1. Introduction

In the context of urban development – particularly within experimental formats such as living labs – the question ‘Who is doing the work?’ (Lorde 1984: 30) foregrounds the complex interplay between individual and collective roles (hooks 1984). Building on practical experiences from two German living labs – Quartier:PLUS in Braunschweig and Österreichischer Platz in Stuttgart – this paper applies intersectional and postcolonial perspectives (hooks 1984; Lorde 1984; Roig 2022) to examine the power relations and role dynamics within participatory planning processes. Special attention is directed towards the challenges and potentials of ‘double or multiple roles’ and the associated necessity of ‘code-switching’ (McCluney et al. 2019).

Both living labs emerged from bottom-up initiatives in which individuals or groups identified specific local needs and initiated participatory projects that subsequently evolved into iterative spaces of experimentation, observation and empowerment. Although not originally conceived as living labs, these initiatives developed organically through informal learning and trial-and-error practices rather than formalised research designs. They bridged the gap between small-scale interventions and broader urban imaginaries, generating alternative approaches rooted in practice. Emerging independently of institutional actors, they created and served as interfaces between informal and formal structures while fostering new forms of cooperation among residents, civil society organisations, municipal administrations and public institutions. Within this context, the ability to assume double or multiple roles and to engage in code-switching emerged as an indispensable competence without which these projects could not have been sustained.

The analysis also situates these initiatives within the German urban development context, where colonial and racist structures – beyond the legacy of National Socialism – remain insufficiently scrutinised (Eckardt & Bouguerra 2021). Retrospective reflection through peer interviews, grounded in intersectional and postcolonial perspectives, highlights how the capacity to navigate multiple roles and to code-switch across social and institutional domains enables mediation between actors while also producing risks of overburdening, insufficient recognition and the reproduction of structural inequalities in living labs.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 outlines the theoretical framework, Section 3 describes the methods, Section 4 presents the two case studies, and Sections 5, 6 and 7 contain a critical reflection, discussion and interim conclusions.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1 Double and multi-roles

In the context of collaborative projects – transformative living labs initiated by collectives – moderation, translation and mediation emerge as key roles (Hernberg 2022). Individuals who navigate and mediate between social and professional contexts play a crucial part in bridging infrastructural and epistemic gaps, thereby contributing to the creation of more inclusive and equitable urban spaces (Baum et al. 2020). These intermediary actors (Hernberg 2022: 109) often assume double or even multiple roles, as they mediate between different knowledge systems, disciplines and interest groups (Blundell Jones et al. 2013). Double or multi-roles in living labs refer to positions in which individuals simultaneously embody multiple, often contradictory identities – such as architect-activist, practitioner-researcher or community member-expert. They act not only as professionals with specific expertise but also as bridge-builders between public administration, civil society, academia and the private sector (BBSR 2017; Hernberg 2022; Oswalt & Misselwitz 2004). Their dual role can, for instance, manifest in their simultaneous affiliation with an institutional structure and an activist movement. Multi-roles particularly emerge in complex urban transformation processes where hybrid forms of collaboration take shape (Defila & Di Giulio 2018: 223). One person may act simultaneously as an academic expert, a moderator of participatory processes and a practitioner in local projects (Gray & Malins 2004). While these roles may be theoretically distinct, in practice they are inextricably interwoven (Dodd 2019). Double and multi-roles allow for the integration of diverse perspectives but also entail challenges: they require a reflexive practice to identify one’s own positionality and potential conflicts of interest. They demand strategies for handling role conflicts and developing context-sensitive approaches (Hernberg 2022; Oswalt et al. 2014).

Multi-roles generate ambiguity owing to unclear expectations. This may result in uncertainty and overload but it also holds creative potential. At the same time, multi-roles open new spaces for action, as they enable actors to combine multiple logics and develop innovative solutions (Harriss et al. 2020). By moving within and across these roles, individuals not only influence decision-making processes but also transform how knowledge is produced, disseminated and applied (Hernberg 2022; Oswalt & Misselwitz 2004).

The combination of cognitive flexibility, situational knowledge (Haraway 1988) and strategic action thus becomes an essential resource for adaptive and (in)equitable negotiation in living labs. Double and multi-roles should therefore be recognised both as a source of power and innovation and as potential sites of conflict and marginalisation.

2.2 Code-switching as a linguistic and intersectional practice

Code-switching – the ability to consciously shift between behavioural practices in different contexts – emerges as a key competency in mediating roles. An individual’s personal standpoint and tacit knowledge are central factors in this process. Thus, examining these roles and the capacity for code-switching – navigating between them – is crucial for understanding collaborative projects such as living labs. Code-switching refers to the deliberate shift between different languages or forms of expression depending on the social context. This may include the alternation between entire languages as well as changes in vocabulary, tone or body language (Myers-Scotton 1993). While code-switching is often considered a natural linguistic practice in multilingual societies, it is particularly evident among marginalised groups, such as racial and ethnic minorities, LGBTQ+ individuals, people with disabilities, women, people on low incomes, Indigenous peoples, refugees and migrants, and people experiencing homelessness. This demonstrates that code-switching is not merely a linguistic phenomenon but is also deeply embedded in societal power structures. It serves as a tool for adaptation and social positioning, and as a protective mechanism against structural and institutional discrimination (Roig 2022: 79). From an intersectional perspective, bell hooks (1994) views the ability of code-switching as a survival strategy for marginalised groups, particularly Black women, who must navigate between dominant and subaltern spaces to signal belonging or to differentiate themselves from other groups. She illustrates how the ability to linguistically shift between these worlds can provide access to power structures, while also causing emotional exhaustion. In professional contexts, McCluney et al. (2019) analyse how Black employees often engage in code-switching in order to be perceived as professional. This pressure to adapt – manifested in language, behaviour and habitus – can result in long-term stress and identity conflicts, understood as inner tensions that arise when different aspects of a person’s self-concept or social belonging come into contradiction.

