Introduction

Forty years after the emergence of AIDS, 1.3 million people globally became newly infected with HIV in 2022 [1]. Advances in awareness, prevention, and medical treatments over the decades have allowed many in the developed world to view AIDS as a survivable, “chronic disease,” yet barriers continue to fuel new infections and deaths, especially among marginalized populations [2–4]. Worldwide, key groups, including men who have sex with men and bisexual men, transgender people, sex workers, and people who inject drugs, remain disproportionately burdened by HIV, facing infection rates dozens of times higher than the general population [5–9]. This trend is particularly evident in high- and middle-income countries outside of Africa, where these key populations account for the majority of new infections [10]. In contrast, the HIV epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is primarily driven by transmission among young women and adolescents. While key populations accounted for 25% of new HIV infections in SSA in 2022, they represented 80% of new infections in the rest of the world [9]. This is likely due to the generalized nature of the epidemic in SSA, where HIV is spread through heterosexual sex in the general population. Nevertheless, within SSA, key populations still experience disproportionately high HIV burdens [10].

Behind what some public health experts have deemed a “hidden HIV epidemic” among vulnerable groups [11], stigma and discrimination create immense, complex barriers, preventing further control of the disease [12]. Where ignorance and injustice collide, misplaced fear or condemnation of those living with HIV persists. This stacks the cards decisively against many already facing profound challenges like homelessness, lack of healthcare access, poverty, and oppression [13, 14]. When key populations fear scorn, judgment, or reprisal for revealing their status or seeking necessary care, virus transmission marches on. Structural violence becomes embodied violence, which highlights the tangible, bodily impact of violence, emphasizing that its effects are not only psychological or social but also deeply physical [15, 16]. Yet promising programs challenging assumptions and bringing compassionate care directly to affected groups offer hope in curtailing new infections at last [17].

To finally end AIDS as an epidemic by 2030 as targeted, HIV response strategies must continue evolving to meet the marginalized where they are, to see humanity within health inequities, and to link all lives worth saving to the care required to save them [18]. This paper offers an overview of cases of stigma, policy proposals, and stakeholder calls-to-action, focusing on the imperative to confront stigma to reach and assist key groups where needs remain greatest. A future free of AIDS depends on science guided by social conscience, policies informed by those they fail to currently protect, local engagement embracing humanity’s shared condition, and care distributed equitably to those it remains beyond reach.

Defining HIV/AIDS-Related Stigma

Stigma is a complex social process involving labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination, resulting in a powerful discrediting of an individual or group [19]. In the context of HIV/AIDS, stigma refers to the negative attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors toward people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) or those perceived to be at risk of HIV infection [20]. HIV/AIDS-related stigma can be defined as the prejudice, discounting, discrediting, and discrimination directed at people perceived to have HIV/AIDS, as well as their partners, friends, families, and communities [21]. It manifests in various forms, including instrumental stigma, a reflection of the fear and apprehension that HIV/AIDS is contagious and potentially life-threatening; symbolic stigma, the perception that HIV/AIDS is associated with behaviors that are considered deviant or morally reprehensible, such as homosexuality, drug use, or promiscuity; and courtesy stigma, the stigmatization of individuals related to PLWHA, such as their families, friends, and healthcare providers [21, 22].

HIV stigma perpetuates and reinforces social inequalities, especially those related to class, race, gender, and sexuality [23]. Extensive evidence shows that this social phenomenon negatively affects the health of individuals living with HIV [24].

