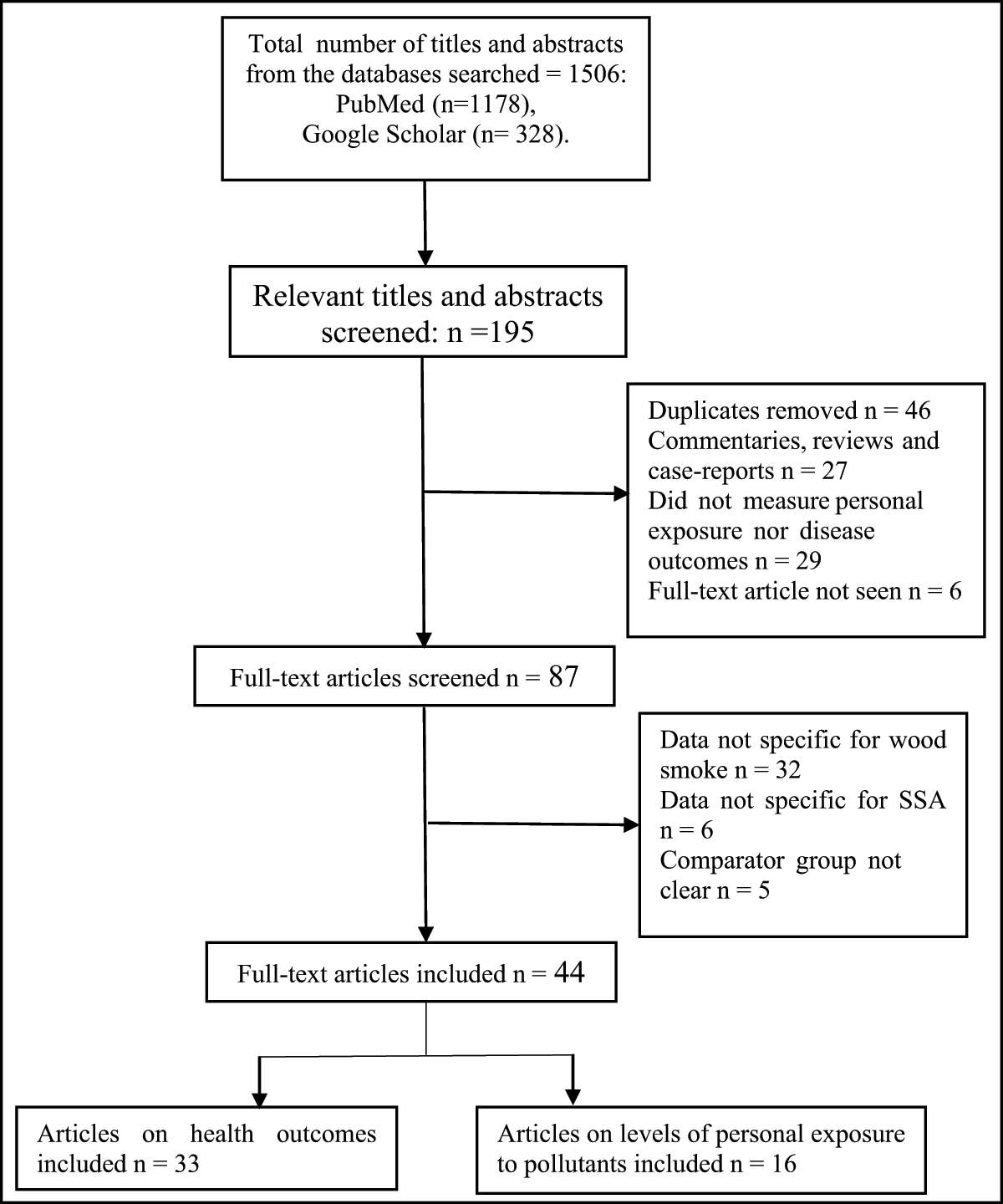

Figure 1

Flow chart of study search and selection process.