Kübra Gümüşay, in her book Sprache und Sein (2021), reflects on the power of language and how it shapes identity (Gümüşay 2021: 63). She discusses code-switching not only as a linguistic skill but also as a result of social inequality and adaptation, whereby people with a migration background or a non-dominant native language often adjust their way of speaking through language, word choice and dialect in order to be taken seriously (Gümüşay 2021: 157). It becomes evident that code-switching goes far beyond a purely linguistic practice: it reflects social inequalities and pressures to conform, while also potentially serving as a means of self-determination and resistance.

2.3 Intersectional perspectives

The intersectional perspective reveals structural oppression and is essential for identifying various forms of discrimination and creating spaces in which they can be negotiated (Roig 2022: 16). Intersectionality, a term introduced by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, describes how individuals are affected and disadvantaged by various forms of discrimination, particularly within the legal system (Crenshaw 1989). This concept has been taken up and developed further by many other actors, such as Patricia Hill Collins with her matrix of domination, which illustrates the interconnected nature of gender-based, class-based and ethnic-based oppression (Hill Collins 1990). For her:

Intersectionality refers to particular forms of intersecting oppressions, for example, intersections of race and gender, or of sexuality and nation. Intersectional paradigms remind us that oppression cannot be reduced to one fundamental type, and that oppressions work together in producing injustice.

Angela Davis builds on this perspective by emphasising the links between racism, capitalism and patriarchy. Davis’s work primarily focuses on the role of the prison system and how structural violence systematically disadvantages marginalised groups (Davis 1983). Another significant contribution to intersectional theory was made by Chandra Talpade Mohanty, who challenged Eurocentric feminist perspectives and promoted a postcolonial view of women in the global south (Mohanty 1984). Judith Butler, on the other hand, refers to gender in her work, further developing intersectionality theory with regard to gender and power structures (Butler 1990). In her book Living a Feminist Life (2017), Sara Ahmed discusses related issues and explores how feminist struggles are intertwined with other forms of oppression, such as racism.

bell hooks, as an author and lecturer, believed that education was the key to overcoming oppression (hooks 1994). She demonstrates how Black women and other marginalised groups are frequently compelled to navigate conflicting identities, acting as intermediaries between academic and activist spaces, for instance (hooks 1984; 1994). Although these multiple roles are born of necessity, they can also be a form of resistance, particularly in contexts of racism, sexism and classism.

Audre Lorde criticises white feminism, placing the intersectional consideration of identities at the centre of her political and literary work (Lorde 1984). She explains that multi-roles arise from the necessity to function within dominant power structures while simultaneously resisting them. A central concept in Lorde’s work is that such multi-roles are not merely burdens but can also be sources of resistance and insight:

One of the most basic Black survival skills is the ability to change, to metabolize experience, good or ill, into something that is useful, lasting, effective. Four hundred years of survival as an endangered species has taught most of us that if we intend to live, we had better become fast learners.

Emilia Roig explores how patriarchy is historically entangled with racism and capitalism and uses intersectional and postcolonial theories to address the challenges of multi-roles (Roig 2022: 15–16). She shows how people belonging to multiple marginalised groups are often caught between contradictory expectations. Roig’s work extends beyond analysis, calling for systemic change and the integration of intersectional perspectives into political and societal decision-making.

These approaches are further translated and adapted by various scholars and practitioners in different formats and contexts in architecture: to question hegemonic structures and foster agency, Helene Frichot presents a framework for linking feminist theory and architecture in her book How to Make Yourself a Feminist Design Power Tool (2016). It is designed as a guide to help architects align their work and thinking based on feminist principles. Brady Burroughs and Afaina de Jong published the zine Lorde for Architecture Students in 2023 as part of the series Feminist Thinkers for Architects, in collaboration with CLAIMINGSPACES* and architecture students from TU Wien. The zine encourages architects and educators to actively imagine spaces of freedom and to critically challenge existing structures.

While decolonial perspectives have been discussed in English-speaking academic discourses since the 1980s (hooks 1984; Lorde 1984), there is comparatively less work on these topics in the German-speaking context – particularly within the field of spatial planning. Topics such as intersectionality and decolonisation have only recently gained broader attention (Roig 2022; Zwischenraum-Kollektiv 2017). However, the link between spatial practices and intersectionality remains largely unexplored.

By drawing on the works of Audre Lorde, bell hooks and Emilia Roig, an intersectional lens for critical reflection is developed (Crenshaw 2019: 12). This lens is centred on personal experience, which is then subjected to analytical scrutiny, from which insights are derived and structural inequalities are rendered visible. This methodological approach facilitates not only a personal perspective on discrimination and oppression but also a more profound examination of societal power relations.

2.4 Knowledge gaps

As previously outlined, there is extant research on participation processes and governance structures in living labs that discusses the roles of different actors in detail (Hernberg 2022; Hossain et al. 2019; Nyström et al. 2014). However, there are only a few specific theories addressing intermediary actors and their roles in relation to their social positionalities within living labs. Roles in living labs are still largely reduced to expertise and motivation – i.e., which professional and/or functional areas are represented. Social positions, however, are not yet linked to these roles, despite the fact that they are inextricably intertwined in practice. Although multi-roles and the capacity for code-switching are key functions in living labs, there remains a significant knowledge gap regarding the critical reflection of these roles and the ability to navigate between them. By analysing roles in living labs through the lens of intersectional theory and the work of the three selected positions, it becomes possible to explore how different social positionalities – along the lines of gender, class, ethnicity or physical ability – shape the distribution of roles and responsibilities in such settings: Who takes on the conceptual, creative or strategic work? Who is responsible for care work and maintenance? Who can afford to do – or not do – certain tasks? Who is able to switch between roles and who is compelled to do so? Against this backdrop, the research examines the extent to which the emotionally demanding work of code-switching in living labs falls into the category of unseen work by asking which additional roles emerge beyond the established ones, how code-switchers operate – including the challenges and opportunities they encounter – and how their situated knowledge can be made visible. Owing to multiple layers of responsibility, individuals in marginalised positions are structurally compelled to manage a disproportionate number of code-switching interfaces compared to their non-marginalised counterparts. This emotional and cognitive labour contributes to the maintenance of existing power relations by positioning marginalised individuals as intercultural mediators – while other groups benefit from this additional, invisible labour without having to perform it themselves.

