on northern lakes (e.g., water temperature and patterns, biological activity; Anderson et al. 2024).

Another synergistic example of multiple-use vessels is the Riverie, which primarily operates, and generates revenue, as a tourist vessel on the Genesee River (Rochester, NY). It is also a crucial environmental education for the Rochester City School District as a universal fifth-grade field trip, during which elementary students engage in an investigation of the river that flows through their city; this may be transformative for students who are on the river (or even a boat) for the first time given there is limited accessibility to the river in this large urban school district (22,000 students, 90% economically disadvantaged; NYSED n.d.). This VBE operates from the income generated by the tourist-based vessel and engages a majority-minority school district (84% Black, African American, or Latino; NYSED n.d.) in otherwise inaccessible local “naturescapes” for disadvantaged students (Camasso & Jagannathan 2018).

Given that most aquatic, environmental issues can be experienced locally but are ultimately global in solution and interlinked with fundamental human rights (Hauschild et al. 2012), we highlight the need for VBE programs to connect with language classrooms and English Language Learners (ELL). While observing one VBE program we noted complications because the majority of students were ELL. Although some student materials were available in Spanish, even those were inaccessible to some participants due to their age and reading literacy, and instruction from volunteer staff on-board was exclusively in English. The expansion of existing VBE programs to develop resources for language learners is crucial to increase and sustain inclusivity and widespread impact.

Recommendations and Conclusions

Our collective study of programming in the Great Lakes and freshwaters of the Northeast shed light on specific, practical suggestions to improve VBE. First, we recommend that VBE programs address language and data literacy gaps (e.g., lessons in organizing and interpreting complex data, GIS technologies, support materials for ELL) to broaden the audience and effectiveness of VBE. VBE programs should also consider formally incorporating interdisciplinary watersheds education with explicit links to history, environmental policy, the arts, and nautical trades. These connections happen organically and haphazardly, and greater attention to non-scientific ways of knowing encourages lasting connections for participants. Second, we encourage the research community to study the elementary- and secondary-student experiences with VBE because of the dearth of known outcomes and diversity of approaches. Such work would complement the documented outcomes of the undergraduate experiences with VBE and potential actionable differences among education levels. Last, we suggest that supporters of VBE better encourage collaborations among VBE programs and develop solutions to known, addressable barriers (e.g., transportation to sites, on-board and post-cruise support).

Despite its tremendous potential, challenges are omnipresent as programs with similar goals serve varying audiences with unique needs. This underscores the necessity of ongoing flexibility and innovation within VBE to continuously adapt and accommodate participants. Future work on best practices, such as the age and time spectrum for programming, are needed, as is space for collaboration and conversation among VBE programs, including those in marine and freshwater ecosystems.

Although everyone lives in a watershed, it is often a privilege to access aquatic ecosystems and education about them. VBE programs can provide intellectual and emotional connections to the aquatic environment, which situate students in their watershed and broader community to feel pride and a humbling connection to their local water resources. Of course, a VBE program is not a stand-alone experience, but one in a series of environmental encounters that furthers learning and strengthens concepts and practices. For many teachers utilizing the SOS program, for instance, an important part of the experience is the reinforcement, post-cruise, of human influence on lake ecosystems and inspiring students to demonstrate environmental stewardship. VBE experiences are also a bridge to global water issues that interface with the climate and biodiversity crises, social justice concerning access to clean water, and ensuring safer interactions with water resources and recreation.

Appendices

Appendix A

Questions included in the freshwater VBE survey. Questions marked with double asterisks (**) were multiple-select (“checkbox”) questions that allowed “other” as an answer. All remaining questions were open-ended.

What is the name of your research vessel?

What is the primary use of your research vessel(s)?**

Do you operate an educational program aboard your vessel?

Who is the target audience of the educational program?**

How is the educational program funded?**

Is this educational program university-affiliated? (If yes, please state what university)

What topics are taught through this educational program?**

How many K-12 students (approx.) does the program serve in a year? (“Not known” is an acceptable response)

How many other individuals (community members/teachers/etc., approx.) does the program serve in a year? (“Not known” is an acceptable response)

What is the approximate geographic range of students/individuals attending your educational program? (“Not known” is an acceptable response)

Appendix B

Questions asked during the individual teacher interviews.

When you think about what you want students to get out of Science on Seneca from a curricular perspective, why do you participate in the program?

What are some of the other reasons you have your students participate?

What part of the Science on Seneca experience has been most helpful to you as a teacher?

What do you think your students get out of the program?

What parts of the program seem to resonate with your students the most?

What are some of the challenges you face in bringing students to do the program?

Which stations are you choosing to do when out on the boat with your students? As a reminder, there are three stations:

Water chemistry

Plankton and Lake Biology

Sediment

Do you do all three stations with your students?

How do you incorporate the experience on the boat and the data that you collected in your curriculum when back in your classroom?

Do you build on it in the next or future units?

A prominent issue impacting Seneca Lake is nutrient pollution. Excess nitrogen and phosphorus in lakes from agricultural runoff and other sources promotes the growth of harmful algal blooms. The algal blooms create issues for recreation, clean drinking water, and lake ecology, among other implications.

Do you teach aspects of this already?

(If yes) Can you tell me about what you teach and its role in your curriculum?

(If no) Do you think this topic might fit within your curriculum? What might that look like?

Part of my project is adding an environmental component to Science on Seneca, either contributing a piece of curriculum, developing a lesson plan, or writing additional pre-/post-lecture slides.

What additions to the program or resources would you find to be most useful?

Are there other things you might need to incorporate into your classroom (e.g., worksheets, slide deck that teachers, etc.)?

Is there anything you feel needs to change about Science on Seneca, so you are more easily able to translate the information learned on the boat back to the classroom?

Do you have any additional advice for me moving forward with this project?

Questions asked during the group teacher interview.

What do you anticipate being the biggest takeaways for students from their experience with Science on Seneca?

What environmental themes do you include (or could you include) in your classes that Science on Seneca currently interfaces with?

In your high school classes, do you focus on documenting environmental problems or finding solutions?

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Barb Halfman for archiving the Science on Seneca data, as well as the teachers who participated in the interviews and allowed observation during cruises. We would also like to acknowledge Drs. Ashley Eaton, Julia McKinster, and Matthew Crow for the conversation regarding the undergraduate Honors thesis that formed the basis of this research paper.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.