Table 1

Summary of epidemiologic studies on levels of exposures to wood smoke pollutants in sub-Saharan Africa.

| Reference (Country) | Study design (Setting) | Study Population (Sample size) | Mean ± SD (Range) | Determinants for higher exposure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal PM10 Exposure | ||||

| Ellegard [35] (Maputo, Mozambique) | CSS (suburb) | Women who are household cooks (Wood users = 114 Charcoal users = 78 Electricity users = 8 LPG users = 3) | Wood: 1200 ± 131 μg/m3 Charcoal: 540 ± 80 μg/m3 Electricity: 380 ± 94 μg/m3 LPG: 200 ± 110 μg/m3 | Wood users were exposed to higher PM10 than charcoal and electricity/LPG users |

| Ezzati et al. [3334]* (Kenya) | LCS (Rural). | 55 households, 345 Individuals divided into groups by age and sex: | Females within the age of 6–15 and 16–50 had significantly higher exposure than their male counterparts. | |

| 0–5 years Females (n = 52) Males (n = 41) | 0–5 years Females: 1317 (1188)a Males: 1449 (1067)a | |||

| 6–15 years: Females (n = 61) Males (n = 48) | 6–15 years: Females: 2795 (2069)a Males: 1128 (638)a | |||

| 16–50 years: Females (n = 65) Males (n = 55) | 16–50 years Females: 4898 (3663)a Males: 1018 (984)a | |||

| >50 years: Females (n = 15) Males (n = 8) | >50 years Females: 2639 (2501)a Males: 2169 (977)a | |||

| Personal PM2.5 Exposure | ||||

| Titcombe and Simcik [43] (Tanzania) | CSS | Women Open firewood users (n = 3) charcoal users (n = 3) | Open firewood users: 1574 ± 287 μg/m3 Charcoal users: 588 ± 347 μg/m3 LPG users: 14 ng/m3 | Open firewood users were exposed to higher PM2.5 than charcoal users. |

| Dionisio et al. [49] (Gambia). | CSS (urban, peri-urban and rural areas) | Children under 5 years of age (n = 31) | 65 ± 41 μg/m3 | NR |

| Van Vliet et al. [45] (Ghana) | CSS. (Rural) | 29 households cooks (95% females) | 24-hour average PM2.5 Real time 208 (30–618) μg/m3 | Personal (Integrated) PM2.5 and Black carbon were higher for firewood users [(141.9 (112.5, 171.3)b; and (9.7 (8.4, 11.1)b, respectively], than Charcoal users [(44.6 (1.8, 87.4)b and (3.2 (0.6, 5.8)b, respectively]. |

| PM2.5 Integrated 128.5 (16.6–364.6) μg/m3 | ||||

| Black carbon 8.8 (1.9–18.2) μg/m3 | ||||

| Downward et al. [44] (Ethiopia) | CCSS (Urban) | Workers in biomass and electricity using bakeries (N = 15 workers per group) | PM2.5: Biomass bakers: 430 (2.0)c μg/m3 Electric bakers: 216 (2.2)c μg/m3 | Occupational exposure to biomass smoke in bakery; Number of stoves in use; Additional biomass usage in coffee brewing |

| Black Carbon: Biomass bakers: 67 (1.9)c μg/m3 Electric bakers: 15 (1.8)c μg/m3 | ||||

| Okello et al. [14] (Uganda) | CSS (Rural) | General Population (N = 102) divided into 6 age groups. Infants: (n = 17) Young Males: (n = 16) Young females: (n = 17) Adult males: (n = 17) Adult females: (n = 19) Elders: (n = 18) | Infants: 80.2 (1.34)c μg/m3 Young males: 26.3 (1.48)c μg/m3 Young females: 117.6 (1.49)c μg/m3 Adult males: 32.3 (1.97)c μg/m3 Adult females: 177.2 (1.61)c μg/m3 Elders: 63.9 (2.03)c μg/m3. | Women and girls had higher exposure to wood smoke than men and boys. |

| Personal CO Exposure | ||||

| Dionisio et al. [47] (Gambia). | CSS (urban, peri-urban and rural areas) | Children Under 5 years of age (N = 1181) | 1.04 ± 1.46 ppm | Rainy season Use of charcoal |

| Ochieng et al. [40] (Kenya) | CSS (Rural) | Women Traditional wood stove users: (n = 50) Improved wood stove users: (n = 50) | Traditional wood stove users: 5.12 ± 3.89 ppm Improved wood stove users: 3.72 ± 3.74 ppm | NR |

| Yamamoto et al. [48] (Burkina Faso) | CSS (semi-urban) | Women aged 15–45 years and children ≤9 years (N = 148) | Wood users: 3.3 (2.8-3.8)b ppm Charcoal users: 3.3 (2.8–3.7)b ppm | Cooking outdoors was negatively associated with personal CO levels (>2.5 ppm) |

| Quinn et al. [36] (Ghana) | CSS (Rural) | Pregnant women enrolled in GRAPHS who were primary cooks in households (n = 1183) | 1.6 (1.31) ppm (0.039–15.4 ppm) | NR |