3. Methods

3.1 Dialogue-based reflection practice

Using semi-structured peer interviews – conducted both with and by the authors, two practitioners who founded a collaborative project – the focus lies on what was learned within these projects, the experiences made and the significance of multi-roles in these processes. Peer interviewing, understood as a dialogical and reciprocal format (Bergold & Thomas 2012), enables the articulation of tacit knowledge, informal practices, and forms of emotional labour often overlooked in conventional interviews. The mutual understanding and appreciation of different backgrounds were a necessary precondition for developing professional and political solidarity and for creating a space of emotional trust, intimacy and respect (hooks 1994: 137). Now working within academic contexts, the authors are in a position to critically reflect on their earlier roles and assess how these shaped their scholarly work, while also interrogating current research approaches in light of practical experience. This reciprocal interview format can generate insights beyond one-sided questioning and helps uncover unconscious biases, challenge assumptions and co-develop concepts that more effectively bridge theory and practice. Such a dialogical approach can be understood as an experimental research method that deliberately diverges from conventional interview settings and can be situated within broader traditions of interpretative social research (Rosenthal 2018) and case study methodology (Stake 2010). It enables a form of collaborative knowledge transfer in which not only is data collected but new ways of thinking are co-created. In doing so, it opens up a space for reflection, knowledge generation and potentially even the development of new research questions situated at the intersection of practice and academia.

3.2 Creating a common cognitive space

Both individuals share similar practical experiences but come from different cultural backgrounds. While both have marginalised identities, their social starting points differ – they identify as people of colour, migrant, women, queer and working class. This makes their peer interview particularly compelling, as it not only enables reflection on shared experiences but also brings to light differences in their social positioning, access to resources, and entry into certain spaces and networks. The reciprocal interview thus offers a unique opportunity for intersectional analysis. While traditional interviews often imply a hierarchical structure between interviewer and interviewee, this setting allows for mutual reflection on power, positionality and epistemic authority and resonates with intersectional feminist epistemologies that foreground embodied difference (Ahmed 2017).

In line with Donna Haraway’s concept of ‘situated knowledges’ (1988), this methodological choice recognises that knowledge is always shaped by embodied, cultural and social positions. Objectivity here is not understood as detachment but as a conscious engagement with the conditions of one’s own knowledge production (Haraway 1988). The interview thus does not neutralise the participants’ experiential backgrounds but deliberately integrates them as epistemic resources.

The method gains particular relevance because it enables questions of structural marginalisation and relative privilege to be addressed not only theoretically but also experientially. This draws on the idea of experiential knowledge as an epistemic resource that mediates between different domains of practice and thought. The ability to translate between material practices, social contexts and conceptual categories is not theoretically derived but practically acquired – and here becomes productive for analysis (Haraway 1988).

There remains a risk of confirmation bias – i.e., of confirming shared assumptions rather than critically questioning them. The authors are aware that familiarity may lead them to insufficiently problematise certain issues, either because they are taken for granted or because uncomfortable aspects are unconsciously avoided. This reflexive awareness aligns with approaches that view subjectivity not as a methodological deficit but as a source of scientific quality (Haraway 1988; 2016). By acknowledging the risks inherent in their positionality, the authors take responsibility for the epistemic conditions under which their knowledge is generated.

At the same time, the limitations of the approach must be acknowledged. The small number of interviews and the close familiarity between the participants pose the risk of overlooking or insufficiently problematising certain aspects. Furthermore, the findings cannot be generalised in the conventional sense; rather, they should be understood as context-specific, situated and reflexive insights. Precisely by making these limitations explicit, the method gains credibility: it underscores that the aim is not to produce representative data but to critically explore experiential knowledge and epistemic positionality.

It must also be acknowledged that the empirical basis of this approach is limited, as only one reciprocal interview was conducted. However, this conversation did not take place in isolation: it was embedded in a long-standing exchange between the two researchers, who had already engaged in numerous conversations with each other as well as with a variety of actors in different living labs, both before and after the recorded interview. These ongoing dialogues inform the analysis and provide a broader experiential context, so that the single interview functions less as a stand-alone data point and more as a focal condensation of a much wider set of shared reflections and empirical encounters.

3.3 Mapping role dynamics

In order to analyse the diversity of roles and their assignment dynamics within living labs, a mapping method was applied that visually captures the relationships between actors and their respective roles. This approach allows for the identification of recurring patterns as well as structural influencing factors within living labs. The mapping process was carried out iteratively during the interviews, following the concept of the matrix of domination developed by Patricia Hill Collins (1990), which accounts for multiple forms of oppression:

[T]he matrix of domination refers to how these intersecting oppressions are actually organized. Regardless of the particular intersections involved, structural, disciplinary, hegemonic, and interpersonal domains of power reappear across quite different forms of oppression.

The matrix of domination allows individuals to identify themselves in relation to various social classifications such as race, gender, ethnic background and economic class. This helps to reveal the complexity and overlap of these levels and is one of the tools that can be used to represent an individual’s position (Hill Collins 1990: 274).

4. Case studies

Both case studies can be understood as living labs in the sense of the call for papers: real-world environments where spatial, social and institutional experiments are tested in collaboration with diverse actors. While Quartier:PLUS operates as a neighbourhood-based lab embedded in the everyday life of Schwarzer Berg (Quartier:PLUS 2023), Österreichischer Platz in Stuttgart exemplifies an urban experimental lab that temporarily transformed an infrastructural void into a discursive and participatory arena (Stadtlücken 2022). In both cases, living lab methodologies unfold through mediation, co-creation and spatial interventions, enhancing civic resilience and enabling new forms of collective urban imagination.

4.1 Quartier:plus

The Quartier:PLUS initiative aims to revitalise the Schwarzer Berg neighbourhood in Braunschweig through integrated action and active dialogue, with the overarching goal of strengthening community ties and negotiating new pathways towards a solidaristic urban coexistence (Tarik 2021). The district, built in 1964, features a diverse mix of housing types – from single-family dwellings to studio apartments – inhabited by a heterogeneous population from various social backgrounds. For several years, Schwarzer Berg has faced significant challenges, including high vacancy rates, insufficient local services, the deterioration of public spaces and buildings, affecting the shopping centre and surrounding housing complexes (Springer 2023).

