1. Introduction

1.1 Demolition, housing and circular economy policy in Rotterdam

A growing, increasingly urban, population in the Netherlands requires solutions to challenging social and spatial housing issues. Urban renewal is the political and material development to solve these issues, with a significant role for the demolition of social housing. Social housing is slated for demolition for many reasons, involving technical, social and architectural issues (Deboulet & Abram 2017: 150–154). In most European countries, the existing post-war social housing estates may have reached the end of their technical lifespans. This article considers the case of Rotterdam, the Netherlands, as it exemplifies the tensions that exist between city development and the social life of tenants.

Rotterdam aims to grow its housing stock to accommodate the estimated growth of the city. It has currently roughly 310,000 housing units, of which around 120,000 (in 2020) are owned by social housing corporations. Approximately 61% of the housing corporation stock is owned by the four largest corporations. According to the city’s main housing policy document, Housing Vision 2030 (Woonvisie 2019: 1), the housing stock should grow by at least 30,000 to adjust to population growth and to keep the local housing market balanced in terms of quality and price levels. Urban renewal in Rotterdam is a priority issue, as large parts of the city contain housing that is technically obsolete, badly maintained and with a low energy rating. Urban renewal in Rotterdam is framed as improving the balance between different price categories of housing (Woonvisie 2016: 17).

The main research question addressed is: What discourses surround and influence Rotterdam housing policy, with a focus on demolition of social housing? The objective is to understand where the emphasis on demolition of social housing comes from and how different policies affect this policy goal.

This article examines (1) the role of local policy in the production and demolition of social housing and (2) the focus on social mix policies in housing policy. It considers how the emerging circular construction policy in Rotterdam could potentially backfire, due to existing plans for the demolition of some social housing. Social mix policy is claimed to achieve greater (tenant) diversity and reduce ‘neighbourhood effects’, e.g. lack of social, ethnic and economic diversity (van Ham et al. 2012). This policy idea has been widely criticised but appears entrenched in housing policy (August 2019; Bolt et al. 2010). Social mix often coincides with the demolition of (social) housing of disadvantaged and/or vulnerable groups (August 2019; Deboulet & Abram 2017; Levin et al. 2014). This study adds to an understanding of social mix policies and demolition by highlighting the role of social housing corporations. It will also show how the emerging discourse around the circular economy in the urban environment adds a new challenge to urban renewal policies.

Housing policy in Rotterdam has been focused on making Rotterdam more attractive, providing housing and reducing social problems. The implementation of Housing Vision 2030 shows that the primary goal of the city of Rotterdam and the corporations is to bring more diversity in housing (Woonvisie 2016: 17–18). The policy associated with this goal is the Administrative Agreement Neighbourhoods in Balance (Bestuurlijke overeenkomst Wijken in Balans; BOK 2019). Its implementation is the so-called Area Atlas 2020 (Gebiedsatlas 2.0 2020). The Area Atlas shows how and where social housing should be reduced. The housing policy goals of Rotterdam involve (extensive) demolition as well as renovations and transformations. In a historical context this is not a new development, as Dol & Kleinhans (2012) show. Rotterdam’s circular economy focuses explicitly on the construction sector and its material flows. The core goal of this policy is the reduction of the city’s emission impact and waste reduction (Rotterdam Circulair 2019: 14–16).

From a socio-demographic point of view the ‘unbalanced’ areas are seen as less desirable (by the municipality) because they are characterised by relatively high unemployment, socio-economic problems such as drug use, low educational achievement, and crime. This is a characteristic of social housing that extends beyond Rotterdam and the Netherlands (van Kempen & Bolt 2009; Deboulet & Abram 2017). The policy goal is to achieve neighbourhoods with a better social mix. The central policy instrument Dutch municipalities must employ to achieve this goal is the ‘performance agreement’ with social housing corporations and their tenant organisations (prestatieafspraken). The performance agreements address quantitative and qualitative aspects of the housing stock, environmental issues (such as energy efficiency) and the financial framework of the housing corporations’ goals.

1.2 Policy arguments for urban renewal

The current housing policy follows what Musterd & Ostendorf (2008) call the ‘third generation of urban renewal’, in which the main social issue is declining ethnic and social integration, to which the appropriate policy action is to improve the social mix of city areas. This policy goal is criticised by the authors for being based on the ‘shared beliefs’ of policymakers rather than on empirical fact (Musterd & Ostendorf 2008: 78). Their study highlights the divergence of discourses between policymakers and citizens (who see their area of living threatened). There is nonetheless little empirical evidence for the assumed benefits of social mix. These are often based on policymakers’ preferences and beliefs (Bolt & van Kempen 2013). Among policymakers’ arguments for social mix are the effects on social cohesion, local housing careers and improving social mobility. Local housing careers are mostly an opportunity for middle-income households (van Kempen & Bolt 2009). Deboulet & Abram (2017) study the interaction between social mix policies and demolition in France and England and find that in many cases demolition occurs in areas where there are many socio-economic problems with little participation in urban planning by the inhabitants. August (2019) argues that social mix is based on assumptions that do not empirically hold and are biased: social mix takes fundamental inequality as a given rather than something that should be problematised.

Rotterdam aims for a better balance in neighbourhoods by 2030. The implication is a radical reduction of as many as 10,900 social housing units (Woonvisie 2019: 6), based on the city’s assessment of an oversupply of social housing. Divestment of social housing to private parties and renovation of social housing are other options to transfer housing to other price classes. Since 2017, the social housing stock has already declined greatly through real estate value increases (Voortgangsrapportage Woonvisie 2030, 2022). The primary reason for demolition is the technical condition of the housing unit (Woonvisie 2016: 1). However, the goal of diversification is quite explicit in the Area Atlas.