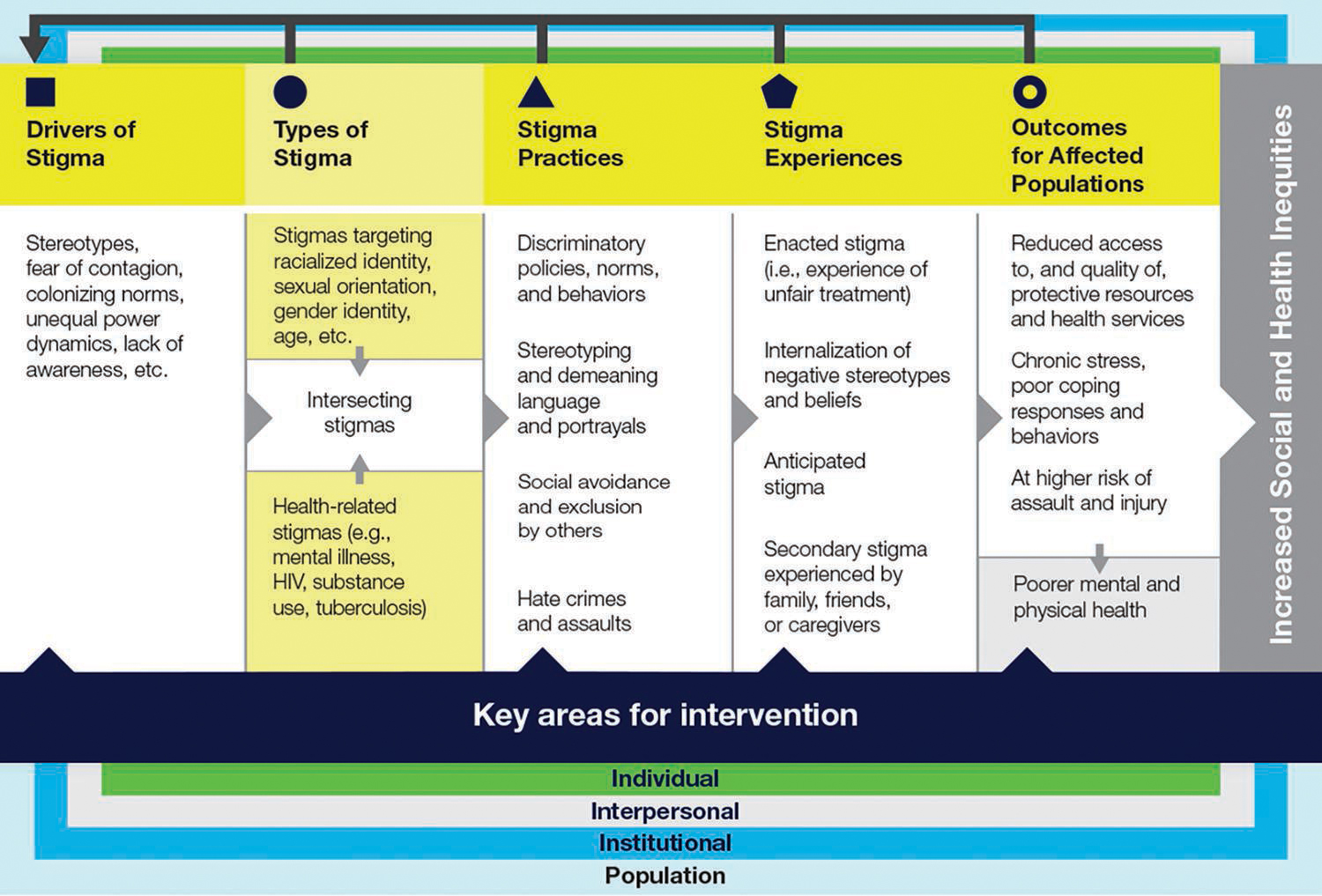

Theoretical Model Explaining the Impact of Stigma on HIV/AIDS Prevention, Care, and Treatment

The HIV Stigma Framework developed by Earnshaw and Kalichman [25] provides a comprehensive understanding of how stigma operates at multiple levels and impacts various aspects of the HIV/AIDS response. This framework outlines three main mechanisms through which HIV stigma affects key outcomes: enacted stigma, anticipated stigma, and internalized stigma.

Enacted stigma, which refers to overt acts of discrimination or violence against people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) or those perceived to be at risk, can create a climate of fear and secrecy, discouraging individuals from seeking HIV testing, disclosing their status, or accessing prevention, care, and treatment services [26]. At the interpersonal level, enacted stigma from family members, partners, or peers can disrupt social support networks essential for coping and treatment adherence [27].

Anticipated stigma, or the expectation of experiencing stigma and discrimination, can deter individuals from engaging in preventive behaviors, adhering to treatment regimens, or seeking social support [28]. At the individual level, this fear of stigma can hinder early diagnosis and timely interventions, ultimately undermining efforts to control the epidemic.

Internalized stigma, where PLWHA accept and internalize negative attitudes and beliefs about HIV/AIDS, can lead to low self-esteem, depression, and a sense of worthlessness [29]. This can undermine their motivation to engage in preventive behaviors, adhere to treatment regimens, or seek social support, negatively impacting their overall well-being and health outcomes.

Furthermore, the framework recognizes that HIV stigma operates at multiple socio-ecological levels, including individual, interpersonal, community, and structural/societal levels, and that these levels interact and influence one another [25]. At the community level, institutional stigma within healthcare settings, workplaces, or educational institutions can discourage PLWHA and those at risk from accessing services, jeopardizing their well-being and increasing the likelihood of transmitting the virus to others [30]. At the structural/societal level, stigmatizing laws and policies, as well as a lack of adequate resources, can perpetuate stigma and hinder the availability and accessibility of HIV/AIDS services, particularly in resource-limited settings [31].

Stigma Framework/Model

Source: Earnshaw and Kalichman (2013).

Practical Application of the Stigma Framework/Model to HIV/AIDS

Methods and Search Strategy

This narrative review aimed to synthesize existing literature on “The Fight for an AIDS-Free World: Confronting the Stigma, Reaching the Marginalized.” A comprehensive literature search was conducted across multiple academic databases, including PubMed, Medline, and CINAHL, using these keywords: “HIV stigma,” “AIDS stigma,” “HIV/AIDS marginalized populations,” “HIV prevention,” “HIV care,” “HIV treatment,” “social determinants of health and HIV,” “intersectionality and HIV stigma,” and “public health interventions for HIV.” The search strategy involved using a combination of keywords and Boolean operators to ensure a comprehensive retrieval of relevant studies. Inclusion criteria focused on peer-reviewed studies published in English that addressed HIV-related stigma and its impact on marginalized groups, while non-peer-reviewed articles and studies not focused on stigma were excluded. Data extraction involved collecting study details, key findings, interventions, and recommendations. A thematic synthesis approach was employed to identify and group key themes, including the nature and sources of HIV stigma, intersectionality, impact on marginalized populations, and effective interventions. While a formal quality assessment was not performed, a critical appraisal of each study’s methodological rigor and relevance to this review was considered. This narrative review was conducted using publicly available data from published studies. The standard requirements for ethical approval and informed consent are not directly applicable. However, ethical standards in reporting and synthesis were upheld by accurately representing study findings.

