The preference for similar others has been well documented by prior research with studies demonstrating that homophily—or, the increased prevalence of contact between similar people—is a driving force behind friendships in childhood and adulthood, romantic relationships, and even work-relevant collaborations (e.g., Ertug et al., 2022; Lincoln & Miller, 1979; Shrum et al., 1988; Watson et al., 2004; Wax et al., 2017). Prior researchers have discussed homophily as “a pervasive social fact” (Smith et al., 2014, p. 432), arguing that “[h] omophily limits people’s social worlds in a way that has powerful implications for the information they receive, the attitudes they form, and the interactions they experience” (McPherson et al., 2001, p. 415).

The majority of research on homophily has focused on visible, surface-level characteristics, such as sex or race (e.g., Smith et al., 2014; Twyman et al., 2022). In a comprehensive review of homophily in networks, McPherson et al. (2001) discuss that initial inquiries regarding homophily in social networks were concerned about surface-level characteristics (i.e., race, age, and sex). In contrast, the extant research on deep-level homophily has typically gravitated toward certain, specific, invisible characteristics, such as attitudes or values (e.g., Cunningham & Sagas, 2004). Based on the invisible nature of deep-level characteristics, it is important to understand how influential diversity or homophily of deep-level characteristics are compared to the visible surface-level characteristics within the work team context. In fact, the focus on surface-level characteristics has been a primary focus in team research as “the majority of team diversity research has focused on demographic characteristics” (Mohammed & Angell, 2004, p. 1018). However, Harrison et al. (2002) indicated that surface-level differences have more of an impact at early points in time, whereas deep-level differences matter more once individuals are well-acquainted with one another; in other words, surface-and deep-level characteristics do not seem to impact people in the same way, at the same time.

Moreover, it is important to consider the contextual factors and boundary conditions that impact homophily and resulting homogeneity. In certain scenarios, it is clear that group heterogeneity is preferable to homogeneity; for example, informational diversity has been shown to enhance team performance (e.g., Bernstein, 2016). For instance, for many complex tasks assigned to teams, the team is intentionally staffed with those who hold unique information that can contribute to a developed solution. However, very little research has been conducted to understand how deep-level characteristics drive interpersonal relationships among team members. Ultimately, more research is needed to comprehensively understand the factors that influence individuals’ willingness to engage in homophilous or nonhomophilous tendencies.

Adding further complexity, the world is becoming increasingly diverse and, while this has been a trend for some time, there is a need to understand the nuanced impacts of increased globalization. While early globalization primarily impacted business activities, such as trading, contemporary globalization shifted to impact interpersonal relationships also within the workplace (Gomathy et al., 2022). For instance, the amount of Japanese foreign workers has increased from 2010 to 2020 by 2.65 times and the amount of Japanese overseas workers has increased by 1.19 times (Isagozawa & Fuji, 2023; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2021; Ministry of Health, Labour & Welfare, 2021). In the Western world, the youngest generation—dubbed Gen Z or post-Millennials—is the most diverse one in history (Fry & Parker, 2018). This increase in globalization across nations indicates that employees will likely have increased opportunities to collaborate with diverse individuals, which introduces a variety of both surface-level and deep-level characteristics (Isagozawa & Fuji, 2023).

Accordingly, the current study seeks to reexamine the finding that homophily drives our relationships and extend the literature on the impacts of deep-level diversity on interpersonal relationships, by examining the relation between deep-level diversity and (a) social relationships, (b) task-relevant relationships, and (c) team performance. Restated, this stream of research aims to explore potential tendencies that people have to form relationships based on unseen similarities/differences, and to test whether those tendencies impact team performance.

Individuals categorize themselves and others into groups based on intragroup similarities and intergroup differences (Tajfel, 1982; Turner & Oakes, 1986), a process that has been likened to a lesser form of stereotyping (Allport, 1954). Self-categorization leads to the development of a social identity, or “that part of the individuals’ self-concept which derives from their knowledge of their membership of a social group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership” (Tajfel, 1981, p. 255). Members of the same social group—or, demographically similar individuals—tend to favor one another (e.g., Westphal & Zajac, 1995); in general terms, this preference for similar others is known as intergroup bias (Hewstone et al., 2002). In psychology, the preference for similar others is known as similarity-attraction. In network science, it is referred to as homophily.

The majority of the literature on interpersonal homophily and resulting patterns of homogeneity has focused on objective homogeneity, or the actual diversity of characteristics between people, regardless of whether these individuals are aware of their differences or not (Shemla et al., 2016). However, an emerging trend in the literature is to focus on perceived diversity, or the extent to which group members are aware of the variety of individual characteristics present within the group (Shemla et al., 2016). Based on the extant literature, it appears that–while perceptions of diversity may be related to important outcomes such as perceptions of organizational performance (Allen et al., 2008)–perceptions of diversity are commonly unrelated to objective measures of diversity (Hentschel et al., 2013; Ormiston, 2016). In other words, there is evidence to suggest that objective diversity and perceptions of diversity are fundamentally two separate constructs that are not closely interrelated, as one might expect them to be. That being said, perceptions of diversity may both moderate and mediate the relationship between objective diversity and team outcomes (Shemla & Wegge, 2019).

One theory of homophily posits that homophily can be categorized as surface-level and deep-level based on two types of individual attributes.

Surface-level homophily, on the one hand, is attraction based on similarities that are typically biologically rooted and that express themselves via physical features (Harrison et al., 1998). Sometimes called readily detectable or observable attributes, these are characteristics that can be detected quickly when perceiving another person (Jackson et al., 1995; Milliken & Martins, 1996). Common examples of surface-level attributes are age, gender, and race/ethnicity.