This sketch of recent Rotterdam policy and housing developments shows that housing policy connects to many other social and policy issues.

2. Analytical framework, methodology and data

2.1 Analytical framework

The view of policymaking employed here is based on Fischer, who argues that policymaking is:

a constant discursive struggle over the definitions of problems, the boundaries of categories used to describe them, the criteria for their classification and assessment, and the meanings of ideals that guide particular action.

This is a policy analysis approach to study complex policy fields with many actors and many ‘policy artefacts’ (policy documents, statements, reports). In policymaking stakeholders often have differing interpretations of the social meaning of policy, which can lead to tensions. Fischer argues that interpretations of social meaning can be found in ‘policy stories’. In this approach, language and discourses have a role in structuring social action.

Fischer’s framework is preferable to other analytical traditions, e.g. Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) (Sabatier 1998), in that it sensitises the scholar to conflicts, tensions, struggles, social meaning and power issues within the institutional setting (Fischer 2003: 71–114). Policy analysis approaches used to study policy change are less suited to recognise tensions in and between policies because they often assume rationality as the basis for policymaking, and policy changes through outside shocks rather than interaction between ideas and values. It also moves away from policy as a means-end instrument. Fischer (2003: 33) argues the focus should be on the appropriate policy community. In this study, the policy community consists of stakeholders to the housing policy: at the institutional level the municipality, housing corporations and tenant organisations (the ‘triangle’), but also tenants who experience the effects of policy.

2.2 Methodology

This is a case study of the social housing policy of Rotterdam as expressed in policy artefacts. According to Yanow (2000: 22), an interpretive policy analysis should follow the following four steps.

First, one should identify the main carriers of meaning (language, objects, acts) that are relevant for the policy actors. The artefacts of this housing policy are shown in Table 1. Most of the documents in Table 1 deal with issues beyond social housing.

Table 1

Policy artefacts.

| NAME | THEMATIC FIELD | LEVEL | TYPE | LEGAL BASIS | PERIOD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woonvisie 2030 | Housing policy | Municipal | Policy document | Woningwet 2015 | 2016–30 |

| Woonvisie 2030 Addendum | Housing policy | Municipal | Policy document | Woningwet 2015 | 2019–30 |

| Voortgangs-rapportage Woonvisie 2030 | Housing policy | Municipal | Policy document | n.a. | 2018 |

| Volkshuisvestelijke Prioriteiten | Housing policy | National | Policy document | Woningwet 2015 | 2021–25 |

| Bestuurlijke Overeenkomst Wijken in Balans (BOK) | Housing, social policy | Municipal | Agreement between the municipality and corporations | Private law contract | 2019–30 |

| Omgevingsvisie Rotterdam | Environmental policy | Municipal | Policy document | Omgevingswet | 2021 |

| Van Zooi tot Mooi (Rotterdam Circulair 2019) | Environmental policy | Municipal | Policy document | Rotterdam Council decision | 2019 |

| Kantelpunt (Rotterdam Circulair 2021) | Environmental policy | Municipal | Policy document | Rotterdam Council decision | 2021 |

| Midterm Review NPRZ | Housing, social policy | National/municipal | Policy document | Multilevel policy agreement | 2022 |

| Green deal Verduurzaming Betonketen | Environmental policy | National | Policy agreement | Private law contract | 2011 |

| Betonakkoord | Environmental policy | Sectoral | Sectoral agreement | Private law contract | 2018 |

| Transitieagenda Circulaire Bouw | Environmental policy | National | Sectoral agreement | Grondstoffenakkoord (2017) | 2018 |

| Metabolic (Rotterdam Urban Mine) | Environmental, economic policy | n.a. | Consultancy report | n.a. | 2021 |

| Metabolic Materiaalstromen | Environmental, economic policy | n.a. | Consultancy report | n.a. | 2018 |

| Visitatierapport Vestia | Housing policy | n.a. | Evaluation | n.a. | 2021 |

| Visitatierapport Havensteder | Housing policy | n.a. | Evaluation | n.a. | 2023 |

| Visitatierapport Woonstad Rotterdam | Housing policy | n.a. | Evaluation | n.a. | 2018 |

[i] Note: For links to these publicly available documents, see the supplemental data online.

Second, communities of meaning should be identified that are relevant to the policy. In this article, the relevant communities of meaning are clear, as they are defined through law and local policy implementation: the municipality, housing corporations and tenant organisations.

Third, the discursive, specific meanings of policy artefacts should be identified. The discursive meaning of concepts in policy artefacts is studied using thematic content analysis (Waller et al. 2016). This methodology can identify intentions, focus and communication trends over time. The policy artefacts in Table 1 have been coded for themes that arose from previous research on social mix, demolition and circularity in construction. Analysis of policy demands close reading and a holistic understanding of the field and its actors to understand the social meaning of these themes. This means:

[to] identify the elements in argumentative interactions that are essential to explaining the emergence and persistence of particular discursive constructions.

In this case, it means identifying in what ways the Rotterdam housing policy has become embedded in a framing of social mix in city areas and what its practical implications are regarding the housing stock. Furthermore, policy metaphors are noted, as they summarise what the problem definition is.

