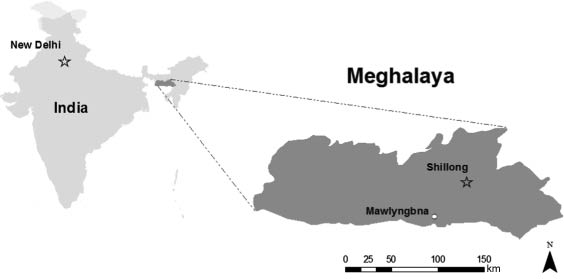

Figure 1

Location of the case study village Mawlyngbna.

Source: LaHaela 2013.

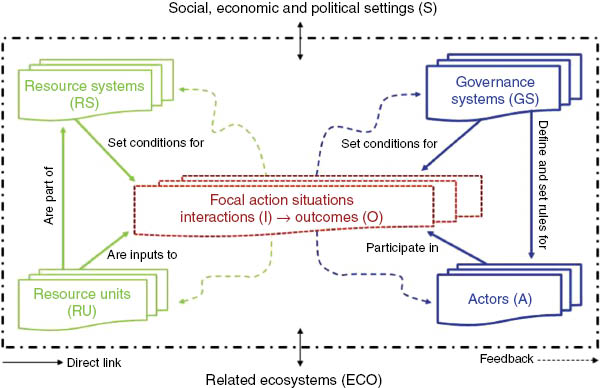

Figure 2

Revised social-ecological systems framework with multiple first-tier components.

Source: McGinnis and Ostrom 2014.

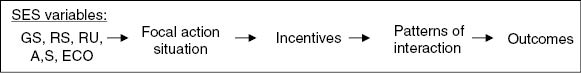

Figure 3

Explaining interactions and outcomes in SES.

Source: adapted from Gibson et al. 2005, 26.

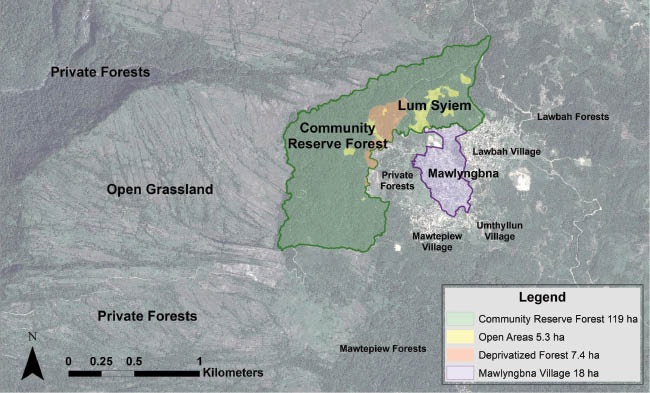

Figure 4

Land use map of Mawlyngbna.

Source: LaHaela 2013.