Statistics on Infections and Deaths among Key Groups

Despite global progress, stark disparities remain in the epidemic’s impact, with new analysis showing marginalized groups continuing to bear disproportionate infection rates and barriers to care [32–34]. According to the UNAIDS 2022 update, 650,000 deaths globally from AIDS-related illnesses were reported in 2021, highlighting the ongoing deadly toll where treatment lacks access [1]. Groups facing structural marginalization, such as men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender women, people who inject drugs (PWID), sex workers, and prisoners, continue to be impacted the hardest [35, 36].

In 2022, the risk of acquiring HIV was significantly higher for key populations compared to the wider global population. Specifically, PWID faced a 14 times higher risk, gay men and other men who have sex with men had a 23 times higher risk, sex workers had a 9 times higher risk, and transgender women had a 20 times higher risk [37]. Despite 40 years of the HIV pandemic, these key populations continue to be at a disproportionately high risk, which is unacceptable. The global median HIV prevalence among adults aged 15–49 in 2022 was 0.7% [1, 32], yet this prevalence was markedly higher among key populations: 2.5% among sex workers, 7.5% among gay men and other men who have sex with men, 5.0% among people who inject drugs, 10.3% among transgender persons, and 1.4% among people in prisons [1].

When comparing regional statistics (Table 1), Eastern and Southern Africa consistently exhibit the highest HIV prevalence among key populations. In this region, the general population’s estimated HIV prevalence is 5.9%, with key populations experiencing significantly higher rates. Sex workers in Eastern and Southern Africa have an HIV prevalence of 29.9%, the highest globally, while MSM have a prevalence of 12.9%. People who inject drugs in this region report a prevalence of 21.8%, and transgender people face the highest burden with an HIV prevalence of 42.8% [38]. In contrast, the general population in the Caribbean has an HIV prevalence of 1.2%, but the rates among key populations are also notably high. Transgender people in the Caribbean face an HIV prevalence of 39.4%, the second highest globally, while MSM have a prevalence of 11.8%, and sex workers have a prevalence of 2.6% [1, 38].

Table 1

Regional statistics on HIV prevalence among key populations compared with the general population.

| REGION | SEX WORKERS | GAY MEN AND OTHER MEN WHO HAVE SEX WITH MEN | TRANSGENDER PEOPLE | PEOPLE WHO INJECT DRUGS | PEOPLE IN PRISONS | THE GENERAL POPULATION |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia and the Pacific | 1.1% | 4.70% | 3.9% | 4.2% | 0.9% | 0.2% |

| Caribbean | 2.6% | 11.8% | 39.4% | 3.6% | 1.2% | |

| Eastern and southern Africa | 29.9% | 12.9% | 42.8% | 21.8% | 5.5% | 5.9% |

| Eastern Europe and central Asia | 2.0% | 4.3% | 1.7% | 7.2% | 1.1% | 1.2% |

| Latin America | 1.3% | 9.5% | 14.7% | 1.5% | 0.6% | 0.5% |

| Middle East and North Africa | 1.1% | 6.6% | 0.9% | 0.2% | 0.06% | |

| Western and central Africa | 7.5% | 8.0% | 21.9% | 3.7% | 2.8% | 1.1% |

| Western and central Europe and North America | 0.8% | 5.5% | 7.6% | 5.0% | 1.0% | 0.2% |

[i] Source: The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), 2023.

Asia and the Pacific report lower but still concerning HIV prevalence rates among key populations. The general population’s estimated prevalence is 0.2%, with sex workers at 1.1%, MSM at 4.7%, PWID at 4.2%, and transgender people at 3.9% [37]. Eastern Europe and Central Asia show an estimated HIV prevalence of 1.2% in the general population, with key populations like sex workers at 2.0%, MSM at 4.3%, PWID at 7.2%, and transgender people at 1.7%. This region also reports high prevalence rates among people who inject drugs, especially in certain areas [32]. Latin America, with a general population HIV prevalence of 0.5%, reports key population prevalence rates such as 1.3% among sex workers, 9.5% among MSM, 1.5% among PWID, and 14.7% among transgender people. The Middle East and North Africa region has a general population HIV prevalence of 0.06%, but key populations such as MSM and PWID report much higher rates of 6.6% and 0.9%, respectively. In Western and Central Africa, where the general population’s estimated HIV prevalence is 1.1%, key populations face significantly higher rates, with transgender people at 21.9%, MSM at 8.0%, and sex workers at 7.5% [38]. These regional differences underscore the diverse epidemiological profiles and necessitate tailored approaches in different contexts to effectively address the global HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Stigma Faced by Key Groups

Behind these statistics, societal stigma and continued criminalization in many nations fuel risk and create barriers across groups. Perceived stigma has direct links to adverse health outcomes, with experiences of discrimination significantly associated with gaps in treatment and care [12, 18]. For groups like PWID, stigma compounds the adverse health effects of issues like homelessness or incarceration [39]. Racial and ethnic minorities face concurrent stigma, with African Americans accounting for over 40% of new HIV diagnoses in the US [40]. In the US, gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) face high rates of infection alongside homophobia, creating barriers to care [41]. Transgender women, especially trans women of color, report extreme stigma including violence and discrimination, deterring care engagement [42].