Fourth, points of conflicts should be identified regarding the interpretation of meaning. These could be found in newspaper publications and a report by the Rotterdam Court of Auditors (Rekenkamer Rotterdam 2021). Finding discourses requires understanding the institutional design of policies and the discursive practices surrounding the policy. This justifies a relatively broad description of current policies beyond Rotterdam’s housing policy, as these belong to the relevant policy environment (Hoppe 2011: 139–140; Yanow 2000).

2.3 Data

The primary textual sources (‘policy artefacts’) of Rotterdam’s housing policy environment are listed in Table 1. These are municipal and national policy documents (which have a basis in law and/or municipal decision-making), policy agreements (municipal documents) and agreements (‘covenants’). These policy artefacts draw on other policy texts and transform these (Fischer 2003: 38).

This study also employs a small number of expert interviews. These interviews provided a background to the performance agreements in housing policy and the historical development of its topics. The respondents are from the Rotterdam municipality (three) and the Rotterdam housing corporations (two). The municipal respondents are senior civil servants with a central role in either the processes around the performance agreements or the Rotterdam circular economy policies. The respondents from the housing corporations represent two of the ‘big four’; requests with others were not met. Table 2 shows core data for the big four.

Table 2

The ‘big four’ housing corporations.

| NAME | APPROXIMATE HOUSING STOCK | ACTIVE AREA |

|---|---|---|

| Woonstad Rotterdam | 55,800 | Rotterdam |

| Woonbron | 25,570 | Wider Rotterdam region |

| Havensteder | 45,000 | Rotterdam area |

| Vestia | 29,000 | Rotterdam |

Interview topics centred on reflection of the role of performance agreements, the concept of circularity and how it is understood in Rotterdam. Additionally, circular deconstruction and criteria for deconstruction/demolition were discussed. Topics such as a construction material hub, the role of demolition companies and the broader policy environment were also recurrent themes.

This article concentrates on the period 2018–22. The starting point of 2018 is justified because from that date Rotterdam has had a circular economy policy that focuses on construction. Furthermore, in 2018, the national Concrete Agreement was signed, and the Transition Agenda Circular Construction started. This study refers to some earlier policies—notably the National Programme Rotterdam-Zuid (NPRZ) which started in 2010 and the first Rotterdam Housing Vision 2030 of 2016. These are included because they show that the social mix approach in Rotterdam housing policy is firmly entrenched.

The focus of this article—demolition in the context of social mix—leads to a limitation to two specific policy metaphors and how they interact: ‘Balanced Neighbourhoods’ (Wijken in Balans) and ‘Circular Rotterdam’ (Rotterdam Circulair). Rotterdam’s policy goals are clearly reflected in the names of its policies.

3. Policy context of performance agreements

Understanding the discourses around the demolition of social housing requires a description of the institutional setting of Rotterdam housing policy, which derives from national law. There are other policies and agreements too that are the result of negotiation processes rather than policymaking processes.

3.1 Dutch housing act (Woningwet 2015)

The primary aim of the Housing Act is to anchor the core task of the housing corporations: providing sufficient and affordable housing, the ‘societal task’ of housing corporations. The importance of the Act is that it provides the legal context for the relation between local government and the housing corporations.

The renewed Housing Act of 2015 requires that municipalities have a Housing Vision (Woonvisie) which is executed using the performance agreement instrument (Ministerie van BZK 2023). Rotterdam’s original 2016 Woonvisie was revised in 2019 (Woonvisie 2016, 2019). The housing vision includes the quantity and quality of housing, locations, spread of housing, attention for specific groups and the role of housing corporations. The national Housing Policy Priorities (Volkshuisvestelijke prioriteiten) must be included in the housing vision insofar there is a national relevance. Housing corporations must contribute ‘in a reasonable way’ to the execution of the municipal housing vision. This section of the Housing Act also introduces the process and actors of the performance agreements: the municipality, housing corporations and tenant organisations. The housing corporations also contribute to formulate the municipal housing vision.

3.2 Process and content of the performance agreement

The municipal housing vision is executed using the performance agreements. These are non-binding covenants in the sense that the municipality does not have ways to enforce them. The performance agreements are seen as ‘morally binding’ (respondent 1, civil servant).

The housing corporations are agenda-setters because they initiate negotiations about the performance agreements. They provide the municipality with their planned (de)construction activities. The municipality gathers data on the financial capabilities of the housing corporations, after which they must provide more detailed plans and the negotiated content of the performance agreement.

3.3 Other relevant policies

In addition to the Housing Act of 2015, the municipal housing vision and the performance agreement urban (de)construction in Rotterdam are also influenced by policies and agreements related to the broader Dutch climate policy. It is recognised that the construction sector is a major source of waste and emissions (Rotterdam Circulair 2021). Rotterdam has explicitly included concrete as a focus point in its circular and construction policy. This focus has a background in agreements between public and private stakeholders (van Langen & Passaro 2021). Most relevant here is the Green Deal on making the concrete supply chain more sustainable (Green Deal Verduurzaming Betonketen 2018). The aim of this Green Deal is to produce a strategy for the concrete sector on socially sustainable entrepreneurship and establishing a platform for the promotion of sustainable concrete production.

This Green Deal resulted in the so-called Concrete Agreement (Betonakkoord 2018). The Concrete Agreement has four main themes: CO2 reduction, circular economy, innovation and education, and natural capital. The signatories to this agreement commit to these sustainability and emission goals for 2030. This agreement can be seen as highly significant for the development of the circular economy in construction because it is signed by the Dutch government, local governments and most of the big players in the construction sector. Since 2019, Rotterdam is also a signatory (Rotterdam Circulair 2019). Circularity in Rotterdam is also rooted in other policies, such as the City’s Environmental Vision (Omgevingsvisie Rotterdam), which is based on the Dutch environmental law (Omgevingswet 2012). It contains a vision for a ‘circular city’, which is necessary due to CO2 emissions and raw material use. It stresses the reuse of materials and reduction of embodied carbon.

