1. Introduction

This article argues that living labs, co-design and place-making deploy naturally overlapping action research methods that are embedded in place-based contexts, and which utilise social innovation through community co-creation to enhance local environments and spatial infrastructures and support social resilience in disaster and recovery contexts.

The concept of place-making originated as an urban planning approach in the 1960s (Jacobs 1961; Whyte 1980), and it has developed as a collaborative process by which people can shape their public realm, maximising shared value. It is recognised as an approach that supports the inclusion of diverse people to envision places together.

The Placemaking Clarence Valley (PCV) initiative was an action research project within Fire to Flourish, a pioneering five-year programme working in partnership with communities affected by the 2019–20 Australian bushfire season. Through a living lab infrastructure composed of a local community team and design researchers, this novel programme was formed to engage and support a group of regional localities to test place-based innovations in community-led disaster resilience.

The research question under investigation is as follows: How can the co-design of places help identify, describe, envision, and implement social and spatial infrastructures that strengthen social cohesion, social capital and resilience?

This article considers the key concepts and literature to define the approach, as well as critically reflects on its outcomes highlighting limitations and successes.

2. Conceptual background

2.1 Place-based approaches and social resilience

Place was only formally conceptualised as a meaningful part of geographical space by geographers in the 1970s (Creswell 2009). In theories of place, whilst location refers to the ‘where’ of place, ‘locale’ refers to the material setting for social relations (buildings, streets, parks), and ‘sense of place’ refers to feelings and emotional connection (Agnew 1987). In these ways, interpretations of place have highlighted it as more than a geographical location; it is socially created, culturally influenced, and a concept that blends both physical and human dimensions. The social construction of place acknowledges the way in which the world is inhabited and experienced. As Harvey (1993: 261) states:

Place is a social construct. The only interesting question that can be asked is, by what social process(es) is place constructed?

More recently, cultural geographers have argued that places are actively constituted, a product of coexistence and interrelations (Massey 2005). Rather than being homogeneous, place identities are produced as sites of shifting heterogeneity where people and place are in a state of constantly creating meaning.

‘Place’ is also an unequivocal aspect of people’s experiences of disaster. From phenomena such as topophilia marking people’s love of place (Barton 2017), and solastalgia capturing one’s sorrow at its destruction, processes that shine a light on rehabilitating places to build resilience and prepare for disasters are critical. Place in First Nations’ worldviews is as much about experience as it is about land itself, as encapsulated by the concept of ‘Country’ in Australia (Ganesharajah 2009). Sensory and environmental experiences of disaster connect First Nations’ wellbeing with connection to Country (Barlow 2022). A decolonised view of space is inherently linked to time (Smith 2012): a process, not only an outcome (Massey 2005).

In the same way that concepts of ‘place’ have developed in the academic literature, policy around ‘place’ has also evolved. Over the last decade, there has been growing commitment to place-based approaches from communities, governments, non-profits and research institutions in relation to resilience. Place-based approaches can be defined as:

collaborative, long-term approaches to build thriving communities delivered in a defined geographic location […] characterised by partnering and shared design, stewardship, and accountability for outcomes and impacts.

These approaches offer powerful ways to tackle major social and environmental challenges, including those connected to disaster recovery. Theories of regional development have advanced toward a greater understanding of the role of ‘place’ where:

globalisation has made localities and their interaction more important for economic growth and prosperity.

But place-based approaches bring with them a need for collaborative and participatory processes which can consolidate local values, generate trust, resolve conflict and mobilise resources. An increasing body of research has identified that the application of ‘one-size-fits-all’ approaches may be detrimental to sustainable development (Pike et al. 2006) and that ‘place matters’.

These concepts are important in relation to natural hazards and disaster preparedness contexts because they intersect with concepts of community resilience and social capital, and in particular the capabilities of communities to contribute. Contemporary societies depend on social cohesion for social resilience and those communities that have greater social and civic connectivity respond better to catastrophic events (Manzini & Thorpe 2018). In relation to disaster, the term ‘community resilience’ refers to the way in which communities come together to survive the immediate and ongoing effects of catastrophic events (Fischer 2008). Therefore, it refers to the collective ability of a place to deal with periodic and ongoing stressors and ‘efficiently resume the rhythms of daily life through cooperation following shocks’ (Aldrich & Meyer 2014: 255). The adoption of the term in disaster research acknowledges a shift in understanding about the interactions between natural and human systems in disaster events, particularly the role of human agency in both preparing for and mitigating natural disasters (Cutter et al. 2008). If resilience is the ability of a social system to respond and recover, it also includes its ongoing ability to make adaptations that reorganise and mitigate future events. Adaptive capacity is defined as the ability of a system to adjust to change and moderate the effects (Burton et al. 2002). The term ‘process-based resilience’ is defined in terms of continual learning and ‘taking responsibility for making better decisions to improve the capacity to handle hazard’ (Cutter et al. 2008: 600). Importantly, the concept of ‘Indigenous resilience’ points to the ways First Nations people have conquered racism and oppression alongside environmental shocks, disasters and the need to adapt within colonised contexts (Usher et al. 2021), highlighting that levels of human agency can be inequitable.

