Elinor Ostrom’s Governing the Commons (Ostrom 1990) celebrated its 20th anniversary in 2010. Since its appearance, the book has changed the agenda of commons research and practice. True to its title, it has sparked a search for ways to actually govern the commons – rather than simply declaring them anachronisms, for which there is no place in a world that looks to develop sustainably. Additionally, whereas since 1968 the commons debate was dominated by the ideas of one biologist, Governing the Commons opened up the quest for further understanding of commons questions to a great many other disciplines. In this special feature project we have sought to emphasize both aspects of the impact of the book.

1. From deconstructing to governing the commons

Between 1968 and 1990, Garrett Hardin pretty much set the agenda of commons management practice and – to a somewhat lesser extent – scholarship. This agenda emphasized deconstructing rather than governing the commons – proposing and actively working to convert common pool resources (CPRs) into either private or public goods, instead. Numerous cohorts of practitioners were trained according to the gospel of Hardin: Barrett and Mabry (2002) find that the Tragedy of the Commons (Hardin 1968) is the article that American biologists consider to have had the greatest impact in their career training. Apart from a small but growing niche of commons scholars (Ciriacy-Wantrup and Bishop 1975; McCay and Acheson 1987; National Research Council 1986; Van Laerhoven and Ostrom 2007), the academic debate on CPRs during this era did mostly not accept – or even was not willing to consider – the fact that under certain conditions groups of individuals can sustainably govern a commonly held resource. For example, around the time that Elinor Ostrom’s Governing the Commons appeared Colin W. Clarke – in an otherwise reasonably sophisticated survey of resource economics – labelled common ownership of resources as one of the fundamental anti-sustainability biases (Clarke 1991, 321).

Two decades after the publication of Governing the Commons, it has become accepted wisdom that under certain circumstances communities are able to govern CPRs on their own, without intervention of the state and without having to privatize the resource. At the research frontier the goal is no longer to prove that Hardin was wrong, but to determine the limits of self-governance of CPRs: exactly under which conditions would privatization be the best option and under which conditions would governments have to step in, for example, to enable the local community to work out their own governance system?

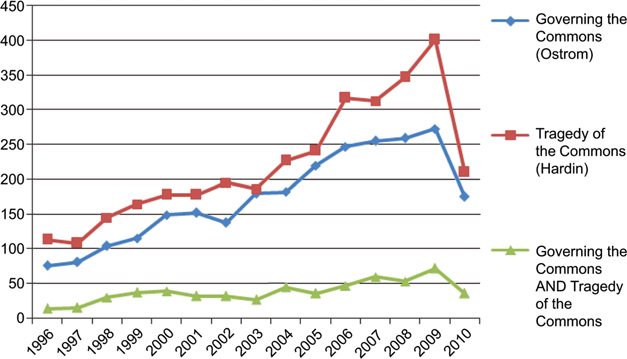

Our claim that Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons no longer holds a monopoly over the commons debate is illustrated by Figure 1. At least, since 1996 (the starting year in the Scopus data base used to build this figure) Governing the Commons offers a solid alternative to those interested in the sustainable governance of CPRs.

2. From one biologist’s idea to a truly interdisciplinary approach

However, the impact of Governing the Commons went much further than this. The book became a classic, more or less instantly. Since 1996, it has been cited in peer-reviewed journal articles that are indexed by Scopus2, no less than 2600 times. Many people besides resource governance scholars have read the book, and found inspiration for developing new ideas in seemingly unrelated fields. One may speculate why it had such a broad impact. Its immediate impact, particularly in resource economics, had a lot to do with its combination of game theoretical model-based arguments and empirical observations. The science was rigorous and the most critical readers had to conclude that the results were valid. But in order to understand the impact outside the circle of students of natural resource governance, we have to look beyond this obvious characteristic of the book.

According to a long-held, conventional view, there are private goods on the one end, and public goods on the other. This dichotomous view perceives the market as taking care of the provision, production and distribution of private goods – goods that are exhaustive and which can be fenced off from usage by those who do not pay for them. Citizens are consumers and the government has to step in every now and then, in order to correct market distortions (e.g. monopolies, externalities, and information asymmetries). The government is seen as being responsible for the delivery and allocation of public goods. These goods are not exhaustive and even those who have not contributed to (or paid for) their production, can still utilize and benefit from them. Citizens are constituents when dealing with public goods. The private sector is not supposed to be interested in public goods, since no money can be made from them. The perceived dichotomy was for long reflected in the disciplinary division of areas of interest: economists studied private goods, and public goods were examined by political scientists.