Deep-level attributes, on the other hand, are those that are not visible to the naked eye (Harrison et al., 1998), such as personality characteristics, beliefs, preferences, attitudes, values, and autobiographical experiences. Deep-level attributes are sometimes referred to as underlying or nonobservable attributes (Jackson et al., 1995; Milliken & Martins, 1996); in other words, the term “deep” is meant to imply that these types of attributes take more time to discern a person than surface-level attributes. Deep-level attributes can be both task-related (e.g., knowledge, skills, abilities) and relations-oriented (e.g., social status; Jackson et al., 1995; Milliken & Martins, 1996).

A core aspect of the definition of deep-level attributes is that they need to be communicated to be discerned by another person. This communication may be verbal in nature; for instance, as two people get acquainted with one another, they may share pieces of their autobiographical histories, giving one another access to their life experiences, a deep-level attribute. However, the communication of deep-level attributes may also be behavioral in nature. For example, a person who identifies as Christian may wear a cross on a necklace to indicate their religious affiliation, or a person who identifies as a member of the LGBTQIA+ community may wear a shirt with a slogan that indicates such. Both of these scenarios exemplify how people can communicate their deep-level attributes through their behavior.

Perceptions of similarity (and resulting attraction) can be based on virtually any surface- or deep-level individual difference, and drive the formation of both social and task-relevant relationships (e.g., Bacharach et al., 2005; Ruef et al., 2003).

People are often mutually attracted to one another based on the similarity of deep-level characteristics such as attitudes, personality, values, and beliefs (Lazarsfeld & Merton, 1954). Meta-analytic research has indicated that both actual similarity and perceived deep-level similarity are strongly related to interpersonal attraction (Montoya et al., 2008) and that the relation between similarity and attraction for deep-level characteristics is moderated by a variety of factors including the number of attributes that the judgment of similarity is being made on, the ratio of similar to dissimilar information, and information salience (Montoya & Horton, 2012).

The majority of research on deep-level similarity and attraction has focused on attitudes, which are valenced evaluations of objects (Breckler & Wiggins, 1989). For instance, people self-report feeling more attracted to (Byrne, 1961, 1971, 1997; Layton & Insko, 1974; Sachs, 1976; Wyant & Gardner, 1977; Smeaton et al., 1989; Singh et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2007) and even position themselves physically closer to (Allgeier & Byrne, 1973; Snyder & Endelman, 1979) attitudinally-similar others than attitudinally dissimilar others. This effect has been replicated in samples diverse in terms of age (Byrne & Griffitt, 1966; Singh et al., 2008a,b), educational level, socioeconomic status, intelligence, and mental health (Byrne et al., 1969). Furthermore, attitude similarity impacts attraction for a variety of different kinds of relationships, including friendships, work relationships, casual romantic relationships, and marriages (Black, 1974; Stroebe et al., 1971). Married couples tend to have similar attitudes toward religion (Watson et al., 2004), and both friends (Verbrugge, 1977) and married couples (Luo & Klohnen, 2005; Watson et al., 2004) tend to be similar with regard to political attitudes. Experimental research has demonstrated that political attitude similarity drives attraction, implying the direction of causality (Davis, 1981). Attitude similarity trumps other attraction-relevant information such as information on occupational prestige (Bond et al., 1968), and people may use other similarities—such as similarity in terms of race (Goldberg, 2005) or sexual orientation (Chen & Kenrick, 2002; Pilkington & Lydon, 1997)—as indicators of attitude similarity.

Other deep-level attributes upon which individuals are attracted to similar others include values (Davis, 1981; Luo & Klohnen, 2005; Watson et al., 2004), interests (Davis, 1981; Vandenberg, 1972), preferences (Jamieson et al., 1987), habits (Epstein & Guttman, 1984), and experiences (Pinel et al., 2006). Research has shown that Twitter users engage in assortative mixing based on similarity in subjective well-being—or, general happiness (Bollen et al., 2011). Additionally, similarity in subjective experiences is such a powerful attraction mechanism that it overshadows the potential repellant effects of superficially salient, surface-level differences between people (e.g., differences in race or gender; Pinel & Long, 2012).

In sum, research has reported that deep-level homophily drives the formation of relationships; this has been exemplified for homophily based on numerous different deep-level variables, as well as for many different types of relational outcomes. Keeping in line with these past results, we posit the following:

Hypothesis 1: Deep-level similarity will drive the formation of social ties in teams. Hypothesis 2a: Deep-level similarity will drive the formation of positively valenced, task-relevant relationships in teams.

Similarity-attraction is a mechanism of relational bonding based on ingroup favoritism; individuals exhibit preferences for similar others while failing to prefer dissimilar others. This tendency—of individuals to favor ingroups over outgroups—is a form of discrimination, and research has indicated that people readily establish these patterns of discriminatory behavior. For instance, ingroup favoritism even occurs when only minimal, arbitrary information is provided as a means for distinguishing groups (Blanz et al., 1995; Mummendy et al., 2000; Tajfel, 1982; Tajfel et al., 1971). When exaggerated, ingroup favoritism can lead to outgroup derogation, or the aggressive denigration of dissimilar individuals (Brewer, 1979; Hewstone et al., 2002). Some scholars have even suggested that similarity-attraction effects are nothing more than misinterpreted signs of outgroup derogation (Rosenbaum, 1986; Rosenbaum & Holtz, 1985). Although the dissimilarity-repulsion phenomenon is not studied well than similarity-attraction, the scholarly literature indicated that based on certain, specific characteristics, dissimilarity does indeed reduce interpersonal attraction between people (e.g., Singh & Tan, 1992).