Critical to resilience is social capital. Social capital refers to the way in which involvement and participation in groups can have positive consequences for both the individual and the community (Portes 1998). Amongst three types of social capital, ‘bridging capital’ refers to acquaintances or individuals loosely connected across social groups, and often involves organisations such as civic institutions, schools, clubs and societies that are geographically linked. This type of capital has been shown to provide benefits in disasters including information and access to resources that assist in long-term recovery (Hawkins & Maurer 2010). Social resilience requires the existence of groups of people who interact and collaborate in a physical context. Proximity and relationship with ‘place’ are what enable these people to self-organise and solve problems in crisis or disaster (Sampson 2012).

Disaster researchers have examined these principles of social cohesion, social capital and resilience to provide policy interventions for government agencies. This is because it is well-acknowledged that the first responders and long-term recovery actors in disaster events are most often from informal networks of neighbours within a locality (Jennings 2019). Social infrastructure, networks and assets as well as partnerships between civil society, emergency agencies and government are all key to the effectiveness of resilience including:

focus groups, social events, and the redesign of physical and architectural structures to maximise social interactions.

These can be seen to deepen trust, strengthen networks, and improve social capacity and cohesion which may be of critical importance for neighbourhood resilience in future.

2.2 Living labs as infrastructure for place-based social innovation

The intersection between these concepts of ‘place’ with place-based approaches for disaster preparedness and resilience points to the need for new forms of place-based local infrastructure which can mobilise resources and partnerships for real-world experimentation, and trial new participatory and deliberative planning processes. Into this field, and with specific applications relevant to disaster resilience and climate transitions, living labs have emerged as socio-technical solutions addressing social and ecological challenges.

As a ‘relational infrastructure for transformative impact’, living labs bridge research and implementation, knowledge and action (Rye et al. 2025). Envisioned as locally grounded spaces for collaborative experimentation, they are aimed at producing evidence, innovative solutions and social learning to tackle global challenges related to sustainable development (Evans et al. 2015; Trencher et al. 2014).

In recent years, university living labs have developed as a model for research and education that emphasises real-world impact, combining applied, interdisciplinary work centred on sustainability, with teaching and collaboration with societal stakeholders (Evans et al. 2015). University living labs often deploy action research as a collaborative method that investigates and addresses issues simultaneously. Action research focuses on specific situations and localised solutions (Stringer 2014) and is often described as a cycle of action or enquiry, which involves systematic reflection and real-time intervention. As such it is inherently aligned with living lab methodologies and techniques. The intention of action research is that research and action must be done ‘with’ people and not ‘on’ or ‘for’ people. Enquiry based on these principles make sense of the world through collective efforts to transform it, and so it is a methodology that arguably goes beyond research and becomes propositional:

Action research has been described as a program for change in a social situation, and this is an equally valid description of design.

University living labs move beyond more linear modes of engagement to enable real-world experimentation and learning in response to societal challenges such as sustainable development (Hadfield et al. 2025). Some scholars have framed this approach as the university’s fourth mission—‘co-creation for sustainability’—emerging in response to the limitations of the ‘third mission’, which primarily emphasises linear technology transfer (Trencher et al. 2014). As a model of social learning for transformative change, living labs inherently integrate concepts of social innovation, which harness collaboration, participation and co-creation as core concepts. They can be understood as collaborative platforms that bring together diverse stakeholders, whether by choice or by mandate, who share a common understanding of a problem, recognise their mutual interdependence and work collectively to determine the most effective strategies for addressing it (Molinari 2011). Yet despite participation and collaboration being core to these concepts, there is less literature on the methodologies and dynamics that underpin the model (Puerari et al. 2018), and the way in which these methodologies already overlap with, and integrate, practices of design, co-creation and place-making.

2.3 Co-design, co-creation and place-making

In recent decades, there has been an increasing focus on user-centred design and the role of the user in the design process. This initially emerged through the notion of ‘participatory’ design in the 1970s, which fundamentally orientated around sustainability imperatives in which ‘citizen participation in decision making could possibly provide a necessary reorientation’ (Cross 1972: 11). This positions design as a potential activator of change (Papanek & Fuller 1972).

Since then, design disciplines have evolved toward user-centred design including ‘interaction’ design and ‘service’ design. The term ‘co-design’ refers to the inclusion of people not trained in design working with designers across the design development process and co-design approaches acknowledge a shift from design of ‘products’ to design of ‘processes’ that serves people’s purposes. Co-design methods have been developed to equip users with tools that can enable their active participation in the design process through provision of guidance, scaffolds and prompts, with new ‘roles’ for the designer as an ‘enabler’ and a ‘facilitator’ (Sanders & Stappers 2008). There is a consequent shift within the traditional hierarchy of the design process to acknowledge that users have expertise to bring to the process, including social, cultural and ground-up experience (Dodd 2008; Sleeswijk Visser et al. 2005; Sanders & Stappers 2008). More inclusive approaches (de Sousa 2021; McKercher 2020; Vanstone 2023) mean communities are enabled to co-develop place-based projects, programmes or services. In this way, many co-design and co-creation frameworks and tools deconstruct researcher–researched (Datta 2018; Smith 2012) or client–consultant dichotomies that exclude diverse voices. They also encourage researchers or practitioners to engage in self-reflexivity and positionality, a key aspect of decolonising methods (Ali et al. 2021; Datta 2018; Holmes 2020; Smith 2012), which in turn have strong interrelationships with co-design and co-creation processes.

An ambition of co-design is therefore that it is more inclusive, supports the formation of expanded, enhanced and more durable social networks, and contributes to social cohesion. These approaches acknowledge that:

design is an act of deliberately moving from an existing situation to a preferred one

and that new design methods are able to:

advance public and social innovation and achieve solutions beyond the reach of conventional structures and methods.