| Quinn et al. [37] (Ghana) | RCT (Rural) | Pregnant women enrolled in GRAPHS who were primary cooks in households (N = 35). Randomized to: firewood (n =18) LPG (n =13) Biolite (n = 4) | Pre-intervention CO levels Firewood: 1.04 ppm LPG: 1.74 ppm Biolite: 1.43 ppm Post-intervention CO levels Firewood: 1.55 ppm LPG: 0.63 ppm Biolite: 1.45 | Only the LPG group showed a significant reduction in mean CO level following the intervention |

| Downward et al. [44] (Ethiopia) | CCSS | Workers in biomass and electricity using bakeries (N = 15 workers per group) | CO: Biomass bakers: 22 (2.4)d ppm Electric bakers: 1 (5.0)d ppm | Occupational exposure to biomass smoke in bakery; Number of stove in use; Additional biomass usage in coffee brewing were associated with higher exposure. |

| Yip et al. [41] (Kenya) | Cross-over study (Rural) | Women (N = 237) and children aged <5 years (n = 239) | All women: 1.3 (1.3, 1.4)d ppm TCS Women: 2.2 (1.7, 2.8)d ppm Children: 0.8 (0.7, 0.9)d ppm ICS Women:1.1 (1.0, 1.3)d ppm Children: 0.8 (0.7, 0.8)d ppm | There was a 44.9% reduction in mean personal CO level among women who crossed over to ICS |

| Okello et al. [14] (Uganda) | CSS (Rural) | General Population (N = 102) divided into 6 age groups. Infants: (n = 17) Young Males: (n = 16) Young females: (n = 17) Adult males: (n = 17) Adult females: (n = 19) Elders: (n = 18) | CO: Infants: 0.64 (2.12)d ppm Young males: 0.02 (3.67)d ppm Young females: 0.81 (3.83)d ppm Adult males: 0.17 (4.34)d ppm Adult females: 0.95 (3.26)d ppm Elders: 0.54 (3.07)d ppm | Women and girls had higher exposure to wood smoke than men and boys. |

| Carboxy- hemoglobin (COHb) | ||||

| Olujimi et al. [17] (Nigeria) | CCSS (Occupational exposure in a rural setting) | Charcoal workers and Non-Charcoal workers (n = 298 per group) | Carboxyhemoglobin: Charcoal workers: 13.28 ± 3.91 % (5.00–20.00%). Non-charcoal workers: 8.50 ± 3.68% (1.00–18.00%). | Working in a charcoal production site was associated with higher COHb level. |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) | ||||

| Titcombe and Simcik [43] (Tanzania) | CSS | Women Open firewood users (n = 3) charcoal users (n = 3) | Total PAH Open firewood users: 5040 ± 909 ng/m3 Charcoal users: 334 ± 57 ng/m3 LPG: <1 ng/m3 Benzo(a)pyrene Open firewood users: 767 ng/m3 Charcoal users: 44 ng/m3 LPG users: 0 ng/m3 | Open firewood users were exposed to higher PM2.5, PAH and benzo(a)pyrene than charcoal. |

| Awopeju et al. [38] (Ile-Ife, Nigeria) | CCSS (NS) | Women >20 years. Those who worked as street cooks for more than 6 months (n = 188); those who have never been street cooks (n = 197) | Benzene concentration in passive samplers worn by the women. Street cooks: 119.3 (82.7–343.7)e μg/m3 Non-street cooks: 0.0 (0.0–51.2)e μg/m3, p < 0.001). | Benzene concentration in passive samplers worn by the women street cooks was significantly higher that worn by the controls. |

| Olujimi et al. [18] (Nigeria) | CCSS (Occupational exposure in a rural setting) | Charcoal workers at two locations (Igbo-Ora: n = 25; Alabata: n = 20) and Non-Charcoal workers (n = 23) | Urinary1-Hydroxypyrene Charcoal workers: Igbo-Ora: 2.22 ± 1.27 μmol/mol creatinine Alabata:1.32 ± 0.65 μmol/mol creatinine Non-charcoal workers: 0.32 ± 0.26 μmol/mol creatinine | Working in a charcoal production site was associated with higher levels (>0.49 μmol/mol creatinine) of Urinary1-Hydroxypyrene. (RR: 3.14, 95% CI: 1.7–5.8, P < 0.01) |

[i] a = Mean (Variance); b = Mean (95% CI); c = Geometric mean (geometric standard deviation); d = Geometric mean (95% CI); e = median (inter-quartile range); CCSS = Comparative Cross-Sectional Study; CSS = Cross-sectional study; RCT = Randomized controlled trial; NR = Not Reported; GRAPHS = Ghana Randomized Air Pollution and Health Study; CO = Carbon monoxide; * = Personal PM10 exposure estimated from a 210, 14-hour days of continuous real-time monitoring of PM10 concentration and time-activity budget of the household members.