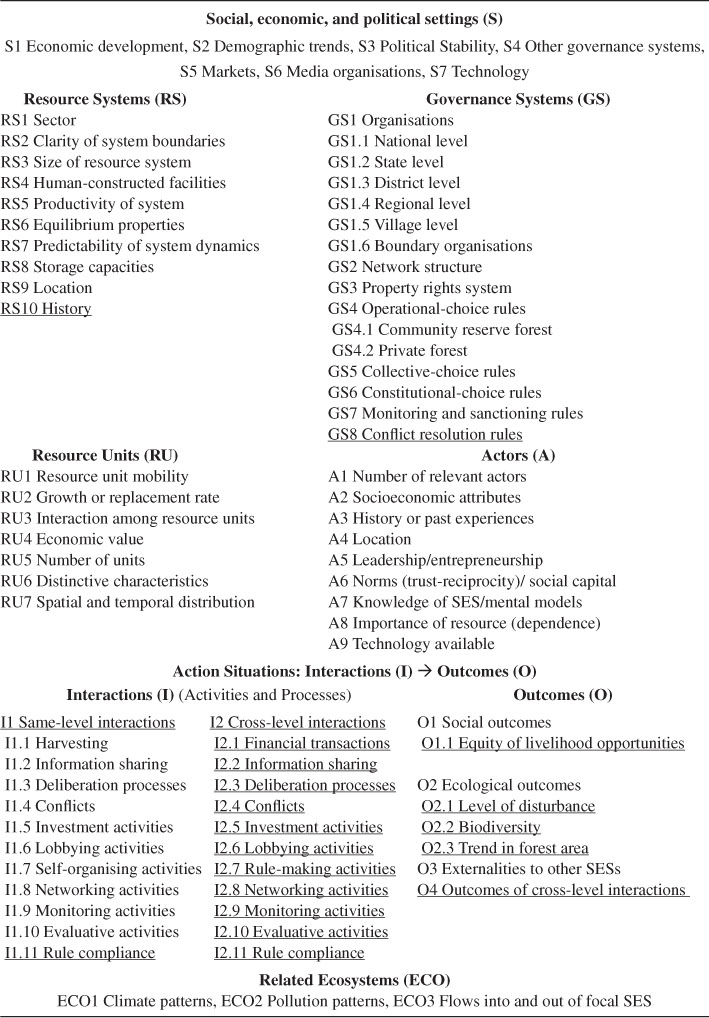

Table 1:

Coding scheme: second-tier variables of the SES framework (adapted from McGinnis and Ostrom 2014; underlined: added variables during iterative coding, cf. Section 5.3).

Table 2:

Structural and compositional parameter values for the mature tree life stage layer in the Community-Reserve Forest (CRF) and Private Forests (PF) and their α significance.

Source: LaHaela 2013.

| Parameter | CRF | PF | α Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total basal area (m2 ha–1) | 30.2 | 14.9 | α=0.05 |

| Average height (m) | 7.9 | 4.5 | α=0.007 |

| Average density (stems ha–1) | 1338 | 1344 | α=1 |

| Total stumps | 179 | 154 | n/a |

| Total basal area (m2 ha–1) of stumps | 9.4 | 8.9 | n/a |

| Disturbance index (%) | 17.7 | 39.0 | α=0.156 |

| Genera richness | 56 | 44 | α=0.070 |

| Number of families | 37 | 31 | α=0.026 |

| Shannon-Wiener’s diversity index (H’) | 2.60 | 2.22 | α=0.028 |

| Simpson’s dominance index (λ) | 0.07 | 0.13 | α=0.005 |

Table 3:

Opportunities and constraints of increased cross-level interactions.

| Possible partner | Opportunities | Constraints |

|---|---|---|

| Forest and Environment Department | High funding capacities | Low level of trust |

| High professional capacities | Legal preconditions | |

| Legal timber sale through ‘forest working plan’ | Potential dependence and autonomy constraints | |

| Party politics-driven | ||

| Khasi Hills Autonomous District Council | High level of trust | Low funding capacities |

| Contacts to FED | Party politics-driven | |

| Limited political influence | ||

| NGOs (e.g. Bethany Society, FES, Community Forestry International, IFAD) | Politically independent | Low political influence |

| Potentially high level of trust | ||

| High professional capacities |

Table 4:

The design principles of Ostrom (1990, 2010) for robust resource governance and assessment for Mawlyngbna’s forest governance

| Design principle | Description (cited from Ostrom 2010, 13) | Fulfilled in Mawlyngbna? |

|---|---|---|

| 1a User boundaries | Clear and locally understood boundaries between legitimate users and nonusers are present. | Yes. |

| 1b Resource boundaries | Clear boundaries that separate a specific common-pool resource from a larger social-ecological system are present. | Yes. |

| 2a Congruence with local conditions | Appropriation and provision rules are congruent with local social and environmental conditions. | Partially. The allowance to cut live trees in the CRF is not dependent on the ecological state of the forest resources. |

| 2b Appropriation and provision | Appropriation rules are congruent with provision rules; the distribution of costs is proportional to the distribution of benefits. | Yes. |

| 3 Collective-choice arrangements | Most individuals affected by a resource regime are authorized to participate in making and modifying its rules. | Partially. Only male adults can participate. |