Analogous to the finding that attitude similarity leads to attraction, research has also indicated that attitude dissimilarity leads to interpersonal repulsion (Rosenbaum, 1986). In fact, dissimilarity-repulsion may even be a more powerful interpersonal force than similarity-attraction; research has indicated a positive-negative asymmetry effect occurs with attitude similarity and dissimilarity, meaning that the former has a positive effect which is weaker in magnitude than the latter’s negative effect (Singh et al., 2008a,b). For example, attitude dissimilarity has a disproportionately strong negative impact on interpersonal liking and enjoyment of the company, when contrasted with the positive effect of attitude similarity (Singh & Ho, 2000). Furthermore, not only do people tend to be repulsed by those who champion alternative attitudes, but they also experience the most extreme repulsion when these comparison others are ingroup members. For instance, when individuals share a political affiliation or sexual orientation, research has shown that they assume they are similar in other ways, and consequently are more repulsed when their dissimilar attitudes are elucidated than they would have been if they had initially assumed dissimilarity (Chen & Kenrick, 2002).

In general, there is clear evidence to suggest that deep-level heterophily repels individuals from one another and that these results hold true for different types of heterophily and different types of relational ties. Accordingly, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 2b: Deep-level diversity will drive the formation of negatively valenced, task-relevant relationships in teams.

The diversity of deep-level attributes has also been studied in relation to team performance and other performance-relevant outcomes. In general, meta-analytic research has indicated mixed findings when reporting on the relation between deep-level diversity and team performance; some research has indicated no relation between either deep-level diversity and performance or cohesion (Webber & Donahue, 2001), while other research has suggested a positive relation between deep-level diversity and performance (Horowitz & Horowitz, 2007). Overall, the effects of deep-level diversity characteristics on team outcomes have been shown to strengthen over time, as group members become better acquainted with one another (Harrison et al., 1998, 2002). Attitudinal diversity is one type of deep-level variance that has been used to predict team performance; attitudinally diverse teams produce more creative output than attitudinally homogeneous teams (Triandis et al., 1965). Attitudinal diversity is also related to other team-level performance-relevant outcomes. For instance, team attitude heterogeneity negatively predicts team cohesiveness (Good & Nelson, 1973). Specifically, job satisfaction diversity negatively predicts group cohesion and that relation strengthens over time (Harrison et al., 1998). In addition, team diversity in terms of outcome importance—or, the value of doing the team’s work well—negatively predicts team social integration, and both diversity in terms of outcome importance and task meaningfulness—or, personal salience of the team’s work—negatively predict collaboration (Harrison et al., 2002).

Accordingly, based on the aforementioned literature, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 3: Teams that are diverse at the deep-level will outperform teams that are homogeneous at the deep-level.

Data were collected from a sample of 417 students who self-assembled into 139 three-person teams to complete a decision-making task.

Participants for this study were recruited from the psychology research participation pool at a large university in Southern California. Participants’ average age was 18.86 years (SD = 1.55 years). In terms of gender, 76.98% identified as female, 19.66% identified as male, and 3.36% identified as other/no response. In terms of race/ethnicity, 43.64% identified themselves as Hispanic/Latino, 24.70% as Asian, 16.55% as White, 11.99% as other/mixed race/no response, 1.68% as Black/African American, and 1.44% as Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander.

After completing an electronic consent form and survey, participants signed up for the laboratory study. During laboratory sessions, participants were given name tags with aliases (Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, and Purple), and were told to refer to one another by said aliases.

During the laboratory session, participants worked in self-assembled, three-person teams. Specifically, participants were invited into the research laboratory in groups of six. Initial seating assignments were randomized. After an initial briefing, participants were instructed to form into teams of three. They were not given any instructions on how to form into teams and were not given a time limit. Once teams were formed, they were sent to breakout rooms to complete the decision-making activity. In other words, the current methodology allowed participants to independently form into small groups and then analyze the emergent relationships and outcomes of the self-assembled small groups. This methodology was strategically employed in an attempt to maximize the psychological meaningfulness of fledgling connections between participants; prior research has indicated that self-assembling into a team is a form of interpersonal attraction, and thus self-assembled teammate relationships have clearer implications for emergent relational phenomena such as homophily than other common methods of forming teams in the lab, such as random assignment (e.g., Wax et al., 2017).

These teams were ad hoc, meaning that they formed on-the-spot, in the research lab. The decision to focus on ad hoc teams was also intentional, as ad hoc teams are increasingly common in modern-day workplaces, a trend that has been reflected in the scholarly literature (e.g., Roberts et al., 2014; Sjögren et al., 2018).

Teams worked to complete a hidden profile decision-making task (e.g., Brodbeck et al., 2002; Stasser & Titus, 1985). Specifically, the hidden profile procedure involved having participants (1) individually read over sheets of information on three potential job applicants, (2) discuss the applicants as a team, and (3) decide whom to hire as a team. Unbeknownst to the participants, the information on the applicants was asymmetrically distributed, meaning that some information on each application was shared across all three participants, and some information was unique to a single participant. The objectively correct hiring decision would only become clear if the unique information was shared during group discussion.

After finishing the decision-making task, participants completed electronic questionnaires via Qualtrics (2018), using iPads. The duration of the laboratory portion of the study was 1 hr and 30 min or less.

The following survey-based measures were electronically administered to all participants using Qualtrics survey software (2018). Participants completed demographic items at home, prior to their laboratory sessions. Social- and task-relevant ties were assessed at the very end of the laboratory session before participants were dismissed.