A Pan-American Health Organization report cites cultural taboos around homosexuality and gender diversity alongside a lack of legal protections, enabling healthcare stigma and discrimination toward LGBT populations throughout Latin America and the Caribbean [43]. Similarly, sociocultural taboos and lack of sex education enable stigma across Asia-Pacific. Analyses cite the stigma facing key groups in accessing HIV services from Australia to Malaysia to China [44, 45].

Despite progressive policies in many areas, Europe has growing HIV rates among men who have sex with men amid stigma. A review found that 28% reported discrimination by healthcare workers and systemic stigma, driving risk environment [46]. Additionally, the historic early denial of HIV crisis focused on outsider groups such as gay and bisexual men now among the highest new infection rates in Africa [5]. Sex workers also face criminalization in many nations despite calls for reform from health bodies [47].

Furthermore, the lack of basic resources proves a major barrier to managing HIV or accessing preventative options [48]. In resource-rich nations like the US, factors such as poverty, homelessness, lack of insurance, and geographic distance from LGBTQ-inclusive care providers still impact outcome disparities [49]. Support services are vital yet often lacking for marginalized groups, exacerbating barriers [50].

National and Regional Programs Confronting Stigma Against Marginalized Groups

Grassroots outreach overcoming stigma

Peer involvement has shown immense promise in confronting stigma to reach vulnerable groups through understanding and assistance from those walking similar paths [51, 52]. Grassroots groups like the Latino Commission on AIDS directly engage Hispanic/Latinx communities facing cultural taboos regarding LGBTQ identities or HIV status, through community education and empowerment programs led by Latinx peer leaders [53]. Studies on peer navigation interventions emphasize their success linking stigmatized groups to testing, treatment, and support services [54]. Peers help overcome stigma-related mistrust of systems [55].

Policy initiatives against stigma

Global goals through frameworks like UNAIDS’ 90-90-90/ 95-95-95 targets have included specific aims to eliminate HIV/AIDS stigma alongside infection and death reduction targets [56–58]. Research cites anti-stigma initiatives as integral in supporting widespread testing, sustained treatment access, and preventing new transmissions – all cornerstones of epidemic control [59].

National HIV/AIDS strategies similarly recognize confronting bias as vital for health equity. Australia’s current strategy sees reducing stigma as essential to supporting the participation of marginalized groups like Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in care [60]. The U.S. Ending the HIV Epidemic plan calls for confronting stigma by engaging community voices and leaders to shape policy and perception shifts from within affected groups [61].

Such plans spur concrete policy actions like anti-discrimination laws protecting employment, housing, and medical access for those living with HIV. Currently, 75 countries report constitutional prohibitions against discrimination based on health conditions like HIV status [62]. Rights-grounded reform initiatives like the Global Commission on HIV and the Law provide blueprints for legal changes to curb punitive laws and stigma facing key populations in epidemics [63].

While gaps remain in enforcement, such anti-stigma policy efforts recognize the barriers that marginalization creates across the HIV care continuum. Stigma has been tied directly to adverse health outcomes, with experiences of discrimination significantly associated with gaps in treatment and care [12, 18]. Policy changes are vital to empower the vulnerable rather than further isolate them.

