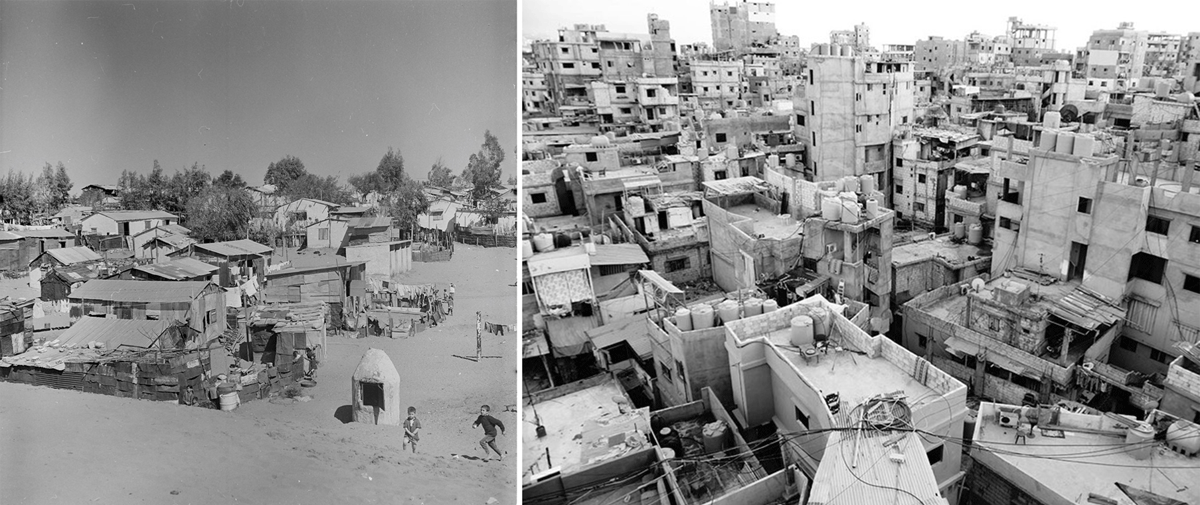

Figure 1

Early photograph (left) of Burj el Barajneh camp in 1950s Lebanon, showing a humanitarian scale embodied in UN plots of 96–100 m2 each; more recent photo from 2016 (right) showing the ‘political-scale’ that has emerged over protracted displacement [Courtesy of author + UNRWA-ICIP Archives].

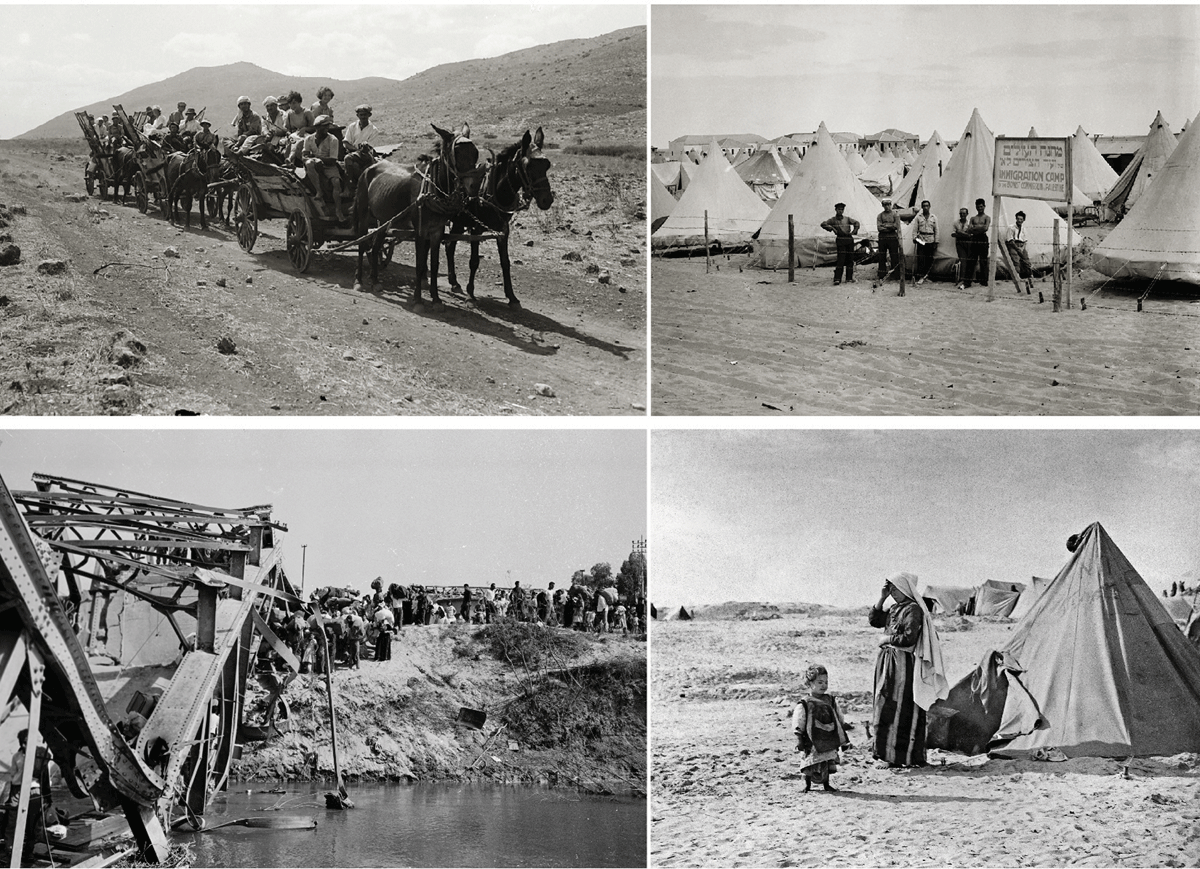

Figure 2

The top images show incoming Jewish settlers to Palestine and the ‘immigration’ camps produced for them, while the lower images show the violent expulsion of the Palestinian people (crossing the Allenby Bridge into Jordan) and the refugee camps set up to absorb their mass displacement [Courtesy of https://unitedstateofisrael.blogspot.com + UNRWA-ICIP Archives].