Co-creation is often used interchangeably with co-design, although it is arguably a broader concept, which has been increasingly used in relation to sustainability and transition theory and in literature that considers living labs (Puerari et al. 2018). Whilst the definition of co-creation is ‘making something together’, its further definition is not consistent, although it has been co-opted across multiple domains (De Koning et al. 2016).

Place-making is a community-driven process of designing and managing public spaces to strengthen connection, wellbeing and belonging, and as a form of co-design it relies on the active involvement of residents, workers and visitors as equal partners in shaping a shared vision for spatial infrastructure. As a collaborative, adaptive and inclusive approach carried out in partnership with local communities, it can deepen the relationship between people and the spaces they inhabit (Project for Public Spaces 2007). At its core, it focuses on generating social value by co-designing the built environment in ways that reflect the needs, values and aspirations of the community (Kelkar & Spinelli 2016). The democratic aspects of place-making strongly relate to ‘collective agreement-making’ practices pervasive in First Nations societies (Behrendt 2011: 149). While place-making carries Western distinctions of public and private space (Memmott 2003), First Nations’ worldviews of collectivism around spaces and places highlight that the rationale for many place-making processes are ultimately decolonising in their objective as they involve deep levels of consensus-building.

Participatory place-making approaches have been used as part of stakeholder engagement for architecture and infrastructure projects for several decades (Till 2010), but these methodologies have been fortified in more recent times (IDEO 2015). Hamdi (2010) suggests that clients, community beneficiaries, professionals and consultants can all occupy this field. This disruption of professional hierarchies supports diverse forms of expertise and stands in contradiction to more conventional consultation in which extractive participation can be characterised as ‘tokenism’ (Arnstein 1969).

Both as a conceptual and a practical tool for engaging communities in place-based thinking, co-design and place-making have been argued to contribute to individual wellbeing and foster access to social capital by building skills and expanding social networks (Corcoran et al. 2017). Connected and central to both co-design and place-based approaches are notions of community engagement, now prominent on the agenda for government agencies (Calvo & De Rosa 2017) and a core ingredient to enhancing citizen engagement in decision-making.

3. Case study: Placemaking Clarence Valley (PCV)

It is clear from the literature on living labs (Hossain et al. 2019) that they have durable common principles, methodologies, and objectives that overlap with co-design, co-creation and place-making. These include an ecosystem of users, citizens and end-users, an open innovation process, a human-centric design approach, and innovation activities through connectivity and collaboration in users’ natural environments (Leminen et al. 2012).

Based on these principles, a ‘place-making’ living lab can be defined as a type of living lab that supports social innovation through envisioning and testing new social and spatial infrastructures together. The potential value is generated through both the socially engaged process of co-creation itself (collective action to identify shared understanding and common needs) and the innovative outcomes generated from that process. These can include designs and prototypes for spaces, services and systems that are inclusive, sustainable, implementable and build social cohesion.

As a university living lab, a ‘place-making’ living lab can also be seen as an example of knowledge exchange and innovation: a collaboration between the university, public agencies and government, working alongside civil society. The ‘triple helix’ of innovation provides underpinning theories around how universities engage. It conceptualises how the interaction between the university works with external stakeholders to drive innovation in society. Rather than innovation running in a linear path from invention (in the university) to production (in society), the triple helix theorises the process as an overlapping ecosystem that requires curation and management. More recent manifestations of these theories include the ‘quintuple helix’ of innovation adding the dimensions of community, civil society and environment into the mix (Galvão et al. 2019).

Fire to Flourish was a five-year community impact programme providing support to communities as the first and last responders to disasters. Led by Monash University and operating across New South Wales and Victoria, it was a ‘place-based’ and people-focused initiative that aimed to co-create innovative approaches in community-led disaster recovery and long-term resilience. Operating at the intersection of community development and innovation, the programme worked within communities to explore, analyse, co-design and co-create the foundations for a thriving future that disrupts cycles of entrenched disadvantage (Fire to Flourish 2024).

Community-led action was core to Fire to Flourish, and each partner community ran its own stream of work, employing a local team of community-level programme coordinators, to address capability, skills, and needs through the provision of collaborative tools and processes which were co-developed with researchers to develop locally based initiatives. These initiatives were catalysed via grants to develop community-led projects.

Clarence Valley was one of the four local government areas (LGAs) in Fire to Flourish and included the four disaster-affected settlements of Glenreagh, Nymboida, Woombah and Blicks situated across Bundjalung, Gumbaynggirr and Yaegl Country (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Location of the Placemaking Clarence Valley (PCV) living lab.

The need for a community-led place-based process to imagine new social and spatial infrastructures and physical improvements was established by the Clarence Valley community lead at an early stage and emerged from initial broad community-based ‘co-design’ processes facilitated by The Australian Centre for Social Innovation (TACSI) (2025). Working with local coordinators, PCV therefore proposed that its initial grant round would include targeted funding for ‘place-making’ initiatives across the four localities.

The PCV process was established by community leads and the researcher–authors as a framework to co-design these initiatives. Grounded in concepts of ‘place’, ‘place-based’ approaches and ‘place-making’, it harnessed the community-led approach and used it to explore social innovation as a mechanism to enhance local physical infrastructure for post-disaster-affected communities. Whilst it did not originally use the explicit terminology of ‘living lab’, the framework can be clearly situated within this lineage, operating as a relatively protected space within which innovation and experimentation takes place (Bulkeley 2023).