4. Findings: demolition discourses

An analysis of the documents in Table 1 using thematic content analysis results in a main identifiable discourse, two conflicts visible alongside it and one emerging discourse. The dominant discourse originates from Rotterdam housing policy, based on the municipality’s policy artefacts. The emerging discourse on circularity in construction is found in policy documents outside housing policy and recent performance agreements.

4.1 Discourse 1: the social mix in Rotterdam housing policy

Tieskens & Musterd (2013: 194–196) show that, historically, Dutch social mix policies have morphed into a metaphor for ‘solving urban problems’. Apart from physical interventions (renovations, demolition), social mix policies have aimed to diversify the social and ethnic composition of neighbourhoods by either displacement of the ‘original’ inhabitants or the influx of middle class ‘social risers’. The main idea is that isolated disadvantaged communities would benefit from mixing with groups from broader society to improve their social outcomes in terms of employment, education and reduction of social problems (Levin et al. 2014). In Rotterdam housing policy, the ideology of social mixing is seen in nearly every policy document. This must be seen as the dominant discourse, which is entrenched in core tenets of the housing policy.

This discourse is very visible in the multilevel governance of the National Plan Rotterdam Zuid (Midterm NPRZ 2022). This specific policy aims to improve the neighbourhoods of Rotterdam Zuid, which is included as an integral part of the performance agreements. It argues that bad housing influences many other outcomes, from educational attainment to social cohesion. The proposed solutions are from the social mix playbook: improving the quality of obsolete housing, increasing the supply of mid- and high-price housing through new construction and transformation of the existing stock, and managing the influx of new tenants by focusing of social risers and more diversity through specific development strategies for Rotterdam Zuid (Midterm NPRZ 2022: 17). For example, differentiation should be accomplished by ‘making more space for mid-price rental housing and home ownership’ because there are shortages of these of this category of housing (Midterm NPRZ 2022: 47). This is an example of the mobility aspect of social mix, which would remedy the concentration of urban poverty (Tieskens & Musterd 2013).

This discourse is clearly visible elsewhere in the Rotterdam housing policy, too. Woonvisie (2016: 17) states:

Creating attractive housing and living environments improves the quality of living and life in neighbourhoods. This way, we entice the socially upwardly mobile residents of Rotterdam South to stay here and attract new residents. […] All this contributes to strengthening social networks and social cohesion […].

Woonvisie (2019: 3) states:

By focusing on the middle and upper segments, we do not only solve a bottleneck for the households falling behind in those segments. It also creates room for a broader group of house seekers […] upwardly mobile people in the social segment can move on to the middle segment.

The core tenets of this discourse in housing policy are ‘balanced neighbourhoods’ and ‘housing stock imbalance’. Neighbourhood balance is arguably the central policy metaphor in Rotterdam housing policy, as it appears to be measurable. Neighbourhood disbalance is clearly defined: ‘A disbalance occurs when the social housing stock in a neighbourhood is 60% or greater of total stock’ (Gebiedsatlas 2.0 2020: 6). The Area Atlas shows the areas of Rotterdam in which disbalance occurs and what the situation is projected to be in 2030. The section describing the task ahead for the social housing sector states:

In a good number of neighbourhoods, growth of the social segment is not desirable. On balance, the market share of the social segment will not increase. Then it is important that, in addition to new construction in these neighbourhood, social stock should also be developed to higher segments.

Both versions of the Woonvisie 2030 discuss the imbalance in terms not only of neighbourhoods but also of the total housing stock. Woonvisie 2030 (Woonvisie 2016: 70) states regarding the imbalance in the housing stock:

Rotterdam is the only municipality with a large excess of low-cost housing. This makes our housing market fundamentally different and is the reason why increasing the share of medium/high price has been a policy commitment for years.

The policy goal is that the housing stock must change for two reasons: a housing shortage in the mid-price segment (or housing oversupply in the social segment); and the assumed positive effect of social mixing. These two policy arguments can be evaluated.

The main solution for achieving a better balance in the housing stock or a reduction in the oversupply of social housing is demolition (Woonvisie 2016: 16, 65). In practical terms, the need for demolition is expressed starkly:

On balance, the reduction of the low-cost stock through demolition at the urban level is at least 10,000 dwellings.

(Woonvisie 2016: 16; see also Woonvisie 2019: 7)

The demolition of social housing is therefore firmly entrenched in Rotterdam’s core housing policy documents (see also Musterd & Ostendorf 2008).

4.1.1 The dominant discourse in the performance agreements

The performance agreements are the primary policy instrument the municipality has for its social housing policy, as framed by national laws. The preamble to these agreements notes the polices that are relevant for the policy context of the performance agreements. The dominant discourse (social mix through demolition) is implicitly included in the performance agreements through these policy documents. The Rotterdam Housing Vision is central, but also policy documents such as the NPRZ, the Area Atlas and BOK (2019). The BOK is referred to often in the sections related to development of the housing stock of all performance agreements after 2019. It is a somewhat controversial agreement between the big four housing corporations and the municipality. It consolidates the need to reduce social housing stock in exchange for new construction locations. The housing corporations commit to large-scale urban restructuring, but because in that process they also give up locations in which they may not be able to provide social housing, they negotiated a compensation in the form of preappointed construction locations. The BOK, therefore, implicitly acknowledges a tension in social housing policy mentioned below: the role of the financial space of housing corporations. The performance agreements can be seen as coordination mechanisms that guide the (de)construction of social housing in the broader policy context.

