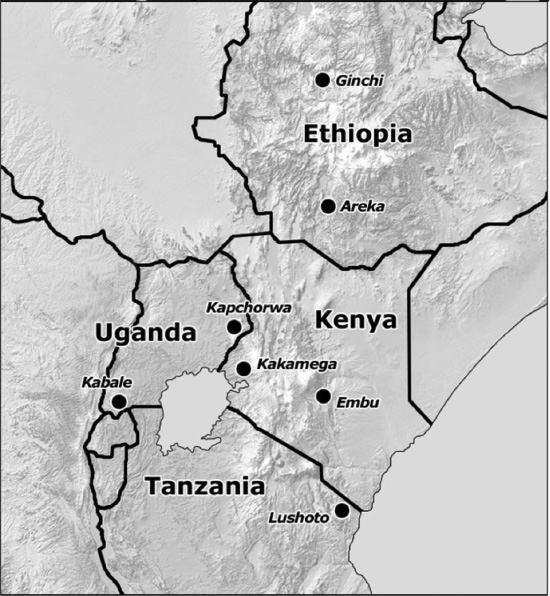

Figure 1:

Focal countries and AHI benchmark sites.

Table 1:

Relationship between facilitation steps and Ostrom’s design principles.

| Design principle | Facilitation step(s)/technique(s) | Explanation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: | Boundaries (emphasis on boundaries of users) | Identification of “stake”-holders, or those with divergent interests vis-à-vis the issue at hand | While distinctive in form from the Ostrom principle, the purpose is the same: to identify those individuals whose involvement is needed to address the issue at hand. | |

| 2: | Congruence (emphasis on appropriation and provision) | Stakeholder analysis (Who gains/loses what?) | Each of these steps is designed to match the benefits to any given party with the costs to that party. Stakeholder analysis enabled the identification of who gains and loses what from the status quo, and from any effort to address the problem. Stakeholder consultation aims to minimize the perceived risks of engaging in voluntary negotiations, for example by agreeing on procedural elements or establishing principles or criteria to guide negotiations. Negotiations themselves, guided by the principle of minimum harm, aim to balance the costs and benefits of action by mitigating harm done (e.g. through efforts to mitigate the costs of curtailing certain land uses); balancing concessions or provisioning with anticipated benefits; or allocating the costs of provisioning (often in the form of labor) to those standing to benefit from that action. Note: Each of these actions also contributes to aspects of principle 2A (congruence of costs and benefits with local social conditions). | |

| − | Stakeholder consultation | |||

| − | Negotiation support to identify institutional and technological solutions (by-laws, cost minimization efforts) | |||

| 3: | Collective choice arrangements | − | Negotiation support (negotiated rule formulation) | Similar to the Ostrom principle, the idea is to have all of those affected by the operational rules to participate in formulating them. |

| 4: | Monitoring | − | Monitoring plan included as one output of the negotiation | As with Ostrom, emphasis is placed on compliance with agreed actions (monitoring of users). It also emphasizes effectiveness in resolving the problem, yet this is not always defined in terms of resource condition; another common indicator was the mitigation of livelihood costs. |

| 5: | Graduated sanctions | − | Negotiation support (negotiated rules on consequences for non-compliance, and means of enforcement) | The negotiation of rules includes the negotiation of consequences for non-compliance. The negotiation process also involves forging agreement on the means of enforcement – whether through formal state recognition of formulated by-laws, or self-enforcement. The participatory nature of this process in some cases gives rules and/or their enforcement a ‘graduated’ character – with sanctions or enforcement procedures adapted to the circumstances at hand. |

| 6: | Conflict resolution mechanisms | − | Stakeholder analysis | Unlike Ostrom’s principles, conflict resolution was integrated into the process as a means of enabling the emergence of collective action during the planning process (in the stakeholder analysis and negotiation support stages), rather than something that comes afterwards. Nevertheless, such mechanisms are likely to evolve as part of the monitoring process. |

| − | Negotiation support | |||

Table 2:

Collective action dilemmas present in AHI benchmark sites.

| Identified concern | Country | Nature of the dilemma |

|---|---|---|

| Common pool resource challenges | ||

| Loss of indigenous tree species | Ethiopia (Ginchi) | Failure to adequately address the exclusion problem, coupled with the institutional uncertainties associated with periods of institutional uncertainty associated with regime change (feudal to socialist to capitalist), have led to loss of all indigenous trees outside of protected areas and sacred forests |

| Low soil fertility in outfields | Ethiopia | Seasonal transitions between private cropland and open access grazing in outfields induces nutrient mining by incentivizing landowners to extract all crop residue before liberating private cropland for communal grazing. Absence of institutions to regulate dung collection and the use of dung as cooking fuel exacerbates this by encouraging dung extraction from outfields. |

| Loss of indigenous crop and fodder species | Ethiopia (Areka) | The combined effects of drought and failure to regulate access to communal grazing areas has resulted in the loss of indigenous fodder species important to livestock. Absence of collective in-situ conservation of indigenous landraces, valued for their greater adaptability to suboptimal growing conditions, has contributed to their loss in the face of government extension services and food insecurity (seed consumption). |

| Declining water quality in springs | Ethiopia (Ginchi) | Failure to regulate use among users and by livestock undermines water quality by failing to separate drinking areas for livestock and human use. |