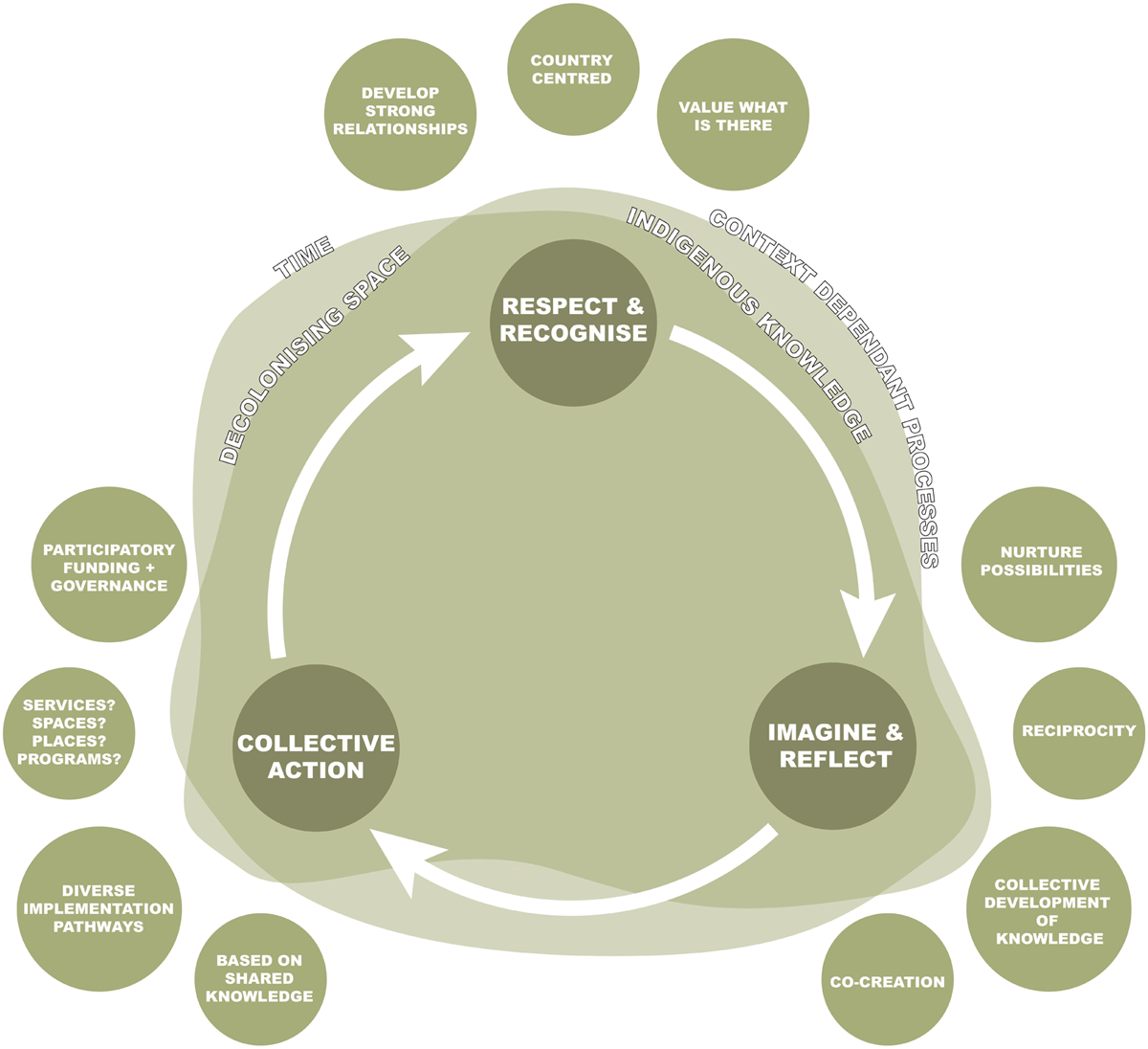

In developing a conceptual framework for the PCV process, a range of participatory design and co-creation approaches was drawn upon to create a bespoke process presented in Figure 2 and Table 1 (Muf Architecture 2009; TACSI 2025; Yunkaporta 2019). Underpinned by a relational and temporal way of working, the framework structures three stages of observation, ideation and testing which form an iterative process to develop place-based project concepts. The iterative framework acknowledges that co-developed project concepts, once funded, could subsequently go through another ‘loop’ of development using grant funds.

Figure 2

Placemaking Clarence Valley (PCV) living lab relational process loop.

Table 1

Placemaking Clarence Valley (PCV) methods of place-making.

| STAGE | APPROACH | TOOLS AND ACTIVITIES | OBJECTIVES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Respect and recognise | Informal engagement:

|

|

| Stage 2 | Imagine and reflect | Semi-structured exercises and workshops:

|

|

| Stage 3 | Collective action | Formalised teamwork:

|

|

The approach of the initial stage of the framework, ‘respect and recognise’ was to collaboratively explore deep physical, social and cultural contexts together, and build trust and relationships for inclusive and respectful participation in post-disaster communities. This created the groundwork for a second stage of collaborative ideation, entitled ‘imagine and reflect’, identifying issues and opportunities with local spaces and places, and co-creating concepts that could strengthen social cohesion and resilience. The third stage was ‘collective action’ in which agreement and prioritisation, as well as community capacity-building for implementation, were core activities and objectives.