Table 2

Summary of epidemiological studies on health effects of wood smoke in sub-Saharan Africa.

| Reference (Country) | Design (Exposure setting) | Population (sample size) | Source of wood smoke (Comparison) | Method of Exposure assessment | Outcome(s) (Method of Assessment) | Health effect (Risk estimate) | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory outcomes | |||||||

| Ellegard [35] (Maputo Mozambique) | CSS (suburban) | Women who are household cooks (n = 1200) | Firewood and charcoal for domestic cooking (Electricity/LPG users) | Interview: principal fuel, defined as the fuel used most often to cook the main meal; measurement of personal PM10. | Cough, Dyspnea, Wheezing, Inhalation and exhalation difficulties (questionnaire); PEFR (mini-wright peak flow meter | Wood users had a significantly higher cough index (2.42 ± 0.104) and lower PEF rates (365 ± 3.4 L/min) than charcoal users (cough index: 1.77 ± 0.108; PEF rates: 382 ± 4.0 L/min) and users of modern fuels (cough index: 1.75 ± 0.198; PEF rates: 379 ± 7.4 L/min). There were no significant differences between the fuel user groups with respect to the non-cough respiratory symptom index. | 6 |

| Ezziati and Kammen [3334] (Laikipia, Kenya) | LCS (Rural) | 55 households made up of Infants (n = 93), Individuals aged 5–49 years (n = 229), Individuals aged >50 years (n = 23). | Firewood and charcoal for domestic cooking (PM10 ≤ 1000 vs. PM10 > 1000 μg/m3); (PM10 ≤ 200 vs. PM10 > 200 μg/m3). | Personal exposures to PM10 calculated from Indoor PM10 measurement data and time activity budget. | ARI, ALRI (WHO protocols for clinical diagnosis of ARI). | Risk of ARI and ALRI increased with higher PM10 exposure. For example, with reference to PM10 of <200, the adjusted odds ratio for ARI was 2·42 (1·53–3·83) in children <5 years with PM10 200–500. | 7 |

| Ibhazehiebo et al. [74] (Edo, Nigeria) | CSS (Rural and urban) | Women aged 20–70 years. Active wood users (n = 350); non-wood users (n = 300) | Wood use for cooking. (non-wood users) | Questionnaire: number of years of use of wood as cooking fuel; number of times of such cooking per day. | PEFR (mini-wright peak flow meter), Respiratory symptoms (cough with sputum production, dyspnea, wheezing, chest tightness and chest pain) | Respiratory symptoms were markedly elevated in the subjects compared to controls. Mean PEFR value for the wood users (289 ± 19.6 L/min) was significantly lower than non-wood users (364 ± 17.2 L/min), P < 0.05. PEFR decreased with increase in years of exposure to wood smoke. | 3 |

| Kilabuko et al. [51] (Bagamoyo, Tanzania) | CSS (Rural) | 100 households | Wood use for cooking. (Regular women cooks and children under age 5 Vs unexposed men and non-regular women cooks) | Observation; Kitchen, living room and outdoor measurement of PM10, CO and NO2. | ARI (questionnaire) | The risk of having ARI was higher for cooks and children under age 5 (exposed group) than the unexposed group (OR: 5.5; 95% CI: 3.6–8.5) | 3 |

| Fullerton et al. [57] Malawi | CSS (Rural and urban areas) | Adults (n = 374) | Firewood vs. Charcoal users | Questionnaire: type of biomass fuel used for cooking | Lung function (spirometry). | Wood users had significantly worse lung function than charcoal users {FEV1, ml: 2430 (670) Vs 2780 (680) P < 0.001; Percent predicted FEV1: 99 Vs 106, P < 0.008; FVC, ml: 3190 (830) Vs 3490 (870); FEV1/FVC ratio: 76.54 (9.11) Vs 79.80 (7.48) P = 0.001} for firewood and charcoal users, respectively. | 5 |

| Ekaru et al. [52] (Moi, Kenya) | Hospital-based CSS (NS) | Children Aged 0–5 years (n = 181) | Use of firewood/charcoal for domestic cooking (Use vs. non-use of firewood/charcoal) | Care-giver reported use of firewood and charcoal for cooking | Pneumonia (clinical diagnosis) | Use of firewood/charcoal were risk factors for mild pneumonia (OR 4.23, CI 3.9–4.6) and severe pneumonia (OR 1.1, CI 1.02–1.26). | 4 |