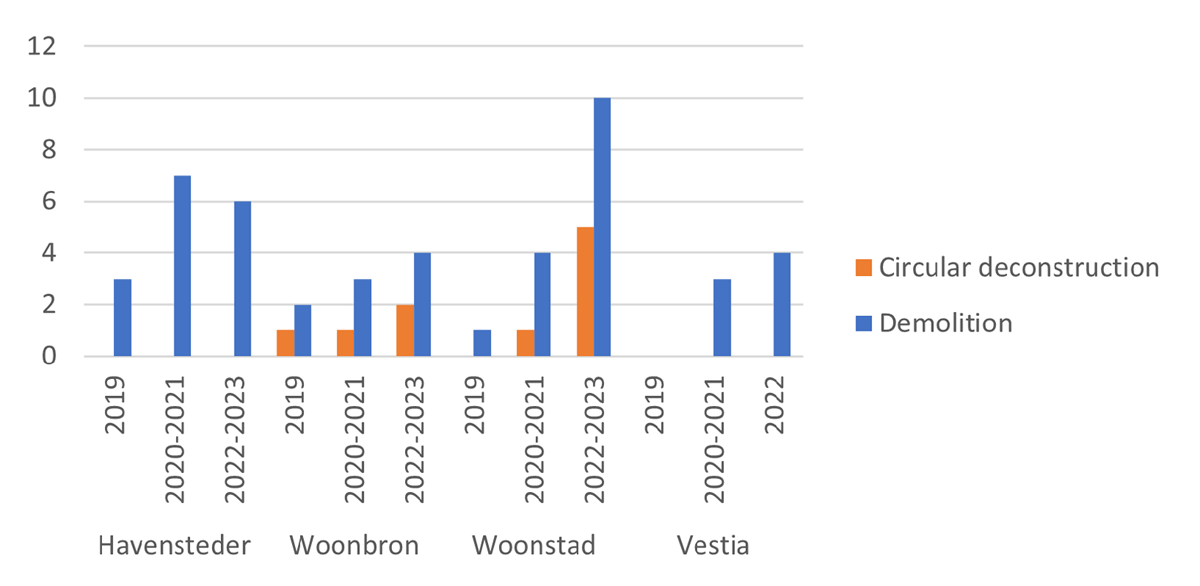

Figure 1 shows how often demolition is mentioned in the performance agreements, including circular demolition. The performance agreements are a non-binding consolidation of (de)construction plans, which means they are not very specific unless projects are ‘shovel-ready’. Table 3 shows the actual number of demolished buildings in Rotterdam. This level is higher than what is indicated in the performance agreements, but lower than in the Housing Vision 2030. One expert from the municipality mentioned that this lower level may be related to the social context of demolition plans and other potential delays.

Figure 1

Mentions of ‘deconstruction’ in performance agreements.

4.2 Challenges to dominant discourse: local resistance against demolition

Rotterdam’s official housing policy, its instruments and priorities are clear. Nonetheless, it is possible to discern a challenge to the dominant discourse. Several actors dispute the interpretation of the facts of the housing market situation in Rotterdam and criticised the focus on reducing the social housing stock. Yanow (2000) shows that this kind of conflict is important to understand the social meaning of policy. In this challenge, the essence of the municipal policy narrative is disputed: rather than a social housing oversupply, the actors in this discourse argue that there has been a steadily increasing pressure on the social segment of the Rotterdam housing market, which municipal policy has made worse by focusing on the demolition of social housing and replacing it with higher price housing. This challenge is visible occasionally in the news media (NOS 2021; Ridderkerks Dagblad 2021), but also in a critical report by the Rotterdam Court of Auditors (Rekenkamer Rotterdam 2021). This challenge is consistent with what Deboulet & Abram (2017) found for France and the UK.

The contentious issue is clearly seen in a statement by the Rotterdam network of tenant organisations (Gezamenlijke Overleg Huurdersorganisaties Rotterdam—GOH) in which it explains why the tenant organisations did not sign the performance agreements in 2021:

The main reason for not signing is that the municipality of Rotterdam remains committed to making [the] social housing stock decrease.

(GOH 2021)

In 2019 the housing corporations also expressed a concern about the shrinking social housing segment to the municipality.

The Rotterdam Court of Auditors highlights the mismatch between supply and demand in the social housing stock. It found that the municipality used imprecise methodologies and ‘soft’ data to establish the size and composition of the housing market stock (Rekenkamer Rotterdam 2021: 134). It argues that housing market data point to the increasing pressure of the Rotterdam social housing market, and a goal of demolition of 10,900 social housing units was not well-founded or warranted given the available data. The Court of Auditors argues this increasing pressure is partly due to the demolition of ‘oversupply’ of social housing (Rekenkamer Rotterdam 2021: 113–131).

In conclusion, the Court of Auditors states that the municipality could not reliably ascertain what was the true state of the social housing market (Rekenkamer Rotterdam 2021: 13). Based on the municipality’s calculations, the problem of the local housing market was defined as the ‘oversupply of social housing’. The broader housing policy was based on this fact and the performance agreements are used to implement these policy choices.