Social ties were assessed in two ways. First, liking was gauged via the following item: “Who did you like working with?” Second, trust was gauged via the following item: “Who do you trust?” For both items, participants were presented with the aliases of their two teammates as response options.

Task-relevant ties were also assessed in two ways. First, transactive memory systems (TMSs) were mapped via the following item: “Who do you believe has specialized knowledge relevant to the task?” Second, hindrance was gauged via the following item: “Who made it difficult for you to carry out your job responsibilities?” For both items, participants were presented with the aliases of their two teammates as response options.

Participants were asked to report the following demographic variables: gender, age, race/ethnicity, political preference, and sexual orientation. Gender was assessed by asking: “What is your gender?” Response options included “Male,” “Female,” and “Other.” Race/ethnicity was self-reported using the following question: “What is your race/ethnicity? Check all that apply.” Response options included “American Indian or Alaska Native,” “Asian,” “Black or African American,” “Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander,” “White,” “Hispanic or Latino,” and “Other.” Age was evaluated via the following item: “What is your age?” Participants responded to this item via a dropdown list of numbers.

To test hypotheses related to deep-level demographics, sexual orientation and political preference were evaluated. Sexual orientation was evaluated using the following item: “What is your sexual orientation?” Response options included “Heterosexual,” “Homosexual,” “Bisexual,” and “Other.” Political preference was assessed using the following item: “What political party do you primarily identify with?” Response options included “Democratic,” “Republican,” and “Other.”

Team performance was measured based on the decision of the team during a hidden profile task. During this portion of the study, participants first had to individually memorize a list of information on three fictitious job candidates (Anderson, Barnes, and Carter). Next, they came together to discuss the memorized information, and finally, they made a team-level decision on whom to hire (which they verbally reported to a research assistant, who then recorded the team’s response). Based on the shared/unique distribution of positive, negative, and neutral information, Anderson is the objectively correct response, indicative of unbiased information sharing. While Barnes and Carter are both considered incorrect responses, Barnes reflects a more extreme information-sharing bias than Carter.

Exponential random graph models (ERGMs) were used to test Hypotheses 1 and 2. ERGMs are used to predict/explain why relationships form between individuals. In ERGM, the observed relationships between individuals in the sample are considered just one potential patterning of how that number of people could potentially form relationships with one another; in other words, relationships are regarded as random variables. Parameter estimates reflect hypotheses regarding the reasons why the relationships formed in the specific way that they did. ERGM is mathematically similar to logistic regression, except for the fact that relationships (i.e., the outcome variable) are assumed to be dependent on one another in ERGM, whereas logistic regression assumes that observations are independent (Robins et al., 2007).

In order to answer both Hypotheses 1 and 2, we ran four ERGMs using identical parameter estimates and the following observed networks: liking, trust, hindrance, and TMS. We controlled for edges (i.e., number of relationships), and sender and receiver effects for all variables in all analyses. Also, because of the relationship between gender and sexual orientation, the main effect and homophily parameter estimates for gender were included as covariates in all models.

We imposed a block-diagonal constraint on all of the ERGMs that we conducted. This constraint communicates to the model that “edges are only allowed within subsets of the node set” (Krivitsky et al., 2021). Accordingly, for the current study, this approach ensured that between-team zeros were structural zeros, with only within-team edges being analyzed. Furthermore, we measured research participants’ prior familiarity with one another and considered using this as a covariate in our analyses. However, the prior familiarity network was notably sparse, likely due to the fact that the sample was collected at a large commuter college where students do not interact with one another to a substantial degree. Therefore, this parameter was excluded from the final analyses to maximize the model fit.

Before testing Hypothesis 3, Blau indices (1977) were calculated at the team level for sexual orientation, political preference, and gender (as a covariate). Subsequently, multinomial logistic regression was used to test Hypothesis 3. This type of regression, an extension of binary logistic regression, allows for categorical dependent variables with 3+ categories. Team performance was entered as the outcome variable, and the Blau indices for sexual orientation, political preference, and gender were entered as the predictor variables.

ERGM revealing the impact of deep-level homophily on social tie formation.

| Parameter | Liking | Trust | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect estimate | SE | Odds ratio | Effect estimate | SE | Odds ratio | |