| Taylor and Nakai (Sierra Leone) | CSS (rural and peri-urban) | Women aged 15–45 years (n = 520); children under 5 years of age (n = 520). | Use of firewood/charcoal for domestic cooking (Wood vs. Charcoal use) | Questionnaire: Type of biomass fuel normally used for cooking | ARI (interview: cough and rapid breath in the last 2 weeks preceding study as proxy for ARI) | Relative to charcoal use, wood use was associated with ARI in children but not in women (adjusted OR = 2.03, 95%CI: 1.31–3.13) and (adjusted OR = 1.14, 95%CI: 0.71–1.82), respectively. ARI prevalence was higher for children in homes with wood stoves (64%) compared with homes with charcoal stoves (44%). | 4 |

| Oloyede et al. [58] (Nigeria) | Comparative CSS (NS) | Children aged 6–16 years. Those living in fishing port (n = 358) and those living in farm settlements (n = 400) | Firewood use in fish drying (Residence vs. Non-residence in fishing port) | Observation: Living in fishing port | Lung function (spirometry). | Children living in fishing port had reduced lung function (FVC: 1.32 ± 0.67; FEV1: 1.22 ± 0.62) compared with those living in farm settlements (FVC: 1.45 ± 0.43; FEV1: 1.41 ± 0.41. Decline in lung function was associated with increase in duration of exposure to fish drying. | 5 |

| Ibhafidon et al. [59] (Ile-Ife, Nigeria) | CSS (NS) | Male and female Individuals including firewood users (n = 35), kerosene users (n = 34) and LPG users (n = 21). | Firewood for cooking (firewood vs. LPG users) | Modified BMRC questionnaire: predominant cooking fuel | Respiratory symptoms (Modified BMRC questionnaire); lung function (spirometry). | Firewood users reported more respiratory symptoms, compared with LPG users. 95.2% of LPG users had normal lung function (FEV1/FVC > 0.7 and predicted FEV1 of at least 80%), 71.4% of firewood users, respectively. | 4 |

| Sanya et al. [56] (Kampala, Uganda) | Case. Control study (NS) | Asthma patients aged >13 years. Those with exacerbations (n = 43); Those without exacerbations (n = 43) | Wood and charcoal use for cooking (in-house vs. no in-house wood/charcoal stoves) | Questionnaire: use of in-house wood/charcoal stoves | Asthma exacerbations (clinical assessment) | In-house wood/charcoal use was not associated with increased risk of asthma exacerbations (OR = 0.882, 95% CI: 0.329–2.36, P = 0.802) | 4 |

| Umoh and Peters [20] (Akwa-Ibom, Nigeria) | CCSS (Rural) | Women involved in fish- smoking activities (n = 324) and women involved in fishing but not fish smoking (n = 346) | Wood use in fish smoking (Fish-smokers vs. non fish-smokers) | BMRC Respiratory disease Questionnaire: based report of involvement Fish-smoking | Lung function (spirometry) | Fish smokers had lower lung function (Mean FEV1/FVC = 68.8 ± 15.3 %) than non-fish smokers (FEV1/FVC = 78.3 ± 9.6 %), P < 0.001. | 5 |

| Ngahane et al. [60] (Bafoussam, Cameroon) | CSS (Semi-rural) | Women >40 years. Those using wood (n = 145) and those using other fuel sources (n = 155) for cooking. | Wood for domestic cooking (wood vs. other fuel [charcoal, gas, electricity] users) | Questionnaire-based report of cooking fuel. | Lung function (spirometry) Respiratory symptoms (questionnaire) | Use of wood as a cooking fuel was associated with impairment of lung function (Adjusted mean difference in FEV1= –120; 95% CI: –205, –35; P = 0.005). Prevalence of chronic bronchitis was higher (7.6%) in wood smoke group than the other fuels (0.6%). | 3 |

| Dienye et al. [50] (Rivers State, Nigeria) | CCSS (rural) | Women age ≥15 years. Those involved in fish smoking (n = 210) and those not involved in fish smoking (n = 210) | Wood use for fish smoking (involvement vs. non-involvement in fish smoking) | Self-reported involvement in fish smoking | Respiratory symptoms (questionnaire). PEFR (mini-wright peak flow meter). | Fish smoking was associated with increased risk of sneezing (OR = 2.49, 95% CI: 1.62–3.82; P < 0.001), catarrh (OR = 3.77; 95% CI: 2.44–5.85, P < 0.001), cough (OR = 3.38, 95% CI: 2.22–5.15, P < 0.001) and chest pain (OR = 6.45, 95% CI: 3.22–13.15, P < 0.001). The mean PEFR of 321 ± 58.93 L/min among the fish smokers was significantly lower than 400 ± 42.92 L/min among the controls (p = 0.0001). | 4 |