This situation laid the groundwork for activating and co-developing the neighbourhood in collaboration with residents starting in spring 2021. A vacant retail unit within the shopping centre was repurposed as the Quartier:HAUS, envisioned as a future space for exchange and encounter (Lux 2023).

Beyond the hosting of events, workshops, and festivals, the Quartier:HAUS has since evolved into a container of local knowledge – where ideas, needs, visions, fears and experiences are gathered and discussed. Operating as an interface between residents, policymakers, academics, property owners, civil society and the city administration, this knowledge was translated and communicated in multiple directions by the project staff (Tarik et al. 2023). Their ability to navigate and mediate between professional, academic and civic realms was crucial for making these exchanges possible. As trained architects embedded in academia and in the everyday life of the neighbourhood, they took responsibility for project leadership, coordination, administration and strategy, as well as the internal organisation of the Quartier:HAUS and its network of volunteers. With a refined understanding of spatial design, they introduced new atmospheres to the neighbourhood – especially within the Quartier:HAUS – and implemented targeted spatial interventions to stimulate visual and functional transformation (Lux 2023). Participation processes were not only facilitated but also materially supported through the creation of temporary ‘living rooms’ in public space, offering low-threshold opportunities for dialogue and co-creation. These creative interventions contributed significantly to community development, illustrating the value of interdisciplinary approaches in neighbourhood revitalisation (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Quartier:HAUS as a space for encounter and participation, 2022.

Photo: Yamen Abou Abdallah.

4.2 Österreichischer platz

For many years, Österreichischer Platz in Stuttgart remained a neglected urban space, dominated by traffic infrastructure and lacking public amenities. In 2016, the interdisciplinary collective Stadtlücken e.V. – founded by young designers and architects – identified the transformative potential of this underused site and began advocating for its redesign and activation (Stadtlücken e.V. 2022).

Located beneath the Paulinenbrücke in the heart of the city, the area had long served primarily as a parking lot. It was perceived as unwelcoming and unsafe, acting as a physical and social barrier between neighbourhoods (Landeshauptstadt Stuttgart 2018). In autumn 2016, Stadtlücken launched a series of performative actions to highlight the site’s potential, including a pop-up kiosk selling souvenirs for a square that did not yet exist. These symbolic interventions prompted the City of Stuttgart to reconsider the area, which had been leased to a private parking operator until spring 2018. Following growing public interest, the city, in cooperation with Stadtlücken and based on their concept, opened the space as a testing ground for alternative, non-commercial uses.

Various usage concepts were trialled with the support of Stadtlücken, which coordinated temporary activations directly on site – ranging from participatory actions to cultural events (Figure 2). As a result, Österreichischer Platz evolved into a social meeting point and platform for urban-political discourse. The project received national recognition and won first prize in the urban space category at the federal competition Europäische Stadt: Wandel und Werte – Erfolgreiche Entwicklung aus dem Bestand (BMI 2018).

Figure 2

Urban experimental site Österreichischer Platz, 2018.

Photo: Stadtlücken e.V.

The initiators – trained in architecture and design – played a key role in implementing spatial interventions with provisional urban furniture, lighting, and infrastructure (Noller et al. 2024). Their cultural programming included discussions, screenings, and collaborative workshops aimed at inclusive interactions. Residents, professionals and stakeholders co-developed visions for long-term use. Over time, the initiators became mediators and moderators, facilitating dialogue and designing participatory formats. They also advocated for the inclusion of marginalised populations, such as the unhoused and those in substitution programmes, amplifying their voices in urban discourse.

In dialogue with the municipality, Stadtlücken operated as a critical interface between civil society, politics and administration – negotiating implementation strategies and permissions. The project showed how temporary, low-threshold interventions can unlock new perspectives for overlooked urban spaces – if accompanied by committed mediation.

Between 2018 and 2020, Österreichischer Platz was reactivated as a vibrant social space and discursive arena for reimagining the city. With municipal support, the project was initially poised for long-term institutionalisation (Ayerle 2020). However, insecure planning conditions and the COVID-19 pandemic placed significant strain on the team. The project, reliant on voluntary engagement, could not be sustained in its original form. Though the city showed interest in continuing it, support structures were slow to follow. Eventually, the project continued in a more formalised format – still valuable but no longer reflecting the open, experimental spirit envisioned by Stadtlücken (Stadt Stuttgart 2021). Nevertheless, it contributed lasting momentum towards more sustainable and inclusive urban development in Stuttgart, proving that urban voids can become productive sites for negotiating collective futures (Wesely 2021).

5. Analysis and critical reflection

5.1 Contextualisation

The two interviews highlight key aspects of bottom-up living labs, showing both their potential and their challenges. The Quartier:PLUS and Österreichischer Platz projects demonstrate how locally embedded initiatives involving civil society actors emerge and operate. Both cases reveal the structural conditions that shape participation and power dynamics. A recurring theme is the significance of multi-roles – individuals assuming diverse responsibilities within the projects and navigating unequal access to decision-making based on their social positioning (Hill Collins 1990: 274). This often includes invisible translational work between contexts (hooks 1994).

Quartier:PLUS developed from personal motivation, academic research, and dialogue with local residents. Informal networks and committed citizens were vital to its realisation, underscoring the role of social capital and collective mobilisation in participatory urban development. A central element was the creation of a physical meeting place for exchange, with events like flea markets helping to build trust among diverse actors. The project’s eventual institutionalisation through public funding shows that participatory approaches need long-term support to create lasting impact.

The Österreichischer Platz project also emerged from a combination of personal experiences and academic research. The initiators had witnessed the threat to public space and its central role for democratic coexistence during their time in London and Istanbul. The project aimed to raise awareness of the importance of public space across different neighbourhoods. Strategic interventions, the activation of informal networks, and the opening of the square as an experimental field for encounter and exchange in the city centre played a crucial role in this process.