In this context, the Court of Auditors draws attention to the limited participation possibilities in policymaking for tenants. Institutionally, tenants (and citizens) have direct participation possibilities only in the context of the performance agreements and through municipal elections. As Hoppe (2011: 216) states:

Political participation is allowed in the choice among a politically limited set of alternatives for problem solutions. However, the problem itself has been defined already and policy-making officials and other experts fix the alternatives.

Participation largely becomes supporting a certain policy alternative. Table 4 shows that the tenant organisations have not signed the performance agreements in many years. This is a clear sign of protest in the institutional setting. The Court of Auditors (Rekenkamer Rotterdam 2021: 25) further notes that tenants do not have sufficient rights to participate in decisions that affect them and that there are not sufficient information channels between tenants/tenant organisations and the municipality through which participation could have been enhanced. The state has instructed that the performance agreement is legally valid despite the refusal of tenant organisations to sign.

Table 4

Performance agreements (prestatieafspraken) agreed or not signed by year and housing corporation.

| YEAR OF … | WOONBRON | WOONSTAD ROTTERDAM | HAVENSTEDER | VESTIAa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 2020–2021 | √ | × | × | √ |

| 2022–2023 | × | × | × | × |

[i] Note: aVestia only signed a performance agreement for 2022, because it would be split up into separate entities from 2023.

√ = Signed (approved), × = not signed (not approved).

Source: Rekenkamer Rotterdam (2021: 160–161).

The challenge of the dominant discourse by the Court of Auditors’ report and the refusal to sign performance agreements is primarily rooted in the contestation of facts about the housing market stock and how the municipality has acted on these facts. Furthermore, it is an indication of the weak voice tenants have in housing policy that especially concerns them.

4.3 A second challenge: housing corporations’ financial position

A potential conflict connected to the dominant discourse highlights the tensions inherent in the task of providing social housing. Social housing policy depends on the ability of the housing corporations to contribute to the development of the housing stock: housing corporations must make sensible investments. Woonvisie (2019) notes that the housing corporations will provide 80% of new social housing (8400 houses). This is a potentially difficult task, following debt overhang and housing corporation restructuring after the financial crisis of the 2010s. The Housing Act of 2015 focuses more on monitoring of the financial circumstances of housing corporations for this reason. One instrument was the landlord levy (verhuurdersheffing). This tax was introduced in 2013 (but abolished from 2023) to reduce the financial space of housing corporations to prevent overly risky investment behaviour.

This potential conflict in housing policy is less visible than the previous one because it relates in part to the general state of the economy. In the Dutch context, there are semi-regular evaluations of the social housing corporations relating to transparency. In Rotterdam, the following corporations have been recently evaluated: Vestia (Maatschappelijke Visitatie Vestia 2017–2020; Visitatierapport Vestia 2021), Havensteder (Maatschappelijke Visitatie Havensteder 2018–2021; Visitatierapport Havensteder 2023) and Woonstad Rotterdam (Maatschappelijke Visitatie 2018–2021; Visitatierapport Woonstad Rotterdam 2023). These reports also reiterate the problem of participation.

These reports evaluate the ‘societal task’ of the housing corporations. The financial space of the housing corporation is central for their daily management, investments and renovations. The evaluation committee is very positive about Woonstad Rotterdam, as it has a good financial position. Havensteder, on the other hand, has a high financial risk profile because its housing stock is relatively old with high maintenance costs. Havensteder has a potentially pressing debt situation. The report explicitly mentions that the Housing Vision 2030 is not positive for Havensteder’s housing stock value. Vestia is in many ways an anomaly because it is heavily burdened by debt and ceased to be an independent entity from 2023. During the most recent evaluation period, it was in receivership. These evaluations show the impact of the corporations’ financial positions on their potential to provide social housing. The financial position of housing corporations could be a pressing theme in the near term due to rising interest rates and construction material costs. The social housing rent level is fixed, and in municipal tenders the price of a plot of land for social housing is fixed. This means that for new construction the total budget is tight, and housing corporations may struggle to provide social housing within that financial framework.

The challenge is that the financial situation of housing corporations does not necessarily match the ambitions of Housing Vision 2030. The Rotterdam Court of Auditors (Rekenkamer Rotterdam 2021) reports that according to the municipality, the ambition of the housing corporations in performance agreements is rather modest, which could be explained by their financial situation and risk management. This explains the significance of BOK (2019): losing ‘market share’ at the neighbourhood level is the policy aim also accepted by the corporations, but they carry a significant financial risk. The evaluation reports indicate that for the most part, the housing corporations have been able to provide sufficient social housing. The Havensteder evaluation states the housing corporation finds itself in a split between balancing housing stock (dominant discourse) and the demand for more social housing (challenge 1). The financial challenge of providing social housing therefore exhibits a tension between municipal goals and corporation possibilities.

4.4 Emerging discourse: circularity in construction/demolition

From 2018 onwards, at the national and municipal level, circularity has become an emerging aspect of urban policy. In Rotterdam, circularity is limited to four key sectors: healthcare (primarily wastewater recycling), waste streams (increasing reuse of biowaste), consumption goods (re- and upcycling) and construction. In Rotterdam Circulair (2019) circularity in the construction sector is focused on material passports for buildings, building material hubs, a digital marketplace for reusable building materials and membership in the Dutch Concrete Agreement of 2018. Respondent 2 mentions that starting a circular economy policy is a long-term project in terms of the municipal organisational capacity, which also is reflected in the emergence of circular thinking in housing corporations (respondent 5). In the Rotterdam case, the urgency of the policy goal is made tangible by referring to 2030 as being ‘two council periods away’.

