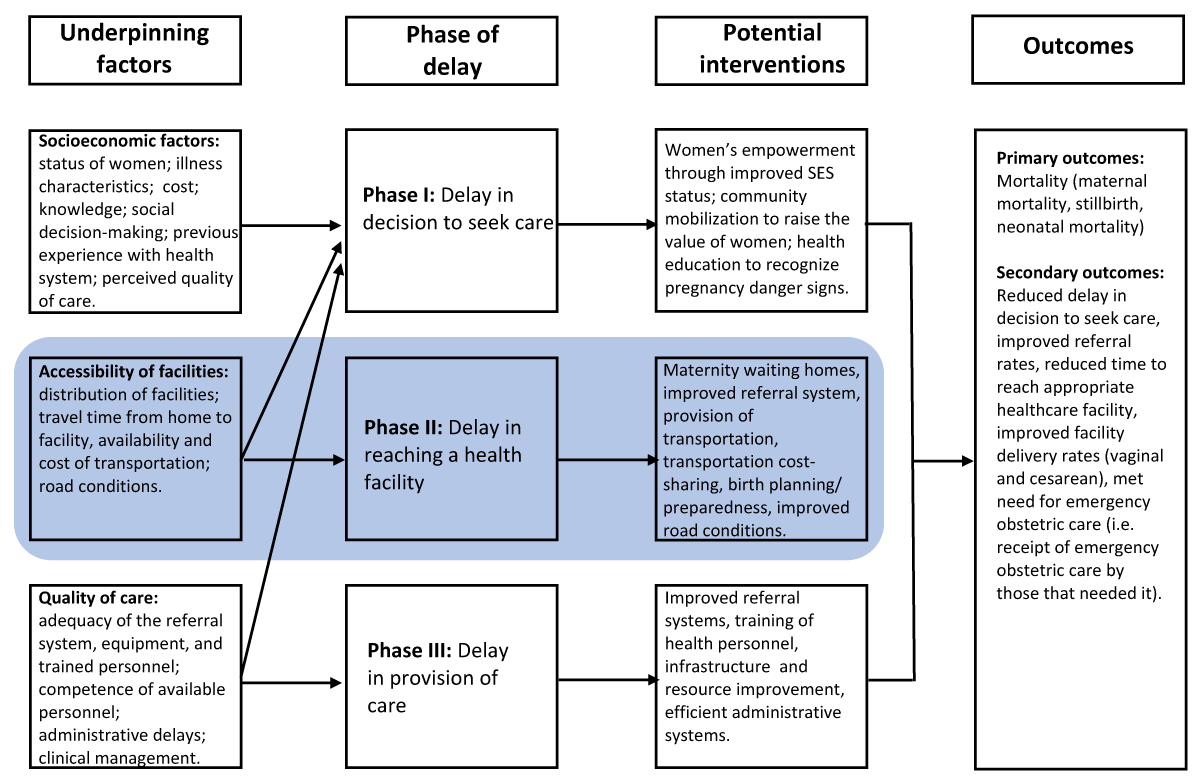

Figure 1

Conceptual framework for the review, based on the three-delay model.