| PrayGod et al. [54] (Mwanza, Tanzania) | Case-control (NS) | Children. Under 5 years Cases (n = 45), controls (n = 72). | Firewood and charcoal (Firewood/charcoal users vs. Gas/Electricity users); (indoor vs outdoor cooking). | Questionnaire: Source of cooking fuel; location of cook stove. | Clinical/Laboratory diagnosis of pneumonia | Firewood and charcoal use were not associated with increased risk of pneumonia (Unadjusted OR = 2.1; 95% CI: 0.2–27 and OR = 1.9 95% CI: 0.2–18, respectively). An increased risk of severe pneumonia was associated with cooking indoors (OR = 5.5, 95% CI: 1.4–22.1) | 5 |

| Awopeju et al. [38] (Ile-Ife, Nigeria) | CCSS (NS) | Women >20 years. Those who worked as street cooks for more than 6 months (n = 188); those who have never been street cooks (n = 197) | Firewood and charcoal for street cooking (street cooks vs. Non-street cooks. | Questionnaire: number of hour-years of exposure to street cooking; hours spent cooking daily with biomass fuel at home. Quantification of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in a sub-sample of the women. | Respiratory symptoms (Questionnaire); pulmonary function (spirometry) | The odds of reported cough (adjusted OR: 4.4, 95% CI: 2.2–8.5), phlegm (AOR: 3.9, 95% CI: 1.5–7.3) and airway obstruction, FEV1/FVC < 0.7 (adjusted OR of 3.3 (95% CI 1.3 to 8.7) were significantly higher among the street cooks than controls. | 5 |

| North et al. [61] (Rural Uganda) | Prospective cohort study (Rural) | HIV-infected adults aged >18 years (N = 734; 223 males 511 females) | Use of Firewood/charcoal for domestic cooking. (Firewood Vs Charcoal) | Interview: main cooking fuel | cough of ≥4 weeks duration (self-report). | Cooking with firewood was associated with increased risk of chronic cough among females (adjusted OR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.00–1.99; p = 0.047). | 3 |

| Okwor et al. [21] (Ogun, Nigeria) | CCSS (Rural) | Females aged 13–60 years in two occupations: garri processors (n = 264) and petty traders (n = 264). | Firewood use in garri processing (occupational exposure vs. non-exposure to wood smoke; ≥10years vs <10 years of occupational exposure. | Observation: Working in garri production site | Respiratory symptoms (self-report); pulmonary function (spirometry). | Prevalence of obstructive pulmonary defect (FEV1/FVC < 70%) among the cassava processors was 21.3% compared to 6.4% among petty traders (P < 0.001). Occupational biomass (wood) fuel use (OR = 6.101, 95% CI 3.212–11.590) and working as a cassava processor for ≥ 10 years (OR 14.916, CI 5.077–43.820) were associated with increased risk of obstructive pulmonary defect). | 4 |

| Tazinya et al. [55] (Bameda, Cameroon) | CSS (NS) | Children under 5 years of age (n = 512) | Exposure to firewood smoke >30 minutes/day. non-exposure to firewood smoke | Questionnaire: Exposure to firewood smoke | ARI (WHO guideline for diagnosis management of pneumonia in children | Exposure to wood smoke was associated with ARI (adjusted OR: 1.85, 95% CI: 1.22–2.78). | 5 |

| Cardiovascular outcomes | |||||||

| Alexander et al. [62]a. (Ibadan, Nigeria) | RCT (Peri-urban) | Pregnant women (N = 108; randomized to firewood (n = 51); randomized to ethanol (n = 58) | Firewood use in domestic cooking (Firewood vs. Ethanol). | Interview: primary cooking fuel | Blood pressure (standard method). | There was no statistical difference in DBP (model 1: χ25 = 5.24; P = 0.39; model 2: χ23 = 2:09; P = 0.55) and SBP pressure (model 1: χ25 = 4.69; P = 0.45; model 2: χ23 = 3.44; P = 0.33) between the women randomized to firewood and those randomized to ethanol. | 4 |

| Quinn et al. [36] (Ghana) | CSS (rural) | Pregnant women enrolled in GRAPHS (n = 817) | Firewood and charcoal use in domestic cooking (1 ppm increase in CO exposure) | 72-hour personal CO monitoring | Blood pressure (watch automatic BP monitor). | CO exposure was significantly associated with diastolic blood pressure (each 1ppm increase in exposure to CO was associated with 0.43 mmHg higher DBP [95% CI: 0.01, 0.86] and 0.39 mmHg higher SBP (95% CI: –0.12, 0.90). | 7 |