Ostrom’s work – her book Governing the Commons in particular – has challenged this view and the disciplinary consequences thereof. Solving problems in the public sphere in practice, it turns out, is not always the exclusive domain of governments. Citizens can be found to engage in self-organized forms of collective action with the purpose of providing and producing public goods or CPRs. Private-sector business actors initiate or participate in activities related to the creation of public goods and CPRs in ways that neither old-time economists, nor conventional political scientists would have held them capable of doing. More often even, problems in the public arena are resolved as the result of the interaction between multiple actors: government agents; civil society actors; and private sector entrepreneurs.

Governing the Commons provided an alternative analytical paradigm for the study of phenomena which previously were hard to understand. The book opened the way for a genuine inter-disciplinary approach to the solutions of problems related with the provision and production of public goods and CPRs. These solutions – in one way or the other – often come down to overcoming collective action dilemmas. Ostrom’s way of framing problems related with public goods and CPRs leaves ample room for the study of social systems – i.e. the behavior of people as individuals, as group members, as actors in a market setting or in a public economy, as administrators, as members of a civic society, as participants in a culture, etc. Her approach also allows for the involvement of students of ecological systems – i.e. the biophysical world that co-determines the very nature of the type of problems that the provision or the production of public goods or CPRs poses.

Since the publication of Governing the Commons, we find for example economists, sociologists, anthropologists, political scientists, legal scholars, geographers, biologists, ecologists, foresters, hydrologists, and students of public administration leaning on Ostrom’s work to craft their arguments with regard to their take on problem solving in the public sphere (Table 1). Furthermore, we find that peer-reviewed journals catering to audiences from an equally wide variety of disciplines have opened up to contributions representing Ostrom’s approach to Governing the Commons (Table 2).

Representatives from these disciplines were therefore not at all surprised to receive our invitation to participate in a special feature project on the impact of Governing the Commons. We provided our authors with one simple cue: what has been the meaning of Governing the Commons for your field of study? The first results of our ongoing project are presented in this journal issue. The exercise will come to a conclusion in the 2011 August issue of the International Journal of the Commons. Then we will also present an editorial synthesis of all the contributions.

Figure and Tables

Figure 1

Citation numbers for Governing the Commons (Ostrom) and Tragedy of the Commons (Hardin).

Table 1

(Co-) authors citing Governing the Commons (1996–2010).

| Name | # of GtC citations | Sub-affiliation | Affiliation | Country |

| Berkes, F | 16 | Natural Resources Institute | University of Manitoba | Canada |

| Folke, C | 16 | Stockholm Resilience Center, Dept of Systems Ecology | University of Stockholm | Sweden |

| Agrawal, A | 15 | School of Natural Resources and Environment | University of Michigan | USA |

| Dasgupta, P | 11 | Faculty of Economics and Politics | University of Cambridge | UK |

| Kant, S | 10 | Faculty of Forestry | University of Toronto | Canada |

| Platteau, JP | 10 | Dept of Economics | University of Namur | Belgium |

| Acheson, JM | 8 | School of Marine Sciences | University of Maine | USA |

| Andersson, K | 8 | Political Science Dept | University of Colorado | USA |

| Jentoft, S | 8 | Norwegian College of Fishery Science | University of Tromsø | Norway |

| Meinzen-Dick, RS | 8 | International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) | USA | |

| Pretty, J | 8 | Dept of Biological Sciences | University of Essex | UK |

| Baland, JM | 7 | Dept of Economics | University of Namur | Belgium |

| Bardhan, P | 7 | Dept of Economics | University of California at Berkeley | USA |

| Beard, VA | 7 | Dept of Planning, Policy and Design | University of California at Irvine | USA |

| Cardenas, JC | 7 | Dept of Economics | Universidad de los Andes | Colombia |

| Christie, P | 7 | School of Marine Affairs and Jackson School of International Studies | University of Washington | USA |

