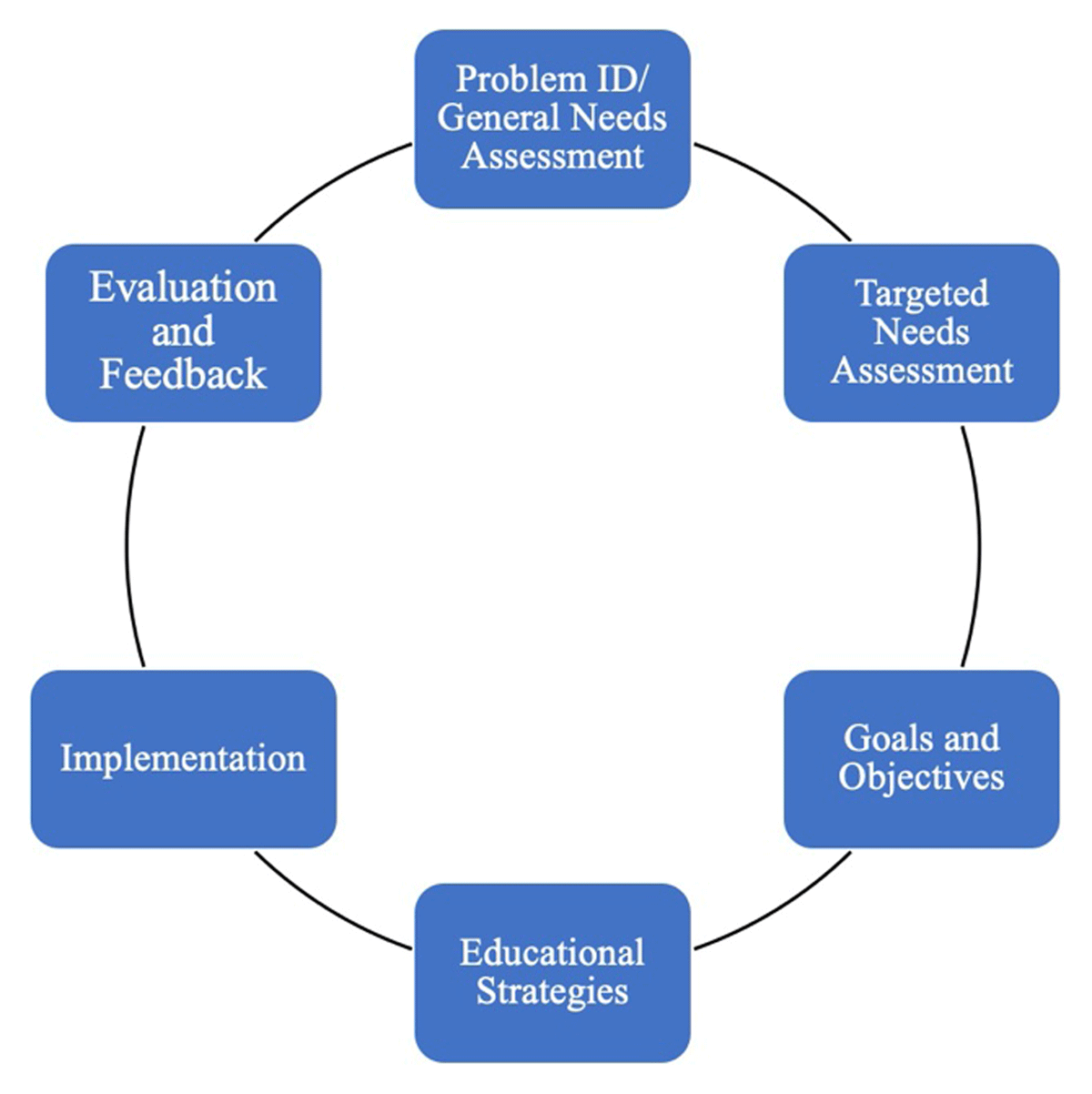

Figure 1

Six-Step Curriculum Development Framework.

Table 1

Comparative Analysis of Global Public Health Leadership Program Curricular Approaches.

| CURRICULUM STEP | AFYA BORA | STAR PROJECT | GLOBAL HEALTH CORPS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial matriculation | 2011 | 2017 | 2009 | |

| Main collaborators | African Partners:

US partners

| Public Health Institute (PHI) Johns Hopkins School of Public Health (JHSPH) Consortium of Universities for Global Health (CUGH) University of California San Francisco (UCSF). | 150+ partner organizations including Ministries of Health, INGOs, and grassroots organizations across the USA, East and Southern Africa | |

| Total enrollment to date | 189 (162 alumni, 27 current fellows) | 115 (69 fellows, 46 interns) | 1,028 alumni | |

| Program duration | One year fellowship. | Two years for fellows and 3–12 months for interns. | 13 months fellowship; career-long support for alumni. | |