| Covariates | ||||||

| edges | 2.45* | 0.71 | — | 1.60* | 0.48 | — |

| nodeifactor | ||||||

| Nonheterosexual | −0.64 | 0.50 | 0.53 | −0.07 | 0.37 | 0.93 |

| Republican | 0.31 | 0.47 | 1.36 | −0.29 | 0.28 | 0.75 |

| Other political preference | −0.14 | 0.38 | 0.87 | −0.24 | 0.26 | 0.79 |

| Female | −0.10 | 0.39 | 0.90 | −0.09 | 0.26 | 0.91 |

| Other gender | 1.08 | 0.86 | 2.94 | 0.39 | 0.61 | 1.48 |

| nodeofactor | ||||||

| Nonheterosexual | 0.76 | 0.60 | 2.14 | 0.28 | 0.38 | 1.32 |

| Republican | 0.28 | 0.45 | 1.32 | 0.19 | 0.30 | 1.21 |

| Other political preference | 0.13 | 0.39 | 1.14 | −0.05 | 0.26 | 0.95 |

| Female | −0.29 | 0.40 | 0.75 | −0.19 | 0.26 | 0.83 |

| Other gender | −1.47 | 0.84 | 0.23 | −0.38 | 0.60 | 0.68 |

| nodematch | ||||||

| Gender | 0.07 | 0.39 | 1.07 | 0.08 | 0.25 | 1.08 |

| Deep-level homophily (nodematch) | ||||||

| Sexual orientation | −0.06 | 0.48 | 0.94 | −0.14 | 0.35 | 0.87 |

| Political preference | 0.24 | 0.36 | 1.27 | −0.12 | 0.23 | 0.89 |

t = number of teams = 139. n = number of individuals = 417. l = number of teammate relationships = 834. edges = parameter that accounts for the number of relationships in the network expected to occur by chance. nodeifactor/nodeofactor = parameters that indicate the number of times that a node with a given attribute appears in an edge in the network; used to control for the main effects of categorical variables. nodematch = parameter that counts of the number of edges (i, j) for which attribute (i) = attribute (j); used to test for homogeneity for categorical variables. Gender was coded as 1 = male, 2 = female, 3 = other. Sexual orientation was coded as 1 = heterosexual, 2 = nonheterosexual (homosexual, bisexual, other, and no response). Political preference was coded as 1 = Democratic, 2 = Republican, and 3 = other/no response.

p < 0.001.

ERGM, exponential random graph model; SE, standard error.

In terms of sexual orientation, 86.33% of the sample was identified as heterosexual, 2.88% identified as homosexual, 5.51% identified as bisexual, 1.44% identified as other, and 3.84% gave no response. For political preference, 68.82% were identified as Democratic, 11.51% identified as Republican, 13.91% identified as other, and 5.76% gave no response.

ERGM revealing the impact of deep-level homophily on task-relevant tie formation.

| Parameter | TMS | Hindrance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect estimate | SE | Odds ratio | Effect estimate | SE | Odds ratio | |

| Covariates | ||||||

| edges | −5.98*** | 0.27 | — | −10.05*** | 0.85 | — |

| nodeifactor | ||||||

| Nonheterosexual | 0.06 | 0.21 | 1.06 | 0.72 | 0.47 | 2.05 |

| Republican | 0.16 | 0.18 | 1.17 | 0.12 | 0.44 | 1.13 |

| Other political preference | 0.18 | 0.15 | 1.20 | 0.17 | 0.36 | 1.19 |

| Female | −0.02 | 0.15 | 0.98 | 0.66 | 0.54 | 1.93 |

| Other gender | −0.43 | 0.34 | 0.65 | −0.44 | 0.98 | 0.64 |

| nodeofactor | ||||||

| Nonheterosexual | −0.44 | 0.22 | 0.64 | −0.52 | 0.55 | 0.59 |

| Republican | −0.33 | 0.18 | 0.72 | −0.55 | 0.54 | 0.58 |

| Other political preference | 0.09 | 0.15 | 1.09 | 0.55 | 0.34 | 1.73 |

| Female | 0.02 | 0.15 | 1.02 | 1.14* | 0.56 | 3.13 |

| Other gender | 0.45 | 0.35 | 1.57 | 1.86* | 0.85 | 6.42 |

| nodematch | ||||||

| Gender | 0.41** | 0.14 | 1.51 | −0.28 | 0.52 | 0.76 |

| Deep-level homophily (nodematch) | ||||||

| Sexual orientation | −0.41* | 0.20 | 0.66 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 1.73 |

| Political preference | 0.12 | 0.14 | 1.13 | 0.69* | 0.31 | 1.99 |

t = number of teams = 139. n = number of individuals = 417. l = number of teammate relationships = 834. edges = parameter that accounts for the number of relationships in the network expected to occur by chance. nodeifactor/nodeofactor = parameters that indicate the number of times that a node with a given attribute appears in an edge in the network; used to control for the main effects of categorical variables. nodematch = parameter that counts of the number of edges (i, j) for which attribute (i) = attribute (j); used to test for homogeneity for categorical variables. Gender was coded as 1 = male, 2 = female, 3 = other. Sexual orientation was coded as 1 = heterosexual, 2 = nonheterosexual (homosexual, bisexual, other, and no response). Political preference was coded as 1 = Democratic, 2 = Republican, and 3 = other/no response.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

ERGM, exponential random graph model; SE, standard error; TMS, transactive memory system.