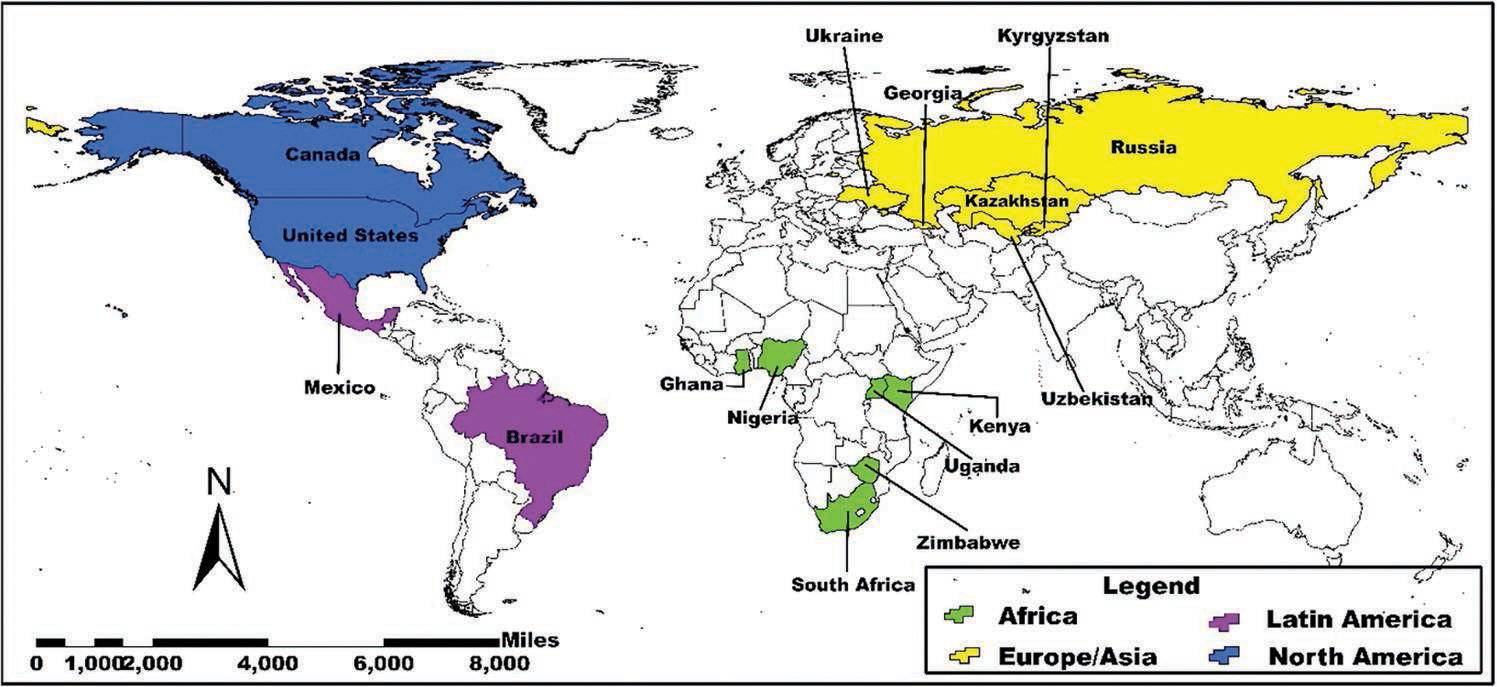

Policy Initiatives Designed to Combat HIV/AIDS Stigma in America, Europe / Central Asia and Africa

North America

United states

The Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative aims to reduce new HIV infections by 90% by 2030, prioritizing efforts in 48 counties/jurisdictions with the highest HIV burdens and rates, many with concentrated epidemics among racial/ethnic minorities, LGBTQ individuals, and other marginalized groups facing disparities [64]. Specific strategies include the Stigma & Syndemics Index to map barriers like stigma, racism, and poverty at local levels to inform targeted interventions. It cites research linking stigma to poorer HIV outcomes [65]. Other plans involve expanding pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) access, responding to HIV hotspots and clusters, and investments in community outreach, healthcare workforce development, and LGBTQ-affirming care models [66].

Canada

Canada estimates 62,790 people were living with HIV in 2020. Key affected populations include gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (54% of new infections), people who inject drugs (21%), and Indigenous peoples (11%) [67, 68]. The Canadian government has implemented several policy initiatives and strategies through its Federal Initiative to Address HIV/AIDS in Canada, aimed at reducing stigma that serves as a barrier for key populations affected by HIV. Launched in 2005, this initiative provides targeted funding and support programs to tackle HIV stigma and the social drivers enabling the epidemic’s persistence among marginalized groups [69, 70].

A major component has involved public education and awareness campaigns to challenge myths and stereotypes and promote inclusion of people living with HIV. This includes the national “HIV Stigma: Unmasked” campaign as well as targeted efforts like “Don’t Guess, Get Tested” focused on reducing stigma as a deterrent to HIV testing among communities with high prevalence rates [71]. The initiative has also advanced legal and policy reforms to uphold human rights protections for key populations facing compounded stigmas, such as LGBTQ individuals, sex workers, and people who use drugs. It has guided provinces and territories in modernizing laws and policies contributing to HIV stigma [70].

Significant investments have been made in community-led responses delivering frontline HIV services, outreach, and support tailored specifically to affected groups facing intersecting stigmas. Examples include grants for harm reduction programs, Indigenous HIV/AIDS organizations, LGBTQ youth-focused programs, and initiatives providing training to combat HIV-related stigma [72, 73]. Additionally, Canada conducted a comprehensive HIV Stigma Index study to systematically document experiences of stigma and discrimination faced by people living with HIV across healthcare, employment, housing, and other settings. The findings informed subsequent programs aimed at responding to key concerns identified by populations such as confidentiality breaches, denial of services, workplace discrimination, and other stigma-related issues [74].

Latin America

Brazil

Brazil has implemented a comprehensive national HIV/AIDS strategy that pairs biomedical interventions with social initiatives explicitly targeting stigma and discrimination as drivers of HIV vulnerability among key populations. With the largest epidemic in Latin America affecting an estimated 900,000 people [75], Brazil has prioritized HIV service delivery tailored to marginalized groups like LGBTQ individuals, sex workers, people who inject drugs, and Indigenous communities facing intersecting stigmas [8]. This involves funding community organizations and NGOs to provide condoms, HIV testing, PrEP, and linkage to treatment in culturally appropriate, stigma-free settings customized to each group’s specific needs [8, 76]. Brazil has also enacted legal reforms decriminalizing same-sex relations and drug possession for personal use, while implementing anti-discrimination laws prohibiting denial of services to those living with HIV and protecting the rights of populations vulnerable to HIV, such as transgender and sex worker communities [77]. Policy development actively engages representatives from affected communities to understand persistent stigma issues and service gaps, promoting leadership and empowerment. Complementing these efforts are public education campaigns using multimedia platforms to counter stigmatizing attitudes, promote LGBTQ inclusion, raise rights awareness among key groups, and encourage access to HIV prevention and treatment without judgment or discrimination [78]. While challenges remain, Brazil’s multi-sectoral approach coupling biomedical strategies with rights-based policies and destigmatizing initiatives tailored to marginalized populations represents a model response for controlling epidemics disproportionately impacting the most vulnerable groups.