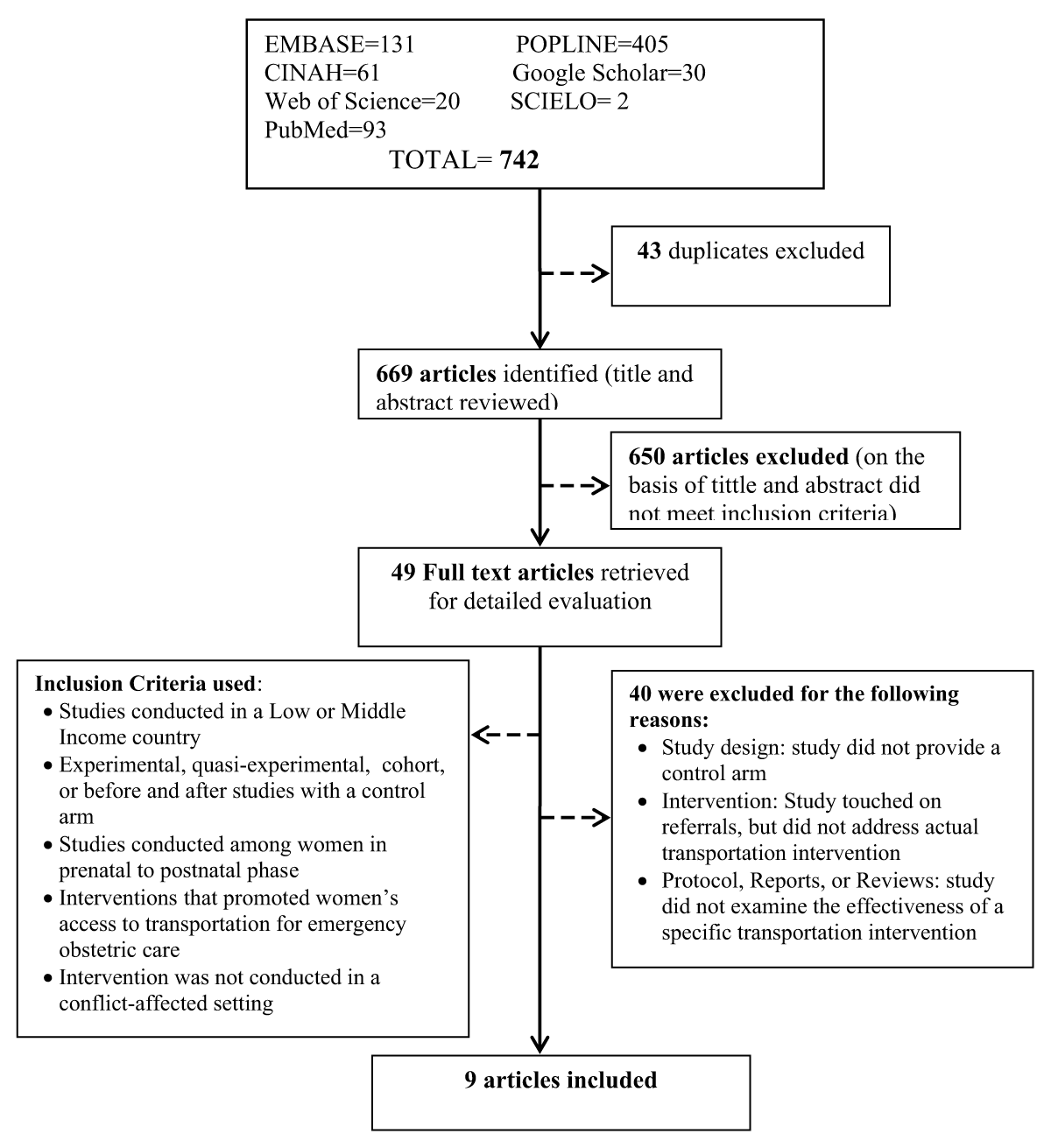

Figure 2

Literature Search Process and Results.

Table 1

Characteristics of included studies.

| Author (year) | Objectives | Study Design | Study Population | Intervention and Follow-up | Outcomes Measured | Key Results | Critical Appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lungu et al. (2000) | To evaluate the effectiveness of two interventions (bicycle ambulances and established transport plans) in decreasing home delivery rates | Case-control study | Women of childbearing age who delivered in Nsanje District of Malawi |

| Home deliveries | Bicycles ambulances: 51.2% Transport plan: 9.8% Home deliveries in case villages decreased from 37% to 18% |

|

| Referrals | Control: 39% Bicycle ambulances: 20% of referrals to the health facilities were for obstetric reasons. |

| |||||

| Transport time |

|

| |||||

| Cost-effectiveness | Bicycles ambulances: MK15 Transport plan: MK 0.30 Control: MK 0 |

| |||||

| De Costa et al. (2009) | To evaluate the effectiveness of financial support for transportation in reducing maternal deaths | Control before-after study | Women 15–45 years of age from scheduled castes and tribes as well as those who live below the poverty line in central India |

| Maternal death | Intervention: pre (27); post (12) Control: intervention year (46) |

