Table 1

Case study description.

| Case Studies | Alto y Medio Dagua and Bajo Calima (Colombia) | Santiago Comaltepec (Mexico) | Bahía Blanca (Argentina) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Chocó Biogeographic region→Pacific coast→ Buenaventura→Dagua and Calima Rivers’ basins | Mesoamerican biocultural region→State of Oaxaca→Sierra Norte de Oaxaca→Chinantla | Southwestern coast of Buenos Aires region→Bahía Blanca Estuary region and adjacent coasts |

| Population | AMDA: 1502 Afro-Colombian inhabitants spread across six villages BC: 3550 Afro-Colombian inhabitants spread across six villages | 1115 Chinantec inhabitants in a central nucleus (Comaltepec) and two agencies (La Esperanza and Soyolapam) | Approximately 100 artisanal fishers and 500 fisheries-dependent families. The area has 32,582 inhabitants in five urban centers |

| Area | AMDA: 12,335 hectares Calima: 77,724 hectares | 18,366 hectares | 230,000 hectares (estuary) |

| Livelihoods | AMDA: Agriculture, artisanal gold mining, and fishing. Incipient ecotourism initiatives Calima: Logging, artisanal gold mining, and fishing | Logging, subsistence agriculture, livestock, sawmill and ecotourism Payment for ecosystem services (water catchment) Remittances | Fishery for artisanal fishers. Other inhabitants depend on tourism, petrochemical industry, port, industrial fishery, livestock industry, fruit and vegetables |

| Socioeconomic features | High level of poverty and marginalization Lack of formal jobs Some job opportunities in cities, construction, infrastructures | High level of poverty Lack of employment opportunities Migration | High level of economic development Low unemployment level Diversified job structure, with artisanal fishery representing a small sector |

| Brief description of the SES | Tropical forest with high biodiversity and water resources Good road connections in AMDA (Buenaventura-Cali highway crosses the territory) but many settlements in Calima only accessible by boat Depletion of forest by a paper factory in the 1960s–1980s, now restored Armed conflict, paramilitaries and illegal activities | Temperate, mesophyll and tropical forests (the territory ranges from 200 to 3000 m.a.s.l.) Strong conservation values Depletion of forest by a paper factory in the 1960s–1980s, now restored. Important struggles to recuperate the use of forest Blocking of new initiatives and entrepreneurship Low provision of infrastructures and services at the two agencies | Important environmental and paleontological resources Strong urban influence Heterogeneous community in terms of natural resource use, power relations, conflicts Artisanal fishery considered as a non-efficient sector Disturbance of estuary ecological functions by economic activities Interferences in dune dynamics and coastal erosion by buildings |

| References | AMDA-CVC (2007) Farah et al. (2012) Calima-CVC (2008) | Chapela (2007) Escalante et al. (2012) INEGI 2010 | London et al. (2012) |

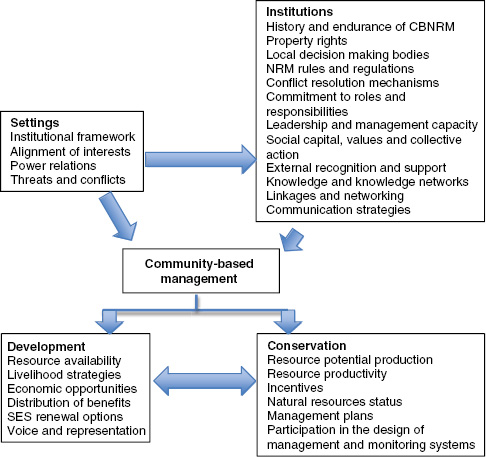

Figure 1:

Framework of analysis.

Source: Own elaboration based on Fabricius (2004), Fabricius and Collins (2007), Brondizio et al. (2009), Gruber (2010); Shackleton et al. (2010).

Table 2

Summary of data collection methods.

| AMDA-Calima | Comaltepec | Bahía Blanca | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workshops (N) | 6 (22 participants on average) | 6 (20 participants on average) | 6 (25 participants on average) |

| Interviews (N) | 10 | 6 | 8 |

| Participant observation | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Participant selection methods | Stakeholder mapping using knowledge of territory and forests and biodiversity management, legitimacy, local inhabitants and leadership as criteria | Stakeholder mapping using knowledge of territory and forest management, legitimacy, local inhabitants, and leadership as criteria | Stakeholder mapping using knowledge of territory and fishery management, legitimacy, local inhabitants and leadership as criteria |

| Timing | January 2012–December 2014 | January 2012–December 2014 | January 2012–December 2014 |

Table 3

Factors describing the settings.

| Calima and AMDA (CO) | Comaltepec (MX) | Bahia Blanca (AR) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional framework | Collective rights recognised by National Constitution | Collective rights recognised by Mexican Constitution Direct administration of the territory by local inhabitants recognized by state and federal laws | Marine and coastal resources are public property Fishing activities developed by private actors and regulated by government |

| Alignment of interests | Partial, conflict between conservation (Biodiversity Policy) and economic development interests (mining) | No current collision of interests between government and community | Lack of alignment between artisanal fishers and government interests in industrial sectors |

| Power relations | Highly asymmetric | Asymmetric | Asymmetric and not well-defined |

| Threats and conflicts | Paramilitaries and guerrilla Richness of natural resources attracts powerful actors | No external threats or conflicts Migration as internal threat | Different sectors compete for natural resource use |

Table 4

Factors describing institutions.