Mexico

Mexico has enacted several legal reforms to protect the rights of key populations affected by HIV/AIDS and reduce stigma and discrimination. The 2019 reforms to the General Health Law prohibited denying healthcare services based on HIV status, gender identity, or sexual orientation. It also banned discrimination against key groups in the workplace and educational settings [79]. Sex work has been decriminalized in some states like Mexico City to reduce marginalization and stigma faced by sex workers [80]. Federal labor laws prohibit workplace discrimination against LGBTQ individuals and other key populations such as people who use drugs. However, critics note inconsistent enforcement and gaps remain, as Mexico still lacks comprehensive federal anti-discrimination legislation [81].

Mexico’s National HIV/AIDS Program “Promoting Prevention, Stigma Reduction and Access” prioritizes strategies to reach vulnerable key populations. It funds community outreach, peer education, and service delivery models tailored to counter stigma in specific key groups. Through the program, Mexico has expanded HIV testing sites, clinics, and mobile units in locations more accessible to marginalized groups and setting targets to increase linkage to HIV care among key populations [82]. Mexico also embarked on training healthcare workers on stigma/discrimination, providing LGBTQ-inclusive and culturally competent services and scaling up HIV self-testing options to bypass anticipated stigma in healthcare settings for some groups [83]. While gaps remain in fully addressing compounded stigmas facing key populations like sex workers and migrants, Mexico has implemented a multipronged policy approach involving legal reforms, community-tailored services, health system initiatives, and awareness efforts to mitigate stigma as a barrier to HIV services.

Europe/Central asia

The Dublin Declaration on Partnership to Fight HIV/AIDS in Europe and Central Asia, adopted in 2004, unified 55 countries in addressing HIV/AIDS stigma, discrimination, and marginalization. Recognizing the disproportionate impact of HIV on groups such as sex workers, people who use drugs, migrants, racial/ethnic minorities, and LGBTQ individuals, the declaration emphasized the need for comprehensive national strategies. These strategies include legal and policy reforms, public awareness campaigns, and healthcare initiatives to reduce stigma and improve access to HIV services [84]. Key initiatives involve decriminalizing behaviors associated with key populations, enacting anti-discrimination laws, and integrating HIV services with broader healthcare. Additionally, training programs for healthcare providers and funding for community-based organizations have played a crucial role in these efforts [85].

Countries like Georgia and Russia have implemented targeted national HIV strategies, including legal reforms, public awareness campaigns, the integration of HIV services with other health services and efforts to reduce stigma in healthcare settings [86] while regional cooperation in Central Asia, such as in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan, focuses on joint initiatives for migrants and mobile populations [87]. Future efforts should prioritize strengthening legal protections, enhancing public education, improving data systems, and supporting community initiatives.

Ukraine

Ukraine has a relatively high HIV prevalence concentrated among key affected populations such as people who inject drugs (22.5% prevalence), sex workers (5.2%), and LGBTQ people and their sexual partners [88]. With strong civil society involvement, Ukraine’s National HIV/AIDS Program aims to address stigma, discrimination, and human rights barriers through legal reforms, healthcare worker trainings, anti-stigma campaigns, and increasing community-led service delivery [89].

Africa

South africa

South Africa has undertaken multipronged efforts to counter stigma as part of its robust HIV response. The South Africa National Strategic Plan for HIV sets specific aims, including reforming laws that deter marginalized groups from accessing care, promoting public awareness to reduce stigma, and building healthcare worker capacity on stigma and discrimination issues [90]. Their HIV Investment Case also modeled goals for significantly reducing stigma by 2023 through protections, training, and engagement [91]. Research on South Africa’s policy response has cited remaining gaps in enforcement but highlighted the vital role stigma-reduction initiatives play in promoting epidemic control [92].

Kenya

Kenya’s National AIDS Control Council has emphasized community-centered approaches to counter stigma in its strategy, pushing decentralization of policymaking to enhance local voices, while seeking to promote legal literacy and rights awareness from the grassroots levels on up [93]. Critics argue more urgency is still needed regarding stigma in healthcare settings and employment discrimination, where biased attitudes still limit engagement in testing or care among key groups [94].

Uganda

Uganda became an early pioneer in confronting HIV stigma through open public health messaging and multisector engagement. Their response has been analyzed as conducting vital perception change nationally to reframe AIDS as a disease impacting all communities [95]. Nonetheless, rights groups still cite the need for stronger legal protections and policy reform to counter stigma against LGBTQ individuals and sex workers [96]. Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Act, initially passed in 2014 and later nullified on a technicality, criminalized homosexuality with severe penalties, including life imprisonment for “aggravated homosexuality” [97]. Although nullified, subsequent versions and other related laws continue to foster a hostile environment for LGBTQ individuals. The legislation which was finally passed in May 2023 has significantly heightened stigma and discrimination against LGBTQ individuals, forcing many into hiding and discouraging them from seeking healthcare services for fear of arrest or violence [98]. The criminalization of homosexuality hampers public health efforts by driving LGBTQ individuals away from HIV testing, prevention, and treatment services. Fear of legal repercussions and discrimination by healthcare providers leads to lower uptake of these essential services, undermining the effectiveness of HIV interventions [99].