This discourse is currently connected to housing policy on the level of ideas. Rotterdam Circulair (2019: 16–17) reports that during the council period 2018–22, 18,000 new houses will be built, which is connected to the potential of circularity. In a conceptual sense, the Rotterdam circular strategy is mostly based on a consultancy report by Metabolic (2018: 70–71) on the material flows of Rotterdam construction. This report is the basis of thinking about circularity in Rotterdam. It is connected to issues of demolition in that it mentions the material flows of construction, renovation and demolition. The report notes that in theory this material flow could result in a large amount of secondary building materials, but it does not see this as realistic because the market for filler material is assumed to be saturated (Metabolic 2018: 72; Transitieagenda (2018: 15). Glass, wood, metals and plastics are demolition waste that can potentially be recycled. Mixed wasted can be used for energy production. Debris, originating from concrete and stone, can only be downcycled according to this report. Downcycling often means use as filler under roads. The amounts calculated in the report are based on demolitions in 2015.

The main message of this report is that it is necessary to prevent demolition, but also to maximise the value of demolition material. The report presents a few recommendations towards the latter: increasing the value of recyclable material and studying the characteristics of demolition waste for potential reuse. The latter could affect both tendering processes and structural–technical processes.

Metabolic (2018) is included as the basis of Rotterdam’s circular policy. This inserts a new tension in the city’s urban renewal plans by focusing on the environmental burden of the construction sector, through material flows, inherent in urban construction. On the one hand, it sees circularity of demolition waste (e.g. concrete) in preventing demolition in the first place, consistent with ‘refuse and rethink’ of the R-ladder. Note: R-ladder is a hierarchical listing of strategies that can be used to measure the circularity of a product or material, ranging from ‘recover’ to ‘refuse and reduce’. Generally, the higher up the R-ladder is a strategy, the more circular it is (Zhang et al. 2022). On the other hand, it argues that demolition waste should be upcycled. In other words, revaluing demolition waste, through circular demolition, could become a source of income. Metabolic (2021) translates this to a selection of recyclable and reusable products of the ‘urban mine of Rotterdam’.

Metabolic (2021: 8) connects circularity to the existing social mix and urban renewal policies for Rotterdam. It uses a so-called ‘historical BIM-model (Building Information Modeling)’ to estimate the material content of planned transformation, renovation and demolition until 2030. This models also enables estimation of the reusability of materials, their value and environmental impact. For future reuse, this is therefore extremely valuable. To ‘exploit’ the Rotterdam urban mine, circular demolition/deconstruction is needed.

Circular demolition is an emerging theme in the performance agreements. As Figure 1 shows, two of the four housing corporations mention circular demolition in these documents. In a situation with rising costs for construction materials it is possible that reusing materials would be cost-effective, but as a Woonstad pilot showed (toilets from a demolished hospital; Rotterdam Circulair 2019: 23) it is then necessary to integrate maintenance in daily practice in a new way. A similar point was made by the circular economy expert of the municipality: diversity in materials may lead to more complicated maintenance procedures, as a wider variety of knowledge about components is needed. A more complex management of maintenance also could lead to higher costs.

Revaluation of building materials is a fully new and emerging theme inside the housing corporations, which should be the topic of further research. For example, current valuation of concrete as (natural) capital is difficult: if a building material is part of the building it does not have a separate value. However, because it is the most voluminous material in demolitions and in connection with material passports and circular tendering demands, it may be necessary to find ways to valuate these materials. Circular demolition adds tension to the demolition plans of the city of Rotterdam because it adds a new variable: the value of demolition waste for reuse. This can be contractually resolved.

In aiming for circular demolition, a new light is cast on the second challenge to social housing production. The capital position of housing corporations may change if their material capital is revalued—not building waste but building material. It is not clear if and how this would happen, but rules about the environmental performance of buildings in the Netherlands could provide an impulse to the reuse of building materials (see also Francart et al. 2019). On the other hand, it is a matter of negotiation of deconstruction contracts whether this renewed value will stay with the housing corporations or go to deconstruction companies. A new political issue could be where to apply the reused building material.

In the performance agreements, the issue of circularity is still minor, although two of the housing corporations appear to have taken circularity much further than circular demolition. This emerging discourse is based on European and national climate agreements. It approaches the construction sector from its impact on emissions rather than from a housing market perspective.

5. Discussion

The two discourses discerned in the Rotterdam housing and circular economy policy documents represent the situation until now. The Housing Vision 2030 will be updated by the end of 2023 and more detailed implementation plans for the circular construction policy are being made following the most recent municipal elections. It is possible that some of the tensions between the discourses will be resolved with new policy. It remains to be seen what impact the European Central Banks’s (ECB) interest rate decisions will have on the financial position of the housing corporations.

Tieskens & Musterd (2013) discussed social mix policies and the effect on the displacement of the original inhabitants of neighbourhoods. The present article has not reflected on that aspect of social mix policies, but a challenge to the dominant discourse is clearly visible. The idea of Rotterdam’s Balanced Neighbourhoods policy is to reduce the dominance of social housing in certain neighbourhoods. This implies that either through demolition, renovation or rebuilding, there will eventually be less housing space for those entitled to social housing. In this sense, social mix policies are firmly entrenched in Rotterdam, with relatively little participation possibilities.