| Quinn et al. [37] (Ghana) | RCT (rural) | Non- Pregnant women enrolled in GRAPHS (N = 44). Randomized to firewood (n =23), Improved biomass stove (n = 5) and LPG (n =16) | Firewood for domestic cooking. (Firewood vs. Improved biomass stove and LPG) | Observation: use of firewood, improved biomass stoves or LPG stoves for cooking; Personal 72-hour CO exposure monitoring | Ambulatory blood pressure measurement (ABPM) | ABPM revealed that peak CO exposure (defined as ≥4.1 ppm) in the 2 hours prior to BP measurement was associated with elevations in hourly systolic BP (4.3 mmHg [95% CI: 1.1, 7.4]) and diastolic BP (4.5 mmHg [95% CI: 1.9, 7.2]), as compared to BP following lower CO exposures. Use of improved cookstoves was not significantly associated with lower post-intervention SBP and DBP (within-subject change in SBP and DBP of –2.1 mmHg, 95% CI: -6.6, 2.4 and –0.1, 95% CI: –3.2, 3.0, respectively). | 7 |

| Ofori et al. [63] (Rivers State, Nigeria) | CSS (rural) | Women aged 18 and above (n = 389) | Firewood and charcoal (BMF vs. non-BMF) | Questionnaire: predominant cooking fuel | Blood pressure, lipid profile, carotid intima media thickness (all were measured using standard protocols). | Use of BMF was significantly associated with 2.7mmHg higher systolic blood pressure (p = 0.04), 0.04mm higher CIMT (P = 0.048), increased odds of pre-hypertension (OR:1.67, 95% CI: 1.56, 4.99, P = 0.035), but not hypertension OR: 1.23, 95% CI: 0.73, 2.07, P = 0.440) | 5 |

| Reproductive outcomes | |||||||

| Amegah et al. [64] Ghana | CSS (urban) | Mothers and their new born | Charcoal use in domestic cooking. (Charcoal vs. LPG) | Questionnaire: type of cooking fuel used | Birth weight (from hospital records); low birth weight (birth weight ≤2500g) | Exposure to charcoal was associated with reduction in birth weight (adjusted β: –381, 95% CI: –523, –239 and –278, 95% CI: –425, –131 p = 0.000) for all births and term births, respectively. Exposure to charcoal smoke was also associated with increased risk of low birth weight in all births (adjusted RR: 2.41, 95% CI: 1.34, 4.35, P = 0.003), but not term births (adjusted RR: 1.79, 95% CI: 0.81, 3.94, P = 0.112) | 6 |

| Demelash et al. [66] (Ethiopia) | CCS (rural and urban) | Mothers with singleton live birth. Cases: those who gave live births weighing less than 2500g, n =136) controls (those who gave live births weighed more than 2500g (n = 272). | Firewood use in domestic cooking. (Firewood vs. Electricity) | Questionnaire: type of energy used for cooking | Low birth weight (birth weight ≤2500g). | Use of firewood for cooking was associated with low birth weight (Adjusted OR: 2.7; (95% CI:1.00–7.17) | 5 |

| Whitworth et al. [67] (South Africa) | CSS (rural) | Women (n = 420 | Firewood use in domestic cooking. (Open wood fires vs. Electricity) | Questionnaire: type of cooking fuel mainly used. | Plasma concentrations of anti-Müllerian hormone (ELISA Method) | Compared with women who used an electric stove, no association was observed among women who cooked indoors over open wood fires (Adjusted β: –3, 95% CI: –22, 21 and –9, 95% CI: –24, 9 for outdoor wood users and indoor wood users, respectively). | 5 |

| Amegah et al. [65] Ghana | CSS (urban and rural) | Women aged 15–49 years (n = 7183) | Use of Biomass fuel (charcoal, firewood and straw/shrubs/grass) for domestic cooking. (biomass fuel vs. Non-biomass fuel (electricity, LPG and natural gas) | Questionnaire: type of fuel used by households for cooking. | Lifetime experience of stillbirth (questionnaire). | Biomass fuel use mediated 17.7% of the observed effects of low maternal educational attainment on lifetime stillbirth risk | 3 |

| Cancer outcomes | |||||||

| Patel et al. [68] (Kenya) | CCS (NS) | Cases: patients with oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (n = 159); Controls: Healthy individuals without oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (n = 159). | Firewood and charcoal use in domestic cooking. [Other fuels (kerosene electricity LPG)] | Questionnaire: type of cooking fuel | Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (histological diagnosis) | Cooking with firewood or charcoal was independently associated with Oesophageal cancer (OR: 2.32, 95% CI: 1.41–3.84) | 4 |