The community team and the research team used the framework to develop the activities over the period of the living lab (see Table S1 in the supplemental data online), giving the opportunity for community teams to ‘own’ the activities, such that they could be used in transferable ways for future place-making.

The PCV living lab commenced in March 2023, spanning 13 months. Table S2 in supplemental data online outlines the place-making workshop design per locality, including the sequence of activities undertaken by participants to devise and prioritise project ideas (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3

Co-creation workshop within the Placemaking Clarence Valley (PCV) living lab (Blicks).

Figure 4

Co-creation workshop within the Placemaking Clarence Valley (PCV) living lab (Woombah).

Based across the four localities, place-making workshops co-created project concepts, which were developed through grant applications and granted projects. Whilst there is minimal space to describe the outcomes in detail, a range of projects for places and spaces emerged through the process.

In Tyringham (a part of Blicks), the place-making process culminated in the co-creation of a precinct plan that foregrounded community everyday needs and resilience. Currently the Tyringham precinct is home to a shop that sells petrol, general goods and alcohol. Community members worked within the living lab to reimagine the Tyringham precinct as ‘Totally Tyringham’, a strategic vision in which open space became a place for social gatherings and disaster preparedness, embedding adaptive capacity and readiness for future challenges.

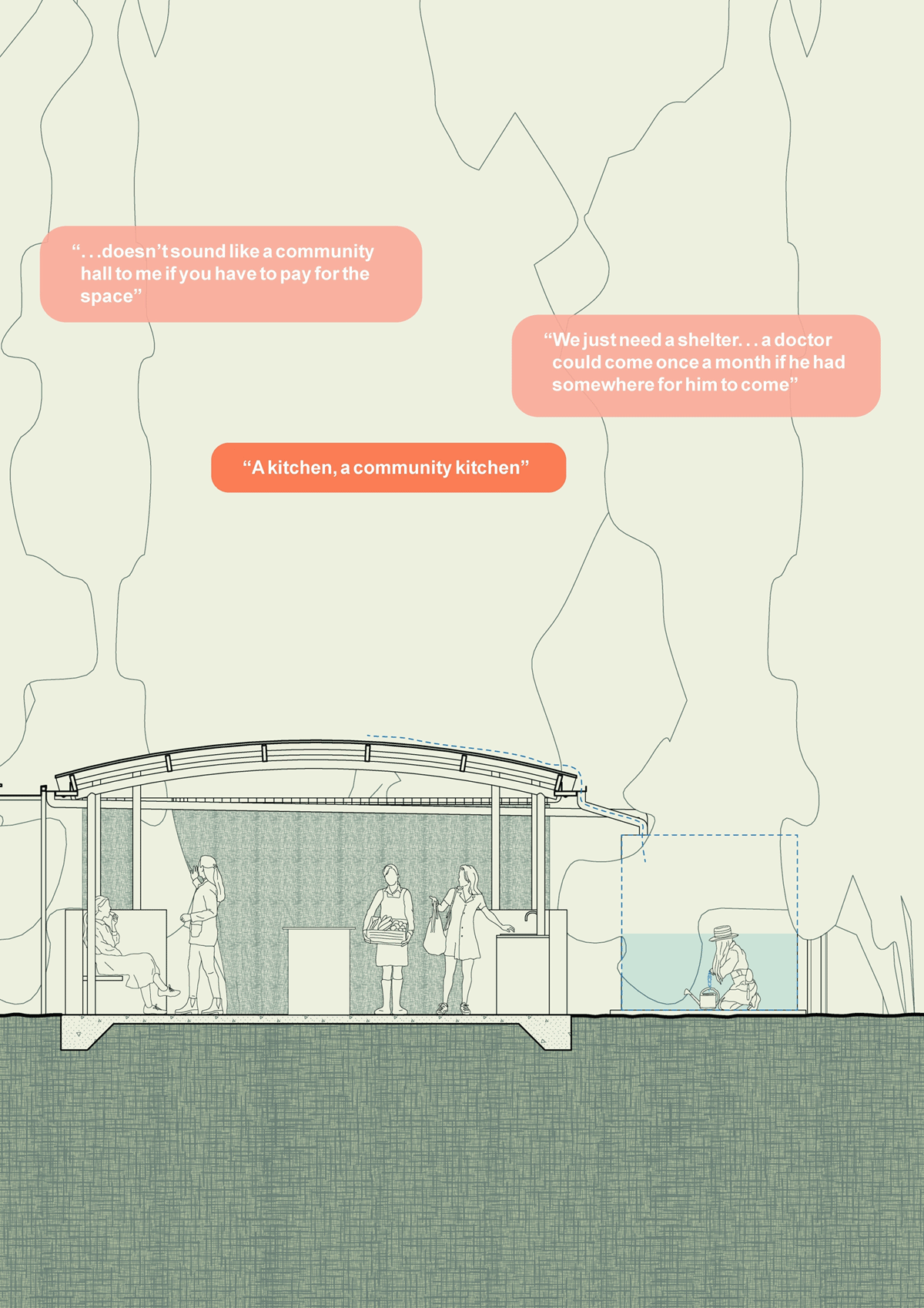

The Woombah shelter (Figure 5) emerged from community workshops that prioritised connection, open community accessibility, and resilience through both everyday use and in emergency settings. Located within a public reserve in Woombah, the shelter provides an undercover gathering space that supports both everyday use and disaster preparedness and responses, vital in rural communities where the in-person exchange of information underpins preparedness and collective security.

Figure 5

Woombah shelter section.

Drawing: Ashley Ho.