| Ineffective regulation of access to protected areas | Ethiopia, Uganda | Local land users have no incentive to invest in a resource that they have been excluded from, yet the state has limited capacity (and incentive) to exclude – resulting in state-induced “tragedies”*. |

| Low investment in the management of shared resources | Tanzania | Collective action surrounding shared resources (community bull, maintenance of community roads and schools, mill) suffers from low levels of provisioning*. |

| Theft of trees from village woodlots | Tanzania | Constraints to, and high cost of, exclusion; failure to adequately curtail free riding*. |

| Inefficiencies of individualized action | ||

| Pest management | Ethiopia, Tanzania | – Individualized efforts to police fields at night to avoid crop loss from porcupine is costly (in time, health consequences) and often ineffective as porcupines travel up to 14 km in a night (Areka). |

| – Erosion of traditional ecological knowledge among the youth has reduced collective action in pest control, undermining the effectiveness of these practices and contributing to the incidence of cutworms (Tanzania). | ||

| Shortage of oxen | Ethiopia (Ginchi) | Private ownership of oxen makes access to draft power inaccessible for most families; collective ownership and use was seen as a possible solution. |

| Externalities | ||

| Loss of seed and fertilizer, destruction of property, from excess run-off | Ethiopia, Tanzania, Uganda | Limited incentive to invest in drainage structures among upslope farmers (where water damage is less of a problem) exacerbates uncontrolled run-off to downslope farmers. Addressing the problem requires the coordination of drainage among all landowners, even those with limited incentive to invest. |

| Reduced crop productivity from boundary trees | Ethiopia (Areka), Tanzania | Landowners’ interests in securing farm boundaries and minimizing competition between trees and their own cropland cause them to locate woodlots along their farm boundary, increasing tree-crop competition on adjacent farmland*. |

| Burial of fertile valley bottom soil from erosion | Tanzania | Advanced stages of erosion on upper slopes means that soil deposited in valley bottoms (where cash crops are grown) is now infertile. Addressing the problem requires the cooperation of owners of hillslope plots who stand little to gain, while scale-dependencies increase the magnitude of the challenge. |

| Crop destruction from stray fires and livestock | Tanzania | Failure of private landowners to invest in activities to ensure fire does not pass farm boundaries, and the costs (in labor, fodder access) of regulating livestock movement, increases the incidence of crop loss on neighboring farms*. |

| Drying of springs from fast-growing trees | Ethiopia, Tanzania | Landowners’ interest in maximizing yield from fast-growing trees by locating woodlots near springs conflicts with collective interests in safeguarding the water supply for humans and/or livestock*. |

| Externalities from trees marking protected area boundary | Tanzania | Eucalypts planted to clearly demarcate/safeguard the boundary of a national park generate externalities for neighboring communities, such as the drying of springs or competition with adjacent cropland*. |

| Pest management | Ethiopia (Areka) | Landowners growing crops not susceptible to vertebrate pest damage have limited incentive to invest in pest control, yet with pests crossing farm boundaries their failure to act has consequences for other land users. |

| Common interests in state or private property | ||

| Limited/inequitable access to resources from protected areas | Uganda | Indigenous communities evicted from a national park face the threat of physical violence when attempting to access culturally important resources, yet outsiders with no customary claims are able to secure access through bribes*. |

| Inequitable access to government extension services | Ethiopia (Areka) | Failure to establish institutions to self-govern exogenous development resources, coupled with the preference among extension agents to work with “innovative” male farmers, has resulted in elite capture of government extension by wealthy male farmers. |

| Pest management | Ethiopia (Areka) | Those with coveted knowledge on traditional pest management practices have no incentive to share their knowledge with others, as they are often paid to help others with pest control*. |

Table A1:

Ostrom’s design principles of long-enduring common property regimes, as modified by Cox et al. (2010).

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| 1A | User boundaries: Clear boundaries between legitimate users and nonusers must be clearly defined. |

| 1B | Resource boundaries: Clear boundaries are present that define a resource system and separate it from the larger biophysical environment. |

| 2A | Congruence with local conditions: Appropriation and provision rules are congruent with local social and environmental conditions. |

| 2B | Appropriation and provision: The benefits obtained by users from a common-pool resource (CPR), as determined by appropriation rules, are proportional to the amount of inputs required in the form of labor, material, or money, as determined by provision rules. |

| 3 | Collective-choice arrangements: Most individuals affected by the operational rules can participate in modifying the operational rules. |

| 4A | Monitoring users: Monitors who are accountable to the users monitor the appropriation and provision levels of the users. |

| 4B | Monitoring the resource: Monitors who are accountable to the users monitor the condition of the resource. |

| 5 | Graduated sanctions: Appropriators who violate operational rules are likely to be assessed graduated sanctions (depending on the seriousness and the context of the offense) by other appropriators, by officials accountable to the appropriators, or by both. |

| 6 | Conflict-resolution mechanisms: Appropriators and their officials have rapid access to low-cost local arenas to resolve conflicts among appropriators or between appropriators and officials. |

| 7 | Minimal recognition of rights to organize: The rights of appropriators to devise their own institutions are not challenged by external governmental authorities. |

| 8 | Nested enterprises: Appropriation, provision, monitoring, enforcement, conflict resolution, and governance activities are organized in multiple layers of nested enterprises. |