5.2 Multi-role practices

A key pattern that emerges in both interviews is the assumption of multiple roles by individual actors. The initiator of Quartier:PLUS was not only the project lead but also a resident with a migration background, a trained architect with a focus on urban research, and a mediator between residents, the neighbourhood association and the municipal administration. She took on conceptual, organisational and communicative tasks, some of which required particular forms of translational work shaped by the migrant-influenced context. As Ayat Tarik put it in the interview, ‘I think it’s not such a clear-cut thing where you can say: Now I’m a planner. Or now I’m a facilitator. Instead, you’re constantly slipping into different roles’ (Interview with Ayat Tarik, conducted on 17 March 2025).

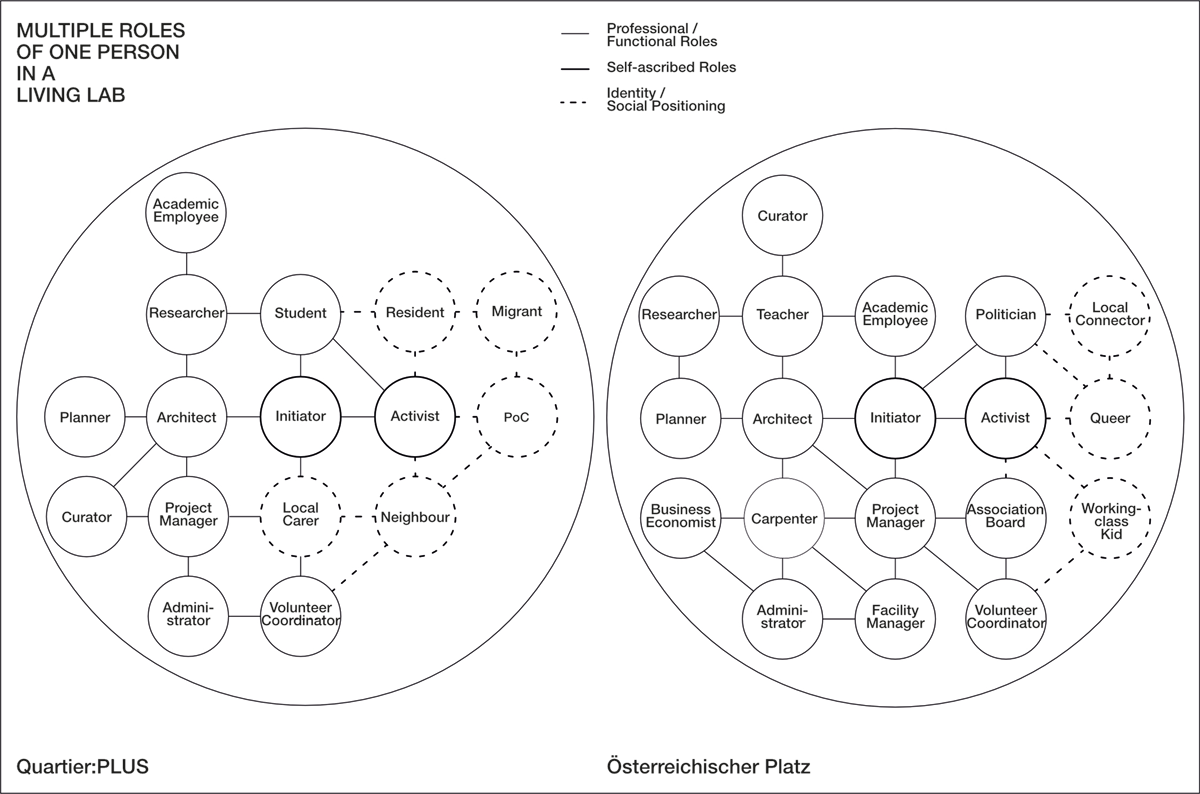

While in Quartier:PLUS multiple roles primarily manifested in the assumption of various responsibilities within a single project, the example of Österreichischer Platz illustrates how multi-role positions can extend beyond the boundaries of a specific initiative (Figure 3). Not only were the project’s initiators part of the core team of the living lab but they also acted as intermediaries across different scales and groups. With interdisciplinary backgrounds – including carpentry, architecture, academic research, and project coordination in another urban lab at the Institute of Urban Design, as well as an elected position on the district council – they bridged the gaps between civil society, political and academic interests and the capacities of the municipal administration. Their mediating position was also reflected in their communicative approach: ‘We speak a simple language, and we only ask questions, we don’t give answers’ (Interview with Hanna Noller, conducted on 17 March 2025). This attitude illustrates a deliberate strategy of accessibility and openness, aimed at fostering dialogue across different social and institutional contexts.

Figure 3

Illustration of the multiple roles.

Source: Authors.

Such dual and multiple role constellations are characteristic of participatory and collaborative projects, in which individuals are often required to mediate between diverging interests and positions as well as across different scales and practices. As Ayat Tarik explained, ‘Sometimes I simply switched roles […] I also made use of the university’s resources because it should go where it’s actually needed’ (Interview, Tarik 2025).

This multiplicity can be highly productive and, in fact, enabled the projects in the first place. However, as both interviews clearly reveal, it also entails challenges: the simultaneous assumption of strategic, administrative and facilitative responsibilities can lead to overload and carries the risk that certain roles remain under acknowledged or undervalued. ‘There were moments when I no longer felt comfortable,’ Tarik recalled, ‘because I had the feeling that I was expected to meet demands I couldn’t – or didn’t want to – meet’ (Interview, Tarik 2025).

In the worst-case scenario, this unreflected accumulation of responsibilities can have negative effects on individual well-being, as illustrated by the case of Österreichischer Platz. In both projects – which were driven by voluntary engagement – overlapping roles, the coordination of unpaid work and the translational labour that accompanied it required a high degree of personal commitment. The boundaries between roles – between professional expertise and private involvement – became increasingly blurred. ‘I was, on the one hand, the resident who started it all, then the student who was constantly jumping between worlds. And then I was […] the one taking care of things on site’ (Interview, Tarik 2025).