The culminating grant-making was a community-led decision-making process through anonymous preferential voting over a two-week period, carried out online and on paper. The projects commenced in May 2024, with an aim to be acquitted by the end of 2025.

4. Evidence and discussion

The research question for PCV asked the following: How can the co-design of places help identify, describe, envision, and implement social and spatial infrastructures that strengthen social cohesion, social capital and resilience?

The evaluation of PCV has sought to address its effectiveness in three ways:

in relation to its method and alignment to living labs

around the effectiveness in delivering co-designed spatial and infrastructural outcomes and

in the ability of the model to strengthen social cohesion and resilience for post-disaster communities.

Although co-design and co-creation are core methods for living labs, how co-creation works dynamically, and how ‘co-creation unfolds their impacts’ (Puerari et al. 2018: 1), are less studied. PCV aimed to be an infrastructure for mobilising and mediating post-disaster community-led co-design, specifically exploring this through considering ‘place’ and ‘place-making’ as core dimensions of co-creation in living lab contexts. The process, outcomes, evaluations and observations have highlighted that people, places, services, systems and the idea of ‘Country’ are interconnected in reciprocal overlapping relationships, and that disaster resilience can potentially be amplified when groups of people interact and collaborate effectively in a physical context. The physical aspects of ‘place’ cannot be extricated from this more complicated and dynamic set of social relationships and practices. This is partly because environmental and climate disasters are destructive of built and natural environments and heighten a focus on ‘place’. But it is also because physical ‘places’ are hubs for social connectivity and cohesion.

In this sense ‘places’ are both social infrastructure as well as spatial infrastructure. Spatial thinking and place-making explores people’s experience in spaces, dealing with the transformations, perceptions, actions and interactions that take place there. Services are complex relational entities, and their design focuses on the interaction between the service and the recipient, as well as the places and spaces where these services occur. These fields therefore overlap and form a dynamic and complex ecosystem in which social and spatial practices need to be considered simultaneously. These discoveries intersect with concepts of place established previously (Massey 2005) and which underpin social and spatial innovation.

PCV has shown that the structure and dynamics of design-driven methodologies such as co-creation and place-making can capture this complexity through both detailed design activities which foreground the contextualised knowledge and experiences of local communities in place, and the process of rehearsing and practicing participation, facilitation and organisational learnings collectively.

It is also of value to benchmark the PCV process in relation to other living labs given that there is a diversity of application contexts and a varied understanding and practice of the model. In recent frameworks that conceptualise co-creation in living labs (Puerari et al. 2018), common elements of co-creation have been extracted that can be mapped onto PCV. Primary to these is the ‘purpose’ of the co-creation which can be either related to ‘making together’ or to ‘learning together’. In the case of PCV the purpose is twofold: addressing concrete goals of co-creation (outputs, products, services, spaces and places) as well as the broader goals of ‘learning’ in which people collaborate, interact and form networks. The way in which place-making sustains these overlapping goals is a novel one, and testament to the interconnected relationality that characterises social relationships, social practices and social spaces.

There are, of course, challenges within the living lab model in relation to scaling of social innovation, and the present evaluation of PCV points to these issues. A common element of co-creation in living lab frameworks is in relation to formal and informal co-creation. Formal co-creation is defined by selected and defined ‘procedural steps, participants and audiences’ (Puerari et al. 2018: 5), whereas ‘informal co-creation’ emerges from working together and is characterised by broader but potentially less intense participation.

The grounded infrastructure of a living lab may implicitly be limited in scale, size, duration and impact. PCV, as part of Fire to Flourish, involved formal co-creation structured through the broader programme infrastructure, specifically on-ground and locally employed community leads responsible for initiating community-led place-making workshops and participatory granting with broader community members. This formality was an advantage in creating structured local audiences, but also potentially challenging in its capacity to co-opt wider informal audience ownership and ultimately gaining greater traction in the locality. This is challenging to evidence without more time, and more rigorous assessment, but is critical in terms of living labs’ objectives as vehicles for broader systemic change in relation to societal challenges such as sustainable development.

In relation to the second part of the research question—whether the living lab has been effective in identifying, describing, envisioning, and implementing new social and spatial infrastructures—the previous section has provided practical evidence of the outcomes, demonstrating how the process has given rise to a set of participatorily granted infrastructure projects to the value of over A$780,000. Whilst there are limitations here (the living lab’s 16 funded place-making projects are still in the process of ongoing development and implementation) the outcomes have clearly been identified, described and envisioned.

Establishing whether co-designed spaces, services and systems actually enhance social cohesion will require fuller evidence in due course. Reflective interviews with the community team at several points during the process has yielded other evidence regarding the success of the place-making process. Evaluation interviews were focused on the co-creation process, how it successfully delivered outcomes, what community connections and learnings had emerged, and how this has built community capability. The interviews are anecdotal in scale, so there are limitations to such findings. However, the interviews do illustrate generally positive feelings about the process, with several comments describing place-making as a successful form of community engagement. A community lead noted that:

In terms of community engagement, it has helped getting aligned with the local community’s own priorities—and previously we didn’t have the same level of engagement.

(Interviewee1)

Also, that the process:

tapped into something that people want, so it’s a real point of connection, to see change and for people to get involved, so it feels like quite an enabling kind of process.

These comments underpin the way in which the ‘place-making’ focus on socio-material infrastructure has created traction to build engagement, co-designing in ways that reflect the needs, values and aspirations of the affected community (Kelkar & Spinelli 2016).