| Kayamba et al. [69] (Lusaka, Zambia) | CCS (Rural and urban) | Cases: patients with oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (n = 77); Controls: Healthy individuals without oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (n = 145). | Firewood and charcoal use in domestic cooking. (non-use of Firewood/charcoal) | Questionnaire: type of cooking fuel | Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (histological diagnosis) | Cooking with firewood or charcoal increased the risk of developing Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (adjusted odds ratio: 3.5, 95% CI: 1.4–9.3) | 5 |

| Mlombe et al. [70] Malawi | CCS (NS) | Cases: Adult patients with oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (n = 96); Controls: Healthy individuals without oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (n = 180). | Firewood/charcoal use in domestic cooking. (Firewood vs. Charcoal) | Questionnaire: type of cooking fuel | Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (histological diagnosis) | The odds of oesophageal cancer were 12.6 times higher among those who used firewood compared to those who used charcoal (Adjusted OR: 12.6, 95% CI: 4.2–37.7). | 5 |

| Other health outcomes | |||||||

| Das et al. [73] (Malawi) | CSS (Rural and urban) | Household cooks (n = 655) | Use of firewood, charcoal and crop residue for domestic cooking. (Firewood or crop residue vs. Charcoal) | Interview: cooking technologies and fuels used. | Five categories of health outcomes: cardiopulmonary, respiratory, neurologic, eye health, and burns. (questionnaire). | Use of low quality firewood or crop residue was associated with significantly higher odds of shortness of breath at rest (Adjusted OR: 1.02; 95% CI: 0.24–4.32 and 6.22; 95% CI: 1.13–34.17, respectively), chest pains (Adjusted OR: 3.00; 95% CI: 0.91–9.86 and 4.46; 95% CI: 0.92–21.66, respectively), night phlegm (Adjusted OR: 5.39; 95% CI: 1.06–27.45 and 11.59; 95% CI: 1.38–97.31, respectively), forgetfulness (Adjusted OR: 4.48; 95% CI: 1.42–14.19 and 9.13; 95% CI: 1.86–44.95, respectively) and dry irritated eyes (Adjusted OR: 1.64; 95% CI: 0.54–4.99 and 3.75; 95% CI: 0.81–36, respectively). | 4 |

| Owili et al. [39] (23 Countries in SSA) | CSS | Children under 5 years of age (n = 783,691) | Use of Charcoal as cooking fuel. (Charcoal vs. Clean fuels [electricity, natural gas, biogas or liquefied petroleum gas]). | Questionnaire: type of cooking fuel | All-cause under-five mortality | Use of charcoal as cooking fuel was significantly associated with the risk of under-five mortality in SSA before and after controlling for other indicators. (Crude HR: 1.97, 95% CI: 1.80, 2.16; Adjusted HR: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.10, 1.34). | 3 |

| Belachew et al. [72] Ethiopia | CSS (NS) | The entire population mate (N = 3405); male: 1567 Female: 1838 | Use of charcoal for domestic cooking. (Charcoal use vs. No charcoal use) | Questionnaire/observation: charcoal use for cooking | Sick-building syndrome (questionnaire) | Sick-building syndrome was significantly associated with charcoal use as cooking energy source (Adjusted OR: 1.4, 95% CI: 1.02–1.91) | 3 |

| Mbuyi-Musanzayi et al. [71] (Lubumbashi, Congo) | CCS (NS) | Cases: New born with Non-syndromic cleft lip and/or cleft palate (n = 162) Controls: clinically normal newborn (n = 162) | Use of Charcoal as cooking fuel. (Indoor Vs No indoor cooking with charcoal) | Questionnaire: inhouse cooking with charcoal (yes or no) | Non-syndromic cleft lip and/or cleft palate (clinical diagnosis) | Indoor cooking with charcoal was significantly associated with non-syndromic cleft lip and/or cleft palate (OR = 6.536, 95% CI: 1.229, 34.48. p = 0.0001) | 3 |

[i] CSS = Cross-sectional study; CCSS = Comparative cross-sectional study; LCS = Longitudinal cohort study; CCS = Case-control study; RCT = Randomized controlled trial; NS = Not stated; ISAAC = International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood; BMRD = British Medical Research Council; PEFR = Peak Expiratory Flow Rate; GRAPHS = Ghana Randomized Air Pollution and Health Study; a = only data for baseline firewood users were included in this review.