| Cinner, JE | 7 | Australian Research Council Center of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies | James Cook University | Australia |

| Dinar, S | 7 | Dept of Politics and International Relations | Florida International University | USA |

| Gintis, H | 7 | Dept of Economics | University of Massachusetts | USA |

| Paavola, J | 7 | School of Earth and Environment | University of Leeds | UK |

| Rydin, Y | 7 | Bartlett School of Planning | University College London | UK |

| Shivakoti, GP | 7 | School of Environment, Resources, and Development | Asian Institute of Technology | Thailand |

| Van Vugt, M | 7 | Dept of Psychology | University of Kent | UK |

| Weber, EP | 7 | Dept of Political Science | Washington State University | USA |

| Bowles, S | 6 | Behavioral Sciences Program | Santa Fe Institute | USA |

| Dayton-Johnson, J | 6 | Dept of Economics | Dalhousie University | Canada |

| Edwards-Jones, G | 6 | School of the Environment and Natural Resources | Bangor University | UK |

| Feitelson, E | 6 | Dept of Geography | The Hebrew University of Jerusalem | Israel |

| German, L | 6 | Forests and Governance Programme | Center for Internat. Forestry Research (CIFOR) | Indonesia |

| Gibson, CC | 6 | Dept of Political Science | University of California at San Diego | USA |

| Haller, T | 6 | Dept of Social and Cultural Anthropology | University of Zurich | Switzerland |

| Heikkila, T | 6 | School of Public Affairs | University of Colorado | USA |

| Hønneland, G | 6 | The Fridtj of Nansen Institute | Norway | |

| Hukkinen, J | 6 | Dept of Social Policy | University of Helsinki | Finland |

| Kaiser, MJ | 6 | School of Ocean Sciences | Bangor University | UK |

| McCarthy, N | 6 | International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) | USA | |

| Scholz, JT | 6 | Dept of Political Science | Florida State University | USA |

| Sell, J | 6 | Dept of Sociology | Texas A&M University | USA |

| Sikor, T | 6 | Faculty of Social Sciences | University of East Anglia | UK |

| Steins, NA | 6 | Marine Stewardship Council | Netherlands | |

| Tanner, S | 6 | Dept of Anthropology | University of Georgia | USA |

| VanDenBergh, J | 6 | Climate Change Research Network | Vanderbilt University Law School | USA |

| Adger, W | 5 | School of Environmental Sciences and CSERGE | University of East Anglia | UK |

| Brinkerhoff, JM | 5 | Dept of Public Administration | George Washington University | USA |

| Cleaver, F | 5 | Development and Project Planning Centre | University of Bradford | UK |

| Crona, BI | 5 | Stockholm Resilience Center | University of Stockholm | Sweden |

| DeCremer, D | 5 | Dept of Experimental Psychology | University of Maastricht | Netherlands |

| Edwards, VM | 5 | Dept of Land and Construction Management | University of Portsmouth | UK |

| Eggertsson, T | 5 | School of Business | University of Iceland | Iceland |

| Fernandez-Gimenez, ME | 5 | Dept of Forest, Rangeland, and Watershed Stewardship | University of Colorado | USA |

| Gardner, RJ | 5 | Dept of Economics | Indiana University | USA |

| Gelcich, S | 5 | School of Agricultural and Forest Sciences | University of Wales | UK |

| Imperial, MT | 5 | Dept of Public Administration | University of North Carolina | USA |

| Janssen, MA | 5 | School of Human Evolution and Social Change | Arizona State University | USA |

| Klooster, D | 5 | Dept of Geography | University of California at Los Angeles | USA |

| Koppenjan, JFM | 5 | Dept of Public Administration | Erasmus University | Netherlands |

| Kreuter, UP | 5 | Dept of Ecosystem Science and Management | Texas A&M University | USA |

| Lam, WF | 5 | Dept of Politics and Public Administration | University of Hong Kong | China |

| Lubell, M | 5 | Dept of Political Science | Florida State University | USA |

| Mahoney, JT | 5 | Dept of Business Administration | University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign | USA |

| Mandondo, A | 5 | Institute of Environmental Studies | University of Zimbabwe | Zimbabwe |