The PCV process was also compared favourably with more conventional, transactional or tokenistic experiences of consultation:

When Council runs consultations there’s a panel on stage and everyone else on seats down below and we ask questions—question and answer. So yes, this was quite different and inclusive. It played to everyone’s individual ways of thinking—with the variety of activities they had for people to contribute their ideas—some people worked with the clay, and drawing and putting flags down on a map.

(Interviewee1)

In relation to individual tools and techniques, community leaders felt it was novel and unusual:

In a very short period, we were able to draw people into contributing and talking about their town or their region. People were surprised by the process—it was not what they were expecting, but in the end, they enjoyed it. It was totally different to what they’ve been through before.

(Interviewee1)

These comments speak directly to the dynamic, relational and playful activities that structured the workshops, and to how these forms of creative experimentation shift normative or siloed thinking about the built environment.

As a First Nations community lead highlighted:

the processes explored needs, connection points and access for services and culture. It highlighted those links and in doing so, broke down many barriers. People’s resistance dissipated and in turn created a series of ‘connection cogs’ that helped progress and incite action. The creative and visual practices encouraged even the biggest cynics to eventually ‘jump in the ring’. They wanted to highlight their knowledge, their connection to their places and share dreams about their Country, they wanted to be engaged! They could see this was about them and a better future for all, it was visual, it was physical, it was connected and heartfelt. It had a purpose!

(Interviewee2)

Despite initial concerns regarding the scope and level of co-design activities, community members enjoyed what emerged in terms of ideas:

Some of them grumbled it was childish […] but then they all came on board later. They could see that there was something coming out of it.

(Interviewee2)

Many participants emphasised a desire for accessible and inviting spaces to gather, celebrate, exercise, get to know their neighbours and ultimately be in a better position to look out for one another in times of emergency. In general, and as noted:

It did achieve, it almost superseded expected outcomes. The initial vision that came through has some really big ideas in there—which surprised me—really good.

(Interviewee3)

Conversely, some notes of caution also indicate limitations. The place-making process outcome was to submit and win grant funding; therefore arguably, the overall marker of success is dependent on the final implementation of built outcomes:

Nothing’s been delivered yet, so there’s always that: when are we going to see outcomes? So, we’ve connected into something good, but we also need to see carry through.

(Interviewee4)

Although participation was reasonable and increased over time, the numbers and diversity, and in relation to First Nations peoples, were still ultimately low, especially relative to the population of each locality. The relational aspects of place-making require time to develop, and deep levels of First Nations engagement could not be achieved within the timescale. Finally, whilst participant interviews have shed light on experiences, hybrid approaches will need to be used in future for the evaluation of social values, developed in collaboration with participants. This aligns with ‘citizen evaluation’, where non-researchers help assess research outcomes (Soler-Gallart & Flecha 2022). Depending on context, evaluation can be qualitative, quantitative or mixed-method, and could include tools such as self-reflection or peer-to-peer review built into the co-design process. Such flexible, context-specific methods could offer richer insights and preserve the project’s original meaning—often lost in traditional evaluations (Pearson et al. 2025).

In relation to the research question’s final part—whether PCV has strengthened social cohesion, social capital and resilience for post-disaster communities—additional analytics were gathered by the research teams from the broader community via the community survey and the preferential voting system which has provided some evidence around broader engagement and social value. Responses to place-making surveys developed and distributed by the local community team informed the process. Engagement with the community-led survey piqued interest in the research itself, with 127 people across each locality attending the workshops. A community exhibition of outcomes from the workshops coupled with feedback forms allowed participants not only to explore the findings some months later but also to engage with visualisations of design possibilities along with mechanisms to offer critique. The culminating participatory granting encountered over 400 votes across the four engaged localities, enabling community-led decision-making.

The Fire to Flourish programme also carried out an impact assessment for each LGA in 2023, which has provided reflections. The survey was distributed to 340 community members across the four partner localities in Clarence Valley in December 2023. The survey included 49 questions designed to elicit community perceptions of Fire to Flourish’s impact across six domains. For Clarence Valley the highest measure was around domains of resilience for social capital, scoring 6.09 (a positive impact, where 5.0–6.99 is a positive impact). This measure was the highest amongst the four LGAs defined as:

strengthened community leadership and social cohesion through community engagement, governance and capability building that brought diverse people together around a shared vision for disaster resilience and community flourishing.

The PCV living lab was a key component of Fire to Flourish’s activity in Clarence Valley LGA, including the largest granting round. Such results provide evidence for initial concepts in this article, that ‘place matters’ (Pike et al. 2006) and forms a critical part of the ‘bridging capital’ (Hawkins & Maurer 2010) that social cohesion is reliant upon in regional contexts.

5. Conclusions

The evaluation and learnings from Placemaking Clarence Valley (PCV) provide some evidence that the process has had local impact in relation to the interconnected objectives of the research questions. In relation to the broader concepts introduced above, lessons can be drawn from the PVC living lab experience for future living labs.