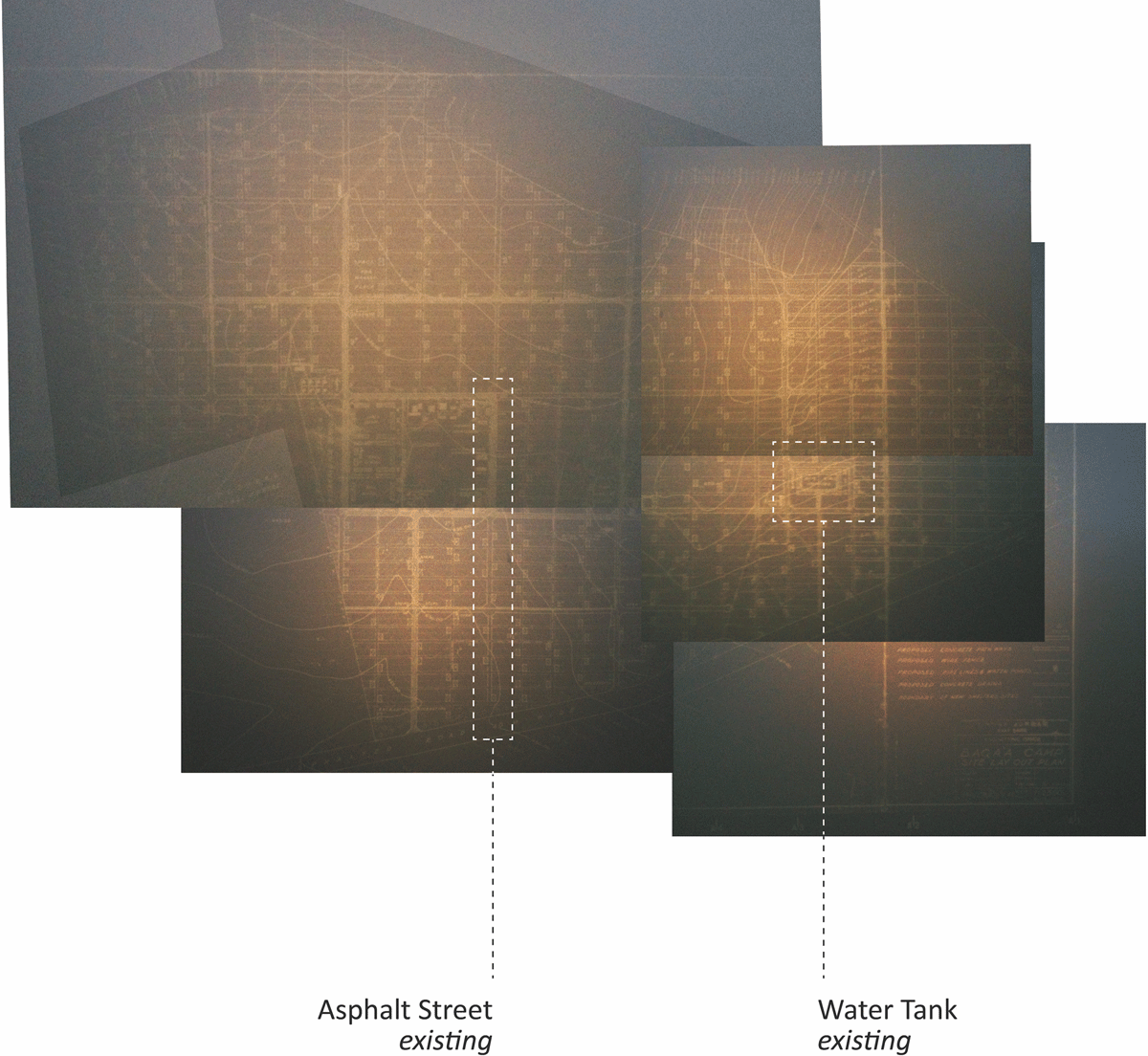

Figure 3

Photograph of a map of Baqa’a camp as drawn up at the United Nations’ headquarters in Vienna, dated 1969. On the right is the large concrete water-tank which existed on the site when refugees first arrived [Courtesy of UNRWA-ICIP Archives].

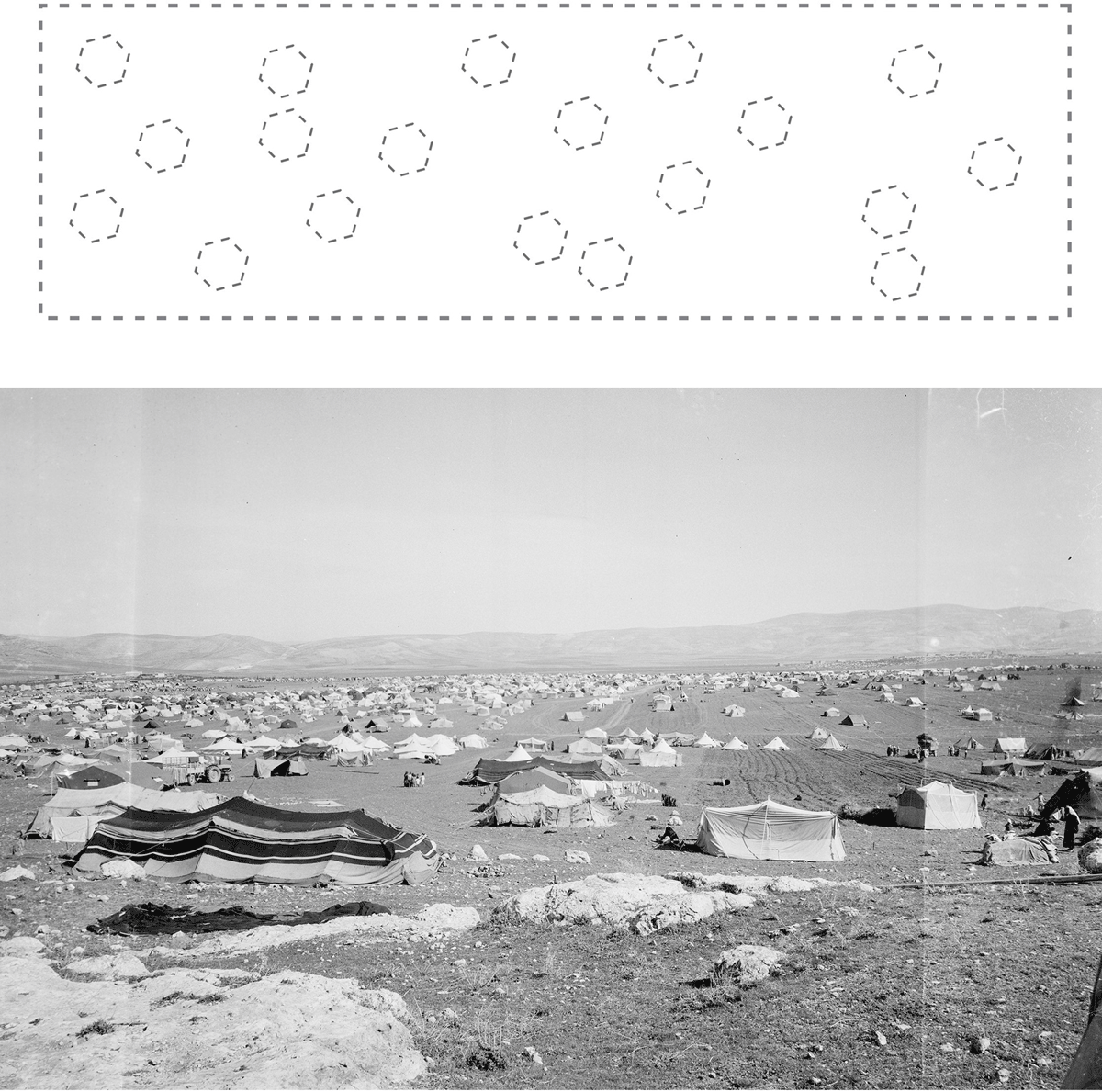

Figure 4

Photograph/diagram of the 1948 camp layout in Baqa’a showing a haphazard layout of tents that corresponds to previously arranged refugee groups along a kinship or village basis [Courtesy of UNRWA-ICIP Archives + drawing by the author].

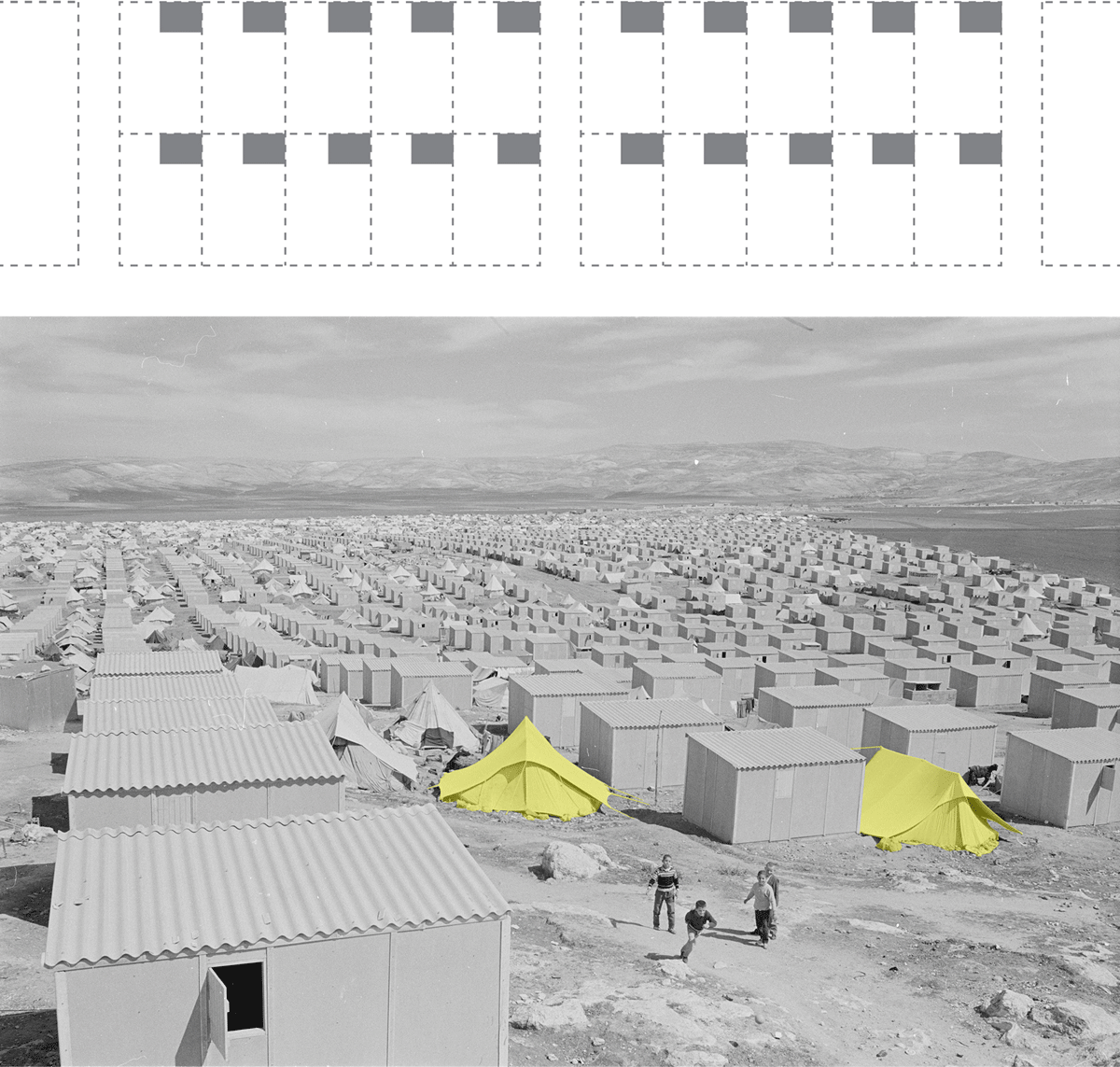

Figure 5

Photograph/diagram of the 1950s camp layout in Baqa’a showing UNRWA’s grid layout of 96–100 m2 plots, and with each plot having a 12 m2 prefabricated room for the family to live in [Courtesy of UNRWA-ICIP Archives + drawing by the author].

Figure 6

Photograph showing various materials that refugees incorporated when erecting the facades of their shelters inside Burj el Barajneh camp, such as fabrics and zinc sheets to conceal the concrete walls being built behind [Courtesy of UNRWA-ICIP Archives].

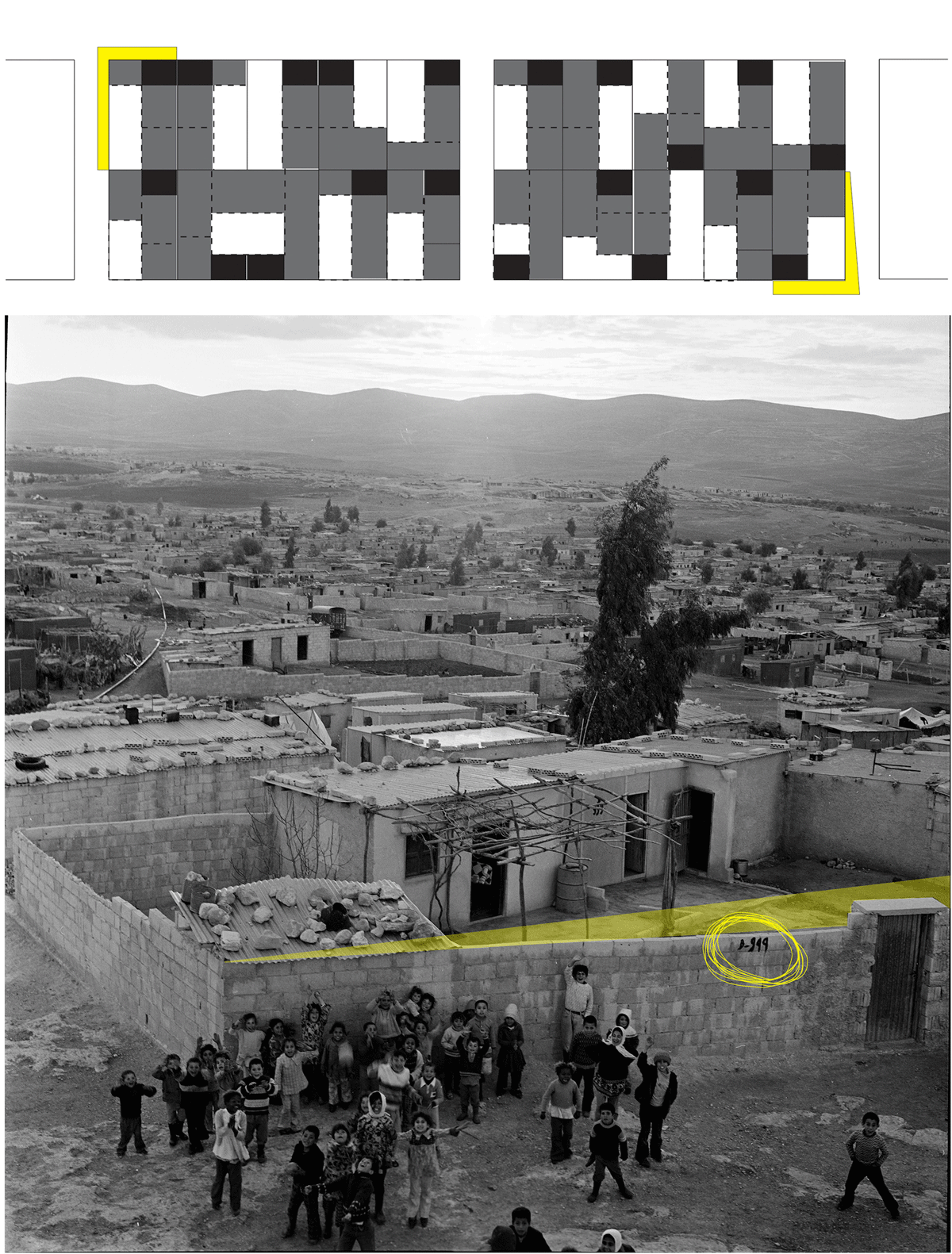

Figure 7

Photograph/diagram of the 1960s camp layout in Baqa’a showing the first material additions inside the UNRWA plots to provide internal amenities for refugee families, and the re-alignment of plots as acts of ‘spatial violations’ [Courtesy of UNRWA-ICIP Archives + drawing by the author].

Figure 8

Photograph/diagram of the 1970s camp layout in Baqa’a showing that most refugee plots were now filled with concrete rooms, and thus concrete had started to overflow outside the plots in the form of Attabat (‘doorsteps’) which kept out muddy water and served as outdoor social spaces [Courtesy of UNRWA-ICIP Archives + drawing by the author].

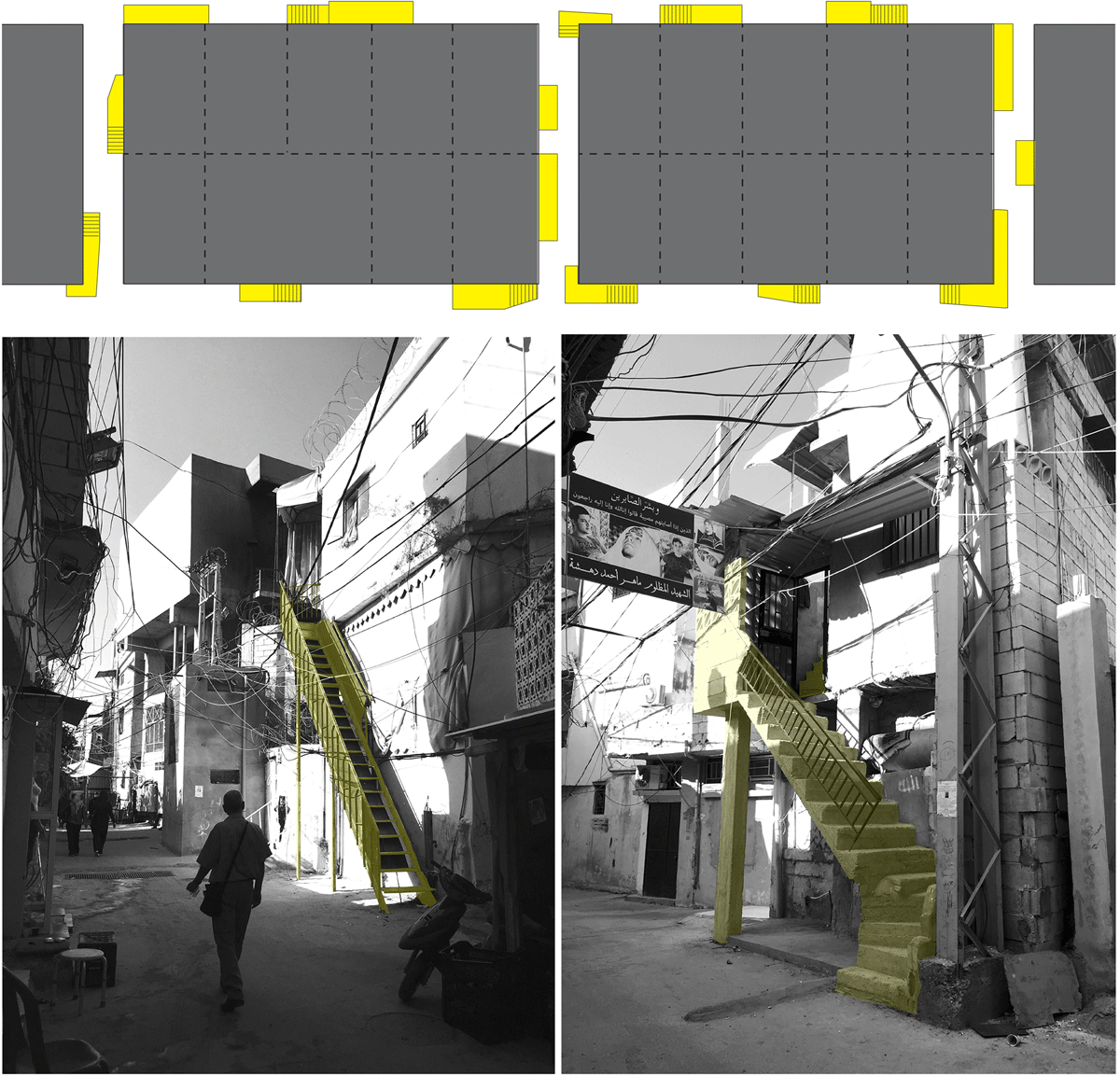

Figure 9

Photograph/diagram of the 1980s–90s camp layout in Baqa’a which, with the horizontal plane now saturated, the refugees adopted architectural elements to allow for vertical expansion. Light metal stairs (left) gradually morphed into solid, concrete stairs (right) [Courtesy of UNRWA-ICIP Archives + drawing by the author].

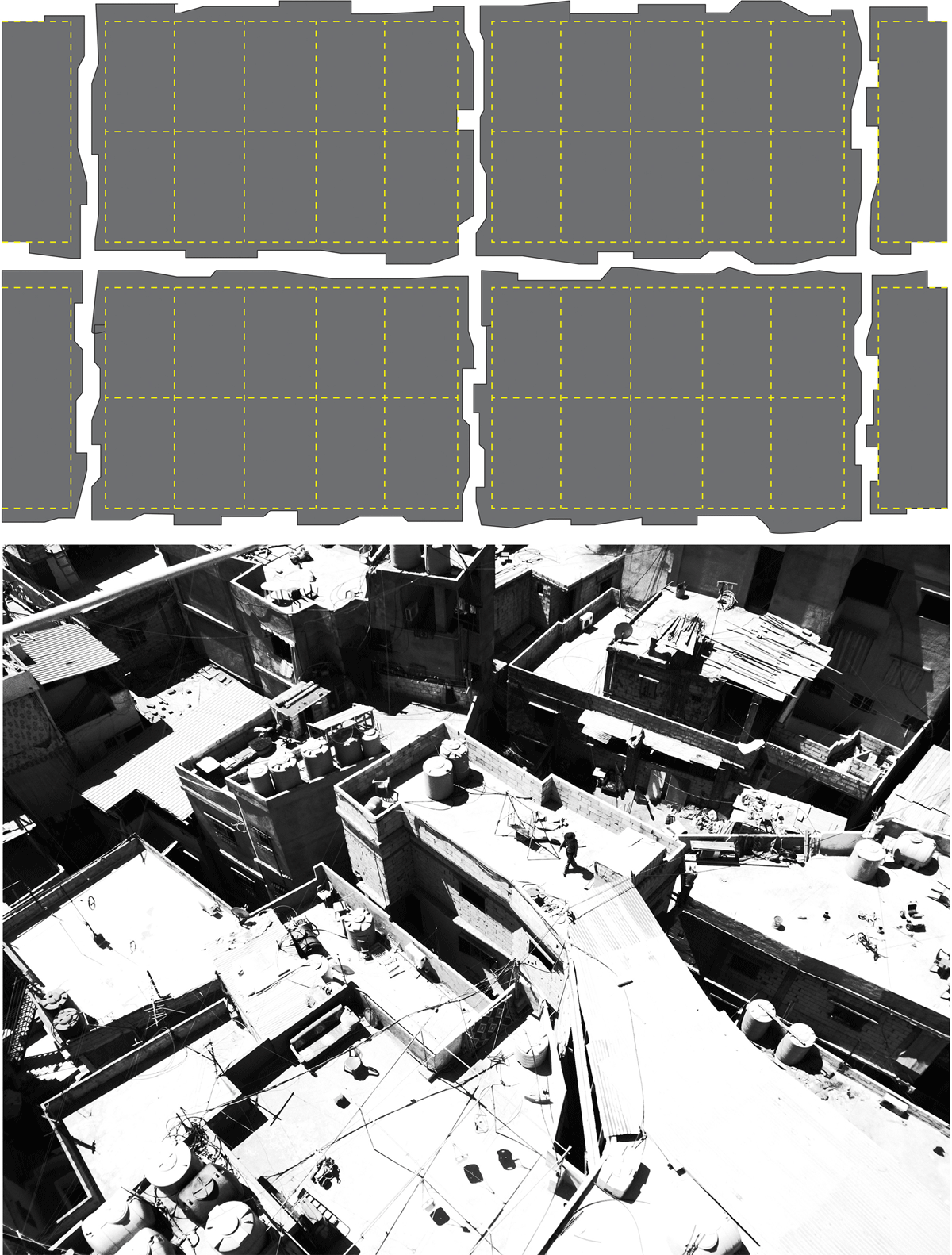

Figure 10

Photograph/diagram of today’s camp layout in Baqa’a, showing that it has now become a ‘Palestinian-political’ space in that it facilitates a spatial economy beyond the residents’ economic and social means [Courtesy of the author].

Figure 11

The shelter shown in the photograph at the top has the words ‘For Sale’ inscribed on its walls, whereas the writing on the lower shelter states: ‘This house is not for sale. No to settlement’ [Courtesy of the author].

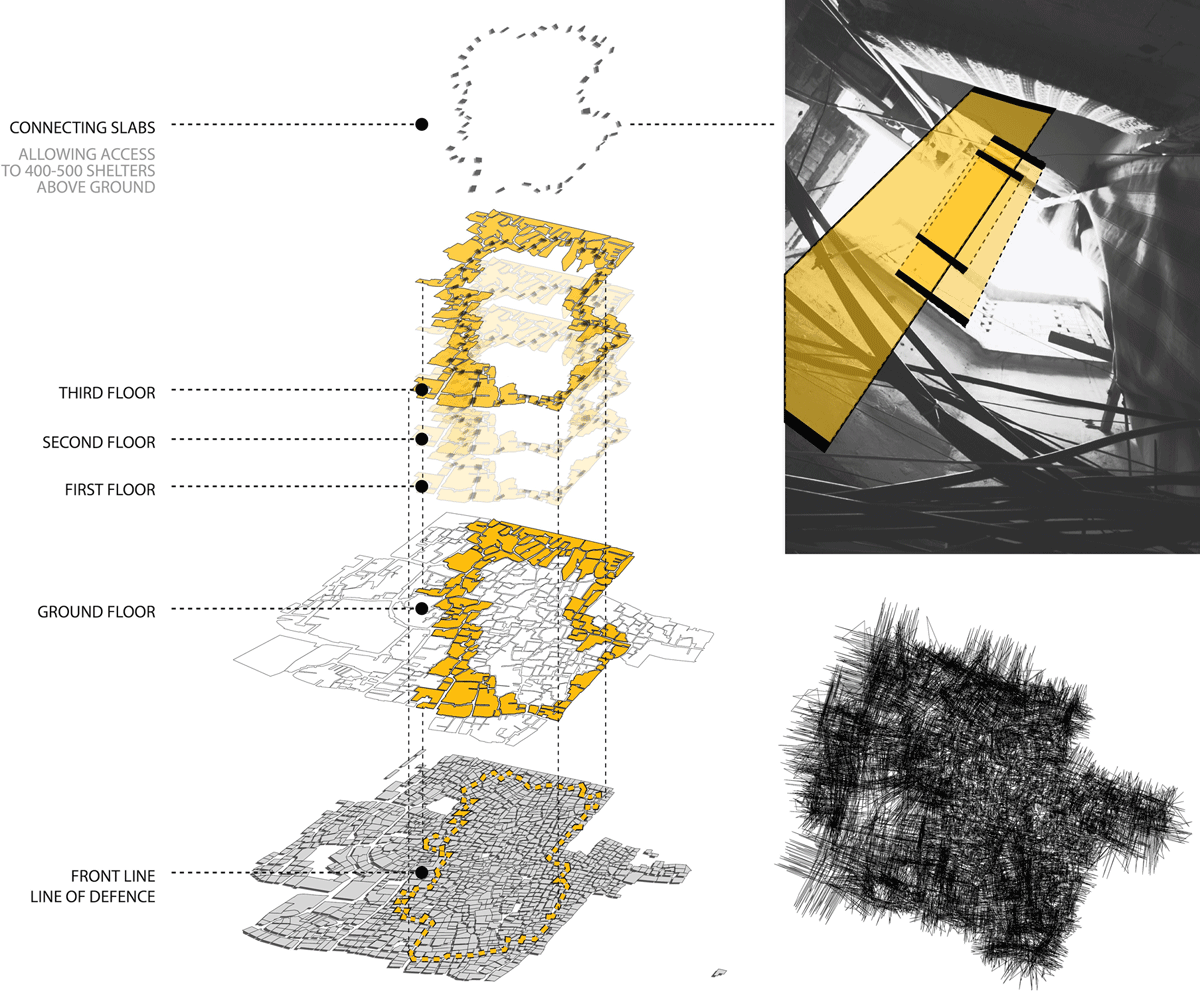

Figure 12

Plan showing the ‘elevated walkways’ inside Burj el Barajneh camp built in disregard of UN demarcations, thus creating a ‘political-scale’ as a spatial tactic which enabled multiple levels of movement of fighters during the ‘War of the Camps’ [Drawing by the author].

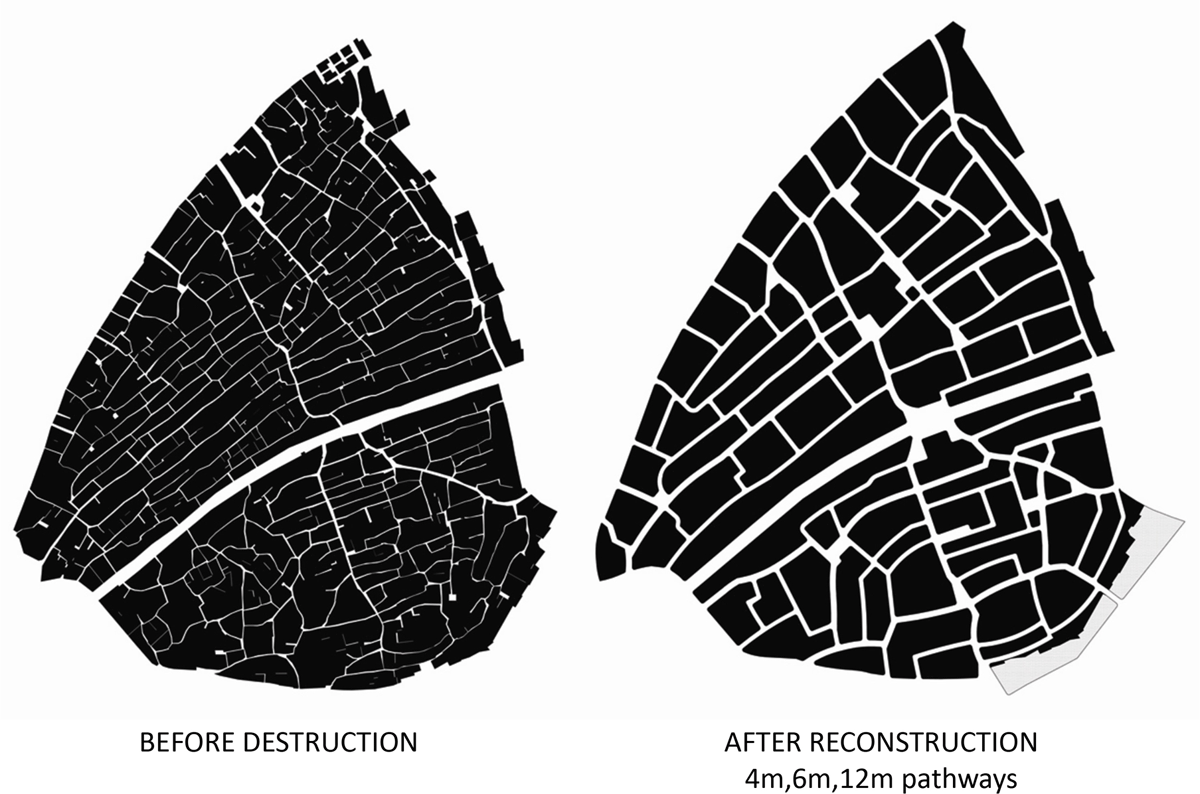

Figure 13

Reconstruction of Nahr el Bared camp showing the old scale before destruction (left) and the new scale (right) as demanded by the Lebanese government [Courtesy of UNRWA-ICIP Archives].

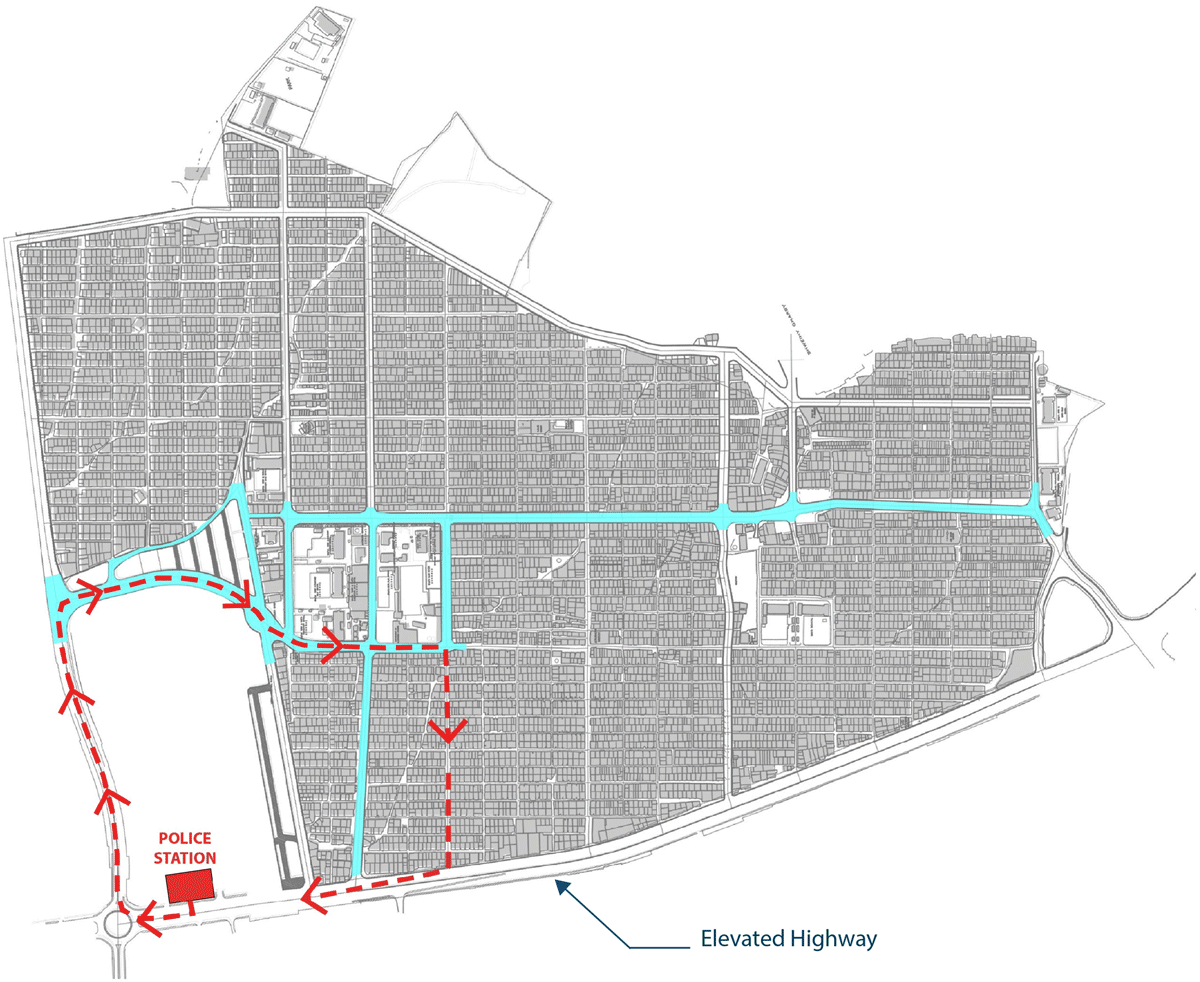

Figure 14

Map showing the newly opened streets (in blue) in Baqa’a camp, Jordan to creating wider roads for the rapid entry of tanks into the heart of the camp [Drawing by the author].

Figure 15

Photographs showing the 4-metre ‘tension space’ maintained by the Jordanian gendarmes and the refugees inside the camp and (bottom) showing entry of tanks into the heart of the camp enabled by the created wider roads [Courtesy of the author].

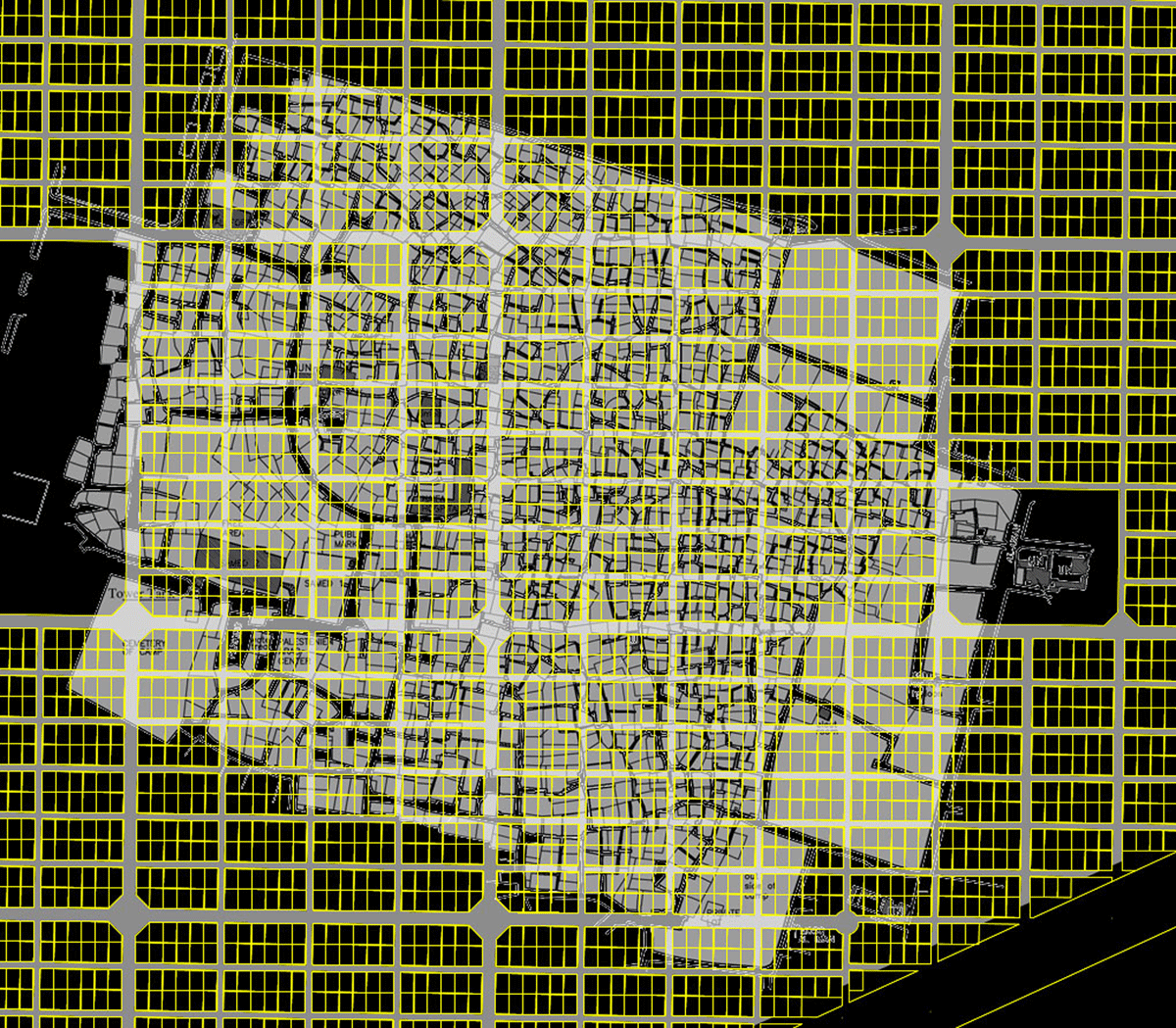

Figure 16

The superimposition in the ‘Space of Refuge’ exhibition of the two different camp-scales of Baqa’a (in yellow) and Burj el Barajneh (in grey) reveals that the former’s original ‘relief-scale’ still largely pertains, due to the Jordanian government’s strong control over space, whereas the opposite condition exists in Burj el Barajneh camp, with what is now multiple encroachments and an intense use of space [Drawing by the author].

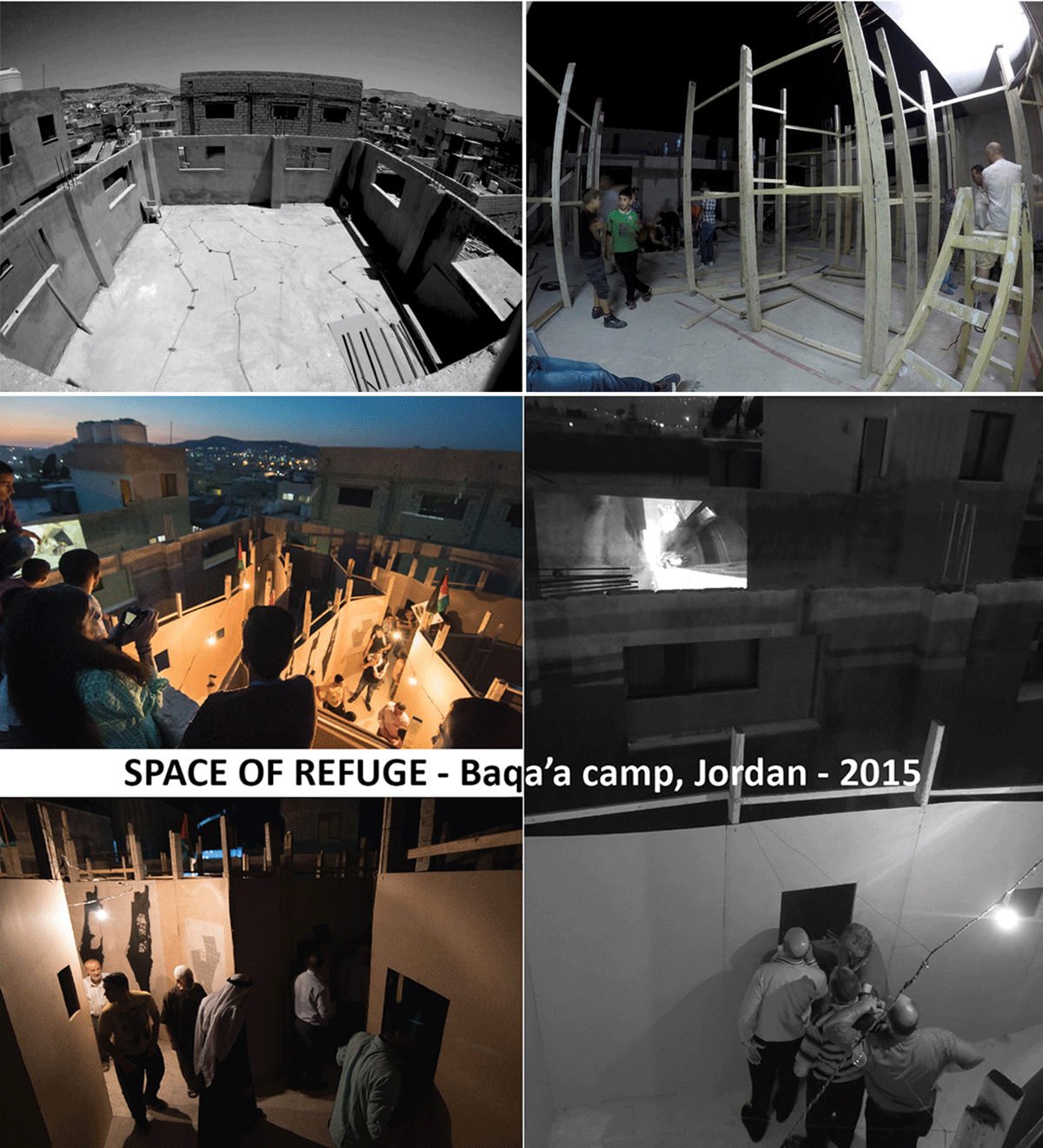

Figure 17

Photographs of the ‘Space of Refuge’ exhibition in Baqa’a camp in 2015, showing the superimposition of the Burj el Barajneh camp-scale and residents roaming the installation while viewing projected films of the spatialities of other camps [Courtesy of the author and Ronan Glynn].

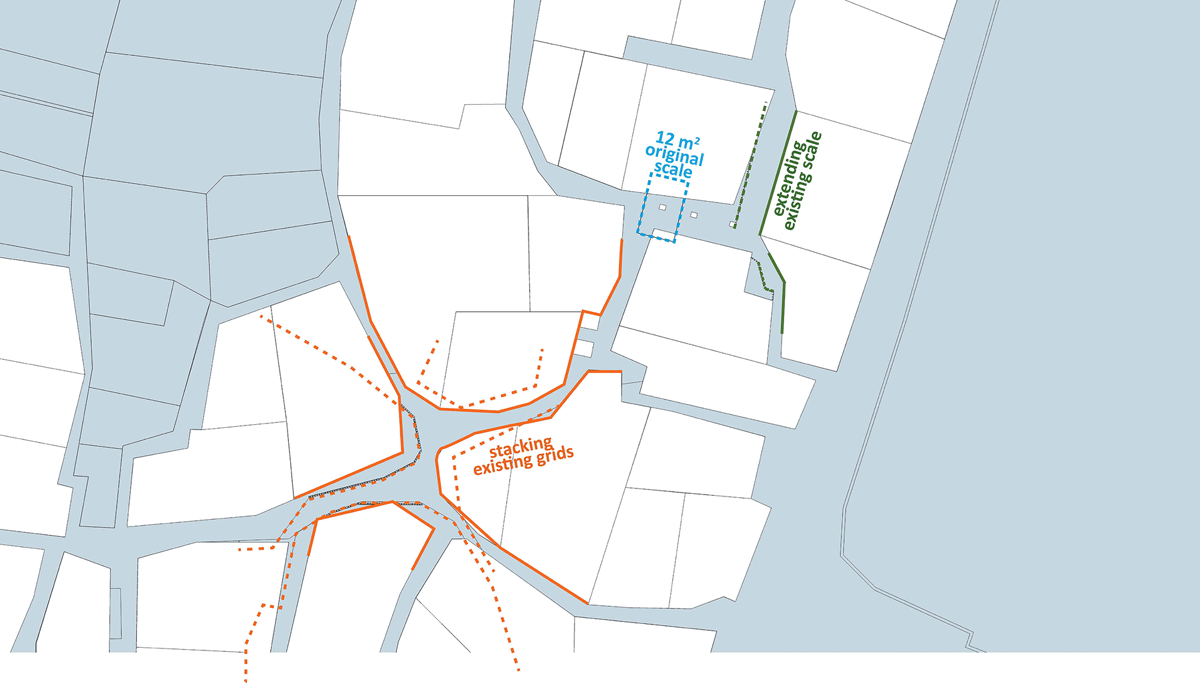

Figure 18

Map of the ‘Space of Refuge’ exhibition in Burj el Barajneh camp in 2016, indicating the installation site in Sa’iqa Square and the various superimposed scales [Drawing by the author].

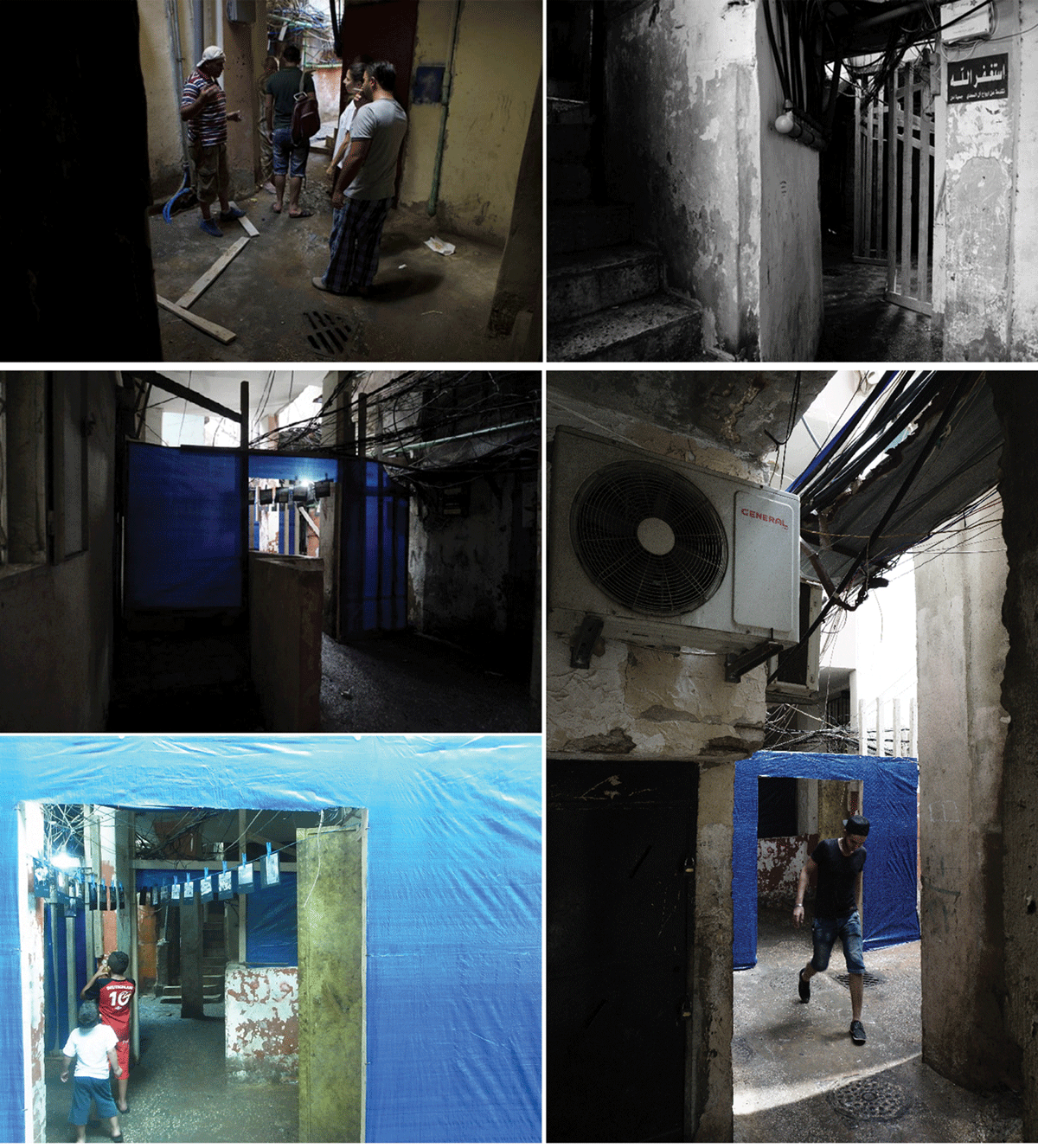

Figure 19

Photographs of the ‘Space of Refuge’ exhibition being built when it was moved to Burj el Barajneh [Courtesy of the author].

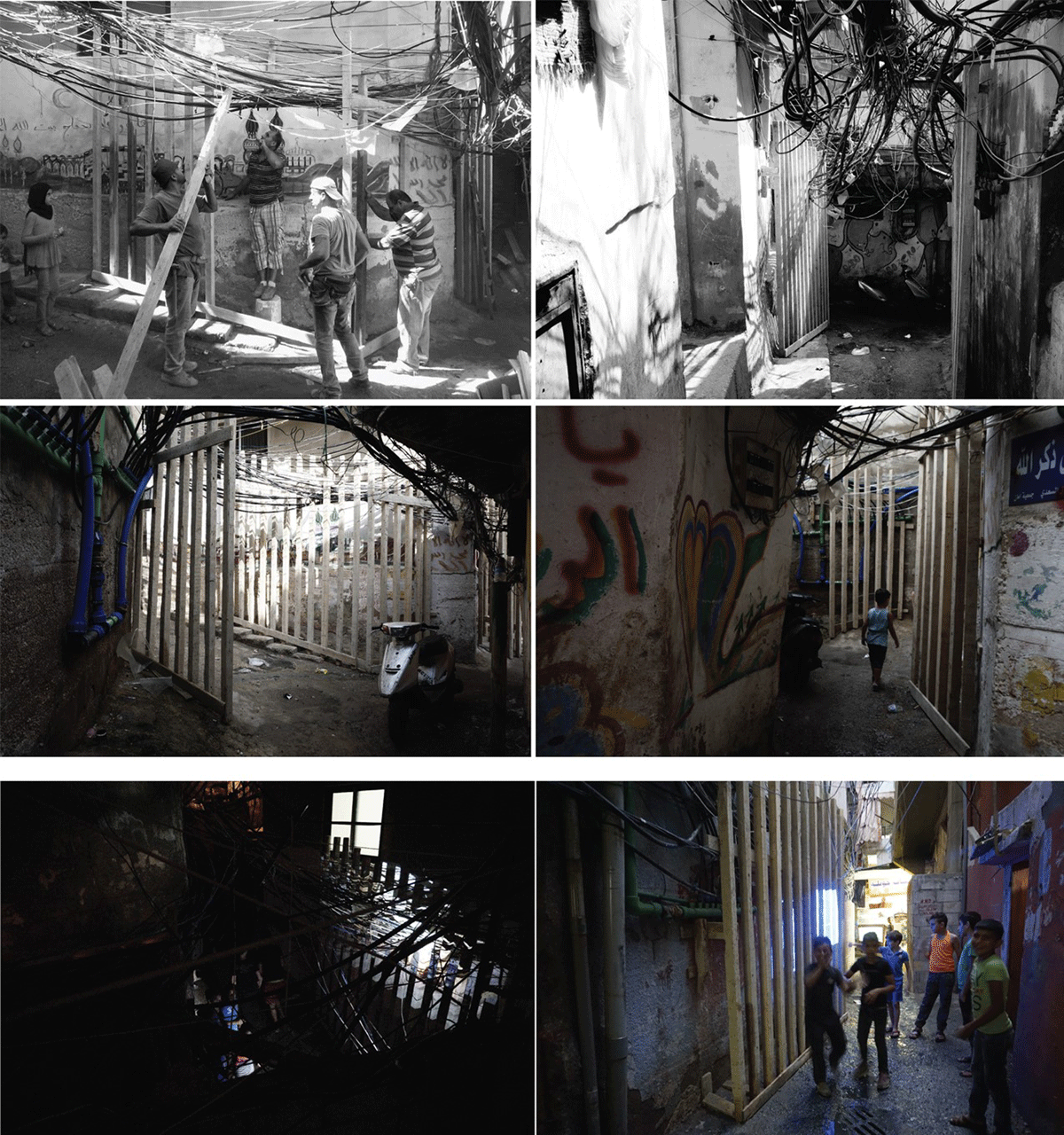

Figure 20

Further photos of installations in the process of being erected for the ‘Space of Refuge’ exhibition in Burj el Barajneh [Courtesy of the author].

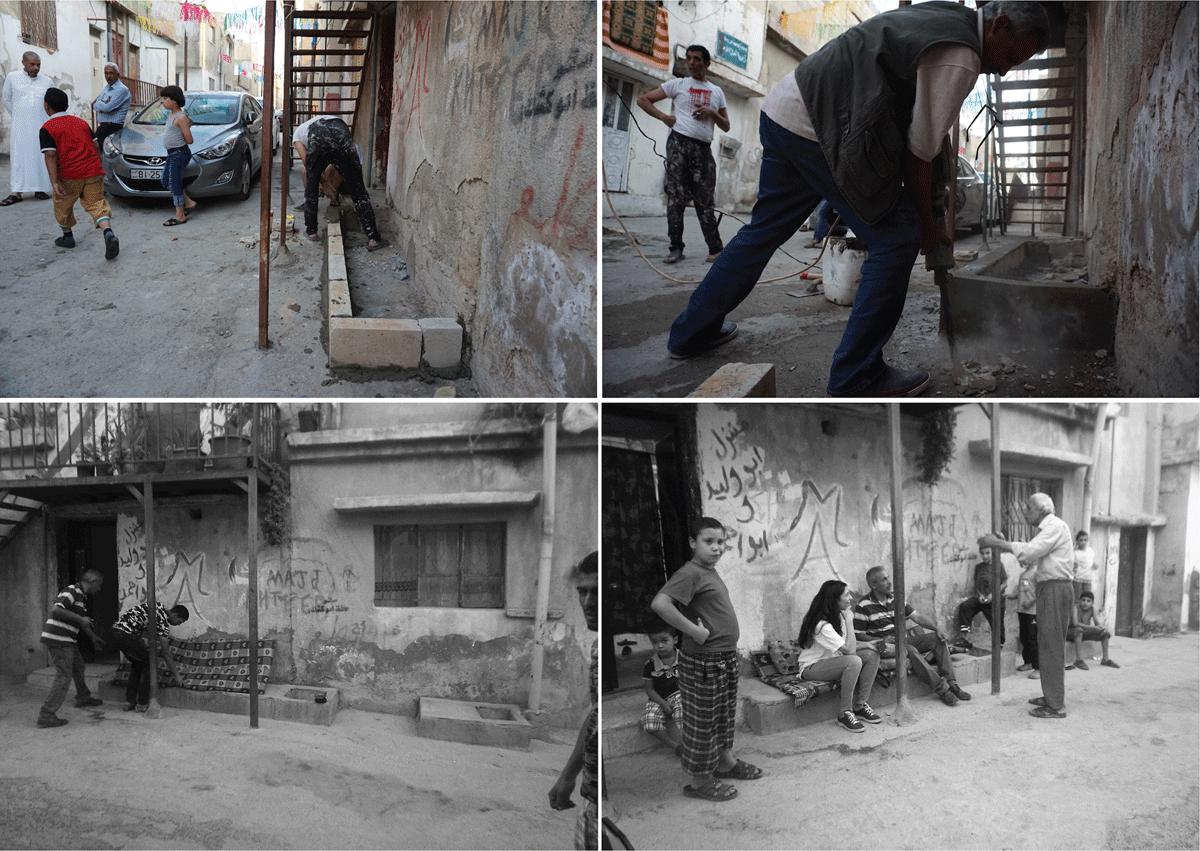

Figure 21

Images of Om Waleed’s Attabat in Baqa’a camp as built in 2015 [Courtesy of the author].

Figure 22

Images of Abu Al’Abed’s Attabat in Baqa’a camp, also erected in 2015 [Courtesy of the author].

Figure 23

Palestinian displacement did not only involve a violent spatial removal, but also a forced reformulation of the customary social traditions and behaviours of village life in a new setting [Courtesy of UNRWA-ICIP Archives].

Figure 24

These recent images show the Attabat for Om Waleed and the lower images the Attabat for Abu Al ’Abed now enriched with greenery [Courtesy of Abu Ahmad and Mohammad Nabulsi].

Figure 25

The proliferation of other Attabat around the Baqa’a camp can be seen in this 2017 photograph, following the lead set by this research project [Courtesy of Mohammad Nabulsi].

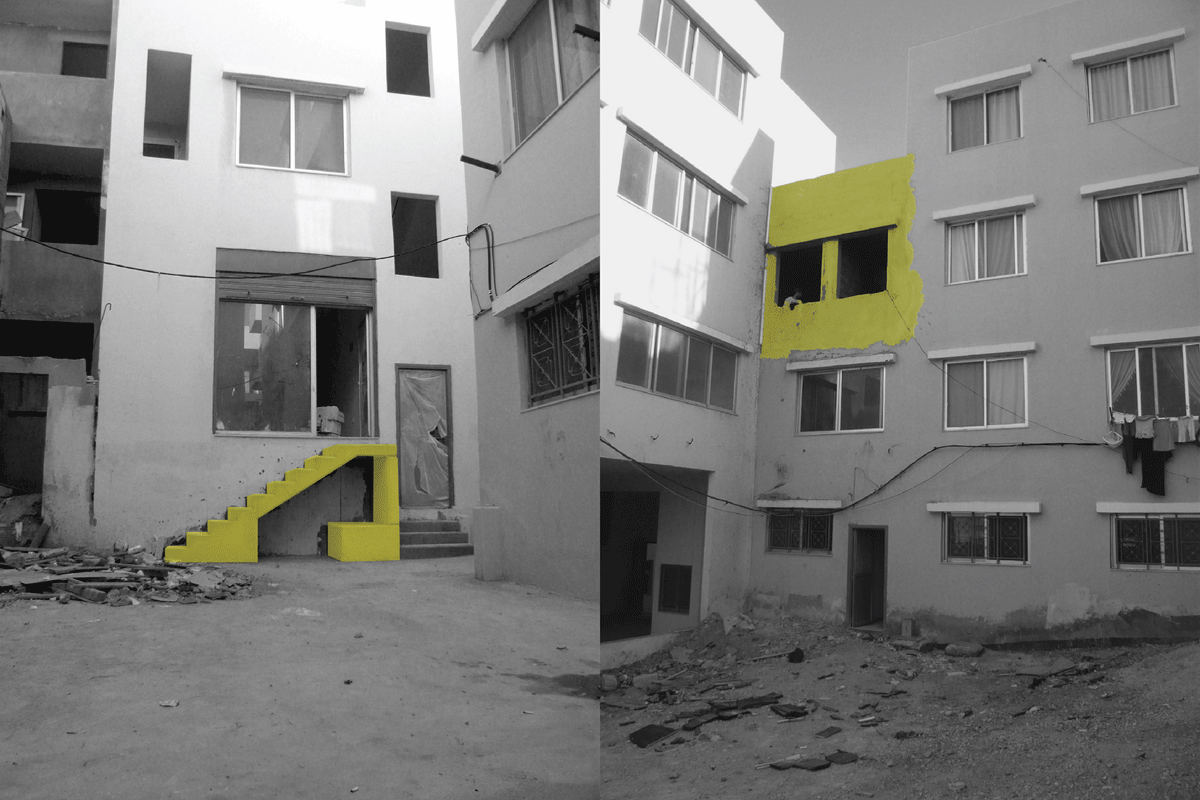

Figure 26

Photographs of ‘spatial violations’ in Nahr el Bared camp in 2012 after its reconstruction, with the yellow highlighting showing how refugees instantly constructed space beyond the parameters laid down by UNRWA and the host government [Courtesy of UNRWA-ICIP Archives].