| Calima and AMDA (CO) | Comaltepec (MX) | Bahia Blanca (AR) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| History and endurance of CBNRM | Short history | Long history | Long tradition of artisanal fishers’ association but difficulties facing collective action |

| Property rights | Collective property of lands and natural resources, but minerals are state property | Collective ownership of lands and natural resources, but minerals are state property | Public ownership of natural resources but privately exploited following national rules |

| Local decision making bodies | General Assembly Rural neighborhood committees Sector committees Community leaders elected by the Assembly | General Assembly of Commoners Common Goods Commissioner elected by the Assembly Overseeing Council Council of Eldest (Caracterizados) with strong influence | Fishers associations have assemblies and design representatives, but have limited decision-making power to influence resource regulation |

| NRM rules and regulations | Internal Regulation and Management Plans Access and use rights but no monitoring or sanctions Social sanctioning but not always rule compliance No rule compliance by external actors Youths and women encouraged to get involved | NRM rules decided in the Assembly of Commoners Well-defined access, use, monitoring and enforcement rights Obligatory collective activities Social sanctioning Internal and external rule compliance Weak role of women and young | Government regulates access, monitoring and sanctioning rights Internal rules respected by fishers but not by external actors Rangers and police control fishery extraction Social sanctioning partially work among artisanal fishers but free-riding predominates in other collectives |

| Conflict resolution mechanisms | Internal conflicts: face-to-face External conflicts: environmental authorities | Face-to-face | Conflicts solved with demonstrations, strikes and road cutting, creating large economic losses |

| Commitment to roles and responsibilities | High commitment Leaders and managers remunerated based on the funds attracted to the territory | High commitment Pro-bono work by commoners | Moderate commitment |

| Leadership and management capacity | Strong and recognized leaders internally, but limited external influence High legitimacyNGOs and national agencies support in management tasks | Uncontested leadership of Caracterizados Management capacities developed by UZACHI, a technical organization hosted by four indigenous communities | Several fisher associations exist, weakening leadership and representation. Often, personal interests prevail over collective ones |

| Social capital, values and collective action | High bonding and bridging and limited linking social capital Collective action is part of people’s idiosyncrasy Legitimacy and trust values | High bonding, medium bridging and low linking social capital Assembly’s tight control on innovation and entrepreneurship Reciprocity, trust and legitimacy values | Medium bonding and linking and low bridging social capital. Individualistic and opportunistic behavior Local community involvement historically discouraged |

| External recognition and support | Rights of Afro-Colombian communities legally recognised, but no additional recognition | Closed community that does not foster external influences or external associations | Limited recognition of artisanal fishers but with a recent positive shift |

| Knowledge and knowledge networks | Collective knowledge transmission Learning activities | Customary knowledge transmission in the Assembly and the collective works | Limited knowledge transmission (fishing working conditions discourages younger generations) |

| Linkages and networking | Moderate | Limited (often based on community migrants) | Moderate in each town but limited between neighboring towns Networks created when environmental problems arise |

| Communication strategies | Well-developed internally, but not externally | Well-developed internally, but not externally | Lack of communication strategies and interaction spaces Local TV environmental program, with large audience and legitimacy |

Table 5

Factors describing conservation.

| Calima and AMDA (CO) | Comaltepec (MX) | Bahia Blanca (AR) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resource potential production | High | High | Could be higher if rules and regulations were respected |

| Resource productivity | Low-medium | Low | Decreasing fisheries’ productivity |

| Incentives | Links with nature Pride and self-esteem in having recognized rights to manage the territory Empowerment and capacity building linked to decision-making | Community values and believes, intimately linked to nature Legitimacy and reputationbased on collective dutiesaccomplishment Water catchment PES | Environmental problems lead to conservation initiatives |

| Natural resources status | Water pollution Riverbanks and habitats destruction Glyphosate aerial spraying Illegal logging and hunting Reforestation schemes | Biodiversity, natural habitats and water protected by community rules Forests restoration Management system certified as Smart and Sustainable Wood under FSC international standards | Changes in marine biodiversity Dunes affected by building activities Water pollution Dredging disturbs estuary New protection areas |

| Management plans | Ethno-development management plans | Forest management plans developed by UZACHI | No integrated management plans, but increasing demand to create them |

| Participation in monitoring systems | Community members report to authorities on illegal activities, but family ties prevent to reports on relatives’ activities | Community members monitor and patrol the territory | Regional and local authorities monitor. Fishers monitor, but have no enforcement authority |

Table 6

Factors describing development.

| Calima and AMDA (CO) | Comaltepec (MX) | Bahia Blanca (AR) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resource availability | Abundant | Abundant | Limited by poor management and lack of control |

| Livelihood strategies | Entire population relies on natural resource exploitation Hunting, fishing, agriculture and artisanal gold mining Legal and illegal wood commercialized with low added value | Entire population relies on natural resource exploitation Forest production, livestock and subsistence agriculture. RemittancesCommunal enterprises | Fishers’ livelihood strategies linked to natural resources, but other economic sectors exist |

| Economic opportunities | Few development opportunities and high levels of marginalization No formal jobs Armed conflicts undermined development possibilities No PES | Lack of economic opportunities and poverty Absence of qualified jobs force migration Communal enterprises provide (limited) jobs and incomes Lack of technology to add value to wood Emergent individual development initiatives (vegetables, orchids, and gourmet coffee) Water catchment PES | Job opportunities exist Good performance of socioeconomic indicators Ecological fish processing plant |

| Distribution of benefits | Community members individually profit from resources following the internal rules for extraction | Incomes from forest exploitation and communal enterprises not distributed to inhabitants | Benefits follow market principles Conflicts of interests between sectors |

| SES renewal options | High-medium | High | Highly dependent on environmental management. |

| Voice and representation | Limited externally, but Increasing All inhabitants have a voice in the Assembly | Limited (reduced interactions with other communities, rejection of new ideas and initiatives...) Restricted participation of youthand women in the Assembly | Increasing voice and representation of artisanal fisherseduced interactions with other communiti New interaction spaces that increase collective action |