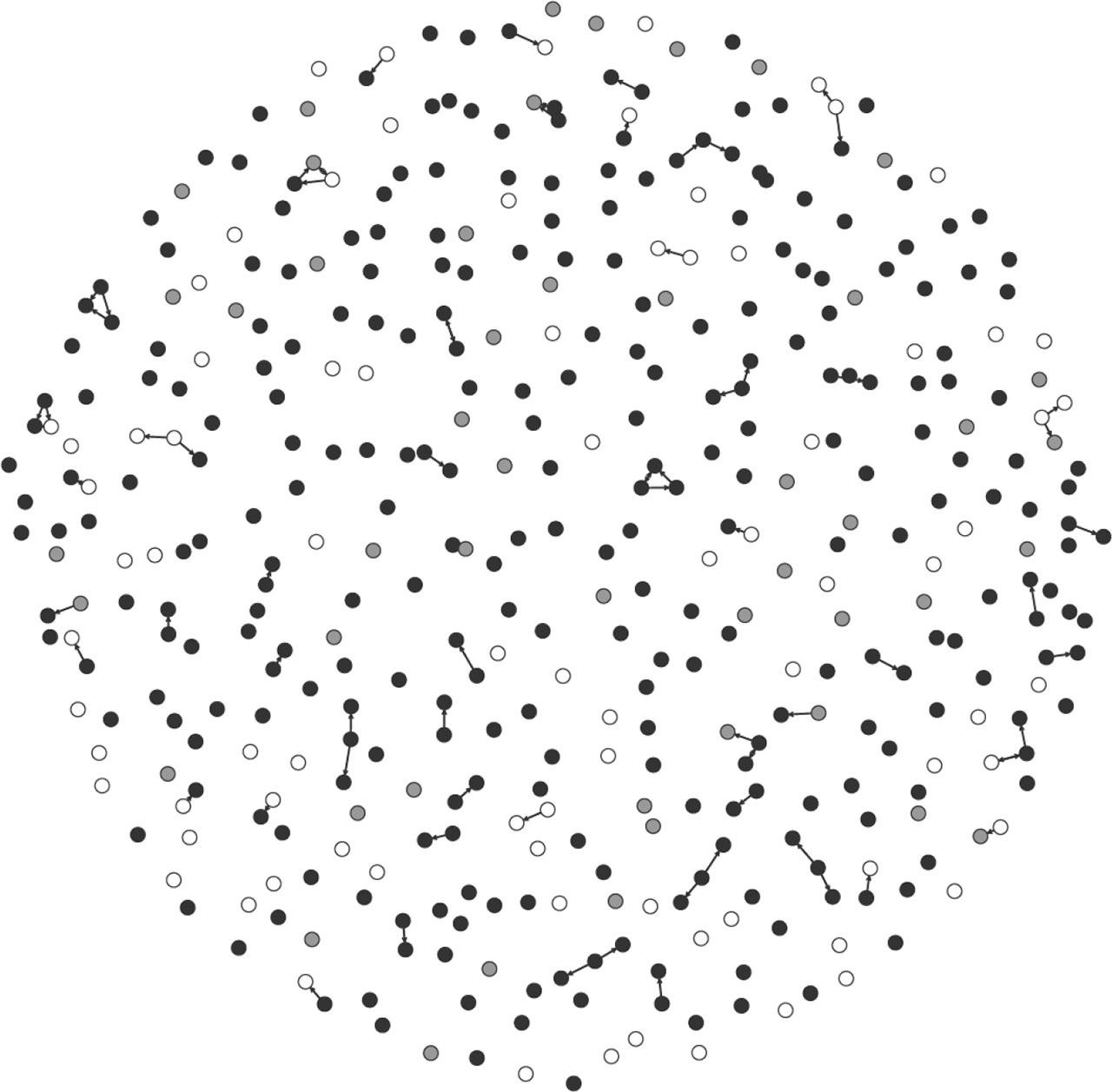

Sociogram depicting hindrance relationships, with node shade indicating political preference. (n = number of individuals = 417; black = democratic; gray = republican; white = other/no response).

Binary logistic regression predicting performance for lowest- and highest-performing teams (t = 113).

| Parameter | Beta | SE | Odds ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender diversity (covariate) | −1.34 | 1.21 | 0.26 |

| Sexual orientation diversity | −0.08 | 1.22 | 0.92 |

| Political preference diversity | 2.25* | 1.23 | 9.52 |

t = number of teams = 139. Coding for performance DV: highest performance = 1, lowest performance = 0. Diversity for all variables operationalized as Blau indices.

p = 0.07.

SE, standard error.

To answer Hypothesis 1—which posited that deep-level similarity would drive the formation of social ties in teams—we utilized the nodematch ERGM parameter to estimate the sexual orientation and political preference homogeneity for both the liking and the trust outcome networks. Neither model indicated any significant results for either sexual orientation homophily or political preference homophily. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was not supported.

To answer Hypothesis 2—which posited that (a) deep-level similarity would drive the formation of positively valenced, task-relevant relationships in teams and (b) deep-level diversity would drive the formation of negatively valenced, task-relevant relationships in teams—we again utilized the nodematch ERGM parameter to estimate sexual orientation and political preference homogeneity, this time for the TMS and hindrance outcome networks. Results for the TMS network, on the other hand, indicated a significant effect of sexual orientation heterophily (estimate = −0.41, p < 0.05), but no significant effect of political preference homophily. Results for the hindrance network indicated a significant effect of political preference homophily (estimate = 0.69, p < 0.05)(1), but no significant effect of sexual orientation homophily. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was not supported.

In terms of team performance, 12.20% of teams in the sample chose Anderson (indicative of unbiased information sharing), while 69.10% chose Barnes (indicative of highly biased information sharing) and 18.70% chose Carter (indicative of moderately biased information sharing). In order to test Hypothesis 3—which posited that deep-level-diverse teams would outperform deep-level-homogenous teams—we ran a binary logistic regression comparing the highest- and lowest-performing teams, using Blau indices for team gender, sexual orientation, and political preference as predictors of team decision-making performance. Results indicated that political preference diversity predicts performance, but only at a marginally significant level (b = 2.25, p = 0.07). Specifically, this result implies that more politically diverse teams were more likely to choose Anderson (the correct response) than to choose Barnes (an incorrect response). All other results were nonsignificant.

