In the past three decades, high-throughput technologies have added unprecedented insights into the cancer genome [1,2]. Cellular phenotypes, interactions, communications, and spatial organizations are central in assessing multi-dimensional aspects of carcinogenesis and metastasis. The evolution of drug resistance greatly confounds the efficacy of targeted therapies in cancer treatment. Tumors comprise many different cell types organized in spatially structured arrangements, with intra-tumor and inter-tumor heterogeneities [3,4]. Advancements in spatial profiling technologies have unraveled the intricacies of these cellular architectures to build a holistic view of the convoluted molecular mechanisms that shape the tumor ecosystems [5].

Nutrigenomics has gained phenomenal momentum because of rapidly accumulating concrete evidence about the pivotal role of dietary agents in disease prevention [6,7]. Emerging cutting-edge nutrition research has started to improve precision in nutrition [8]. We have witnessed phenomenal strides in our understanding of the anticancer and anti-metastatic roles of dietary agents. A wealth of information has highlighted the mechanistic role of dietary agents in the inhibition of proliferation, cancer drug resistance, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and metastatic dissemination.

Kiwifruits exhibit anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory [9], anti-diabetic [10,11], antimicrobial, antihypertensive [12,13,14], anti-hypercholesterolemic [15,16,17,18,19], and neuroprotective [20, 21] properties while promoting gut health. They are rich in primary and secondary metabolites and are a potentially functional food rich in organic acids, vitamins, calcium oxalate, carotenoids, anthocyanin, stilbenoids, and flavonoids.

There are some excellent reviews related to the pharmacological properties of kiwifruit [22, 23]. However, we have exclusively focused on the pharmaceutically tractable protein targets of extracts and bioactive constituents of kiwifruit in different cancers.

We partition this multi-component review into kiwifruit’s regulation of NOTCH signaling, ubiquitination, and ER stress. We also provide a summary of kiwifruit’s role in regulating non-coding RNAs.

Recent advancements have momentously refined our understanding of the VEGF/VEGFR signaling web in the progression of cancer [24,25,26]. Total Saponin from the Root of Actinidia valvata Dunn profoundly reduced invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Total saponins reduced microvessel densities, downregulated VEGF and bFGF, and impaired angiogenesis. More importantly, total saponins proficiently reduced the number of pulmonary metastatic nodules in mice injected with H22 cells [27].

VEGFA binds primarily to VEGFR2 (tyrosine kinase receptor) and fuels endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and sprouting. Extracts of the roots of Actinidia eriantha Benth downregulated the levels of VEGFA and VEGFR2 in HUVECs. Extracts also considerably reduced the formation of blood vessels in chick embryos [28].

Exciting evidence suggests that VEGFR-mediated signaling leads to the activation of Src. Moreover, SRC has also been shown to phosphorylate VEGFR2, thus initiating downstream signaling. SRC also phosphorylates FAK (Focal-adhesion kinase). Corosolic acid reduces the migratory potential of Huh7 cells by inhibiting the activation of VEGFR2. Corosolic acid reduces the phosphorylation level of VEGFR2 (Tyr-1058), non-receptor tyrosine kinase, Src (Tyr-416), and FAK (Tyr-397). Intraperitoneally administered corosolic acid-induced regression of the tumor mass in NOD/SCID mice injected with Huh7 cells. Corosolic acid reduces the phosphorylation of VEGFR2 and FAK in HCC xenografted mice. Corosolic acid binds to the ATP-binding pockets within the kinase domain of VEGFR2 [29].

Overall, these findings suggested that kiwifruit efficiently inhibited VEGFR-driven downstream signaling and angiogenesis.

Prostaglandin E receptor 3 (EP3) is frequently overexpressed in HCC. Moreover, EP3 promoted invasive properties of HCC cells mainly through an increase in the levels of VEGF, EGFR, MMP2, and MMP9. Actinidia chinensis Planch root extract effectively reduced the levels of EP3, VEGF, EGFR, MMP2, and MMP9 [30]. However, these aspects need detailed analysis in animal model studies. Comprehensive analysis of EP3 overexpressing-HCC cells in immunocompromised mice will generate valuable information.

Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) can inhibit metastatic spread of HCC cells. The ethyl acetate fraction of Actinidia callosa significantly enhanced the levels of TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 but simultaneously suppressed the levels of MMP2/MMP9 in SK-Hep1 cells. Furthermore, extracts also reduced the levels of PI3K and p-AKT levels [31].

Misfolded proteins gradually accumulate in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), leading to ER stress, thus causing activation of unfolded protein response (UPR) for the restoration of protein homeostasis [32,33,34]. The mitochondrial serine/threonine kinase PINK1 (PTEN-induced putative kinase 1) has been shown to phosphorylate Parkin (ubiquitin ligase). In cells with healthy and functionally active mitochondria, PINK1 is degraded promptly, and parkin remains in a state of auto-inhibition within the cytoplasm. However, when there is mitochondrial damage, PINK1 stabilizes on the mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) and triggers parkin activation [35, 36]. Importantly, Parkin regulates the assembly of the ubiquitin chains on different MOM proteins to facilitate the recruitment of ubiquitin-binding autophagy receptors.

2α,3α,24-Thrihydroxyurs-12-en-28-oicacid (TEOA) isolated from the roots of Actinidia eriantha has been found to be efficient against different cancers. TEOA, a pentacyclic triterpenoid, increased the levels of LC3-II and p62 (hallmarks of autophagy) in SW620 cells. TEOA dose-dependently enhances GRP78, p-PERK, p-elF2a as well as CHOP. Moreover, TEOA also induces an increase in the levels of Parkin and PINK1. Intraperitoneal administration of TEOA significantly suppressed tumor growth in mice xenografted with SW620 cells [37].

2α, 3α, 24-thrihydroxyurs-12-en-24-ursolic acid (TEOA) has been found to be effective against oral cancer. It has been shown to work effectively with chemotherapeutic drugs. TEOA and cisplatin-induced apoptotic death in oral cancer cells [38].

Non-coding RNAs have also revolutionized our knowledge of cancer biology, and it is now known that miRNAs considerably modulate wide-ranging target genes [39,40,41]. The complexity of intricate miRNA networks has reconceptualized the field of molecular oncology as miRNAs, produced from what was once considered “genomic trash,” have been shown to regulate cancer drug resistance, progression, and metastatic dissemination.

Radix Actinidiae extract has been shown to inhibit the expression of oncogenic miRNAs. Extracts induced suppression of miR-205-5p and inhibited the invasion of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells [42].

Actinidia chinensis root extract inhibits E2F1-mediated upregulation of oncogenic MNX1-AS1 in hypopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Intragastrically administered Actinidia chinensis root extract induced shrinkage of the tumors in mice subcutaneously injected with FaDu cells [43].

Adjuvants are quintessential components of rationally designed novel vaccines, having the unique ability to elicit humoral immunity and simultaneously induce efficient cell-induced immunity, including cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. Effective mobilization and recruitment of innate immune cells into the injection sites is an essential determinant of the efficacy of adjuvants. Long intergenic noncoding RNA associated with activated macrophage (linc-AAM) has been shown to trigger levels of immune response genes. It has been shown that linc-AAM interacted with hnRNPL (heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L) mainly through two CACACA motifs and caused its detachment from histone H3 to stimulate transcriptional upregulation of IRGs. NFκB p65 transcriptionally induces the expression of linc-AAM in macrophages [44].

Actinidia eriantha polysaccharide (AEPS) considerably increased interleukin-10, CCL2, TNFα, and CXCL10 in the peritoneal fluid of wild-type mice. However, a deficiency of linc-AAM notably inhibits the induction of these cytokines and chemokines in the peritoneal cavities of animal models treated with AEPS. It is also relevant to mention that AEPS remarkably induces the recruitment of dendritic cells, monocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, and mast cells into the peritoneal cavities of wild-type mice. However, loss of linc-AAM significantly suppresses these immune cells’ recruitment into the animal models’ peritoneal cavities. Moreover, the migration rate of the immune cells to draining lymph nodes is also impaired in linc-AAM deficient mice. There was a significant decline in the proliferation of splenocytes and natural killer cell functions in linc-AAM−/− mice compared to wild-type mice [45].