This does not have to be a problem. The evaluation reports of Havensteder and Woonstad Rotterdam state these housing corporations have improved their inclusion of tenants and neighbourhood civil society organisations in (de)construction projects. Even though the municipality does not provide an official route for participation beyond the performance agreements, the housing corporations may be able to fill that void to some extent. Housing corporations could have enough common ground with tenants to ‘move together’. This can be observed in the first challenge to the dominant discourse: corporations and tenant organisations exhibited a shared view of the housing market situation. Deboulet & Abram (2017) nonetheless show that participation can easily become a top-down formality. The Rotterdam Court of Auditors (Rekenkamer Rotterdam 2021) states that the performance agreement process is quite burdensome on the tenant organisations. Development of real tenant participation therefore requires support from the municipality as well (in the form of expertise). The municipality already provides expertise to the housing corporations on energy transition and circularity already. This could be extended to the tenant organisations.

The big question is whether and how tension will develop on the issue of circular deconstruction. Metabolic (2021) is quite literal about the location of Rotterdam’s urban mine: the same demolition projects that are planned in connection with the Balanced Neighbourhoods policy. It appears Rotterdam’s circularity would be founded on deconstruction of social housing. Actual demolition rates are far from what is planned (Table 3), which would imply Rotterdam would have to accelerate urban renewal to achieve the material volumes envisioned in Metabolic (2021). Given existing disputes about housing market imbalance as well as a wealth of studies on why social mix policies fail, it is doubtful whether this view of ‘internal circularity’ can proceed very far. It remains to be seen to what extent the municipality will emphasise its current Balanced Neighbourhoods policy as a way to have access to the material resources for the emission reductions to which it is committed.

A potential political conflict over the use of scarce and expensive building materials could emerge. The combination of the dominant and emerging discourse begs the question: Is it intentional that social housing should provide the (envisioned) majority of building materials for higher income housing? There is a possibility that this could turn into a class issue, with deleterious effects for the social support of circularity.

This article focuses on the emergence of circularity in housing policy. This is already the ‘next phase’ in local climate policy, as an earlier policy focus has been on the energy transition in the Netherlands. The Dutch energy transition intends to transform housing’s energy needs and sources. This involves the energy label of houses, but also structural change (new energy sources for space heating). These issues have been included in the earlier performance agreements and the Housing Vision 2030 (Woonvisie 2016). The energy transition processes are not finished and it is possible that issues with a direct impact on the tenants’ budget have priority over circular policies, also for tenants.

6. Conclusions

In this analysis of Rotterdam’s housing policy, a dominant discourse was found around the theme of ‘balancing neighbourhoods’ to create a desired social mix. This policy goal is entrenched in many municipal policies related to the housing market and social housing. The municipality’s goal is to restructure many of Rotterdam’s old neighbourhoods to contain less social housing and more mid- and high-price housing. The stated grounds for this policy range from technical obsolescence and neighbourhood liveability and city attractiveness to solving social–economic problems, which is typical of social mix policy. A technical reason for the need to demolish social housing was given in a presumed oversupply of social housing. This reason was challenged by housing corporations, tenants and the Rotterdam Court of Auditors. They argue that pressure on the social housing market has increased and demolition of social housing has made this problem worse. The Court of Auditors has argued that the municipality has employed a vague problem definition and ‘soft’ data, resulting in unreliable calculations. Another challenge to the main discourse is the organisational relationship between municipality and housing corporations. The financial capabilities of housing corporations to fulfil their societal tasks as defined in the performance agreements is a potential hurdle to social housing provision. Due to legacy financial issues, and also the current pressure of building material costs and interest rates, housing corporations may struggle to deal with the tasks given to them through municipal housing policy.

An emerging discourse revolves around circularity in Rotterdam policy. Circular economy in the construction sector is a clear focus for Rotterdam, but the housing corporations and the municipality’s experts see challenges in costs (e.g. maintenance, role of demolition companies) and benefits (how to measure the value of potential future building materials). The biggest challenge this emerging discourse poses is nonetheless political. The consultancy reports explicitly included in Rotterdam’s circular economy policy base the size and material composition of Rotterdam’s ‘urban mine’ on planned demolition and transformation of (mostly) social housing. This connection between circular economy policy and social housing policy should be openly discussed in local politics. For the municipality there is the risk that circular economy policies are perceived to be for the better-off at the expense of those who are dependent on the availability of social housing (due to employment status, income level or socially disadvantaged background).

Cities such as Rotterdam, with a sizable, relatively old social housing stock, likely can benefit from circular (de)construction. Other than the technical challenges, a great deal of thought should go into the politics of the use of harvested material, especially if the source is social housing. Future research could focus on this aspect, as it is likely to be important for the social acceptability of circularity in construction. The issue of the valuation of demolition waste/harvested building materials takes this topic in the direction of political economy, as actors have to rethink and renegotiate processes and contracts. Also tendering criteria and tax issues must be reconsidered in the light of new valuations.

In the Netherlands and other parts of Europe the demolition of social housing has taken place as an intervention to engender a better social mix. The inclusion of circular construction as an argument for demolition/deconstruction of social housing has the potential to make demolition an even greater local political issue. For policymaking purposes, being aware of the interests of stakeholders and the political ramification of demolition is a necessary first step.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the two anonymous referees and the editor for their constructive comments which improved this article. Also thanks to Tommi Halonen for inspiring discussions about an earlier draft of this article.

Competing interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Data availability

For the documents studied, see the supplemental data online. Interview transcripts are not available.

Ethical approval

Interview data were obtained with informed consent in accordance with the ReCreate Research on Humans ethical protocol.

Funding

This research was funded by the ReCreate project from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program (grant agreement number 958200).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.305.s1