Zimbabwe

The National AIDS Council (NAC) of Zimbabwe developed the National HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan (2021–2025), which includes specific objectives for reducing stigma and discrimination. The plan promotes the rights of key populations and aims to integrate HIV services with broader health services to reduce stigma [100]. Although Zimbabwe faces challenges in legal reforms due to conservative societal norms, efforts have been made to protect the rights of key populations. Advocacy groups continue to push for legal changes that decriminalize same-sex relationships and protect sex workers from discrimination [101]. Programs like the Community-Led Monitoring (CLM) initiative, public education and campaigns such as “Zimbabwe National HIV,” and AIDS awareness and peer education programs for sex workers and MSM have advanced progress to dispel myths and reduce stigma [100, 102].

Nigeria

In Nigeria, several policy initiatives and strategies have been implemented to address HIV-related stigma among key populations such as sex workers, people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, and transgender individuals. The National HIV/AIDS Strategic Framework (2019–2021) developed by the National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA) emphasizes reducing stigma and discrimination by creating an enabling environment that respects the human rights of people living with HIV/AIDS, and key populations [103]. The HIV/AIDS Anti-Discrimination Act of 2014 prohibits discrimination based on HIV status in employment, education, healthcare, and other sectors, providing legal protection for PLWHA and key populations [104]. Public awareness campaigns like the “Know Your Status” initiative aim to reduce stigma by increasing awareness about HIV transmission, prevention, and the importance of testing and treatment, often featuring influential public figures [105]. To reduce stigma within healthcare settings, NACA and other organizations have implemented training programs for healthcare workers, focusing on sensitizing providers to the needs of key populations and promoting nondiscriminatory practices [103].

Ghana

Ghana has taken some policy steps to address HIV/AIDS stigma, but significant gaps remain according to a recent analysis [106]. Ghana’s current National HIV Strategic Plan calls for strengthening legal protections against discrimination while using mass media and community outreach to promote stigma reduction and gender equity as part of the epidemic response [107]. However, a comprehensive review found stigma persisting as a major barrier to testing, disclosure, and engagement in care among key populations [108]. Contributing factors included lingering taboos discussing sex and LGBTQ issues, lack of confidentiality protections and a tendency to conflate HIV with immorality [106].

Gaps cited included limited stakeholder coordination on stigma issues in the response, lack of firm targets or timelines for stigma reductions, and the need for broader legal reforms on longtime criminalization of issues like sex work and same-sex relations contributing to marginalization and perceived stigma-deterring care [109].

Experts have argued Ghana must learn from shortcomings thus far, better spotlight the lived experiences of those facing stigma, and expedite policy changes if eliminating AIDS as an epidemic threat remains the goal by 2030 [110]. A strong legal and ethical imperative based on human rights considerations also demands confronting biases limiting equitable access among key groups.

In Ghana, while homosexuality is criminalized under Section 104 of the Criminal Offences Act, 1960, recent efforts to introduce more stringent anti-LGBTQ laws have further intensified stigma and discrimination [111]. The Ghanaian anti-LGBT bill, officially known as the Human Sexual Rights and Family Values Bill, received bipartisan approval from the Parliament of Ghana on February 28, 2024, and will become law if signed by President Nana Akufo-Addo. This legal bill if officially passed will not only perpetuate social inequities but also undermine public health efforts by driving key populations away from essential HIV prevention, care, and treatment services [112].

Innovative healthcare access models

Novel approaches that bring integrated services directly to underserved groups have shown immense promise, expanding access and overcoming stigma-related barriers to care.

Mobile health clinics

Mobile clinics like South Africa’s Ukuphepha program leverage retrofitted buses and pop-up tents to provide one-stop integrated testing, primary care, PrEP, sexually transmitted infections (STI) checks and mental health services wherever high-risk or difficult-to-reach groups live and gather [113]. By meeting people where they are at geographically and regarding risk profiles, mobile efforts overcome not only geographic isolation but also the stigma some still feel entering traditional clinic settings [114].

Telehealth and mhealth expansion

Similarly, expanding telehealth and mobile health (mHealth) options enhances confidential engagement on sensitive topics [115]. The Technology-Enhanced Prevention (TEP) program in New York successfully employed text campaigns and app counseling to promote sexual health and PrEP uptake among vulnerable youth [116]. Especially for legally or socially marginalized populations like LGBTQ homeless youth and sex workers, technology can provide vital links to nonjudgmental care.

Syringe service programs

Reaching intravenous drug users through syringe service programs (SSPs) has also created links to integrated testing, treatment, and prevention lacking through traditional systems [117]. Model SSP initiatives like New York’s well-established programs have pioneered expanding from narrow needle exchange to now serve as fully integrated one-stop healthcare and social support access points for highly stigmatized groups [118, 119]. The model dissolves assumptions by meeting PWID where they are while expanding options.

Peer navigation programs

Peer navigation programs leverage shared lived experiences between program staff and clients to provide counseling, service referrals, and social support to improve engagement across the HIV care continuum [54]. Studies show peer navigators are uniquely effective in increasing appointment attendance, medication adherence, and viral suppression among groups facing substantial stigma such as transgender women, racial/ethnic minorities, uninsured populations, and those experiencing homelessness [120]. The approach helps build trust and a sense of community.