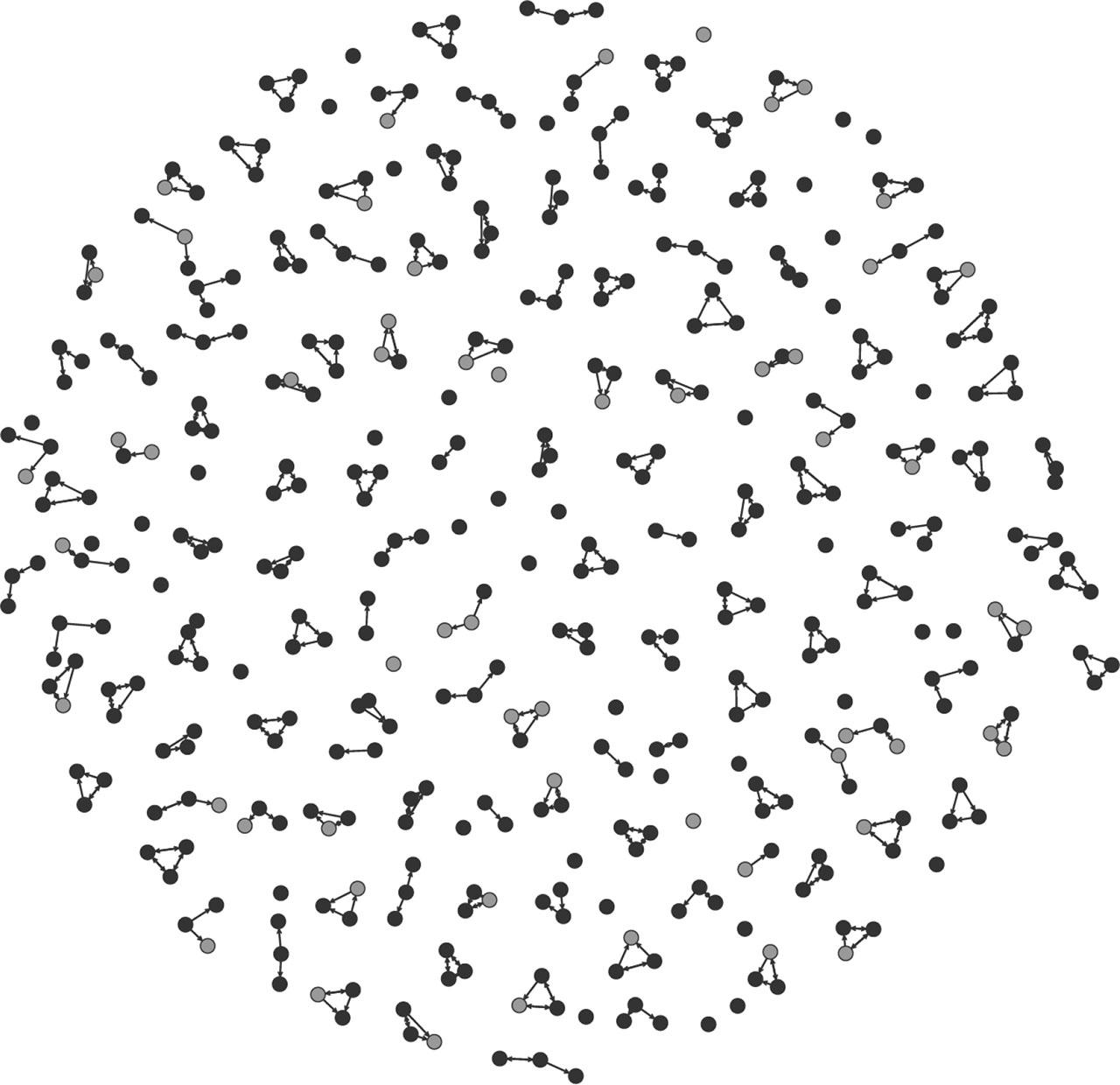

Sociogram depicting TMS relationships, with node shade indicating sexual orientation. (n = number of individuals = 417; black = heterosexual; gray = nonheterosexual). TMS, transactive memory system.

The old adage, “birds of a feather flock together,” has traditionally been supported by empirical research; by and large, studies have confirmed that similar others tend to prefer one another (Ertug et al., 2022; McPherson et al., 2001). However, it is yet unclear whether this finding holds true when considering a variety of deep-level diversity variables, or the type of relational outcome. Accordingly, the current study explored the impact that deep-level homophily has on the creation of social and task-relevant relationships between teammates.

Hypothesis 1 posited that deep-level similarity would drive the formation of social ties in teams. ERGM results failed to support this hypothesis and there was no significant effect of either sexual orientation or political preference homophily on either liking or trust relationships. Although this finding is nonsignificant—and therefore should not be subject to further interpretation—it is interesting to note that individuals did not exhibit the typical homophilous patterning of relationships, suggesting that people are not always driven toward homophily.

It is possible that Hypothesis 1 was not supported due to the methodological choice in demographic categories (e.g., sexual orientation and political preference) meant to reflect deep-level characteristics. In line with this notion, previous research has shown that, when comparing heterosexual and nonheterosexual individuals, differences in gender-based friendship homophily tend to be minimal. (Gillespie, et al., 2015). Similarly, past research has demonstrated that the prevalence of politically homophilous relationships varies based on a variety of dimensions. For instance: (1) political homophily is prevalent in romantic relationships (Huber & Malhotra, 2017), perhaps more so than in nonromantic relationships; (2) political homophily is more prevalent for people with extreme political views than for those with moderate political views (Bond & Sweitzer, 2022); and, (3) political homophily is less prevalent online during periods of increased political engagement than during periods of decreased political engagement (Boutyline & Willer, 2017). Accordingly, these social demographics may not be the best exemplars of characteristics that drive deep-level homophily, overall.

Hypothesis 2a posited that deep-level similarity would drive the formation of positively valenced, task-relevant relationships in teams. Again, this hypothesis was not supported; however, results did indicate a significant effect of sexual orientation diversity on the formation of TMS ties between individuals. Although this finding defies the logic of similarity-attraction, it makes sense when considering the importance of informational diversity in teams. Teams that are composed of members with diverse informational resources have been shown to outperform teams with more homophilous informational resources (e.g., Bernstein, 2016; Jehn et al., 1999). Moreover, it is important to note that the relational outcome—TMS ties—directly reflects whether individuals found their teammates as valuable sources of unique information (or not). Based on these results, it follows that sexual orientation diversity may be an important proxy for informational diversity.

