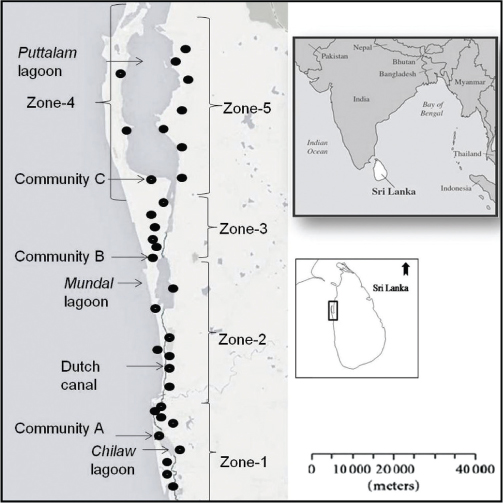

Figure 1

Study area: Three coastal communities (A, B, and C), and the distribution of communal institutions (community associations/samithis) in northwestern Sri Lanka.

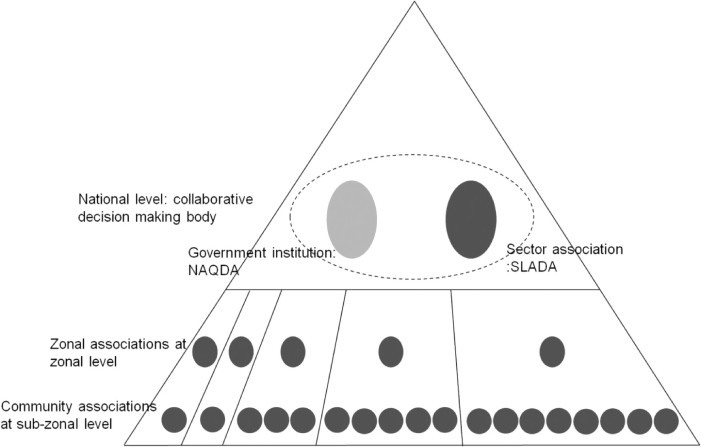

Figure 2

Multi-level governance structure of small-scale shrimp farming.

Table 1

Historical background: Use and management of the Dutch Canal.

| Prior to big aquaculture | During big aquaculture | Small aquaculture |

|---|---|---|

| Dutch Canal was made during the Dutch colonial period (1658–1795) for transportation of goods from western coastal areas to the Colombo port. It runs northbound from Kelani river in Colombo and drains off to Puttalam lagoon. It creates a common water body in the area by connecting Mundal and Chilaw lagoons. A system of streams and small waterways was also available in this area. There was not much government or public attention in managing the lagoon water or the Dutch Canal. | With the expansion of shrimp farming, Dutch Canal became the main brackish water source for aquaculture ponds. A canal system was constructed in the area for shrimp farming purposes by inter-connecting the small streams through canal branches. Few farmers also started farms (medium-scale) to produce shrimp for the large corporations. These farms collectively withdrew a large amount of water and discharged effluents at the same time. | A large number of small scale farms collectively created the demand for water. As discussed under the section on the zonal crop calendar system, shrimp farming cooperatives and the government collaboratively developed a calendar to manage the use of the water body using temporal and spatial boundaries. Rules were introduced and implemented by the community level cooperatives to control withdrawal of water and discharge of effluents, and not to mix the two. |

Table 2

Comparison of impacts: small-scale vs. large-scale.

| Concerns | Small-scale farms | Large-scale farms |

|---|---|---|

| Amount of waste water released to the environment (common water body) | Relatively low | Relatively high |

| Nature of waste water release | Small amounts of water intermittently | Large amount of water all at once |

| Environment’s ability to absorb the waste water from ponds | Relatively high | Relatively low |

| Economic loss due to disease conditions | Relatively low | Relatively high |

Table 3

Application of revised design principles for robust commons institutions and collective action (Ostrom 1990;Cox et al. 2010).

| Principle | Level of compliance with the principle | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1A: Clearly defined user boundaries | High | Zonal/sub-zonal boundaries:Zones and sub-zones are defined for resources management purposes. Clearly understood physical (rivers, canals, streams, etc.) as well as virtual boundaries (e.g. divisional secretariats – an administrative boundary) demarcate shrimp farming communities (sub-zones). Shrimp farmers belonging to a community should not take water from the common water body in another community. Non-shrimp farming communities also exist as neighboring communities (if there is no water supply for them to engage in shrimp farming). |

| 1B: Clearly defined resource boundaries | High | Resource boundaries are same as user boundaries. |

| 2A: Congruence between rules and local conditions | High | Crop calendar:Shrimp farmers are allowed to take water from the common water body only during a certain period of the year based on a collectively agreed/developed crop calendar.Better management practices:Rules/guidelines related to better management practices in shrimp farming are formulated by the government institution and are adapted at the community level. |

| 2B: Proportional equivalence between costs and benefits | High | Costs and benefits managed via community associations:Membership of a community association comes with financial and non-financial costs and benefits coordinated through the community association. (Costs include membership and pond licensing fees; fines (if applicable). Benefits include access to information; free laboratory testing of samples; partial compensation for financial losses, subsidies for disinfectants. |

| 3: Collective-choice arrangements | High | Shrimp farmers’ associations:At national level, all the community associations collectively participate in designing the annual crop calendar. At community level, members of the community association collectively participate in designing/modifying their daily operational rules/procedures. |

| 4A: Monitoring rule enforcement | High | Community association and government institution:Farming operations are monitored throughout the culture cycle. This is done by the officers of community associations with the support of the government extension officers. |

| 4B: Monitoring state of resources | Moderate | External government institutions:Water quality of the common water body is monitored by government institutions (other than NAQDA).The common water body is monitored mainly by shrimp farmers themselves. Thirty-nine percent of the farms are family owned businesses; farmer and family members constantly observe changes taking place in shrimp ponds indicating disease. |

| 5: Graduated sanctions | Moderate | Community association (depending on the seriousness of violation):Minor: ignorance or violation of rules related to better management practices can result in fines and/or non-issuance of the permit for a particular season. Very serious: legal actions are taken if used water from a disease-infected pond is released to the common water body. |

| 6: Conflict resolution mechanisms | Moderate | Community association:Community association is the entity resolving the conflicts related to the common water body. Inter-community conflicts can go up to zonal or national level association(s). Issues are openly discussed during meetings to help resolve conflicts. |

| 7: Minimal recognition of rights to organize | High | Collaborative decision making and bottom-up approach:Shrimp farmers and the government collaboratively work in making decisions. Government institutions do not challenge the community associations or the community rules. The Fisheries Act of Sri Lanka recognizes and promotes a bottom-up approach in managing the sector. |

| 8: Nested enterprises | High | Multi-level institutional structure:Horizontally and vertically integrated institutions exist, mainly for decision making and information sharing purposes. |