| Matsuda, Y | 5 | Dept of Marine Social Sciences | Kagoshima University | Japan |

| Nagendra, H | 5 | The Center for the Study of Institutions, Population, and Environmental Change (CIPEC) | Indiana University | USA |

| Pender, J | 5 | Economic Research Service | Department of Agriculture (USA Government) | USA |

| Peterson, GD | 5 | Dept of Geography and McGill School of the Environment | McGill University | Canada |

| Pomeroy, RS | 5 | World Fish Center | Malaysia | |

| Poteete, A | 5 | Dept of Political Science | Concordia University | Canada |

| Ray, I | 5 | Energy and Resources Group | University of California at Berkeley | USA |

| Reuveny, R | 5 | School of Public and Environmental Affairs (SPEA) | Indiana University | USA |

| Ribot, JC | 5 | Dept of Geography | University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign | USA |

| Robbins, P | 5 | EcoHealth Consulting | UK | |

| Ruttan, LM | 5 | Dept of Environmental Studies | Emory University | USA |

| Satria, A | 5 | Faculty of Human Ecology | Bogor Agricultural University | Indonesia |

| Schweik, CM | 5 | Dept of Environmental Conservation | University of Massachusetts | USA |

| Shrestha, KK | 5 | Nepal Agricultural Research Council | Nepal | |

| Squires, D | 5 | Southwest Fisheries Science Center | USA | |

| Tang, CP | 5 | Dept of Political Science | National Chung Cheng University | Taiwan |

| Webb, EL | 5 | Dept of Biological Sciences | National University of Singapore | Singapore |

| Wilson, RK | 5 | Dept of Political Science | Rice University | USA |

| Young, OR | 5 | Donald Bren School of Environmental Science and Management | University of California at Santa Barbara | USA |

Table 2

Journals citing GtC 10 times or more (1996–2010).

| Journal title | # of GtC citations | Current editor’s disciplinary background |

| World Development | 79 | Geography |

| Ecological Economics | 74 | Economics |

| Human Ecology | 65 | Anthropology |

| Ecology and Society | 60 | Ecology |

| Society and Natural Resources | 52 | Forestry |

| Marine Policy | 45 | Geography |

| Environmental Management | 27 | Ecology |

| Human Organization | 27 | Anthropology |

| Development and Change | 25 | Economics |

| Environment and Development Economics | 25 | Economics |

| Forest Policy and Economics | 24 | Economics |

| Ocean and Coastal Management | 24 | Biology |

| Journal of Environmental Management | 23 | Geography |

| Public Administration Review | 23 | Public Adm. |

| Conservation Biology | 20 | Biology |

| Environmental Conservation | 20 | Ecology |

| Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization | 19 | Economics |

| Journal of Development Studies | 16 | Geography |

| Land Use Policy | 16 | Geography |

| Environmental and Resource Economics | 15 | Economics |

| Geoforum | 15 | Geography |

| Policy Sciences | 15 | Policy Studies |

| Public Choice | 15 | Economics |

| Ambio | 13 | Biology |

| Journal of International Development | 13 | Sociology |

| Local Environment | 13 | Geography |

| Policy Studies Journal | 13 | Public Adm. |

| Global Environmental Change | 12 | Economics |

| Journal of Environment and Development | 12 | Sociology |

| Journal of Environmental Planning and Management | 12 | Economics |

| Coastal Management | 11 | Biology |

| Conservation Ecology* | 11 | n.a. |

| Environment and Planning A | 11 | Geography |

| Land Economics | 11 | Economics |

| Public Administration and Management | 11 | Public Adm. |

| Administration and Society | 10 | Public Adm. |

| Agricultural Systems | 10 | Economics |

| Ecological Applications | 10 | Ecology |

| Journal of Development Economics | 10 | Economics |

| Journal of Economic Issues | 10 | Economics |

| Journal of Sustainable Forestry | 10 | Forestry |

[i] *Appears currently as ‘Ecology and Society’.

Notes

[2] Berge started the work on this special feature while he was on the faculty of the Department of Sociology and Political Science at The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). The editors are grateful for the economic support from NTNU that made this special feature possible.

[3] www.scopus.com