| 4a Monitoring users | Individuals who are accountable to or are the users monitor the appropriation and provision levels of the users. | Partially. Only social control, no employed guards. |

| 4b Monitoring the resource | Individuals who are accountable to or are the users monitor the condition of the resource. | Partially. Only anecdotal observations and traditional knowledge, no employed guards. |

| 5 Graduated sanctions | Sanctions for rule violations start very low but become stronger if a user repeatedly violates a rule. | Yes. |

| 6 Conflict resolution mechanisms | Rapid, low cost, local arenas exist for resolving conflicts among users or with officials. | Yes. |

| 7 Minimal recognition of rights to organise | The rights of local users to make their own rules are recognized by the government. | Yes. |

| 8 Nested enterprises | When a common-pool resource is closely connected to a larger social-ecological system, governance activities are organised in multiple nested layers. | Currently few cross-level interdependencies (see Section 4.4). |

Table A1

| General Rules | |

| 1. | The Executive Committee of the MawsynramSyiemship grants access to use the land of Mawlyngbna. |

| 2. | Burning is prohibited on the land of Mawlyngbna. |

| 1. | Only residents of Mawlyngbna are allowed to use the CRF. |

| 2. | The following products are allowed to be extracted from the CRF without special permission: firewood, plant parts (including medicinal plants) but not the whole plant, and bay leaf tree seedlings (Cinnamomumtamala). |

| 3. | Firewood can only be collected for self use and to sell it in the Mawlyngbna market. |

| 4. | Collecting wild flowers is prohibited in the CRF. |

| 5. | Hunting of any kind of animal is prohibited in the CRF. |

| 6. | Stone mining is prohibited in the CRF. |

| 7. | Cattle grazing is permitted in the CRF. |

| 8. | Living trees of the CRF can only be cut for personal construction purposes and only after the approval of a written application by the Village Headman. |

| 9. | A service charge of Indian Rupees (INR) 50 applies per application to cut living trees of the CRF. |

| 10. | Cutting live trees can be only granted to married villagers and to families which have to arrange a funeral. |

| 11. | For the construction of wooden houses, an unlimited number of trees can be granted to be cut per person per year. |

| 12. | For the construction of cement houses a maximum number of 50 living trees can be granted to be cut per person per year. |

| 13. | In case of an emergency, the Village Council can decide to cut and sell live trees from the CRF in order to receive extra funds. |

| 14. | Only residents of Mawlyngbna are allowed to carry out the works such as tree cutting in the CRF. |

| 15. | CRF resources can only be sold at the market in Mawlyngbna. |

| 16. | In case of a fire threatening the CRF, each resident is obliged to help fight the fire. |

| 1. | Non-CRF land within the area dedicated to the Mawlyngbna residents can be claimed as private forest (PF). |

| 2. | If a piece of PF is not cultivated (i.e., no crops such as bay leaf trees or betel nut trees are growing on it) for at least three consecutive years it is open to be claimed by another Mawlyngbna villager. |

| 3. | The right of use of a PF patch can only be transferred amongst Mawlyngbna residents. |

| 4. | Except for burning, any form of use by the user is permitted in the PF. |

| 5. | The Village Council can levy a tax on sold cash crops extracted from PFs. |

| 6. | PF users can be expropriated of a certain PF patch if the Village Headman approves the application of another villager for constructing a house there. |

| 7. | Cash crop trees have to be compensated (INR 50 per tree). |

| 8. | The Village Council can decide to expropriate PF patches for development projects. |

| 9. | The Village Council can decide to expropriate PF patches and convert them into CRF. |

| 10. | The former user of converted PF is only allowed to harvest remaining crops (e.g., bay leaves or areca nuts) as long as the crop plants live but may not undertake any maintenance. |

| 11. | Any villager is allowed to quarry stone in any PF no matter if the villager is the “owner” or not. |

| 12. | The elimination of vegetation in PF for stone quarrying is permitted except for the crop trees and only after consultation with the “owner”. |