Atmospheric factors, including light, temperature, humidity, rain and CO2, are often unpredictable, adversely affecting commercial ornamental and vegetable crop production (Gómez et al., 2019). Growers can enhance year-round plant productivity in controlled environments by optimising these conditions with the use of resources such as nutrients and water. Among these conditions, light is the foremost energy source for biological processes, as it plays a crucial role in photosynthesis, plant growth and development. It is essential in triggering various signals for plant morphogenesis and physiological processes (Chen et al., 2004).

Rose is a perennial flowering plant from the Rosaceae family and is characterised by its woody stem. Cut roses with red colour are the most preferred flowers worldwide, and their demand is constantly rising (Kim, 2018). Roses are in high demand not only as ornamental flowering plants but also for their medicinal value (Choi et al., 2015). For the quality and high production of roses, environmental factors such as temperature, light intensity and humidity should be considered. The ideal temperature for growing roses is between 20°C and 30°C during the daytime and 18°C and 20°C at night-time (Ushio et al., 2008). However, in temperate zones, during the summer the highest temperature reaches 35°C and it drops below –5°C in winter (Kim et al., 2022). In addition, natural light intensity varies across seasons, with higher intensity in summer and lower in winter, which may not be sufficient for proper plant growth and development. Therefore, cultivating roses of uniform quality and yielding year-round can be challenging, especially in temperate zones where temperature and light intensity vary significantly during the four seasons (Seo and Kim, 2013). To meet market demand, it is crucial to maintain a stable quality and yield of roses throughout the year by maintaining optimal environmental conditions. This requires careful monitoring and management of various environmental factors related to rose cultivation, which can only be feasible under controlled environmental conditions using artificial light.

Complementary or single-light systems are adopted to enhance plant productivity and quality when natural light is insufficient, as low light intensity adversely affects plant development and quality (Aguirre-Becerra et al., 2020). For instance, when roses were grown in winter, there would be lower yield and decline in quality of roses, including poor pigmentation, reduced stem diameter, small leaves, aborted flower buds and fewer petals because of low photoperiod and light intensity (Moe et al., 2006; Fanourakis et al., 2019). Since light is one of the important factors for photosynthesis, supplementary lights are used to maintain plant productivity during insufficient sunlight (Hamedalla et al., 2022). Supplementary lights with a ratio of 90% red light to 10% blue light at an intensity of 150 μmol · m−2 · s−1 improved not only the growth and photosynthesis of roses but also their yield and quality (Davarzani et al., 2023).

Various artificial light sources, including light-emitting diodes (LEDs), high-pressure sodium (HPS), metal-halide (MH) and fluorescent lamps (FLs), have been adopted to complement the light demand for growing plants (Terfa et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2016; Kyeong et al., 2018; Cho et al., 2020). Terfa et al. (2012) demonstrated that roses (Rosa hybrida 'Toril') grown under LED light exhibited higher anthocyanin and chlorophyll content than those grown under HPS light but with shorter pedicles and stems. Similarly, roses grown under HPS light showed greater height along with leaf area than those grown under LED light (Terfa et al., 2013). Therefore, the effect of different supplementary lights on plant growth should be evaluated. In addition, the selection of supplementary light depends on different light properties, including the spectrum, intensity, heat emission and purpose of its use in the experiment. MH produces a considerable amount of radiation over 400–800 nm wavelength range, but HPS emits little blue radiation, which differently influence photosynthetic capacity by the blue absorbing photoreceptor (Tibbitts et al., 1983). The optimum light intensity and effective wavelength for photosynthesis vary across supplementary lights, depending on environmental conditions and crop variety. For instance, in pak choi, photosynthesis was significantly enhanced under LED supplementary lighting with red (650–670 nm) and blue (455–475 nm) wavelengths at a light intensity of 130 μmol · m−2 · s−1, a temperature of 25°C ± 1°C and a relative humidity of 65 ± 5% (Urrestarazu et al., 2016). By contrast, lettuce showed optimal photosynthesis under LED light with a white (380–780 nm) wavelength, a light intensity of 85– 117 μmol · m−2 · s−1, a temperature range of 18°C–28°C and relative humidity of 80%–85% (Bian et al., 2018).

Although supplementary lighting has transitioned from MH and HPS to LED due to energy efficiency in greenhouses, MH and HPS provide benefits when both lighting and heating are needed. As LEDs emit little heat, they reduce energy demand for lighting but increase the demand for heating. Using the same source for both lighting and heating helps reduce the extra heating load (Katzin et al., 2021). In our experiment, we have chosen the MH and HPS lights because of their ability to provide a broad light spectrum, including green and orange wavelengths as well as a few red and blue wavelengths along with heat-emitting properties, which help maintain the temperature during winter. They also offer several advantages: low cost, relatively long lifespan (MH: 10000–15000 h and HPS: 12000–24000 h) and less energy requirements for additional heating, indicating that they can be used as supplementary lights for plants in terms of heating and lighting during winter (Rea et al., 2009; Darko et al., 2014; Paradiso and Proietti, 2022). However, high operating heat prevents placement of the light near the canopy, which is a drawback of these lights (Darko et al., 2014).

Although there have been some studies on the effect of different supplementary lights on rose growth, there is limited information regarding the impact of combined supplementary lights on rose cultivation on a field scale and assessing the physiological response of roses using non-destructive plant-induced electrical signal (PIES) approach. In this study, we employed two types of light lamps (MH and HPS) and made individual (MH and HPS) and combined (MH + HPS) supplementary light treatments for roses grown under the greenhouse. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the effect of different supplementary light sources, particularly MH, HPS and MH + HPS, as heating lamps on rose growth parameters, assess physiological response with PIES and to determine the feasibility of using light sources as compensation for rose cultivation during winter time.

Roses (R. hybrida L.) cultivar Hazel were cultivated in a greenhouse located in Jincheon-gun, Chungcheongbuk-do, Republic of Korea. To evaluate the effect of different types of supplementary lights on cultivated roses, the experiment was performed in three areas (each area of size 5 m × 10 m), with MH installed in area 1, MH + HPS in area 2 and HPS in area 3. The supplementary light duration was 16 h, from 5 p.m. to 9 a.m. Daytime and night-time temperatures were set at 26°C and 18°C, respectively. Environmental conditions such as photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) were monitored using PYR (Meter group, Pullman, WA, USA), and CO2, relative humidity and atmospheric temperature were monitored using SH-VT260 (SOHA Tech, Seoul, Korea) installed in different locations under different supplementary light sources. Daily light integral (DLI) without supplementary lighting was 1.8 mol · m−2 · day−1. The DLI for MH, MH + HPS and HPS treatments were 2.31, 2.84, and 2.62 mol · m−2 · day−1, respectively. Light spectrum of MH and HPS was measured using BLACK-Comet UV-VIS spectrometer (StellarNet Inc., Tampa, FL, USA). Photon flux density (PFD) was measured between 400 nm and 780 nm and percentages of blue, green, red and far-red lights were calculated based on the light spectrum measured in the ranges of 400–500, 500– 600, 600–700 and 700–780 nm, respectively, relative to the total PFD. The measured spectrum by wavelength is presented in Supplementary Figure 1.

The nutrient solution was supplied by diluting two concentrated nutrient solutions (A and B) in separate tanks. Solution A contained 12.5 g · L−1 KNO3, 54 g · L−1 5[Ca(NO3)2·2H2O]NH4NO3, 1.8 g · L−1 Fe-EDTA and 2 g · L−1 NH4NO3 and solution B contained 20 g · L−1 KNO3, 17.5 g · L−1 KH2PO4, 30 g · L−1 MgSO4·7H2O, 8 g · L−1 Mg(NO3)2, 280 mg · L−1 H3BO3, 200 mg · L−1 MnSO4·H2O, 120 mg · L−1 ZnSO4·7H2O, 24 mg · L−1 CuSO4·5H2O and 24 mg · L−1 NaMoO2·2H2O. To analyse the nutrient content of the rhizosphere medium, the solution was collected with a syringe and filtered through a 0.45 μm syringe filter. Ammonium nitrogen (NH4+–N) and NO3––N content of the nutrient solution were analysed by indophenol-blue method and VCl3 reduction method, respectively (Dorich and Nelson, 1983; Doane and Horwáth, 2003). The nutrient concentrations such as Ca, Mg, K, P and S were analysed using inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) (Avio 500, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Nutrient concentrations of media are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

To evaluate the growth of roses according to different light sources during night-time in winter, growth parameters such as height, stem diameter, number of leaves, leaf length, leaf width, flower diameter, flower length and number of petals were investigated. The plant photosynthetic capacity, chlorophyll content and chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm) of roses cultivated under different supplementary lights were measured using a chlorophyll meter (SPAD-502Plus, KONICA MINOLTA, Tokyo, Japan) and FluorPen (FluorPen FP 110/D, Phyton Systems Instruments, Drásov, Czech Republic), respectively. Leaves were covered with a dark clip for 20 min and dark-adapted leaves were measured for Fv/Fm.

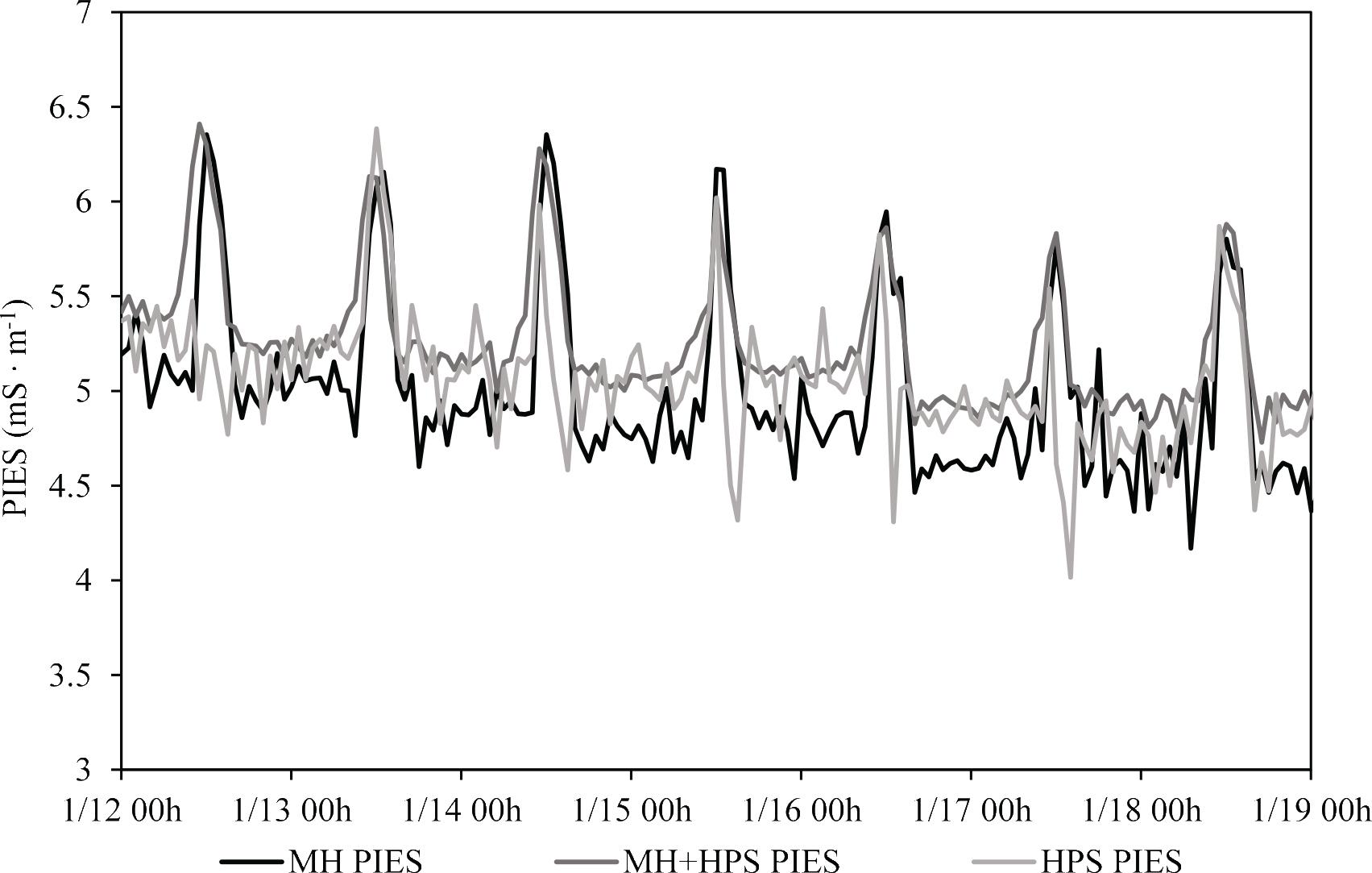

PIES was also monitored to evaluate the physiological activity of roses cultivated under different light sources. The PIES sensor, comprising three stainless steel needles, was inserted into the rose stem to measure the electrical resistance generated when the roses absorb nutrients and water. The electrical resistance was monitored using Junsmeter II (Prumbio, Suwon, Korea) (Kim et al., 2023). The electrical resistance was converted to electrical conductivity using equation reported by Kim et al. (2023). The PIES and other parameters were compared with averages calculated for specific periods during the day and night.

Statistical analysis was performed by the SPSS software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and Xlstat (Addinsoft, Paris, France). Eight rose samples from each area were measured and the collected data were averaged from the eight replicates and reported as mean with standard deviation. Means were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Duncan’s multiple range test at a significance level of p < 0.05. The principal component analysis (PCA) was also performed to understand the correlation among light treatments, growth parameters and nutrient contents of the medium.

The atmospheric temperature was similar in all the three treatment areas except for night-time temperature over a daily period. The highest night-time temperature was observed in the MH + HPS area, followed by the MH and HPS areas, and daytime temperature was not much different among areas because of natural light (Figure 1A). An inverse relationship was found between temperature and relative humidity in the treatment areas, with MH + HPS treatment resulting in a lower relative humidity level than other treatments because of slightly higher temperature during night-time (Figure 1A). During the night, lower relative humidity and higher temperature observed in the MH + HPS area suggested that roses grown under this condition had a higher transpiration rate than other supplementary lights.

Monitoring of the environmental conditions for rose cultivation: (A) relative humidity and atmospheric temperature and (B) PPFD and atmospheric CO2 under different supplementary lights. HPS, high-pressure sodium lamps; MH, metal-halide lamps; MH + HPS, metal-halide+high-pressure sodium lamps; PPFD, photosynthetic photon flux density.

The PPFD pattern exhibited a slight variation during the night-time, while it remained consistent across all the three treatments in the daytime, with minor variations in peak intensity (Figure 1B). The highest PPFD was observed in the MH + HPS area at night-time, indicating that combined light (MH + HPS) might provide a broad spectrum and higher light output, resulting in an elevated PPFD. In the case of CO2, the graph pattern for day and night was observed to be the same for all the treatment areas, with a smaller variance noted during the night-time, which could be due to the small amount of photosynthetic activation by HPS at night using energy stored during the day (Figure 1B). The area with the highest concentration of CO2 was found in the order of MH > MH + HPS = HPS treatment although the difference was not significant. The results suggest that MH light intensity and spectra may not be effective as supplementary lights compared with other lights. Tibbitts et al. (1983) reported that hypocotyl elongation of lettuce, spinach and mustard was better under HPS than MH, which might be attributed to 5%–10% higher photosynthetic efficiency of plants under HPS than MH.

The results demonstrated that the height, length of leaves, leaf width, flower length and petal number of rose plants were observed to be the greatest in the MH + HPS area, followed by the HPS and MH areas, but their difference was insignificant among the three treatment areas (Table 1). The spectral properties of HPS and MH showed different light spectrum percentages (Table 2). The HPS light exhibited highest percentage of red (R, 36%) spectra, followed by green (G, 34%), blue (B, 16%) and far-red (FR, 14%). For the MH light, the order of spectrum percentage was G (29%), R (29%), FR (23%) and B (19%), respectively. The metal-halide G and R light percentages were lower than the HPS light, but B and FR percentages were higher under MH light (Table 2). The roses cultivated in the MH+HPS area had significantly higher stem diameters (7.3 ± 1.9 mm) than the MH and HPS areas, which could be attributed to high R light, high light intensity and high atmospheric temperature in the MH + HPS area (Figure 1A,B). Hosseini et al. (2019) revealed that R light was positively correlated with plant stem diameter. According to Yasar et al. (2022), the plant stem diameter was significantly influenced by variations in light intensity and temperature. They found that tomato plants exposed to high supplementary light and high temperature had the highest stem diameter relative to low supplementary light and low temperature.

Effect of different supplementary lights on growth parameters, chlorophyll content and Fv/Fm content of the rose plants.

| Supplementary lights | Height (mm) | Stem diameter (mm) | Number of leaves | Leaf length (mm) | Leaf width (mm) | Flower diameter (mm) | Flower length (mm) | Number of petals | Chlorophyll content (SPAD) | Fv/Fm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MH | 72.0 ± 6.7 a | 5.4 ± 0.5 b | 8.3 ± 0.8 b | 13.4 ± 0.8 a | 13.2 ± 0.9 a | 4.7 ± 0.3 b | 5.1 ± 0.2 a | 46.5 ± 4.4 a | 37.9 ± 2.7 a | 0.8 ± 0.0 a |

| MH ± HPS | 82.5 ± 11.8 a | 7.3 ± 1.9 a | 10.5 ± 0.7 a | 13.6 ± 0.9 a | 13.5 ± 0.9 a | 5.1 ± 0.4 a | 5.1 ± 0.4 a | 46.8 ± 3.5 a | 40.8 ± 3.7 a | 0.8 ± 0.1 a |

| HPS | 73.7 ± 11.2 a | 5.8 ± 1.1 b | 9.6 ± 1.9 a | 13.4 ± 0.9 a | 13.3 ± 1.0 a | 5.0 ± 0.4ab | 5.1 ± 0.5 a | 47 ± 4.6 a | 38.6 ± 2.6 a | 0.8 ± 0.0 a |

Statistically significant values are denoted by different letters at p < 0.05.

HPS, high-pressure sodium lamps; MH, metal-halide lamps; MH + HPS, metal-halide + high-pressure sodium lamps; Fv/Fm, chlorophyll fluorescence.

Percentage of light spectrum of HPS and MH lights for roses.

| Light properties | HPS (%) | MH (%) |

|---|---|---|

| PFD | 100 | 100 |

| Blue (400–500 nm) | 16 | 19 |

| Green (500–600 nm) | 34 | 29 |

| Red (600–700 nm) | 36 | 29 |

| FR (700–780 nm) | 14 | 23 |

FR, far-red; HPS, high-pressure sodium; MH, metal-halide; PFD, photon flux density.

A higher number of leaves were also found in the MH + HPS and HPS areas, followed by MH. The roses grown in the MH + HPS and HPS areas had significantly greater number of leaves than those grown in the MH area because of slightly higher light intensity (PPFD) of about 20 μmol · m 2 · s and higher temperature in the MH + HPS and HPS areas than in the MH area during night-time. Mccall (1992) showed that tomato plants exposed to higher light intensity exhibited a greater number of leaves. Díaz-Pérez (2013) also reported that low light intensity decreased the number of leaves of pepper plants. The study on the effect of daytime LED supplementary lighting (PPFD: 180 μmol · m 2 · s−1) with and without 4 h night-time supplementary lighting (PPFD: 10 μmol · m 2 · s−1) on morphogenesis of Petunia hybrida revealed that providing daytime supplementary blue–red (BR) light combined with 4 hr night-time supplementary light increased the number of leaves of P. hybrida (Park and Jeong, 2023).

Flower diameter of roses cultivated in the MH + HPS area showed a substantially higher diameter relative to HPS and MH. Overall growth parameters positively induced under MH + HPS supplementary light can be attributed to synergistic effects of unique spectrum under combined light (MH + HPS: G, R, B and FR) inducing more rose growth, as opposed to single light spectrum. The roses cultivated under HPS light induced slightly higher growth parameters than those treated under MH light, which might be due to higher R light (36%) and B light (16%) under HPS light, eventually inducing more photosynthesis (Matysiak, 2021). According to Matysiak (2021), a high proportion of R light combined with 13%–16% B and 10%–15% green-yellow light promoted photosynthesis in rose (R. hybrida 'Aga') plants. In addition, potatoes grown under HPS supplementary light had noticeably longer stems than those grown under MH light (Yorio et al., 1995). One of the possible reasons for shorter height under MH supplementary light could be high blue light (B-light) percentage relative to other lights (Table 2) because high B-light has been observed to impede cell expansion and growth in various plant species (Dougher and Bugbee, 2004). Dougher and Bugbee (2004) reported that soybeans grown without exposure to B-light exhibited greater stem length than those exposed to 26% B-light. These results concluded that diminished growth parameters could be related to the higher proportion of B-light and hence negatively affected plant elongation and morphology.

In addition to B-light, the R to FR ratio (R:FR) significantly modulates various aspects of plant growth, such as leaves expansion, stem elongation, reproduction and branching (Zheng et al., 2019). The modulation of various factors, such as ethylene, auxin, gibberellins, abscisic acid and cytokinin, through light plays a crucial role in plant development (Xu et al., 2021). Wang et al. (2024) showed that supplementary LED lighting during winter night enhanced the levels of plant hormones such as auxin, gibberellin, jasmonic acid and salicylic acid in pitaya orchards, which are mainly responsible for flowering and plant growth. In our study, roses grown under MH + HPS supplementary light showed better growth than those grown under other supplementary lights, which might be attributed to the changes in the rose hormones under MH + HPS light and eventually changes in their growth because the MH and HPS supplementary lights can alter plant hormones as proved by Ubukawa et al. (2004).

The SPAD value is associated with the chlorophyll content in the plant, which evaluates leaves colour (Yoo et al., 2021). The Fv/Fm ratio, an indicator of chlorophyll photosynthetic efficiency, remained unchanged across all the treatments, indicating a uniform photosynthetic performance (Table 1). Although chlorophyll content and Fv/Fm were not significantly different, the highest chlorophyll content was reflected by the roses grown in the MH + HPS area than those grown in the HPS and MH areas (Table 1). The combined light (MH + HPS) had greater light intensity, eventually inducing higher chlorophyll synthesis (Okamoto et al., 2020). According to Okamoto et al. (2020), chlorophyll synthesis was mainly related to light intensity, and the content of chlorophyll rose logarithmically in potato plants with increasing light intensity.

The highest peak intensity was observed during the daytime because transpiration is more active under natural light and high temperature. Although it was not much different during the day, the PIES signals for roses cultivated in all the three treatment areas during night were higher in the MH + HPS area, followed by the HPS and MH areas (Figure 2). These results suggest that the physiological activity of the cultivated roses in the MH + HPS area was higher during night-time because PIES reflects the uptake of water and nutrients by the plants (Park et al., 2018). In this study, environmental factors during the day did not affect the PIES signal because all factors were almost the same in all the three treatment areas. During the night-time, PPFD and temperature were higher and relative humidity was lower in the MH + HPS area, which could be responsible for higher nutrient uptake by the roses cultivated in the MH + HPS area, which was eventually correlated with PIES signals because these factors enhanced the transpiration process. Previous research reported that plants can absorb more nutrients by adopting the light intensity and spectra they are exposed to, which affects plant photomorphogenesis (Pinho et al., 2017; Clavijo-Herrera et al., 2018; Pennisi et al., 2019). For instance, Bueno and Vendrame (2024) found that Phaseolus vulgaris L. exhibited higher nutrient uptake when exposed to white and pink spectra than other light spectra.

Monitoring of PIES of roses cultivated under different supplementary lights. HPS: high-pressure sodium lamps; MH, metal-halide lamps; MH + HPS, metal-halide + high-pressure sodium lamps.

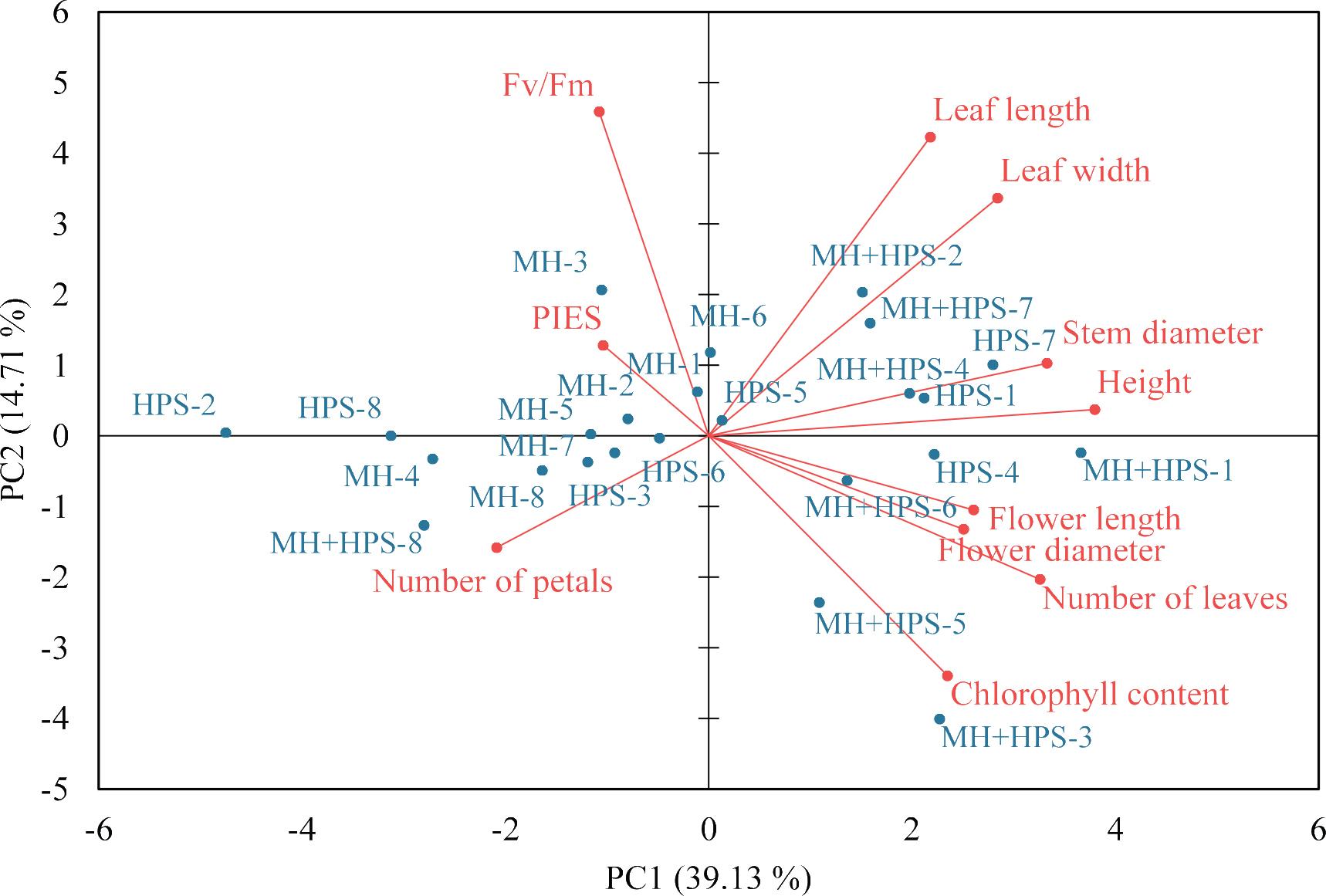

To understand the relationship among growth parameters, chlorophyll content, Fv/Fm and PIES of roses grown under different supplementary lights, PCA was conducted. PCA is a widely used technique in data analysis to identify correlations and interdependencies among samples and reduce the dimensionality of high-dimensional datasets (Šamec et al., 2016). The first three principal components (PC) in the analysed dataset, PC1, PC2 and PC3, represented 39.13%, 14.71% and 10.37% of the total variation, respectively (Figure 3; Table 3).

Biplot of PC (PC1 and PC2) for the growth parameters with rose Fv/Fm and chlorophyll content under different supplementary lights. HPS, high-pressure sodium lamps; MH, metal-halide lamps; MH+HPS, metal-halide + high-pressure sodium lamps.

Factor loadings and variance explained by the first three principal components (PC1, PC2 and PC3).

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PIES | –0.250 | 0.190 | –0.322 |

| Height | 0.915 | 0.055 | –0.221 |

| Stem diameter | 0.802 | 0.152 | –0.142 |

| Number of leaves | 0.786 | –0.300 | –0.254 |

| Leaves length | 0.525 | 0.625 | 0.323 |

| Leaves width | 0.685 | 0.498 | 0.270 |

| Flower diameter | 0.604 | –0.195 | 0.368 |

| Flower length | 0.628 | –0.155 | 0.354 |

| Number of petals | –0.502 | –0.233 | 0.617 |

| Chlorophyll content | 0.566 | –0.502 | –0.196 |

| Fv/Fm | –0.259 | 0.677 | –0.215 |

| Eigenvalue | 4.305 | 1.618 | 1.140 |

| Variability (%) | 39.135 | 14.706 | 10.366 |

| Cumulative (%) | 39.135 | 53.840 | 64.206 |

Values highlighted in bold refer to loading values >0.5.

Fv/Fm, chlorophyll fluorescence; PIES, plant-induced electrical signal.

The PCA analysis showed that growth parameters such as rose height, stem diameter, number of leaves, leaf length, leaf width, flower diameter and flower length were positively loaded, while number of petals was negatively loaded on PC1 (Figure 3; Table 3). Leaf length and Fv/Fm were primarily influenced by PC2 (Figure 3). PCA biplot showed that the PC1 strongly contributed to the separation of MH + HPS light from other lights and MH + HPS light was substantially related to the growth parameters of roses (Figure 3). Fv/Fm was correlated with PIES; however, the growth of roses was not differentiated in the MH and HPS areas because environmental conditions, including atmospheric temperature, relative humidity, PPFD and CO2 concentration, were almost consistent across these areas.

Supplementary light sources in a greenhouse environment influence the growth characteristics of rose plants. The growth parameters were slightly superior under MH + HPS light, suggesting that the combined MH + HPS lights (R, G, B, FR and R:FR ratio) enhanced the growth of roses. Physiological activity of roses cultivated under MH + HPS supplementary lights during night was confirmed to be higher, followed by HPS and MH lights, as indicated by PIES measurement. Although overall rose growth and development were not differentiated between MH and HPS supplementary lights, the combined treatments of MH + HPS lights were superior to the MH supplementary light. Considering the durability and cost of HPS and MH lights, HPS lights have greater durability and low maintenance, while MH lights have lower installation costs. Therefore, combining both types compensates for the disadvantages of each as well as enhances rose growth in winter.