5.3 An intersectional perspective

In both cases, the intersectional lens makes an additional dimension visible: the intersectional perspective on multi-role practices. This perspective goes beyond the observation that individuals assume different tasks and roles, by highlighting how social positioning – such as gender, class or institutional affiliation – shapes access to decision-making processes.

For example, the interview related to the case of Österreichischer Platz reveals that established actors with institutional knowledge and access to networks enjoyed distinct advantages, while marginalised groups remained largely invisible and faced structural barriers to participation. As Ayat Tarik noted, ‘Of course not everyone can afford to volunteer or to be active in the first place’ (Interview with Ayat Tarik 2025). This highlights a critical limitation within the participatory promise of living labs: those already embedded in existing power structures are more easily able to engage in planning processes and participate in decision-making. In contrast, those affected by economic insecurity or lacking institutional ties are often relegated to informal or supportive roles – or are excluded entirely. Socially disadvantaged individuals must routinely perform additional translational work simply to gain access to planning and decision-making spaces and to exert any influence within them. Such dynamics resonate with Lorde’s reflections on the contradictory roles imposed on multiply marginalised identities, who are often expected to contribute while being simultaneously excluded from shaping the terms of participation (Lorde 1984: 113).

Another example of this intersectional insight is the unequal visibility of different forms of labour within the projects. While strategic and design-related decisions were often rewarded with recognition and appreciation, practical and emotional work – such as mediating between groups or maintaining the physical and organisational infrastructure – frequently remained invisible, taken for granted as background tasks:

But clearly, without that person at the centre who actually translates everything – from ‘what’s the goal’ to ‘what’s the next concrete step’, even if it’s just buying the cable reel – that, to me, is crucial in these labs.

(Interview, Noller 2025)

Because translational work in these projects ‘is often taken for granted or carried out on the side’ (Interview, Noller 2025), it frequently goes unnoticed that such work must occur not only between disciplines but also across social positions – in all directions. This invisible labour of code-switching is essential to the functioning of these initiatives and to the success of living labs, yet it is rarely valued, recognised or even consciously acknowledged. Marginalised individuals gain a critical perspective on power by moving across social worlds. hooks frames this code-switching and reflection on contradictions as marginalised knowledge and a form of resistance (hooks 2015: 149–150).

Actors who aim to make planning processes accessible to everyone – regardless of their own social position – often take on multiple roles simultaneously. They must shift between institutional, professional and everyday contexts, translating not only knowledge but also expectations, needs and norms. While formal and strategic contributions may be rewarded with visibility and authority, relational and emotional labour, organisational maintenance and the care-oriented work of keeping a space open and accessible often remain unacknowledged. These blurred boundaries between tasks, roles and positions point to the deeply interwoven dynamics of social inequality within participatory urban development.

While some actors find code-switching easier because they had to learn it early in life, as Ayat Tarik reflected: ‘I grew up switching between languages and contexts, because of my migration background. I don’t even notice it anymore’ (Interview, Tarik 2025); others develop this skill only through their engagement in such projects – and come to realise how much additional labour and emotional strain it entails (Lorde 1984). Those who have been navigating multiple cultural or social contexts from a young age often use this ability like a trained muscle – naturally and often unconsciously. In contrast, those who acquire the practice within the project experience role-switching more consciously and often perceive it as emotionally demanding and exhausting.

At Schwarzer Berg, the team placed particular emphasis on involving residents from diverse social backgrounds. Here, the diversity already presents within the project team proved to be a major asset: it encouraged more residents to engage and share their perspectives. However, the person seen as the most relatable or accessible point of contact often automatically took on additional, invisible labour. ‘It’s sometimes really exhausting,’ Ayat Tarik reflected, ‘because I feel like I’m being pulled from all sides’ (Interview, Tarik 2025).

At Österreichischer Platz, specific formats were developed to make the project accessible to as many people as possible. Yet it quickly became clear where the limits of such ambitions lie when the work is carried out entirely on a voluntary basis. As the project grew in scale and visibility, so did the demands of coordination and communication. ‘The more people got involved,’ Hanna Noller noted, ‘the more you had to communicate and organise’ (Interview, Noller 2025).

The project also produced an unplanned but positive side effect: around the initiative, further actors – including some highly marginalised groups – were inspired to take action themselves and launch their own grassroots projects (e.g. St Maria als, PauleClub, HarrysBude).

At Quartier:PLUS, the work has been able to continue thanks to sustained institutional support from the City of Braunschweig. Nonetheless, the process of institutionalisation raises new questions about who takes on the often-invisible tasks – and who is in a position to perform these roles, particularly those that require the ability to code-switch. This skill, which is essential in participatory urban development, is still largely unacknowledged in formal education systems and therefore not systematically taught. As Hanna Noller reflected: ‘You can’t just read a book and then do participation – you have to do it and gain experience […] You can only learn it by doing. I think it’s like a craft’ (Interview, Noller 2025).