| Steps 1 and 2: Problem Identification and Needs Assessment | Problem statement | Lack of health professionals with leadership and management skills to manage HIV/AIDS programs. | Lack of highly skilled public health workers to fulfill technical roles in local (LMIC focused) global/public health programming. | Lack of diverse leaders in non-clinical public health roles Lack of individuals with the leadership skills, management skills, and professional network necessary for systems change. |

| Current approach (status quo for leadership and management in global health programming) | Practitioner perspective There is an increasing need for health professionals trained to fill in the gaps in leadership and management for the growing number of health-related programs in Africa. Most often these positions are filled by expatriates due to lack of expertise among local health care professionals. Education perspective Majority of training programs in Africa focus more on clinical skills as opposed to inculcating leadership skills in their trainees. This has led to well-trained clinicians able to manage patient illnesses but unable to develop and run health programs. Finding leadership and management training opportunities is left up to individuals; many must travel abroad, which creates inequities by limiting training for those with means to travel. | Practitioner perspective US residents often fill technical leadership roles for USAID programs. Professionals focus on individual advancement and technical skills; ongoing education is often not planned and relies on apprenticeship. Education perspective USAID has invested in internal training modules available to their employees. HIC-based graduate programs are classroom-based and misaligned with priorities of practitioners. Online options are expanding but require time and internet access and are limited in their interactivity, assessment, and evaluation options. | Practitioner perspective Non-clinical healthcare workers address critical capacity gaps in public health organizations. Underinvestment in the recruitment, retention, and training of diverse non-clinical health workers results in weak and vulnerable health systems. Education perspective Many training and education programs overvalue technical skills and neglect the importance of leadership and management skills-building for achieving global health outcomes. Practitioners are therefore unprepared to respond or adapt to the challenges and systems leadership required to transform complex health systems. | |

| Ideal approach (what our programs are aligned to contribute towards) | Practitioner perspective Leadership and management training capacity for health professionals in Africa can be enhanced through collaborations among local governments and implementing partners. Education perspective Leadership and management modules tailored to health systems should be integrated to existing health-related curricula. The mode of training should emphasize practical/attachments to enable acquisition of skills and experiences in organizations that also have an immediate impact. | Practitioner perspective USAID and other leading international development agencies around the world should provide incentives to invest and share resources with colleagues. Practitioners should access training that will improve their performance and particular work expectations while serving as technical leads and partnering with host country governments. Education perspective Relevant educational opportunities should be available broadly to the global health workforce. Teams and organizations should think systematically about supporting ongoing learning. Learning should be targeted towards the needs of individuals and the programs they support. | Practitioner perspective Global health organizations should have access to a reliable talent pipeline of diverse, non-clinical staff who have the leadership and management skillsets to successfully lead complex initiatives. Education perspective Leaders should be prepared with the leadership and management skillsets to successfully navigate and lead complex change. Leadership and management acumen are considered as essential as technical skillsets. | |

| Target learners | Doctors, nurses, and public health professionals drawn from Ministry of Health, Non-Government Organizations (NGO), Academic Health Institutions. | USAID, Ministries of Health, and NGO managers and technical leads focused on public health programs. | Young professionals (ages 22-30) from diverse national, racial, ethnic, and professional backgrounds. | |

| Step 3: Goals and objectives | Overall goals of the curriculum |

|

| Fellows are equipped to be effective leaders who excel in their careers, collaborate with each other, and influence the field of global health. |

| Competency domains |

|

| Leadership and management skills are addressed in four areas:

Technical skills are developed through workplace learning and supplementary programming. | |

| Step 4: Educational Strategies | Educational strategies and pedagogical approaches | One year fellowship that includes interactive didactic sessions for eight weeks and two 4.5 months attachment site rotations (mentored project oriented rotations) Fellowship meetings The fellows attend three fellowship meeting that include orientation, mid-fellowship and final meetings. During the meeting, plenary presentations are made on current issues in Global Health by guest speakers, networking with mentors and alumni and fellows make presentations on their projects. Didactic sessions Fellows undergo face-to-face lectures, case studies, and discussions in interprofessional teams. Attachment site placements These provide practical skills and offer a chance to implement materials learnt from didactic sessions. During the placement the fellows are supervised by site mentors. Individual fellows are expected to undertake a project that benefits the organisation during the placement under the guidance of mentors. Alumni engagement The program offers competitive support for a career development project and attendance of networking forums, including fellowship meetings and conferences. | Two-year fellowship and three-month to one-year internships. ILP Development of individualized learning plans (ILP) for each participant at the outset of the fellowship, which is monitored and revised as needed throughout. This plan helps participants organize and anticipate learning needs and develop a holistic and coherent package of learning over the course of the program. Deliberate Practice A deliberate practice approach is utilized linking learning with work performance. Hybrid Mentorship A hybrid mentorship model was developed and is utilized with peer mentorship groups that focus on core competencies and need-driven sessions on topics informed by the priorities of each particular group as well as general public health challenges, such as the COIVD-19 response. In addition, individual technical mentors are assigned as requested. | Experiential Learning Paid 13-month fellowship with placement organizations working on the frontlines of global health in Malawi, Rwanda, Uganda and Zambia. Co-Fellow Model We place fellows in pairs—one national and one international fellow—within each organization, to promote cross-cultural learning and collaboration. Training and Community Building Fellows meet regularly with their cohort for workshops and community building activities. Professional Development Fund Fellows can apply funding to pursue individual learning opportunities. Mentorship/Coaching Provided by staff, advisors, alumni, and supervisors. Career-long Support Fellows join an alumni community and access ongoing support as they advance in their careers, collaborate with each other, and influence the field of global health. |