Seminal studies have highlighted the central role of non-coding RNAs in regulating carcinogenesis and metastasis. However, there are visible knowledge gaps in our understanding of the role of kiwifruit in regulating microRNAs, lncRNAs, and circular RNAs. There is a need to comprehensively characterize different subsets of non-coding RNAs likely to be regulated by kiwifruit. Accordingly, these findings will enable us to identify the mechanistic role of the most relevant non-coding RNAs in tumor inhibition in xenografted mice treated with extracts/bioactive constituents of kiwifruit.

Radix Actinidiae chinensis induced an increase in the levels of apoptosis-related proteins. There is a significant decline in the levels of p-PI3K, p-AKT, and p-mTOR in renal cell carcinoma cells [46]. Actinidia chinensis Planch root extracts also efficiently inhibited AKT/mTOR pathway in HepG2 and LM3 cells [47].

Extracts of Actinidia chinensis Planch root also inhibited invasion and metastasis of HCC cells. TARBP2 (TAR (HIV-1) RNA binding protein-2) has an oncogenic role in HCC cells. DLX2 (Distal-less homeobox) acts as a transcriptional factor and stimulates the expression of TARBP2 in HCC cells. JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) activates AKT in TARBP2, overexpressing HCC cells. However, extracts efficiently impaired DLX2-mediated activation of TRBP2 and JNK/AKT pathway in HCC cells [48].