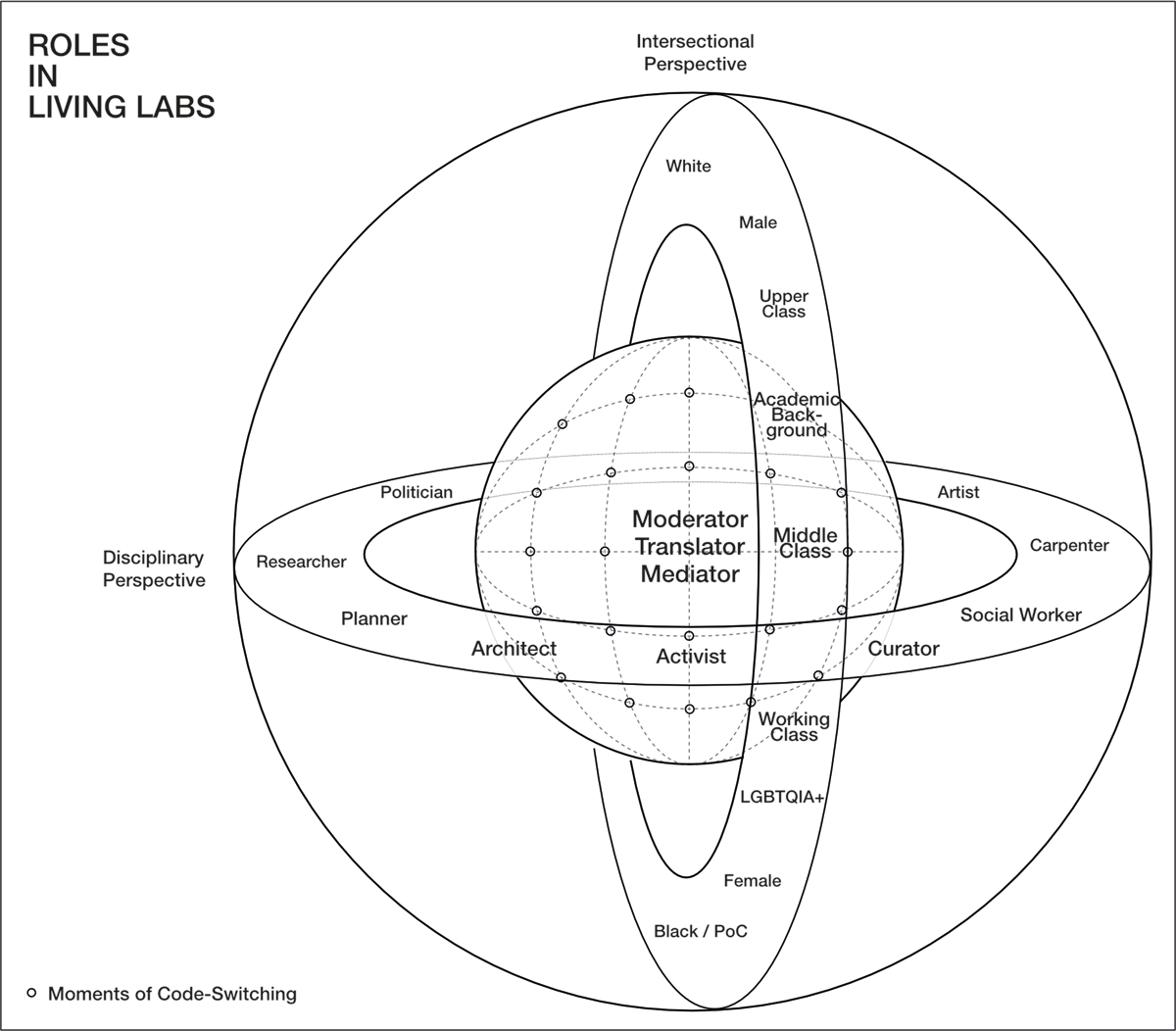

5.4 Intersectional role dynamics

The visualisation of roles within living labs (Figure 4), developed during the interview process, highlights a third dimension of dual and multiple role constellations – one that becomes visible through the lens of intersectional theory (Crenshaw 2019: 12). It reveals the complex entanglements of social positioning that significantly shape inclusivity and justice in urban development. Although the visual only captures a selection of roles from the two case studies and is by no means exhaustive, the mapping clearly demonstrates that participatory processes are always embedded in social hierarchies and forms of belonging. Moderation, mediation and translation must take place not only across disciplines but also across different social positions. These roles emerge as key mechanisms in striving for more equitable processes of negotiation. Although the figure illustrates the diverse roles exemplified by both projects, it does not account for additional dimensions such as private relationships.

Figure 4

Roles in living labs.

Source: Authors.

The lower one stands in the hierarchy, the less visibility, voice, and empathy one is granted. The end of oppression, utopian as it may sound, is nothing more than a shift in consciousness: towards a reality in which all of us are seen, heard, and respected—not just a privileged few.

6. Conclusions

6.1 Multi-role practices as a central element of participation

The interviews reveal that dual and multiple roles are central to participatory living labs and urban development processes. Actors frequently assume several responsibilities at once – as organisers, mediators and strategic planners. However, people are differently positioned by social and institutional structures, which affects their access to decision-making processes. While Quartier:PLUS, as a locally embedded project, illustrates how urban development can emerge from practice, the case of Österreichischer Platz highlights the limits of participation. Participation is not automatically inclusive – it is shaped by economic, social and institutional conditions. An intersectional perspective helps to critically reflect on these dynamics and to work towards more equitable structures within living labs.