| Step 5: Implementation | Core Curriculum Consists of eight one-week didactic modules and two workshops (one to two days each) and four distance learning modules Delivery: Based on case studies, Problem based learning approach, Group work and presentations with minimal power-point lectures Attachment site rotations Act as areas for experiential learning, sites located in African partner countries including Government facilities (MOH), NGOs, International Health organizations—CDC, USAID. Post fellowship networking This is through provision of networking platforms and support of ongoing career activities | Onboarding Participant onboarding includes a goals development activity, a baseline competency assessment, and the development of an ILP. Each ILP reflects work-related goals as well as longer-term career goals in a set of specific and individualized learning objectives. The ILP is a contract between the participant, their onsite manager at USAID, and STAR for time and budget allocation for the participant to devote to learning. Program period Once onboarding is completed, participants embark on their jobs and complete the activities laid out in their ILP. The STAR learning team also engages them in group mentorship groups and other program-wide opportunities. Each participant has check-ins every six months to monitor progress and to course-correct as needed. Program wrap-up Each participant completes an evaluation of the learning experience as well as on each specific activity that they completed. They also complete an endline competency assessment to demonstrate changes in skills and knowledge, particularly across the eight core competencies. | Recruitment and Placement We recruit and place a diverse pool of talented young professionals on the front lines of global health. Our leaders fill critical gaps within our competitively selected partner organizations, honing the skills needed to transform health systems throughout their careers. Leadership Programming We design and implement a transformative, robust leadership development curriculum. Community Building We build a tight-knit community to harness the power of collective leadership. Through summits, trainings, an online portal, and regional chapters, our leaders collaborate across borders and boundaries, amplifying their impact and influence. | |

| Step 6: Evaluation and Impact | Assessment and evaluation approach | Feedback by fellows on all modules Attachment sites: Completion of bi-weekly journal describing experiences Weekly meeting with site mentors Monthly meetings with primary mentors and peer reviews by fellows Completion of evaluations by mentors and Mentees Final evaluation: Final report Post fellowship: Biannual surveys for alumni—track career progression/long term impact. Feedback from fellows and evaluators used to improve curricula | Evaluation of the program was driven by the development of a theory of change and associated metrics to measure impact. Baseline assessment of participant competence and career goals was conducted for each participant. Regularly monitoring of learning progress was undertaken on an annual basis as well as less formally by project staff. An endline assessment of impact at individual and team levels was also conducted. | Conducted formal impact evaluation in 2018 in partnership with Dr. Amy Lockwood (University of California, San Francisco). These findings informed a new Theory of Impact and a system of impact metrics that measure how GHC impacts our fellows and how our results link to progress in global health. Feedback collected through regular surveys, individual check-ins, and group sessions |

| Impact achieved | Post fellowship alumni surveys are conducted that cover the following topics:

The Afya Bora Consortium has seen positive changes across these indicators and has published more detailed findings elsewhere. | Over the two years since STAR has actively been working with participants, a number of results have been achieved. In addition to onboarding participants on a rolling basis, we have established a learning activities database from which to draw activities for participants at different levels across the core competencies as well as for specific technical and content areas. We have also monitored learning plans and identified gaps in available activities. In response to several gaps, in particular related to public health ethics and gender equity, we have developed tailored modules for STAR participants. More data on the impact of the program is forthcoming as we begin to have participants complete the program and shift further attention towards monitoring and evaluation. | GHC identifies and supports a diverse community of effective leaders…

who excel in their careers…

collaborate with each other…

and influence the field of global health.

| |

| Scalability/Sustainability | The main challenge in sustainability has been funding. Training of fellows in their home country/local organizations increases retention and ensures sustainability. | Sustainability of learning budgets is a challenge. Learners still struggle to protect time for learning, even when it is part of their contracts. The learning activities database requires regular updates in order to remain current, which is labor-intensive. Looking ahead, STAR is aiming to identify more ways to align with USAID priorities and engage key partners in sustainable ways. | Partner organizations continue to exhibit high demand for fellows as a proven talent pipeline. GHC’s pathways to scale include leveraging strategic partnerships for: work placements, training, thought leadership, networking and seed funding for alumni initiatives. | |

| Lessons learned | It is possible to implement a leadership fellowship for health professionals that has impact in improving health systems in Africa. Collaboration with government and local partners is key in success The north to south collaborations/networking are important in increasing diversity and opening up opportunities post fellowship | Buy-in and support from partners and funders is critical for equitability and success of such programs. Strong communication links between learning teams and other supervisors can help mitigate challenges. | Value of strategic partnerships Funder strategy—complementary to other global health efforts Alumni investment (network) |