The PCV living lab model has shed light on the way that co-design and co-creation are core components in the methodology of the living lab model. In particular, they underpin the way in which living labs structure social innovation. The definition of social innovation is new ideas that are utilised to meet social goals (The Young Foundation 2007). By its very nature, place-making provides a powerful framework for social innovation in living labs, addressing social and environmental challenges in place-based contexts and having community, even societal impact. Social innovation can prototype new forms of collaboration in places through a design process. This is especially powerful through a decolonising lens. Design deals with continuously evolving and expanding contexts, with possible future worlds. It can be applied to solutions for the physical world as well as the socio-cultural world because it is multidisciplinary, committed to conceptualisation, configuration and implementation of meaningful social environments, spaces, services and systems. In this way, place-based forms of social innovation framed in living labs can utilise design thinking, especially through co-design and co-creation methodologies, to consider new possibilities for services and spaces. A place-based conceptualisation of transformation thinking can address the often-abstract translational problems of research and policy by testing social innovations in action. More broadly, place-based forms of social innovation that are framed in living labs may be able to create conditions for scaled-up ecological transformations if adapted and replicated across localities.

PCV is an example of a university living lab and provides insights into the particular values that this model offers for knowledge exchange, particularly in relation to ‘triple helix’ theories of innovation in which overlapping ecosystems across civil society, government, and the university require curation and management. As a place-based local infrastructure that consisted of both a community team and a research team from the university, PCV initiated meaningful action research and generated local data, engaging a broader demographic than might typically be possible, and working as both agents and intermediaries. Research is often a dirty word (Smith 2012) for many remote and regional communities in Australia, particularly First Nations peoples who have experienced extractive research for generations. Yet when derived from the ground up and governed in a self-determined way, PCV demonstrated that action-based research through a living lab infrastructure can be a powerful asset for local groups to lead their own initiatives. In addition, place-making and place-based initiatives often rely on diverse technical skills to augment the ways in which community-led insights can be realistically implemented and evaluated. Technical activities such as developing feasibility studies or concept designs present significant challenges for some communities to take the next steps (Cavaye 2001), even when funding is available. The PCV process experimented with how a living lab between a community and university can effectively bridge these gaps through knowledge- and skills-sharing.

These outcomes suggest place-making living labs in university contexts can provide research, service learning and technical support which help communities through multiple implementation cycles required for social and spatial infrastructure outcomes. While these methods were effective, the enduring issue of a finite timeline prevented higher levels of engagement by broader populations in each locality. Despite this, the time barrier was ‘hacked’ by the long-standing relationships the community leaders and their extended teams on the ground already had with local people.

These pre-existing, deep levels of trust enabled the novel PCV process to emerge powerfully in each context within a relatively short period of time. While the wicked problem of ‘enough’ time exists for any living lab model or project, what can be learnt is that maintaining durable, long-term relationships with communities is critical to the success of living labs and university partnerships are often well-placed to facilitate this.

Although there are clear limitations in relation to the robustness of the evaluations of PCV, particularly evidence on its social value, these findings are consistent with previous reviews on co-creation and co-design, which have similarly noted a general lack of empirical reporting on project results (Wang et al. 2022; Pearson et al. 2025). This gap may stem from the absence of robust evaluation frameworks within the field (Iniesto et al. 2022). Certainly, there is an inherent tension in assessing the social implications of relational place-making using dominant forms of evaluation, because relational design is ‘open-ended, mobile, networked, context-specific and actor-centred’ (Nielsen & Bjerck 2022: 1061).

Overall, the PCV case study has demonstrated that embedding creative place-making practices within experimental socio-technical infrastructures, such as living labs, offers a powerful path to co-designing new services and infrastructure. This approach fosters meaningful, ongoing conversations, creating a platform for shared knowledge and deep collaboration, and fundamentally shifts away from the dominant top-down paradigm of disaster preparedness, which relies on centralised authority (national or state governments) dictating a one-size-fits-all strategy for communities. Instead, it champions community-level disaster resilience that explicitly accepts and incorporates the place-based intricacies of remote and regional areas.

The key lies in place-making itself. As Bulkeley et al. (2016: 15) noted: ‘power is a distributed property’. This means the built environment (the socio-material world) as a mediating entity, shapes and is shaped by people. Place-making living labs disrupt this strict bottom-up and top-down binary. By providing participants with the tools and personal agency to navigate and intervene within local and neighbourhood spatial infrastructure, the lab creates a third space or collaborative loop where institutional tools and resources are brought down to the local level, and local knowledge and creative inputs are integrated into institutional planning. This hybridisation creates reproducible and adaptable approaches to building durable social resilience by making power relational rather than simply directional.

Acknowledgements

The Placemaking Clarence Valley (PCV) living lab was conceived on the unceded lands of the Bundjalung, Kulin, Gumbaynggirr and Yaegl peoples. The research team acknowledges the First Nations connection to creative practice and pays respects to Elders past, present and emerging. Special gratitude is paid to Elder Aunty Patricia Laurie, Yaegl Elder Aunty Diane Randall and Gumbaynggirr Elder Uncle Gary Brown for welcoming the researchers to Country and sharing stories and knowledge of their places at various points throughout this project. The research team also thank Roxanne Smith, Pamela Denise and Cara MacLeod for their creative leadership, collaboration and insights that have highly influenced various aspects of this research project.

Author contributions

The authors contributed to all aspects of this research paper alongside playing key roles within the living lab itself. M.D. conceptualised the Codesign for Placemaking research stream within Fire to Flourish and is the chief investigator of the project. N.M. is the research fellow and co-lead of this research team and led the research design and implementation of the Placemaking Clarence Valley (PCV) living lab. R.L. is the research assistant of this research team and co-taught the service-learning component of the programme.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Data accessibility

The datasets are available from the authors upon request. However, the research team is required to gain re-consent to share the data depending on what is required, in keeping with data sovereignty principles.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be found at: https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.634.s1