|

| Live births | Intervention: pre (5,084); post (5,221) Control: intervention year (7,662) | ||||||

| Maternal mortality ratios | Intervention: pre (531); post (249) Control: intervention year (600) | ||||||

| Maternal death occurring at home | Intervention: pre (55.6%); post (25%) Control: intervention year (58.7%) 89% of deliveries occurred at home in intervention block | ||||||

| Post-partum death | Intervention: pre (55.6%); post (25%) Control: intervention year (58.7) |

| |||||

| Referral support | Intervention: 23.8% advised referral availed the referral benefits. |

| |||||

| Mucunguzi et al. (2014) | To evaluate the effectiveness of a free-of-charge 24-hour ambulance and communication services intervention on emergency obstetric care outcomes | Control before-after study | Pregnant women from two districts of Northern Uganda |

| Hospital stillbirths per 1000 births | Intervention: pre (46.6%); post (37.5%) |

|

| Hospital deliveries | Intervention: pre (1090); post (1646) Control: pre (1776); post (1810) Hospital deliveries increased by over 50% in intervention district | ||||||

| Caesarean sections rates | Intervention: pre (0.57%); post (1.21%) Control: pre (0.51%); post (0.58%) No significant increase in the control district | ||||||

| Cost of intervention | USD 1,875 per month. | ||||||

| Prinja et al. (2014) | To assess the extent and pattern of NAS utilization, and whether NAS service has improved the utilization of public sector facilities for institutional deliveries | quasi-experimental design uncontrolled before-and-after | Pregnant women from Ambala, Hisar, and Narnual districts in Haryana state, India | Haryana Swasthya Vaahan Sewa (HSVS), now known as National Ambulance Service (NAS) – a government managed referral transport system with its administration decentralized to district level | Institutional deliveries | Ambala (OR = 137, 95% CI = 22.4–252.4); Hisar (OR = 215, 95% CI = 88.5–341.3) districts; Narnaul (OR = 4.5, 95% CI = –137.4 to 146.4) Institutional deliveries in Haryana rose significantly after the introduction of HSVS service, however, no significant increase was observed in Narnaul district. |

|

| Goudar et al. (2015) | To assess whether community mobilization and interventions to improve emergency obstetric and newborn care reduced perinatal and neonatal mortality rates | Cluster-randomized controlled trial | Pregnant women from 20 geogra-phically defined clusters in Belgaum, India |

| Neonatal mortality rate | Intervention: pre (26.7); post (18.4) Control: pre (21.2); post (24.1) | |

| Perinatal mortality rate | Intervention: pre (52.7); post (37.8) Control: pre (47.9); post (44.2) No statistical significance was reached for both mortality outcomes. | ||||||

| Transportation | Intervention: pre (74.9%); post (87.1%) Control: pre (77.9%); post (98%) | ||||||

| Caesarean section | Intervention: pre (8.6%); post (13.1%) Control: pre (8.2%); post (13.4%) No significant difference between both groups | ||||||

| Facility birth rates | Intervention pre (87%); post (94%) Control pre (85%); post (93%) | ||||||

| Patel et al. (2016) | To evaluate the impact of community-engaged emergency referral system in improving survival in impoverished rural Ghanaian communities | Control before-after study | Individuals living in the Upper East Region in Ghana |

| Maternal mortality ratio | Intervention: pre (618); post (201) Control: pre (326); post (261) |

|

| Referrals into district hospitals from health centers | Intervention: Increase referrals into district hospitals from health centers by > 12 patients per month (P < 0.005) | ||||||

| Hospital deliveries | Intervention: No significant effect on the number of hospital deliveries (P > 0.05) | ||||||

| Cesarean delivery rate | Intervention: No significant effect on the cesarean delivery rate (P > 0.05) | ||||||

| Fournier et al. (2009) | To evaluate the effect of a national referral system that aims to reduce maternal mortality rates through improving access to and the quality of emergency obstetric care in rural Mali (sub-Saharan Africa) | Quasi-experimental uncontrolled before-and-after | Women with obstetric complications who are referred by community health centres and have benefited from all components of the system, and women who are self-referred to the district health centre. | Intervention: The maternity referral system aimed to:

| Institutional deliveries | Institutional deliveries over expected deliveries: P-1: 9871/52045 (19%) P0: 15576/58453 (27%) P1: 16573/51868 (32%) P2: 19235/48846 (39%) | |

| Obstetric emergencies treated | Referred Obstetric Emergencies treated over all obstetric emergencies: P-1: 143/475 (30%) P0: 273/658 (41%) P1: 246/571 (43%) P2: 452/913 (50%) | ||||||

| Hoffman et al. (2008) | To assess whether motorcycle ambulances are more effective method of reducing referral delay for obstetric emergencies than a car ambulance, and to compare investment and operating costs with those of a 4-wheel drive car ambulance | Uncontrolled before-and-after | Women with obstetric complications in Mangochi district, Malawi | Intervention: Three motorcycle ambulances, consisting of a 250 cc Yamaha motorcycle with sidecar, which could carry 2 adults, were stationed at three remote rural health centers (Makanjira, Mase, and Phirilongwe) in Mangochi district, Malawi. Follow-up: Intervention occurred over a 12-month period from October 2001 to September 2002. | Reduction of 2nd delay | Median referral delay was reduced by 2–4.5 hours (35%–76%). |

|

| Cost-effectiveness | Purchase price of a motorcycle ambulance was 19 times cheaper than for a car ambulance. Annual operating costs of a motorcycle ambulance were US $508, which was almost 24 times cheaper than for a car ambulance. | ||||||

| Ngoma et al. (2019) | Addresses how Saving Mothers Giving Life (SMGL) Initiative in Uganda and Zambia implemented strategies specifically targeting the second delay, including decreasing the distance to facilities capable of managing emergency obstetric and newborn complications, ensuring sufficient numbers of skilled birth attendants, and addressing transportation challenges | Uncontrolled before-and-after | Pre-natal women in SMGL districts in Uganda and Zambia | Intervention: A key element of the SMGL initiative was the creation of an integrated communication and transportation system that functions 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, to encourage and enable pregnant women to access delivery care facilities. Both Uganda and Zambia led several efforts to facilitate transportation to and between facilities. Follow-up: The SMGL initiative in both Uganda and Zambia operated within 3 phases: Phase 0: Design and start-up (June 2011 to May 2012) Phase 1: Proof of concept (June 2012 to December 2013) Phase 2: scale-up and scale-out (January 2014 to October 2017). During Phase 2, SMGL expanded its presence in Uganda from 4 districts to 13 districts, and in Zambia from 6 to 18 districts. | Facility deliveries | Uganda observed a +45% and Zambia +12% relative change in deliveries in Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (EmONC) facilities between Jun 2012 and Dec 2016. Uganda observed a +200% and Zambia +167% relative change in the number of basic EmONC facilities Jun 2012 and Dec 2016. Uganda observed a +143% and Zambia +25% relative change in the number of comprehensive EmONC facilities Jun 2012 and Dec 2016. Zambia observed a +31% and Uganda -3% relative change in health facilities that reported having available transportation (motor vehicle or motorcycle). However, Uganda had a different transport intervention Institutional delivery supported by Baylor transportation vouchers that observed a +258% increase Jun 2012 and Dec 2016. |

Table 2

Intervention components implemented by included studies to improve transportation and reduce delay for obstetric emergencies.

| Study | Intervention Components | Description of Intervention Components | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transportation | Communication | Cost-Sharing | Community Mobilization | ||

| De Costa | No | No | Yes | Yes | Financial support was provided for transportation of emergency referral cases and any accompanying health worker. Incentives also existed for early registration of pregnancy, receipt of antenatal care, and detection of high-risk pregnancies. Transportation (tractors, vans, other modes of transport) was arranged through informal contacts (mobilized community). |

| Fournier | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | A non-descript ambulance service was improved through intervention between health facilities only. Communication was improved with radios. Costs for transportation were shared by local government, local health services, community health associations, and a co-pay from the pregnant women. |