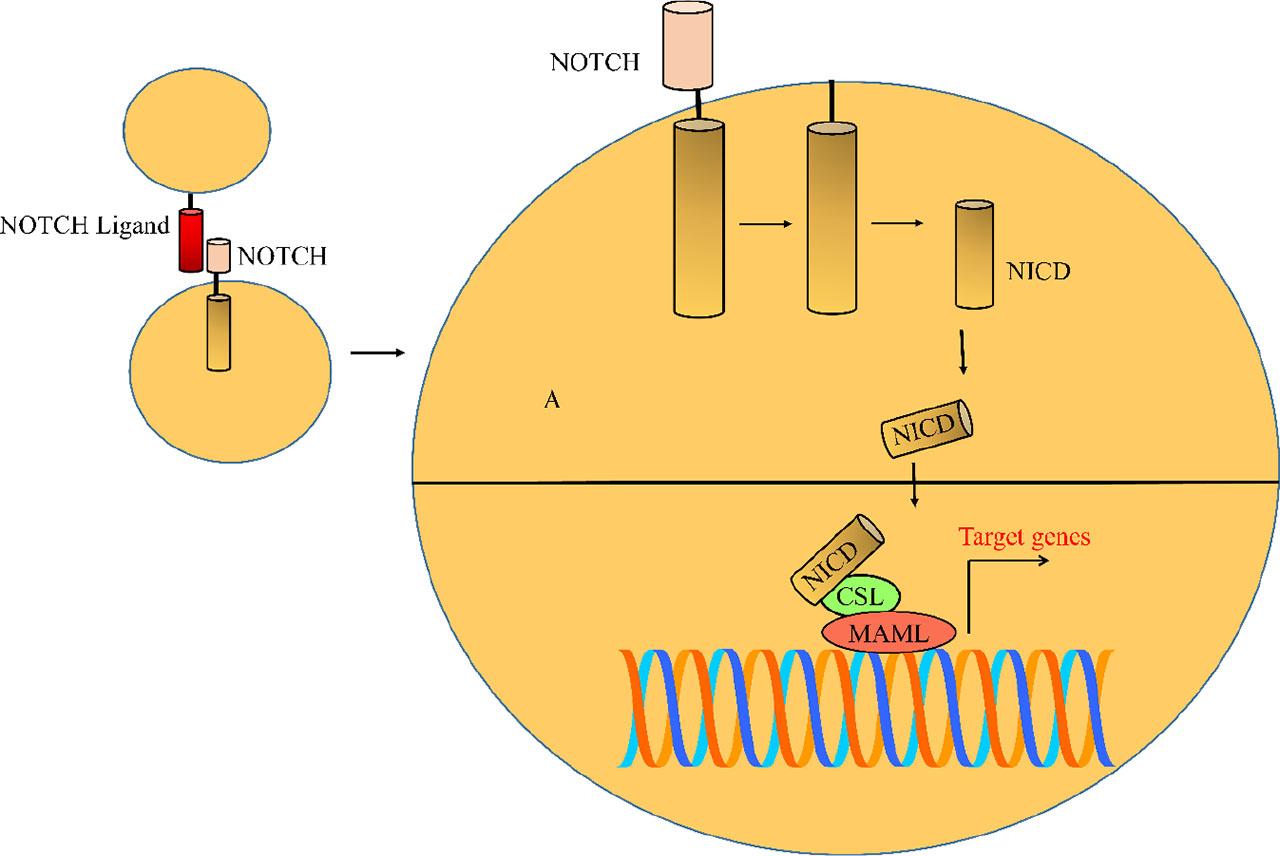

NOTCH ligands (Delta-like (DLL) and Jagged) initiate NOTCH signaling by triggering the proteolytic cascade of NOTCH receptors and subsequent release of active NICD (Figure 1). Upon activation of NOTCH signaling, NICD moves into the nucleus and forms a complex with a CSL-repressor complex, displaces the co-repressors, and promotes the recruitment of co-activators (MAML) for the stimulation of target gene networks [49,50,51,52].

NOTCH ligands (Delta-like (DLL) and Jagged) initiate NOTCH signaling by triggering the proteolytic cascade of NOTCH receptors and subsequent release of active NICD

Ethanolic extracts of radix of Actinidia chinensis considerably reduced the levels of Jagged1 and NOTCH1 in the tumor tissues derived from HT29 cells [53]. Moreover, ethanolic extracts also effectively suppressed DLL4, NOTCH1, and HES in SW480 cells [54].

NOTCH-CSL-MAML1 core complex is a multi-component machinery and serves as an initial scaffold on which transcriptional regulatory complexes are built. Therefore, because of the milieu of transcriptional regulatory proteins, different NOTCH assemblies can interact or recruit different proteins that mediate the transcriptional activation of NOTCH target genes.

TAM receptors (AXL) have been found to be involved in regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition, immune modulation, proliferation, angiogenesis, and resistance to targeted and conventional therapies. Vitamin K-dependent protein-ligand GAS (growth arrest-specific protein 6) activates AXL-driven intracellular signaling. Deregulation of AXL has been frequently noted in glioblastoma. Corosolic acid, a biologically active molecule isolated from Actinidia chinensis has been found to be efficient against glioblastoma. CHIP (carboxyl terminus of HSC70-interacting protein), a ubiquitin E3 ligase, tags ubiquitin moieties to AXL, thus causing its proteasomal degradation. Corosolic acid also reduces the levels of GAS and inhibits the invasion and migration of glioblastoma cells by inactivation of GAS/AXL signaling. Findings also suggested that corosolic acid markedly suppressed the phosphorylated levels of JAK2, MEK, and ERK in glioblastoma cells [55].

Plant-derived extracellular vesicles are phenomenal biological nanovesicles with astonishing biological functions. These nanovesicles have gained appreciation because of their features to escape from degradation by gastrointestinal fluids and their promising ability to cross the intestinal epithelial barriers. Encapsulation of sorafinib with kiwifruit-derived extracellular vesicles sufficiently enhanced the sustained release of sorafinib. Encapsulated sorafinib induced significant shrinkage of the tumors in mice orthotopically implanted with HepG2 cells mainly because of prolonged blood circulation time that passively increased the accumulation of sorafinib at the tumor sites [56].

Kiwifruit has high nutritional and medicinal values, and data obtained through different cellular studies emphasizes different biological and cellular mechanisms. However, we still have an insufficient understanding of the detailed mechanistic insights related to its tumor growth inhibitory activities. There are some outstanding questions that need to be addressed. Kiwifruit-mediated regulation of apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis needs further research. Apoptotic pathway is extensively explored in different cancers, and it will be intriguing to see how Kiwifruit modulates the intricate balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins in resistant cancer cells.