Faith-based initiatives

Partnerships between healthcare systems and faith-based organizations help promote testing and linkage to care through trusted community institutions, while also reducing stigma by framing health outreach as fulfilling moral missions [121]. Programs emphasizing compassion and supporting marginalized parishioners and broader communities impacted by HIV show success in engaging groups often alienated from traditional providers [122].

LGBTQ-centered clinics

Healthcare facilities specifically catering to LGBTQ populations through LGBTQ-identified staff and appointment flexibility provide vital judgment-free care access for patients reporting stigma who are avoiding mainstream providers [123]. LGBTQ-centered clinics focusing on sexual health, primary care, PrEP, and transition-related services for transgender patients represent promising models for further expansion.

A vision for the future

Advocacy groups, researchers, and health leaders have increasingly argued ending AIDS requires not just medical innovations but also profound social and political transformations. Calls to action span from advocacy to policy reform.

Calls to action across sectors

Global leaders must heed growing calls for urgent action on equitable access and demarginalization. Political leaders have opportunities to catalyze change through funding commitments, appointments representing affected groups, and reforming punitive laws [124]. Healthcare systems must enhance provider training, diversify workforces, and expand access options to create welcoming, stigma-free services for vulnerable patients [125]. Local community leaders play vital roles in engaging grassroots voices, supporting peer advocates, and using platforms to endorse equity [93].

Policy and legal strategies

Structural reforms remain vital to empower the vulnerable groups the epidemic persists among rather than further isolating them through stigma or criminalization. Calls persist for decriminalizing consensual adult sex work and same-sex relations, alongside enacting antidiscrimination protections for gender identity, sexual orientation, and health conditions like HIV status [62]. Such legal levers can alleviate marginalization fueling transmission risks and barriers to equitable care [109].

Role of activism and social change

Ultimately, activism efforts spurring social change may represent the most vital accelerant to ending AIDS stigma. Campaigns empowering affected individuals to share stories, organize, advocate for rights, and demand reforms structurally and locally have shown promise in altering biases and barriers facing key groups [126]. Where laws and leaders fail marginalized communities, pushback may force action – offering hope that collective action can achieve what inequality and indifference obstruct.

Structural reforms

Groups like UNAIDS and the Global Commission on HIV and the Law have issued specific structural reforms for governments to enact, spanning decriminalization of consensual sex work, drug use, and LGBTQ relations to prohibiting discrimination in housing, workplaces, and healthcare based on gender, sexual orientation, or health condition [62, 127]. Where communities face marginalization in societies due to not conforming with majority identities or activities, perceived stigma creates immense barriers to equitable care and fuels transmission risks in shadowed spaces beyond preventative outreach. Policy-level reforms have the potential for sociocultural impact.

Healthcare system changes

Healthcare providers and institutions also carry obligations to reduce biases limiting engagement in care. Recommendations include expanding curriculums for healthcare professionals focused on serving key populations; requiring demonstrated competencies serving LGBTQ patients; enhancing workforce diversity; and reforming modalities like telehealth, community health workers, and mobile clinics to alleviate stigma in accessing traditional facilities [17, 96]. Quality improvement initiatives at healthcare organizations focusing specifically on metrics of care equity and inclusion for marginalized patients also provide internal accountability.

Community empowerment

Grassroots advocates argue sociocultural shift relies on community empowerment through groups directly impacted by shaping understanding and responses. Concepts like “community viral load” recognize the public health impacts of empowering communities to take ownership of health outcomes and support structures for their most vulnerable members [128]. Platform amplification for the experiences of those facing HIV-related stigma also proves vital in combating misconceptions [126]. Paternalistic policymaking alone cannot manifest the empathy and understanding needed to end systemic neglect and barriers facing groups long marginalized.

Limitations of the Review

This narrative review methodology allowed for a comprehensive literature synthesis, including qualitative, quantitative, and review papers, and the exploration of complex phenomena such as stigma and marginalization. However, this review, like most narrative reviews, lacks the systematic and structured methodology used in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. This may have led to selection bias, as the inclusion and exclusion of studies were more subjective and did not follow a rigorous predefined protocol. Due to this, this review is likely to be less reproducible. An additional limitation is that no formal quality assessment of the included studies was performed, leading to the inclusion of studies with varying levels of quality, potentially impacting the reliability and validity of the review’s conclusions.

Conclusions

Ending the epidemic waits not on lab breakthroughs but on openness breaking down walls excluding fellow humans from dignity, understanding, and support. It demands not charismatic leaders grasping at quick fixes, but collaborative accountability across sectors to meet the vulnerable where they suffer lack – of housing, income, rights, justice, and access to assistance keeping others alive.

With care equitably delivered, arms locked in shared purpose, moral allies elevating rather than condemning lives once disregarded, science maximizing potential through social conscience may at last halt AIDS. The tools to end infections exist through policy reforms, healthcare equity, and sociocultural inclusion affirming rights, value, and access for all people impacted. But first, shared responsibility must manifest through action as open as the arms waiting to embrace those whom stigma leaves isolated for far too long already. Past experience tells the only just path forward now converges where open arms meet open access with open minds, banishing biases threatening the shared dream of an AIDS-free world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S.B., E.K., and S.A.; Conducting the literature search, D.S.B., E.K., and S.A.; Writing – original draft preparation, D.S.B., E.K., and S.A.; Writing – review and editing: D.S.B., E.K., and S.A.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

All data set is within the manuscript.