| Goudar | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Community-based workers were trained to effectively communicate with transportation facilitators and hospital staff. Emergency funds were created using personal savings or local resources. Community Action Cycle was used to empower communities to identify, prioritize, and act on maternal and neonatal health problems. This included establishing birth plans and arranging alternative emergency local transportation. |

| Hofman | Yes | No | Yes | No | Three motorcycle ambulances with sidecars were stationed at remote rural health centers. The ambulances were operated by trained Health Surveillance Assistants. They picked women up from their homes and transported them between health facilities (only transportation between health facilities was evaluated in this study). Transportation was provided free-of-charge. |

| Lungu | Yes | No | Yes | No | Two communities used bicycle ambulances and two communities developed transport plans. Communities fundraised to create a maintenance reserve, as determined by financial committees in each site. Communities with transport plans implemented a MK 10 flat rate charge for each trip to the health center. |

| Ngoma | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Various ambulances were procured for different study communities: 4 × 4 ambulances (Uganda and Zambia), motorized tricycle ambulances (Uganda), bicycle ambulances (Zambia), and motorcycle ambulances (Zambia). Transportation was available 24/7, for transport to facilities and referral between facilities. District transportation committees were established or strengthened to coordinate ambulances (Uganda and Zambia). Two-way radios (Zambia) and cell phones and airtime (Zambia) were supplied to facilitate communication. Transportation vouchers and village-level savings programs were used to alleviate cost barriers (Zambia). Village health teams and action groups were trained to encourage birth preparedness and to escort women to facility. |

| Mucunguzi | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | One 4 × 4 ambulance was stationed at the district hospital and provided transportation free-of-charge, 24/7, between health facilities only. Mobile phones and airtime were provided to each health facility to facilitate communication. |

| Patel | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 24 three-wheeled motorcycles with structural modifications for patient safety and comfort were stationed at health centers, health posts, and at homes of chiefs or assembly men in communities with no health facilities. They transported all pregnant women (emergency and normal cases) free of charge. Dual-SIM mobile phones and airtime were distributed to health facilities, health workers, and drivers. A phone line dedicated to receiving incoming calls was established at the tertiary referral point in each ward. Community meetings were held to distribute emergency phone numbers, share information about the ambulance service, and distribute posters to be hung at health facilities and community gathering places. |

| Prinja | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 240 traditional ambulances were stationed at community health centers and primary health centers. Transport was free for pregnant women, neonates, and postnatal cases. A 24/7 call center, with a toll-free emergency number, dispatched ambulances using GIS. |

Table 3

Description of ambulance vehicles used by included studies, with pros and cons for each type of transportation.

| Ambulance Type | Description of Vehicle | Pros for Mode of Transport | Cons for Mode of Transport |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formal ambulance [40]

| A large vehicle, such as a van, with four wheels that transports patients in a rear compartment, usually while laying down. May be stocked with life-saving equipment and medications. Usually equipped with sirens and insignia so that the vehicle is easily identified. |

|

|

| 4 × 4 Landcruiser ambulance [4445]

| A high-clearance vehicle with four-wheel drive that transports patients in a rear compartment, either laying or sitting. |

|

|

| Motorcycle or motorized tricycle ambulance [384245]

| A motorcycle may be fitted with an open or closed sidecar, carriage, or wheeled stretcher that carries a patient and up to one other person. |

|

|

| Bicycle ambulance [4145]

| A bicycle may be fitted with an open or enclosed trailer, carriage, or wheeled stretcher that carries one patient only. |

|

|

Table 4

Methodological quality assessment of included studies using the ROBIS-I tool.

| Author | Confounding | Selection of Participants | Classification of Intervention | Intervention Deviation | Missing Data | Measurement of outcomes | Selection of result Reported | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Costa et al. 2009 | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Low | Serious | Low | Low | Serious |

| Fournier et al. 2009 | Moderate | Moderate | Low | No information | Low | Serious | Low | Serious |

| Goudar et al. 2015 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Hofman et al. 2008 | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Serious | Moderate | Low | Serious |

| Lungu et al. 2000 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Mucunguzi et al. 2014 | Critical | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Critical |

| Ngoma et al. 2019 | Critical | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Serious | Critical |

| Patel et al. 2016 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Prinja et al. 2014 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |