Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a type of aggressive lymphoma characterized by significant heterogeneity in both clinicopathological and genetic features (Tang et al. 2021). Morphologically, DLBCL is defined by the diffuse proliferation of neoplastic large B lymphocytes (Liu et al. 2023). DLBCL is the most common subtype of lymphoma, accounting for 30%–40% of adult non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-positive DLBCL (EBV+ DLBCL) is a newly defined DLBCL subgroup (Narita and Takeuchi 2023; Shold et al. 2024). In recent years, various natural drugs and their active components have been shown to exhibit a beneficial effect in modulating the progression of DLBCL (Zhang et al., 2024; Seog et al. 2025). However, to further improve the prognosis of patients, the development of novel and more effective therapeutic drugs remains a crucial need.

Boluohui (Macleaya cordata (Willd.) R. Br.), a medicinal herb from the Papaveraceae family, has been traditionally used for its anticancer properties (Du et al. 2024). According to Chinese herbal literature records, Boluohui is mainly used in the treatment of skin cancer and body surface tumors, cervical cancer, and thyroid cancer, showing significant therapeutic effects (Du et al. 2024). Sanguinarine (SAG) has been shown to inhibit the growth and progression of various cancers, primarily in studies using immortalized cell lines, such as melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and colorectal cancer models (Prabhu et al. 2021; Pallichankandy et al. 2023; Huang et al. 2024). Recent studies have demonstrated that SAG exerts anticancer effects on cancer cells by inhibiting the motility of melanoma by targeting the FAK/PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis (Huang et al. 2024). Additionally, SAG mediates apoptosis in NSCLC cells by generating reactive oxygen species and inhibiting the JAK/STAT signaling pathway (Prabhu et al. 2021). In colorectal cancer, SAG inhibits cell migration and metastasis through the reversal of EMT by targeting Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Pallichankandy et al. 2023). Although SAG has an important inhibitory effect on various tumors, its role in the progression of DLBCL remains unknown.

The activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway plays a key role in the transcription of proteins involved in cell proliferation, protein synthesis, and tumor growth (Xing et al. 2023, 2024). This pathway, which is crucial in the development of many cancers, is activated in DLBCL (Xing et al. 2023). Abnormal regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathways leads to β-catenin accumulation, followed by its nuclear translocations and activation of downstream target genes (Xing et al. 2023). In EBV-positive DLBCL, progression is offset by the modulation of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)/β–catenin axis (Xing et al. 2024). The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is integral to EBV-positive DLBCL, as it promotes tumor proliferation, survival, and immune evasion (Xing et al. 2023). Aberrant activation of this pathway drives the expression of oncogenic targets like c-Myc and Cyclin D1, which contribute to malignant progression (Xing et al. 2023). In EBV-positive DLBCL, viral proteins such as LMP1 may further activate this pathway, highlighting its potential as a potential therapeutic target for this aggressive form of lymphoma.

Despite advancements in treatments such as R-CHOP, a significant proportion of DLBCL patients, particularly those with EBV-positive DLBCL, experience resistance or relapse, highlighting the limitations of current therapies (Xing et al. 2024). The lack of targeted agents addressing specific molecular pathways, such as Wnt/β-catenin, further emphasizes the need for novel therapeutic approaches. This gap in treatment underscores the potential significance of SAG as a promising agent in addressing the challenges posed by this aggressive lymphoma subtype.

Herein, we aimed to elucidate the effects of SAG on DLBCL progression. Our data confirmed that SAG inhibits cell growth in EBV-positive DLBCL. Based on these findings, we propose that SAG could serve as a potential drug to combat this disease.

The EBV-positive DLBCL cell lines FARAGE and GM12878 along with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were used in this study. Cell line authentication was performed using short tandem repeat profiling to ensure the identity and authenticity of the EBV-positive DLBCL cell lines. These cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Beyotime, Shanghai, China; C0222) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Beyotime, C04001). The cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

SAG was purchased from Beyotime and dissolved in DMSO to prepare stock solutions. DMSO-treated cells served as the vehicle control to account for any solvent-related effects. Antibodies used in this study were obtained from Abcam (Combridge, UK), including anti-Bax (ab32503, 1:1000), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (ab32042, 1:1000), anti-Axin (ab32197, 1:1000), anti-β-catenin (ab16051, 1:1000), and anti-c-Myc (ab32072, 1:1000). Antibody specificity was validated by the manufacturers through Western blot and immunohistochemistry in the respective target-positive controls.

Cell viability was assessed using the cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) (Beyotime, C0038). Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well and treated for 48 h. The OD450 value was measured using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

Cell proliferation was evaluated using BrdU (Beyotime, C1161S). After treatment, cells were incubated with BrdU for 2 h. The percentage of BrdU-positive cells was visualized using a Zeiss (Oberkochen, Germany) LSM710 microscope and quantified.

Cells were fixed in 70% ethanol overnight at 4°C. The cells were then stained with propidium iodide (PI; Beyotime, C1052) and analyzed using a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA; FACSCalibur).

Apoptosis was detected using the Kit (Beyotime, C1062M). Cells treated with SAG (5 μM, 10 μM, and 20 μM) for 48 h were harvested and stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined (BD Biosciences, USA; FACSCalibur) using flow cytometer.

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Burlington, USA, IPVH00010). The membranes were blocked with 5% fat-free milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) and incubated with primary antibodies and membranes, which were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Beyotime) and visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific; iBright FL1500).

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

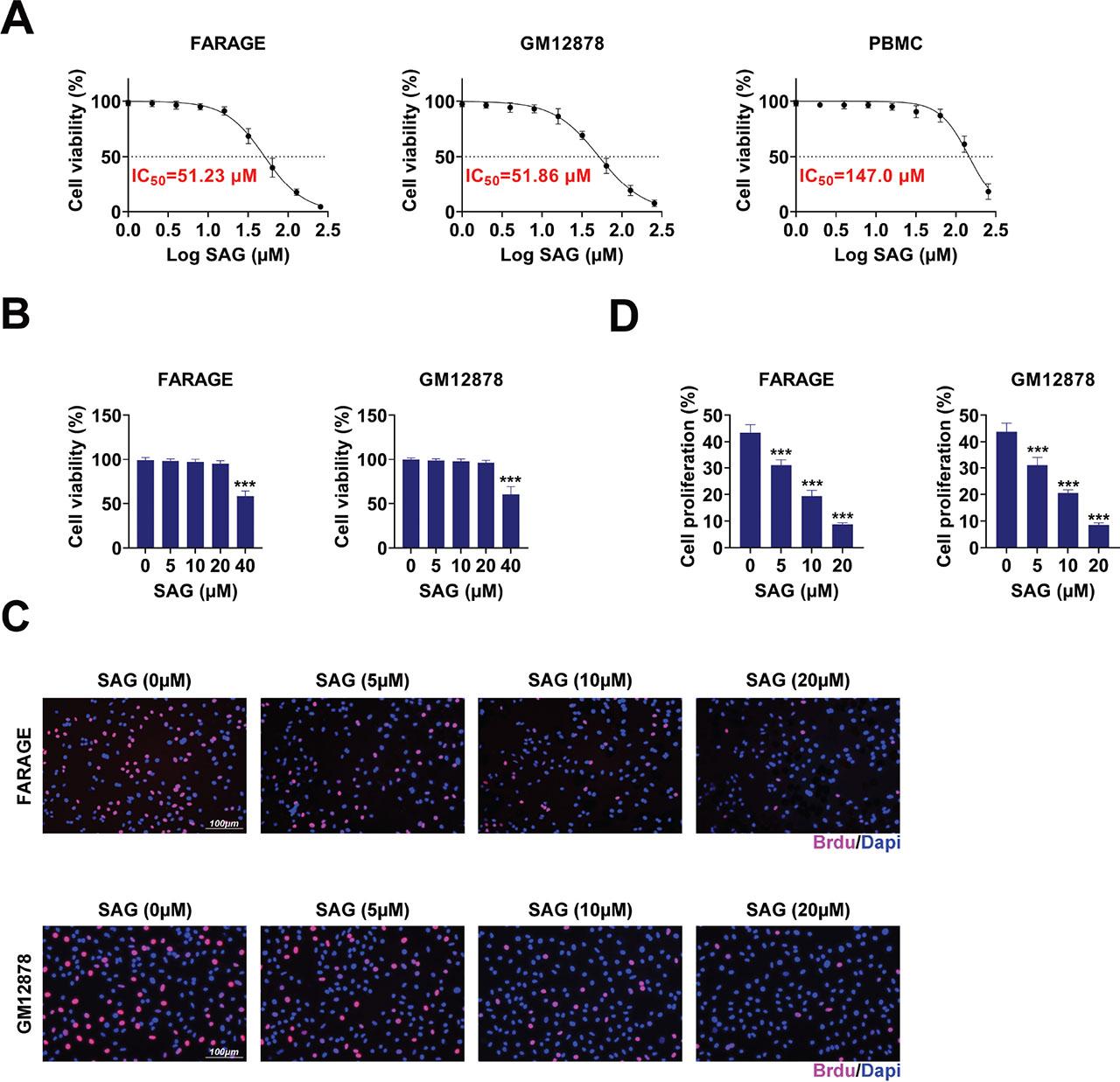

We first investigated the effect of SAG on the cell viability of EBV-positive DLBCL cell lines, including FARAGE and GM12878S. FARAGE and GM12878S cells were treated with SAG (0 μM, 5 μM, 10 μM, 20 μM, and 40 μM), and cell viability was assessed after 48 h via CCK-8 assays. The IC50 value of SAG on the FARAGE and GM12878S cells and normal PBMCs are shown in Figure 1a (51.23 μM, 51.86 μM, and 147.0 μM, respectively). We noticed that SAG (40 μM) suppressed the growth of FARAGE and GM12878S cells in a dose–dependent manner (Figure 1b). Although 40 μM SAG exhibited strong inhibitory effects on cell viability, concentrations above 20 μM were excluded from subsequent experiments due to concerns about non-specific cytotoxicity, thereby minimizing potential artifacts associated with excessive compound exposure (Figure 1b). Furthermore, BrdU assays also confirmed that treatment of SAG (5 μM, 10 μM, and 20 μM) inhibited the growth of FARAGE and GM12878S cells, as evidenced by the decreased percentage of BrdU-positive cells in a dose–dependent manner (Figures 1c,d). These results indicate that SAG effectively suppressed the growth of FARAGE and GM12878 cells.

SAG suppressed the growth of FARAGE and GM12878 cells. (a) IC50 of SAG in the indicated cell lines. (b) CCK-8 assays showed the growth of FARAGE and GM12878 cells upon treatment with SAG at concentrations of 5 μM, 10 μM, 20 μM, and 40 μM for 48 h. The OD450 value was measured. (c) BrdU assays showed the growth capacity of FARAGE and GM12878 cells following treatment with SAG at concentrations of 5 μM, 10 μM, and 20 μM for 48 h. The red panel indicates BrdU. (d) Quantification of panel C, the percentage of BrdU positive cells are shown. Scale bar, 100 μm. The percentage of BrdU positive cells was measured. ***p < 0.001. CCK-8, cell counting kit-8; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; SAG, Sanguinarine.

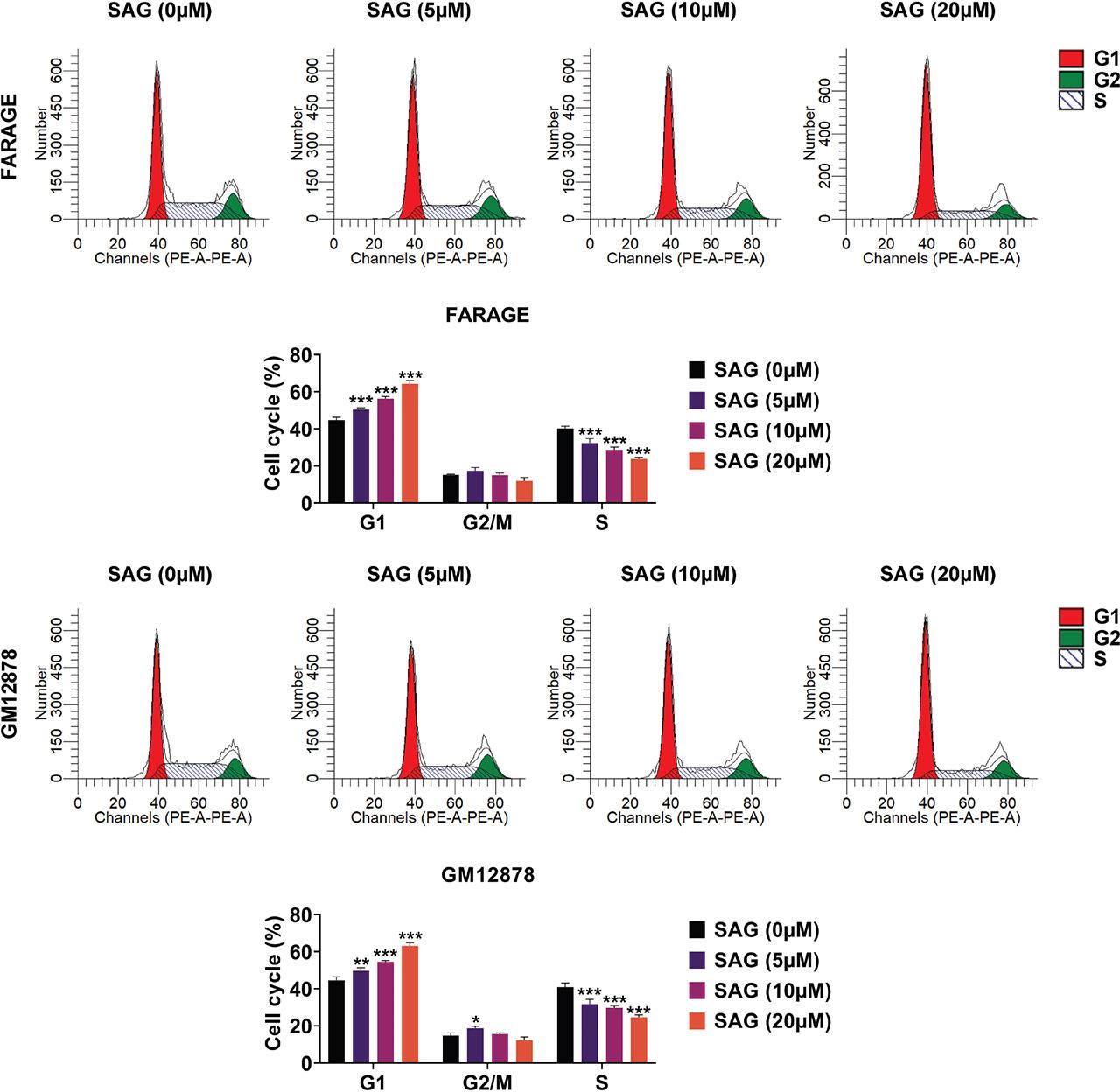

To assess the anti-cell cycle properties of SAG, we evaluated the cell cycle progression in FARAGE and GM12878S cells. Flow cytometry assays revealed that treatment with SAG (5 μM, 10 μM, and 20 μM) induced cell cycle arrest, with increased cells at G1 and decreased cells at the G2 phase in a dose–dependent manner (Figure 2). These findings suggest that SAG effectively stimulates cell cycle arrest in FARAGE and GM12878S cells.

SAG stimulated cell cycle arrest in FARAGE and GM12878 cells. Flow cytometry assays demonstrated the cell cycle difference in FARAGE (up) and GM12878 (down) cells upon treatment with SAG at concentrations of 5 μM, 10 μM, and 20 μM for 48 h. The percentage of cells at G1, G2/M, and S phases was calculated and compared. ***p < 0.001. SAG, Sanguinarine.

We next explored the impact of SAG on apoptosis in FARAGE and GM12878S cells using flow cytometry and immunoblot analysis. Cells were treated with SAG (5 μM, 10 μM, and 20 μM). Flow cytometry analysis indicated an increase in the percentage of apoptotic cells with SAG treatment in a dose–dependent manner (Figure 3a). Immunoblot analysis further confirmed that SAG increased cleaved-caspase3 and Bax levels in FARAGE and GM12878S cells, suggesting the stimulation of cell apoptosis (Figure 3b). These results demonstrate that SAG significantly stimulates apoptosis in FARAGE and GM12878S cells.

SAG stimulated cell apoptosis in FARAGE and GM12878 cells. (a) Flow cytometry assays showed the apoptosis degree of FARAGE (up) and GM12878 (down) cells upon treatment with SAG at concentrations of 5 μM, 10 μM, and 20 μM for 48 h. The percentage of apoptosis cells was calculated and compared. (b) Immunoblot analysis showed the expression of Bax and cleaved caspase-3 in FARAGE (left) and GM12878 (right) cells after treatment with SAG at concentrations of 5 μM, 10 μM, and 20 μM for 48 h. The relative expression of Bax and cleaved caspase-3 is shown. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. SAG, Sanguinarine.

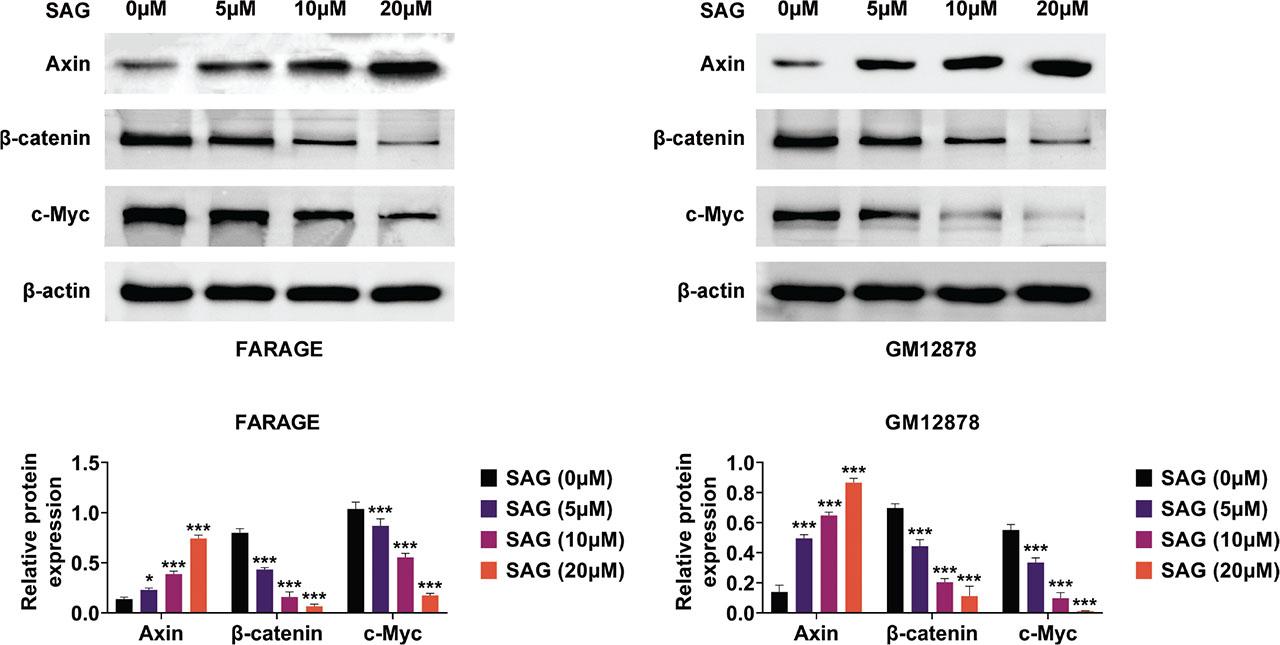

To understand the mechanism behind the anti-proliferation as well as pro-apoptotic effects of SAG, we assessed the Wnt/β–catenin axis in EBV-positive DLBCL cells. Cells treated with SAG (5 μM, 10 μM, and 20 μM) were subjected to immunoblot analysis to measure the expression of key regulators in the Wnt/β–catenin axis, including Axin, beta-catenin, and c-Myc. In response to increasing concentration, SAG significantly enhanced the expression of Axin and decreased the levels of β-catenin and c-Myc, indicating suppression of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in both FARAGE and GM12878S cells (Figure 4). These findings suggest that SAG exerts its anti-proliferation and pro-apoptotic effects via suppression of the Wnt/β–catenin axis.

SAG restrained the Wnt/beta–catenin axis in FARAGE and GM12878 cells. Immunoblot analysis showed the expression of Axin, c-Myc, and beta-catenin in FARAGE (left) and GM12878 (right) cells upon treatment with SAG at concentrations of 5 μM, 10 μM, and 20 μM for 48 h. The relative expression levels of Axin, c-Myc, and beta-catenin are shown. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. SAG, Sanguinarine.

DLBCL is a highly aggressive and heterogeneous subtype of lymphoma (Narita and Takeuchi 2023; Ren et al. 2023; Xing et al. 2024). The pathogenesis of DLBCL contains multiple genetic alterations that disrupt several cellular processes such as cell apoptosis (Lu et al. 2020; Xing et al. 2023). Natural products and their active compounds have attracted considerable attention due to the potential to modulate these critical cellular processes (Liu et al. 2023; Yang et al. 2023). In this study, we investigated the effects of SAG on EBV-positive DLBCL cells. Our findings demonstrate that SAG effectively inhibits the growth of EBV-positive cells by inducing cell cycle arrest and promoting apoptosis. These results suggest that SAG could serve as a promising therapeutic agent for DLBCL.

The presence of EBV in DLBCL represents a distinct clinical entity with a poorer prognosis compared with EBV-negative DLBCL (Hu et al. 2018; Zhan and Teruya-Feldstein 2019). EBV-positive DLBCL is featured by the clonal proliferation of EBV+ B cells, which contributes to the oncogenic process (Zhan and Teruya-Feldstein 2019). The association of EBV with DLBCL introduces unique molecular mechanisms that can be targeted for therapeutic intervention (Ohashi et al. 2017; De Souza et al. 2024). Therefore, it is crucial to develop strategies that specifically target EBV-positive cells to improve the treatment outcomes for patients. This study focused on the EBV-positive DLBCL cell lines FARAGE and GM12878, which served as in vitro models to investigate the effects of SAG. We observed that SAG selectively inhibited the growth of these EBV-positive cells, providing evidence that SAG might be particularly effective in treating EBV-positive DLBCL. This finding underscores the importance of considering EBV status in the development of targeted therapies for DLBCL.

SAG has been recognized for its potent anticancer properties across various malignancies (Alakkal et al. 2022; Qin et al. 2022). It exerts its effects by modulating key signaling pathways that govern cell growth, apoptosis, and metastasis (Alakkal et al. 2022; Qin et al. 2022). In the context of DLBCL, this study revealed that SAG significantly inhibited the proliferation of EBV-positive DLBCL cells. This antiproliferative effect was accompanied by a notable induction of cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase. Moreover, SAG also promoted apoptosis in these cells, further demonstrating its potential as an anticancer agent. SAG could target multiple signaling pathways to exert its anticancer effects (Prabhu et al. 2021; Qi et al. 2023). The ability of SAG to influence both cell cycle progression and apoptotic pathways highlights its therapeutic potential for DLBCL treatment.

While this study highlights the potential of SAG in targeting EBV-positive DLBCL, it is worth noting that current standard therapies, such as R-CHOP, primarily focus on broad-spectrum cytotoxicity rather than specific molecular pathways like Wnt/β-catenin. Compared with these therapies, SAG’s ability to specifically inhibit the Wnt/β–catenin axis may offer a targeted approach with potentially fewer off-target effects. However, direct comparisons in terms of efficacy, toxicity, and therapeutic index are necessary to further investigate SAG’s potential as an adjunct or alternative to existing regimens.

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is vital for maintaining cellular homeostasis and is frequently dysregulated in DLBCL (Xing et al. 2023). Aberrant activation of this pathway leads to the accumulation of β–catenin in the nucleus (Dai et al. 2021).

In this study, we demonstrated that SAG effectively suppresses the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in EBV-positive DLBCL cells by upregulating the expression of Axin and downregulating β-catenin and c-Myc, which are key components of the pathway. This suppression of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling likely contributes to the observed antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects of SAG.

In addition to directly modulating key components such as β-catenin and c-Myc, SAG may interact with upstream regulators or cofactors of the Wnt/β–catenin pathway, such as GSK-3β or APC, which are crucial for pathway regulation. While this study focuses on the downstream effects of SAG, its ability to upregulate Axin suggests potential involvement in stabilizing the β-catenin destruction complex.

The Wnt/β–catenin axis is not only crucial for normal cellular functions but also plays a vital role in DLBCL (Xing et al. 2024). In this context, the nuclear translocation of β-catenin and activation of its target genes lead to increased cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis (Xing et al. 2023). This study has shown that SAG can effectively counteract these processes in EBV-positive DLBCL cells by inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

Despite the promising findings of this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, our experiments were conducted in vitro, which may not fully replicate the complex interactions that occur in the tumor microenvironment in vivo. Therefore, future studies should include in vivo models to validate the therapeutic potential of SAG in DLBCL. Second, the precise molecular interactions between SAG and the Wnt/β–catenin axis require further investigation to fully elucidate the mechanisms through which SAG exerts its effects. Finally, exploring the potential synergistic effects of SAG in combination with existing DLBCL therapies could provide new avenues for enhancing treatment efficacy and overcoming resistance. It may be possible in the future to consider the use of biomaterials loaded with SAG to efficiently target tumors, given its toxicity. Of course, this needs to be confirmed by a large number of preclinical and animal experiments.

SAG may affect non-cancerous cells by targeting pathways that are not exclusive to malignant cells. This highlights the need for further studies to evaluate its selectivity and calculate the therapeutic index, ensuring that SAG’s anticancer effects can be maximized while minimizing potential off-target toxicity in normal tissues.

In conclusion, SAG has significant anticancer potential against EBV-positive DLBCL. By targeting the Wnt/β–catenin axis, SAG effectively inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in DLBCL cells.