Furthermore, results from Hypothesis 2a provide some support for the theory of need complementarity, which states that people are attracted to individuals with characteristics that complement their own, rather than being drawn to people with similar characteristics (Winch et al., 1954). Previously, this theory has received scattered support, at best; for instance, research has indicated that the theory is only applicable to long-term relationships (Kerckhoff & Davis, 1962) and certain characteristics that are inherently complementary such as nurturance and dependence (Rychlak, 1965). In addition, people tend to self-report wanting a romantic partner with a complementary personality; for example, women tend to report wanting a more conscientious, more extroverted, and less neurotic partner (Dijkstra & Barelds, 2008). However, need complementarity is not generally believed to be a major driver of relational attraction (Bowerman & Day, 1956; Epstein & Guttman, 1984; Klohnen & Mendelsohn, 1998; Luo & Klohnen, 2005).

Although need complementarity has all but been revoked by the mainstream attraction literature, there have been some indications that the theoretical lens may be better suited to studying attraction in teams (Bell & Mascaro, 1972; Haythorn, 1968). For instance, research has indicated that people purposely seek out teammates with complementary skills to their own (Zhu et al., 2013). Additionally, people report being more attracted to their teams when they are high on complementary fit with regards to personality characteristics such as extraversion (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005). The results from the test of Hypothesis 2a add support to the theory of need complementarity as it relates to the teamwork context.

Hypothesis 2b posited that deep-level diversity would drive the formation of negatively valenced, task-relevant relationships in teams. Again, this hypothesis was not supported; however, results did indicate a significant effect of political preference homophily on the formation of hindrance ties between individuals. In other words, the current study’s results directly contradict Rosenbaum’s (1986) repulsion hypothesis. One reason for this may be that the current sample was a particularly open-minded one; evidence from past research has shown that the effect of dissimilarity-repulsion is the strongest in samples of highly prejudiced people, and weaker in samples of less prejudiced people (Pilkington & Lydon, 1997). Being that the current sample was a highly diverse group of young adults attending a socially progressive school, it is plausible that this sample had less of a proclivity to feel repulsed by dissimilar others than previous samples had. Another potential reason for this unusual patterning of results may be that politically similar individuals had a higher likelihood of conversing with one another than politically disparate individuals did. If this is the case, then it is possible that politically disparate individuals were less likely to develop conflict-laden relationships, simply because they were less likely to develop relationships at all than were politically similar dyads. A third explanation for this finding may be that conservative students are skilled at ingratiating themselves with progressive students. The current sample was taken from a socially and politically progressive population of students; conservative students in this population may work to pass as progressive, to avoid conflict and get along amicably with their peers.

Hypothesis 3 posited that those who are diverse at the deep-level would outperform teams that are homogeneous at the deep-level. This hypothesis was partially supported, but only at a level of marginal significance; specifically, politically diverse teams were more likely to choose a correct response than an incorrect response. Restated, these results imply that deep-level diversity happens organically sometimes, and when it does happen, team performance tends to trend in the positive direction, although not significantly. This finding is in line with past research on deep-level diversity, which has shown that it is good for team performance (e.g., Bell, 2007; Bell et al., 2011), regardless of whether team members are aware of said diversity or not.

The current study is not without its limitations. First, the findings may not be widely generalizable. The current sample was mostly Democratic, and embedded within a socially progressive academic institution. Thus, it is possible that the progressive nature of the sample led to certain results—such as the finding that deep-level diversity predicts positively valenced, task-relevant relationships in teams—thereby limiting the generalizability of said findings. Second, the design of this study was descriptive in nature, limiting our ability to draw causal conclusions, and limiting the internal validity of the study. Third, with regards to Hypotheses 1 and 2, it is clear from past research that deep-level characteristics matter, but not from the onset of teamwork (e.g., Harrison et al., 2002). Thus, it is unlikely that individuals in this study were consciously aware of one another’s deep-level characteristics; yet, deep-level characteristics were shown to have a significant effect on the formation of relationships. Accordingly, it is possible that these findings are attributable to the third variable problem, and that the true origin of this patterning of results went unmeasured in the current study. Finally, the results of the logistic regression were either nonsignificant or only marginally significant. This pattern of results (or lack thereof) implies that team performance may be better accounted for by other variables, apart from team diversity.

Future research should investigate whether perceptions of deep-level diversity moderate the relation between objective diversity and team outcomes. In other words, scholars should investigate whether it is necessary or not for team members to be aware of one another’s deep-level characteristics for deep-level homophily/heterophily to drive the formation of relationships on teams, or whether heightened awareness of attributes of teammates magnifies the impact that deep-level diversity has on group processes and emergent relationships.

In addition, the results of this study suggested that homophily is not a universal truth; there are certain contexts where individuals do not revert to homophily as a default. Thus, future research should investigate a variety of contexts, to determine when homophily is common and when it is rare. Finally, future research should investigate whether valuing diversity moderates the relation between homophily and teammate relationships.

The current study reexamined the finding that homophily predicts human relationships, by examining the relation between deep-level diversity and (a) social relationships, (b) task-relevant relationships, and (c) team performance. The results indicated that (1) deep-level diversity drives positive, task-relevant relationships, (2) deep-level homophily drives negative, task-relevant relationships, and (3) deep-level diversity predicts team task performance, but only to a marginal extent. The current results suggest that a variety of contextual factors should be considered to gauge whether homophily is likely or not.

Due to the negative valence of hindrance ties, this result is indicative of homophily driving interpersonal repulsion.