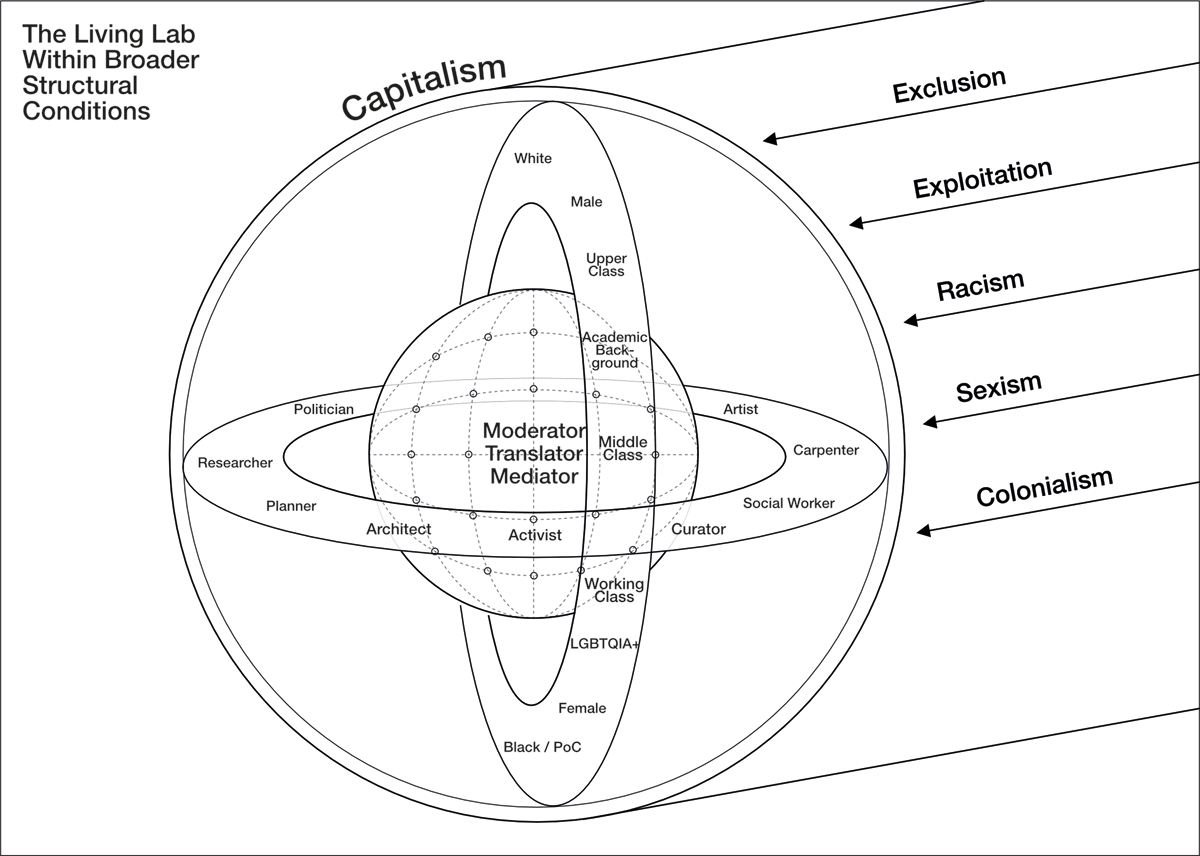

During the conversations about roles and interactions in the living labs, sketches were created in parallel to document emerging role allocations. These sketches were then digitally overlaid and compared to visualise overlaps, gaps and asymmetries of power. From this process, Figure 5 synthesises the different perspectives and makes visible the coexistence of professional functions, self-ascribed roles and social positionings.

Figure 5

The living lab in the context of overarching structural conditions.

Source: Authors.

6.2 The reproduction of inequality

The findings of this study underscore the importance of explicitly acknowledging and critically examining multi-role dynamics in living labs. However, their embedding within existing systemic logics runs the risk of reproducing marginalising structures, like social exclusion and exploitation (Ahmed 2012), racism and sexism (Lorde 1984: 108), capitalism and colonialism (Quijano 2000: 540). People who, owing to their social positioning, already take on multiple roles and perform translational work across different contexts often find themselves burdened with additional, frequently invisible, labour – even within participatory settings.

Participatory processes must be understood as dynamic spaces in which diverse perspectives actively contribute to shaping sustainable visions of the future. At the same time, a fairer distribution of labour and responsibility requires structural changes within planning and participation systems.

6.3 Code-switching as translational competence

The ability to code-switch emerges as essential for collaborative and transformative projects, as it facilitates communication across different actor groups and opens new spaces for mutual understanding. Translational labour associated with code-switching can create bridges where boundaries previously existed and foster integrative processes across diverse contexts. The goal should be to create greater visibility – and better conditions – for this work within living labs. It is therefore vital to further investigate this capacity within the context of collaborative urban initiatives – especially in terms of how it can be learned and practised without being solely a reactive response to marginalisation or structural pressure to adapt. What conditions and educational paths make it possible to cultivate code-switching as a conscious competence, without associating it with a loss of authenticity, oppression or a requirement to conform to dominant norms? This question remains central to future research. It opens up a much-needed dialogue between theory and practice – one that has thus far remained underexplored.

6.4 Towards structural change

In the broader societal context, it is precisely this translational labour that holds potential for addressing increasing complexity and social polarisation. Democracy is not at an end; rather, a more complex society requires new forms of negotiation, translation and mutual understanding (Mounk 2022). This work must no longer be treated as a voluntary side activity but must be institutionally supported and socially recognised. Otherwise, the political imbalances we are currently witnessing may deepen further. Living labs of this kind are not merely experimental spaces – they are democratic infrastructures urgently needed to address global challenges collectively and equitably such as climate change and social and political transformation. A diverse but just world will not be possible without translational work, or, in the words of Donna Haraway, it is about ‘staying with the trouble’ – not avoiding it but forging new connections through it.

7. Limitations and tentative findings

This study is based on two in-depth case studies and therefore cannot provide generalisable conclusions about all living labs. The findings are shaped by the positionalities of the interviewed actors and by the specific sociopolitical contexts of the projects, which limit their transferability. Moreover, the reliance on self-reported experiences highlights subjective perspectives while leaving structural blind spots, particularly regarding voices that remained less visible or excluded. Despite these limitations, the cases point to tentative findings: multi-role practices and translational labour emerge as central mechanisms of participatory urban development. They make collaboration across institutional and social boundaries possible but also risk reinforcing inequalities when the invisible labour they entail remains undervalued. The intersectional perspective proves crucial for revealing how power dynamics, social positioning and access to resources shape participation. These insights underscore both the transformative potential and the systemic constraints of living labs and open up avenues for further comparative and longitudinal research.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Yahmani Blackman, whose impulse and encouragement were pivotal in prompting a deeper reflection on our own practice. Further thanks go to the initiatives Quartier:PLUS and Stadtlücken for their inspiring collaboration and all the actors and supporters involved, to Tatjana Schneider and the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture and the City (GTAS) at TU Braunschweig for their academic support.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Data availability

The qualitative data underlying this study consist of confidential, dialogue-based reflections from the peer interviews as well as internal project documentation. Owing to their personal character and the trust framework in which they were generated, the data are not publicly accessible.

Ethical consent

The study is based on semi-structured peer interviews between the authors, complemented by project documentations and practical experiences and informed by exchanges with actors from similar initiatives. As outlined in the methods, the peer interview was designed as a dialogical, co-research practice rather than conventional data collection; thus, the associated risk was minimal. Both authors explicitly consented to the process and engaged in continuous reflection throughout. Particular care was given to transparency, mutual responsibility and respectful handling of personal and positional reflections. No formal ethics approval was required due to the self-reflective and co-creative nature of the approach.